Hugh Childers

Encyclopedia

Hugh Culling Eardley Childers (25 June 1827 – 29 January 1896) was a British

and Australia

n Liberal

statesman

of the nineteenth century. He is perhaps best known for his reform efforts at the Admiralty

and the War Office

. Later in his career, as Chancellor of the Exchequer, his attempt to correct a budget shortfall led to the fall of the Liberal government led by Lord Rosebery.

, the son of Reverend Eardley Childers and his wife Maria Charlotte (née Smith),

sister of Sir Culling Eardley, 3rd Baronet and granddaughter of Sampson Eardley, 1st Baron Eardley

. He was educated at Cheam School

and then both Wadham College, Oxford

and Trinity College, Cambridge

, graduating B.A.

from the latter in 1850. Childers then decided to seek a career in Australia and on 26 October 1850 arrived in Melbourne

, Victoria

along with his wife Emily Walker.

. In 1852 he placed a bill before the state legislature proposing the establishment of a second university for Victoria, following the foundation of the University of Sydney

in 1850. With the receipt of the Royal Assent

in 1853, the University of Melbourne

was founded, with Childers as its first vice-chancellor.

from Cambridge

the same year.

as the Liberal

member for Pontefract

, and served in a minor capacity in the government of Lord Palmerston

, becoming a Civil Lord of the Admiralty in 1864 and Financial Secretary to the Treasury

in 1865.

With the election of Gladstone

With the election of Gladstone

's government in December 1868 he rose to greater prominence, serving as First Lord of the Admiralty. Childers "had a reputation for being hardworking, but inept, autocratic and notoriously overbearing in his dealing with colleagues." He "initiated a determined programme of cost and manpower reductions, fully backed by the Prime Minister, Gladstone described him [Childers] as 'a man likely to scan with a rigid eye the civil expenses of the Naval Service'. He got the naval estimates just below the psychologically important figure of £10,000,000. Childers strengthened his own position as First Lord by reducing the role of the Board of Admiralty to a purely formal one, making meetings rare and short and confining the Naval Lords rigidly to the administrative functions... Initially Childers had the support of the influential Controller of the Navy, Vice-Admiral Sir [Robert] Spencer Robinson

." "His re-organisation of the Admiralty was unpopular and poorly done."

Childers was responsible for the construction of HMS Captain

in defiance of the advice of his professional advisers, the Controller (Robinson) and the Chief Constructor (Edward James Reed

). The Captain was commissioned in April 1870, and sank on the night of 6/7 September 1870. She was, as predicted by Robison and Reed, insufficiently stable. "Shortly before Captain sank, Childers had moved his son, Midshipman Leonard Childers from Reed's designed HMS Monarch

onto Captain; Leonard did not survive." Childers "faced strong criticism following the Court Martial on the loss of Captain, and attempted to clear his name with a 359 page memorandum, a move described as "dubious public ethics". Vice Admiral Sir Robert Spencer Robinson wrote 'His endeavors were directed to throw the blame which might be supposed to attach to himself on those who had throughout expressed their disapproval of such methods of construction'." Childers unfairly blamed Robinson for the loss of the Captain, and as a result of this Robinson was replaced as Third Lord and Controller of the navy in February 1871. "Following the loss of his son and the recriminations that followed, Childers resigned through ill health as First Lord in March 1871."

. The consequent ministerial by-election on 15 August 1872 was the first Parliamentary election to be held after the Ballot Act 1872

required the use of a secret ballot

.

, a position he accepted reluctantly. He therefore had to bear responsibility for cuts in arms expenditure, a policy that provoked controversy when Britain found itself fighting first the Boers in South Africa in 1880

and invading Egypt in 1882

. Childers was also very unpopular with Horse Guards

for his reinforcement and expansion of the Cardwell reforms

. In 1 May 1881 he passed General Order 41, which made a series of improvements known as the Childers reforms

.

in 1882, a post he had coveted. As such, he attempted to implement a conversion of Consols

in 1884. Although the scheme proved a failure, it paved the way for the subsequent conversion in 1888. He attempted to resolve a budget shortfall in June 1885 by increasing alcohol duty and income tax

. His budget was rejected by Parliament

, and the government - already unpopular due to events in Egypt

- was forced out of office. The Earl of Rosebery commented resignedly: "So far as I know the budget is as good a question to go out upon as any other, and Tuesday as good a day."

r for Edinburgh South

(one of the few Liberals who adopted this policy before Gladstone's conversion in 1886). He then served as Home Secretary

in the short-lived ministry of 1886. He was critical of the financial clauses of the first Home Rule Bill, and their withdrawal was largely due to his threat of resignation. Nevertheless, the Bill still failed to pass, and its rejection brought down the Liberal government.

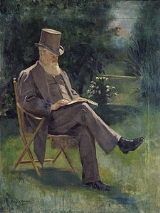

_childers.jpg) He retired from parliament in 1892, and his last piece of work was the drafting of a report for the 1894 "Financial Relations Commission" on Irish

He retired from parliament in 1892, and his last piece of work was the drafting of a report for the 1894 "Financial Relations Commission" on Irish

financial matters, of which he was chairman (generally known as the Childers Commission). This found that, compared to the rest of the United Kingdom, Ireland had been overtaxed on a per capita

basis by some £2 or £3 million annually in previous decades. The matter was finally debated in March 1897. In the following decades Irish nationalists frequently quoted the report as proof that some form of fiscal freedom was needed to end imperial over-taxation, which was prolonging Irish poverty. Their opponents noted that the extra tax received had come from an unduly high consumption of tea

, stout

, whiskey and tobacco

, and not from income tax

. His younger cousin Erskine Childers

wrote a book on the matter in 1911.

Childers' 1894 report was still considered influential in 1925 in considering the mutual financial positions between the new Irish Free State

and the United Kingdom. In 1926 an Irish Senate

debate included claims by some Senators that, with compound interest

, Ireland was owed as much as £1.2 billion by the rest of Britain.

, was a portrait and landscape painter. His wife died in 1875. Childers married Katherine Anne Gilbert 1879, and died in January 1896, aged 68. Towards the end of his ministerial career "HCE" Childers was notable for his girth

, and so acquired the nickname "Here Comes Everybody", which was later used as a motif in Finnegans Wake

by James Joyce

. A cousin, Robert Erskine Childers

, was the author of the famous spy novel The Riddle of the Sands

and father of the fourth President of Ireland

, Erskine Childers

.

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

and Australia

Australia

Australia , officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country in the Southern Hemisphere comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. It is the world's sixth-largest country by total area...

n Liberal

Liberal Party (UK)

The Liberal Party was one of the two major political parties of the United Kingdom during the 19th and early 20th centuries. It was a third party of negligible importance throughout the latter half of the 20th Century, before merging with the Social Democratic Party in 1988 to form the present day...

statesman

Statesman

A statesman is usually a politician or other notable public figure who has had a long and respected career in politics or government at the national and international level. As a term of respect, it is usually left to supporters or commentators to use the term...

of the nineteenth century. He is perhaps best known for his reform efforts at the Admiralty

Admiralty

The Admiralty was formerly the authority in the Kingdom of England, and later in the United Kingdom, responsible for the command of the Royal Navy...

and the War Office

War Office

The War Office was a department of the British Government, responsible for the administration of the British Army between the 17th century and 1964, when its functions were transferred to the Ministry of Defence...

. Later in his career, as Chancellor of the Exchequer, his attempt to correct a budget shortfall led to the fall of the Liberal government led by Lord Rosebery.

Early life

Childers was born in LondonLondon

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

, the son of Reverend Eardley Childers and his wife Maria Charlotte (née Smith),

sister of Sir Culling Eardley, 3rd Baronet and granddaughter of Sampson Eardley, 1st Baron Eardley

Sampson Eardley, 1st Baron Eardley

Sampson Eardley, 1st Baron Eardley , known as Sampson Gideon until 1789, was the son of another Sampson Gideon , a Jewish banker in the City of London who advised the British government in the 1740s and 1750s.He served as Member of Parliament for Cambridgeshire from 1770 to 1780, Midhurst from 1780...

. He was educated at Cheam School

Cheam School

Cheam School is a preparatory school in Headley in the civil parish of Ashford Hill with Headley in the English county of Hampshire. It was founded in 1645 by the Reverend George Aldrich in Cheam, Surrey and has been in operation ever since....

and then both Wadham College, Oxford

Wadham College, Oxford

Wadham College is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom, located at the southern end of Parks Road in central Oxford. It was founded by Nicholas and Dorothy Wadham, wealthy Somerset landowners, during the reign of King James I...

and Trinity College, Cambridge

Trinity College, Cambridge

Trinity College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. Trinity has more members than any other college in Cambridge or Oxford, with around 700 undergraduates, 430 graduates, and over 170 Fellows...

, graduating B.A.

Bachelor of Arts

A Bachelor of Arts , from the Latin artium baccalaureus, is a bachelor's degree awarded for an undergraduate course or program in either the liberal arts, the sciences, or both...

from the latter in 1850. Childers then decided to seek a career in Australia and on 26 October 1850 arrived in Melbourne

Melbourne

Melbourne is the capital and most populous city in the state of Victoria, and the second most populous city in Australia. The Melbourne City Centre is the hub of the greater metropolitan area and the Census statistical division—of which "Melbourne" is the common name. As of June 2009, the greater...

, Victoria

Victoria (Australia)

Victoria is the second most populous state in Australia. Geographically the smallest mainland state, Victoria is bordered by New South Wales, South Australia, and Tasmania on Boundary Islet to the north, west and south respectively....

along with his wife Emily Walker.

Australia

Childers joined the government of Victoria and served as inspector of schools and immigration agent; in 1852 he became a director of the Melbourne, Mount Alexander and Murray River Railway Co. Childers became auditor-general in October 1852 and was nominated to the Victorian Legislative CouncilVictorian Legislative Council

The Victorian Legislative Council, is the upper of the two houses of the Parliament of Victoria, Australia; the lower house being the Legislative Assembly. Both houses sit in Parliament House in Spring Street, Melbourne. The Legislative Council serves as a house of review, in a similar fashion to...

. In 1852 he placed a bill before the state legislature proposing the establishment of a second university for Victoria, following the foundation of the University of Sydney

University of Sydney

The University of Sydney is a public university located in Sydney, New South Wales. The main campus spreads across the suburbs of Camperdown and Darlington on the southwestern outskirts of the Sydney CBD. Founded in 1850, it is the oldest university in Australia and Oceania...

in 1850. With the receipt of the Royal Assent

Royal Assent

The granting of royal assent refers to the method by which any constitutional monarch formally approves and promulgates an act of his or her nation's parliament, thus making it a law...

in 1853, the University of Melbourne

University of Melbourne

The University of Melbourne is a public university located in Melbourne, Victoria. Founded in 1853, it is the second oldest university in Australia and the oldest in Victoria...

was founded, with Childers as its first vice-chancellor.

Return to Britain

Childers retained the vice-chancellorship until his return to Britain in March 1857 and received a M.A.Master's degree

A master's is an academic degree granted to individuals who have undergone study demonstrating a mastery or high-order overview of a specific field of study or area of professional practice...

from Cambridge

University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a public research university located in Cambridge, United Kingdom. It is the second-oldest university in both the United Kingdom and the English-speaking world , and the seventh-oldest globally...

the same year.

Enters British politics

In 1860 he entered ParliamentBritish House of Commons

The House of Commons is the lower house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, which also comprises the Sovereign and the House of Lords . Both Commons and Lords meet in the Palace of Westminster. The Commons is a democratically elected body, consisting of 650 members , who are known as Members...

as the Liberal

Liberal Party (UK)

The Liberal Party was one of the two major political parties of the United Kingdom during the 19th and early 20th centuries. It was a third party of negligible importance throughout the latter half of the 20th Century, before merging with the Social Democratic Party in 1988 to form the present day...

member for Pontefract

Pontefract

Pontefract is an historic market town in West Yorkshire, England. Traditionally in the West Riding, near the A1 , the M62 motorway and Castleford. It is one of the five towns in the metropolitan borough of the City of Wakefield and has a population of 28,250...

, and served in a minor capacity in the government of Lord Palmerston

Henry Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston

Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston, KG, GCB, PC , known popularly as Lord Palmerston, was a British statesman who served twice as Prime Minister in the mid-19th century...

, becoming a Civil Lord of the Admiralty in 1864 and Financial Secretary to the Treasury

Financial Secretary to the Treasury

Financial Secretary to the Treasury is a junior Ministerial post in the British Treasury. It is the 4th most significant Ministerial role within the Treasury after the Chancellor of the Exchequer, the Chief Secretary to the Treasury, and the Paymaster General...

in 1865.

First Lord of the Admiralty

William Ewart Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone FRS FSS was a British Liberal statesman. In a career lasting over sixty years, he served as Prime Minister four separate times , more than any other person. Gladstone was also Britain's oldest Prime Minister, 84 years old when he resigned for the last time...

's government in December 1868 he rose to greater prominence, serving as First Lord of the Admiralty. Childers "had a reputation for being hardworking, but inept, autocratic and notoriously overbearing in his dealing with colleagues." He "initiated a determined programme of cost and manpower reductions, fully backed by the Prime Minister, Gladstone described him [Childers] as 'a man likely to scan with a rigid eye the civil expenses of the Naval Service'. He got the naval estimates just below the psychologically important figure of £10,000,000. Childers strengthened his own position as First Lord by reducing the role of the Board of Admiralty to a purely formal one, making meetings rare and short and confining the Naval Lords rigidly to the administrative functions... Initially Childers had the support of the influential Controller of the Navy, Vice-Admiral Sir [Robert] Spencer Robinson

Robert Spencer Robinson

Admiral Sir Robert Spencer Robinson KCB was a British naval officer, who served as two five-year terms as Controller of the Navy from February 1861 to February 1871, and was therefore responsible for the procurement of warships at a time when the Royal Navy was changing over from unarmoured wooden...

." "His re-organisation of the Admiralty was unpopular and poorly done."

Childers was responsible for the construction of HMS Captain

HMS Captain (1869)

HMS Captain was an unsuccessful warship built for the Royal Navy due to public pressure. She was a masted turret ship, designed and built by a private contractor against the wishes of the Controller's department...

in defiance of the advice of his professional advisers, the Controller (Robinson) and the Chief Constructor (Edward James Reed

Edward James Reed

Sir Edward James Reed , KCB, FRS, was a British naval architect, author, politician, and railroad magnate. He was the Chief Constructor of the Royal Navy from 1863 until 1870...

). The Captain was commissioned in April 1870, and sank on the night of 6/7 September 1870. She was, as predicted by Robison and Reed, insufficiently stable. "Shortly before Captain sank, Childers had moved his son, Midshipman Leonard Childers from Reed's designed HMS Monarch

HMS Monarch (1868)

HMS Monarch was the first sea-going warship to carry her guns in turrets, and the first British warship to carry guns of calibre.-Design:...

onto Captain; Leonard did not survive." Childers "faced strong criticism following the Court Martial on the loss of Captain, and attempted to clear his name with a 359 page memorandum, a move described as "dubious public ethics". Vice Admiral Sir Robert Spencer Robinson wrote 'His endeavors were directed to throw the blame which might be supposed to attach to himself on those who had throughout expressed their disapproval of such methods of construction'." Childers unfairly blamed Robinson for the loss of the Captain, and as a result of this Robinson was replaced as Third Lord and Controller of the navy in February 1871. "Following the loss of his son and the recriminations that followed, Childers resigned through ill health as First Lord in March 1871."

1871-1880

Following his resignation he spent some months on the Continent, and recovered sufficiently to take office in 1872 as Chancellor of the Duchy of LancasterChancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster

The Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster is, in modern times, a ministerial office in the government of the United Kingdom that includes as part of its duties, the administration of the estates and rents of the Duchy of Lancaster...

. The consequent ministerial by-election on 15 August 1872 was the first Parliamentary election to be held after the Ballot Act 1872

Ballot Act 1872

The Ballot Act 1872 was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that introduced the requirement that parliamentary and local government elections in the United Kingdom be held by secret ballot.-Background:...

required the use of a secret ballot

Secret ballot

The secret ballot is a voting method in which a voter's choices in an election or a referendum are anonymous. The key aim is to ensure the voter records a sincere choice by forestalling attempts to influence the voter by intimidation or bribery. The system is one means of achieving the goal of...

.

Secretary for War

When the Liberals regained power in 1880, Childers was appointed Secretary for WarSecretary of State for War

The position of Secretary of State for War, commonly called War Secretary, was a British cabinet-level position, first held by Henry Dundas . In 1801 the post became that of Secretary of State for War and the Colonies. The position was re-instated in 1854...

, a position he accepted reluctantly. He therefore had to bear responsibility for cuts in arms expenditure, a policy that provoked controversy when Britain found itself fighting first the Boers in South Africa in 1880

First Boer War

The First Boer War also known as the First Anglo-Boer War or the Transvaal War, was fought from 16 December 1880 until 23 March 1881-1877 annexation:...

and invading Egypt in 1882

Urabi Revolt

The Urabi Revolt or Orabi Revolt , also known as the Orabi Revolution, was an uprising in Egypt in 1879-82 against the Khedive and European influence in the country...

. Childers was also very unpopular with Horse Guards

Horse Guards

Horse Guards or horse guards can refer to:* A Household Cavalry regiment:** Troops of the Horse Guards Regiment of the British Army from 1658-1788** The Royal Horse Guards, which is now part of the Blues and Royals...

for his reinforcement and expansion of the Cardwell reforms

Cardwell Reforms

The Cardwell Reforms refer to a series of reforms of the British Army undertaken by Secretary of State for War Edward Cardwell between 1868 and 1874.-Background:...

. In 1 May 1881 he passed General Order 41, which made a series of improvements known as the Childers reforms

Childers Reforms

The Childers Reforms restructured the infantry regiments of the British army. The reforms were undertaken by Secretary of State for War Hugh Childers in 1881, and were a continuation of the earlier Cardwell reforms....

.

Chancellor of the Exchequer

Childers became Chancellor of the ExchequerChancellor of the Exchequer

The Chancellor of the Exchequer is the title held by the British Cabinet minister who is responsible for all economic and financial matters. Often simply called the Chancellor, the office-holder controls HM Treasury and plays a role akin to the posts of Minister of Finance or Secretary of the...

in 1882, a post he had coveted. As such, he attempted to implement a conversion of Consols

Consols

Consol is a form of British government bond , dating originally from the 18th century. The first consols were originally issued in 1751...

in 1884. Although the scheme proved a failure, it paved the way for the subsequent conversion in 1888. He attempted to resolve a budget shortfall in June 1885 by increasing alcohol duty and income tax

Income tax

An income tax is a tax levied on the income of individuals or businesses . Various income tax systems exist, with varying degrees of tax incidence. Income taxation can be progressive, proportional, or regressive. When the tax is levied on the income of companies, it is often called a corporate...

. His budget was rejected by Parliament

British House of Commons

The House of Commons is the lower house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, which also comprises the Sovereign and the House of Lords . Both Commons and Lords meet in the Palace of Westminster. The Commons is a democratically elected body, consisting of 650 members , who are known as Members...

, and the government - already unpopular due to events in Egypt

Charles George Gordon

Major-General Charles George Gordon, CB , known as "Chinese" Gordon, Gordon Pasha, and Gordon of Khartoum, was a British army officer and administrator....

- was forced out of office. The Earl of Rosebery commented resignedly: "So far as I know the budget is as good a question to go out upon as any other, and Tuesday as good a day."

Home Secretary

At the subsequent election in December 1885 Childers lost his Pontefract seat, but returned as an independent Home RuleHome rule

Home rule is the power of a constituent part of a state to exercise such of the state's powers of governance within its own administrative area that have been devolved to it by the central government....

r for Edinburgh South

Edinburgh South (UK Parliament constituency)

Edinburgh South is a constituency of the House of Commons of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, first used in the general election of 1885. It elects one Member of Parliament by the first past the post system of election...

(one of the few Liberals who adopted this policy before Gladstone's conversion in 1886). He then served as Home Secretary

Home Secretary

The Secretary of State for the Home Department, commonly known as the Home Secretary, is the minister in charge of the Home Office of the United Kingdom, and one of the country's four Great Offices of State...

in the short-lived ministry of 1886. He was critical of the financial clauses of the first Home Rule Bill, and their withdrawal was largely due to his threat of resignation. Nevertheless, the Bill still failed to pass, and its rejection brought down the Liberal government.

Retirement and the Childers Commission

_childers.jpg)

Ireland

Ireland is an island to the northwest of continental Europe. It is the third-largest island in Europe and the twentieth-largest island on Earth...

financial matters, of which he was chairman (generally known as the Childers Commission). This found that, compared to the rest of the United Kingdom, Ireland had been overtaxed on a per capita

Per capita

Per capita is a Latin prepositional phrase: per and capita . The phrase thus means "by heads" or "for each head", i.e. per individual or per person...

basis by some £2 or £3 million annually in previous decades. The matter was finally debated in March 1897. In the following decades Irish nationalists frequently quoted the report as proof that some form of fiscal freedom was needed to end imperial over-taxation, which was prolonging Irish poverty. Their opponents noted that the extra tax received had come from an unduly high consumption of tea

Tea

Tea is an aromatic beverage prepared by adding cured leaves of the Camellia sinensis plant to hot water. The term also refers to the plant itself. After water, tea is the most widely consumed beverage in the world...

, stout

Stout

Stout is a dark beer made using roasted malt or barley, hops, water and yeast. Stouts were traditionally the generic term for the strongest or stoutest porters, typically 7% or 8%, produced by a brewery....

, whiskey and tobacco

Tobacco

Tobacco is an agricultural product processed from the leaves of plants in the genus Nicotiana. It can be consumed, used as a pesticide and, in the form of nicotine tartrate, used in some medicines...

, and not from income tax

Income tax

An income tax is a tax levied on the income of individuals or businesses . Various income tax systems exist, with varying degrees of tax incidence. Income taxation can be progressive, proportional, or regressive. When the tax is levied on the income of companies, it is often called a corporate...

. His younger cousin Erskine Childers

Robert Erskine Childers

Robert Erskine Childers DSC , universally known as Erskine Childers, was the author of the influential novel Riddle of the Sands and an Irish nationalist who smuggled guns to Ireland in his sailing yacht Asgard. He was executed by the authorities of the nascent Irish Free State during the Irish...

wrote a book on the matter in 1911.

Childers' 1894 report was still considered influential in 1925 in considering the mutual financial positions between the new Irish Free State

Irish Free State

The Irish Free State was the state established as a Dominion on 6 December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty, signed by the British government and Irish representatives exactly twelve months beforehand...

and the United Kingdom. In 1926 an Irish Senate

Seanad Éireann (Irish Free State)

Seanad Éireann was the upper house of the Oireachtas of the Irish Free State from 1922–1936. It has also been known simply as the Senate, or as the First Seanad. The Senate was established under the 1922 Constitution of the Irish Free State but a number of constitutional amendments were...

debate included claims by some Senators that, with compound interest

Compound interest

Compound interest arises when interest is added to the principal, so that from that moment on, the interest that has been added also itself earns interest. This addition of interest to the principal is called compounding...

, Ireland was owed as much as £1.2 billion by the rest of Britain.

Family

Childers married Emily Walker in 1850. They had six sons and two daughters. One of their daughters, Emily Milly ChildersMilly Childers

Emily Maria Eardley Childers , known as Milly, was an English painter of the later Victorian era and the early twentieth century....

, was a portrait and landscape painter. His wife died in 1875. Childers married Katherine Anne Gilbert 1879, and died in January 1896, aged 68. Towards the end of his ministerial career "HCE" Childers was notable for his girth

Obesity

Obesity is a medical condition in which excess body fat has accumulated to the extent that it may have an adverse effect on health, leading to reduced life expectancy and/or increased health problems...

, and so acquired the nickname "Here Comes Everybody", which was later used as a motif in Finnegans Wake

Finnegans Wake

Finnegans Wake is a novel by Irish author James Joyce, significant for its experimental style and resulting reputation as one of the most difficult works of fiction in the English language. Written in Paris over a period of seventeen years, and published in 1939, two years before the author's...

by James Joyce

James Joyce

James Augustine Aloysius Joyce was an Irish novelist and poet, considered to be one of the most influential writers in the modernist avant-garde of the early 20th century...

. A cousin, Robert Erskine Childers

Robert Erskine Childers

Robert Erskine Childers DSC , universally known as Erskine Childers, was the author of the influential novel Riddle of the Sands and an Irish nationalist who smuggled guns to Ireland in his sailing yacht Asgard. He was executed by the authorities of the nascent Irish Free State during the Irish...

, was the author of the famous spy novel The Riddle of the Sands

The Riddle of the Sands

The Riddle of the Sands: A Record of Secret Service is a 1903 novel by Erskine Childers. It is an early example of the espionage novel, with a strong underlying theme of militarism...

and father of the fourth President of Ireland

President of Ireland

The President of Ireland is the head of state of Ireland. The President is usually directly elected by the people for seven years, and can be elected for a maximum of two terms. The presidency is largely a ceremonial office, but the President does exercise certain limited powers with absolute...

, Erskine Childers

Erskine Hamilton Childers

Erskine Hamilton Childers served as the fourth President of Ireland from 1973 until his death in 1974. He was a Teachta Dála from 1938 until 1973...

.

See also

- Childers, QueenslandChilders, QueenslandChilders is a town in southern Queensland, Australia, situated at the junction of the Bruce and Isis Highways. The township lies north of the state capital Brisbane and south-west of Bundaberg. Childers is located within Bundaberg Region Local Government Area. At the 2006 census, Childers had a...

, town named after Childers - HMAS Childers (ACPB 93)HMAS Childers (ACPB 93)HMAS Childers is an Armidale class patrol boat of the Royal Australian Navy . Named for the towns of Childers, Queensland and Childers, Victoria, Childers is the only ship in the RAN to be named after two towns....

, Australian ship named after the town

Biography

- The Life and Correspondence of the Rt. Hon. Hugh C.E. Childers, Spencer Childers, 1901

- The Educational Activities in Victoria of the Right Hon. H. C. E. Childers, E. Sweetman, 1940