Capital punishment in Canada

Encyclopedia

Capital punishment in Canada dates back to 1749. Before Canada eliminated the death penalty for murder on July 14, 1976, 1,481 people were sentenced to death, with 710 executed. Of those executed, 697 were men and 13 were women. The only method used in Canada

for capital punishment

in nonmilitary contexts was hanging

. The last execution in Canada was on December 11, 1962, at Toronto's Don Jail

.

. He can be shown to have hanged at least 69 people in Canada, although his life total was probably much higher. At his death, the Toronto Telegram said he had 150 executions. He died of alcohol-related illness in Toronto on February 26, 1911, at the age of 55.

of Arthur B. English

, a British

man who became Canada's official hangman

in 1913, after Radclive's death. Ellis worked as a hangman in Canada until the botched execution of Thomasina Sarao in Montreal in 1935, in which she was decapitated.

He died in poverty in Montreal in July, 1938; and lies buried in the Mount Royal Cemetery

.

The Crime Writers of Canada

present annual literary awards – the Arthur Ellis Awards

– named after this pseudonym. Ellis is prominently featured in the 2009 documentary Hangman's Graveyard

.

Blanchard carried out many executions (for which he was not paid) in the postwar period in Canada, such as the double hanging of Leonard Jackson and Steven Suchan of the Boyd Gang

at the Don Jail in 1952, and Robert Raymond Cook's execution in Fort Saskatchewan, Alberta, in 1960.

In 1749, Peter Cartcel, a sailor aboard a ship in the Halifax harbour, stabbed Abraham Goodsides to death and wounded two other men. He was brought before a Captain’s Court where they found him to be guilty and sentenced him to death. Two days later, he swung from the yardarm of the vessel as a deterrent warning to others against following in his violent footsteps. This is one of the earliest records of capital punishment in Canada. However, it is difficult to accurately state numbers of capital punishment since there were no systematic efforts to accurately record names, dates, and locations of executions until after 1867 and many records have been forever lost owing to fires, floods, or decay.

In 1749, Peter Cartcel, a sailor aboard a ship in the Halifax harbour, stabbed Abraham Goodsides to death and wounded two other men. He was brought before a Captain’s Court where they found him to be guilty and sentenced him to death. Two days later, he swung from the yardarm of the vessel as a deterrent warning to others against following in his violent footsteps. This is one of the earliest records of capital punishment in Canada. However, it is difficult to accurately state numbers of capital punishment since there were no systematic efforts to accurately record names, dates, and locations of executions until after 1867 and many records have been forever lost owing to fires, floods, or decay.

In early years, offences such as treason

, theft, burglary, rape, pedophilia, homosexuality, and unusual sexual practices like bestiality were considered punishable by death. Authority steadily increased the number of offences that were punishable by death in order to deter the number of crimes committed. After being hanged, authority often left the body in public, usually covered with tar so that they could preserve them from weather.

After Confederation, a revision of the statutes reduced the number of offences to only three general offences that were punishable by death: murder, rape, and treason. The only case since Confederation in which the offender received the death penalty for an offence other than murder was the Métis

leader, Louis Riel

. He was convicted of high treason for his participation in the North-West Rebellion

. In 1868, Parliament also stated that the location of the execution was to be within the confines of the prison, as opposed to the public hangings in the past. As a result, by the 1870’s, the jails had begun to build the gallows five feet from the ground with a pit underneath instead of the previous high scaffold, built level with the prison wall.

In 1950, an attempt was made to abolish capital punishment. Mr. W. Ross Thatcher moved Bill No. 2 in order to amend the Criminal Code to abolish the death penalty. However, Thatcher later withdrew it for fear of Bill No. 2 not generating positive discussion and further harming the chances of abolishment. In 1956, the Joint Committee of the House and Senate recommended the retention of capital punishment as the mandatory punishment for murder, which opened the door to the possibility of abolishment

In 1961, legislation was introduced to reclassify murder into capital or non-capital offences. A capital murder involved a planned or deliberate murder, murder during violent crimes, or the murder of a police officer

or prison guard. Only capital murder carried the death sentence.

Following the success of Lester Pearson and the Liberal

party in the 1963 federal election

, and through the successive governments of Pierre Trudeau

, the federal cabinet

commuted all death sentences as a matter of policy. Hence, the de facto abolition of the death penalty in Canada occurred in 1963, with legal abolition a formality. On November 30, 1967, Bill C-168 was passed creating a five-year moratorium

on the use of the death penalty, except for murder

s of police and corrections officers. On January 26, 1973, after the expiration of the five-year experiment, the Solicitor General of Canada continued the partial ban on capital punishment, which would eventually lead to the abolition of capital punishment. On July 14, 1976, Bill C-84 was passed by a narrow margin of 130:124 in a free vote, resulting in the de jure

abolition of the death penalty, except for certain offences under the National Defence Act

. These were removed in 1998.

First-degree murder, which before abolition was the offence of capital murder, now carries a mandatory life sentence without eligibility

for parole

until the person has served 25 years of the sentence.

, 25 Canadian soldiers were executed. Most were shot for service offences such as desertion

and cowardice

, but two executions were for murder

. For details of these see List of Canadian soldiers executed during World War I.

One Canadian soldier, Pte. Harold Pringle

, was executed during the Second World War for murder.

, 29, and Arthur Lucas

, 54, convicted for separate murders, at 12:02 am on December 11, 1962 at the Don Jail

in Toronto

.

The last woman to be hanged in Canada was Marguerite Pitre on January 9, 1953, for her part in the Albert Guay affair.

and France

had experimented with a wide range of different methods of punishment such as burning at the stake, boiling in oil, beheading, pressing to death, and the guillotine, for decades. Using the philosophy that the death penalty must inflict pain upon the offender, the methods of capital punishment tended to be gruesome and violent. Thus, onlookers took it upon themselves not to commit the crimes that caused the offender so much agony.

The most common method of execution eventually became hanging

. The first method was “hoisting” in which a rope would be thrown over a beam and the convicted person would then be hoisted into the air by others pulling on the rope. The slip knot would then tightly close around the neck until strangulation. A variation of this included the person with a rope around their neck to stand on a cart and then it would be pushed from under them. This led to the development of suspension in which “the drop” caused by jerking something from underneath the offender became the main component of the execution. Executioners experimented with the length of the rope for the drop. They specifically began to discover new ways of causing instant death upon hanging. In 1872, the length of a drop extended to nearly five-feet which dislocated the neck perfectly. Almost one year later, the length of the drop was extended to seven feet.

The majority of offenders put to death by Canadian civilian authorities were executed by the "long drop" technique of hanging

developed in the United Kingdom

by William Marwood

. This method ensured that the prisoner's neck was broken instantly at the end of the drop, resulting in the prisoner dying of asphyxia

while unconscious, which was considered more humane than the slow death by strangulation which often resulted from the previous "short drop" method. The short drop sometimes gave a period of torture before death finally took place.

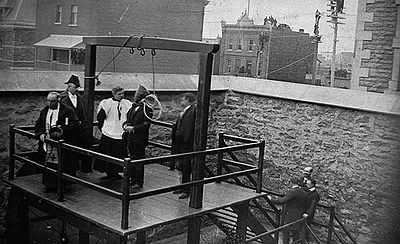

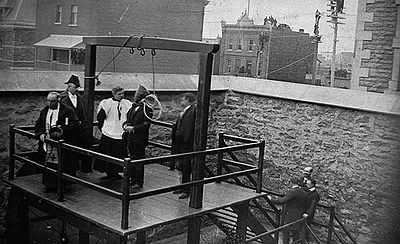

Early in his career, John Radclive persuaded several sheriffs in Ontario and Quebec to let him use an alternative method in which the condemned person was jerked into the air. A gallows of this type was used for the execution of Robert Neil at Toronto’s Don Jail

on February 29, 1888:

The hanging of Reginald Birchall in Woodstock, Ont. in November 1890 seems to be the last time a device of this kind was used. Radclive had first been exposed to executions as a Royal Navy

seaman helping with shipboard hangings of pirates in the South China Sea, and it is possible he was trying to approximate something similar to hanging a man on a ship's yardarm. After Birchall's hanging, Radclive used the traditional long drop method, as did his successors.

While hanging was a relatively humane method of execution under ideal conditions with an expert executioner, mistakes could happen. Condemned prisoners were decapitated by accident at Headingley Jail in Manitoba and Bordeaux Jail in Montreal, and a prisoner at the Don Jail in Toronto hit the floor of the room below and was strangled by the hangman.

Some Canadian jails - such as those in Toronto, Ontario, Headingley, Manitoba, and Fort Saskatchewan, Alberta - had permanent indoor execution facilities, but more typically offenders were hanged on a scaffold built for the occasion in the jail yard.

Military prisoners sentenced to death in Canada were shot by firing squad

.

described as the "morbid public" came to see something of the spectacle.

At the hanging of Stanislaus Lacroix in Hull, Quebec in 1902, for example, onlookers climbed buildings and telephone poles to peer into the jail yard, as seen in the photograph on this page.

Even when nothing was visible except a jail official posting an official notice saying the execution had taken place, large crowds still gathered at the time of a scheduled hanging.

The hanging of Peter Balcombe in Cornwall, Ont. in May 1954 attracted a boisterous crowd:

was a significant impetus (although certainly not the only one) toward the abolition of capital punishment. Truscott was sentenced to death for the murder of a classmate. His sentence was later commuted to a life sentence and in 2007 he was acquitted of the charges.

While capital punishment has been abolished in Canada, a poll taken in January 2011 by Abacus Data found that as many as two-thirds of Canadians support capital punishment, although less than half of the country wants to see it reinstated. The poll results were similar to those of a poll taken in 1978. A week prior to the poll, Prime Minister

Stephen Harper

stated that it was his personal opinion that there are times where capital punishment is appropriate, but that he did not have any plans to bring the measure back. Opposition parties challenged Harper's statement, but Abacus CEO David Coletto opined that the Prime Minister's statement was in line with his party's supporters and with public sentiment.

Regarding the death of Osama Bin Laden

, a separate poll showed that 85% of Canadians believed the American actions were justified.

, in the case United States v. Burns

, (2001), has determined that Canada should not extradite condemned persons, unless they have assurances that the foreign state will not apply the death penalty, essentially overruling Kindler v. Canada (Minister of Justice)

, (1991). This is similar to the extradition policies of other nations such as Germany

, France

, the Netherlands

, Spain

, Italy

, the United Kingdom

, Israel

, Mexico

, and Australia

, which also refuse to extradite prisoners who may be condemned to death.

In November 2007, Canada's minority

Conservative

government reversed a longstanding policy of automatically requesting clemency for Canadian citizens sentenced to capital punishment. The ongoing case of Alberta

-born Ronald Allen Smith

, who has been on death row in the United States

since 1982 after being convicted of murdering two people and who continues to seek calls for clemency from the Canadian government, prompted Canadian Public Safety Minister Stockwell Day

to announce the change in policy. Day has stated that each situation should be handled on a case-by-case basis. Smith's case resulted in a sharp divide between the Liberals and the Conservatives, with the Liberals passing a motion declaring that the government "should stand consistently against the death penalty, as a matter of principle, both in Canada and around the world." However, an overwhelming majority of Conservatives supported the change in policy.

Canada

Canada is a North American country consisting of ten provinces and three territories. Located in the northern part of the continent, it extends from the Atlantic Ocean in the east to the Pacific Ocean in the west, and northward into the Arctic Ocean...

for capital punishment

Capital punishment

Capital punishment, the death penalty, or execution is the sentence of death upon a person by the state as a punishment for an offence. Crimes that can result in a death penalty are known as capital crimes or capital offences. The term capital originates from the Latin capitalis, literally...

in nonmilitary contexts was hanging

Hanging

Hanging is the lethal suspension of a person by a ligature. The Oxford English Dictionary states that hanging in this sense is "specifically to put to death by suspension by the neck", though it formerly also referred to crucifixion and death by impalement in which the body would remain...

. The last execution in Canada was on December 11, 1962, at Toronto's Don Jail

Don Jail

The Toronto Jail is a provincial jail for remanded offenders in the city of Toronto, Ontario, Canada. It is located in the Riverdale neighbourhood on Gerrard Street East near its intersection with Broadview Avenue. It gets its nickname from the nearby Don River...

.

John Radclive

John Radclive was Canada's first professional executioner, placed on the federal payroll as a hangman by a Dominion order-in-council in 1892, on the recommendation of the justice minister Sir John Thompson: Radclive had trained under British hangman William MarwoodWilliam Marwood

William Marwood was a hangman for the British government. He developed the technique of hanging known as the "long drop".-Early life:Marwood was originally a cobbler, of Church Lane, Horncastle, Lincolnshire, England.-Executioner:...

. He can be shown to have hanged at least 69 people in Canada, although his life total was probably much higher. At his death, the Toronto Telegram said he had 150 executions. He died of alcohol-related illness in Toronto on February 26, 1911, at the age of 55.

Arthur Ellis

Arthur Ellis was the pseudonymPseudonym

A pseudonym is a name that a person assumes for a particular purpose and that differs from his or her original orthonym...

of Arthur B. English

Arthur B. English

Arthur Bartholomew English was a British man who became Canada's hangman in 1912, when he was officially offered the job. Prior to this he had been an assistant to John Radclive, a veteran of twenty years of hangings. English served in this capacity until 1935...

, a British

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

man who became Canada's official hangman

Executioner

A judicial executioner is a person who carries out a death sentence ordered by the state or other legal authority, which was known in feudal terminology as high justice.-Scope and job:...

in 1913, after Radclive's death. Ellis worked as a hangman in Canada until the botched execution of Thomasina Sarao in Montreal in 1935, in which she was decapitated.

He died in poverty in Montreal in July, 1938; and lies buried in the Mount Royal Cemetery

Mount Royal Cemetery

Opened in 1852, Mount Royal Cemetery is a 165-acre terraced cemetery on the north slope of Mount Royal in the borough of Outremont, Montreal, Quebec, Canada. The burial ground shares the mountain with the much larger adjacent Roman Catholic cemetery -- Cimetière Notre-Dame-des-Neiges...

.

The Crime Writers of Canada

Crime Writers of Canada

Crime Writers of Canada is a national organization for Canadian crime writers, founded by Howard Engel.-Arthur Ellis Awards:Its annual awards are the Arthur Ellis Awards. The award statue itself is wooden model of a hanging man. The arms and legs move when the statue's string is pulled.The award is...

present annual literary awards – the Arthur Ellis Awards

Arthur Ellis Awards

The Arthur Ellis Awards are a group of Canadian literary awards, presented annually by the Crime Writers of Canada for the best Canadian crime and mystery writing....

– named after this pseudonym. Ellis is prominently featured in the 2009 documentary Hangman's Graveyard

Hangman's Graveyard

Hangman's Graveyard is a Gemini nominated and award winning Canadian documentary which was originally broadcast in Canada on History Television on December 6, 2009. A work-in-progress screening of the film was presented at the Ontario Archaeological Society’s 36th annual symposium and as the...

.

Camille Blanchard

The executioner who worked as Camille Blanchard, a pseudonym, succeeded Ellis. Blanchard was on the Quebec government payroll as a hangman, and executed people elsewhere in the country on a piecework basis. The hangman was traditionally based in Montreal where between 1912 and 1960 the gallows at Bordeaux Prison saw more executions (85) take place than any other correctional facility in Canada.Blanchard carried out many executions (for which he was not paid) in the postwar period in Canada, such as the double hanging of Leonard Jackson and Steven Suchan of the Boyd Gang

Boyd Gang

The Boyd Gang was a notorious criminal gang based in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, named for member Edwin Alonzo Boyd. The gang was a favourite of the media at the time because of its sensational actions, which included bank robberies, jail breaks, beautiful women, gun fights, manhunts, and daring...

at the Don Jail in 1952, and Robert Raymond Cook's execution in Fort Saskatchewan, Alberta, in 1960.

History

In early years, offences such as treason

Treason

In law, treason is the crime that covers some of the more extreme acts against one's sovereign or nation. Historically, treason also covered the murder of specific social superiors, such as the murder of a husband by his wife. Treason against the king was known as high treason and treason against a...

, theft, burglary, rape, pedophilia, homosexuality, and unusual sexual practices like bestiality were considered punishable by death. Authority steadily increased the number of offences that were punishable by death in order to deter the number of crimes committed. After being hanged, authority often left the body in public, usually covered with tar so that they could preserve them from weather.

After Confederation, a revision of the statutes reduced the number of offences to only three general offences that were punishable by death: murder, rape, and treason. The only case since Confederation in which the offender received the death penalty for an offence other than murder was the Métis

Métis people (Canada)

The Métis are one of the Aboriginal peoples in Canada who trace their descent to mixed First Nations parentage. The term was historically a catch-all describing the offspring of any such union, but within generations the culture syncretised into what is today a distinct aboriginal group, with...

leader, Louis Riel

Louis Riel

Louis David Riel was a Canadian politician, a founder of the province of Manitoba, and a political and spiritual leader of the Métis people of the Canadian prairies. He led two resistance movements against the Canadian government and its first post-Confederation Prime Minister, Sir John A....

. He was convicted of high treason for his participation in the North-West Rebellion

North-West Rebellion

The North-West Rebellion of 1885 was a brief and unsuccessful uprising by the Métis people of the District of Saskatchewan under Louis Riel against the Dominion of Canada...

. In 1868, Parliament also stated that the location of the execution was to be within the confines of the prison, as opposed to the public hangings in the past. As a result, by the 1870’s, the jails had begun to build the gallows five feet from the ground with a pit underneath instead of the previous high scaffold, built level with the prison wall.

In 1950, an attempt was made to abolish capital punishment. Mr. W. Ross Thatcher moved Bill No. 2 in order to amend the Criminal Code to abolish the death penalty. However, Thatcher later withdrew it for fear of Bill No. 2 not generating positive discussion and further harming the chances of abolishment. In 1956, the Joint Committee of the House and Senate recommended the retention of capital punishment as the mandatory punishment for murder, which opened the door to the possibility of abolishment

In 1961, legislation was introduced to reclassify murder into capital or non-capital offences. A capital murder involved a planned or deliberate murder, murder during violent crimes, or the murder of a police officer

Police officer

A police officer is a warranted employee of a police force...

or prison guard. Only capital murder carried the death sentence.

Following the success of Lester Pearson and the Liberal

Liberal Party of Canada

The Liberal Party of Canada , colloquially known as the Grits, is the oldest federally registered party in Canada. In the conventional political spectrum, the party sits between the centre and the centre-left. Historically the Liberal Party has positioned itself to the left of the Conservative...

party in the 1963 federal election

Canadian federal election, 1963

The Canadian federal election of 1963 was held on April 8 to elect members of the Canadian House of Commons of the 26th Parliament of Canada. It resulted in the defeat of the minority Progressive Conservative government of Prime Minister John Diefenbaker.-Overview:During the Tories' last year in...

, and through the successive governments of Pierre Trudeau

Pierre Trudeau

Joseph Philippe Pierre Yves Elliott Trudeau, , usually known as Pierre Trudeau or Pierre Elliott Trudeau, was the 15th Prime Minister of Canada from April 20, 1968 to June 4, 1979, and again from March 3, 1980 to June 30, 1984.Trudeau began his political career campaigning for socialist ideals,...

, the federal cabinet

Cabinet of Canada

The Cabinet of Canada is a body of ministers of the Crown that, along with the Canadian monarch, and within the tenets of the Westminster system, forms the government of Canada...

commuted all death sentences as a matter of policy. Hence, the de facto abolition of the death penalty in Canada occurred in 1963, with legal abolition a formality. On November 30, 1967, Bill C-168 was passed creating a five-year moratorium

Moratorium (law)

A moratorium is a delay or suspension of an activity or a law. In a legal context, it may refer to the temporary suspension of a law to allow a legal challenge to be carried out....

on the use of the death penalty, except for murder

Murder

Murder is the unlawful killing, with malice aforethought, of another human being, and generally this state of mind distinguishes murder from other forms of unlawful homicide...

s of police and corrections officers. On January 26, 1973, after the expiration of the five-year experiment, the Solicitor General of Canada continued the partial ban on capital punishment, which would eventually lead to the abolition of capital punishment. On July 14, 1976, Bill C-84 was passed by a narrow margin of 130:124 in a free vote, resulting in the de jure

De jure

De jure is an expression that means "concerning law", as contrasted with de facto, which means "concerning fact".De jure = 'Legally', De facto = 'In fact'....

abolition of the death penalty, except for certain offences under the National Defence Act

National Defence Act

The National Defence Act is the primary enabling legislation for organizing and funding Canada's military....

. These were removed in 1998.

First-degree murder, which before abolition was the offence of capital murder, now carries a mandatory life sentence without eligibility

Eligibility

Eligibility may refer to:* The right to run for office , sometimes called passive suffrage or voting eligibility* Desirability as a marriage partner, as in the term eligible bachelor...

for parole

Parole

Parole may have different meanings depending on the field and judiciary system. All of the meanings originated from the French parole . Following its use in late-resurrected Anglo-French chivalric practice, the term became associated with the release of prisoners based on prisoners giving their...

until the person has served 25 years of the sentence.

Military executions

During the First World WarWorld War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

, 25 Canadian soldiers were executed. Most were shot for service offences such as desertion

Desertion

In military terminology, desertion is the abandonment of a "duty" or post without permission and is done with the intention of not returning...

and cowardice

Cowardice

Cowardice is the perceived failure to demonstrate sufficient mental robustness and courage in the face of a challenge. Under many military codes of justice, cowardice in the face of combat is a crime punishable by death...

, but two executions were for murder

Murder

Murder is the unlawful killing, with malice aforethought, of another human being, and generally this state of mind distinguishes murder from other forms of unlawful homicide...

. For details of these see List of Canadian soldiers executed during World War I.

One Canadian soldier, Pte. Harold Pringle

Harold Pringle

Harold Joseph Pringle was the only soldier of the Canadian Army to be executed during the Second World War for military crimes.Pringle enlisted in the Canadian Army with his father...

, was executed during the Second World War for murder.

Last people executed in Canada

The last two people executed in Canada were Ronald TurpinRonald Turpin

On December 10, 1962 Ronald Turpin, 29, was one of the two last people to be executed in the Dominion of Canada. The other prisoner was Arthur Lucas who was executed alongside Turpin at the Toronto Jail. Turpin had been convicted of the murder of Metropolitan Toronto police officer Frederick Nash...

, 29, and Arthur Lucas

Arthur Lucas

Arthur Lucas, originally from the U.S. state of Georgia, was one of the two last people to be executed in Canada, on December 11, 1962. Lucas had been convicted of the murder of an undercover narcotics agent from Detroit...

, 54, convicted for separate murders, at 12:02 am on December 11, 1962 at the Don Jail

Don Jail

The Toronto Jail is a provincial jail for remanded offenders in the city of Toronto, Ontario, Canada. It is located in the Riverdale neighbourhood on Gerrard Street East near its intersection with Broadview Avenue. It gets its nickname from the nearby Don River...

in Toronto

Toronto

Toronto is the provincial capital of Ontario and the largest city in Canada. It is located in Southern Ontario on the northwestern shore of Lake Ontario. A relatively modern city, Toronto's history dates back to the late-18th century, when its land was first purchased by the British monarchy from...

.

The last woman to be hanged in Canada was Marguerite Pitre on January 9, 1953, for her part in the Albert Guay affair.

Method

Before travelling to the New World, EnglandEngland

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

and France

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

had experimented with a wide range of different methods of punishment such as burning at the stake, boiling in oil, beheading, pressing to death, and the guillotine, for decades. Using the philosophy that the death penalty must inflict pain upon the offender, the methods of capital punishment tended to be gruesome and violent. Thus, onlookers took it upon themselves not to commit the crimes that caused the offender so much agony.

The most common method of execution eventually became hanging

Hanging

Hanging is the lethal suspension of a person by a ligature. The Oxford English Dictionary states that hanging in this sense is "specifically to put to death by suspension by the neck", though it formerly also referred to crucifixion and death by impalement in which the body would remain...

. The first method was “hoisting” in which a rope would be thrown over a beam and the convicted person would then be hoisted into the air by others pulling on the rope. The slip knot would then tightly close around the neck until strangulation. A variation of this included the person with a rope around their neck to stand on a cart and then it would be pushed from under them. This led to the development of suspension in which “the drop” caused by jerking something from underneath the offender became the main component of the execution. Executioners experimented with the length of the rope for the drop. They specifically began to discover new ways of causing instant death upon hanging. In 1872, the length of a drop extended to nearly five-feet which dislocated the neck perfectly. Almost one year later, the length of the drop was extended to seven feet.

The majority of offenders put to death by Canadian civilian authorities were executed by the "long drop" technique of hanging

Hanging

Hanging is the lethal suspension of a person by a ligature. The Oxford English Dictionary states that hanging in this sense is "specifically to put to death by suspension by the neck", though it formerly also referred to crucifixion and death by impalement in which the body would remain...

developed in the United Kingdom

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

by William Marwood

William Marwood

William Marwood was a hangman for the British government. He developed the technique of hanging known as the "long drop".-Early life:Marwood was originally a cobbler, of Church Lane, Horncastle, Lincolnshire, England.-Executioner:...

. This method ensured that the prisoner's neck was broken instantly at the end of the drop, resulting in the prisoner dying of asphyxia

Asphyxia

Asphyxia or asphyxiation is a condition of severely deficient supply of oxygen to the body that arises from being unable to breathe normally. An example of asphyxia is choking. Asphyxia causes generalized hypoxia, which primarily affects the tissues and organs...

while unconscious, which was considered more humane than the slow death by strangulation which often resulted from the previous "short drop" method. The short drop sometimes gave a period of torture before death finally took place.

Early in his career, John Radclive persuaded several sheriffs in Ontario and Quebec to let him use an alternative method in which the condemned person was jerked into the air. A gallows of this type was used for the execution of Robert Neil at Toronto’s Don Jail

Don Jail

The Toronto Jail is a provincial jail for remanded offenders in the city of Toronto, Ontario, Canada. It is located in the Riverdale neighbourhood on Gerrard Street East near its intersection with Broadview Avenue. It gets its nickname from the nearby Don River...

on February 29, 1888:

The old plan of a “drop” was discarded for a more merciful machine, by which the prisoner is jerked up from a platform on the ground level by a weight of 280 lbs, which is suspended by an independent rope pending the execution … At the words ‘Forgive us our trespasses,’ the executioner drove his chisel against the light rope that held the ponderous iron at the other end of the noose, and in an instant the heavy weight fell with a thud, and the pinioned body was jerked into the air and hung dangling between the rough posts of the scaffold.

The hanging of Reginald Birchall in Woodstock, Ont. in November 1890 seems to be the last time a device of this kind was used. Radclive had first been exposed to executions as a Royal Navy

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Founded in the 16th century, it is the oldest service branch and is known as the Senior Service...

seaman helping with shipboard hangings of pirates in the South China Sea, and it is possible he was trying to approximate something similar to hanging a man on a ship's yardarm. After Birchall's hanging, Radclive used the traditional long drop method, as did his successors.

While hanging was a relatively humane method of execution under ideal conditions with an expert executioner, mistakes could happen. Condemned prisoners were decapitated by accident at Headingley Jail in Manitoba and Bordeaux Jail in Montreal, and a prisoner at the Don Jail in Toronto hit the floor of the room below and was strangled by the hangman.

Some Canadian jails - such as those in Toronto, Ontario, Headingley, Manitoba, and Fort Saskatchewan, Alberta - had permanent indoor execution facilities, but more typically offenders were hanged on a scaffold built for the occasion in the jail yard.

Military prisoners sentenced to death in Canada were shot by firing squad

Execution by firing squad

Execution by firing squad, sometimes called fusillading , is a method of capital punishment, particularly common in the military and in times of war.Execution by shooting is a fairly old practice...

.

Executions and the public

At least in theory, hangings were supposed to take place in private after the 1870s. However, small county jails, which saw a hanging perhaps every few decades, were not always able to organize a fully private execution, and members of what MP Agnes MacphailAgnes Macphail

Agnes Campbell Macphail was the first woman to be elected to the Canadian House of Commons, and one of the first two women elected to the Legislative Assembly of Ontario...

described as the "morbid public" came to see something of the spectacle.

At the hanging of Stanislaus Lacroix in Hull, Quebec in 1902, for example, onlookers climbed buildings and telephone poles to peer into the jail yard, as seen in the photograph on this page.

Even when nothing was visible except a jail official posting an official notice saying the execution had taken place, large crowds still gathered at the time of a scheduled hanging.

The hanging of Peter Balcombe in Cornwall, Ont. in May 1954 attracted a boisterous crowd:

The canvas-covered top of the gallows was plainly visible from the street. The crowd, many of them teenagers including many young girls, was in a holiday mood, shooting off firecrackers, joking and laughing for more than two hours before the execution took place. Several times, police details had to clear the streets so vehicles could pass as the onlookers pressed forward for better vantage points.

Public opinion

Amongst the reasons cited for banning capital punishment in Canada were fears about wrongful convictions, concerns about the state taking people's lives, and uncertainty about the death penalty's role as a deterrent for crime. The 1959 conviction of 14-year-old Steven TruscottSteven Truscott

Steven Murray Truscott is a Canadian man who was sentenced to death in 1959, when he was a 14-year old student, for the murder of classmate Lynne Harper...

was a significant impetus (although certainly not the only one) toward the abolition of capital punishment. Truscott was sentenced to death for the murder of a classmate. His sentence was later commuted to a life sentence and in 2007 he was acquitted of the charges.

While capital punishment has been abolished in Canada, a poll taken in January 2011 by Abacus Data found that as many as two-thirds of Canadians support capital punishment, although less than half of the country wants to see it reinstated. The poll results were similar to those of a poll taken in 1978. A week prior to the poll, Prime Minister

Prime Minister of Canada

The Prime Minister of Canada is the primary minister of the Crown, chairman of the Cabinet, and thus head of government for Canada, charged with advising the Canadian monarch or viceroy on the exercise of the executive powers vested in them by the constitution...

Stephen Harper

Stephen Harper

Stephen Joseph Harper is the 22nd and current Prime Minister of Canada and leader of the Conservative Party. Harper became prime minister when his party formed a minority government after the 2006 federal election...

stated that it was his personal opinion that there are times where capital punishment is appropriate, but that he did not have any plans to bring the measure back. Opposition parties challenged Harper's statement, but Abacus CEO David Coletto opined that the Prime Minister's statement was in line with his party's supporters and with public sentiment.

Regarding the death of Osama Bin Laden

Death of Osama bin Laden

Osama bin Laden, then head of the Islamist militant group al-Qaeda, was killed in Pakistan on May 2, 2011, shortly after 1 a.m. local time by a United States special forces military unit....

, a separate poll showed that 85% of Canadians believed the American actions were justified.

Canadian policy and capital punishment in foreign countries

The Supreme Court of CanadaSupreme Court of Canada

The Supreme Court of Canada is the highest court of Canada and is the final court of appeals in the Canadian justice system. The court grants permission to between 40 and 75 litigants each year to appeal decisions rendered by provincial, territorial and federal appellate courts, and its decisions...

, in the case United States v. Burns

United States v. Burns

United States v. Burns [2001] 1 S.C.R. 283, 2001 SCC 7, was a decision by the Supreme Court of Canada in which it was found that extradition of individuals to places where they may face the death penalty is a breach of fundamental justice under section 7 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms...

, (2001), has determined that Canada should not extradite condemned persons, unless they have assurances that the foreign state will not apply the death penalty, essentially overruling Kindler v. Canada (Minister of Justice)

Kindler v. Canada (Minister of Justice)

Kindler v. Canada was a landmark decision of the Supreme Court of Canada where it was held that the government policy that allowed for extradition of convicted criminals to a country where they may face the death penalty was valid under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms...

, (1991). This is similar to the extradition policies of other nations such as Germany

Germany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

, France

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

, the Netherlands

Netherlands

The Netherlands is a constituent country of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, located mainly in North-West Europe and with several islands in the Caribbean. Mainland Netherlands borders the North Sea to the north and west, Belgium to the south, and Germany to the east, and shares maritime borders...

, Spain

Spain

Spain , officially the Kingdom of Spain languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Spain's official name is as follows:;;;;;;), is a country and member state of the European Union located in southwestern Europe on the Iberian Peninsula...

, Italy

Italy

Italy , officially the Italian Republic languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Italy's official name is as follows:;;;;;;;;), is a unitary parliamentary republic in South-Central Europe. To the north it borders France, Switzerland, Austria and...

, the United Kingdom

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

, Israel

Israel

The State of Israel is a parliamentary republic located in the Middle East, along the eastern shore of the Mediterranean Sea...

, Mexico

Mexico

The United Mexican States , commonly known as Mexico , is a federal constitutional republic in North America. It is bordered on the north by the United States; on the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; on the southeast by Guatemala, Belize, and the Caribbean Sea; and on the east by the Gulf of...

, and Australia

Australia

Australia , officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country in the Southern Hemisphere comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. It is the world's sixth-largest country by total area...

, which also refuse to extradite prisoners who may be condemned to death.

In November 2007, Canada's minority

Minority government

A minority government or a minority cabinet is a cabinet of a parliamentary system formed when a political party or coalition of parties does not have a majority of overall seats in the parliament but is sworn into government to break a Hung Parliament election result. It is also known as a...

Conservative

Conservative Party of Canada

The Conservative Party of Canada , is a political party in Canada which was formed by the merger of the Canadian Alliance and the Progressive Conservative Party of Canada in 2003. It is positioned on the right of the Canadian political spectrum...

government reversed a longstanding policy of automatically requesting clemency for Canadian citizens sentenced to capital punishment. The ongoing case of Alberta

Alberta

Alberta is a province of Canada. It had an estimated population of 3.7 million in 2010 making it the most populous of Canada's three prairie provinces...

-born Ronald Allen Smith

Ronald Allen Smith

Ronald Allen Smith is a Canadian man who was sentenced to death in Montana for murdering two people. As of 2011, Smith is one of two prisoners on Montana's death row...

, who has been on death row in the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

since 1982 after being convicted of murdering two people and who continues to seek calls for clemency from the Canadian government, prompted Canadian Public Safety Minister Stockwell Day

Stockwell Day

Stockwell Burt Day, Jr., PC, MP is a former Canadian politician, and a member of the Conservative Party of Canada. He is a former cabinet minister in Alberta, and a former leader of the Canadian Alliance. Day was MP for the riding of Okanagan—Coquihalla in British Columbia and the president of...

to announce the change in policy. Day has stated that each situation should be handled on a case-by-case basis. Smith's case resulted in a sharp divide between the Liberals and the Conservatives, with the Liberals passing a motion declaring that the government "should stand consistently against the death penalty, as a matter of principle, both in Canada and around the world." However, an overwhelming majority of Conservatives supported the change in policy.

See also

- Albert Guay

- Canadian Coalition Against the Death PenaltyCanadian Coalition Against the Death PenaltyThe Canadian Coalition Against the Death Penalty is a not-for-profit organisation which was co-founded by Tracy Lamourie and Dave Parkinson of the Greater Toronto Area...

- List of revoked death sentences in Canada

- Madame le CorbeauMadame le CorbeauMarguerite Pitre , also known as Marguerite Ruest-Pitre and as "Madame le Corbeau" because she always wore black clothes, was a Canadian conspirator in a mass murder carried out by the bombing of an airliner...