James B. McCreary

Encyclopedia

James Bennett McCreary was a lawyer and politician from the US state of Kentucky

. He represented the state in both houses of the U.S. Congress

and served as its 27th and 37th governor

. Shortly after graduating from law school, he was commissioned as the only major

in the 11th Kentucky Cavalry, serving under Confederate

Brigadier General John Hunt Morgan

during the American Civil War

. He returned to his legal practice after the war. In 1869, he was elected to the Kentucky House of Representatives

where he served until 1875; he was twice chosen Speaker of the House. At their 1875 nominating convention, state Democrats

chose McCreary as their nominee for governor, and he won an easy victory over Republican

John Marshall Harlan

. With the state still feeling the effects of the Panic of 1873

, most of McCreary's actions as governor were aimed at easing the plight of the state's poor farmers.

In 1884, McCreary was elected to the first of six consecutive terms in the U.S. House of Representatives

. As a legislator, he was an advocate of free silver

and a champion of the state's agricultural interests. After two failed bids for election to the Senate

, McCreary secured the support of Governor J. C. W. Beckham

, and in 1902, the General Assembly elected him to the Senate. He served one largely undistinguished term, and Beckham successfully challenged him for his Senate seat in 1908. The divide between McCreary and Beckham was short-lived, however, and Beckham supported McCreary's election to a second term as governor in 1911.

Campaigning on a platform of progressive

reforms, McCreary defeated Republican Edward C. O'Rear in the general election. During this second term, he became the first inhabitant of the state's second (and current) governor's mansion

; he is also the only governor to have inhabited both the old

and new mansions. During his second term, he succeeded in convincing the legislature to make women eligible to vote in school board elections, to mandate direct primary election

s, to create a state public utilities commission

, and to allow the state's counties to hold local option

elections to decide whether or not to adopt prohibition

. He also realized substantial increases in education spending and won passage of reforms such as a mandatory school attendance law, but was unable to secure passage of laws restricting lobbying in the legislative chambers and providing for a workers' compensation

program. McCreary was one of five commissioners charged with overseeing construction of the new governor's mansion and exerted considerable influence on the construction plans. His term expired in 1916, and he died two years later. McCreary County

was formed during McCreary's second term in office and was named in his honor.

, on July 8, 1838. He was the son of Edmund R. and Sabrina (Bennett) McCreary. He obtained his early education in the region's common schools, then matriculated to Centre College

in Danville, Kentucky

, where he earned a bachelor's degree in 1857. Immediately thereafter, he enrolled at Cumberland University

in Lebanon, Tennessee

, to study law. In 1859, he earned a Bachelor of Laws

from Cumberland and was valedictorian

of his class of forty-seven students; he was admitted to the bar

and commenced practice at Richmond.

Shortly after the Battle of Richmond on August 29, 1862, David Waller Chenault, a Confederate sympathizer from Madison County

, came to Richmond to raise a Confederate regiment. On September 10, 1862, Chenault was commissioned as a colonel

and given command of the regiment, dubbed the 11th Kentucky Cavalry. McCreary joined the regiment and was commissioned as a major

, the only one in the unit. The 11th Kentucky Cavalry was pressed into immediate service, conducting reconnaissance

and fighting bushwhacker

s. Just three months after its muster, they helped the Confederate Army

secure a victory at the Battle of Hartsville

. In 1863, the unit joined John Hunt Morgan

for his raid into Ohio

. Colonel Chenault was killed as the Confederates tried to capture the Green River

Bridge at the July 4, 1863, Battle of Tebbs Bend

. McCreary assumed command of the unit after Chenault's death. Following the battle, he was promoted to the rank of lieutenant colonel on the recommendation of John C. Breckinridge

.

Most of the 11th Kentucky Cavalry was captured by Union forces

at the Battle of Buffington Island

on July 17, 1863. Approximately two hundred men, commanded by McCreary, mounted a charge and escaped their captors, but they were surrounded the next day and surrendered. McCreary was taken to Ninth Street Prison in Cincinnati, Ohio, but was later transferred to Fort Delaware

and eventually to Morris Island

, South Carolina

, where he remained a prisoner through July and most of August 1863. In late August, he was released as part of a prisoner exchange

and taken to Richmond, Virginia

. He was granted a thirty-day furlough

before being put in command of a battalion

of Kentucky and South Carolina troops. He commanded this unit, primarily on scouting missions, until the end of the war.

Following the war, McCreary resumed his legal practice. On June 12, 1867, McCreary married Katherine Hughes, the only daughter of a wealthy Fayette County

farmer. The couple had one son.

for the ticket of Democrat Horatio Seymour

in 1868; though he declined to serve, he attended the national convention

as a delegate. His political career began in earnest in 1869 when he was elected to the Kentucky House of Representatives

.

In 1871, McCreary was re-elected to the state House without opposition. In the upcoming legislative session, the major question was expected to be the Cincinnati Southern Railway

's request for authorization to build a track connecting Cincinnati, Ohio, with either Knoxville

or Chattanooga, Tennessee

, through Central Kentucky

. The action was opposed by the Louisville and Nashville Railroad

, a bitter rival of the Cincinnati line. Appeals to the General Assembly

to oppose the bill on grounds that an out-of-state corporation should not be granted a charter in the state were successful in 1869 and 1870, and an attempt by the federal Congress to grant the charter was defeated by states' rights

legislators there. Moreover, newly elected governor Preston Leslie

had opposed a bill granting Cincinnati Southern's request when he was in the state Senate

in 1869. In the lead-up to the 1871 session, frustrated Central Kentuckians threatened to defect from the Democratic Party in future elections if the bill were not passed in the session. Supporters of Cincinnati Southern won a victory when McCreary, a staunch supporter of the bill to grant the line's request, was elected Speaker of the House. After approval of a series of amendments designed to give Kentucky courts some jurisdiction in cases involving the line and the Kentucky General Assembly some measure of control over the line's activities, the bill passed the House by a vote of 59–38. The vote in the Senate resulted in a 19–19 tie; President Pro Tem

John G. Carlisle—a native of Covington

, through which the proposed line would pass—cast the deciding vote in favor of approving Cincinnati Southern's request. With the will of the people clearly expressed through the legislature, Governor Leslie did not employ his gubernatorial veto. McCreary was again returned to the House without opposition in 1873 and was again chosen Speaker of the House during his term.

, J. Stoddard Johnson, and George B. Hodge. Williams was considered the favorite for the nomination at the outset of the Democratic nominating convention, despite attacks on his character by newspapers in the western part of the state. However, McCreary defeated Williams on the fourth ballot.

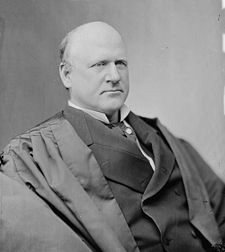

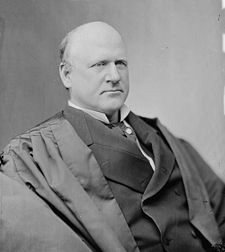

The Republicans nominated John Marshall Harlan

The Republicans nominated John Marshall Harlan

, who had served in the Union Army. In joint debates across the state, McCreary stressed what many Kentuckians felt were abuses of power by Republican President Ulysses S. Grant

during the Reconstruction Era. Harlan countered by faulting the state's Democratic politicians for continuing to dwell on war issues almost a decade after the war's end. He also attacked what he perceived as Democratic financial extravagance and the high number of pardons granted by sitting Democratic governor Preston Leslie. Harlan claimed these as evidence of widespread corruption in the Democratic Party. McCreary received solid support from the state's newspapers, nearly all of which had Democratic sympathies. Despite a late infusion of cash and stump speakers in favor of his opponent, McCreary won the general election by a vote of 130,026 to 94,236.

At the time of McCreary's election, his wife Kate was the youngest first lady in the Commonwealth's history. Due to the near completion of an annex to the state capitol building by the time of McCreary's inauguration, he was able to move the official governor's office out of the governor's mansion

, freeing his family from the intrusion of public business into their private quarters. McCreary's receipt of the executive journal and Great Seal of the Commonwealth from outgoing Governor Leslie in the mansion's office is believed to be the last official act performed by a governor there.

In the wake of the Panic of 1873

, the electorate was primarily concerned with economic issues. In his first address to the General Assembly, McCreary focused on economic issues to the near exclusion of providing any leadership or direction in the area of government reforms. (In later years, McCreary's unwillingness to take a definite stand on key issues of reform would earn him the nicknames "Bothsides" McCreary and "Oily Jeems".) In response to McCreary's address, legislators from the rural, agrarian areas of the state proposed lowering the maximum legal interest rate from ten percent to six percent. The proposed legislation drew the ire of bankers and capitalists; it was also widely panned in the press, notably by Louisville Courier-Journal editor Henry Watterson

. Ultimately, the Assembly compromised on a legal interest rate of eight percent. Another bill to lower the property tax

rate from 45 to 40 cents per 100 dollars of taxable property encountered far less resistance and passed easily. Few bills passed during the session had statewide impact, despite McCreary's insistence that the legislature prefer general bills over bills of local impact. This fact, too, was widely criticized by the state's newspapers.

The issue of improving navigation along the Kentucky River

was raised numerous times by Representative James Blue during the 1876 legislative session. Despite Blue's promises of manifold benefits to the state from such an investment, parsimonious legislators defeated a bill allocating funds for the improvements. The issue gained traction with some voters during the biennial legislative elections, however, which brought it back to the floor in the 1878 session. Prompted by recommendations from the Kentucky River Navigation Convention in 1877, McCreary abandoned his typical fiscal conservatism and joined the calls for improvements along the river. In response, legislators passed a largely ineffective bill providing that, if funds could be raised through special taxes in districts along the river, the state would provide the funds to maintain the improvements.

Also in the 1878 session, tax assessments for railroad property were raised to match those of other property. Agrarian interests were pleased that the legal interest rate was again lowered, now reaching the six percent they had proposed in the previous session. Non-economic reforms included the separation of Kentucky Agricultural and Mechanical College (later the University of Kentucky

) from Kentucky University (later Transylvania University

) and the establishment of a state board of health. Bills of local import again dominated the session, representing 90 percent of the acts and resolutions passed by the Assembly.

Along with Democrats John Stuart Williams, William Lindsay, and J. Proctor Knott

, and Republican Robert Boyd, McCreary was nominated for a U.S. Senate

seat in 1878. Democrats were divided by sectionalism and initially unable to unite behind one of their four candidates. After more than a week of caucus

ing among Democratic legislators, the nominations of McCreary, Knott, and Lindsay were withdrawn, and Williams was elected over Boyd. Historian Hambleton Tapp opined that the withdrawals were likely a part of some kind of deal among legislators, although the details of the deal, if it ever existed, were not made public.

. His opponents for the Democratic nomination were Milton J. Durham

and Philip B. Thompson, Jr.

, both of whom had held the district's seat previously. McCreary bested both men, and in the general election in November, defeated Republican James Sebastian by a margin of 2,146 votes. It was the largest margin of victory by a Democrat in the Eighth District.

During his tenure, McCreary represented Kentucky's agricultural interests, introducing a bill to create the United States Department of Agriculture

. A bill containing most of the same provisions as the one McCreary authored was passed later in the session. He also proposed a successful amendment to the Wilson–Gorman Tariff Act that excluded farm implements and machinery from the tariff. An advocate of free silver

, he was appointed by President Benjamin Harrison

to be a delegate to the International Monetary Conference held in Brussels, Belgium, in 1892. As chairman of the House Committee on Foreign Affairs, he authored a bill to establish a court that would settle disputed land claims stemming from the Gadsden Purchase

and the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo. He advocated the creation of a railroad linking Canada, the United States, and Mexico. In 1890, he sponsored a bill authorizing the first Pan-American Conference

and was an advocate of the Pan-American Medical Conference that met in Washington, D.C., in 1893. He authored a report declaring American hostility to European ownership of a canal connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, and sponsored legislation authorizing the U.S. president to retaliate against foreign vessels that harassed American fishing boats.

In 1890, McCreary's name was again placed in nomination for a U.S. Senate seat to succeed James B. Beck

In 1890, McCreary's name was again placed in nomination for a U.S. Senate seat to succeed James B. Beck

, who died in office. John G. Carlisle, J. Proctor Knott, William Lindsay, Laban T. Moore

, and Evan E. Settle

were also nominated by various factions of the Democratic Party; Republicans nominated Silas Adams

. Carlisle was elected on the ninth ballot. McCreary continued his service in the House until 1896, when he was defeated in his bid for a seventh consecutive nomination for the seat. In that same year, his was among a myriad of names put forward for election to the Senate, but he never received more than 13 votes. Following these defeats, he resumed his law practice in Richmond.

McCreary campaigned for Democrat William Goebel

during the controversial 1899 gubernatorial campaign

. Between 1900 and 1912, he represented Kentucky at four consecutive Democratic National Convention

s. Governor J. C. W. Beckham and his well-established political machine

supported McCreary's nomination to the Senate in 1902. His opponent, incumbent William J. Deboe, had been elected as a compromise candidate six years earlier, becoming Kentucky's first-ever Republican senator. Deboe had done little to secure support from legislators since his election, however, and McCreary was easily elected by a vote of 95–30. Following his election to the Senate, McCreary supported Beckham's gubernatorial re-election bid in 1903. In a largely undistinguished term as a senator, he continued to advocate the free coinage of silver and tried to advance the state's agricultural interests.

McCreary's senate term was set to expire in 1908, the same year as Beckham's second term as governor. Desiring election to the Senate following his gubernatorial term, Beckham persuaded his Democratic allies to choose the party's nominees for governor and senator by a primary election

held in 1906 – a year before the gubernatorial election and two years before the senatorial election. This ensured that the primary would occur during his term as governor, when he still wielded significant influence within the party. McCreary now allied himself with J. C. S. Blackburn, Henry Watterson, and other Beckham opponents, and sought to defend his seat in the primary. During the primary campaign, he pointed to his record of dealing with national issues, contrasting it with Beckham's youth and inexperience at the national level. Beckham countered by citing his strong stand in favor of Prohibition

, as opposed to McCreary's more moderate position, and by touting his support of a primary election instead of a nominating convention, which he said gave the voters a choice in who would represent them in the Senate. Ultimately, Beckham prevailed in the primary by an 11,000-vote margin, rendering McCreary a lame duck

with two years still left in his term.

Republicans nominated Judge Edward C. O'Rear to oppose McCreary. There were few differences between the two men's stands on the issues. Both supported progressive

reforms such as the direct election

of senators, a non-partisan judiciary, and the creation of a public utilities commission

. McCreary also changed his stance on the liquor question, now agreeing with Beckham's prohibitionist position; this also matched the Republican position. O'Rear claimed that Democrats should have already enacted the reforms their party platform advocated, but his only ready line of attack against McCreary himself was that he would be a pawn of Beckham and his allies.

McCreary pointed out that O'Rear had been nominated at a party nominating convention instead of winning a primary, though O'Rear claimed to support primary elections. He also criticized O'Rear for continuing to receive his salary as a judge while running for governor. McCreary cited what he called the Republicans' record of "assassination, bloodshed, and disregard of law", an allusion to the assassination of William Goebel in the aftermath of the 1899 gubernatorial contest. Caleb Powers

, convicted three times of being an accessory to Goebel's murder, had been pardoned by Republican governor Augustus Willson and had recently been elected to Congress. He further attacked the tariff policies of Republican President William H. Taft. In the general election, McCreary won a decisive victory, garnering 226,771 votes to O'Rear's 195,435. Several other minor party candidates also received votes, including Socialist

candidate Walter Lanfersiek, who claimed 8,718 votes (2 percent of the total).

One of McCreary's first acts as governor was signing a bill appropriating $75,000 for the construction of a new governor's mansion

One of McCreary's first acts as governor was signing a bill appropriating $75,000 for the construction of a new governor's mansion

. The legislature appointed a commission of five, including McCreary, to oversee the mansion's construction. The governor exercised a good deal of influence over the process, including the replacement of a conservatory with a ballroom in the construction plan and the selection of a contractor from his hometown of Richmond as assistant superintendent of construction. Changing societal trends also affected construction. A hastily constructed stable to house horse-drawn carriages was soon abandoned in favor of a garage for automobiles.

The mansion was completed in 1914. Because McCreary was widowed before his second term in office, his granddaughter, Harriet Newberry McCreary, served as the mansion's first hostess during her summer vacations from her studies at Wellesley College. When Harriet McCreary was away at college, McCreary's housekeeper, Jennie Shaw, served as hostess. McCreary authorized the state to sell the old mansion at auction, but the final bid of $13,600 was rejected as unfair by the mansion commission.

s, and allowing the state's counties to hold local option

elections to decide whether or not to adopt prohibition. McCreary appointed a tax commission to study the revenue system, and the Board of Assessments and Valuation made a more realistic appraisal of corporate property. McCreary created executive departments to oversee state banking and highways, and a bipartisan vote in the General Assembly established the Kentucky Public Service Commission

. Near the close of the session, McCreary County

was created and named in the governor's honor. It was the last of Kentucky's 120 counties to be constituted.

McCreary was not as successful in securing reforms during the 1914 legislative session. He advocated a comprehensive workmen's compensation law, but the law that was passed in the 1914 General Assembly was later declared unconstitutional. He also recommended a requirement for full disclosure of campaign contributions and expenditures, but the majority of legislators in the House of Representatives voted to send it back to the Suffrage and Elections Committee, from whence it was never recalled. Although they did not pass a law regulating lobbying

at the capitol

– a law that McCreary supported – legislators showed responsiveness to McCreary's desire for this reform by putting stricter regulations on who could be in the legislative chambers while the legislature was in session. Some reforms were made in the area of education. The school year was lengthened, school attendance for children was mandated, and the legislature created a Text Book Commission to assist local school boards in adopting textbooks. Public schools expenditures were increased by 25 percent.

Part of the reason for the inefficacy of the 1914 session was that McCreary was engaged in a three-way primary race for the Democratic nomination to the U.S. Senate. The other major candidates were former Governor Beckham and Augustus O. Stanley

; a fourth candidate, David H. Smith, withdrew early from the race. McCreary ran a mostly positive campaign, touting his own accomplishments and speaking cordially about his opponents. Beckham and Stanley, however, were bitter political and personal enemies, and the campaign reflected their animosity. Without the support of Beckham's political machine that had helped him in the gubernatorial contest, McCreary never had a realistic chance to win the nomination. Beckham secured the nomination with 72,677 votes to Stanley's 65,871 and McCreary's 20,257.

Following the expiration of his term as governor, McCreary continued to practice as a private attorney until his death on October 8, 1918. He was buried in Richmond Cemetery.

Kentucky

The Commonwealth of Kentucky is a state located in the East Central United States of America. As classified by the United States Census Bureau, Kentucky is a Southern state, more specifically in the East South Central region. Kentucky is one of four U.S. states constituted as a commonwealth...

. He represented the state in both houses of the U.S. Congress

United States Congress

The United States Congress is the bicameral legislature of the federal government of the United States, consisting of the Senate and the House of Representatives. The Congress meets in the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C....

and served as its 27th and 37th governor

Governor of Kentucky

The Governor of the Commonwealth of Kentucky is the head of the executive branch of government in the U.S. state of Kentucky. Fifty-six men and one woman have served as Governor of Kentucky. The governor's term is four years in length; since 1992, incumbents have been able to seek re-election once...

. Shortly after graduating from law school, he was commissioned as the only major

Major (United States)

In the United States Army, Air Force, and Marine Corps, major is a field grade military officer rank just above the rank of captain and just below the rank of lieutenant colonel...

in the 11th Kentucky Cavalry, serving under Confederate

Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America was a government set up from 1861 to 1865 by 11 Southern slave states of the United States of America that had declared their secession from the U.S...

Brigadier General John Hunt Morgan

John Hunt Morgan

John Hunt Morgan was a Confederate general and cavalry officer in the American Civil War.Morgan is best known for Morgan's Raid when, in 1863, he and his men rode over 1,000 miles covering a region from Tennessee, up through Kentucky, into Indiana and on to southern Ohio...

during the American Civil War

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

. He returned to his legal practice after the war. In 1869, he was elected to the Kentucky House of Representatives

Kentucky House of Representatives

The Kentucky House of Representatives is the lower house of the Kentucky General Assembly. It is composed of 100 Representatives elected from single-member districts throughout the Commonwealth. Not more than two counties can be joined to form a House district, except when necessary to preserve...

where he served until 1875; he was twice chosen Speaker of the House. At their 1875 nominating convention, state Democrats

Democratic Party (United States)

The Democratic Party is one of two major contemporary political parties in the United States, along with the Republican Party. The party's socially liberal and progressive platform is largely considered center-left in the U.S. political spectrum. The party has the lengthiest record of continuous...

chose McCreary as their nominee for governor, and he won an easy victory over Republican

Republican Party (United States)

The Republican Party is one of the two major contemporary political parties in the United States, along with the Democratic Party. Founded by anti-slavery expansion activists in 1854, it is often called the GOP . The party's platform generally reflects American conservatism in the U.S...

John Marshall Harlan

John Marshall Harlan

John Marshall Harlan was a Kentucky lawyer and politician who served as an associate justice on the Supreme Court. He is most notable as the lone dissenter in the Civil Rights Cases , and Plessy v...

. With the state still feeling the effects of the Panic of 1873

Panic of 1873

The Panic of 1873 triggered a severe international economic depression in both Europe and the United States that lasted until 1879, and even longer in some countries. The depression was known as the Great Depression until the 1930s, but is now known as the Long Depression...

, most of McCreary's actions as governor were aimed at easing the plight of the state's poor farmers.

In 1884, McCreary was elected to the first of six consecutive terms in the U.S. House of Representatives

United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives is one of the two Houses of the United States Congress, the bicameral legislature which also includes the Senate.The composition and powers of the House are established in Article One of the Constitution...

. As a legislator, he was an advocate of free silver

Free Silver

Free Silver was an important United States political policy issue in the late 19th century and early 20th century. Its advocates were in favor of an inflationary monetary policy using the "free coinage of silver" as opposed to the less inflationary Gold Standard; its supporters were called...

and a champion of the state's agricultural interests. After two failed bids for election to the Senate

United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper house of the bicameral legislature of the United States, and together with the United States House of Representatives comprises the United States Congress. The composition and powers of the Senate are established in Article One of the U.S. Constitution. Each...

, McCreary secured the support of Governor J. C. W. Beckham

J. C. W. Beckham

John Crepps Wickliffe Beckham was the 35th Governor of Kentucky and a United States Senator from Kentucky...

, and in 1902, the General Assembly elected him to the Senate. He served one largely undistinguished term, and Beckham successfully challenged him for his Senate seat in 1908. The divide between McCreary and Beckham was short-lived, however, and Beckham supported McCreary's election to a second term as governor in 1911.

Campaigning on a platform of progressive

Progressivism in the United States

Progressivism in the United States is a broadly based reform movement that reached its height early in the 20th century and is generally considered to be middle class and reformist in nature. It arose as a response to the vast changes brought by modernization, such as the growth of large...

reforms, McCreary defeated Republican Edward C. O'Rear in the general election. During this second term, he became the first inhabitant of the state's second (and current) governor's mansion

Kentucky Governor's Mansion

The Kentucky Governor's Mansion is an historic residence in Frankfort, Kentucky. It is located at the East lawn of the Capitol, at the end of Capital Avenue...

; he is also the only governor to have inhabited both the old

Old Governor's Mansion (Frankfort, Kentucky)

The Old Governor's Mansion, also known as Lieutenant Governor's Mansion, is located at 420 High Street, Frankfort, Kentucky. It is reputed to be the oldest official executive residence officially still in use in the United States, as the mansion is the official residence of the Lieutenant Governor...

and new mansions. During his second term, he succeeded in convincing the legislature to make women eligible to vote in school board elections, to mandate direct primary election

Primary election

A primary election is an election in which party members or voters select candidates for a subsequent election. Primary elections are one means by which a political party nominates candidates for the next general election....

s, to create a state public utilities commission

Public Utilities Commission

A Utilities commission, Utility Regulatory Commission , Public Utilities Commission or Public Service Commission is a governing body that regulates the rates and services of a public utility...

, and to allow the state's counties to hold local option

Local Option

Local Option is a term used to describe the freedom whereby local political jurisdictions, typically counties or municipalities, can decide by popular vote certain controversial issues within their borders. In practice, it usually relates to the issue of alcoholic beverage sales...

elections to decide whether or not to adopt prohibition

Prohibition in the United States

Prohibition in the United States was a national ban on the sale, manufacture, and transportation of alcohol, in place from 1920 to 1933. The ban was mandated by the Eighteenth Amendment to the Constitution, and the Volstead Act set down the rules for enforcing the ban, as well as defining which...

. He also realized substantial increases in education spending and won passage of reforms such as a mandatory school attendance law, but was unable to secure passage of laws restricting lobbying in the legislative chambers and providing for a workers' compensation

Workers' compensation

Workers' compensation is a form of insurance providing wage replacement and medical benefits to employees injured in the course of employment in exchange for mandatory relinquishment of the employee's right to sue his or her employer for the tort of negligence...

program. McCreary was one of five commissioners charged with overseeing construction of the new governor's mansion and exerted considerable influence on the construction plans. His term expired in 1916, and he died two years later. McCreary County

McCreary County, Kentucky

McCreary County is a county located in the U.S. state of Kentucky. As of 2000, the population was 17,080. Its county seat is Whitley City. The county is named for James B. McCreary, a Confederate war hero and Governor of Kentucky from 1875 to 1879. It is the only Kentucky county to not have a...

was formed during McCreary's second term in office and was named in his honor.

Early life

James Bennett McCreary was born in Richmond, KentuckyRichmond, Kentucky

There were 10,795 households out of which 24.4% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 35.2% were married couples living together, 12.8% had a female householder with no husband present, and 48.6% were non-families. Of all households, 34.7% were made up of individuals and 8.8% had...

, on July 8, 1838. He was the son of Edmund R. and Sabrina (Bennett) McCreary. He obtained his early education in the region's common schools, then matriculated to Centre College

Centre College

Centre College is a private liberal arts college in Danville, Kentucky, USA, a community of approximately 16,000 in Boyle County south of Lexington, KY. Centre is an exclusively undergraduate four-year institution. Centre was founded by Presbyterian leaders, with whom it maintains a loose...

in Danville, Kentucky

Danville, Kentucky

Danville is a city in and the county seat of Boyle County, Kentucky, United States. The population was 16,218 at the 2010 census.Danville is the principal city of the Danville Micropolitan Statistical Area, which includes all of Boyle and Lincoln counties....

, where he earned a bachelor's degree in 1857. Immediately thereafter, he enrolled at Cumberland University

Cumberland University

Cumberland University is a private university in Lebanon, Tennessee, United States. It was founded in 1842, though the current campus buildings were constructed between 1892 and 1896.-History:...

in Lebanon, Tennessee

Lebanon, Tennessee

Lebanon is a city in Wilson County, Tennessee, in the United States. The population was 20,235 at the 2000 census. It serves as the county seat of Wilson County. Lebanon is located in middle Tennessee, approximately 25 miles east of downtown Nashville. Local residents have also called it...

, to study law. In 1859, he earned a Bachelor of Laws

Bachelor of Laws

The Bachelor of Laws is an undergraduate, or bachelor, degree in law originating in England and offered in most common law countries as the primary law degree...

from Cumberland and was valedictorian

Valedictorian

Valedictorian is an academic title conferred upon the student who delivers the closing or farewell statement at a graduation ceremony. Usually, the valedictorian is the highest ranked student among those graduating from an educational institution...

of his class of forty-seven students; he was admitted to the bar

Bar (law)

Bar in a legal context has three possible meanings: the division of a courtroom between its working and public areas; the process of qualifying to practice law; and the legal profession.-Courtroom division:...

and commenced practice at Richmond.

Shortly after the Battle of Richmond on August 29, 1862, David Waller Chenault, a Confederate sympathizer from Madison County

Madison County, Kentucky

Madison County is a county located in the U.S. state of Kentucky. As of 2008, the population was 82,192. Its county seat is Richmond. The county is named for Virginia statesman James Madison, who later became the fourth President of the United States. This is also where famous pioneer Daniel...

, came to Richmond to raise a Confederate regiment. On September 10, 1862, Chenault was commissioned as a colonel

Colonel (United States)

In the United States Army, Air Force, and Marine Corps, colonel is a senior field grade military officer rank just above the rank of lieutenant colonel and just below the rank of brigadier general...

and given command of the regiment, dubbed the 11th Kentucky Cavalry. McCreary joined the regiment and was commissioned as a major

Major (United States)

In the United States Army, Air Force, and Marine Corps, major is a field grade military officer rank just above the rank of captain and just below the rank of lieutenant colonel...

, the only one in the unit. The 11th Kentucky Cavalry was pressed into immediate service, conducting reconnaissance

Reconnaissance

Reconnaissance is the military term for exploring beyond the area occupied by friendly forces to gain information about enemy forces or features of the environment....

and fighting bushwhacker

Bushwhacker

Bushwhacking was a form of guerrilla warfare common during the American Revolutionary War, American Civil War and other conflicts in which there are large areas of contested land and few Governmental Resources to control these tracts...

s. Just three months after its muster, they helped the Confederate Army

Confederate States Army

The Confederate States Army was the army of the Confederate States of America while the Confederacy existed during the American Civil War. On February 8, 1861, delegates from the seven Deep South states which had already declared their secession from the United States of America adopted the...

secure a victory at the Battle of Hartsville

Battle of Hartsville

The Battle of Hartsville was fought on December 7, 1862, in northern Tennessee at the opening of the Stones River Campaign the American Civil War.-Background:...

. In 1863, the unit joined John Hunt Morgan

John Hunt Morgan

John Hunt Morgan was a Confederate general and cavalry officer in the American Civil War.Morgan is best known for Morgan's Raid when, in 1863, he and his men rode over 1,000 miles covering a region from Tennessee, up through Kentucky, into Indiana and on to southern Ohio...

for his raid into Ohio

Morgan's Raid

Morgan's Raid was a highly publicized incursion by Confederate cavalry into the Northern states of Indiana and Ohio during the American Civil War. The raid took place from June 11–July 26, 1863, and is named for the commander of the Confederates, Brig. Gen...

. Colonel Chenault was killed as the Confederates tried to capture the Green River

Green River (Kentucky)

The Green River is a tributary of the Ohio River that rises in Lincoln County in south-central Kentucky. Tributaries of the Green River include the Barren River, the Nolin River, the Pond River and the Rough River...

Bridge at the July 4, 1863, Battle of Tebbs Bend

Battle of Tebbs Bend

The Battle of Tebbs' Bend was fought on July 4, 1863, near the Green River in Taylor County, Kentucky during Morgan's Raid in the American Civil War. Despite being badly outnumbered, elements of the Union army thwarted repeated attacks by Confederate Brig. Gen...

. McCreary assumed command of the unit after Chenault's death. Following the battle, he was promoted to the rank of lieutenant colonel on the recommendation of John C. Breckinridge

John C. Breckinridge

John Cabell Breckinridge was an American lawyer and politician. He served as a U.S. Representative and U.S. Senator from Kentucky and was the 14th Vice President of the United States , to date the youngest vice president in U.S...

.

Most of the 11th Kentucky Cavalry was captured by Union forces

Union Army

The Union Army was the land force that fought for the Union during the American Civil War. It was also known as the Federal Army, the U.S. Army, the Northern Army and the National Army...

at the Battle of Buffington Island

Battle of Buffington Island

The Battle of Buffington Island, also known as the St. Georges Creek Skirmish, was an American Civil War engagement in Meigs County, Ohio, and Jackson County, West Virginia, on July 19, 1863, during Morgan's Raid. The largest battle in Ohio during the war, Buffington Island contributed to the...

on July 17, 1863. Approximately two hundred men, commanded by McCreary, mounted a charge and escaped their captors, but they were surrounded the next day and surrendered. McCreary was taken to Ninth Street Prison in Cincinnati, Ohio, but was later transferred to Fort Delaware

Fort Delaware

Fort Delaware is a harbor defense facility, designed by Chief Engineer Joseph Gilbert Totten, and located on Pea Patch Island in the Delaware River. During the American Civil War, the Union used Fort Delaware as a prison for Confederate prisoners of war, political prisoners, federal convicts, and...

and eventually to Morris Island

Morris Island

Morris Island is an 840 acre uninhabited island in Charleston Harbor in South Carolina, accessible only by boat. The island lies in the outer reaches of the harbor and was thus a strategic location in the American Civil War.-History:...

, South Carolina

South Carolina

South Carolina is a state in the Deep South of the United States that borders Georgia to the south, North Carolina to the north, and the Atlantic Ocean to the east. Originally part of the Province of Carolina, the Province of South Carolina was one of the 13 colonies that declared independence...

, where he remained a prisoner through July and most of August 1863. In late August, he was released as part of a prisoner exchange

Prisoner exchange

A prisoner exchange or prisoner swap is a deal between opposing sides in a conflict to release prisoners. These may be prisoners of war, spies, hostages, etc...

and taken to Richmond, Virginia

Richmond, Virginia

Richmond is the capital of the Commonwealth of Virginia, in the United States. It is an independent city and not part of any county. Richmond is the center of the Richmond Metropolitan Statistical Area and the Greater Richmond area...

. He was granted a thirty-day furlough

Furlough

In the United States a furlough is a temporary unpaid leave of some employees due to special needs of a company, which may be due to economic conditions at the specific employer or in the economy as a whole...

before being put in command of a battalion

Battalion

A battalion is a military unit of around 300–1,200 soldiers usually consisting of between two and seven companies and typically commanded by either a Lieutenant Colonel or a Colonel...

of Kentucky and South Carolina troops. He commanded this unit, primarily on scouting missions, until the end of the war.

Following the war, McCreary resumed his legal practice. On June 12, 1867, McCreary married Katherine Hughes, the only daughter of a wealthy Fayette County

Fayette County, Kentucky

Fayette County is a county located in the U.S. state of Kentucky. The population was 295,083 in the 2010 Census. Its territory, population and government are coextensive with the city of Lexington, which also serves as county seat....

farmer. The couple had one son.

Early political career

McCreary was nominated to serve as a presidential electorUnited States Electoral College

The Electoral College consists of the electors appointed by each state who formally elect the President and Vice President of the United States. Since 1964, there have been 538 electors in each presidential election...

for the ticket of Democrat Horatio Seymour

Horatio Seymour

Horatio Seymour was an American politician. He was the 18th Governor of New York from 1853 to 1854 and from 1863 to 1864. He was the Democratic Party nominee for president of the United States in the presidential election of 1868, but lost the election to Republican and former Union General of...

in 1868; though he declined to serve, he attended the national convention

1868 Democratic National Convention

The 1868 Democratic National Convention was held at Tammany Hall in New York City. Although former Governor from New York Horatio Seymour was nominated as the unanimous candidate for President, he stood virtually no chance of defeating the hero of the Civil War, Republican candidate Ulysses S. Grant...

as a delegate. His political career began in earnest in 1869 when he was elected to the Kentucky House of Representatives

Kentucky House of Representatives

The Kentucky House of Representatives is the lower house of the Kentucky General Assembly. It is composed of 100 Representatives elected from single-member districts throughout the Commonwealth. Not more than two counties can be joined to form a House district, except when necessary to preserve...

.

In 1871, McCreary was re-elected to the state House without opposition. In the upcoming legislative session, the major question was expected to be the Cincinnati Southern Railway

Cincinnati, New Orleans and Texas Pacific Railway

The Cincinnati, New Orleans and Texas Pacific Railway is a railroad that runs from Cincinnati, Ohio, south to Chattanooga, Tennessee, forming part of the Norfolk Southern Railway system. The rail line that it operates, the Cincinnati Southern Railway, is owned by the City of Cincinnati and is...

's request for authorization to build a track connecting Cincinnati, Ohio, with either Knoxville

Knoxville, Tennessee

Founded in 1786, Knoxville is the third-largest city in the U.S. state of Tennessee, U.S.A., behind Memphis and Nashville, and is the county seat of Knox County. It is the largest city in East Tennessee, and the second-largest city in the Appalachia region...

or Chattanooga, Tennessee

Chattanooga, Tennessee

Chattanooga is the fourth-largest city in the US state of Tennessee , with a population of 169,887. It is the seat of Hamilton County...

, through Central Kentucky

Central Kentucky

Central Kentucky is sometimes considered the Central and Southern part of the Bluegrass region, the Far Upper Western Eastern Mountain Coal Fields, and the Far Upper Eastern Pennyroyal regions. Its major cities include Lexington and Frankfort. Lexington citizens, especially radio and TV stations...

. The action was opposed by the Louisville and Nashville Railroad

Louisville and Nashville Railroad

The Louisville and Nashville Railroad was a Class I railroad that operated freight and passenger services in the southeast United States.Chartered by the state of Kentucky in 1850, the L&N, as it was generally known, grew into one of the great success stories of American business...

, a bitter rival of the Cincinnati line. Appeals to the General Assembly

Kentucky General Assembly

The Kentucky General Assembly, also called the Kentucky Legislature, is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Kentucky.The General Assembly meets annually in the state capitol building in Frankfort, Kentucky, convening on the first Tuesday after the first Monday in January...

to oppose the bill on grounds that an out-of-state corporation should not be granted a charter in the state were successful in 1869 and 1870, and an attempt by the federal Congress to grant the charter was defeated by states' rights

States' rights

States' rights in U.S. politics refers to political powers reserved for the U.S. state governments rather than the federal government. It is often considered a loaded term because of its use in opposition to federally mandated racial desegregation...

legislators there. Moreover, newly elected governor Preston Leslie

Preston Leslie

Preston Hopkins Leslie was the 26th Governor of Kentucky from 1871 to 1875 and territorial governor of Montana from 1887 to 1889. He ascended to the office of governor by three different means. First, he succeeded Kentucky governor John W. Stevenson upon the latter's resignation to accept a seat...

had opposed a bill granting Cincinnati Southern's request when he was in the state Senate

Kentucky Senate

The Kentucky Senate is the upper house of the Kentucky General Assembly. The Kentucky Senate is composed of 38 members elected from single-member districts throughout the Commonwealth. There are no term limits for Kentucky Senators...

in 1869. In the lead-up to the 1871 session, frustrated Central Kentuckians threatened to defect from the Democratic Party in future elections if the bill were not passed in the session. Supporters of Cincinnati Southern won a victory when McCreary, a staunch supporter of the bill to grant the line's request, was elected Speaker of the House. After approval of a series of amendments designed to give Kentucky courts some jurisdiction in cases involving the line and the Kentucky General Assembly some measure of control over the line's activities, the bill passed the House by a vote of 59–38. The vote in the Senate resulted in a 19–19 tie; President Pro Tem

President Pro Tempore of the Kentucky Senate

President Pro Tempore of the Kentucky Senate was the title of highest ranking member of the Kentucky Senate prior to enactment of a 1992 amendment to the Constitution of Kentucky....

John G. Carlisle—a native of Covington

Covington, Kentucky

-Demographics:As of the census of 2000, there were 43,370 people, 18,257 households, and 10,132 families residing in the city. The population density was 3,301.3 people per square mile . There were 20,448 housing units at an average density of 1,556.5 per square mile...

, through which the proposed line would pass—cast the deciding vote in favor of approving Cincinnati Southern's request. With the will of the people clearly expressed through the legislature, Governor Leslie did not employ his gubernatorial veto. McCreary was again returned to the House without opposition in 1873 and was again chosen Speaker of the House during his term.

First term as governor

In 1875, McCreary was one of four men, all former Confederate soldiers, who sought the Democratic gubernatorial nomination—the others being John Stuart WilliamsJohn Stuart Williams

John Stuart Williams was a general in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War and a postbellum Democratic U.S. Senator from Kentucky.-Early life and career:...

, J. Stoddard Johnson, and George B. Hodge. Williams was considered the favorite for the nomination at the outset of the Democratic nominating convention, despite attacks on his character by newspapers in the western part of the state. However, McCreary defeated Williams on the fourth ballot.

John Marshall Harlan

John Marshall Harlan was a Kentucky lawyer and politician who served as an associate justice on the Supreme Court. He is most notable as the lone dissenter in the Civil Rights Cases , and Plessy v...

, who had served in the Union Army. In joint debates across the state, McCreary stressed what many Kentuckians felt were abuses of power by Republican President Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant was the 18th President of the United States as well as military commander during the Civil War and post-war Reconstruction periods. Under Grant's command, the Union Army defeated the Confederate military and ended the Confederate States of America...

during the Reconstruction Era. Harlan countered by faulting the state's Democratic politicians for continuing to dwell on war issues almost a decade after the war's end. He also attacked what he perceived as Democratic financial extravagance and the high number of pardons granted by sitting Democratic governor Preston Leslie. Harlan claimed these as evidence of widespread corruption in the Democratic Party. McCreary received solid support from the state's newspapers, nearly all of which had Democratic sympathies. Despite a late infusion of cash and stump speakers in favor of his opponent, McCreary won the general election by a vote of 130,026 to 94,236.

At the time of McCreary's election, his wife Kate was the youngest first lady in the Commonwealth's history. Due to the near completion of an annex to the state capitol building by the time of McCreary's inauguration, he was able to move the official governor's office out of the governor's mansion

Old Governor's Mansion (Frankfort, Kentucky)

The Old Governor's Mansion, also known as Lieutenant Governor's Mansion, is located at 420 High Street, Frankfort, Kentucky. It is reputed to be the oldest official executive residence officially still in use in the United States, as the mansion is the official residence of the Lieutenant Governor...

, freeing his family from the intrusion of public business into their private quarters. McCreary's receipt of the executive journal and Great Seal of the Commonwealth from outgoing Governor Leslie in the mansion's office is believed to be the last official act performed by a governor there.

In the wake of the Panic of 1873

Panic of 1873

The Panic of 1873 triggered a severe international economic depression in both Europe and the United States that lasted until 1879, and even longer in some countries. The depression was known as the Great Depression until the 1930s, but is now known as the Long Depression...

, the electorate was primarily concerned with economic issues. In his first address to the General Assembly, McCreary focused on economic issues to the near exclusion of providing any leadership or direction in the area of government reforms. (In later years, McCreary's unwillingness to take a definite stand on key issues of reform would earn him the nicknames "Bothsides" McCreary and "Oily Jeems".) In response to McCreary's address, legislators from the rural, agrarian areas of the state proposed lowering the maximum legal interest rate from ten percent to six percent. The proposed legislation drew the ire of bankers and capitalists; it was also widely panned in the press, notably by Louisville Courier-Journal editor Henry Watterson

Henry Watterson

Henry Watterson was a United States journalist who founded the Louisville Courier-Journal.He also served part of one term in the United States House of Representatives as a Democrat....

. Ultimately, the Assembly compromised on a legal interest rate of eight percent. Another bill to lower the property tax

Property tax

A property tax is an ad valorem levy on the value of property that the owner is required to pay. The tax is levied by the governing authority of the jurisdiction in which the property is located; it may be paid to a national government, a federated state or a municipality...

rate from 45 to 40 cents per 100 dollars of taxable property encountered far less resistance and passed easily. Few bills passed during the session had statewide impact, despite McCreary's insistence that the legislature prefer general bills over bills of local impact. This fact, too, was widely criticized by the state's newspapers.

The issue of improving navigation along the Kentucky River

Kentucky River

The Kentucky River is a tributary of the Ohio River, long, in the U.S. state of Kentucky. The river and its tributaries drain much of the central region of the state, with its upper course passing through the coal-mining regions of the Cumberland Mountains, and its lower course passing through the...

was raised numerous times by Representative James Blue during the 1876 legislative session. Despite Blue's promises of manifold benefits to the state from such an investment, parsimonious legislators defeated a bill allocating funds for the improvements. The issue gained traction with some voters during the biennial legislative elections, however, which brought it back to the floor in the 1878 session. Prompted by recommendations from the Kentucky River Navigation Convention in 1877, McCreary abandoned his typical fiscal conservatism and joined the calls for improvements along the river. In response, legislators passed a largely ineffective bill providing that, if funds could be raised through special taxes in districts along the river, the state would provide the funds to maintain the improvements.

Also in the 1878 session, tax assessments for railroad property were raised to match those of other property. Agrarian interests were pleased that the legal interest rate was again lowered, now reaching the six percent they had proposed in the previous session. Non-economic reforms included the separation of Kentucky Agricultural and Mechanical College (later the University of Kentucky

University of Kentucky

The University of Kentucky, also known as UK, is a public co-educational university and is one of the state's two land-grant universities, located in Lexington, Kentucky...

) from Kentucky University (later Transylvania University

Transylvania University

Transylvania University is a private, undergraduate liberal arts college in Lexington, Kentucky, United States, affiliated with the Christian Church . The school was founded in 1780. It offers 38 majors, and pre-professional degrees in engineering and accounting...

) and the establishment of a state board of health. Bills of local import again dominated the session, representing 90 percent of the acts and resolutions passed by the Assembly.

Along with Democrats John Stuart Williams, William Lindsay, and J. Proctor Knott

J. Proctor Knott

James Proctor Knott was a U.S. Representative from Kentucky and served as the 29th Governor of Kentucky from 1883 to 1887. Born in Kentucky, he moved to Missouri in 1850 and began his political career there...

, and Republican Robert Boyd, McCreary was nominated for a U.S. Senate

United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper house of the bicameral legislature of the United States, and together with the United States House of Representatives comprises the United States Congress. The composition and powers of the Senate are established in Article One of the U.S. Constitution. Each...

seat in 1878. Democrats were divided by sectionalism and initially unable to unite behind one of their four candidates. After more than a week of caucus

Caucus

A caucus is a meeting of supporters or members of a political party or movement, especially in the United States and Canada. As the use of the term has been expanded the exact definition has come to vary among political cultures.-Origin of the term:...

ing among Democratic legislators, the nominations of McCreary, Knott, and Lindsay were withdrawn, and Williams was elected over Boyd. Historian Hambleton Tapp opined that the withdrawals were likely a part of some kind of deal among legislators, although the details of the deal, if it ever existed, were not made public.

Service in Congress

Following his term as governor, McCreary returned to his legal practice. In 1884, he sought election to Congress from Kentucky's Eighth DistrictKentucky's 8th congressional district

United States House of Representatives, Kentucky District 8 was a district of the United States Congress in Kentucky. It was lost to redistricting in 1963. Its last Representative was Eugene Siler.-List of representatives:-References:*...

. His opponents for the Democratic nomination were Milton J. Durham

Milton J. Durham

Milton Jameson Durham was a U.S. Representative from Kentucky and served as First Comptroller of the Treasury in the administration of President Grover Cleveland...

and Philip B. Thompson, Jr.

Philip B. Thompson, Jr.

Philip Burton Thompson, Jr. was a U.S. Representative from Kentucky.Born in Harrodsburg, Kentucky, Thompson attended the common schools and the University of Kentucky in Lexington, Kentucky....

, both of whom had held the district's seat previously. McCreary bested both men, and in the general election in November, defeated Republican James Sebastian by a margin of 2,146 votes. It was the largest margin of victory by a Democrat in the Eighth District.

During his tenure, McCreary represented Kentucky's agricultural interests, introducing a bill to create the United States Department of Agriculture

United States Department of Agriculture

The United States Department of Agriculture is the United States federal executive department responsible for developing and executing U.S. federal government policy on farming, agriculture, and food...

. A bill containing most of the same provisions as the one McCreary authored was passed later in the session. He also proposed a successful amendment to the Wilson–Gorman Tariff Act that excluded farm implements and machinery from the tariff. An advocate of free silver

Free Silver

Free Silver was an important United States political policy issue in the late 19th century and early 20th century. Its advocates were in favor of an inflationary monetary policy using the "free coinage of silver" as opposed to the less inflationary Gold Standard; its supporters were called...

, he was appointed by President Benjamin Harrison

Benjamin Harrison

Benjamin Harrison was the 23rd President of the United States . Harrison, a grandson of President William Henry Harrison, was born in North Bend, Ohio, and moved to Indianapolis, Indiana at age 21, eventually becoming a prominent politician there...

to be a delegate to the International Monetary Conference held in Brussels, Belgium, in 1892. As chairman of the House Committee on Foreign Affairs, he authored a bill to establish a court that would settle disputed land claims stemming from the Gadsden Purchase

Gadsden Purchase

The Gadsden Purchase is a region of present-day southern Arizona and southwestern New Mexico that was purchased by the United States in a treaty signed by James Gadsden, the American ambassador to Mexico at the time, on December 30, 1853. It was then ratified, with changes, by the U.S...

and the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo. He advocated the creation of a railroad linking Canada, the United States, and Mexico. In 1890, he sponsored a bill authorizing the first Pan-American Conference

Pan-American Conference

The Conferences of American States, commonly referred to as the Pan-American Conferences, were meetings of the Pan-American Union, an international organization for cooperation on trade and other issues. They were first introduced by James G. Blaine of Maine in order to establish closer ties...

and was an advocate of the Pan-American Medical Conference that met in Washington, D.C., in 1893. He authored a report declaring American hostility to European ownership of a canal connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, and sponsored legislation authorizing the U.S. president to retaliate against foreign vessels that harassed American fishing boats.

James B. Beck

James Burnie Beck was a United States Representative and Senator from Kentucky.Born in Dumfriesshire, Scotland, Beck immigrated to the United States in 1838 and settled in Wyoming County, New York. He moved to Lexington, Kentucky in 1843 and graduated from Transylvania University in 1846...

, who died in office. John G. Carlisle, J. Proctor Knott, William Lindsay, Laban T. Moore

Laban T. Moore

Laban Theodore Moore was a U.S. Representative from Kentucky.Born in Wayne County, Virginia , near Louisa, Kentucky, Moore attended Marshall Academy in Virginia and was graduated from Marietta College in Ohio.He attended Transylvania Law College at Lexington.He was admitted to the bar in 1849 and...

, and Evan E. Settle

Evan E. Settle

Evan Evans Settle was a U.S. Representative from Kentucky.Born in Frankfort, Kentucky, Settle attended the public schools.He was graduated from Louisville High School in June 1864.He studied law....

were also nominated by various factions of the Democratic Party; Republicans nominated Silas Adams

Silas Adams

Silas Adams was a lawyer and politician from Kentucky.-Youth:He was born in Pulaski County, Kentucky on February 9, 1839, and moved to Casey County with his parents in 1841...

. Carlisle was elected on the ninth ballot. McCreary continued his service in the House until 1896, when he was defeated in his bid for a seventh consecutive nomination for the seat. In that same year, his was among a myriad of names put forward for election to the Senate, but he never received more than 13 votes. Following these defeats, he resumed his law practice in Richmond.

McCreary campaigned for Democrat William Goebel

William Goebel

William Justus Goebel was an American politician who served as the 34th Governor of Kentucky for a few days in 1900 after having been mortally wounded by an assassin the day before he was sworn in...

during the controversial 1899 gubernatorial campaign

Kentucky gubernatorial election, 1899

The Kentucky gubernatorial election of 1899 was held on November 7, 1899, to choose the 33rd governor of Kentucky. The incumbent, Republican William O'Connell Bradley, was term-limited and unable to seek re-election....

. Between 1900 and 1912, he represented Kentucky at four consecutive Democratic National Convention

Democratic National Convention

The Democratic National Convention is a series of presidential nominating conventions held every four years since 1832 by the United States Democratic Party. They have been administered by the Democratic National Committee since the 1852 national convention...

s. Governor J. C. W. Beckham and his well-established political machine

Political machine

A political machine is a political organization in which an authoritative boss or small group commands the support of a corps of supporters and businesses , who receive rewards for their efforts...

supported McCreary's nomination to the Senate in 1902. His opponent, incumbent William J. Deboe, had been elected as a compromise candidate six years earlier, becoming Kentucky's first-ever Republican senator. Deboe had done little to secure support from legislators since his election, however, and McCreary was easily elected by a vote of 95–30. Following his election to the Senate, McCreary supported Beckham's gubernatorial re-election bid in 1903. In a largely undistinguished term as a senator, he continued to advocate the free coinage of silver and tried to advance the state's agricultural interests.

McCreary's senate term was set to expire in 1908, the same year as Beckham's second term as governor. Desiring election to the Senate following his gubernatorial term, Beckham persuaded his Democratic allies to choose the party's nominees for governor and senator by a primary election

Primary election

A primary election is an election in which party members or voters select candidates for a subsequent election. Primary elections are one means by which a political party nominates candidates for the next general election....

held in 1906 – a year before the gubernatorial election and two years before the senatorial election. This ensured that the primary would occur during his term as governor, when he still wielded significant influence within the party. McCreary now allied himself with J. C. S. Blackburn, Henry Watterson, and other Beckham opponents, and sought to defend his seat in the primary. During the primary campaign, he pointed to his record of dealing with national issues, contrasting it with Beckham's youth and inexperience at the national level. Beckham countered by citing his strong stand in favor of Prohibition

Prohibition in the United States

Prohibition in the United States was a national ban on the sale, manufacture, and transportation of alcohol, in place from 1920 to 1933. The ban was mandated by the Eighteenth Amendment to the Constitution, and the Volstead Act set down the rules for enforcing the ban, as well as defining which...

, as opposed to McCreary's more moderate position, and by touting his support of a primary election instead of a nominating convention, which he said gave the voters a choice in who would represent them in the Senate. Ultimately, Beckham prevailed in the primary by an 11,000-vote margin, rendering McCreary a lame duck

Lame duck (politics)

A lame duck is an elected official who is approaching the end of his or her tenure, and especially an official whose successor has already been elected.-Description:The status can be due to*having lost a re-election bid...

with two years still left in his term.

Second term as governor and death

Despite Beckham's move to unseat McCreary in the Senate, the two were once again allies by 1911, when Beckham supported the aging McCreary for the party's gubernatorial nomination. It is unclear whether McCreary sought the reconciliation in order to secure the gubernatorial nomination or Beckham made amends with McCreary because he thought he could control McCreary's actions as governor. In the Democratic primary, McCreary defeated William Adams by a majority of 25,000 votes.Republicans nominated Judge Edward C. O'Rear to oppose McCreary. There were few differences between the two men's stands on the issues. Both supported progressive

Progressivism in the United States

Progressivism in the United States is a broadly based reform movement that reached its height early in the 20th century and is generally considered to be middle class and reformist in nature. It arose as a response to the vast changes brought by modernization, such as the growth of large...

reforms such as the direct election

Direct election

Direct election is a term describing a system of choosing political officeholders in which the voters directly cast ballots for the person, persons or political party that they desire to see elected. The method by which the winner or winners of a direct election are chosen depends upon the...

of senators, a non-partisan judiciary, and the creation of a public utilities commission

Public Utilities Commission

A Utilities commission, Utility Regulatory Commission , Public Utilities Commission or Public Service Commission is a governing body that regulates the rates and services of a public utility...

. McCreary also changed his stance on the liquor question, now agreeing with Beckham's prohibitionist position; this also matched the Republican position. O'Rear claimed that Democrats should have already enacted the reforms their party platform advocated, but his only ready line of attack against McCreary himself was that he would be a pawn of Beckham and his allies.

McCreary pointed out that O'Rear had been nominated at a party nominating convention instead of winning a primary, though O'Rear claimed to support primary elections. He also criticized O'Rear for continuing to receive his salary as a judge while running for governor. McCreary cited what he called the Republicans' record of "assassination, bloodshed, and disregard of law", an allusion to the assassination of William Goebel in the aftermath of the 1899 gubernatorial contest. Caleb Powers

Caleb Powers

Caleb Powers was a United States Representative from Kentucky and the first Secretary of State of Kentucky convicted as an accessory to murder.-Early life:He was born near Williamsburg, Kentucky...

, convicted three times of being an accessory to Goebel's murder, had been pardoned by Republican governor Augustus Willson and had recently been elected to Congress. He further attacked the tariff policies of Republican President William H. Taft. In the general election, McCreary won a decisive victory, garnering 226,771 votes to O'Rear's 195,435. Several other minor party candidates also received votes, including Socialist

Socialist Party of America

The Socialist Party of America was a multi-tendency democratic-socialist political party in the United States, formed in 1901 by a merger between the three-year-old Social Democratic Party of America and disaffected elements of the Socialist Labor Party which had split from the main organization...

candidate Walter Lanfersiek, who claimed 8,718 votes (2 percent of the total).

Construction of the new governor's mansion

Kentucky Governor's Mansion

The Kentucky Governor's Mansion is an historic residence in Frankfort, Kentucky. It is located at the East lawn of the Capitol, at the end of Capital Avenue...

. The legislature appointed a commission of five, including McCreary, to oversee the mansion's construction. The governor exercised a good deal of influence over the process, including the replacement of a conservatory with a ballroom in the construction plan and the selection of a contractor from his hometown of Richmond as assistant superintendent of construction. Changing societal trends also affected construction. A hastily constructed stable to house horse-drawn carriages was soon abandoned in favor of a garage for automobiles.

The mansion was completed in 1914. Because McCreary was widowed before his second term in office, his granddaughter, Harriet Newberry McCreary, served as the mansion's first hostess during her summer vacations from her studies at Wellesley College. When Harriet McCreary was away at college, McCreary's housekeeper, Jennie Shaw, served as hostess. McCreary authorized the state to sell the old mansion at auction, but the final bid of $13,600 was rejected as unfair by the mansion commission.

Progressive reforms

Among the progressive reforms advocated by McCreary and passed in the 1912 legislative session were making women eligible to vote in school board elections, mandating direct primary electionPrimary election

A primary election is an election in which party members or voters select candidates for a subsequent election. Primary elections are one means by which a political party nominates candidates for the next general election....

s, and allowing the state's counties to hold local option

Local Option

Local Option is a term used to describe the freedom whereby local political jurisdictions, typically counties or municipalities, can decide by popular vote certain controversial issues within their borders. In practice, it usually relates to the issue of alcoholic beverage sales...

elections to decide whether or not to adopt prohibition. McCreary appointed a tax commission to study the revenue system, and the Board of Assessments and Valuation made a more realistic appraisal of corporate property. McCreary created executive departments to oversee state banking and highways, and a bipartisan vote in the General Assembly established the Kentucky Public Service Commission

Kentucky Public Service Commission

The Kentucky Public Service Commission is a public utilities commission, a quasi-judicial regulatory tribunal, whichregulates the intrastate rates and services of investor-owned electric, natural gas, telephone, water and sewage utilities, customer-owned electric and telephone cooperatives, water...

. Near the close of the session, McCreary County

McCreary County, Kentucky

McCreary County is a county located in the U.S. state of Kentucky. As of 2000, the population was 17,080. Its county seat is Whitley City. The county is named for James B. McCreary, a Confederate war hero and Governor of Kentucky from 1875 to 1879. It is the only Kentucky county to not have a...

was created and named in the governor's honor. It was the last of Kentucky's 120 counties to be constituted.

McCreary was not as successful in securing reforms during the 1914 legislative session. He advocated a comprehensive workmen's compensation law, but the law that was passed in the 1914 General Assembly was later declared unconstitutional. He also recommended a requirement for full disclosure of campaign contributions and expenditures, but the majority of legislators in the House of Representatives voted to send it back to the Suffrage and Elections Committee, from whence it was never recalled. Although they did not pass a law regulating lobbying

Lobbying in the United States

Lobbying in the United States targets the United States Senate, the United States House of Representatives, and state legislatures. Lobbyists may also represent their clients' or organizations' interests in dealings with federal, state, or local executive branch agencies or the courts. Lobby...

at the capitol

Kentucky State Capitol

The Kentucky State Capitol is located in Frankfort and is the house of the three branches of the state government of the Commonwealth of Kentucky...

– a law that McCreary supported – legislators showed responsiveness to McCreary's desire for this reform by putting stricter regulations on who could be in the legislative chambers while the legislature was in session. Some reforms were made in the area of education. The school year was lengthened, school attendance for children was mandated, and the legislature created a Text Book Commission to assist local school boards in adopting textbooks. Public schools expenditures were increased by 25 percent.

Part of the reason for the inefficacy of the 1914 session was that McCreary was engaged in a three-way primary race for the Democratic nomination to the U.S. Senate. The other major candidates were former Governor Beckham and Augustus O. Stanley

Augustus O. Stanley

Augustus Owsley Stanley I was a politician from the US state of Kentucky. A Democrat, he served as the 38th Governor of Kentucky and also represented the state in both the U.S. House of Representatives and the U.S. Senate...

; a fourth candidate, David H. Smith, withdrew early from the race. McCreary ran a mostly positive campaign, touting his own accomplishments and speaking cordially about his opponents. Beckham and Stanley, however, were bitter political and personal enemies, and the campaign reflected their animosity. Without the support of Beckham's political machine that had helped him in the gubernatorial contest, McCreary never had a realistic chance to win the nomination. Beckham secured the nomination with 72,677 votes to Stanley's 65,871 and McCreary's 20,257.