Donnchadh, Earl of Carrick

Encyclopedia

Donnchadh (Latinised Duncanus, later Anglicised

as Duncan) was a Gall-Gaidhil prince and Scottish

magnate in what is now south-western Scotland, whose career stretched from the last quarter of the 12th century until his death in 1250. His father, Gille-Brighde of Galloway, and his uncle, Uhtred of Galloway, were the two rival sons of Fergus

, "King" or "Lord" of Galloway

. As a result of Gille-Brighde's conflict with Uhtred and the Scottish monarch William the Lion

, Donnchadh became a hostage of King Henry II of England

. He probably remained in England for almost a decade before returning north on the death of his father. Although denied succession to all the lands of the Gall-Gaidhil, he was granted lordship over Carrick

in the north-west.

Little is known about Donnchadh's life and rule. Allied to John de Courcy

, Donnchadh fought battles in Ireland and acquired land there that he subsequently lost. A patron of religious houses, particularly Melrose Abbey

and North Berwick priory nunnery, he attempted to establish a monastery

in his own territory, at Crossraguel

. He married the daughter of Alan fitz Walter, a leading member of the family later known as the House of Stewart—future monarchs of Scotland and England. Donnchadh was the first mormaer

("earl

") of Carrick, a region he ruled for more than six decades, making him one of the longest serving magnate

s in medieval Scotland

. His descendants include the Bruce and Stewart Kings of Scotland, and probably the Campbell

Dukes of Argyll

.

s provide a little information about some of his activities, but overall their usefulness is limited; this is because no charter-collections (called cartularies) from the Gaelic south-west

have survived the Middle Ages, and the only surviving charters relevant to Donnchadh's career come from the heavily Normanised English-speaking area to the east. Principally, the relevant charters record his acts of patronage towards religious houses, but incidental details mentioned in the body of these texts and the witness lists subscribed to them are useful for other matters.

Some English government records describe his activities in relation to Ireland, and occasional chronicle

entries from England and the English-speaking regions of what became south-eastern Scotland record other important details. Aside from the Chronicle of Melrose

, the most significant of these sources are the works of Roger of Hoveden

, and the material preserved in the writings of John of Fordun

and Walter Bower

.

Roger of Hoveden wrote two important works: the Gesta Henrici II ("Deeds of Henry II", alternatively titled Gesta Henrici et Ricardi, "Deeds of Henry and Richard") and the Chronica, the latter a re-worked and supplemented version of the former. These works are the most important and valuable sources for Scottish history in the late 12th century. The Gesta Henrici II covers the period from 1169 to April 1192, and the Chronica covers events until 1201. Roger of Hoveden is particularly important in relation to what is now south-western Scotland, the land of the Gall-Gaidhil. He served as an emissary in the region in 1174 on behalf of the English monarch, and thus his account of, for example, the approach of Donnchadh's father Gille-Brighde towards the English king comes from a witness. Historians rely on Roger's writings for a number of important details about Donnchadh's life: that Gille-Brighde handed Donnchadh over as a hostage to Henry II

under the care of Hugh de Morwic, Sheriff of Cumberland; that Donnchcadh married the daughter of Alan fitz Walter under protest from the Scottish king; and that Donnchadh fought a battle in Ireland in 1197 assisting John de Courcy

, Prince of Ulster.

Another important chronicle source is the material preserved in John of Fordun's Chronica gentis Scottorum ("Chronicle of the Scottish people") and Walter Bower's Scotichronicon

. John of Fordun's work, which survives on its own, was incorporated in the following century into the work of Bower. Fordun's Chronica was written and compiled between 1384 and August 1387. Despite the apparently late date, Scottish textual historian Dauvit Broun

has shown that Fordun's work in fact consists of two earlier pieces, Gesta Annalia I and Gesta Annalia II, the former written before April 1285 and covering the period from King Máel Coluim mac Donnchada (Malcolm III, died 1093) to 2 February 1285. Gesta Annalia I appears to have been based on an even earlier text, about the descendants of Saint Margaret of Scotland

, produced at Dunfermline Abbey

. Thus material from these works concerning the late 12th and early 13th century Gall-Gaidhil may represent, despite the apparent late date, reliable contemporary or near-contemporary accounts.

Donnchadh's territory lay in what is now Scotland south of the River Forth

Donnchadh's territory lay in what is now Scotland south of the River Forth

, a multi-ethnic region during the late 12th century. North of the Forth was the Gaelic kingdom of Scotland (Alba), which under its partially Normanised kings exercised direct or indirect control over most of the region to the south as far as the borders of Northumberland

and Cumberland

. Lothian

and the Merse were the heartlands of the northern part of the old English Earldom of Northumbria

, and in the late 12th century the people of these regions, as well as the people of Lauderdale

, Eskdale

, Liddesdale

, and most of Teviotdale and Annandale, were English in language and regarded themselves as English by ethnicity, despite having been under the control of the king of the Scots for at least a century.

Clydesdale

(or Strathclyde) was the heartland of the old Kingdom of Strathclyde

; by Donnchadh's day the Scots had settled many English and Continental Europeans (principally Flemings) in the region, and administered it through the sheriffdom of Lanark. Gaelic too had penetrated much of the old Northumbrian and Strathclyde territory, coming from the west, south-west and the north, a situation that led historian Alex Woolf

to compare the region to the Balkans. The British language

of the area, as a result of such developments, was probably either dead or almost dead, perhaps surviving only in the uplands of Clydesdale, Tweeddale

and Annandale.

The rest of the region was settled by the people called Gall-Gaidhil (modern Scottish Gaelic: Gall-Ghàidheil) in their own language, variations of Gallwedienses in Latin

, and normally Galwegians or Gallovidians in modern English. References in the 11th century to the kingdom of the Gall-Gaidhil centre it far to the north of what is now Galloway

. Kingarth

(Cenn Garadh) and Eigg

(Eic) were described as "in Galloway" (Gallgaidelaib) by the Martyrology of Óengus, in contrast to Whithorn

—part of modern Galloway—which was named as lying within another kingdom, The Rhinns

(Na Renna). These areas had been part of the Kingdom of Northumbria until the 9th century, and afterward were transformed by a process very poorly documented, but probably carried out by numerous small bands of culturally Scandinavian but linguistically Gaelic warrior-settlers moving in from Ireland and southern Argyll. "Galloway" today only refers to the lands of Rhinns, Farines, Glenken, Desnes Mór and Desnes Ioan (that is, Wigtownshire

and the Stewartry of Kirkcudbright), but this is due to the territorial changes that took place in and around Donnchadh's lifetime rather than being the contemporary definition. For instance, a 12th century piece of marginalia

located the island of Ailsa Craig

"lying between Gallgaedelu [Galloway] and Cend Tiri [Kintyre]", while a charter of Máel Coluim IV ("Malcolm IV") describes Strathgryfe

, Cunningham

, Kyle

and Carrick as the four cadrez (probably from ceathramh, "quarter"s) of Galloway; an Irish annal entry for the year 1154 designated galleys from Arran

, Kintyre, the Isle of Man as Gallghaoidhel, "Galwegian".

By the middle of the 12th century the former territory of the kingdom of the Rhinns was part of Galloway kingdom, but the area to the north was not. Strathgryfe, Kyle and Cunningham had come under the control of the Scottish king in the early 12th century, much of it given over to soldiers of French or Anglo-French origin. Strathgryfe and most of Kyle had been given to Walter fitz Alan under King David I

, with Hugh de Morville

taking Cunningham. Strathnith still had a Gaelic ruler (ancestor of the famous Thomas Randolph, 1st Earl of Moray), but he was not part of the kingdom of Galloway. The rest of the region—the Rhinns, Farines, Carrick, Desnes Mór and Desnes Ioan, and the sparsely settled uplands of Glenken—was probably under the control of the sons of Fergus

, King of Galloway, in the years before Donnchadh's career in the region.

, petty king of Argyll

in the third quarter of the 12th century. As the original territory of the Gall-Gaidhil kingdom probably adjoined or included Argyll, Alex Woolf has suggested that Fergus and Somhairle were brothers or cousins.

There is a "body of circumstantial evidence" that suggests Donnchadh's mother was a daughter or sister of Donnchadh II, Earl of Fife. This includes Donnchadh's association with the Cistercian nunnery of North Berwick, founded by Donnchadh II of Fife's father, Donnchadh I of Fife

; close ties seem to have existed between the two families, while Donnchadh's own name is further evidence. The historian who suggested this in 2000, Richard Oram

, came to regard this conjecture as certain by 2004.

Roger of Hoveden described Uhtred of Galloway as a consanguinus ("cousin") of King Henry II of England, an assertion that has given rise to the theory that, since Gille-Brighde is never described as such, they must have been from different mothers. Fergus must therefore, according to the theory, have had two wives, one of whom was a bastard daughter of Henry I

Roger of Hoveden described Uhtred of Galloway as a consanguinus ("cousin") of King Henry II of England, an assertion that has given rise to the theory that, since Gille-Brighde is never described as such, they must have been from different mothers. Fergus must therefore, according to the theory, have had two wives, one of whom was a bastard daughter of Henry I

; that is, Uhtred and his descendants were related to the English royal family, while Gille-Brighde and his descendants were not. However, according to historian G. W. S. Barrow

, the theory is disproved by one English royal document, written in the name of King John of England

, which likewise asserts that Donnchadh was John's cousin.

It is unclear how many siblings Donnchadh had, but two at least are known. The first, Máel Coluim, led the forces that besieged Gille-Brighde's brother Uhtred on "Dee island" (probably Threave) in Galloway in 1174. This Máel Coluim captured Uhtred, who subsequently, in addition to being blinded and castrated, had his tongue cut out. Nothing more is known of Máel Coluim's life; there is speculation by some modern historians that he was illegitimate. Another brother appears in the records of Paisley Abbey

. In 1233, one Gille-Chonaill Manntach, "the Stammerer" (recorded Gillokonel Manthac), gave evidence regarding a land dispute in Strathclyde; the document described him as the brother of the Earl of Carrick, who at that time was Donnchadh.

Having defeated his brother, Gille-Brighde unsuccessfully sought to become a direct vassal of Henry II, king of England. An agreement was obtained with Henry in 1176, Gille-Brighde promising to pay him 1000 mark

s of silver and handing over his son Donnchadh as a hostage. Donnchadh was taken into the care of Hugh de Morwic, sheriff of Cumberland

. The agreement seems to have included recognising Donnchadh's right to inherit Gille-Brighde's lands, for nine years later, in the aftermath of Gille-Brighde's death, when Uhtred's son Lochlann (Roland) invaded western Galloway, Roger of Hoveden described the action as "contrary to [Henry's] prohibition".

The activities of Donnchadh's father Gille-Brighde after 1176 are unclear, but some time before 1184 King William raised an army to punish Gille-Brighde "and the other Galwegians who had wasted his land and slain his vassals"; he held off the endeavour, probably because he was worried about the response of Gille-Brighde's protector Henry II. There were raids on William's territory until Gille-Brighde's death in 1185. The death of Gille-Brighde prompted Donnchadh's cousin Lochlann, supported by the Scottish king, to attempt a takeover, thus threatening Donnchadh's inheritance. At that time Donnchadh was still a hostage in the care of Hugh de Morwic.

The Gesta Annalia I claimed that Donnchadh's patrimony was defended by chieftains called Somhairle ("Samuel"), Gille-Patraic, and Eanric Mac Cennetig ("Henry Mac Kennedy"). Lochlann and his army met these men in battle on 4 July 1185 and, according to the Chronicle of Melrose, killed Gille-Patraic and a substantial number of his warriors. Another battle took place on 30 September, and although Lochlann's forces were probably victorious, killing opponent leader Gille-Coluim, the encounter led to the death of Lochlann's unnamed brother. Lochlann's activities provoked a response from King Henry who, according to historian Richard Oram

, "was not prepared to accept a fait accompli that disinherited the son of a useful vassal, flew in the face of the settlement which he had imposed ... and deprived him of influence over a vitally strategic zone on the north-west periphery of his realm".

According to Hoveden, in May 1186 Henry ordered the king and magnates of Scotland to subdue Lochlann; in response Lochlann "collected numerous horse and foot and obstructed the entrances to Galloway and its roads to what extent he could". Richard Oram did not believe that the Scots really intended to do this, as Lochlann was their dependent and probably acted with their consent; this, Oram argued, explains why Henry himself raised an army and marched north to Carlisle. When Henry arrived he instructed King William and his brother David, Earl of Huntingdon, to come to Carlisle, and to bring Lochlann with them.

Lochlann ignored Henry's summons until an embassy consisting of Hugh de Puiset

, Bishop of Durham and Justiciar Ranulf de Glanville provided him with hostages as a guarantee of his safety; when he agreed to travel to Carlisle with the king's ambassadors. Hoveden wrote that Lochlann was allowed to keep the land that his father Uhtred had held "on the day he was alive and dead", but that the land of Gille-Brighde that was claimed by Donnchadh, son of Gille-Brighde, would be settled in Henry's court, to which Lochlann would be summoned. Lochlann agreed to these terms. King William and Earl David swore an oath to enforce the agreement, with Jocelin, Bishop of Glasgow, instructed to excommunicate any party that should breach their oath.

When Donnchadh adopted or was given the title of "earl" (Latin: comes), or in his own language mormaer, is a debated question. Historian Alan Orr Anderson

argued that he began using the title of comes between 1214 and 1216, based on Donnchadh's appearance as a witness to two charters issued by Thomas de Colville; the first, known as Melrose 193 (this being its number in Cosmo Innes

's printed version of the cartulary), was dated by Anderson to 1214. In this charter, Donnchadh has no title. By contrast Donnchadh was styled comes in a charter dated by Anderson to 1216, Melrose 192.

Oram however pointed out that Donnchadh was styled comes in a grant to Melrose Abbey witnessed by Richard de Morville (Melrose 32), who died in 1196. If the wording in this charter is accurate, then Donnchadh was using the title before Richard's death: that is, in or before 1196. Furthermore, while Anderson dated Melrose 192 with reference to Abbot William III de Courcy (abbot of Melrose from 1215 to 1216), Oram identified Abbot William as Abbot William II (abbot from 1202 to 1206). Whenever Donnchadh adopted the title, he is the first known "earl" of the region.

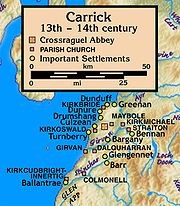

Carrick was located in the Firth of Clyde

Carrick was located in the Firth of Clyde

, in the Irish Sea

region far from the main centres of Scottish and Anglo-Norman influence lying to its east and south-east. Carrick was separated from Kyle in the north and north-east by the river Doon

, and from Galloway-proper by Glenapp and by the adjacent hills and forests. There were three main rivers, the Doon, the Girvan and the Stinchar

, though most of the province was hilly, meaning that most wealth came from animal husbandry

rather than arable farming

. The population of Carrick, like that in neighbouring Galloway, consisted of kin-groups governed by a "chief" or "captain" (cenn, Latin capitaneus). Above these captains was the Cenn Cineoil ("kenkynolle"), the "kin-captain" of Carrick, a position held by the mormaer; it was not until after Donnchadh's death that these two positions were separated. The best recorded groups are Donnchadh's own group (known only as de Carrick, "of Carrick") and the Mac Cennétig (Kennedy) family

, who seem to have provided the earldom's hereditary stewards.

The population was governed under these leaders by a customary law that remained distinct from the common law of Scotland for the remainder of the Middle Ages. One documented aspect of Carrick and Galloway law was the power of sergeants (an original Gaelic word Latinised as Kethres), officials of the earl or of other captains, to claim one night of free hospitality (a privilege called sorryn et frithalos), and to accuse and arrest with little restriction. The personal demesne

, or lands, of the earl was probably extensive in Donnchadh's time; in 1260, during the minority of Donnchadh's descendant Countess Marjory of Carrick, an assessment made by the Scottish king showed that the earls had estates throughout the province, in upland locations like Straiton

, Glengennet and Bennan, as well as in the east in locations such as Turnberry

and Dalquharran.

use of saltpan

s from his land at Turnberry. Between 1189 and 1198 he had granted the church of Maybothelbeg ("Little Maybole

") and the lands of Beath (Bethóc) to this Cistercian house. The grant is mentioned by the Chronicle of Melrose, under the year 1193: These estates were very rich, and became attached to Melrose's "super-grange" at Mauchline

in Kyle. In 1285 Melrose Abbey was able to persuade the earl of the time to force its tenants in Carrick to use the lex Anglicana (the "English law").

Witness to both grants were some prominent churchman connected with Melrose: magnates like Earl Donnchadh II of Fife, the latter's son Máel Coluim

, Gille Brigte, Earl of Strathearn

, as well as probable members of Donnchadh's retinue, like Gille-Osald mac Gille-Anndrais, Gille-nan-Náemh mac Cholmain, Gille-Chríst Bretnach ("the Briton"), and Donnchadh's chamberlain

Étgar mac Muireadhaich. Áedh son of the mormaer of Lennox also witnessed these grants, and sometime between 1208 and 1214 Donnchadh (as "Lord Donnchadh") subscribed (i.e. his name was written at the bottom, as a "witness" to) a charter of Maol Domhnaich, Earl of Lennox

, son and heir of Mormaer Ailean II

, to the bishopric of Glasgow regarding the church of Campsie

.

There are records of patronage towards the nunnery of North Berwick, a house founded by Donnchadh's probable maternal grandfather or great-grandfather Donnchadh I of Fife. He gave that house the rectorship of the church of St Cuthbert of Maybole sometime between 1189 and 1250. In addition to Maybole, he gave the church of St Brigit at Kirkbride to the nuns, as well as a grant of 3 marks from a place called Barrebeth. Relations with the bishop of Glasgow, within whose diocese Carrick lay, are also attested. For instance, on 21 July 1225, at Ayr

in Kyle, Donnchadh made a promise of tithe

s to Walter

, Bishop of Glasgow.

Donnchadh's most important long-term patronage was a series of gifts to the Cluniac Abbey of Paisley that led to the foundation of a monastery at Crossraguel (Crois Riaghail). At some date before 1227 he granted Crossraguel and a place called Suthblan to Paisley, a grant confirmed by Pope Honorius III

Donnchadh's most important long-term patronage was a series of gifts to the Cluniac Abbey of Paisley that led to the foundation of a monastery at Crossraguel (Crois Riaghail). At some date before 1227 he granted Crossraguel and a place called Suthblan to Paisley, a grant confirmed by Pope Honorius III

on 23 January 1227. A royal confirmation by King Alexander III of Scotland

dated to 25 August 1236 shows that Donnchadh granted the monastery the churches of Kirkoswald (Turnberry), Straiton and Dalquharran (Old Dailly

). He may also have given the churches of Girvan

and Kirkcudbright-Innertig (Ballantrae

).

It is clear from several sources that Donnchadh made these grants on the condition that the Abbey of Paisley established a Cluniac house in Carrick, but that the Abbey did not fulfil this condition, arguing that it was not obliged to do so. The Bishop of Glasgow intervened in 1244 and determined that a house of Cluniac monks from Paisley should indeed be founded there, that the house should be exempt from the jurisdiction of Paisley save recognition of the common Cluniac Order, but that the Abbot of Paisley could visit the house annually. After the foundation Paisley was to hand over its Carrick properties to the newly established monastery.

A papal bull

of 11 July 1265 reveals that Paisley Abbey built only a small oratory

served by Paisley monks. Twenty years after the bishop's ruling Paisley complained to the papacy, which led Pope Clement IV

to issue two bulls, dated 11 June 1265 and 6 February 1266, appointing mandatories to settle the dispute; the results of their deliberations are unknown. Crossraguel was not finally founded until about two decades after Donnchadh's death, probably by 1270; its first abbot, Abbot Patrick, is attested between 1274 and 1292.

. The marriage is known from Roger of Hoveden's Chronica, which recorded that in 1200 Donnchadh: The marriage bound Donnchadh closer to the Anglo-French circles of the northern part of the region south of the Forth, while from Alan's point of view it was part of a series of moves to expand his territory further into former Gall-Gaidhil lands, moves that had included an alliance a few years earlier with another Firth of Clyde Gaelic prince, Raghnall mac Somhairle

(Rǫgnvaldr, son of Sumarliði or Somerled

).

Charter evidence reveals two Anglo-Normans present in Donnchadh's territory. Some of Donnchadh's charters to Melrose were subscribed by an Anglo-Norman knight named Roger de Skelbrooke, who appears to have been Lord of Greenan

. De Skelbrooke himself made grants to Melrose regarding the land of Drumeceisuiene (i.e. Drumshang), grants confirmed by "his lord" Donnchadh. This knight gave Melrose fishing rights in the river Doon, rights confirmed by Donnchadh too and later by Roger's son-in-law and successor Ruaidhri mac Gille-Escoib (Raderic mac Gillescop).

The other known Anglo-French knight was Thomas de Colville. Thomas (nicknamed "the Scot") was the younger son of the lord of Castle Bytham

, a significant landowner in Yorkshire

and Lincolnshire

Around 1190 he was constable of Dumfries

, the royal castle which had been planted in Strathnith by the Scottish king, probably overrun by the Gall-Gaidhil in the revolt of 1174 before being restored afterwards. Evidence that he possessed land in the region under Donnchadh's overlordship comes from the opening years of the 13th century when he made a grant of land around Dalmellington

to the Cistercians of Vaudey Abbey

. Historians G. W. S. Barrow and Hector MacQueen

both thought that Thomas' nickname "the Scot" (which then could mean "a Gael" as well as someone from north of the Forth), is a reflection of Thomas' exposure to the culture of the south-west during his career there.

It is not known how these two men acquired the patronage of Donnchadh or his family. Writing in 1980 the historian of Anglo-Norman Scotland G. W. S. Barrow could find no cause for their presence in the area, and declared that they were "for the present impossible to account for". As Richard Oram pointed out, in one of his charters Roger de Skelbrooke called Donnchadh's father Gille-Brighde "my lord", indicating that Donnchadh probably inherited them in his territory. Neither of them left traceable offspring in the region, and even if they did represent for Carrick what could have been the embryonic stages of the kind of Normanisation that was taking place further east, the process was halted during Donnchadh's period as ruler. Vaudey Abbey transferred the land granted to it by Donnchadh to Melrose Abbey in 1223, because it was "useless and dangerous to them, both on account of the absence of law and order, and by reason of the insidious attacks of a barbarous people".

, whose early life was probably spent just across the Irish Sea

in Cumbria

, invaded the Ulaidh (eastern Ulster) in 1177 with the aim of conquest. After defeating the region's king Ruaidhrí Mac Duinn Shléibhe, de Courcy was able to take control of a large amount of territory, though not without encountering further resistance among the native Irish . Cumbria was only a short distance too from the lands of the Gall-Gaidhil, and around 1180 John de Courcy married Donnchadh's cousin Affraic inghen Gofraidh, whose father Guðrøðr (Gofraidh), King of Mann

, was son of Donnchadh's aunt. Guðrøðr, who was thus Donnchadh's cousin, had in turn married a daughter of the Mac Lochlainn ruler of Tir Eoghain, another Ulster principality. Marriage thus connected Donnchadh and the other Gall-Gaidhil princes to several players in Ulster affairs.

The earliest information on Donnchadh's and indeed Gall-Gaidhil involvement in Ulster comes from Roger of Hoveden's entry about the death of Jordan de Courcy, John's brother. It related that in 1197, after Jordan's death, John sought vengeance and No more light is shed upon Donnchadh's involvement at this point.

Donnchadh's interests in the area were damaged when de Courcy lost his territory in eastern Ulster to his rival Hugh de Lacy in 1203. John de Courcy, with help from his wife's brother King Rǫgnvaldr Guðrøðarson (Raghnall mac Gofraidh) and perhaps from Donnchadh, tried to regain his principality, but was initially unsuccessful. De Courcy's fortunes were boosted when Hugh de Lacy

(then Earl of Ulster

) and his associate William III de Briouze

, themselves fell foul of John; the king campaigned in Ireland against them in 1210, a campaign that forced de Briouze to return to Wales

and de Lacy to flee to St Andrews

in Scotland.

English records attest to Donnchadh's continued involvement in Ireland. One document, after describing how William de Briouze became the king's enemy in England and Ireland, records that after John arrived in Ireland in July 1210 : The Histoire des Ducs de Normandie recorded that William and Matilda had voyaged to the Isle of Man, en route from Ireland to Galloway, where they were captured. Matilda was imprisoned by the king, and died of starvation.

Another document, this one preserved in an Irish memoranda roll dating to the reign of King Henry VI

(reigned 1422–1461), records that after John's Irish expedition of 1210, Donnchadh controlled extensive territory in County Antrim

, namely the settlements of Larne

and Glenarm

with 50 carucate

s of land in between, a territory similar to the later barony of Glenarm Upper. King John had given or recognised Donnchadh's possession of this territory, and that of Donnchadh's nephew Alaxandair (Alexander), as a reward for his help; similarly, John had given Donnchadh's cousins Ailean and Tómas, sons of Lochlann, a huge lordship equivalent to 140 knight's fee

s that included most of northern County Antrim and County Londonderry

, the reward for use of their soldiers and galleys.

By 1219 however Donnchadh and his nephew appear to have lost all or most of his Irish land; a document of that year related that the Justiciar of Ireland, Geoffrey de Marisco, had dispossessed ("disseised") them believing they had conspired against the king in the rebellion of 1215–6. The king, John's successor Henry III

, found that this was not true and ordered the Justiciar to restore Donnchadh and his nephew to their lands. By 1224, Donnchadh had still not regained these lands and de Lacy's adherents were gaining more ground in the region. King Henry III repeated his earlier but ineffective instructions: he ordered Henry de Loundres

, Archbishop of Dublin

and new Justiciar of Ireland, to restore to Donnchadh "the remaining part of the land given to him by King John in Ireland, unless anyone held it by his father's own precept".

Later in the same year Donnchadh wrote to King Henry. His letter was as follows: Henry's response was a writ

to his Justiciar:

It is unlikely that Donnchadh ever regained his territory; after Hugh was formally restored to the Earldom of Ulster in 1227, Donnchadh's land was probably controlled by the Bisset family

. Historian Séan Duffy argues that the Bissets (later known as the "Bissets of the Glens

") helped Hugh de Lacy, and probably ended up with Donnchadh's territory as a reward.

Another of Donnchadh's sons, Eóin (John), owned the land of Straiton. He was involved in the Galwegian revolt of Gille-Ruadh

in 1235, during which he attacked some churches in the diocese of Glasgow. He received a pardon by granting patronage of the church of Straiton and the land of Hachinclohyn to William de Bondington

, Bishop of Glasgow, which was confirmed by Alexander II in 1244. Two other sons, Ailean (Alan) and Alaxandair (Alexander), are attested subscribing to Donnchadh and Cailean's charters to North Berwick. A Melrose charter mentions that Ailean was parson

of Kirchemanen. Cailean, and presumably Donnchadh's other legitimate sons, died before their father.

Donnchadh's probable grandson, Niall, was earl for only six years and died leaving no son but four daughters, one of whom is known by name. The last, presumably the eldest, was his successor Marjory, who married in turn Adam of Kilconquhar

(died 1271), a member of the Mac Duibh family of Fife, and Robert VI de Brus, Lord of Annandale

. Marjorie's son Robert VII de Brus, through military success and ancestral kinship with the Dunkeld dynasty, became King of the Scots as Robert I

. King Robert's brother, Edward Bruce

, became if only for a short time and only in name, High King of Ireland

.

Under the Bruces and their successors to the Scottish throne the title Earl of Carrick became a prestigious honorific title usually given to a son of the king or intended heir; at some time between 1250 and 1256 Earl Niall, anticipating that the earldom would be taken over by a man from another family, issued a charter to Lochlann (Roland) of Carrick, a son or grandson of one of Donnchadh's brothers. The charter granted Lochlann the title Cenn Cineoil, "head of the kindred", a position which brought the right to lead the men of Carrick in war. The charter also conferred possession of the office of baillie of Carrick under whoever was earl. Precedent had been established here by other native families of Scotland, something similar having already taken place in Fife; it was a way of ensuring that the kin-group retained strong locally-based male leadership even when the newly imposed common law of Scotland forced the comital title to pass into the hands of another family. By 1372 the office had passed—probably by marriage—to the Kennedy family of Dunure

.

The 17th-century genealogical compilation known as Ane Accompt of the Genealogie of the Campbells by Robert Duncanson, minister of Campbeltown

, claimed that "Efferic" (i.e. Affraic or Afraig), wife of Gilleasbaig of Menstrie

(fl.

1263–6) and mother of Campbell progenitor Cailean Mór

, was the daughter of one Cailean (anglicised Colin), "Lord of Carrick". Partly because Ane Accompt is a credible witness to much earlier material, the claim is thought probable. Thus Donnchadh was likely the great-grandfather of Cailean Mór, a lineage that explains the popularity of the names Donnchadh (Duncan) and Cailean (Colin) among later Campbells, as well as their close alliance to King Robert I during the Scottish Wars of Independence.

Anglicisation

Anglicisation, or anglicization , is the process of converting verbal or written elements of any other language into a form that is more comprehensible to an English speaker, or, more generally, of altering something such that it becomes English in form or character.The term most often refers to...

as Duncan) was a Gall-Gaidhil prince and Scottish

Kingdom of Scotland

The Kingdom of Scotland was a Sovereign state in North-West Europe that existed from 843 until 1707. It occupied the northern third of the island of Great Britain and shared a land border to the south with the Kingdom of England...

magnate in what is now south-western Scotland, whose career stretched from the last quarter of the 12th century until his death in 1250. His father, Gille-Brighde of Galloway, and his uncle, Uhtred of Galloway, were the two rival sons of Fergus

Fergus of Galloway

Fergus of Galloway was King, or Lord, of Galloway from an unknown date , until his death in 1161. He was the founder of that "sub-kingdom," the resurrector of the Bishopric of Whithorn, the patron of new abbeys , and much else besides...

, "King" or "Lord" of Galloway

Galloway

Galloway is an area in southwestern Scotland. It usually refers to the former counties of Wigtownshire and Kirkcudbrightshire...

. As a result of Gille-Brighde's conflict with Uhtred and the Scottish monarch William the Lion

William I of Scotland

William the Lion , sometimes styled William I, also known by the nickname Garbh, "the Rough", reigned as King of the Scots from 1165 to 1214...

, Donnchadh became a hostage of King Henry II of England

Henry II of England

Henry II ruled as King of England , Count of Anjou, Count of Maine, Duke of Normandy, Duke of Aquitaine, Duke of Gascony, Count of Nantes, Lord of Ireland and, at various times, controlled parts of Wales, Scotland and western France. Henry, the great-grandson of William the Conqueror, was the...

. He probably remained in England for almost a decade before returning north on the death of his father. Although denied succession to all the lands of the Gall-Gaidhil, he was granted lordship over Carrick

Carrick, Scotland

Carrick is a former comital district of Scotland which today forms part of South Ayrshire.-History:The word Carrick comes from the Gaelic word Carraig, meaning rock or rocky place. Maybole was the historic capital of Carrick. The county was eventually combined into Ayrshire which was divided...

in the north-west.

Little is known about Donnchadh's life and rule. Allied to John de Courcy

John de Courcy

John de Courcy was a Anglo-Norman knight who arrived in Ireland in 1176. From then until his expulsion in 1204, he conquered a considerable territory, endowed religious establishments, built abbeys for both the Benedictines and the Cistercians and built strongholds at Dundrum Castle in County...

, Donnchadh fought battles in Ireland and acquired land there that he subsequently lost. A patron of religious houses, particularly Melrose Abbey

Melrose Abbey

Melrose Abbey is a Gothic-style abbey in Melrose, Scotland. It was founded in 1136 by Cistercian monks, on the request of King David I of Scotland. It was headed by the Abbot or Commendator of Melrose. Today the abbey is maintained by Historic Scotland...

and North Berwick priory nunnery, he attempted to establish a monastery

Monastery

Monastery denotes the building, or complex of buildings, that houses a room reserved for prayer as well as the domestic quarters and workplace of monastics, whether monks or nuns, and whether living in community or alone .Monasteries may vary greatly in size – a small dwelling accommodating only...

in his own territory, at Crossraguel

Crossraguel Abbey

The Abbey of Saint Mary of Crossraguel is a ruin of a former abbey near the town of Maybole, South Ayrshire, Scotland.-Foundation:Founded in 1244 by Donnchadh, Earl of Carrick, following an earlier donation of 1225, to the monks of Paisley Abbey for that purpose. They reputedly built nothing more...

. He married the daughter of Alan fitz Walter, a leading member of the family later known as the House of Stewart—future monarchs of Scotland and England. Donnchadh was the first mormaer

Mormaer

The title of Mormaer designates a regional or provincial ruler in the medieval Kingdom of the Scots. In theory, although not always in practice, a Mormaer was second only to the King of Scots, and the senior of a toisech.-Origin:...

("earl

Earl

An earl is a member of the nobility. The title is Anglo-Saxon, akin to the Scandinavian form jarl, and meant "chieftain", particularly a chieftain set to rule a territory in a king's stead. In Scandinavia, it became obsolete in the Middle Ages and was replaced with duke...

") of Carrick, a region he ruled for more than six decades, making him one of the longest serving magnate

Magnate

Magnate, from the Late Latin magnas, a great man, itself from Latin magnus 'great', designates a noble or other man in a high social position, by birth, wealth or other qualities...

s in medieval Scotland

Scotland in the High Middle Ages

The High Middle Ages of Scotland encompass Scotland in the era between the death of Domnall II in 900 AD and the death of king Alexander III in 1286...

. His descendants include the Bruce and Stewart Kings of Scotland, and probably the Campbell

Clan Campbell

Clan Campbell is a Highland Scottish clan. Historically one of the largest, most powerful and most successful of the Highland clans, their lands were in Argyll and the chief of the clan became the Earl and later Duke of Argyll.-Origins:...

Dukes of Argyll

Duke of Argyll

Duke of Argyll is a title, created in the Peerage of Scotland in 1701 and in the Peerage of the United Kingdom in 1892. The Earls, Marquesses, and Dukes of Argyll were for several centuries among the most powerful, if not the most powerful, noble family in Scotland...

.

Sources

Donnchadh's career is not well documented in the surviving sources. CharterCharter

A charter is the grant of authority or rights, stating that the granter formally recognizes the prerogative of the recipient to exercise the rights specified...

s provide a little information about some of his activities, but overall their usefulness is limited; this is because no charter-collections (called cartularies) from the Gaelic south-west

Galwegian Gaelic

Galwegian Gaelic is an extinct dialect of Scottish Gaelic formerly spoken in southwest Scotland. It was spoken by the independent kings of Galloway in their time, and by the people of Galloway and Carrick until the early modern period. It was once spoken in Annandale and Strathnith...

have survived the Middle Ages, and the only surviving charters relevant to Donnchadh's career come from the heavily Normanised English-speaking area to the east. Principally, the relevant charters record his acts of patronage towards religious houses, but incidental details mentioned in the body of these texts and the witness lists subscribed to them are useful for other matters.

Some English government records describe his activities in relation to Ireland, and occasional chronicle

Chronicle

Generally a chronicle is a historical account of facts and events ranged in chronological order, as in a time line. Typically, equal weight is given for historically important events and local events, the purpose being the recording of events that occurred, seen from the perspective of the...

entries from England and the English-speaking regions of what became south-eastern Scotland record other important details. Aside from the Chronicle of Melrose

Chronicle of Melrose

The Chronicle of Melrose is a medieval chronicle from the Cottonian Manuscript, Faustina B. ix within the British Museum. It was written by unknown authors, though evidence in the writing shows that it most likely was written by the monks at Melrose Abbey. The chronicle begins on the year 735 and...

, the most significant of these sources are the works of Roger of Hoveden

Roger of Hoveden

Roger of Hoveden, or Howden , was a 12th-century English chronicler.From Hoveden's name and the internal evidence of his work, he is believed to have been a native of Howden in East Yorkshire. Nothing is known of him before the year 1174. He was then in attendance upon Henry II, by whom he was sent...

, and the material preserved in the writings of John of Fordun

John of Fordun

John of Fordun was a Scottish chronicler. It is generally stated that he was born at Fordoun, Mearns. It is certain that he was a secular priest, and that he composed his history in the latter part of the 14th century; and it is probable that he was a chaplain in the St Machar's Cathedral of...

and Walter Bower

Walter Bower

Walter Bower , Scottish chronicler, was born about 1385 at Haddington, East Lothian.He was abbot of Inchcolm Abbey from 1418, was one of the commissioners for the collection of the ransom of James I, King of Scots, in 1423 and 1424, and in 1433 one of the embassy to Paris on the business of the...

.

Roger of Hoveden wrote two important works: the Gesta Henrici II ("Deeds of Henry II", alternatively titled Gesta Henrici et Ricardi, "Deeds of Henry and Richard") and the Chronica, the latter a re-worked and supplemented version of the former. These works are the most important and valuable sources for Scottish history in the late 12th century. The Gesta Henrici II covers the period from 1169 to April 1192, and the Chronica covers events until 1201. Roger of Hoveden is particularly important in relation to what is now south-western Scotland, the land of the Gall-Gaidhil. He served as an emissary in the region in 1174 on behalf of the English monarch, and thus his account of, for example, the approach of Donnchadh's father Gille-Brighde towards the English king comes from a witness. Historians rely on Roger's writings for a number of important details about Donnchadh's life: that Gille-Brighde handed Donnchadh over as a hostage to Henry II

Henry II of England

Henry II ruled as King of England , Count of Anjou, Count of Maine, Duke of Normandy, Duke of Aquitaine, Duke of Gascony, Count of Nantes, Lord of Ireland and, at various times, controlled parts of Wales, Scotland and western France. Henry, the great-grandson of William the Conqueror, was the...

under the care of Hugh de Morwic, Sheriff of Cumberland; that Donnchcadh married the daughter of Alan fitz Walter under protest from the Scottish king; and that Donnchadh fought a battle in Ireland in 1197 assisting John de Courcy

John de Courcy

John de Courcy was a Anglo-Norman knight who arrived in Ireland in 1176. From then until his expulsion in 1204, he conquered a considerable territory, endowed religious establishments, built abbeys for both the Benedictines and the Cistercians and built strongholds at Dundrum Castle in County...

, Prince of Ulster.

Another important chronicle source is the material preserved in John of Fordun's Chronica gentis Scottorum ("Chronicle of the Scottish people") and Walter Bower's Scotichronicon

Scotichronicon

The Scotichronicon is a 15th-century chronicle or legendary account, by the Scottish historian Walter Bower. It is a continuation of historian-priest John of Fordun's earlier work Chronica Gentis Scotorum beginning with the founding of Scotland of mediaeval legend, by Scota with Goídel...

. John of Fordun's work, which survives on its own, was incorporated in the following century into the work of Bower. Fordun's Chronica was written and compiled between 1384 and August 1387. Despite the apparently late date, Scottish textual historian Dauvit Broun

Dauvit Broun

Dauvit Broun is a Scottish historian, Professor of Scottish History at the University of Glasgow. A specialist in medieval Scottish and Celtic studies, he concentrates primarily on early medieval Scotland, and has written abundantly on the topic of early Scottish king-lists, as well as on...

has shown that Fordun's work in fact consists of two earlier pieces, Gesta Annalia I and Gesta Annalia II, the former written before April 1285 and covering the period from King Máel Coluim mac Donnchada (Malcolm III, died 1093) to 2 February 1285. Gesta Annalia I appears to have been based on an even earlier text, about the descendants of Saint Margaret of Scotland

Saint Margaret of Scotland

Saint Margaret of Scotland , also known as Margaret of Wessex and Queen Margaret of Scotland, was an English princess of the House of Wessex. Born in exile in Hungary, she was the sister of Edgar Ætheling, the short-ruling and uncrowned Anglo-Saxon King of England...

, produced at Dunfermline Abbey

Dunfermline Abbey

Dunfermline Abbey is as a Church of Scotland Parish Church located in Dunfermline, Fife, Scotland. In 2002 the congregation had 806 members. The minister is the Reverend Alastair Jessamine...

. Thus material from these works concerning the late 12th and early 13th century Gall-Gaidhil may represent, despite the apparent late date, reliable contemporary or near-contemporary accounts.

Geographic and cultural background

River Forth

The River Forth , long, is the major river draining the eastern part of the central belt of Scotland.The Forth rises in Loch Ard in the Trossachs, a mountainous area some west of Stirling...

, a multi-ethnic region during the late 12th century. North of the Forth was the Gaelic kingdom of Scotland (Alba), which under its partially Normanised kings exercised direct or indirect control over most of the region to the south as far as the borders of Northumberland

Northumberland

Northumberland is the northernmost ceremonial county and a unitary district in North East England. For Eurostat purposes Northumberland is a NUTS 3 region and is one of three boroughs or unitary districts that comprise the "Northumberland and Tyne and Wear" NUTS 2 region...

and Cumberland

Cumberland

Cumberland is a historic county of North West England, on the border with Scotland, from the 12th century until 1974. It formed an administrative county from 1889 to 1974 and now forms part of Cumbria....

. Lothian

Lothian

Lothian forms a traditional region of Scotland, lying between the southern shore of the Firth of Forth and the Lammermuir Hills....

and the Merse were the heartlands of the northern part of the old English Earldom of Northumbria

Earl of Northumbria

Earl of Northumbria was a title in the Anglo-Danish, late Anglo-Saxon, and early Anglo-Norman period in England. The earldom of Northumbria was the successor of the ealdormanry of Bamburgh, itself the successor of an independent Bernicia. Under the Norse kingdom of York, there were earls of...

, and in the late 12th century the people of these regions, as well as the people of Lauderdale

Lauderdale

Lauderdale, denoting "dale of the river Leader", is the dale and region around that river in south-eastern Scotland.It can also refer to:-People:*Earls of Lauderdale*Lord Lauderdale, member of The Cabal of Charles II of England-Place names:Australia...

, Eskdale

Eskdale, Dumfries and Galloway

Eskdale is a glen in Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland. The River Esk flows through Eskdale to its estuary at the Solway Firth....

, Liddesdale

Liddesdale

Liddesdale, the valley of the Liddel Water, in the County of Roxburgh, southern Scotland, extends in a south-westerly direction from the vicinity of Peel Fell to the River Esk, a distance of...

, and most of Teviotdale and Annandale, were English in language and regarded themselves as English by ethnicity, despite having been under the control of the king of the Scots for at least a century.

Clydesdale

Clydesdale

Clydesdale was formerly one of nineteen local government districts in the Strathclyde region of Scotland.The district was formed by the Local Government Act 1973 from part of the former county of Lanarkshire: namely the burghs of Biggar and Lanark and the First, Second and Third Districts...

(or Strathclyde) was the heartland of the old Kingdom of Strathclyde

Kingdom of Strathclyde

Strathclyde , originally Brythonic Ystrad Clud, was one of the early medieval kingdoms of the celtic people called the Britons in the Hen Ogledd, the Brythonic-speaking parts of what is now southern Scotland and northern England. The kingdom developed during the post-Roman period...

; by Donnchadh's day the Scots had settled many English and Continental Europeans (principally Flemings) in the region, and administered it through the sheriffdom of Lanark. Gaelic too had penetrated much of the old Northumbrian and Strathclyde territory, coming from the west, south-west and the north, a situation that led historian Alex Woolf

Alex Woolf

Alex Woolf is a medieval historian based at the University of St Andrews. He specialises in the history of the British Isles and Scandinavia in the Early Middle Ages, especially in relation to the peoples of Wales and Scotland. He is author of volume two in the New Edinburgh History of Scotland,...

to compare the region to the Balkans. The British language

Brythonic languages

The Brythonic or Brittonic languages form one of the two branches of the Insular Celtic language family, the other being Goidelic. The name Brythonic was derived by Welsh Celticist John Rhys from the Welsh word Brython, meaning an indigenous Briton as opposed to an Anglo-Saxon or Gael...

of the area, as a result of such developments, was probably either dead or almost dead, perhaps surviving only in the uplands of Clydesdale, Tweeddale

Tweeddale

Tweeddale is a committee area and lieutenancy area in the Scottish Borders with a population of 17,394 at the latest census in 2001 it is the second smallest of the 5 committee areas in the Borders. It is the traditional name for the area drained by the upper reaches of the River Tweed...

and Annandale.

The rest of the region was settled by the people called Gall-Gaidhil (modern Scottish Gaelic: Gall-Ghàidheil) in their own language, variations of Gallwedienses in Latin

Medieval Latin

Medieval Latin was the form of Latin used in the Middle Ages, primarily as a medium of scholarly exchange and as the liturgical language of the medieval Roman Catholic Church, but also as a language of science, literature, law, and administration. Despite the clerical origin of many of its authors,...

, and normally Galwegians or Gallovidians in modern English. References in the 11th century to the kingdom of the Gall-Gaidhil centre it far to the north of what is now Galloway

Galloway

Galloway is an area in southwestern Scotland. It usually refers to the former counties of Wigtownshire and Kirkcudbrightshire...

. Kingarth

Kingarth

Kingarth is a historic village and parish on the Isle of Bute, off the coast of south-western Scotland. In the Early Middle Ages it was the site of a monastery and bishopric and the cult centre of Saints Cathan and Bláán ....

(Cenn Garadh) and Eigg

Eigg

Eigg is one of the Small Isles, in the Scottish Inner Hebrides. It lies to the south of the Skye and to the north of the Ardnamurchan peninsula. Eigg is long from north to south, and east to west. With an area of , it is the second largest of the Small Isles after Rùm.-Geography:The main...

(Eic) were described as "in Galloway" (Gallgaidelaib) by the Martyrology of Óengus, in contrast to Whithorn

Whithorn

Whithorn is a former royal burgh in Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland, about ten miles south of Wigtown. The town was the location of the first recorded Christian church in Scotland, Candida Casa : the 'White [or 'Shining'] House', built by Saint Ninian about 397.-Eighth and twelfth centuries:A...

—part of modern Galloway—which was named as lying within another kingdom, The Rhinns

Kingdom of the Rhinns

Na Renna, or the Kingdom of the Rhinns, was a Norse-Gaelic lordship which appears in the 11th century records. The Rhinns was a province in medieval Scotland, and comprised, along with Farines, the later county of Wigtown...

(Na Renna). These areas had been part of the Kingdom of Northumbria until the 9th century, and afterward were transformed by a process very poorly documented, but probably carried out by numerous small bands of culturally Scandinavian but linguistically Gaelic warrior-settlers moving in from Ireland and southern Argyll. "Galloway" today only refers to the lands of Rhinns, Farines, Glenken, Desnes Mór and Desnes Ioan (that is, Wigtownshire

Wigtownshire

Wigtownshire or the County of Wigtown is a registration county in the Southern Uplands of south west Scotland. Until 1975, the county was one of the administrative counties used for local government purposes, and is now administered as part of the council area of Dumfries and Galloway...

and the Stewartry of Kirkcudbright), but this is due to the territorial changes that took place in and around Donnchadh's lifetime rather than being the contemporary definition. For instance, a 12th century piece of marginalia

Marginalia

Marginalia are scribbles, comments, and illuminations in the margins of a book.- Biblical manuscripts :Biblical manuscripts have liturgical notes at the margin, for liturgical use. Numbers of texts' divisions are given at the margin...

located the island of Ailsa Craig

Ailsa Craig

Ailsa Craig is an island of 219.69 acres in the outer Firth of Clyde, Scotland where blue hone granite was quarried to make curling stones. "Ailsa" is pronounced "ale-sa", with the first syllable stressed...

"lying between Gallgaedelu [Galloway] and Cend Tiri [Kintyre]", while a charter of Máel Coluim IV ("Malcolm IV") describes Strathgryfe

Strathgryfe

Strathgryffe or Gryffe Valley is a strath or wide valley centred on the River Gryffe in the west central Lowlands of Scotland....

, Cunningham

Cunninghame

Cunninghame is a former comital district of Scotland and also a district of the Strathclyde Region from 1975–1996.-Historic Cunninghame:The historic district of Cunninghame was bordered by the districts of Renfrew and Clydesdale to the north and east respectively, by the district of Kyle to the...

, Kyle

Kyle, Ayrshire

Kyle is a former comital district of Scotland which stretched across parts of modern day East Ayrshire and South Ayrshire...

and Carrick as the four cadrez (probably from ceathramh, "quarter"s) of Galloway; an Irish annal entry for the year 1154 designated galleys from Arran

Isle of Arran

Arran or the Isle of Arran is the largest island in the Firth of Clyde, Scotland, and with an area of is the seventh largest Scottish island. It is in the unitary council area of North Ayrshire and the 2001 census had a resident population of 5,058...

, Kintyre, the Isle of Man as Gallghaoidhel, "Galwegian".

By the middle of the 12th century the former territory of the kingdom of the Rhinns was part of Galloway kingdom, but the area to the north was not. Strathgryfe, Kyle and Cunningham had come under the control of the Scottish king in the early 12th century, much of it given over to soldiers of French or Anglo-French origin. Strathgryfe and most of Kyle had been given to Walter fitz Alan under King David I

David I of Scotland

David I or Dabíd mac Maíl Choluim was a 12th-century ruler who was Prince of the Cumbrians and later King of the Scots...

, with Hugh de Morville

Hugh de Morville, Lord of Cunningham and Lauderdale

Hugh de Morville was a Norman knight who made his fortune in the service of David fitz Malcolm, Prince of the Cumbrians and King of Scots .His parentage is said by some to be unclear, but G. W. S...

taking Cunningham. Strathnith still had a Gaelic ruler (ancestor of the famous Thomas Randolph, 1st Earl of Moray), but he was not part of the kingdom of Galloway. The rest of the region—the Rhinns, Farines, Carrick, Desnes Mór and Desnes Ioan, and the sparsely settled uplands of Glenken—was probably under the control of the sons of Fergus

Fergus of Galloway

Fergus of Galloway was King, or Lord, of Galloway from an unknown date , until his death in 1161. He was the founder of that "sub-kingdom," the resurrector of the Bishopric of Whithorn, the patron of new abbeys , and much else besides...

, King of Galloway, in the years before Donnchadh's career in the region.

Origins and family

Donnchadh was the son of Gille-Brighde, son of Fergus, king of the Gall-Gaidhil. Donnchadh's ancestry cannot be traced further; no patronymic is known for Fergus from contemporary sources, and when Fergus' successors enumerate their ancestors in documents, they never go earlier than he does. The name Gille-Brighde, used by Donnchadh's father (Fergus' son), was also the name of the father of SomhairleSomerled

Somerled was a military and political leader of the Scottish Isles in the 12th century who was known in Gaelic as rí Innse Gall . His father was Gillebride...

, petty king of Argyll

Lord of Argyll

The sovereign or feudal lordship of Argyle was the holding of the senior branch of descendants of king Somhairle, this branch becoming soon known as Clan MacDougallConstruction of the Lordship of Argyll-Lorne essentially started with Donnchad mac Dubgaill....

in the third quarter of the 12th century. As the original territory of the Gall-Gaidhil kingdom probably adjoined or included Argyll, Alex Woolf has suggested that Fergus and Somhairle were brothers or cousins.

There is a "body of circumstantial evidence" that suggests Donnchadh's mother was a daughter or sister of Donnchadh II, Earl of Fife. This includes Donnchadh's association with the Cistercian nunnery of North Berwick, founded by Donnchadh II of Fife's father, Donnchadh I of Fife

Donnchad I, Earl of Fife

Mormaer Donnchad I , anglicized as Duncan or Dunecan, was the first Gaelic magnate to have his territory regranted to him by feudal charter, by David I in 1136. Donnchad I, as head of the native Scottish nobility, had the job of introducing and conducting King Máel Coluim IV around the Kingdom upon...

; close ties seem to have existed between the two families, while Donnchadh's own name is further evidence. The historian who suggested this in 2000, Richard Oram

Richard Oram

Professor Richard D. Oram F.S.A. is a Scottish historian. He is a Professor of Medieval and Environmental History at the University of Stirling and an Honorary Lecturer in History at the University of Aberdeen. He is also the director of the Centre for Environmental History and Policy at the...

, came to regard this conjecture as certain by 2004.

Henry I of England

Henry I was the fourth son of William I of England. He succeeded his elder brother William II as King of England in 1100 and defeated his eldest brother, Robert Curthose, to become Duke of Normandy in 1106...

; that is, Uhtred and his descendants were related to the English royal family, while Gille-Brighde and his descendants were not. However, according to historian G. W. S. Barrow

G. W. S. Barrow

Geoffrey Wallis Steuart Barrow DLitt FBA FRSE is a British historian and academic. He is Professor Emeritus at the University of Edinburgh, and arguably the most prominent Scottish medievalist of the last century....

, the theory is disproved by one English royal document, written in the name of King John of England

John of England

John , also known as John Lackland , was King of England from 6 April 1199 until his death...

, which likewise asserts that Donnchadh was John's cousin.

It is unclear how many siblings Donnchadh had, but two at least are known. The first, Máel Coluim, led the forces that besieged Gille-Brighde's brother Uhtred on "Dee island" (probably Threave) in Galloway in 1174. This Máel Coluim captured Uhtred, who subsequently, in addition to being blinded and castrated, had his tongue cut out. Nothing more is known of Máel Coluim's life; there is speculation by some modern historians that he was illegitimate. Another brother appears in the records of Paisley Abbey

Paisley Abbey

Paisley Abbey is a former Cluniac monastery, and current Church of Scotland parish kirk, located on the east bank of the White Cart Water in the centre of the town of Paisley, Renfrewshire, in west central Scotland.-History:...

. In 1233, one Gille-Chonaill Manntach, "the Stammerer" (recorded Gillokonel Manthac), gave evidence regarding a land dispute in Strathclyde; the document described him as the brother of the Earl of Carrick, who at that time was Donnchadh.

Exile and return

In 1160, Máel Coluim mac Eanric (Malcolm IV), king of the Scots, forced Fergus into retirement, and brought Galloway under his overlordship. It is likely that from 1161 until 1174, Fergus' sons Gille-Brighde and Uhtred shared the lordship of the Gall-Gaidhil under the Scottish king's authority, with Gille-Brighde in the west and Uhtred in the east. When in 1174 the Scottish king William the Lion was captured during an invasion of England, the brothers responded by rebelling against the Scottish monarch. Subsequently, they fought each other, with Donnchadh's father ultimately prevailing.Having defeated his brother, Gille-Brighde unsuccessfully sought to become a direct vassal of Henry II, king of England. An agreement was obtained with Henry in 1176, Gille-Brighde promising to pay him 1000 mark

Mark (money)

Mark was a measure of weight mainly for gold and silver, commonly used throughout western Europe and often equivalent to 8 ounces. Considerable variations, however, occurred throughout the Middle Ages Mark (from a merging of three Teutonic/Germanic languages words, Latinized in 9th century...

s of silver and handing over his son Donnchadh as a hostage. Donnchadh was taken into the care of Hugh de Morwic, sheriff of Cumberland

Cumberland

Cumberland is a historic county of North West England, on the border with Scotland, from the 12th century until 1974. It formed an administrative county from 1889 to 1974 and now forms part of Cumbria....

. The agreement seems to have included recognising Donnchadh's right to inherit Gille-Brighde's lands, for nine years later, in the aftermath of Gille-Brighde's death, when Uhtred's son Lochlann (Roland) invaded western Galloway, Roger of Hoveden described the action as "contrary to [Henry's] prohibition".

The activities of Donnchadh's father Gille-Brighde after 1176 are unclear, but some time before 1184 King William raised an army to punish Gille-Brighde "and the other Galwegians who had wasted his land and slain his vassals"; he held off the endeavour, probably because he was worried about the response of Gille-Brighde's protector Henry II. There were raids on William's territory until Gille-Brighde's death in 1185. The death of Gille-Brighde prompted Donnchadh's cousin Lochlann, supported by the Scottish king, to attempt a takeover, thus threatening Donnchadh's inheritance. At that time Donnchadh was still a hostage in the care of Hugh de Morwic.

The Gesta Annalia I claimed that Donnchadh's patrimony was defended by chieftains called Somhairle ("Samuel"), Gille-Patraic, and Eanric Mac Cennetig ("Henry Mac Kennedy"). Lochlann and his army met these men in battle on 4 July 1185 and, according to the Chronicle of Melrose, killed Gille-Patraic and a substantial number of his warriors. Another battle took place on 30 September, and although Lochlann's forces were probably victorious, killing opponent leader Gille-Coluim, the encounter led to the death of Lochlann's unnamed brother. Lochlann's activities provoked a response from King Henry who, according to historian Richard Oram

Richard Oram

Professor Richard D. Oram F.S.A. is a Scottish historian. He is a Professor of Medieval and Environmental History at the University of Stirling and an Honorary Lecturer in History at the University of Aberdeen. He is also the director of the Centre for Environmental History and Policy at the...

, "was not prepared to accept a fait accompli that disinherited the son of a useful vassal, flew in the face of the settlement which he had imposed ... and deprived him of influence over a vitally strategic zone on the north-west periphery of his realm".

According to Hoveden, in May 1186 Henry ordered the king and magnates of Scotland to subdue Lochlann; in response Lochlann "collected numerous horse and foot and obstructed the entrances to Galloway and its roads to what extent he could". Richard Oram did not believe that the Scots really intended to do this, as Lochlann was their dependent and probably acted with their consent; this, Oram argued, explains why Henry himself raised an army and marched north to Carlisle. When Henry arrived he instructed King William and his brother David, Earl of Huntingdon, to come to Carlisle, and to bring Lochlann with them.

Lochlann ignored Henry's summons until an embassy consisting of Hugh de Puiset

Hugh de Puiset

Hugh de Puiset was a medieval Bishop of Durham and Chief Justiciar of England under King Richard I. He was the nephew of King Stephen of England and Henry of Blois, who both assisted Hugh's ecclesiastical career...

, Bishop of Durham and Justiciar Ranulf de Glanville provided him with hostages as a guarantee of his safety; when he agreed to travel to Carlisle with the king's ambassadors. Hoveden wrote that Lochlann was allowed to keep the land that his father Uhtred had held "on the day he was alive and dead", but that the land of Gille-Brighde that was claimed by Donnchadh, son of Gille-Brighde, would be settled in Henry's court, to which Lochlann would be summoned. Lochlann agreed to these terms. King William and Earl David swore an oath to enforce the agreement, with Jocelin, Bishop of Glasgow, instructed to excommunicate any party that should breach their oath.

Ruler of Carrick

There is no record of any subsequent court hearing, but the Gesta Annalia I relates that Donnchadh was granted Carrick on condition of peace with Lochlann, and emphasises the role of King William (as opposed to Henry) in resolving the conflict. Richard Oram has pointed out that Donnchadh's grant to Melrose Abbey between 1189 and 1198 was witnessed by his cousin Lochlann, evidence perhaps that relations between the two had become more cordial. Although no details are given any contemporary source, Donnchadh gained possession of some of his father's land in the west of the kingdom of Gall-Gaidhil, namely the "earldom" of Carrick.When Donnchadh adopted or was given the title of "earl" (Latin: comes), or in his own language mormaer, is a debated question. Historian Alan Orr Anderson

Alan Orr Anderson

Alan Orr Anderson was a Scottish historian and compiler. He graduated from the University of Edinburgh. The son of Rev. John Anderson and Ann Masson, he was born in 1879...

argued that he began using the title of comes between 1214 and 1216, based on Donnchadh's appearance as a witness to two charters issued by Thomas de Colville; the first, known as Melrose 193 (this being its number in Cosmo Innes

Cosmo Innes

Cosmo Nelson Innes was a Scottish historian and antiquary.Innes was educated at Edinburgh High School, at Aberdeen and Glasgow Universities, and at Balliol College, Oxford. He was admitted to the Faculty of Advocates in 1822, and was appointed Professor of Constitutional Law and History in the...

's printed version of the cartulary), was dated by Anderson to 1214. In this charter, Donnchadh has no title. By contrast Donnchadh was styled comes in a charter dated by Anderson to 1216, Melrose 192.

Oram however pointed out that Donnchadh was styled comes in a grant to Melrose Abbey witnessed by Richard de Morville (Melrose 32), who died in 1196. If the wording in this charter is accurate, then Donnchadh was using the title before Richard's death: that is, in or before 1196. Furthermore, while Anderson dated Melrose 192 with reference to Abbot William III de Courcy (abbot of Melrose from 1215 to 1216), Oram identified Abbot William as Abbot William II (abbot from 1202 to 1206). Whenever Donnchadh adopted the title, he is the first known "earl" of the region.

Firth of Clyde

The Firth of Clyde forms a large area of coastal water, sheltered from the Atlantic Ocean by the Kintyre peninsula which encloses the outer firth in Argyll and Ayrshire, Scotland. The Kilbrannan Sound is a large arm of the Firth of Clyde, separating the Kintyre Peninsula from the Isle of Arran.At...

, in the Irish Sea

Irish Sea

The Irish Sea separates the islands of Ireland and Great Britain. It is connected to the Celtic Sea in the south by St George's Channel, and to the Atlantic Ocean in the north by the North Channel. Anglesey is the largest island within the Irish Sea, followed by the Isle of Man...

region far from the main centres of Scottish and Anglo-Norman influence lying to its east and south-east. Carrick was separated from Kyle in the north and north-east by the river Doon

River Doon

The River Doon is a river in South Ayrshire, Scotland. The river flows 23 miles from Loch Doon, joining the Firth of Clyde just south of Ayr. Its course is generally north-westerly, passing near to the town of Dalmellington, and through the villages of Patna, Dalrymple, and Alloway, birthplace...

, and from Galloway-proper by Glenapp and by the adjacent hills and forests. There were three main rivers, the Doon, the Girvan and the Stinchar

River Stinchar

The River Stinchar is a river in South Ayrshire, Scotland. It flows south west from the Galloway Forest Park to enter the Firth of Clyde at Ballantrae, about south south east of Ailsa Craig....

, though most of the province was hilly, meaning that most wealth came from animal husbandry

Animal husbandry

Animal husbandry is the agricultural practice of breeding and raising livestock.- History :Animal husbandry has been practiced for thousands of years, since the first domestication of animals....

rather than arable farming

Arable land

In geography and agriculture, arable land is land that can be used for growing crops. It includes all land under temporary crops , temporary meadows for mowing or pasture, land under market and kitchen gardens and land temporarily fallow...

. The population of Carrick, like that in neighbouring Galloway, consisted of kin-groups governed by a "chief" or "captain" (cenn, Latin capitaneus). Above these captains was the Cenn Cineoil ("kenkynolle"), the "kin-captain" of Carrick, a position held by the mormaer; it was not until after Donnchadh's death that these two positions were separated. The best recorded groups are Donnchadh's own group (known only as de Carrick, "of Carrick") and the Mac Cennétig (Kennedy) family

Clan Kennedy

Clan Kennedy is a Scottish clan and an Irish surname.-Origins:The Kennedys had their home territory in Carrick in Ayrshire, in southwestern Scotland. Originally they were of Pictish/Norse stock from the Western Isles. In the fifteenth century, one Ulric Kennedy fled Ayrshire to Lochaber in the...

, who seem to have provided the earldom's hereditary stewards.

The population was governed under these leaders by a customary law that remained distinct from the common law of Scotland for the remainder of the Middle Ages. One documented aspect of Carrick and Galloway law was the power of sergeants (an original Gaelic word Latinised as Kethres), officials of the earl or of other captains, to claim one night of free hospitality (a privilege called sorryn et frithalos), and to accuse and arrest with little restriction. The personal demesne

Demesne

In the feudal system the demesne was all the land, not necessarily all contiguous to the manor house, which was retained by a lord of the manor for his own use and support, under his own management, as distinguished from land sub-enfeoffed by him to others as sub-tenants...

, or lands, of the earl was probably extensive in Donnchadh's time; in 1260, during the minority of Donnchadh's descendant Countess Marjory of Carrick, an assessment made by the Scottish king showed that the earls had estates throughout the province, in upland locations like Straiton

Straiton

Straiton is a village on the River Girvan in South Ayrshire in Scotland, mainly built in the 18th century, but with some recent housing.It was the main location for the film The Match, where two rival pubs played an annual football match as a challenge...

, Glengennet and Bennan, as well as in the east in locations such as Turnberry

Turnberry Castle

Turnberry Castle is a fragmentary ruin on the coast of Kirkoswald parish, north of Girvan in Ayrshire, Scotland. It is situated on a rock at the extremity of the lower peninsula within the parish.-History:...

and Dalquharran.

Relations with the church

Records exist for Donnchadh's religious patronage, and these records provide evidence for Donnchadh's associates as well as the earl himself. Around 1200 Earl Donnchadh allowed the monks of Melrose AbbeyMelrose Abbey

Melrose Abbey is a Gothic-style abbey in Melrose, Scotland. It was founded in 1136 by Cistercian monks, on the request of King David I of Scotland. It was headed by the Abbot or Commendator of Melrose. Today the abbey is maintained by Historic Scotland...

use of saltpan

Salt evaporation pond

Salt evaporation ponds, also called salterns or salt pans, are shallow artificial ponds designed to produce salts from sea water or other brines. The seawater or brine is fed into large ponds and water is drawn out through natural evaporation which allows the salt to be subsequently harvested...

s from his land at Turnberry. Between 1189 and 1198 he had granted the church of Maybothelbeg ("Little Maybole

Maybole

Maybole is a burgh of barony and police burgh of South Ayrshire, Scotland. Pop. 4,552. It is situated south of Ayr and southwest of Glasgow by the Glasgow and South Western Railway. ...

") and the lands of Beath (Bethóc) to this Cistercian house. The grant is mentioned by the Chronicle of Melrose, under the year 1193: These estates were very rich, and became attached to Melrose's "super-grange" at Mauchline

Mauchline

Mauchline is a town in East Ayrshire, Scotland. In the 2001 census it had a recorded population of 4105. It lies by the Glasgow and South Western Railway line, 8 miles east-southeast of Kilmarnock and 11 miles northeast of Ayr. It is situated on a gentle slope about 1 mile from the River Ayr,...

in Kyle. In 1285 Melrose Abbey was able to persuade the earl of the time to force its tenants in Carrick to use the lex Anglicana (the "English law").

Witness to both grants were some prominent churchman connected with Melrose: magnates like Earl Donnchadh II of Fife, the latter's son Máel Coluim

Maol Choluim I, Earl of Fife

Mormaer Máel Coluim of Fife , or Maol Choluim anglicised as Malcolm, was one of the more obscure mormaers of Fife.He married Matilda, the daughter of Gille Brigte, the mormaer of Strathearn. He is credited with the foundation of Culross Abbey...

, Gille Brigte, Earl of Strathearn

Gille Brigte, Earl of Strathearn

Gille Brigte of Strathearn is the third known Mormaer of Strathearn. He is one of the most famous of the Strathearn mormaers. He succeeded his father Ferchar in 1171. He is often known by the Francization of his name, Gilbert, or by various anglicizations, such as Gilbride, Gilbridge, etc...

, as well as probable members of Donnchadh's retinue, like Gille-Osald mac Gille-Anndrais, Gille-nan-Náemh mac Cholmain, Gille-Chríst Bretnach ("the Briton"), and Donnchadh's chamberlain

Chamberlain (office)

A chamberlain is an officer in charge of managing a household. In many countries there are ceremonial posts associated with the household of the sovereign....

Étgar mac Muireadhaich. Áedh son of the mormaer of Lennox also witnessed these grants, and sometime between 1208 and 1214 Donnchadh (as "Lord Donnchadh") subscribed (i.e. his name was written at the bottom, as a "witness" to) a charter of Maol Domhnaich, Earl of Lennox

Maol Domhnaich, Earl of Lennox

Mormaer Maol Domhnaich was the son of Mormaer Ailín II, and ruled Lennox 1217–1250.Like his predecessor Ailín II, he showed absolutely no interest in extending an inviting hand to oncoming French or English settlers...

, son and heir of Mormaer Ailean II

Ailín II, Earl of Lennox

Mormaer Ailín II of Lennox, also known as Ailean or Alwyn, was the son of Mormaer Ailín I, and ruled Lennox from somewhere in the beginning of the 13th century until his death in 1217....

, to the bishopric of Glasgow regarding the church of Campsie

Campsie, Stirlingshire

Campsie is a hilly district in Stirlingshire, Scotland. It is noted for the beauty of Campsie Glen and the grandeur of the mountains known as the Campsie Fells.-See also:* Milton of Campsie* Campsie Fells* Clachan of Campsie...

.