James Smithson

Encyclopedia

- For related terms, see Smithsonian (disambiguation)Smithsonian (disambiguation)Smithsonian can refer to:* the Smithsonian Institution, a museum in Washington, D.C.** the Smithsonian Institution Building** Smithsonian , a magazine published by the Institution...

.

James Smithson, FRS, M.A. (c.1764 – 27 June 1829) was a British

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

mineralogist and chemist

Chemist

A chemist is a scientist trained in the study of chemistry. Chemists study the composition of matter and its properties such as density and acidity. Chemists carefully describe the properties they study in terms of quantities, with detail on the level of molecules and their component atoms...

noted for having left a bequest

Bequest

A bequest is the act of giving property by will. Strictly, "bequest" is used of personal property, and "devise" of real property. In legal terminology, "bequeath" is a verb form meaning "to make a bequest."...

in his will to the United States of America

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

, to create "an establishment for the increase and diffusion of knowledge among men" to be called the Smithsonian Institution

Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution is an educational and research institute and associated museum complex, administered and funded by the government of the United States and by funds from its endowment, contributions, and profits from its retail operations, concessions, licensing activities, and magazines...

.

Biography

Not much is known about Smithson's life: his scientific collections, notebooks, diaries, and correspondence were lost in a fire that destroyed much of the Smithsonian Institution BuildingSmithsonian Institution Building

The Smithsonian Castle, located on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. behind the National Museum of African Art, houses the Smithsonian Institution's administrative offices and information center...

in 1865; only the 213 volumes of his personal library and some personal writings survived. Smithson was born Jacques Louis Macie on an unknown date in 1764 or 1765, in Paris

Paris

Paris is the capital and largest city in France, situated on the river Seine, in northern France, at the heart of the Île-de-France region...

, France

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

, an illegitimate, unacknowledged son of one of Britain's most prominent landowners, the highly regarded and accomplished Sir Hugh Smithson, 4th Baronet

Baronet

A baronet or the rare female equivalent, a baronetess , is the holder of a hereditary baronetcy awarded by the British Crown...

of Stanwick

Stanwick St John

Stanwick St John is a village and civil parish in the Richmondshire district of North Yorkshire, England. It is situated between the towns of Darlington and Richmond, close to Scotch Corner and the remains of the Roman fort and bridge at Piercebridge....

, north Yorkshire

Yorkshire

Yorkshire is a historic county of northern England and the largest in the United Kingdom. Because of its great size in comparison to other English counties, functions have been increasingly undertaken over time by its subdivisions, which have also been subject to periodic reform...

, who had married into the Percy family and who in 1766 became 1st Duke of Northumberland

Hugh Percy, 1st Duke of Northumberland

Hugh Percy, 1st Duke of Northumberland, KG, PC was an Engish peer, landowner and art patron.He was born Hugh Smithson, the son of Langdale Smithson and grandson of Sir Hugh Smithson, 3rd Baronet from whom he inherited the baronetcy in 1733...

, K.G.

Elizabeth Percy, Duchess of Northumberland

Elizabeth Percy, née Seymour, Duchess of Northumberland, heiress to the earldom of Northumberland and 2nd Baroness Percy was a British peeress....

, and an heiress in her own right, to the property of the Hungerfords of Studley

Studley

Studley is a large village and civil parish in the Stratford-on-Avon district of Warwickshire, England. Situated on the western edge of Warwickshire near the border with Worcestershire it is southeast of Redditch and northwest of Stratford. The Roman road of Ryknild Street, now the A435, passes...

. She was also the widow of John Macie, of Weston, near Bath, Somerset

Somerset

The ceremonial and non-metropolitan county of Somerset in South West England borders Bristol and Gloucestershire to the north, Wiltshire to the east, Dorset to the south-east, and Devon to the south-west. It is partly bounded to the north and west by the Bristol Channel and the estuary of the...

; so the young Smithson originally was called Jacques Louis Macie. His mother later married John Marshe Dickinson, a troubled son of Marshe Dickinson who was Lord Mayor of the City of London in 1757 and Member of Parliament

Member of Parliament

A Member of Parliament is a representative of the voters to a :parliament. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, the term applies specifically to members of the lower house, as upper houses often have a different title, such as senate, and thus also have different titles for its members,...

. During this marriage, she had another son, called Henry Louis Dickenson; but the 1st Duke of Northumberland, rather than Dickinson, is thought to have been the father of this second son also.

Smithson commenced undergraduate studies at Pembroke College

Pembroke College, Oxford

Pembroke College is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in England, located in Pembroke Square. As of 2009, Pembroke had an estimated financial endowment of £44.9 million.-History:...

, University of Oxford

University of Oxford

The University of Oxford is a university located in Oxford, United Kingdom. It is the second-oldest surviving university in the world and the oldest in the English-speaking world. Although its exact date of foundation is unclear, there is evidence of teaching as far back as 1096...

, in 1782 and received a Master of Arts (M.A.) degree in 1786 (he matriculated as Jacobus Ludovicus Macie). French geologist

Geologist

A geologist is a scientist who studies the solid and liquid matter that constitutes the Earth as well as the processes and history that has shaped it. Geologists usually engage in studying geology. Geologists, studying more of an applied science than a theoretical one, must approach Geology using...

Barthélemy Faujas de Saint-Fond

Barthélemy Faujas de Saint-Fond

Barthélemy Faujas de Saint-Fond , French geologist and traveller, was born at Montélimar. He was educated at the Jesuit's College at Lyon; afterwards he went to Grenoble where he studied law and was admitted as an advocate to the parlement.He rose to be president of the seneschal's court in...

, who traveled with the young man on a geological tour of Scotland in 1784, described him as "a studious young man, who was much attached to mineralogy." (The other members of the tour were William Thornton

William Thornton

Dr. William Thornton was a British-American physician, inventor, painter and architect who designed the United States Capitol, an authentic polymath...

and the Italian count Paolo Andreani.)

On 19 April 1787, at age 22, under the name James Lewis Macie, he was elected the then youngest fellow of the Royal Society

Royal Society

The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, known simply as the Royal Society, is a learned society for science, and is possibly the oldest such society in existence. Founded in November 1660, it was granted a Royal Charter by King Charles II as the "Royal Society of London"...

. His sponsors for membership were Henry Cavendish

Henry Cavendish

Henry Cavendish FRS was a British scientist noted for his discovery of hydrogen or what he called "inflammable air". He described the density of inflammable air, which formed water on combustion, in a 1766 paper "On Factitious Airs". Antoine Lavoisier later reproduced Cavendish's experiment and...

, Richard Kirwan

Richard Kirwan

Richard Kirwan FRS was an Irish scientist. He is remembered today, if at all, for being one of the last supporters of the theory of phlogiston. Kirwan was active in the fields of chemistry, meteorology, and geology...

, Charles Greville

Charles Francis Greville

Charles Francis Greville PC, FRS , was a British antiquarian, collector and politician.-Background:Greville was the second son of Francis Greville, 1st Earl of Warwick, by Elizabeth Hamilton, daughter of Lord Archibald Hamilton...

, and the Society's secretary, Charles Blagden

Charles Blagden

Sir Charles Brian Blagden FRS was a British physician and scientist. He served as a medical officer in the Army and later held the position of Secretary of the Royal Society...

. Smithson was also related to another member, the poet, collector, gadfly, and friend of Voltaire

Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet , better known by the pen name Voltaire , was a French Enlightenment writer, historian and philosopher famous for his wit and for his advocacy of civil liberties, including freedom of religion, free trade and separation of church and state...

, George Keate (1729–1797), who had become F.R.S. in 1766.

When his mother died, in 1800, he immediately began the process to change his surname from Macie to his father's surname, Smithson, which was officially recognized by Act of Parliament in 1801.

Smithson died on 27 June 1829, in Genoa

Genoa

Genoa |Ligurian]] Zena ; Latin and, archaically, English Genua) is a city and an important seaport in northern Italy, the capital of the Province of Genoa and of the region of Liguria....

; his body was buried in the English cemetery of San Benigno there. In 1904, Alexander Graham Bell

Alexander Graham Bell

Alexander Graham Bell was an eminent scientist, inventor, engineer and innovator who is credited with inventing the first practical telephone....

, then Regent of the Smithsonian Institution, brought Smithson's remains from Genoa to Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly referred to as Washington, "the District", or simply D.C., is the capital of the United States. On July 16, 1790, the United States Congress approved the creation of a permanent national capital as permitted by the U.S. Constitution....

, where they were entombed at the Smithsonian Institution Building (The Castle). His sarcophagus incorrectly states his age at his death as 75; he was around 65.

The Smithsonian Institution archives has amassed some materials related to him.

Scientific career

Florence

Florence is the capital city of the Italian region of Tuscany and of the province of Florence. It is the most populous city in Tuscany, with approximately 370,000 inhabitants, expanding to over 1.5 million in the metropolitan area....

, Paris, Saxony

Saxony

The Free State of Saxony is a landlocked state of Germany, contingent with Brandenburg, Saxony Anhalt, Thuringia, Bavaria, the Czech Republic and Poland. It is the tenth-largest German state in area, with of Germany's sixteen states....

, the Swiss Alps

Swiss Alps

The Swiss Alps are the portion of the Alps mountain range that lies within Switzerland. Because of their central position within the entire Alpine range, they are also known as the Central Alps....

, and many other parts of Europe to find crystal

Crystal

A crystal or crystalline solid is a solid material whose constituent atoms, molecules, or ions are arranged in an orderly repeating pattern extending in all three spatial dimensions. The scientific study of crystals and crystal formation is known as crystallography...

s and mineral

Mineral

A mineral is a naturally occurring solid chemical substance formed through biogeochemical processes, having characteristic chemical composition, highly ordered atomic structure, and specific physical properties. By comparison, a rock is an aggregate of minerals and/or mineraloids and does not...

s on which he could perform experiment

Experiment

An experiment is a methodical procedure carried out with the goal of verifying, falsifying, or establishing the validity of a hypothesis. Experiments vary greatly in their goal and scale, but always rely on repeatable procedure and logical analysis of the results...

s – including diluting, grinding, igniting, and even chewing and sniffing them – to discover and classify their elemental

Chemical element

A chemical element is a pure chemical substance consisting of one type of atom distinguished by its atomic number, which is the number of protons in its nucleus. Familiar examples of elements include carbon, oxygen, aluminum, iron, copper, gold, mercury, and lead.As of November 2011, 118 elements...

properties. In 1802, Smithson proved that zinc carbonates were true carbonate

Carbonate

In chemistry, a carbonate is a salt of carbonic acid, characterized by the presence of the carbonate ion, . The name may also mean an ester of carbonic acid, an organic compound containing the carbonate group C2....

minerals and not zinc oxide

Zinc oxide

Zinc oxide is an inorganic compound with the formula ZnO. It is a white powder that is insoluble in water. The powder is widely used as an additive into numerous materials and products including plastics, ceramics, glass, cement, rubber , lubricants, paints, ointments, adhesives, sealants,...

s, as was previously thought. One, zinc spar (ZnC

Carbon

Carbon is the chemical element with symbol C and atomic number 6. As a member of group 14 on the periodic table, it is nonmetallic and tetravalent—making four electrons available to form covalent chemical bonds...

O

Oxygen

Oxygen is the element with atomic number 8 and represented by the symbol O. Its name derives from the Greek roots ὀξύς and -γενής , because at the time of naming, it was mistakenly thought that all acids required oxygen in their composition...

3), a type of zinc

Zinc

Zinc , or spelter , is a metallic chemical element; it has the symbol Zn and atomic number 30. It is the first element in group 12 of the periodic table. Zinc is, in some respects, chemically similar to magnesium, because its ion is of similar size and its only common oxidation state is +2...

ore, was renamed smithsonite

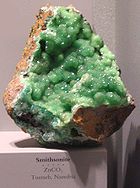

Smithsonite

Smithsonite, or zinc spar, is zinc carbonate , a mineral ore of zinc. Historically, smithsonite was identified with hemimorphite before it was realised that they were two distinct minerals. The two minerals are very similar in appearance and the term calamine has been used for both, leading to some...

posthumously in Smithson's honour in 1832 by the noted French scientist François Sulpice Beudant

François Sulpice Beudant

François Sulpice Beudant , French mineralogist and geologist, was born in Paris.He was educated at the Ecole Polytechnique and Ecole Normale, and in 1811 was appointed professor of mathematics at the lycée of Avignon. Thence he was called, in 1813, to the lycée of Marseilles to fill the post of...

. Smithsonite was a principal source of zinc

Zinc

Zinc , or spelter , is a metallic chemical element; it has the symbol Zn and atomic number 30. It is the first element in group 12 of the periodic table. Zinc is, in some respects, chemically similar to magnesium, because its ion is of similar size and its only common oxidation state is +2...

until the 1880s. Smithson also invented the term silicate

Silicate

A silicate is a compound containing a silicon bearing anion. The great majority of silicates are oxides, but hexafluorosilicate and other anions are also included. This article focuses mainly on the Si-O anions. Silicates comprise the majority of the earth's crust, as well as the other...

.

Wherever he went, Smithson made minute observations on the climate, physical features, and geological structure of the locality visited, the characteristics of its minerals, the methods employed in mining or smelting ores, and in all kinds of manufactures. Desirous of bringing to the practical test of actual experiment everything that came to his notice, he fitted up and carried with him a portable laboratory. He collected also a cabinet of minerals, composed of thousands of minute specimens, including all the rarest gems, so that immediate comparison could be made of a novel or undetermined specimen with an accurately arranged and labelled collection.

His first paper, presented to the Royal Society in 1791, was “An Account of some Chemical Experiments on Tabasheer

Tabasheer

Tabasheer or Banslochan is a translucent white substance, composed mainly of silica and water with traces of lime and potash, obtained from the nodal joints of some species of bamboo. It is part of the pharmacology of the traditional Ayurvedic and Unani systems of medicine of the Indian...

,” and was followed from that time until 1817 with eight other memoirs treating for the most part of chemical analyses of various substances, principally minerals. Smithson published at least 27 papers on chemistry

Chemistry

Chemistry is the science of matter, especially its chemical reactions, but also its composition, structure and properties. Chemistry is concerned with atoms and their interactions with other atoms, and particularly with the properties of chemical bonds....

, geology

Geology

Geology is the science comprising the study of solid Earth, the rocks of which it is composed, and the processes by which it evolves. Geology gives insight into the history of the Earth, as it provides the primary evidence for plate tectonics, the evolutionary history of life, and past climates...

, and mineralogy in scientific journals. His topics included the chemical content of a lady's teardrop

Tears

Tears are secretions that clean and lubricate the eyes. Lacrimation or lachrymation is the production or shedding of tears....

, the crystalline form of ice

Ice

Ice is water frozen into the solid state. Usually ice is the phase known as ice Ih, which is the most abundant of the varying solid phases on the Earth's surface. It can appear transparent or opaque bluish-white color, depending on the presence of impurities or air inclusions...

, and an improved method of making coffee

Coffee

Coffee is a brewed beverage with a dark,init brooo acidic flavor prepared from the roasted seeds of the coffee plant, colloquially called coffee beans. The beans are found in coffee cherries, which grow on trees cultivated in over 70 countries, primarily in equatorial Latin America, Southeast Asia,...

. He was acquainted with leading scientists of his day, including French mathematician

Mathematician

A mathematician is a person whose primary area of study is the field of mathematics. Mathematicians are concerned with quantity, structure, space, and change....

, physicist

Physicist

A physicist is a scientist who studies or practices physics. Physicists study a wide range of physical phenomena in many branches of physics spanning all length scales: from sub-atomic particles of which all ordinary matter is made to the behavior of the material Universe as a whole...

and astronomer

Astronomer

An astronomer is a scientist who studies celestial bodies such as planets, stars and galaxies.Historically, astronomy was more concerned with the classification and description of phenomena in the sky, while astrophysics attempted to explain these phenomena and the differences between them using...

François Arago

François Arago

François Jean Dominique Arago , known simply as François Arago , was a French mathematician, physicist, astronomer and politician.-Early life and work:...

; Sir Joseph Banks

Joseph Banks

Sir Joseph Banks, 1st Baronet, GCB, PRS was an English naturalist, botanist and patron of the natural sciences. He took part in Captain James Cook's first great voyage . Banks is credited with the introduction to the Western world of eucalyptus, acacia, mimosa and the genus named after him,...

; Henry Cavendish

Henry Cavendish

Henry Cavendish FRS was a British scientist noted for his discovery of hydrogen or what he called "inflammable air". He described the density of inflammable air, which formed water on combustion, in a 1766 paper "On Factitious Airs". Antoine Lavoisier later reproduced Cavendish's experiment and...

; Scottish

Scotland

Scotland is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Occupying the northern third of the island of Great Britain, it shares a border with England to the south and is bounded by the North Sea to the east, the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, and the North Channel and Irish Sea to the...

geologist

Geologist

A geologist is a scientist who studies the solid and liquid matter that constitutes the Earth as well as the processes and history that has shaped it. Geologists usually engage in studying geology. Geologists, studying more of an applied science than a theoretical one, must approach Geology using...

James Hutton

James Hutton

James Hutton was a Scottish physician, geologist, naturalist, chemical manufacturer and experimental agriculturalist. He is considered the father of modern geology...

; Irish

Ireland

Ireland is an island to the northwest of continental Europe. It is the third-largest island in Europe and the twentieth-largest island on Earth...

chemist

Chemist

A chemist is a scientist trained in the study of chemistry. Chemists study the composition of matter and its properties such as density and acidity. Chemists carefully describe the properties they study in terms of quantities, with detail on the level of molecules and their component atoms...

Richard Kirwan

Richard Kirwan

Richard Kirwan FRS was an Irish scientist. He is remembered today, if at all, for being one of the last supporters of the theory of phlogiston. Kirwan was active in the fields of chemistry, meteorology, and geology...

; Antoine Lavoisier

Antoine Lavoisier

Antoine-Laurent de Lavoisier , the "father of modern chemistry", was a French nobleman prominent in the histories of chemistry and biology...

and Joseph Priestley

Joseph Priestley

Joseph Priestley, FRS was an 18th-century English theologian, Dissenting clergyman, natural philosopher, chemist, educator, and political theorist who published over 150 works...

.

The Smithsonian connection

The nephew, Henry Hungerford (the soi disant Baron Enrico de la Batut), died without heirs in 1835, and Smithson's bequest was accepted in 1836 by the United States Congress

United States Congress

The United States Congress is the bicameral legislature of the federal government of the United States, consisting of the Senate and the House of Representatives. The Congress meets in the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C....

. A lawsuit (in Britain) contesting the will was decided in favour of the U.S. in 1838 and 11 boxes containing 104,960 gold sovereign

British Sovereign coin

The sovereign is a gold coin of the United Kingdom, with a nominal value of one pound sterling but in practice used as a bullion coin.Named after the English gold sovereign, last minted in 1604, the name was revived with the Great Recoinage of 1816. Minting these new sovereigns began in 1817...

s were shipped to Philadelphia and minted into dollar

Dollar

The dollar is the name of the official currency of many countries, including Australia, Belize, Canada, Ecuador, El Salvador, Hong Kong, New Zealand, Singapore, Taiwan, and the United States.-Etymology:...

coinage worth $508,318. There was a good deal of controversy about how the purposes of the bequest could be fulfilled, and it was not until 1846 that the Smithsonian Institution was founded by Act of Congress.

Smithson had never been to the United States, and the motive for the specific bequest is unknown. In 1857 (before the destruction of Smithson's diaries), the Smithsonian published an article that stated, "He [James Smithson] declared, in writing, that though the best blood of England flowed in his veins, this availed him not, for his name would live in the memory of men when the titles of Northumberlands and Percies were extinct or forgotten." If anyone perused Smithson's papers prior to the 1865 fire looking for a statement of intent, this was probably the closest that was found.

On 18 September 1965, in the year of the bicentenary of Smithson's birth, the Smithsonian Institution awarded to the Royal Society a 14-ct.

Carat (purity)

The karat or carat is a unit of purity for gold alloys.- Measure :Karat purity is measured as 24 times the purity by mass:where...

gold medal bearing a left-facing bust of Smithson.

Ancestors

Articles

- William L. Bird, Jr. "A Suggestion Concerning James Smithson's Concept of 'Increase and Diffusion.'" Technology and Culture Vol. 24 No. 2 (April 1983): 246-255. Refers to a photograph, believed to have been taken by Alexander Graham Bell's wife, of an unidentified man holding the skull of James Smithson on the occasion of Alexander Graham Bell's mission to Genoa, Italy, in 1904 to retrieve Smithson's remains and bring them to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.

Books

Reprinted as Reprinted asExternal links

- James Smithson on the Royal Society website

- The Life of James Smithson, from the website of America's Smithsonian, an exhibition celebrating the 150th anniversary of the Smithsonian Institution

- James Smithson & the Founding of the Smithsonian, from the Smithsonian Institution Archives

- The Library of James Smithson on LibraryThing, compiled by Smithsonian Institution Libraries

- The Library of James Smithson from Smithsonian Institution Libraries