Nadir of American race relations

Encyclopedia

The "nadir of American race relations" is a term that refers to the period in United States history

from the end of Reconstruction through the early 20th century, when racism

in the country is deemed to have been worse than in any other period after the American Civil War

. During this period, African American

s lost many civil rights

gains made during Reconstruction. Anti-black violence, lynching

s, segregation

, legal racial discrimination

, and expressions of white supremacy

increased.

Historian Rayford Logan

first used the phrase "the nadir" to describe this period in his 1954 book The Negro in American Life and Thought: The Nadir, 1877-1901. The phrase continues to be used, most notably in the books of James Loewen

, but also by other scholars. Loewen argued that the post-Reconstruction period was actually one of widespread hope for racial equity, when idealistic Northerners

championed civil rights. The true nadir, accordingly, began only when northern Republicans

ceased supporting southern black rights around 1890, and extended through 1940. This period followed the financial Panic of 1873

and a continuing decline in agriculture, and coincided with American imperialist aspirations, the Progressive Era

, and the sundown town

phenomenon across the country.

In the early part of the 20th century, white Southerners

In the early part of the 20th century, white Southerners

put forth the concept of Reconstruction as a tragic period, when Republicans motivated by revenge and profit used troops to force Southerners to accept corrupt governments run by unscrupulous Northerners and unqualified blacks. Such scholars generally dismissed the idea that blacks could ever be capable of governing. William Dunning, an influential historian at Columbia University

, believed that "black skin means membership in a race of men which has never of itself… created any civilization of any kind." The Dunning School's view of Reconstruction held sway for years. It was represented in D. W. Griffith

's popular movie The Birth of a Nation

(1915) and to some extent in Margaret Mitchell

's novel Gone with the Wind

(1934). More recent historians of the period have rejected many of the Dunning School's conclusions, and offer a different assessment.

Today's consensus regards Reconstruction as a time of idealism and hope, with some practical achievements. The Radical Republicans who passed the Fourteenth

and Fifteenth Amendments

were, for the most part, motivated by a desire to help freedmen

. African-American historian W. E. B. Du Bois put this view forward in 1910, and later historians Kenneth Stampp and Eric Foner

expanded it. The Republican Reconstruction governments had their share of corruption, but they benefited many whites, and were no more corrupt than Democratic

governments or, indeed, Northern Republican governments.

Furthermore, the Reconstruction governments established public education and social welfare institutions for the first time, improving education for both blacks and whites, and tried to improve social conditions for the many left in poverty after the long war. No Reconstruction state government was dominated by blacks; in fact, blacks did not attain a level of representation equal to their population in any state. When blacks did serve in public office, they often did so with distinction.

Many former Confederates

Many former Confederates

resisted Reconstruction with violence and intimidation. James Loewen

notes that between 1865 and 1867, when white Democrats controlled the government, whites murdered an average of one black person every day in Hinds County, Mississippi

. Black schools were an especially targeted; school buildings were frequently burned and teachers were flogged and occasionally murdered. This was the period when the secret vigilante group the Ku Klux Klan

(KKK) first arose, attacking freedmen and their white allies.

Nonetheless, blacks continued to vote and attend schools. Literacy soared, and many African-Americans were elected to local and statewide offices, with several serving in Congress. There were limits to Republican efforts on behalf of blacks; for example, a proposal of land reform

made by the Freedman's Bureau which would have granted blacks plots on the plantation land they worked never came to pass. However, for several years, the federal government, pushed by Northern opinion, showed itself willing to intervene to protect the rights of black Americans. The Force Acts and state action reduced the power of the KKK by the early 1870s. Because of the black community's commitment to education, the majority of blacks were literate by 1900.

Continued violence in the South, especially heated around electoral campaigns, sapped Northern intentions. More significantly, after the long years and losses of the Civil War, Northerners had lost heart for the massive commitment of money and arms that would have been required to stifle the white insurgency. The financial panic of 1873

Continued violence in the South, especially heated around electoral campaigns, sapped Northern intentions. More significantly, after the long years and losses of the Civil War, Northerners had lost heart for the massive commitment of money and arms that would have been required to stifle the white insurgency. The financial panic of 1873

disrupted the economy nationwide, causing more difficulties. The white insurgency took on new life ten years after the war. Conservative white Democrats waged an increasingly violent campaign, with the Colfax

and Coushatta Massacres

in Louisiana

in 1873 as signs. The next year saw the formation of paramilitary groups, such as the White League

in Louisiana (1874) and Red Shirts in Mississippi and the Carolinas, that worked openly to turn Republicans out of office, disrupt black organizing, and intimidate and suppress black voting. They invited press coverage. One historian described them as "the military arm of the Democratic Party." In 1874, in a continuation of the disputed gubernatorial election of 1872, thousands of White League militiamen fought against New Orleans police and Louisiana state militia and won. They turned out the Republican governor and installed the Democrat Samuel D. McEnery

, took over the capitol, state house and armory for a few days, and then retreated in the face of Federal troops. This was known as the "Battle of Liberty Place".

Northerners waffled and finally capitulated to the South, giving up on being able to control election violence. Abolitionist leaders like Horace Greeley

began to ally themselves with Democrats in attacking Reconstruction governments. By 1874 there was a Democratic majority in the House of Representatives. President Ulysses S. Grant

, who as a general had led the Union

to victory in the Civil War, initially refused to send troops to Mississippi in 1875 when the governor of the state asked him to. Violence surrounded the presidential election of 1876 in many areas, beginning a trend. After Grant, it would be many years before any President would do anything to extend the protection of the law to black people.

As noted above, white paramilitary forces contributed to whites' taking over power in the late 1870s. A brief coalition of populists took over in some states, but conservative Democrats had returned to power after the 1880s. From 1890 to 1908, they proceeded to pass legislation and constitutional amendments to disfranchise most blacks and many poor whites. They used a combination of restrictions on voter registration and voting methods, such as poll taxes, literacy and residency requirements, and ballot box changes. The main push came from elite Democrats in the Black Belt

As noted above, white paramilitary forces contributed to whites' taking over power in the late 1870s. A brief coalition of populists took over in some states, but conservative Democrats had returned to power after the 1880s. From 1890 to 1908, they proceeded to pass legislation and constitutional amendments to disfranchise most blacks and many poor whites. They used a combination of restrictions on voter registration and voting methods, such as poll taxes, literacy and residency requirements, and ballot box changes. The main push came from elite Democrats in the Black Belt

, where blacks were a majority of voters. The elite Democrats also acted to disfranchise poor whites. African Americans were an absolute majority of the population in Louisiana, Mississippi and South Carolina, and represented more than 40% of the population in four other former Confederate states. Accordingly, many whites perceived African Americans as a major political threat, because in free and fair elections, they would hold the balance of power in a majority of the South. South Carolina

Senator Ben Tillman proudly proclaimed in 1900, "We have done our level best [to prevent blacks from voting]...we have scratched our heads to find out how we could eliminate the last one of them. We stuffed ballot boxes. We shot them. We are not ashamed of it."

Conservative white Democratic governments passed Jim Crow

legislation, creating a system of legal racial segregation

in public and private facilities. Blacks were separated in schools and the few hospitals, were restricted in seating on trains, and had to use separate sections in some restaurants and public transportation systems. They were often barred from some stores, or forbidden to use lunchrooms, restrooms and fitting rooms. Because they could not vote, they could not serve on juries, which meant they had little if any legal recourse

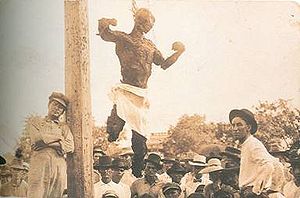

in the system. Indeed, between 1889 and 1922, as political disfranchisement and segregation were being established, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

(NAACP) calculates lynchings reached their worst level in history. Almost 3,500 people fell victim to lynching, almost all of them black men.

Historian James Loewen

notes that lynching emphasized the helplessness of blacks: "the defining characteristic of a lynching is that the murder takes place in public, so everyone knows who did it, yet the crime goes unpunished." Ostensibly prompted by black attacks or threats to white women, scholars and journalists have shown that lynchings arose out of economic competition and desire by competing whites for social control. African American civil rights activist Ida B. Wells-Barnett conducted one of the first systematic studies of the subject. She found blacks were "lynched for anything or nothing" – for wife-beating, stealing hogs, being "saucy to white people", sleeping with a consenting white woman – for being in the wrong place at the wrong time. It was a system of social terrorism.

Blacks who were economically successful faced reprisals or sanctions. When Richard Wright tried to train to become an optometrist and lens-grinder, the other men in the shop threatened him until he was forced to leave. In 1911 blacks were barred from participating in the Kentucky Derby

because African Americans won more than half of the first twenty-eight races. Through violence and legal restrictions, whites often prevented blacks from working as common laborers, much less as skilled artisans or in the professions. Under such conditions, even the most ambitious and talented black people found it extremely difficult to advance.

This situation called into question the views of Booker T. Washington

, the most prominent black leader during the early part of the nadir. He had argued that black people could better themselves by hard work and thrift. He believed they had to master basic work before going on to college careers and professional aspirations. Washington believed his programs trained blacks for the lives they were likely to lead and the jobs they could get in the South.

However, as W. E. B. Du Bois pointed out,

, 189 U.S. 475 (1903), which lost due to Supreme Court reluctance to interfere with states rights.

es virtually stampeded from Mississippi, Louisiana

, Alabama

, and Georgia

for the Midwest." More significantly, beginning about 1915, many blacks moved to Northern cities in what became known as the Great Migration

. Through the 1930s, more than 1.5 million blacks would leave the South for lives in the North, seeking work and the chance to escape lynchings and legal segregation. While they faced difficulties, overall they had better chances there. They had to make great cultural changes, as most went from rural areas to major industrial cities, and had to adjust from being rural workers to being urban workers. In the South, alarmed whites, worried that their labor force was leaving, often tried to block black migration.

During the nadir, Northern areas struggled with upheaval and hostility. In the Midwest and West, many towns posted "sundown" warnings

, threatening to kill African Americans who remained overnight. These were seldom the destinations of blacks seeking industrial jobs, however, so it was fear about something that was not going to happen. Monuments to Confederate War dead were erected across the nation – in Montana, for example. As an example, in its years of expansion, the Pennsylvania Railroad

recruited tens of thousands of workers from the South.

Black housing was often segregated in the North. There was competition for jobs and housing, as blacks entered cities which were also the destination of millions of immigrants from eastern

and southern Europe

. As more blacks moved north, they encountered racism where they had to battle over territory, often against ethnic Irish

, who were defending their power base. In some regions, blacks could not serve on juries. Blackface

shows, in which whites dressed as blacks portrayed African Americans as ignorant clowns, were popular in North and South. The Supreme Court reflected conservative tendencies and did not overrule southern constitutional changes resulting in disfranchisement. In 1896, the Court ruled in Plessy v. Ferguson

that "separate but equal" facilities for blacks were constitutional; the Court was made up almost entirely of Northerners.

While there were critics in the scientific community such as Franz Boas

, eugenics

and scientific racism

were promoted in academia by scientists Lothrop Stoddard

and Madison Grant

, who argued "scientific evidence" for the racial superiority of whites and thereby worked to justify racial segregation

and second-class citizenship for blacks.

Numerous blacks had voted for Democrat Woodrow Wilson

in the 1912 election, based on his promise to work for them. Instead, he introduced the re-segregation of government workplaces and employment in some agencies. Wilson was said to be a vocal fan of the film The Birth of a Nation

(1915), which celebrated the rise of the first Ku Klux Klan

. His praise was used to defend the film from the NAACP.

The Birth of a Nation helped popularize the second incarnation of the Ku Klux Klan

The Birth of a Nation helped popularize the second incarnation of the Ku Klux Klan

, which gained its greatest power and influence in the mid-1920s. In 1924, the Klan had four million members. (Current, p. 693). It also controlled the governorship and a majority of the state legislature in Indiana

, and exerted a powerful political influence in Arkansas

, Oklahoma

, California

, Georgia

, Oregon

, and Texas

. (Loewen, Lies Across America, pp. 161–162)

In the years during and after World War I

, there were great social tensions in the nation, not only because of the effects of the Great Migration and European immigration, but because of demobilization and the attempts of veterans to get jobs. Mass attacks on blacks that developed out of strikes and economic competition occurred in Houston, Philadelphia and in East St. Louis

in 1917.

In 1919 there were riots in several major cities, resulting in the Red Summer. The Chicago Race Riot of 1919

erupted into mob violence for several days. It left 15 whites and 23 blacks dead, over 500 injured and more than 1,000 homeless. An investigation found that ethnic Irish, who had established their own power base earlier on the South Side, were heavily implicated in the riots. The 1921 Tulsa Race Riot

in Tulsa, Oklahoma

was even more deadly; white mobs invaded and burned the Greenwood

district of Tulsa. 1,256 homes were destroyed and 39 people (26 black, 13 white) were confirmed killed, although recent investigations suggest that the number of black deaths could be considerably higher.

, and also developed new tactics that helped to spur the Civil Rights Movement

of the 1950s and 1960s. The Harlem Renaissance

and the popularity of jazz

music during the early part of the 20th century made many Americans more aware of black culture and more accepting of black celebrities.

Overall, however, the nadir was a disaster, certainly for black people and arguably for whites as well. Foner points out:

Similarly, Loewen argues that the family instability and crime which many sociologists have found in black communities can be traced, not to slavery, but to the nadir and its aftermath. (Lies My Teacher Told Me, p. 166)

Foner noted that "none of Reconstruction's black officials created a family political dynasty" and concluded rhat the nadir "aborted the development of the South's black political leadership." (p. 604)

Many commentators pointed out that lynchings and mob action

undermined respect for the established justice system. Lynching and mob violence continued in the first three decades of the twentieth century. More racial violence of whites against blacks arose in the South in relation to activities of the Civil Rights Movement

and Henry Arthur Callis, argued for dates as late as 1923. (Logan, p. xxi) Though the term "nadir" is still used to describe the post-Reconstruction and early 20th century period, the search for the single worst year has been abandoned.

History of the United States

The history of the United States traditionally starts with the Declaration of Independence in the year 1776, although its territory was inhabited by Native Americans since prehistoric times and then by European colonists who followed the voyages of Christopher Columbus starting in 1492. The...

from the end of Reconstruction through the early 20th century, when racism

Racism

Racism is the belief that inherent different traits in human racial groups justify discrimination. In the modern English language, the term "racism" is used predominantly as a pejorative epithet. It is applied especially to the practice or advocacy of racial discrimination of a pernicious nature...

in the country is deemed to have been worse than in any other period after the American Civil War

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

. During this period, African American

African American

African Americans are citizens or residents of the United States who have at least partial ancestry from any of the native populations of Sub-Saharan Africa and are the direct descendants of enslaved Africans within the boundaries of the present United States...

s lost many civil rights

Civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from unwarranted infringement by governments and private organizations, and ensure one's ability to participate in the civil and political life of the state without discrimination or repression.Civil rights include...

gains made during Reconstruction. Anti-black violence, lynching

Lynching

Lynching is an extrajudicial execution carried out by a mob, often by hanging, but also by burning at the stake or shooting, in order to punish an alleged transgressor, or to intimidate, control, or otherwise manipulate a population of people. It is related to other means of social control that...

s, segregation

Racial segregation

Racial segregation is the separation of humans into racial groups in daily life. It may apply to activities such as eating in a restaurant, drinking from a water fountain, using a public toilet, attending school, going to the movies, or in the rental or purchase of a home...

, legal racial discrimination

Discrimination

Discrimination is the prejudicial treatment of an individual based on their membership in a certain group or category. It involves the actual behaviors towards groups such as excluding or restricting members of one group from opportunities that are available to another group. The term began to be...

, and expressions of white supremacy

White supremacy

White supremacy is the belief, and promotion of the belief, that white people are superior to people of other racial backgrounds. The term is sometimes used specifically to describe a political ideology that advocates the social and political dominance by whites.White supremacy, as with racial...

increased.

Historian Rayford Logan

Rayford Logan

Rayford Whittingham Logan was an African-American historian and Pan-African activist. He was best known for his study of post-Reconstruction America, a period he termed "the nadir of American race relations"...

first used the phrase "the nadir" to describe this period in his 1954 book The Negro in American Life and Thought: The Nadir, 1877-1901. The phrase continues to be used, most notably in the books of James Loewen

James Loewen

James W. Loewen is a sociologist, historian, and author whose best-known work is Lies My Teacher Told Me: Everything Your American History Textbook Got Wrong .-Early life and career:...

, but also by other scholars. Loewen argued that the post-Reconstruction period was actually one of widespread hope for racial equity, when idealistic Northerners

Northern United States

Northern United States, also sometimes the North, may refer to:* A particular grouping of states or regions of the United States of America. The United States Census Bureau divides some of the northernmost United States into the Midwest Region and the Northeast Region...

championed civil rights. The true nadir, accordingly, began only when northern Republicans

Republican Party (United States)

The Republican Party is one of the two major contemporary political parties in the United States, along with the Democratic Party. Founded by anti-slavery expansion activists in 1854, it is often called the GOP . The party's platform generally reflects American conservatism in the U.S...

ceased supporting southern black rights around 1890, and extended through 1940. This period followed the financial Panic of 1873

Panic of 1873

The Panic of 1873 triggered a severe international economic depression in both Europe and the United States that lasted until 1879, and even longer in some countries. The depression was known as the Great Depression until the 1930s, but is now known as the Long Depression...

and a continuing decline in agriculture, and coincided with American imperialist aspirations, the Progressive Era

Progressive Era

The Progressive Era in the United States was a period of social activism and political reform that flourished from the 1890s to the 1920s. One main goal of the Progressive movement was purification of government, as Progressives tried to eliminate corruption by exposing and undercutting political...

, and the sundown town

Sundown town

A sundown town is a town that is or was purposely all-White. The term is widely used in the United States in areas from Ohio to Oregon and well into the South. The term came from signs that were allegedly posted stating that people of color had to leave the town by sundown...

phenomenon across the country.

Reconstruction

Southern United States

The Southern United States—commonly referred to as the American South, Dixie, or simply the South—constitutes a large distinctive area in the southeastern and south-central United States...

put forth the concept of Reconstruction as a tragic period, when Republicans motivated by revenge and profit used troops to force Southerners to accept corrupt governments run by unscrupulous Northerners and unqualified blacks. Such scholars generally dismissed the idea that blacks could ever be capable of governing. William Dunning, an influential historian at Columbia University

Columbia University

Columbia University in the City of New York is a private, Ivy League university in Manhattan, New York City. Columbia is the oldest institution of higher learning in the state of New York, the fifth oldest in the United States, and one of the country's nine Colonial Colleges founded before the...

, believed that "black skin means membership in a race of men which has never of itself… created any civilization of any kind." The Dunning School's view of Reconstruction held sway for years. It was represented in D. W. Griffith

D. W. Griffith

David Llewelyn Wark Griffith was a premier pioneering American film director. He is best known as the director of the controversial and groundbreaking 1915 film The Birth of a Nation and the subsequent film Intolerance .Griffith's film The Birth of a Nation made pioneering use of advanced camera...

's popular movie The Birth of a Nation

The Birth of a Nation

The Birth of a Nation is a 1915 American silent film directed by D. W. Griffith and based on the novel and play The Clansman, both by Thomas Dixon, Jr. Griffith also co-wrote the screenplay , and co-produced the film . It was released on February 8, 1915...

(1915) and to some extent in Margaret Mitchell

Margaret Mitchell

Margaret Munnerlyn Mitchell was an American author and journalist. Mitchell won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1937 for her epic American Civil War era novel, Gone with the Wind, which was the only novel by Mitchell published during her lifetime.-Family:Margaret Mitchell was born in Atlanta,...

's novel Gone with the Wind

Gone with the Wind

The slaves depicted in Gone with the Wind are primarily loyal house servants, such as Mammy, Pork and Uncle Peter, and these slaves stay on with their masters even after the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 sets them free...

(1934). More recent historians of the period have rejected many of the Dunning School's conclusions, and offer a different assessment.

Today's consensus regards Reconstruction as a time of idealism and hope, with some practical achievements. The Radical Republicans who passed the Fourteenth

Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution was adopted on July 9, 1868, as one of the Reconstruction Amendments.Its Citizenship Clause provides a broad definition of citizenship that overruled the Dred Scott v...

and Fifteenth Amendments

Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution prohibits each government in the United States from denying a citizen the right to vote based on that citizen's "race, color, or previous condition of servitude"...

were, for the most part, motivated by a desire to help freedmen

Freedman

A freedman is a former slave who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, slaves became freedmen either by manumission or emancipation ....

. African-American historian W. E. B. Du Bois put this view forward in 1910, and later historians Kenneth Stampp and Eric Foner

Eric Foner

Eric Foner is an American historian. On the faculty of the Department of History at Columbia University since 1982, he writes extensively on political history, the history of freedom, the early history of the Republican Party, African American biography, Reconstruction, and historiography...

expanded it. The Republican Reconstruction governments had their share of corruption, but they benefited many whites, and were no more corrupt than Democratic

Democratic Party (United States)

The Democratic Party is one of two major contemporary political parties in the United States, along with the Republican Party. The party's socially liberal and progressive platform is largely considered center-left in the U.S. political spectrum. The party has the lengthiest record of continuous...

governments or, indeed, Northern Republican governments.

Furthermore, the Reconstruction governments established public education and social welfare institutions for the first time, improving education for both blacks and whites, and tried to improve social conditions for the many left in poverty after the long war. No Reconstruction state government was dominated by blacks; in fact, blacks did not attain a level of representation equal to their population in any state. When blacks did serve in public office, they often did so with distinction.

Reconstruction's failure

Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America was a government set up from 1861 to 1865 by 11 Southern slave states of the United States of America that had declared their secession from the U.S...

resisted Reconstruction with violence and intimidation. James Loewen

James Loewen

James W. Loewen is a sociologist, historian, and author whose best-known work is Lies My Teacher Told Me: Everything Your American History Textbook Got Wrong .-Early life and career:...

notes that between 1865 and 1867, when white Democrats controlled the government, whites murdered an average of one black person every day in Hinds County, Mississippi

Hinds County, Mississippi

As of the census of 2000, there were 250,800 people, 91,030 households, and 62,355 families residing in the county. The population density was 288 people per square mile . There were 100,287 housing units at an average density of 115 per square mile...

. Black schools were an especially targeted; school buildings were frequently burned and teachers were flogged and occasionally murdered. This was the period when the secret vigilante group the Ku Klux Klan

Ku Klux Klan

Ku Klux Klan, often abbreviated KKK and informally known as the Klan, is the name of three distinct past and present far-right organizations in the United States, which have advocated extremist reactionary currents such as white supremacy, white nationalism, and anti-immigration, historically...

(KKK) first arose, attacking freedmen and their white allies.

Nonetheless, blacks continued to vote and attend schools. Literacy soared, and many African-Americans were elected to local and statewide offices, with several serving in Congress. There were limits to Republican efforts on behalf of blacks; for example, a proposal of land reform

Land reform

[Image:Jakarta farmers protest23.jpg|300px|thumb|right|Farmers protesting for Land Reform in Indonesia]Land reform involves the changing of laws, regulations or customs regarding land ownership. Land reform may consist of a government-initiated or government-backed property redistribution,...

made by the Freedman's Bureau which would have granted blacks plots on the plantation land they worked never came to pass. However, for several years, the federal government, pushed by Northern opinion, showed itself willing to intervene to protect the rights of black Americans. The Force Acts and state action reduced the power of the KKK by the early 1870s. Because of the black community's commitment to education, the majority of blacks were literate by 1900.

Panic of 1873

The Panic of 1873 triggered a severe international economic depression in both Europe and the United States that lasted until 1879, and even longer in some countries. The depression was known as the Great Depression until the 1930s, but is now known as the Long Depression...

disrupted the economy nationwide, causing more difficulties. The white insurgency took on new life ten years after the war. Conservative white Democrats waged an increasingly violent campaign, with the Colfax

Colfax massacre

The Colfax massacre or Colfax Riot occurred on Easter Sunday, April 13, 1873, in Colfax, Louisiana, the seat of Grant Parish, during Reconstruction, when white militia attacked freedmen at the Colfax courthouse...

and Coushatta Massacres

Coushatta massacre

The Coushatta Massacre was the result of an attack by the White League, a paramilitary organization composed of white Southern Democrats, on Republican officeholders and freedmen in Coushatta, the parish seat of Red River Parish, Louisiana...

in Louisiana

Louisiana

Louisiana is a state located in the southern region of the United States of America. Its capital is Baton Rouge and largest city is New Orleans. Louisiana is the only state in the U.S. with political subdivisions termed parishes, which are local governments equivalent to counties...

in 1873 as signs. The next year saw the formation of paramilitary groups, such as the White League

White League

The White League was a white paramilitary group started in 1874 that operated to turn Republicans out of office and intimidate freedmen from voting and political organizing. Its first chapter in Grant Parish, Louisiana was made up of many of the Confederate veterans who had participated in the...

in Louisiana (1874) and Red Shirts in Mississippi and the Carolinas, that worked openly to turn Republicans out of office, disrupt black organizing, and intimidate and suppress black voting. They invited press coverage. One historian described them as "the military arm of the Democratic Party." In 1874, in a continuation of the disputed gubernatorial election of 1872, thousands of White League militiamen fought against New Orleans police and Louisiana state militia and won. They turned out the Republican governor and installed the Democrat Samuel D. McEnery

Samuel D. McEnery

Samuel Douglas McEnery served as the 30th Governor of Louisiana from 1881 until 1888, and as a United States Senator from 1897 until 1910....

, took over the capitol, state house and armory for a few days, and then retreated in the face of Federal troops. This was known as the "Battle of Liberty Place".

Northerners waffled and finally capitulated to the South, giving up on being able to control election violence. Abolitionist leaders like Horace Greeley

Horace Greeley

Horace Greeley was an American newspaper editor, a founder of the Liberal Republican Party, a reformer, a politician, and an outspoken opponent of slavery...

began to ally themselves with Democrats in attacking Reconstruction governments. By 1874 there was a Democratic majority in the House of Representatives. President Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant was the 18th President of the United States as well as military commander during the Civil War and post-war Reconstruction periods. Under Grant's command, the Union Army defeated the Confederate military and ended the Confederate States of America...

, who as a general had led the Union

Union (American Civil War)

During the American Civil War, the Union was a name used to refer to the federal government of the United States, which was supported by the twenty free states and five border slave states. It was opposed by 11 southern slave states that had declared a secession to join together to form the...

to victory in the Civil War, initially refused to send troops to Mississippi in 1875 when the governor of the state asked him to. Violence surrounded the presidential election of 1876 in many areas, beginning a trend. After Grant, it would be many years before any President would do anything to extend the protection of the law to black people.

The South

Black Belt (U.S. region)

The Black Belt is a region of the Southern United States. Although the term originally described the prairies and dark soil of central Alabama and northeast Mississippi, it has long been used to describe a broad agricultural region in the American South characterized by a history of plantation...

, where blacks were a majority of voters. The elite Democrats also acted to disfranchise poor whites. African Americans were an absolute majority of the population in Louisiana, Mississippi and South Carolina, and represented more than 40% of the population in four other former Confederate states. Accordingly, many whites perceived African Americans as a major political threat, because in free and fair elections, they would hold the balance of power in a majority of the South. South Carolina

South Carolina

South Carolina is a state in the Deep South of the United States that borders Georgia to the south, North Carolina to the north, and the Atlantic Ocean to the east. Originally part of the Province of Carolina, the Province of South Carolina was one of the 13 colonies that declared independence...

Senator Ben Tillman proudly proclaimed in 1900, "We have done our level best [to prevent blacks from voting]...we have scratched our heads to find out how we could eliminate the last one of them. We stuffed ballot boxes. We shot them. We are not ashamed of it."

Conservative white Democratic governments passed Jim Crow

Jim Crow laws

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws in the United States enacted between 1876 and 1965. They mandated de jure racial segregation in all public facilities, with a supposedly "separate but equal" status for black Americans...

legislation, creating a system of legal racial segregation

Racial segregation in the United States

Racial segregation in the United States, as a general term, included the racial segregation or hypersegregation of facilities, services, and opportunities such as housing, medical care, education, employment, and transportation along racial lines...

in public and private facilities. Blacks were separated in schools and the few hospitals, were restricted in seating on trains, and had to use separate sections in some restaurants and public transportation systems. They were often barred from some stores, or forbidden to use lunchrooms, restrooms and fitting rooms. Because they could not vote, they could not serve on juries, which meant they had little if any legal recourse

Legal recourse

A legal recourse is an action that can be taken by an individual or a corporation to attempt to remedy a legal difficulty.* A lawsuit if the issue is a matter of civil law* Many contracts require mediation or arbitration before a dispute can go to court...

in the system. Indeed, between 1889 and 1922, as political disfranchisement and segregation were being established, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, usually abbreviated as NAACP, is an African-American civil rights organization in the United States, formed in 1909. Its mission is "to ensure the political, educational, social, and economic equality of rights of all persons and to...

(NAACP) calculates lynchings reached their worst level in history. Almost 3,500 people fell victim to lynching, almost all of them black men.

Historian James Loewen

James Loewen

James W. Loewen is a sociologist, historian, and author whose best-known work is Lies My Teacher Told Me: Everything Your American History Textbook Got Wrong .-Early life and career:...

notes that lynching emphasized the helplessness of blacks: "the defining characteristic of a lynching is that the murder takes place in public, so everyone knows who did it, yet the crime goes unpunished." Ostensibly prompted by black attacks or threats to white women, scholars and journalists have shown that lynchings arose out of economic competition and desire by competing whites for social control. African American civil rights activist Ida B. Wells-Barnett conducted one of the first systematic studies of the subject. She found blacks were "lynched for anything or nothing" – for wife-beating, stealing hogs, being "saucy to white people", sleeping with a consenting white woman – for being in the wrong place at the wrong time. It was a system of social terrorism.

Blacks who were economically successful faced reprisals or sanctions. When Richard Wright tried to train to become an optometrist and lens-grinder, the other men in the shop threatened him until he was forced to leave. In 1911 blacks were barred from participating in the Kentucky Derby

Kentucky Derby

The Kentucky Derby is a Grade I stakes race for three-year-old Thoroughbred horses, held annually in Louisville, Kentucky, United States on the first Saturday in May, capping the two-week-long Kentucky Derby Festival. The race is one and a quarter mile at Churchill Downs. Colts and geldings carry...

because African Americans won more than half of the first twenty-eight races. Through violence and legal restrictions, whites often prevented blacks from working as common laborers, much less as skilled artisans or in the professions. Under such conditions, even the most ambitious and talented black people found it extremely difficult to advance.

This situation called into question the views of Booker T. Washington

Booker T. Washington

Booker Taliaferro Washington was an American educator, author, orator, and political leader. He was the dominant figure in the African-American community in the United States from 1890 to 1915...

, the most prominent black leader during the early part of the nadir. He had argued that black people could better themselves by hard work and thrift. He believed they had to master basic work before going on to college careers and professional aspirations. Washington believed his programs trained blacks for the lives they were likely to lead and the jobs they could get in the South.

However, as W. E. B. Du Bois pointed out,

it is utterly impossible, under modern competitive methods, for working men and property-owners to defend their rights and exist without the right of suffrage.Washington had always (though often clandestinely) supported the right of black suffrage, and had fought against disfranchisement laws in Georgia, Louisiana, and other Southern states. This included secretive funding of litigation resulting in Giles v. Harris

Giles v. Harris

Giles v. Harris, 189 U.S. 475 , was an early 20th century United States Supreme Court case in which the Court upheld a state constitution's requirements for voter registration and qualifications...

, 189 U.S. 475 (1903), which lost due to Supreme Court reluctance to interfere with states rights.

United States as a whole

Many blacks voted with their feet and left the South to seek better conditions. In 1879, Logan notes, "some 40,000 NegroNegro

The word Negro is used in the English-speaking world to refer to a person of black ancestry or appearance, whether of African descent or not...

es virtually stampeded from Mississippi, Louisiana

Louisiana

Louisiana is a state located in the southern region of the United States of America. Its capital is Baton Rouge and largest city is New Orleans. Louisiana is the only state in the U.S. with political subdivisions termed parishes, which are local governments equivalent to counties...

, Alabama

Alabama

Alabama is a state located in the southeastern region of the United States. It is bordered by Tennessee to the north, Georgia to the east, Florida and the Gulf of Mexico to the south, and Mississippi to the west. Alabama ranks 30th in total land area and ranks second in the size of its inland...

, and Georgia

Georgia (U.S. state)

Georgia is a state located in the southeastern United States. It was established in 1732, the last of the original Thirteen Colonies. The state is named after King George II of Great Britain. Georgia was the fourth state to ratify the United States Constitution, on January 2, 1788...

for the Midwest." More significantly, beginning about 1915, many blacks moved to Northern cities in what became known as the Great Migration

Great Migration (African American)

The Great Migration was the movement of 6 million blacks out of the Southern United States to the Northeast, Midwest, and West from 1910 to 1970. Some historians differentiate between a Great Migration , numbering about 1.6 million migrants, and a Second Great Migration , in which 5 million or more...

. Through the 1930s, more than 1.5 million blacks would leave the South for lives in the North, seeking work and the chance to escape lynchings and legal segregation. While they faced difficulties, overall they had better chances there. They had to make great cultural changes, as most went from rural areas to major industrial cities, and had to adjust from being rural workers to being urban workers. In the South, alarmed whites, worried that their labor force was leaving, often tried to block black migration.

During the nadir, Northern areas struggled with upheaval and hostility. In the Midwest and West, many towns posted "sundown" warnings

Sundown town

A sundown town is a town that is or was purposely all-White. The term is widely used in the United States in areas from Ohio to Oregon and well into the South. The term came from signs that were allegedly posted stating that people of color had to leave the town by sundown...

, threatening to kill African Americans who remained overnight. These were seldom the destinations of blacks seeking industrial jobs, however, so it was fear about something that was not going to happen. Monuments to Confederate War dead were erected across the nation – in Montana, for example. As an example, in its years of expansion, the Pennsylvania Railroad

Pennsylvania Railroad

The Pennsylvania Railroad was an American Class I railroad, founded in 1846. Commonly referred to as the "Pennsy", the PRR was headquartered in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania....

recruited tens of thousands of workers from the South.

Black housing was often segregated in the North. There was competition for jobs and housing, as blacks entered cities which were also the destination of millions of immigrants from eastern

Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is the eastern part of Europe. The term has widely disparate geopolitical, geographical, cultural and socioeconomic readings, which makes it highly context-dependent and even volatile, and there are "almost as many definitions of Eastern Europe as there are scholars of the region"...

and southern Europe

Southern Europe

The term Southern Europe, at its most general definition, is used to mean "all countries in the south of Europe". However, the concept, at different times, has had different meanings, providing additional political, linguistic and cultural context to the definition in addition to the typical...

. As more blacks moved north, they encountered racism where they had to battle over territory, often against ethnic Irish

Irish American

Irish Americans are citizens of the United States who can trace their ancestry to Ireland. A total of 36,278,332 Americans—estimated at 11.9% of the total population—reported Irish ancestry in the 2008 American Community Survey conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau...

, who were defending their power base. In some regions, blacks could not serve on juries. Blackface

Blackface

Blackface is a form of theatrical makeup used in minstrel shows, and later vaudeville, in which performers create a stereotyped caricature of a black person. The practice gained popularity during the 19th century and contributed to the proliferation of stereotypes such as the "happy-go-lucky darky...

shows, in which whites dressed as blacks portrayed African Americans as ignorant clowns, were popular in North and South. The Supreme Court reflected conservative tendencies and did not overrule southern constitutional changes resulting in disfranchisement. In 1896, the Court ruled in Plessy v. Ferguson

Plessy v. Ferguson

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 , is a landmark United States Supreme Court decision in the jurisprudence of the United States, upholding the constitutionality of state laws requiring racial segregation in private businesses , under the doctrine of "separate but equal".The decision was handed...

that "separate but equal" facilities for blacks were constitutional; the Court was made up almost entirely of Northerners.

While there were critics in the scientific community such as Franz Boas

Franz Boas

Franz Boas was a German-American anthropologist and a pioneer of modern anthropology who has been called the "Father of American Anthropology" and "the Father of Modern Anthropology." Like many such pioneers, he trained in other disciplines; he received his doctorate in physics, and did...

, eugenics

Eugenics

Eugenics is the "applied science or the bio-social movement which advocates the use of practices aimed at improving the genetic composition of a population", usually referring to human populations. The origins of the concept of eugenics began with certain interpretations of Mendelian inheritance,...

and scientific racism

Scientific racism

Scientific racism is the use of scientific techniques and hypotheses to sanction the belief in racial superiority or racism.This is not the same as using scientific findings and the scientific method to investigate differences among the humans and argue that there are races...

were promoted in academia by scientists Lothrop Stoddard

Lothrop Stoddard

Theodore Lothrop Stoddard was an American historian, journalist, racial anthropologist, eugenicist, political theorist and anti-immigration advocate who wrote a number of books which are cited by historians as prominent examples of early 20th-century scientific racism.- Biography :Stoddard was...

and Madison Grant

Madison Grant

Madison Grant was an American lawyer, historian and physical anthropologist, known primarily for his work as a eugenicist and conservationist...

, who argued "scientific evidence" for the racial superiority of whites and thereby worked to justify racial segregation

Racial segregation

Racial segregation is the separation of humans into racial groups in daily life. It may apply to activities such as eating in a restaurant, drinking from a water fountain, using a public toilet, attending school, going to the movies, or in the rental or purchase of a home...

and second-class citizenship for blacks.

Numerous blacks had voted for Democrat Woodrow Wilson

Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson was the 28th President of the United States, from 1913 to 1921. A leader of the Progressive Movement, he served as President of Princeton University from 1902 to 1910, and then as the Governor of New Jersey from 1911 to 1913...

in the 1912 election, based on his promise to work for them. Instead, he introduced the re-segregation of government workplaces and employment in some agencies. Wilson was said to be a vocal fan of the film The Birth of a Nation

The Birth of a Nation

The Birth of a Nation is a 1915 American silent film directed by D. W. Griffith and based on the novel and play The Clansman, both by Thomas Dixon, Jr. Griffith also co-wrote the screenplay , and co-produced the film . It was released on February 8, 1915...

(1915), which celebrated the rise of the first Ku Klux Klan

Ku Klux Klan

Ku Klux Klan, often abbreviated KKK and informally known as the Klan, is the name of three distinct past and present far-right organizations in the United States, which have advocated extremist reactionary currents such as white supremacy, white nationalism, and anti-immigration, historically...

. His praise was used to defend the film from the NAACP.

Ku Klux Klan

Ku Klux Klan, often abbreviated KKK and informally known as the Klan, is the name of three distinct past and present far-right organizations in the United States, which have advocated extremist reactionary currents such as white supremacy, white nationalism, and anti-immigration, historically...

, which gained its greatest power and influence in the mid-1920s. In 1924, the Klan had four million members. (Current, p. 693). It also controlled the governorship and a majority of the state legislature in Indiana

Indiana

Indiana is a US state, admitted to the United States as the 19th on December 11, 1816. It is located in the Midwestern United States and Great Lakes Region. With 6,483,802 residents, the state is ranked 15th in population and 16th in population density. Indiana is ranked 38th in land area and is...

, and exerted a powerful political influence in Arkansas

Arkansas

Arkansas is a state located in the southern region of the United States. Its name is an Algonquian name of the Quapaw Indians. Arkansas shares borders with six states , and its eastern border is largely defined by the Mississippi River...

, Oklahoma

Oklahoma

Oklahoma is a state located in the South Central region of the United States of America. With an estimated 3,751,351 residents as of the 2010 census and a land area of 68,667 square miles , Oklahoma is the 28th most populous and 20th-largest state...

, California

California

California is a state located on the West Coast of the United States. It is by far the most populous U.S. state, and the third-largest by land area...

, Georgia

Georgia (U.S. state)

Georgia is a state located in the southeastern United States. It was established in 1732, the last of the original Thirteen Colonies. The state is named after King George II of Great Britain. Georgia was the fourth state to ratify the United States Constitution, on January 2, 1788...

, Oregon

Oregon

Oregon is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. It is located on the Pacific coast, with Washington to the north, California to the south, Nevada on the southeast and Idaho to the east. The Columbia and Snake rivers delineate much of Oregon's northern and eastern...

, and Texas

Texas

Texas is the second largest U.S. state by both area and population, and the largest state by area in the contiguous United States.The name, based on the Caddo word "Tejas" meaning "friends" or "allies", was applied by the Spanish to the Caddo themselves and to the region of their settlement in...

. (Loewen, Lies Across America, pp. 161–162)

In the years during and after World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

, there were great social tensions in the nation, not only because of the effects of the Great Migration and European immigration, but because of demobilization and the attempts of veterans to get jobs. Mass attacks on blacks that developed out of strikes and economic competition occurred in Houston, Philadelphia and in East St. Louis

East St. Louis Riot

The East St. Louis Riot was an outbreak of labor- and race-related violence that caused between 40 and 200 deaths and extensive property damage. East St. Louis, Illinois, is an industrial city on the east bank of the Mississippi River across from St. Louis, Missouri...

in 1917.

In 1919 there were riots in several major cities, resulting in the Red Summer. The Chicago Race Riot of 1919

Chicago Race Riot of 1919

The Chicago Race Riot of 1919 was a major racial conflict that began in Chicago, Illinois on July 27, 1919 and ended on August 3. During the riot, dozens died and hundreds were injured. It is considered the worst of the approximately 25 riots during the Red Summer of 1919, so named because of the...

erupted into mob violence for several days. It left 15 whites and 23 blacks dead, over 500 injured and more than 1,000 homeless. An investigation found that ethnic Irish, who had established their own power base earlier on the South Side, were heavily implicated in the riots. The 1921 Tulsa Race Riot

Tulsa Race Riot

The Tulsa race riot was a large-scale racially motivated conflict, May 31 - June 1st 1921, between the white and black communities of Tulsa, Oklahoma, in which the wealthiest African-American community in the United States, the Greenwood District also known as 'The Negro Wall St' was burned to the...

in Tulsa, Oklahoma

Tulsa, Oklahoma

Tulsa is the second-largest city in the state of Oklahoma and 46th-largest city in the United States. With a population of 391,906 as of the 2010 census, it is the principal municipality of the Tulsa Metropolitan Area, a region with 937,478 residents in the MSA and 988,454 in the CSA. Tulsa's...

was even more deadly; white mobs invaded and burned the Greenwood

Greenwood, Tulsa, Oklahoma

Greenwood was a district in Tulsa, Oklahoma. As one of the most successful and wealthiest African American communities in the United States during the early 20th Century, it was popularly known as America's "Black Wall Street" until the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921...

district of Tulsa. 1,256 homes were destroyed and 39 people (26 black, 13 white) were confirmed killed, although recent investigations suggest that the number of black deaths could be considerably higher.

Legacy

Black literacy levels, which rose during Reconstruction, continued to increase through this period. The NAACP was established in 1909, and by 1920 the group won a few important anti-discrimination lawsuits. African Americans, such as Du Bois and Wells-Barnett, continued the tradition of advocacy, organizing, and journalism which helped spur abolitionismAbolitionism

Abolitionism is a movement to end slavery.In western Europe and the Americas abolitionism was a movement to end the slave trade and set slaves free. At the behest of Dominican priest Bartolomé de las Casas who was shocked at the treatment of natives in the New World, Spain enacted the first...

, and also developed new tactics that helped to spur the Civil Rights Movement

African-American Civil Rights Movement (1955-1968)

The African-American Civil Rights Movement refers to the movements in the United States aimed at outlawing racial discrimination against African Americans and restoring voting rights to them. This article covers the phase of the movement between 1955 and 1968, particularly in the South...

of the 1950s and 1960s. The Harlem Renaissance

Harlem Renaissance

The Harlem Renaissance was a cultural movement that spanned the 1920s and 1930s. At the time, it was known as the "New Negro Movement", named after the 1925 anthology by Alain Locke...

and the popularity of jazz

Jazz

Jazz is a musical style that originated at the beginning of the 20th century in African American communities in the Southern United States. It was born out of a mix of African and European music traditions. From its early development until the present, jazz has incorporated music from 19th and 20th...

music during the early part of the 20th century made many Americans more aware of black culture and more accepting of black celebrities.

Overall, however, the nadir was a disaster, certainly for black people and arguably for whites as well. Foner points out:

...by the early twentieth century [racism] had become more deeply embedded in the nation's culture and politics than at any time since the beginning of the antislavery crusade and perhaps in our nation's entire history.

Similarly, Loewen argues that the family instability and crime which many sociologists have found in black communities can be traced, not to slavery, but to the nadir and its aftermath. (Lies My Teacher Told Me, p. 166)

Foner noted that "none of Reconstruction's black officials created a family political dynasty" and concluded rhat the nadir "aborted the development of the South's black political leadership." (p. 604)

Many commentators pointed out that lynchings and mob action

Mob Action

Mob Action is a clothing label based in Leipzig, Germany. The name is synonymous with riot, outlining the company's political appeal....

undermined respect for the established justice system. Lynching and mob violence continued in the first three decades of the twentieth century. More racial violence of whites against blacks arose in the South in relation to activities of the Civil Rights Movement

Exact year

Logan took some trouble to establish the exact year when the nadir reached its lowest point; he argued for 1901, suggesting that relations improved after then. Others, such as John Hope FranklinJohn Hope Franklin

John Hope Franklin was a United States historian and past president of Phi Beta Kappa, the Organization of American Historians, the American Historical Association, and the Southern Historical Association. Franklin is best known for his work From Slavery to Freedom, first published in 1947, and...

and Henry Arthur Callis, argued for dates as late as 1923. (Logan, p. xxi) Though the term "nadir" is still used to describe the post-Reconstruction and early 20th century period, the search for the single worst year has been abandoned.

See also

- White SupremacyWhite supremacyWhite supremacy is the belief, and promotion of the belief, that white people are superior to people of other racial backgrounds. The term is sometimes used specifically to describe a political ideology that advocates the social and political dominance by whites.White supremacy, as with racial...

- Anti-racismAnti-racismAnti-racism includes beliefs, actions, movements, and policies adopted or developed to oppose racism. In general, anti-racism is intended to promote an egalitarian society in which people do not face discrimination on the basis of their race, however defined...