Cherokee removal

Encyclopedia

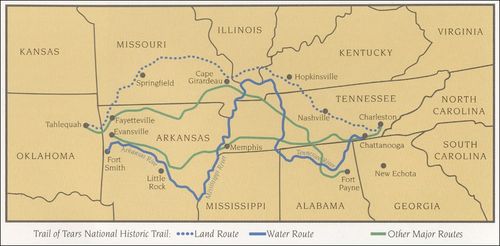

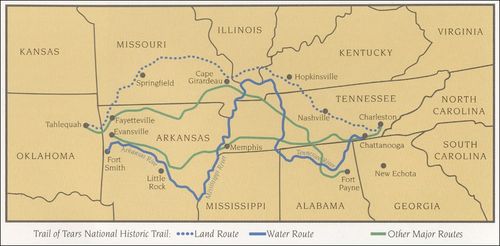

Cherokee removal, part of the Trail of Tears

, refers to the forced relocation

between 1836 to 1839 of the Cherokee

Nation from their lands in Georgia

, Texas

, Tennessee

, Alabama

, and North Carolina

to the Indian Territory

(present day Oklahoma

) in the Western United States

, which resulted in the deaths of approximately 4,000 Cherokees.

In the Cherokee language

, the event is called Nu na da ul tsun yi (the place where they cried), another term is Tlo va sa (our removal). However, this phrase was not used by Cherokees at the time, and seems to be of Choctaw

origin. The Cherokees were not the only American Indian

s to emigrate as a result of the Indian Removal

efforts. American Indians were not only removed from the American South

but also from the North

, Midwest

, Southwest

, and Plains

regions. The Choctaws, Chickasaw

s, and Creek Indians (Muskogee) emigrated reluctantly. The Seminole

s in Florida

resisted removal by guerrilla warfare

with the United States Army

for decades (1817–1850). Ultimately, some Seminoles remained in their Florida home country, while others were transported to Indian Territory in shackles. In contrast, the Cherokees resisted removal by hiring lawyers (see Worcester v. Georgia

).

The phrase, “Trail of Tears”, is used to refer to similar events endured by other Indian people, especially among the Five Civilized Tribes

. The phrase originated as a description of the voluntary removal of the Choctaw nation

in 1831.

In the fall of 1835, a census was taken by civilian officials of the US War Department to enumerate Cherokees residing in Alabama, Georgia, North Carolina, and Tennessee, with a count of 16,542 Cherokees, 201 inter-married whites, and 1592 slaves (total: 18,335 people). In October of that year Principal Chief John Ross

and an Eastern visitor, John Howard Payne

were kidnapped from Ross' Tennessee home by a renegade group of the Georgia militia

. Released, Ross and a delegation of tribal leaders travelled to Washington, DC to protest this high-handed action, and to lobby against the removal policy of President Andrew Jackson

. In this power vacuum, U.S. Agent John F. Schermerhorn

gathered a group of dissident Cherokees in the home of Elias Boudinot

at the tribal capitol, New Echota

, Georgia. There on December 29, 1835, this rump group signed the unauthorized Treaty of New Echota

, which exchanged Cherokee land in the East for lands west of the Mississippi River

in Indian Territory. This agreement was never accepted by the elected tribal leadership or a majority of the Cherokee people. In February, 1836 two Councils convened at Red Clay, Tennessee and at Valley Town, North Carolina (now Murphy, NC) and produced two lists totaling some 13,000 names written in the Sequoyah

writing script of Cherokees opposed to the Treaty. The lists were dispatched to Washington, DC and presented by Chief Ross to Congress. Nevertheless, a slightly modified version of the Treaty, was ratified by the U.S. Senate by a single vote on May 23, 1836, and signed into law by President

Jackson. The Treaty provided a grace period until May 1838 for the tribe to voluntarily remove themselves to Indian Territory.

, in 1828, resulting in the Georgia Gold Rush

, the first gold rush

in U.S. history. Hopeful gold speculators began trespassing on Cherokee lands, and pressure began to mount on the Georgia government to fulfill the promises of the Compact of 1802

.

When Georgia moved to extend state laws over Cherokee tribal lands in 1830, the matter went to the U.S. Supreme Court

. In Cherokee Nation v. Georgia

(1831), the Marshall court

ruled that the Cherokees were not a sovereign and independent nation, and therefore refused to hear the case. However, in Worcester v. State of Georgia (1832), the Court ruled that Georgia could not impose laws in Cherokee territory, since only the national government — not state governments — had authority in Indian affairs.

President Andrew Jackson

has often been quoted as defying the Supreme Court with the words: “John Marshall has made his decision; now let him enforce it!” Jackson probably never said this, but he was fully committed to the policy. He had no desire to use the power of the national government to protect the Cherokees from Georgia, since he was already entangled with states’ rights

issues in what became known as the nullification crisis

. With the Indian Removal Act

of 1830, the U.S. Congress

had given Jackson authority to negotiate removal treaties, exchanging Indian land in the East for land west of the Mississippi River. Jackson used the dispute with Georgia to put pressure on the Cherokees to sign a removal treaty.

With the Compact of 1802

, the state of Georgia

relinquished to the national government its western land claims (which became the states of Alabama

and Mississippi

). In exchange, the national government promised to eventually conduct treaties to relocate those Indian tribes living within Georgia, thus giving Georgia control of all land within its borders.

However, the Cherokees, whose ancestral tribal lands overlapped the boundaries of Georgia, Tennessee

, North Carolina

, and Alabama, declined to move. They established a capital in 1825 at New Echota

(near present-day Calhoun, Georgia

). Furthermore, led by principal Chief John Ross

and Major Ridge

, the speaker of the Cherokee National Council, the Cherokees adopted a written constitution on 26 July 1827, declaring the Cherokee Nation to be a sovereign and independent nation.

The Cherokee land that was lost proved to be extremely valuable. Upon these lands were the alignments for the future rights-of-way for rail and road communications between the eastern Piedmont slopes of the Appalachian Mountains, the Ohio river in Kentucky and the Tennessee river valley at Chattanooga

. This location is still a strategic economic asset and is the basis for the tremendous success of Atlanta, Georgia

, as a regional transportation and logistics center. Georgia’s appropriation of these lands from the Cherokee kept the wealth out of the hands of the Cherokee Nation.

The Cherokee lands in Georgia were settled upon by the Cherokee for the simple reason that they were and still are the shortest and most easily traversed route between the only fresh water sourced settlement location at the southeastern tip of the Appalachian range (the Chattahoochee River), and the natural passes, ridges, and valleys which lead to the Tennessee river at what is today, Chattanooga. From Chattanooga there was and is the potential for a year-round water transport to St. Louis and the west (via the Ohio and Mississippi rivers), or to as far east as Pittsburgh, PA.

With the landslide reelection of Andrew Jackson in 1832, some of the most strident Cherokee opponents of removal began to rethink their positions. Led by Major Ridge

With the landslide reelection of Andrew Jackson in 1832, some of the most strident Cherokee opponents of removal began to rethink their positions. Led by Major Ridge

, his son John Ridge

, and nephews Elias Boudinot

and Stand Watie

, they became known as the “Ridge Party”, or the “Treaty Party”. The Ridge Party believed that it was in the best interest of the Cherokees to get favorable terms from the U.S. government, before white squatters, state governments, and violence made matters worse. John Ridge began unauthorized talks with the Jackson administration in the late 1820s. Meanwhile, in anticipation of the Cherokee removal, the state of Georgia began holding lotteries

in order to divide up the Cherokee tribal lands among white Georgians.

However, Principal Chief John Ross

and the majority of the Cherokee people remained adamantly opposed to removal. Political maneuvering began: Chief Ross canceled the tribal elections in 1832, the Council threatened to impeach the Ridges, and a prominent member of the Treaty Party (John Walker, Jr.) was murdered. The Ridges responded by eventually forming their own council, representing only a fraction of the Cherokee people. This split the Cherokee Nation into two factions: those following Ross, known as the National Party, and those of the Treaty Party, who elected

William A. Hicks

, who had briefly succeeded his brother Charles R. Hicks

as Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation to act as titular leader of the pro-Treaty faction, with former National Council clerk Alexander McCoy as his assistant.

In 1835, Jackson appointed Reverend John F. Schermerhorn

as a treaty commissioner. The U.S. government proposed to pay the Cherokee Nation US$4.5 million (among other considerations) to remove themselves. These terms were rejected in October 1835 by the Cherokee Nation Council meeting at Red Clay

. Chief Ross, attempting to bridge the gap between his administration and the Ridge Party, traveled to Washington with a party that included John Ridge and Stand Watie to open new negotiations, but they were turned away and told to deal with Schermerhoerne.

Meanwhile, Schermerhorn organized a meeting with the pro-removal council members at New Echota

, Georgia

. Only five hundred Cherokees (out of thousands) responded to the summons, and, on December 30, 1835, twenty-one proponents of Cherokee removal (Major Ridge, Elias Boudinot, James Foster, Testaesky, Charles Moore, George Chambers, Tahyeske, Archilla Smith, Andrew Ross (younger brother of Chief John Ross), William Lassley, Caetehee, Tegaheske, Robert Rogers, John Gunter, John A. Bell, Charles Foreman, William Rogers, George W. Adair, James Starr, and Jesse Halfbreed), signed or left “X” marks on the Treaty of New Echota

after those present voted unanimously for its approval. John Ridge and Stand Watie signed the treaty when it was brought to Washington. Chief Ross, as expected, refused.

This treaty gave up all the Cherokee land east of the Mississippi

in return for five million dollars to be disbursed on a per capita

basis, an additional half-million dollars for educational funds, title in perpetuity to an amount of land in Indian Territory equal to that given up, and full compensation for all property left in the East. There was also a clause in the treaty as signed allowing Cherokee who so desired to remain and become citizens of the states in which they resided on 160 acre (0.6474976 km²) of land, but that was later stricken out by President Jackson.

Despite the protests by the Cherokee National Council and principal Chief Ross that the document was a fraud, Congress ratified the treaty on May 23, 1836, by just one vote.

There are muster rolls for groups # 1, 3 – 6 and daily journals of conductors for groups # 2 and 5 among records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs in the National Archives. Despite the government blandishments, only a few hundred volunteered to accept the Treaty terms for Removal.

Many white Americans were outraged by the dubious legality of the treaty and called on the government not to force the Cherokees to move. For example, on April 23, 1838, Ralph Waldo Emerson

Many white Americans were outraged by the dubious legality of the treaty and called on the government not to force the Cherokees to move. For example, on April 23, 1838, Ralph Waldo Emerson

wrote a letter to Jackson’s successor, President Martin Van Buren

, urging him not to inflict “so vast an outrage upon the Cherokee Nation.”

Nevertheless, as the May 23, 1838, deadline for voluntary removal approached, President Van Buren assigned General Winfield Scott

to head the forcible removal operation. He arrived at New Echota on May 17, 1838, in command of U.S. Army and state militia totalling about 7,000 soldiers. They began rounding up Cherokees in Georgia on May 26, 1838; ten days later, operations began in Tennessee, North Carolina, and Alabama. Men, women, and children were removed at gunpoint from their homes over three weeks and gathered together in camps, often with very few of their possessions. Another soldier, Private John G. Burnett later wrote "Future generations will read and condemn the act and I do hope posterity will remember that private soldiers like myself, and like the four Cherokees who were forced by General Scott to shoot an Indian Chief and his children, had to execute the orders of our superiors. We had no choice in the matter."

This story is perhaps a garbled version of the episode when a Cherokee named Tsali

or Charley and three others killed two soldiers in the North Carolina mountains during the round-up. The two Indians were subsequently tracked down and executed by Chief Euchella's band of Cherokees in exchange for a deal with the Army to avoid their own removal. The Cherokees were then marched overland to departure points at Ross’s Landing (Chattanooga, Tennessee

) and Gunter’s Landing (Guntersville, Alabama

) on the Tennessee River

, and forced on to flatboats and the steamers "Smelter" and "Little Rock". Unfortunately, a drought brought low water levels on the rivers, requiring frequent unloading of vessels to evade river obstacles and shoals. The Army directed Removal was characterized by many deaths and desertions, and this part of the Cherokee Removal proved to be a fiasco and Gen. Scott ordered suspension of further removal efforts. The Army-operated groups were :

Muster rolls for groups # 1 and 4 are in the records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs and # 2 in records of the Army Continental Commands (Eastern Division, Gen. Winfield Scott's papers) in the National Archives. There are daily journals of conductors for groups # 1 and 3 among Special Files of the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

The deaths and desertions in the Army's boat detachments caused Gen Scott to suspend the Army's Removal efforts, and the remaining Cherokees were put into eleven internment camps, mostly located near Ross' Landing (now Chattanooga, TN) and at Red Clay, Bedwell Springs, Chatata, Mouse Creek, Rattlesnake Springs, Chestooe, and Calhoun (site of the former Cherokee Agency) located within Bradley County, TN and one camp (Fort Payne) in Alabama.

The deaths and desertions in the Army's boat detachments caused Gen Scott to suspend the Army's Removal efforts, and the remaining Cherokees were put into eleven internment camps, mostly located near Ross' Landing (now Chattanooga, TN) and at Red Clay, Bedwell Springs, Chatata, Mouse Creek, Rattlesnake Springs, Chestooe, and Calhoun (site of the former Cherokee Agency) located within Bradley County, TN and one camp (Fort Payne) in Alabama.

Cherokees remained in the camps during the summer of 1838 and were plagued by dysentery

and other illnesses, which led to 353 deaths. A group of Cherokees petitioned General Scott for a delay until cooler weather made the journey less hazardous. This was granted; meanwhile Chief Ross, finally accepting defeat, managed to have the remainder of the removal turned over to the supervision of the Cherokee Council. Although there were some objections within the U.S. government because of the additional cost, General Scott awarded a contract for removing the remaining 11,000 Cherokees under the supervision of Principal Chief Ross, with expenses to be paid by the Army.

The "Trail of Tears."

There exist muster rolls for four (Benge, Chuwaluka, G. Hicks, and Hildebrand) of the 12 wagon trains and payrolls of officials for all 13 detachments among the personal papers of Principal Chief John Ross in the Gilcrease Institution in Tulsa, OK.

The number of people who died as a result of the Trail of Tears has been variously estimated. American doctor and missionary Elizur Butler, who made the journey with the Daniel Colston wagon train, estimated 2,000 deaths in the Army removal and internment camps and perhaps another 2,000 on the trail; his total of 4,000 deaths remains the most cited figure, although he acknowledged these were estimates without having seen government or tribal records. A scholarly demographic

The number of people who died as a result of the Trail of Tears has been variously estimated. American doctor and missionary Elizur Butler, who made the journey with the Daniel Colston wagon train, estimated 2,000 deaths in the Army removal and internment camps and perhaps another 2,000 on the trail; his total of 4,000 deaths remains the most cited figure, although he acknowledged these were estimates without having seen government or tribal records. A scholarly demographic

study in 1973 estimated 2,000 total deaths; another, in 1984, concluded that a total of 6,000 people died. The 4000 figure or one quarter of the tribe was also used by the Smithsonian anthropologist, James Mooney. Since 16,000 Cherokees were enumerated on the 1835 Census, and about 12,000 emigrated in 1838, ergo 4000 needed accounting for. Note that some 1500 Cherokees remained in North Carolina, so the higher fatality numbers are unlikely. In addition, nearly 400 Creek or Muskogee Indians who had avoided being removed earlier, fled into the Cherokee Nation and became part of the latter's Removal.

An accounting of the exact number of fatalities during the Removal is also related to discrepancies in expense accounts submitted by Chief John Ross after the Removal that the Army considered inflated and possibly fraudulent. Ross claimed rations for 1600 more Cherokees than were counted by an Army officer, Captain Page, at Ross' Landing as Cherokee groups left their homeland and another Army officer, Captain Stephenson, at Fort Gibson counted them as they arrived in Indian Territory. Ross' accounts are consistently higher numbers than that of the Army disbursing agents. The Van Buren administration refused to pay Ross, but the later Tyler administration eventually approved disbursing more than $500,000 to the Principal Chief in 1842.

In addition, some Cherokees traveled from east to west more than once. Many deserters from the Army's boat detachments in June 1838 later emigrated in the twelve Ross wagon trains. There were transfers between groups, and later join ups and desertions were not always recorded. Jesse Mayfield was a white man with a Cherokee family went twice (first voluntarily in B.B. Cannon's detachment in 1837 to Indian Territory; unhappy there, he returned to the Cherokee Nation; and in Oct. 1838 was Wagon Master for the Bushyhead Detachment. An Army disbursing agent discovered that a Cherokee named Justis Fields travelled with government funds three times under different aliases. A mixed-blood named James Bigby, Jr. travelled to Indian Territory five times (three as government interpreter for different detachments, as Commissary for the Colston detachment, and as an individual in 1840). In addition, a small but significant number of mixed-bloods and whites with Cherokee families petitioned to become citizens of Alabama, Georgia, North Carolina, or Tennessee and thus ceased to be considered Cherokees.

During the journey, it is said that the people would sing “Amazing Grace

”, using its inspiration to improve morale. The traditional Christian hymn had previously been translated into Cherokee by the missionary Samuel Worcester

with Cherokee assistance. The song has since become a sort of anthem for the Cherokee people.

s the troops fanned out across the Nation, invading every hamlet, every cabin, rooting out the inhabitants at bayonet point. The Cherokees hardly had time to realize what was happening as they were prodded like so many sheep toward the concentration camps, threatened with knives and pistols, beaten with rifle butts if they resisted."

Another Cherokee, this time a child called Samuel Cloud turned 9 years old on the Trail of Tears. Samuel's written memory is retold by his great-great grandson, Micheal Rutledge, in his paper Forgiveness in the Age of Forgetfulness. Micheal, a citizen of the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma

, is a law student at Arizona State University

:

Ethics are always a subjective thing, but the sheer cruelty exhibited toward the Indian people seems hard to deny. However, not all Americans of 1838 closed their eyes to this sort of brutality. There were those Americans who were morally distraught at what they saw. Some spoke up publicly. One was Ralph Waldo Emerson

. In his Letter To Martin Van Buren

, President of the United States, April 23, 1838, he wrote:

Another was John G Burnett, whose memories of what he had witnessed both haunted and enraged him till his last days. His own words explain best.

Burnett's story of the removal can not be validated. The documents show that he fabricated a large part of his claimed experiences. He did participate in the initial round up of the Cherokees as a Tennessee Volunteer and not as a U.S. military person. He claims to have seen the 645 wagons used by the tribe in the removal. Considering that there were ca 14 detachments, leaving from various places and at various times, never would there have been 645 wagons in one spot. Further he claims to have witnessed Mrs. Ross, on horseback, surrendering her blanket during a snow storm to protect a child, and subsequently dying as a result of her generosity. Burnett says Mrs. Ross was buried in an unmarked grave. At the time of Mrs. Ross death she was on the ship Victoria with her husband, John Ross and some 225 other people. She was not buried in an unmarked grave. Quatie Ross is buried in Little Rock in one of the town's early cemeteries. A picture of her grave marker can be seen on the web. (see 'John G. Burnett's Account' pp. 337-341 in "Cherokee Emigration: Reconstructing Reality", The Chronicles of Oklahoma, Vol. LXXX, No. 3, Fall, 2002.

Cherokees who were removed initially settled near Tahlequah, Oklahoma

Cherokees who were removed initially settled near Tahlequah, Oklahoma

. The political turmoil resulting from the Treaty of New Echota and the Trail of Tears led to the assassinations of Major Ridge, John Ridge, and Elias Boudinot; of those targeted for assassination that day, only Stand Watie escaped his assassins. The population of the Cherokee Nation eventually rebounded, and today the Cherokees are the largest American Indian group in the United States.

There were some exceptions to removal. Perhaps 1,000 Cherokees evaded the U.S. soldiers and lived off the land in Georgia and other states. Those Cherokees who lived on private, individually-owned lands (rather than communally-owned tribal land) were not subject to removal. In North Carolina, about 400 Cherokees led by Yonaguska

lived on land along the Oconaluftee River in the Great Smoky Mountains

owned by a white man named William Holland Thomas

(who had been adopted by Cherokees as a boy), and were thus not subject to removal, and these were joined by a smaller band of about 150 along the Nantahala River led by Utsala. Along with a group living in Snowbird and another along the Cheoah River

in a community called Tomotley, these North Carolina Cherokees became the Eastern Band of the Cherokee Nation

, numbering approximately 1000. According to a roll taken the year after the removal (1839), there were in addition some 400 of Georgia, Tennessee, and Alabama, and these also joined the EBCI.

The Trail of Tears is generally considered to be one of the most regrettable episodes in American history. To commemorate the event, the U.S. Congress designated the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail in 1987. It stretches across nine states for 2200 miles (3,540.5 km).

In 2004, during the 108th Congress

, Senator Sam Brownback

(Republican

of Kansas

) introduced a joint resolution (Senate Joint Resolution 37) to “offer an apology to all Native Peoples on behalf of the United States” for past “ill-conceived policies” by the United States Government regarding Indian Tribes. It passed in the U.S. Senate in February 2008

Documents:

Articles:

Audio:

Trail of Tears

The Trail of Tears is a name given to the forced relocation and movement of Native American nations from southeastern parts of the United States following the Indian Removal Act of 1830...

, refers to the forced relocation

Ethnic cleansing

Ethnic cleansing is a purposeful policy designed by one ethnic or religious group to remove by violent and terror-inspiring means the civilian population of another ethnic orreligious group from certain geographic areas....

between 1836 to 1839 of the Cherokee

Cherokee

The Cherokee are a Native American people historically settled in the Southeastern United States . Linguistically, they are part of the Iroquoian language family...

Nation from their lands in Georgia

Georgia (U.S. state)

Georgia is a state located in the southeastern United States. It was established in 1732, the last of the original Thirteen Colonies. The state is named after King George II of Great Britain. Georgia was the fourth state to ratify the United States Constitution, on January 2, 1788...

, Texas

Texas

Texas is the second largest U.S. state by both area and population, and the largest state by area in the contiguous United States.The name, based on the Caddo word "Tejas" meaning "friends" or "allies", was applied by the Spanish to the Caddo themselves and to the region of their settlement in...

, Tennessee

Tennessee

Tennessee is a U.S. state located in the Southeastern United States. It has a population of 6,346,105, making it the nation's 17th-largest state by population, and covers , making it the 36th-largest by total land area...

, Alabama

Alabama

Alabama is a state located in the southeastern region of the United States. It is bordered by Tennessee to the north, Georgia to the east, Florida and the Gulf of Mexico to the south, and Mississippi to the west. Alabama ranks 30th in total land area and ranks second in the size of its inland...

, and North Carolina

North Carolina

North Carolina is a state located in the southeastern United States. The state borders South Carolina and Georgia to the south, Tennessee to the west and Virginia to the north. North Carolina contains 100 counties. Its capital is Raleigh, and its largest city is Charlotte...

to the Indian Territory

Indian Territory

The Indian Territory, also known as the Indian Territories and the Indian Country, was land set aside within the United States for the settlement of American Indians...

(present day Oklahoma

Oklahoma

Oklahoma is a state located in the South Central region of the United States of America. With an estimated 3,751,351 residents as of the 2010 census and a land area of 68,667 square miles , Oklahoma is the 28th most populous and 20th-largest state...

) in the Western United States

Western United States

.The Western United States, commonly referred to as the American West or simply "the West," traditionally refers to the region comprising the westernmost states of the United States. Because the U.S. expanded westward after its founding, the meaning of the West has evolved over time...

, which resulted in the deaths of approximately 4,000 Cherokees.

In the Cherokee language

Cherokee language

Cherokee is an Iroquoian language spoken by the Cherokee people which uses a unique syllabary writing system. It is the only Southern Iroquoian language that remains spoken. Cherokee is a polysynthetic language.-North American etymology:...

, the event is called Nu na da ul tsun yi (the place where they cried), another term is Tlo va sa (our removal). However, this phrase was not used by Cherokees at the time, and seems to be of Choctaw

Choctaw

The Choctaw are a Native American people originally from the Southeastern United States...

origin. The Cherokees were not the only American Indian

Native Americans in the United States

Native Americans in the United States are the indigenous peoples in North America within the boundaries of the present-day continental United States, parts of Alaska, and the island state of Hawaii. They are composed of numerous, distinct tribes, states, and ethnic groups, many of which survive as...

s to emigrate as a result of the Indian Removal

Indian Removal

Indian removal was a nineteenth century policy of the government of the United States to relocate Native American tribes living east of the Mississippi River to lands west of the river...

efforts. American Indians were not only removed from the American South

Southern United States

The Southern United States—commonly referred to as the American South, Dixie, or simply the South—constitutes a large distinctive area in the southeastern and south-central United States...

but also from the North

Northern United States

Northern United States, also sometimes the North, may refer to:* A particular grouping of states or regions of the United States of America. The United States Census Bureau divides some of the northernmost United States into the Midwest Region and the Northeast Region...

, Midwest

Midwestern United States

The Midwestern United States is one of the four U.S. geographic regions defined by the United States Census Bureau, providing an official definition of the American Midwest....

, Southwest

Southwestern United States

The Southwestern United States is a region defined in different ways by different sources. Broad definitions include nearly a quarter of the United States, including Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Texas and Utah...

, and Plains

Great Plains

The Great Plains are a broad expanse of flat land, much of it covered in prairie, steppe and grassland, which lies west of the Mississippi River and east of the Rocky Mountains in the United States and Canada. This area covers parts of the U.S...

regions. The Choctaws, Chickasaw

Chickasaw

The Chickasaw are Native American people originally from the region that would become the Southeastern United States...

s, and Creek Indians (Muskogee) emigrated reluctantly. The Seminole

Seminole

The Seminole are a Native American people originally of Florida, who now reside primarily in that state and Oklahoma. The Seminole nation emerged in a process of ethnogenesis out of groups of Native Americans, most significantly Creeks from what is now Georgia and Alabama, who settled in Florida in...

s in Florida

Florida

Florida is a state in the southeastern United States, located on the nation's Atlantic and Gulf coasts. It is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the north by Alabama and Georgia and to the east by the Atlantic Ocean. With a population of 18,801,310 as measured by the 2010 census, it...

resisted removal by guerrilla warfare

Guerrilla warfare

Guerrilla warfare is a form of irregular warfare and refers to conflicts in which a small group of combatants including, but not limited to, armed civilians use military tactics, such as ambushes, sabotage, raids, the element of surprise, and extraordinary mobility to harass a larger and...

with the United States Army

United States Army

The United States Army is the main branch of the United States Armed Forces responsible for land-based military operations. It is the largest and oldest established branch of the U.S. military, and is one of seven U.S. uniformed services...

for decades (1817–1850). Ultimately, some Seminoles remained in their Florida home country, while others were transported to Indian Territory in shackles. In contrast, the Cherokees resisted removal by hiring lawyers (see Worcester v. Georgia

Worcester v. Georgia

Worcester v. Georgia, 31 U.S. 515 , was a case in which the United States Supreme Court vacated the conviction of Samuel Worcester and held that the Georgia criminal statute that prohibited non-Indians from being present on Indian lands without a license from the state was unconstitutional.The...

).

The phrase, “Trail of Tears”, is used to refer to similar events endured by other Indian people, especially among the Five Civilized Tribes

Five Civilized Tribes

The Five Civilized Tribes were the five Native American nations—the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole—that were considered civilized by Anglo-European settlers during the colonial and early federal period because they adopted many of the colonists' customs and had generally good...

. The phrase originated as a description of the voluntary removal of the Choctaw nation

Choctaw Trail of Tears

The Choctaw Trail of Tears was the relocation of the Choctaw Nation from their country referred to now as the Deep South to lands west of the Mississippi River in Indian Territory in the 1830s...

in 1831.

In the fall of 1835, a census was taken by civilian officials of the US War Department to enumerate Cherokees residing in Alabama, Georgia, North Carolina, and Tennessee, with a count of 16,542 Cherokees, 201 inter-married whites, and 1592 slaves (total: 18,335 people). In October of that year Principal Chief John Ross

John Ross (Cherokee chief)

John Ross , also known as Guwisguwi , was Principal Chief of the Cherokee Native American Nation from 1828–1866...

and an Eastern visitor, John Howard Payne

John Howard Payne

John Howard Payne was an American actor, poet, playwright, and author who had most of his theatrical career and success in London. He is today most remembered as the creator of "Home! Sweet Home!", a song he wrote in 1822 that became widely popular in the United States, Great Britain, and the...

were kidnapped from Ross' Tennessee home by a renegade group of the Georgia militia

Georgia Militia

The Georgia Militia existed from 1733 to 1879. It was originally planned by General James Oglethorpe prior to the founding of the Province of Georgia, the British colony that would become the state of Georgia. One reason for the founding of the colony was to act as a buffer between the Spanish...

. Released, Ross and a delegation of tribal leaders travelled to Washington, DC to protest this high-handed action, and to lobby against the removal policy of President Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson was the seventh President of the United States . Based in frontier Tennessee, Jackson was a politician and army general who defeated the Creek Indians at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend , and the British at the Battle of New Orleans...

. In this power vacuum, U.S. Agent John F. Schermerhorn

John F. Schermerhorn

John Freeman Schermerhorn , Indian Commissioner, was born in Schenectady, New York, the son of Barnard Freeman Schermerhorn and Ariaantje Van der Bogart. In 1809 he graduated from Union College with the degree of A.B. Immediately after graduation he was sent out by the Society for the Propagation...

gathered a group of dissident Cherokees in the home of Elias Boudinot

Elias Boudinot

Elias Boudinot was a lawyer and statesman from Elizabeth, New Jersey who was a delegate to the Continental Congress and a U.S. Congressman for New Jersey...

at the tribal capitol, New Echota

New Echota

New Echota was the capital of the Cherokee Nation prior to their forced removal in the 1830s. New Echota is 3.68 miles north of present-day Calhoun, Georgia, and south of Resaca, Georgia. The site is a state park and an historic site....

, Georgia. There on December 29, 1835, this rump group signed the unauthorized Treaty of New Echota

Treaty of New Echota

The Treaty of New Echota was a treaty signed on December 29, 1835, in New Echota, Georgia by officials of the United States government and representatives of a minority Cherokee political faction, known as the Treaty Party...

, which exchanged Cherokee land in the East for lands west of the Mississippi River

Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the largest river system in North America. Flowing entirely in the United States, this river rises in western Minnesota and meanders slowly southwards for to the Mississippi River Delta at the Gulf of Mexico. With its many tributaries, the Mississippi's watershed drains...

in Indian Territory. This agreement was never accepted by the elected tribal leadership or a majority of the Cherokee people. In February, 1836 two Councils convened at Red Clay, Tennessee and at Valley Town, North Carolina (now Murphy, NC) and produced two lists totaling some 13,000 names written in the Sequoyah

Sequoyah

Sequoyah , named in English George Gist or George Guess, was a Cherokee silversmith. In 1821 he completed his independent creation of a Cherokee syllabary, making reading and writing in Cherokee possible...

writing script of Cherokees opposed to the Treaty. The lists were dispatched to Washington, DC and presented by Chief Ross to Congress. Nevertheless, a slightly modified version of the Treaty, was ratified by the U.S. Senate by a single vote on May 23, 1836, and signed into law by President

President of the United States

The President of the United States of America is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president leads the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces....

Jackson. The Treaty provided a grace period until May 1838 for the tribe to voluntarily remove themselves to Indian Territory.

Georgia gold rush

These tensions between Georgia's and the Cherokee Nation were brought to a crisis by the discovery of gold near Dahlonega, GeorgiaDahlonega, Georgia

Dahlonega is a city in Lumpkin County, Georgia, United States, and is its county seat. As of the 2010 census, the city had a population of 5,242....

, in 1828, resulting in the Georgia Gold Rush

Georgia Gold Rush

The Georgia Gold Rush was the second significant gold rush in the United States. It started in 1828 in the present day Lumpkin County near county seat Dahlonega, and soon spread through the North Georgia mountains, following the Georgia Gold Belt. By the early 1840s, gold became harder to find...

, the first gold rush

Gold rush

A gold rush is a period of feverish migration of workers to an area that has had a dramatic discovery of gold. Major gold rushes took place in the 19th century in Australia, Brazil, Canada, South Africa, and the United States, while smaller gold rushes took place elsewhere.In the 19th and early...

in U.S. history. Hopeful gold speculators began trespassing on Cherokee lands, and pressure began to mount on the Georgia government to fulfill the promises of the Compact of 1802

Compact of 1802

The Compact of 1802 was a compact made by U.S. president Thomas Jefferson in 1802 to the state of Georgia. In it, the United States paid Georgia 1.25 million U.S. dollars for its central and western lands , and promised that the U.S...

.

When Georgia moved to extend state laws over Cherokee tribal lands in 1830, the matter went to the U.S. Supreme Court

Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States is the highest court in the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all state and federal courts, and original jurisdiction over a small range of cases...

. In Cherokee Nation v. Georgia

Cherokee Nation v. Georgia

Cherokee Nation v. Georgia, , was a United States Supreme Court case. The Cherokee Nation sought a federal injunction against laws passed by the state of Georgia depriving them of rights within its boundaries, but the Supreme Court did not hear the case on its merits...

(1831), the Marshall court

John Marshall

John Marshall was the Chief Justice of the United States whose court opinions helped lay the basis for American constitutional law and made the Supreme Court of the United States a coequal branch of government along with the legislative and executive branches...

ruled that the Cherokees were not a sovereign and independent nation, and therefore refused to hear the case. However, in Worcester v. State of Georgia (1832), the Court ruled that Georgia could not impose laws in Cherokee territory, since only the national government — not state governments — had authority in Indian affairs.

President Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson was the seventh President of the United States . Based in frontier Tennessee, Jackson was a politician and army general who defeated the Creek Indians at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend , and the British at the Battle of New Orleans...

has often been quoted as defying the Supreme Court with the words: “John Marshall has made his decision; now let him enforce it!” Jackson probably never said this, but he was fully committed to the policy. He had no desire to use the power of the national government to protect the Cherokees from Georgia, since he was already entangled with states’ rights

States' rights

States' rights in U.S. politics refers to political powers reserved for the U.S. state governments rather than the federal government. It is often considered a loaded term because of its use in opposition to federally mandated racial desegregation...

issues in what became known as the nullification crisis

Nullification Crisis

The Nullification Crisis was a sectional crisis during the presidency of Andrew Jackson created by South Carolina's 1832 Ordinance of Nullification. This ordinance declared by the power of the State that the federal Tariff of 1828 and 1832 were unconstitutional and therefore null and void within...

. With the Indian Removal Act

Indian Removal Act

The Indian Removal Act was signed into law by President Andrew Jackson on May 28, 1830.The Removal Act was strongly supported in the South, where states were eager to gain access to lands inhabited by the Five Civilized Tribes. In particular, Georgia, the largest state at that time, was involved in...

of 1830, the U.S. Congress

United States Congress

The United States Congress is the bicameral legislature of the federal government of the United States, consisting of the Senate and the House of Representatives. The Congress meets in the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C....

had given Jackson authority to negotiate removal treaties, exchanging Indian land in the East for land west of the Mississippi River. Jackson used the dispute with Georgia to put pressure on the Cherokees to sign a removal treaty.

Georgia and the Cherokee Nation

The rapidly expanding population of the United States early in the 19th century created tensions with Native American tribes located within the borders of the various states. While state governments did not want independent Indian enclaves within state boundaries, Indian tribes did not want to relocate or to give up their distinct identities.With the Compact of 1802

Compact of 1802

The Compact of 1802 was a compact made by U.S. president Thomas Jefferson in 1802 to the state of Georgia. In it, the United States paid Georgia 1.25 million U.S. dollars for its central and western lands , and promised that the U.S...

, the state of Georgia

Georgia (U.S. state)

Georgia is a state located in the southeastern United States. It was established in 1732, the last of the original Thirteen Colonies. The state is named after King George II of Great Britain. Georgia was the fourth state to ratify the United States Constitution, on January 2, 1788...

relinquished to the national government its western land claims (which became the states of Alabama

Alabama

Alabama is a state located in the southeastern region of the United States. It is bordered by Tennessee to the north, Georgia to the east, Florida and the Gulf of Mexico to the south, and Mississippi to the west. Alabama ranks 30th in total land area and ranks second in the size of its inland...

and Mississippi

Mississippi

Mississippi is a U.S. state located in the Southern United States. Jackson is the state capital and largest city. The name of the state derives from the Mississippi River, which flows along its western boundary, whose name comes from the Ojibwe word misi-ziibi...

). In exchange, the national government promised to eventually conduct treaties to relocate those Indian tribes living within Georgia, thus giving Georgia control of all land within its borders.

However, the Cherokees, whose ancestral tribal lands overlapped the boundaries of Georgia, Tennessee

Tennessee

Tennessee is a U.S. state located in the Southeastern United States. It has a population of 6,346,105, making it the nation's 17th-largest state by population, and covers , making it the 36th-largest by total land area...

, North Carolina

North Carolina

North Carolina is a state located in the southeastern United States. The state borders South Carolina and Georgia to the south, Tennessee to the west and Virginia to the north. North Carolina contains 100 counties. Its capital is Raleigh, and its largest city is Charlotte...

, and Alabama, declined to move. They established a capital in 1825 at New Echota

New Echota

New Echota was the capital of the Cherokee Nation prior to their forced removal in the 1830s. New Echota is 3.68 miles north of present-day Calhoun, Georgia, and south of Resaca, Georgia. The site is a state park and an historic site....

(near present-day Calhoun, Georgia

Calhoun, Georgia

Calhoun is a city in Gordon County, Georgia, United States. As of the 2010 census, the city had a population of 15,650. The city is the county seat of Gordon County.-Geography:Calhoun is located at , along the Oostanaula River....

). Furthermore, led by principal Chief John Ross

John Ross (Cherokee chief)

John Ross , also known as Guwisguwi , was Principal Chief of the Cherokee Native American Nation from 1828–1866...

and Major Ridge

Major Ridge

Major Ridge, The Ridge was a Cherokee Indian member of the tribal council, a lawmaker, and a leader. He was a veteran of the Chickamauga Wars, the Creek War, and the First Seminole War.Along with Charles R...

, the speaker of the Cherokee National Council, the Cherokees adopted a written constitution on 26 July 1827, declaring the Cherokee Nation to be a sovereign and independent nation.

The Cherokee land that was lost proved to be extremely valuable. Upon these lands were the alignments for the future rights-of-way for rail and road communications between the eastern Piedmont slopes of the Appalachian Mountains, the Ohio river in Kentucky and the Tennessee river valley at Chattanooga

Chattanooga, Tennessee

Chattanooga is the fourth-largest city in the US state of Tennessee , with a population of 169,887. It is the seat of Hamilton County...

. This location is still a strategic economic asset and is the basis for the tremendous success of Atlanta, Georgia

Georgia (U.S. state)

Georgia is a state located in the southeastern United States. It was established in 1732, the last of the original Thirteen Colonies. The state is named after King George II of Great Britain. Georgia was the fourth state to ratify the United States Constitution, on January 2, 1788...

, as a regional transportation and logistics center. Georgia’s appropriation of these lands from the Cherokee kept the wealth out of the hands of the Cherokee Nation.

The Cherokee lands in Georgia were settled upon by the Cherokee for the simple reason that they were and still are the shortest and most easily traversed route between the only fresh water sourced settlement location at the southeastern tip of the Appalachian range (the Chattahoochee River), and the natural passes, ridges, and valleys which lead to the Tennessee river at what is today, Chattanooga. From Chattanooga there was and is the potential for a year-round water transport to St. Louis and the west (via the Ohio and Mississippi rivers), or to as far east as Pittsburgh, PA.

Treaty of New Echota

Major Ridge

Major Ridge, The Ridge was a Cherokee Indian member of the tribal council, a lawmaker, and a leader. He was a veteran of the Chickamauga Wars, the Creek War, and the First Seminole War.Along with Charles R...

, his son John Ridge

John Ridge

John Ridge, born Skah-tle-loh-skee , was from a prominent family of the Cherokee Nation, then located in present-day Georgia. He married Sarah Bird Northup, of a New England family, whom he had met while studying at the Foreign Mission School in Cornwall, Connecticut...

, and nephews Elias Boudinot

Elias Boudinot (Cherokee)

Elias Boudinot , was a member of an important Cherokee family in present-day Georgia. They believed that rapid acculturation was critical to Cherokee survival. In 1828 Boudinot became the editor of the Cherokee Phoenix, which was published in Cherokee and English...

and Stand Watie

Stand Watie

Stand Watie , also known as Standhope Uwatie, Degataga , meaning “stand firm”), and Isaac S. Watie, was a leader of the Cherokee Nation and a brigadier general of the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War...

, they became known as the “Ridge Party”, or the “Treaty Party”. The Ridge Party believed that it was in the best interest of the Cherokees to get favorable terms from the U.S. government, before white squatters, state governments, and violence made matters worse. John Ridge began unauthorized talks with the Jackson administration in the late 1820s. Meanwhile, in anticipation of the Cherokee removal, the state of Georgia began holding lotteries

Georgia Land Lottery

The Georgia land lotteries were an early nineteenth century system of land distribution in Georgia. Under this system, qualifying citizens could register for a chance to win lots of land that had formerly belonged to the Creek Indians and the Cherokee Nation. The lottery system was utilized by the...

in order to divide up the Cherokee tribal lands among white Georgians.

However, Principal Chief John Ross

John Ross (Cherokee chief)

John Ross , also known as Guwisguwi , was Principal Chief of the Cherokee Native American Nation from 1828–1866...

and the majority of the Cherokee people remained adamantly opposed to removal. Political maneuvering began: Chief Ross canceled the tribal elections in 1832, the Council threatened to impeach the Ridges, and a prominent member of the Treaty Party (John Walker, Jr.) was murdered. The Ridges responded by eventually forming their own council, representing only a fraction of the Cherokee people. This split the Cherokee Nation into two factions: those following Ross, known as the National Party, and those of the Treaty Party, who elected

William A. Hicks

William Hicks (Cherokee chief)

William Abraham Hicks became Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation in 1827 after being elected to succeed his older brother, Charles R. Hicks, the longtime Second Principal Chief who died on 20 January 1827, just two weeks after assuming office as Principal Chief...

, who had briefly succeeded his brother Charles R. Hicks

Charles R. Hicks

Charles Renatus Hicks was one of the most important Cherokee leaders in the early 19th century; together with James Vann and Major Ridge, he was one of a triumvirate of younger chiefs urging the tribe to acculturate to European-American ways and supported a Moravian mission school to educate the...

as Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation to act as titular leader of the pro-Treaty faction, with former National Council clerk Alexander McCoy as his assistant.

In 1835, Jackson appointed Reverend John F. Schermerhorn

John F. Schermerhorn

John Freeman Schermerhorn , Indian Commissioner, was born in Schenectady, New York, the son of Barnard Freeman Schermerhorn and Ariaantje Van der Bogart. In 1809 he graduated from Union College with the degree of A.B. Immediately after graduation he was sent out by the Society for the Propagation...

as a treaty commissioner. The U.S. government proposed to pay the Cherokee Nation US$4.5 million (among other considerations) to remove themselves. These terms were rejected in October 1835 by the Cherokee Nation Council meeting at Red Clay

Red Clay State Park

Red Clay State Historic Park is located in southern Bradley County in Cleveland, Tennessee. The park is also listed as an interpretive center along the Cherokee Trail of Tears...

. Chief Ross, attempting to bridge the gap between his administration and the Ridge Party, traveled to Washington with a party that included John Ridge and Stand Watie to open new negotiations, but they were turned away and told to deal with Schermerhoerne.

Meanwhile, Schermerhorn organized a meeting with the pro-removal council members at New Echota

New Echota

New Echota was the capital of the Cherokee Nation prior to their forced removal in the 1830s. New Echota is 3.68 miles north of present-day Calhoun, Georgia, and south of Resaca, Georgia. The site is a state park and an historic site....

, Georgia

Georgia (U.S. state)

Georgia is a state located in the southeastern United States. It was established in 1732, the last of the original Thirteen Colonies. The state is named after King George II of Great Britain. Georgia was the fourth state to ratify the United States Constitution, on January 2, 1788...

. Only five hundred Cherokees (out of thousands) responded to the summons, and, on December 30, 1835, twenty-one proponents of Cherokee removal (Major Ridge, Elias Boudinot, James Foster, Testaesky, Charles Moore, George Chambers, Tahyeske, Archilla Smith, Andrew Ross (younger brother of Chief John Ross), William Lassley, Caetehee, Tegaheske, Robert Rogers, John Gunter, John A. Bell, Charles Foreman, William Rogers, George W. Adair, James Starr, and Jesse Halfbreed), signed or left “X” marks on the Treaty of New Echota

Treaty of New Echota

The Treaty of New Echota was a treaty signed on December 29, 1835, in New Echota, Georgia by officials of the United States government and representatives of a minority Cherokee political faction, known as the Treaty Party...

after those present voted unanimously for its approval. John Ridge and Stand Watie signed the treaty when it was brought to Washington. Chief Ross, as expected, refused.

This treaty gave up all the Cherokee land east of the Mississippi

Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the largest river system in North America. Flowing entirely in the United States, this river rises in western Minnesota and meanders slowly southwards for to the Mississippi River Delta at the Gulf of Mexico. With its many tributaries, the Mississippi's watershed drains...

in return for five million dollars to be disbursed on a per capita

Per capita

Per capita is a Latin prepositional phrase: per and capita . The phrase thus means "by heads" or "for each head", i.e. per individual or per person...

basis, an additional half-million dollars for educational funds, title in perpetuity to an amount of land in Indian Territory equal to that given up, and full compensation for all property left in the East. There was also a clause in the treaty as signed allowing Cherokee who so desired to remain and become citizens of the states in which they resided on 160 acre (0.6474976 km²) of land, but that was later stricken out by President Jackson.

Despite the protests by the Cherokee National Council and principal Chief Ross that the document was a fraud, Congress ratified the treaty on May 23, 1836, by just one vote.

Voluntary removal

The Treaty provided a two year grace period for Cherokees to willingly emigrate to Indian Territory. A number of Cherokees (mostly members of the Ridge faction) accepted government funds for subsistence and transportation. Many travelled as individuals or families, but there were several organized groups:- John S. Young, Conductor; via river boats; 466 Cherokees and 6 Creeks, left March 1, 1837; arrived March 28, 1837; included Major RidgeMajor RidgeMajor Ridge, The Ridge was a Cherokee Indian member of the tribal council, a lawmaker, and a leader. He was a veteran of the Chickamauga Wars, the Creek War, and the First Seminole War.Along with Charles R...

and Stand WatieStand WatieStand Watie , also known as Standhope Uwatie, Degataga , meaning “stand firm”), and Isaac S. Watie, was a leader of the Cherokee Nation and a brigadier general of the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War...

. - B.B. Cannon, Conductor; overland; 355 persons (15 deaths); left Oct.15, 1837; arrived Dec.29, 1837; included James Starr.

- Rev. John Huss, Conductor, overland; 74 persons; left Nov.11, 1837; arrival unknown.

- Robert B. Vann, leader; 133 persons; left Dec.1, 1837; arrived March 17, 1838.

- Lt. Edward Deas, Conductor; by boat; 252 persons (2 deaths); left April 6, 1838; arrived May 1, 1838.

- 162 persons; left May 25, 1838; arrived Oct. 21, 1838.

- 96 persons; date left unknown; arrived June 1, 1838.

- Lt. Edward Deas and John Adair Bell, Co-Conductors, overland, 660 persons left Oct. 11, 1838; 650 arrived Jan. 7, 1839.

There are muster rolls for groups # 1, 3 – 6 and daily journals of conductors for groups # 2 and 5 among records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs in the National Archives. Despite the government blandishments, only a few hundred volunteered to accept the Treaty terms for Removal.

Forced removal

Ralph Waldo Emerson

Ralph Waldo Emerson was an American essayist, lecturer, and poet, who led the Transcendentalist movement of the mid-19th century...

wrote a letter to Jackson’s successor, President Martin Van Buren

Martin Van Buren

Martin Van Buren was the eighth President of the United States . Before his presidency, he was the eighth Vice President and the tenth Secretary of State, under Andrew Jackson ....

, urging him not to inflict “so vast an outrage upon the Cherokee Nation.”

Nevertheless, as the May 23, 1838, deadline for voluntary removal approached, President Van Buren assigned General Winfield Scott

Winfield Scott

Winfield Scott was a United States Army general, and unsuccessful presidential candidate of the Whig Party in 1852....

to head the forcible removal operation. He arrived at New Echota on May 17, 1838, in command of U.S. Army and state militia totalling about 7,000 soldiers. They began rounding up Cherokees in Georgia on May 26, 1838; ten days later, operations began in Tennessee, North Carolina, and Alabama. Men, women, and children were removed at gunpoint from their homes over three weeks and gathered together in camps, often with very few of their possessions. Another soldier, Private John G. Burnett later wrote "Future generations will read and condemn the act and I do hope posterity will remember that private soldiers like myself, and like the four Cherokees who were forced by General Scott to shoot an Indian Chief and his children, had to execute the orders of our superiors. We had no choice in the matter."

This story is perhaps a garbled version of the episode when a Cherokee named Tsali

Tsali

Tsali, originally of Coosawattee Town , was a noted figure at two different periods of Cherokee history, both of them vital.From which of the main divisions of the Cherokee prior to the American Revolution he came is not known, but records do indicate that as a young man he followed Dragging Canoe...

or Charley and three others killed two soldiers in the North Carolina mountains during the round-up. The two Indians were subsequently tracked down and executed by Chief Euchella's band of Cherokees in exchange for a deal with the Army to avoid their own removal. The Cherokees were then marched overland to departure points at Ross’s Landing (Chattanooga, Tennessee

Chattanooga, Tennessee

Chattanooga is the fourth-largest city in the US state of Tennessee , with a population of 169,887. It is the seat of Hamilton County...

) and Gunter’s Landing (Guntersville, Alabama

Guntersville, Alabama

Guntersville is a city in Marshall County, Alabama, United States and is included in the Huntsville-Decatur Combined Statistical Area. At the 2010 census, the population of the city was 8,197. The city is the county seat of Marshall County. Guntersville is located in a HUBZone as identified by the...

) on the Tennessee River

Tennessee River

The Tennessee River is the largest tributary of the Ohio River. It is approximately 652 miles long and is located in the southeastern United States in the Tennessee Valley. The river was once popularly known as the Cherokee River, among other names...

, and forced on to flatboats and the steamers "Smelter" and "Little Rock". Unfortunately, a drought brought low water levels on the rivers, requiring frequent unloading of vessels to evade river obstacles and shoals. The Army directed Removal was characterized by many deaths and desertions, and this part of the Cherokee Removal proved to be a fiasco and Gen. Scott ordered suspension of further removal efforts. The Army-operated groups were :

- Lt. Edward Deas, Conductor; 800 left June 6, 1838 by boat; 489 arrived June 19, 1838.

- Lt. Monroe, Conductor, 164 persons left June 12, 1838; arrival unknown.

- Lt. R.H.K. Whiteley, ca. 800 persons left June 13, 1838 by boat, arrived Aug. 5, 1838 (70 deaths).

- Captain Gustavus S. Drane, Conductor, 1072 left June 17, 1838 by boat, 635 arrived Sept. 7, 1838 (146 deaths, 2 births).

Muster rolls for groups # 1 and 4 are in the records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs and # 2 in records of the Army Continental Commands (Eastern Division, Gen. Winfield Scott's papers) in the National Archives. There are daily journals of conductors for groups # 1 and 3 among Special Files of the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

Internment camps

Cherokees remained in the camps during the summer of 1838 and were plagued by dysentery

Dysentery

Dysentery is an inflammatory disorder of the intestine, especially of the colon, that results in severe diarrhea containing mucus and/or blood in the faeces with fever and abdominal pain. If left untreated, dysentery can be fatal.There are differences between dysentery and normal bloody diarrhoea...

and other illnesses, which led to 353 deaths. A group of Cherokees petitioned General Scott for a delay until cooler weather made the journey less hazardous. This was granted; meanwhile Chief Ross, finally accepting defeat, managed to have the remainder of the removal turned over to the supervision of the Cherokee Council. Although there were some objections within the U.S. government because of the additional cost, General Scott awarded a contract for removing the remaining 11,000 Cherokees under the supervision of Principal Chief Ross, with expenses to be paid by the Army.

Reluctant removal

Chief John Ross organized 12 wagon trains, each with about 1000 persons and conducted by veteran full-blood tribal leaders or educated mixed bloods. Each wagon train was assigned physicians, interpreters (to help the physicians), commissaries, managers, wagon masters, teamsters, and even grave diggers. Chief Ross also purchased the steamboat "Victoria" in which his own and tribal leaders' families could travel in some comfort. Lewis Ross, the Chief's brother, was the main contractor and furnished forage, rations, and clothing for the wagon trains. Although this arrangement was an improvement for all concerned, disease and exposure still took many lives. This is the part of the Removal usually identified asThe "Trail of Tears."

- Daniel Colston, Conductor (first choice Hair Conrad became ill); Asst. Conductor Jefferson Nevins; 710 persons left Oct.5, 1838 from Agency camp and 654 people arrived at Woodall's place in Indian Territory on Jan. 4, 1839 (57 deaths, 9 births, 24 deserters).

- Elijah Hicks, Conductor; White Path (died near Hopkinsville, KentuckyHopkinsville, KentuckyHopkinsville is a city in Christian County, Kentucky, United States. The population was 31,577 at the 2010 census. It is the county seat of Christian County.- History :...

) and William Arnold, Asst. Conductors; 809 persons left Oct.4, 1838 from Camp Ross on Gunstocker Creek and 744 people arrived Jan.4, 1839 at Mrs. Webber's place in Indian Territory. - Rev. Jesse Bushyhead, Conductor; Roman Nose, Asst. Conductor; 864 left Oct. 16, 1838 from Chatata Creek camp and 898 arrived Feb. 27, 1839 at Fort Wayne, Ind. Ty. (38 deaths, 6 births, 151 deserters, 171 additions).

- Capt. John Benge, Conductor; George C. Lowrey, Jr. Asst. Conductor; 1079 persons left Fort Payne camp, Alabama Oct. 1, 1838 and 1132 arrived Jan.11, 1839 at Mrs. Webber's place, Ind. Ty. (33 deaths, 3 births).

- Situake, Conductor; Rev. Evan Jones, Asst. Conductor; 1205 persons left Oct. 19, 1838 from Savannah Creek camp and 1033 arrived Feb. 2, 1839 (at Beatties' Prairie, Ind.Ty. (71 deaths, 5 births).

- Capt. Old Fields, Conductor; Rev. Stephen Foreman, Asst. Conductor; 864 persons left Oct. 10, 1838 from Candy's Creek camp and 898 arrived Feb. 2, 1839 at Beatties' Prairie (57 deaths, 19 births, 10 deserters, 6 additions).

- Moses Daniel, Conductor; George Still, Sr. Asst. Conductor; 1031 persons left from Agency camp on Oct.23, 1838 and 924 arrived March 2, 1839 at Mrs. Webber's (48 deaths, 6 births).

- Chuwaluka (a.k.a. Bark), Conductor; James D. Wofford (fired for drunkenness) and Thomas N. Clark, Jr. Asst. Conductors; 1120 left Oct.27, 1838 from Mouse Creek camp and 970 arrived March 1, 1839 at Fort Wayne.

- Judge James Brown, Conductor; Lewis Hildebrand, Asst. Conductor; 745 left Oct. 31, 1838 from Ootewah Creek camp and 717 arrived March 3, 1839 at Park Hill.

- George Hicks, Conductor; Collins McDonald, Asst. Conductor; 1031 left Nov. 4, 1838 from Mouse Creek camp and 1039 arrived March 14, 1839 near Fort Wayne.

- Richard Taylor, Conductor; Walter Scott Adair, Asst. Conductor; 897 left Nov. 6, 1838 from Ooltewah Creek camp and 942 arrived March 24, 1839 at Woodall's place(55 deaths, 15 births). Missionary Rev. Daniel Butrick accompanied this detachment, and his daily journal has been published.

- Peter Hildebrand, Conductor; James Vann Hildebrand, Asst. Conductor; 1449 left Nov. 8, 1838 Ocoe camp and 1311 arrived March 25, 1839 near Woodall's place.

- "Victoria" Detachment – John Drew Conductor; John Golden Ross, Asst. Conductor; 219 left Nov. 5, 1838 Agency camp and 231 arrived March 18, 1839 Tahlequah.

There exist muster rolls for four (Benge, Chuwaluka, G. Hicks, and Hildebrand) of the 12 wagon trains and payrolls of officials for all 13 detachments among the personal papers of Principal Chief John Ross in the Gilcrease Institution in Tulsa, OK.

Deaths and numbers

Demography

Demography is the statistical study of human population. It can be a very general science that can be applied to any kind of dynamic human population, that is, one that changes over time or space...

study in 1973 estimated 2,000 total deaths; another, in 1984, concluded that a total of 6,000 people died. The 4000 figure or one quarter of the tribe was also used by the Smithsonian anthropologist, James Mooney. Since 16,000 Cherokees were enumerated on the 1835 Census, and about 12,000 emigrated in 1838, ergo 4000 needed accounting for. Note that some 1500 Cherokees remained in North Carolina, so the higher fatality numbers are unlikely. In addition, nearly 400 Creek or Muskogee Indians who had avoided being removed earlier, fled into the Cherokee Nation and became part of the latter's Removal.

An accounting of the exact number of fatalities during the Removal is also related to discrepancies in expense accounts submitted by Chief John Ross after the Removal that the Army considered inflated and possibly fraudulent. Ross claimed rations for 1600 more Cherokees than were counted by an Army officer, Captain Page, at Ross' Landing as Cherokee groups left their homeland and another Army officer, Captain Stephenson, at Fort Gibson counted them as they arrived in Indian Territory. Ross' accounts are consistently higher numbers than that of the Army disbursing agents. The Van Buren administration refused to pay Ross, but the later Tyler administration eventually approved disbursing more than $500,000 to the Principal Chief in 1842.

In addition, some Cherokees traveled from east to west more than once. Many deserters from the Army's boat detachments in June 1838 later emigrated in the twelve Ross wagon trains. There were transfers between groups, and later join ups and desertions were not always recorded. Jesse Mayfield was a white man with a Cherokee family went twice (first voluntarily in B.B. Cannon's detachment in 1837 to Indian Territory; unhappy there, he returned to the Cherokee Nation; and in Oct. 1838 was Wagon Master for the Bushyhead Detachment. An Army disbursing agent discovered that a Cherokee named Justis Fields travelled with government funds three times under different aliases. A mixed-blood named James Bigby, Jr. travelled to Indian Territory five times (three as government interpreter for different detachments, as Commissary for the Colston detachment, and as an individual in 1840). In addition, a small but significant number of mixed-bloods and whites with Cherokee families petitioned to become citizens of Alabama, Georgia, North Carolina, or Tennessee and thus ceased to be considered Cherokees.

During the journey, it is said that the people would sing “Amazing Grace

Amazing Grace

"Amazing Grace" is a Christian hymn with words written by the English poet and clergyman John Newton , published in 1779. With a message that forgiveness and redemption are possible regardless of the sins people commit and that the soul can be delivered from despair through the mercy of God,...

”, using its inspiration to improve morale. The traditional Christian hymn had previously been translated into Cherokee by the missionary Samuel Worcester

Samuel Worcester

Samuel Austin Worcester , was a missionary to the Cherokee, translator of the Bible, printer and defender of the Cherokee's sovereignty. He was a party in Worcester v...

with Cherokee assistance. The song has since become a sort of anthem for the Cherokee people.

Personal narratives

Samuel Carter, author of Cherokee Sunset, writes: "Then… there came the reign of terror. From the jagged-walled stockadeStockade

A stockade is an enclosure of palisades and tall walls made of logs placed side by side vertically with the tops sharpened to provide security.-Stockade as a security fence:...

s the troops fanned out across the Nation, invading every hamlet, every cabin, rooting out the inhabitants at bayonet point. The Cherokees hardly had time to realize what was happening as they were prodded like so many sheep toward the concentration camps, threatened with knives and pistols, beaten with rifle butts if they resisted."

Another Cherokee, this time a child called Samuel Cloud turned 9 years old on the Trail of Tears. Samuel's written memory is retold by his great-great grandson, Micheal Rutledge, in his paper Forgiveness in the Age of Forgetfulness. Micheal, a citizen of the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma

Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma

The Cherokee Nation is the largest of three Cherokee federally recognized tribes in the United States. It was established in the 20th century, and includes people descended from members of the old Cherokee Nation who relocated voluntarily from the Southeast to Indian Territory and Cherokees who...

, is a law student at Arizona State University

Arizona State University

Arizona State University is a public research university located in the Phoenix Metropolitan Area of the State of Arizona...

:

I know what it is to hate. I hate those white soldiers who took us from our home. I hate the soldiers who make us keep walking through the snow and ice toward this new home that none of us ever wanted. I hate the people who killed my father and mother. I hate the white people who lined the roads in their woollen clothes that kept them warm, watching us pass. None of those white people are here to say they are sorry that I am alone. None of them care about me or my people. All they ever saw was the colour of our skin. All I see is the colour of theirs and I hate them.

Ethics are always a subjective thing, but the sheer cruelty exhibited toward the Indian people seems hard to deny. However, not all Americans of 1838 closed their eyes to this sort of brutality. There were those Americans who were morally distraught at what they saw. Some spoke up publicly. One was Ralph Waldo Emerson

Ralph Waldo Emerson

Ralph Waldo Emerson was an American essayist, lecturer, and poet, who led the Transcendentalist movement of the mid-19th century...

. In his Letter To Martin Van Buren

Martin Van Buren

Martin Van Buren was the eighth President of the United States . Before his presidency, he was the eighth Vice President and the tenth Secretary of State, under Andrew Jackson ....

, President of the United States, April 23, 1838, he wrote:

In the name of God, sir, we ask you if this be so. Do the newspapers rightly inform us?...

The piety, the principle that is left in the United States, if only in its coarsest form, a regard to the speech of men, – forbid us to entertain it as a fact. Such a dereliction of all faith and virtue, such a denial of justice, and such deafness to screams for mercy were never heard of in times of peace and in the dealing of a nation with its own allies and wards, since the earth was made. Sir, does this government think that the people of the United States are become savage and mad? From their mind are the sentiments of love and a good nature wiped clean out? The soul of man, the justice, the mercy that is the heart's heart in all men, from Maine to Georgia, does abhor this business.

In speaking thus the sentiments of my neighbors and my own, perhaps I overstep the bounds of decorum. But would it not be a higher indecorum coldly to argue a matter like this? We only state the fact that a crime is projected that confounds our understandings by its magnitude, -a crime that really deprives us as well as the Cherokees of a country, for how could we call the conspiracy that should crush these poor Indians our government, or the land that was cursed by their parting and dying imprecations our country, any more? You, sir, will bring down that renowned chair in which you sit into infamy if your seal is set to this instrument of perfidy ; and the name of this nation, hitherto the sweet omen of religion and liberty, will stink to the world.

You will not do us the injustice of connecting this remonstrance with any sectional and party feeling. It is in our hearts the simplest commandment of brotherly love. We will not have this great and solemn claim upon national and human justice huddled aside under the flimsy plea of its being a party act. Sir, to us the questions upon which the government and the people have been agitated during the past year*, touching the prostration of the currency and of trade, seem but motes in comparison. These hard times, it is true, have brought the discussion home to every farmhouse and poor man's house in this town; but it is the chirping of grasshoppers beside the immortal question whether justice shall be done by the race of civilized to the race of savage man, – whether all the attributes of reason, of civility, of justice, and even of mercy, shall be put off by the American people, and so vast an outrage upon the Cherokee Nation and upon human nature shall be consummated.

- The "questions...agitated during the past year" refers to the Panic of 1837

Panic of 1837The Panic of 1837 was a financial crisis or market correction in the United States built on a speculative fever. The end of the Second Bank of the United States had produced a period of runaway inflation, but on May 10, 1837 in New York City, every bank began to accept payment only in specie ,...

.

Another was John G Burnett, whose memories of what he had witnessed both haunted and enraged him till his last days. His own words explain best.