Allied-administered Austria

Encyclopedia

The Allied occupation of Austria lasted from 1945 to 1955. Austria

had been regarded by Nazi Germany

as a constituent part of the German state, but in 1943 the Allied powers agreed in the Declaration of Moscow that it would be regarded as the first victim of Nazi aggression, and treated as a liberated and independent country after the war.

In the immediate aftermath of the war, Austria, like Germany

, was divided into four occupation zones and jointly occupied by the United States

, Soviet Union

, United Kingdom

and France

. Vienna

, like Berlin

, was similarly subdivided and the central district administered jointly by the Allied Control Council

.

Whereas Germany was formally divided into East and West Germany in 1949, Austria remained under joint occupation until 1955; its status became a controversial subject in the Cold War

until the warming of relations known as the Khrushchev Thaw

. After Austrian promises of perpetual neutrality, Austria was accorded full independence on 12 May 1955 and the last occupation troops left the country on 25 October the same year.

's troops crossed the former Austrian border at Klostermarienberg in Burgenland

. On April 3, at the beginning of the Vienna Offensive

, Austrian politician Karl Renner

, then living in southern Lower Austria

, established contact with the Soviets. Joseph Stalin

had already assembled a future puppet government of Austrian communists in exile, but Tolbukhin's telegram changed Stalin's mind in favor of Renner.

On April 20, the Soviets, acting without asking their Western allies, instructed Renner to form the provisional government of Austria. Seven days later Renner's cabinet took office, declared the independence of Austria from Nazi Germany

and called for the creation of a democratic state along the lines of the First Republic

. Soviet acceptance of Renner was not an isolated episode; their officers re-established district administrations and appointed local mayors, frequently following the advice of the locals, even before the battle was over.

Renner and his ministers were guarded and watched by NKVD

bodyguards. One-third of State Chancellor Renner's cabinet, including crucial seats of the Secretary of State for the Interior

and the Secretary of State for Education

, was staffed by Austrian Communists. The Western allies suspected the usual Soviet pattern of setting up puppet state

s and did not recognize Renner. The British were particularly hostile; even Harry Truman

, who personally believed that Renner was a trustworthy politician rather than a token front for the Kremlin, denied him recognition. But Renner had secured inter-party control by designating two Under-Secretaries of State in each of the ministries, being appointed by the two parties not placing the Secretary of State there.

As soon as Hitler's armies were pushed back into Germany, the Red Army

and the NKVD

began to comb the captured territories. By May 23 they reported arrests of 268 former Red Army men, 1208 Wehrmacht

men and 1,655 civilians. In the following weeks the British surrendered over forty thousand Cossacks who had fled to Western Austria to the Soviet authorities and certain death. In July and August, the Soviets brought in four regiments of NKVD troops

to "mop up" Vienna and seal the Czech border.

The Red Army had lost 17,000 lives in the Battle of Vienna and brought freedom from Nazism to the country. But the reputation of the Soviet soldiers was immediately ruined by the vast amount of sexual violence against women, which occurred in the first days and weeks after the Soviet victory. Repressions against civilians harmed Red Army reputation to such an extent that on September 28, 1945 Moscow issued an order forbidding violent interrogations. Red Army morale fell as soldiers prepared to be sent home; replacement of combat units with Ivan Konev

's permanent occupation force

only marginally improved the Austrians' suffering. Throughout 1945 and 1946, all levels of Soviet command tried, in vain, to contain desertion and plunder by rank and file. According to Austrian police records for 1946, "men in Soviet uniform", usually drunk, accounted for more than 90% of registered crime (American soldiers: 5 to 7%). Yet, at the same time, the Soviet governors resisted expansion and arming of Austrian police force.

The French troops crossed the Austrian border on April 29, followed by the Americans and finally the British on May 8. Until the end of July 1945 none of the Western allies had first-hand intelligence from Eastern Austria (likewise, Renner's cabinet knew practically nothing about conditions in the West).

The French troops crossed the Austrian border on April 29, followed by the Americans and finally the British on May 8. Until the end of July 1945 none of the Western allies had first-hand intelligence from Eastern Austria (likewise, Renner's cabinet knew practically nothing about conditions in the West).

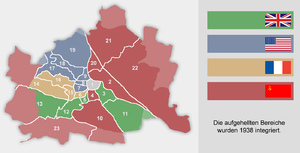

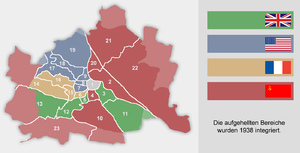

On July 9, 1945 the Allies agreed on the borders of their occupation zones in Austria. Vorarlberg

and North Tyrol

were assigned to the French Zone; Salzburg

and Upper Austria

south of the Danube to the American Zone; East Tyrol

, Carinthia

and Styria to the British Zone; and Burgenland

, Lower Austria

, and the Mühlviertel

area of Upper Austria, north of the Danube, to the Soviet Zone. The occupation zones were assigned so that the French and American zones bordered those countries' respective zones in Germany and the Soviet zone bordered future Warsaw Pact

states. Vienna

was divided among all four Allies. The historical center of Vienna

was declared an international zone, in which occupation forces changed every month. Movement of occupation troops ("zone swap") continued until the end of July.

The first Americans arrived in Vienna in the end of July 1945, when the Soviets were pressing Renner to surrender Austrian oil field

s. Americans objected and blocked the deal but ultimately the Soviets assumed control over Austrian oil in their zone. The British arrived only in September. The Allied Council of four military governors convened for its first meeting in Vienna on September 12, 1945. It refused to recognize Renner's claims for a national government but did not prevent him from extending influence into the Western zones. Renner appointed vocal anti-communist Karl Gruber

to represent Austria as its Foreign Minister and tried to reduce Communist influence. On October 20, 1945, Renner's reformed cabinet was recognized by the Western allies and received a go-ahead for the first legislative election.

was a blow for the Communist Party of Austria

which received less than 5% of the vote. The coalition of Christian Democrats

(ÖVP

) and Social Democrats

(SPÖ

), backed by 90% of the votes, assumed control over the cabinet and offered the seat of Federal Chancellor

to Christian Democrat Julius Raab

. The Soviets veto

ed Raab, due to his political role in the 1930s. Instead President Karl Renner, with the consent of parliament, appointed Leopold Figl

who was just barely acceptable to the Soviets. They responded with massive and coordinated expropriation of Austrian economic potential.

The Potsdam Agreement

allowed confiscation of "German external assets" in Austria, and the Soviets used the vagueness of this definition to the full. In less than a year they dismantled and shipped to the East industrial equipment valued at around 500 million U.S. dollars. American High Commissioner Mark W. Clark vocally resisted Soviet expansionist intentions, and his reports to Washington, along with George F. Kennan

's The Long Telegram

, supported Truman's tough stance against the Soviets. Thus, according to Bischof, the Cold War

in Austria began in the spring of 1946, one year before the outbreak of the global Cold War.

On June 28, 1946, the Allies signed the Second Control Agreement that loosened their dominance over the Austrian government. Parliament of Austria

was de facto

relieved of Allied control. From now on its decision could be overturned only by unanimous vote by all four Allies. The Soviet veto

es against Austrian laws were routinely voided by the Western opposition. For the next nine years the country was gradually emancipated from foreign control, and evolved from a "nation under tutelage

" to full independence. The government of Austria possessed its own independent vision of the future, reacting to adverse circumstances and at times turning them to their own benefit. First allied talks on Austrian independence were held in January 1947, and deadlocked over the issue of "German assets" in Soviet possession.

Coincidentally with the Second Control Agreement, the Soviets changed their economic policy from outright plunder to running expropriated Austrian businesses for a profit. Austrian communists advised Stalin to nationalize the whole economy, but he deemed the proposal to be too radical. Between February and June 1946, the Soviets expropriated hundreds of businesses left in their zone. On June 27, 1946, they amalgamated these assets into the USIA

, a conglomerate

of over 400 enterprises. It controlled not more than 5% of Austrian economic output but possessed substantial, or even monopolistic, share in glass, steel, oil and transportation industries. The USIA was weakly integrated with the rest of Austrian economy: its products were primarily shipped to the East, its profits de-facto confiscated and its taxes left unpaid by the Soviets. The Austrian government refused to recognize USIA legal title over its possessions; in retaliation, the USIA refused to pay Austrian taxes and tariffs. This competitive advantage helped to keep USIA enterprises afloat despite their mounting obsolescence. The Soviets had no intention to reinvest their profits, and USIA assets gradually decayed and lost their competitive edge. The Austrian government feared paramilitary communist gangs sheltered by the USIA and scorned it for being "an economy of exploitation in colonial style." The economy of the Soviet zone eventually reunited with the rest of the country.

South Tyrol

, a disputed territory in the Alps

, was returned to Italy. The "thirty-second decision" of the Council of Foreign Ministers

to grant South Tyrol to Italy (September 4, 1945) disregarded popular opinion in Austria and the possible effects of a forced repatriation

of 200,000 German-speaking Tyroleans. The decision was motivated largely by the British desire to reward Italy

, a country far more important for the containment

of world communism. Renner's objections came in too late and carried too little weight to have effect. Popular and official protests continued through 1946. The signatures of 150,000 South Tyroleans did not alter the decision. South Tyrol is today an Italian autonomous province (Bolzano/Bozen

) with a German-speaking majority.

remaining below 2000 calories until the end of 1947. 65% of Austrian agricultural output and nearly all oil concentrated in the Soviet zone, complicating the Western Allies' task of feeding the population in their own zones.

From March 1946 to June 1947, 64% of these rations were provided by the UNRRA

. Heating depended on supplies of German coal shipped by the U.S. on lax credit terms. Draught of 1946 further depressed farm output and hydroelectric power generation. Figl's government, the Chambers of Labor, Trade and Agriculture, and the Austrian Trade Union Federation

(ÖGB) temporarily resolved the crisis in favor of tight regulation of food and labor markets. Wage increases were limited and locked to commodity prices through annual price-wage agreements. The negotiations set a model of building consensus

between elected and non-elected political elites that became the basis of post-war Austrian democracy, known as Austrian Social Partnership and Austro-corporatism

.

The severe winter of 1946–1947 was followed by the disastrous summer of 1947, when potato

harvest barely made 30% of pre-war output. Food shortages of 1947 were aggravated by the withdrawal of UNRRA aid, the spiraling inflation and the demoralizing failure of State Treaty talks. In April 1947, the government was unable to distribute any rations at all, and on May 5 Vienna was shaken by a violent food riot. Unlike earlier popular protests, this time the demonstrators, led by the Communists, called to curb the westernization of Austrian politics. In August, food riot in Bad Ischl

turned into a pogrom

of local Jews. In November, food shortage sparked workers' strikes in British-occupied Styria. Figl's government declared that the food riots were a failed communist putsch

, although later historians refuted this statement as an exaggeration.

In June 1947, the month when the UNRRA stopped shipments of food to Austria, the extent of the food crisis compelled the U.S. government to issue 300 million dollars in food aid. In the same month Austria was invited to discuss its participation in the Marshall Plan

. Direct aid and subsidies helped Austria to survive the hunger of 1947. On the other hand, they depressed food prices and thus discouraged local farmers, delaying the rebirth of Austrian agriculture.

of Marshall Plan aid in March 1948. Austrian heavy industry (or what was left of it) concentrated around Linz

, in the American zone, and in British-occupied Styria. Their products were in high demand in post-war Europe. Quite naturally, the administrators of the Marshall Plan channeled available financial aid into heavy industry controlled by the American and British forces. American military and political leaders made no secret of their intentions: Geoffrey Keyes

said that "we cannot afford to let this key area (Austria) fall under exclusive influence of the Soviet Union." Marshall Plan was deployed primarily against the Soviet zone but it was not completely excluded: it received 8% of Marshall plan investments (compared to 25% of food and other physical commodities). Austrian government regarded financial aid to the Soviet zone as a lifeline holding the country together. This was the only case when Marshall Plan funds were distributed in Soviet-occupied territories.

The Marshall Plan was not universally popular, especially in its initial phase. It benefited some trades such as metallurgy but depressed others such as agriculture. Heavy industries quickly recovered, from 74.7% of pre-war output in 1948 to 150.7% in 1951. American planners deliberately neglected consumer goods industries, construction trades and small business. Their workers, almost half of Austrian industrial workforce, suffered from rising unemployment. In 1948–1949, a substantial share of Marshall Plan funds allocated to Austria was used to subsidize imports of food. American money, effectively, raised real wage

s of Austrian workers: grain price in Austria was at about one-third of the world price, while local agriculture remained in ruin. Marshall Plan aid gradually removed many of the causes of popular unrest that shook the country in 1947, but Austria remained dependent on food imports.

The second stage of the Marshall Plan, which began in 1950, concentrated on productivity

of the economy. According to Michael J. Hogan

, "in the most profound sense, it involved the transfer of attitudes, habits and values as well, indeed a whole way of life that Marshall planners associated with progress in the marketplace of politics and social relationships as much as they did with industry and agriculture." The program, as instructed by American lawmakers, targeted improvement in factory-level productivity, labor-management relations, free trade unions and introduction of modern business practices. The Economic Cooperation Administration

, which operated until December 1951, distributed around 300 million dollars in technical assistance and attempted steering the Austrian social partnership (political parties, labor unions, business associations and executive government) in favor of productivity and growth instead of redistribution and consumption.

Their efforts were thwarted by the Austrian practice of making decisions behind closed doors. The Americans struggled to change it in favor of open, public discussion. They took a strong anti-cartel

stance, appreciated by the Socialists, and pressed the Austrian government to remove anti-competition legislation. But ultimately they were responsible for the creation of the vast monopolistic public sector of Austrian economy (and thus politically benefiting the Socialists).

According to Bischof, "no European nation benefited more from Marshall Plan than Austria." Austria received nearly a billion U.S. dollars through Marshall Plan, and half a billion in humanitarian aid. The Americans also refunded to Austria all occupation costs charged in 1945–1946, around 300 million. In 1948-1949 Marshall Plan aid contributed 14% of Austrian national income, the highest ratio of all involved countries. Per capita, aid amounted to 132 dollars compared to 19 dollars for the Germans. But Austria also paid more war reparations

per capita than any other Axis state

or territory. Total war reparations taken by the Soviet Union including withdrawn USIA profits, looted property and the final settlement agreed in 1955, are estimated between 1.54 and 2.65 billion U.S. dollars (Eisterer: 2 to 2.5 billion).

. They set up and filled emergency food dumps, and prepared to airlift

supplies to Vienna while the Austrian government created a backup base in Salzburg

. The American command secretly trained the soldiers of underground Austrian military at a rate of two hundred men a week. The Gendarmerie

knowingly hired Wehrmacht

veterans and VdU

members; the denazification

of Austria's 537,000 registered Nazis had largely ended in 1948.

Austrian communists appealed to Stalin to partition their country along the German model, but in February 1948 Andrei Zhdanov

vetoed the idea: Austria had more value as a bargaining chip than as another unstable client state. The continuing talks on Austrian independence stalled in 1948 but progressed to a "near breakthrough" in 1949: the Soviets lifted most of their objections, and the Americans suspected foul play. The Pentagon

was convinced that the withdrawal of Western troops would leave the country open to Soviet invasion of the Czech model

. Clark insisted that before their departure the United States must secretly train and arm the core of a future Austrian military. Serious secret training of the Austrian forces (the B-Gendarmerie) began in 1950 but soon stalled due to US defense budget cuts in 1951. Austrian gendarmes were trained primarily as an anti-coup police force, but they also studied Soviet combat practice and counted on cooperation with the Yugoslavs

in case of an open Soviet invasion.

Although in the fall of 1950 the Western powers replaced their military representatives with civilian diplomats, strategic situation became gloomier than ever. The Korean War

experience persuaded Washington that Austria may become "Europe's Korea" and sped up rearmament of the "secret ally". International tension was coincident with a severe internal economic and social crisis. The planned withdrawal of American food subsidies spelled a sharp drop in real wage

s for all Austrians. The government and the unions deadlocked in negotiations, and gave the Austrian communists the opportunity to organize the 1950 Austrian general strikes

which became the gravest threat to Austria since the 1947 food riots. The communists stormed and took over ÖGB

offices, disrupted railroad traffic but failed to recruit sufficient public support and had to admit defeat. The Soviets and the Western allies did not dare to actively intervene in the strikes. The strike intensified militarization of Western Austria, this time with active input from France

and the CIA

. Despite the strain of Korean War, by the end of 1952 the American "Stockpile A" (A for Austria) in France and Germany amassed 227 thousand tons of materiel

earmarked for Austrian armed forces.

defused the standoff in Austria, and the country was rapidly, but not completely, demilitarized. After the Soviet Union had relieved Austria of the need to pay for the cost of their reduced army of 40,000 men, the British and French followed suit and reduced their forces to a token presence. Finally, the Soviets replaced their military governor with a civilian ambassador

. The former border between Eastern and Western Austria became a mere demarcation line

.

Chancellor Julius Raab

, elected in April 1953, removed pro-Western foreign minister Gruber and steered Austria to a more neutral policy. Raab carefully probed the Soviets about resuming the talks on Austrian independence, but until February 1955 it remained contingent on a solution to the larger German problem. The Western strategy of rearming West Germany, formulated in the Paris Agreement

, was unacceptable to the Soviets. They responded with a counter-proposal for a pan-European security system that, they said, could speed up reunification of Germany, and again the West suspected foul play. Eisenhower

, in particular, had "an utter lack of confidence in the reliability and integrity of the men in the Kremlin... the Kremlin is pre-empting the right to speak for the small nations of the world"

In January 1955, Soviet diplomats Andrey Gromyko, Vladimir Semenov and Georgy Pushkin secretly advised Vyacheslav Molotov

to unlink Austrian and German issues, expecting that the new talks on Austria would delay ratification of the Paris Agreement. Molotov publicly announced the new Soviet initiative on 8 February. He put forward three conditions for Austrian independence: neutrality, no foreign military bases and guarantees against a new Anschluss

.

had set for Schuschnigg in 1938. Anthony Eden

and others wrote that the Moscow initiative was merely a cover-up for another incursion into German matters. The West erroneously thought that the Soviets valued Austria primarily as a military asset, when in reality it was a purely political issue. Austria's military significance has been largely devalued by the end of the Soviet-Yugoslav conflict and the upcoming signing of the Warsaw Pact

.

These fears did not materialize, and Raab's visit to Moscow (April 12-15) was a breakthrough. Moscow agreed that Austria would be free not later than 31 December. Austrians agreed to pay for the "German assets" and oil fields left by the Soviets, mostly in kind; "the real prize was to be neutrality on the Swiss model." Molotov also promised release and repatriation of Austrians imprisoned in the Soviet Union.

Western powers were stunned; Wallinger reported to London that the deal "was far too good to be true, to be honest". But it proceeded as had been agreed in Moscow and on 15 May 1955 Antoine Pinay

, Harold MacMillan

, Molotov, John Foster Dulles

and Figl signed the Austrian State Treaty

. It came into force on July 27 and on 25 October the country was free of occupying troops. The Soviets left to the new Austrian government a symbolic cache of small arms, artillery and T-34

tanks; the Americans left a far greater gift of "Stockpile A" assets. The only person upset about the outcome was Konrad Adenauer

, who called the affair "die ganze Österreichische Schweinerei" ("the whole Austrian scandal") and threatened the Austrians with "sending Hitler's remains home to Austria".

Austria

Austria , officially the Republic of Austria , is a landlocked country of roughly 8.4 million people in Central Europe. It is bordered by the Czech Republic and Germany to the north, Slovakia and Hungary to the east, Slovenia and Italy to the south, and Switzerland and Liechtenstein to the...

had been regarded by Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

as a constituent part of the German state, but in 1943 the Allied powers agreed in the Declaration of Moscow that it would be regarded as the first victim of Nazi aggression, and treated as a liberated and independent country after the war.

In the immediate aftermath of the war, Austria, like Germany

Germany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

, was divided into four occupation zones and jointly occupied by the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

, Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

, United Kingdom

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

and France

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

. Vienna

Vienna

Vienna is the capital and largest city of the Republic of Austria and one of the nine states of Austria. Vienna is Austria's primary city, with a population of about 1.723 million , and is by far the largest city in Austria, as well as its cultural, economic, and political centre...

, like Berlin

Berlin

Berlin is the capital city of Germany and is one of the 16 states of Germany. With a population of 3.45 million people, Berlin is Germany's largest city. It is the second most populous city proper and the seventh most populous urban area in the European Union...

, was similarly subdivided and the central district administered jointly by the Allied Control Council

Allied Control Council

The Allied Control Council or Allied Control Authority, known in the German language as the Alliierter Kontrollrat and also referred to as the Four Powers , was a military occupation governing body of the Allied Occupation Zones in Germany after the end of World War II in Europe...

.

Whereas Germany was formally divided into East and West Germany in 1949, Austria remained under joint occupation until 1955; its status became a controversial subject in the Cold War

Cold War

The Cold War was the continuing state from roughly 1946 to 1991 of political conflict, military tension, proxy wars, and economic competition between the Communist World—primarily the Soviet Union and its satellite states and allies—and the powers of the Western world, primarily the United States...

until the warming of relations known as the Khrushchev Thaw

Khrushchev Thaw

The Khrushchev Thaw refers to the period from the mid 1950s to the early 1960s, when repression and censorship in the Soviet Union were partially reversed and millions of Soviet political prisoners were released from Gulag labor camps, due to Nikita Khrushchev's policies of de-Stalinization and...

. After Austrian promises of perpetual neutrality, Austria was accorded full independence on 12 May 1955 and the last occupation troops left the country on 25 October the same year.

Soviet rule and Austrian government

On March 29, 1945 Soviet commander Fyodor TolbukhinFyodor Tolbukhin

Fyodor Ivanovich Tolbukhin was a Soviet military commander.-Biography:Tolbukhin was born into a peasant family in the province of Yaroslavl, north-east of Moscow. He volunteered for the Imperial Army in 1914 at the outbreak of World War I. He was steadily promoted, advancing from private to...

's troops crossed the former Austrian border at Klostermarienberg in Burgenland

Burgenland

Burgenland is the easternmost and least populous state or Land of Austria. It consists of two Statutarstädte and seven districts with in total 171 municipalities. It is 166 km long from north to south but much narrower from west to east...

. On April 3, at the beginning of the Vienna Offensive

Vienna Offensive

The Vienna Offensive was launched by the Soviet 3rd Ukrainian Front in order to capture Vienna, Austria. The offensive lasted from 2–13 April 1945...

, Austrian politician Karl Renner

Karl Renner

Karl Renner was an Austrian politician. He was born in Untertannowitz in the Austro-Hungarian Empire and died in Vienna...

, then living in southern Lower Austria

Lower Austria

Lower Austria is the northeasternmost state of the nine states in Austria. The capital of Lower Austria since 1986 is Sankt Pölten, the most recently designated capital town in Austria. The capital of Lower Austria had formerly been Vienna, even though Vienna is not officially part of Lower Austria...

, established contact with the Soviets. Joseph Stalin

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin was the Premier of the Soviet Union from 6 May 1941 to 5 March 1953. He was among the Bolshevik revolutionaries who brought about the October Revolution and had held the position of first General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union's Central Committee...

had already assembled a future puppet government of Austrian communists in exile, but Tolbukhin's telegram changed Stalin's mind in favor of Renner.

On April 20, the Soviets, acting without asking their Western allies, instructed Renner to form the provisional government of Austria. Seven days later Renner's cabinet took office, declared the independence of Austria from Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

and called for the creation of a democratic state along the lines of the First Republic

Federal State of Austria

The Federal State of Austria refers to Austria from 1934 to 1938, according to its self-conception a non-party, in fact a single-party state led by the fascist Fatherland's Front...

. Soviet acceptance of Renner was not an isolated episode; their officers re-established district administrations and appointed local mayors, frequently following the advice of the locals, even before the battle was over.

Renner and his ministers were guarded and watched by NKVD

NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs was the public and secret police organization of the Soviet Union that directly executed the rule of power of the Soviets, including political repression, during the era of Joseph Stalin....

bodyguards. One-third of State Chancellor Renner's cabinet, including crucial seats of the Secretary of State for the Interior

Federal Ministry for the Interior (Austria)

The Federal Ministry for the Interior is a ministry of the Austrian federal government.It has offices in the Palais Modena. The current head of the ministry is minister Johanna Mikl-Leitner....

and the Secretary of State for Education

Education in Austria

The Republic of Austria has a free and public school system, and nine years of education are mandatory. Schools offer a series of vocational-technical and university preparatory tracks involving one to four additional years of education beyond the minimum mandatory level. The legal basis for...

, was staffed by Austrian Communists. The Western allies suspected the usual Soviet pattern of setting up puppet state

Puppet state

A puppet state is a nominal sovereign of a state who is de facto controlled by a foreign power. The term refers to a government controlled by the government of another country like a puppeteer controls the strings of a marionette...

s and did not recognize Renner. The British were particularly hostile; even Harry Truman

Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman was the 33rd President of the United States . As President Franklin D. Roosevelt's third vice president and the 34th Vice President of the United States , he succeeded to the presidency on April 12, 1945, when President Roosevelt died less than three months after beginning his...

, who personally believed that Renner was a trustworthy politician rather than a token front for the Kremlin, denied him recognition. But Renner had secured inter-party control by designating two Under-Secretaries of State in each of the ministries, being appointed by the two parties not placing the Secretary of State there.

As soon as Hitler's armies were pushed back into Germany, the Red Army

Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army started out as the Soviet Union's revolutionary communist combat groups during the Russian Civil War of 1918-1922. It grew into the national army of the Soviet Union. By the 1930s the Red Army was among the largest armies in history.The "Red Army" name refers to...

and the NKVD

NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs was the public and secret police organization of the Soviet Union that directly executed the rule of power of the Soviets, including political repression, during the era of Joseph Stalin....

began to comb the captured territories. By May 23 they reported arrests of 268 former Red Army men, 1208 Wehrmacht

Wehrmacht

The Wehrmacht – from , to defend and , the might/power) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the Heer , the Kriegsmarine and the Luftwaffe .-Origin and use of the term:...

men and 1,655 civilians. In the following weeks the British surrendered over forty thousand Cossacks who had fled to Western Austria to the Soviet authorities and certain death. In July and August, the Soviets brought in four regiments of NKVD troops

Internal Troops

The Internal Troops, full name Internal Troops of the Ministry for Internal Affairs ; alternatively translated as "Interior " is a paramilitary gendarmerie-like force in the now-defunct Soviet Union and its successor countries, particularly, in Russia, Ukraine, Georgia and Azerbaijan...

to "mop up" Vienna and seal the Czech border.

The Red Army had lost 17,000 lives in the Battle of Vienna and brought freedom from Nazism to the country. But the reputation of the Soviet soldiers was immediately ruined by the vast amount of sexual violence against women, which occurred in the first days and weeks after the Soviet victory. Repressions against civilians harmed Red Army reputation to such an extent that on September 28, 1945 Moscow issued an order forbidding violent interrogations. Red Army morale fell as soldiers prepared to be sent home; replacement of combat units with Ivan Konev

Ivan Konev

Ivan Stepanovich Konev , was a Soviet military commander, who led Red Army forces on the Eastern Front during World War II, retook much of Eastern Europe from occupation by the Axis Powers, and helped in the capture of Germany's capital, Berlin....

's permanent occupation force

Central Group of Forces

The Central Group of Forces was a Soviet military formation used to control Soviet troops in Central Europe on two occasions: in Austria and Hungary from 1945-55 and troops stationed in Czechoslovakia after the Prague Spring of 1968....

only marginally improved the Austrians' suffering. Throughout 1945 and 1946, all levels of Soviet command tried, in vain, to contain desertion and plunder by rank and file. According to Austrian police records for 1946, "men in Soviet uniform", usually drunk, accounted for more than 90% of registered crime (American soldiers: 5 to 7%). Yet, at the same time, the Soviet governors resisted expansion and arming of Austrian police force.

French, American and British troops

On July 9, 1945 the Allies agreed on the borders of their occupation zones in Austria. Vorarlberg

Vorarlberg

Vorarlberg is the westernmost federal-state of Austria. Although it is the second smallest in terms of area and population , it borders three countries: Germany , Switzerland and Liechtenstein...

and North Tyrol

North Tyrol

North Tyrol, or North Tirol is the main part of the Austrian state of Tyrol, located in the western part of the country. The other part of the state is East Tyrol, which also belongs to Austria, but does not share a border with North Tyrol....

were assigned to the French Zone; Salzburg

Salzburg (state)

Salzburg is a state or Land of Austria with an area of 7,156 km2, located adjacent to the German border. It is also known as Salzburgerland, to distinguish it from its capital city, also named Salzburg...

and Upper Austria

Upper Austria

Upper Austria is one of the nine states or Bundesländer of Austria. Its capital is Linz. Upper Austria borders on Germany and the Czech Republic, as well as on the other Austrian states of Lower Austria, Styria, and Salzburg...

south of the Danube to the American Zone; East Tyrol

East Tyrol

East Tyrol, or East Tirol , is an exclave of the Austrian state of Tyrol, sharing no border with the main North Tyrol part of the state. It corresponds with the administrative district of Lienz....

, Carinthia

Carinthia (state)

Carinthia is the southernmost Austrian state or Land. Situated within the Eastern Alps it is chiefly noted for its mountains and lakes.The main language is German. Its regional dialects belong to the Southern Austro-Bavarian group...

and Styria to the British Zone; and Burgenland

Burgenland

Burgenland is the easternmost and least populous state or Land of Austria. It consists of two Statutarstädte and seven districts with in total 171 municipalities. It is 166 km long from north to south but much narrower from west to east...

, Lower Austria

Lower Austria

Lower Austria is the northeasternmost state of the nine states in Austria. The capital of Lower Austria since 1986 is Sankt Pölten, the most recently designated capital town in Austria. The capital of Lower Austria had formerly been Vienna, even though Vienna is not officially part of Lower Austria...

, and the Mühlviertel

Mühlviertel

The Mühlviertel is an Austrian region belonging to the state of Upper Austria: it is one of four "quarters" of Upper Austria, the others being Hausruckviertel, Traunviertel, and Innviertel. It is named for the two rivers and .-Region:...

area of Upper Austria, north of the Danube, to the Soviet Zone. The occupation zones were assigned so that the French and American zones bordered those countries' respective zones in Germany and the Soviet zone bordered future Warsaw Pact

Warsaw Pact

The Warsaw Treaty Organization of Friendship, Cooperation, and Mutual Assistance , or more commonly referred to as the Warsaw Pact, was a mutual defense treaty subscribed to by eight communist states in Eastern Europe...

states. Vienna

Vienna

Vienna is the capital and largest city of the Republic of Austria and one of the nine states of Austria. Vienna is Austria's primary city, with a population of about 1.723 million , and is by far the largest city in Austria, as well as its cultural, economic, and political centre...

was divided among all four Allies. The historical center of Vienna

Innere Stadt

The Innere Stadt is the 1st municipal District of Vienna . The Innere Stadt is the old town of Vienna. Until the city boundaries were expanded in 1850, the Innere Stadt was congruent with the city of Vienna...

was declared an international zone, in which occupation forces changed every month. Movement of occupation troops ("zone swap") continued until the end of July.

The first Americans arrived in Vienna in the end of July 1945, when the Soviets were pressing Renner to surrender Austrian oil field

Oil field

An oil field is a region with an abundance of oil wells extracting petroleum from below ground. Because the oil reservoirs typically extend over a large area, possibly several hundred kilometres across, full exploitation entails multiple wells scattered across the area...

s. Americans objected and blocked the deal but ultimately the Soviets assumed control over Austrian oil in their zone. The British arrived only in September. The Allied Council of four military governors convened for its first meeting in Vienna on September 12, 1945. It refused to recognize Renner's claims for a national government but did not prevent him from extending influence into the Western zones. Renner appointed vocal anti-communist Karl Gruber

Karl Gruber

Karl Gruber was an Austrian politician and diplomat. During World War II, he was working for a German firm in Berlin. After the war, in 1945 he became Landeshauptmann of Tyrol for a short time...

to represent Austria as its Foreign Minister and tried to reduce Communist influence. On October 20, 1945, Renner's reformed cabinet was recognized by the Western allies and received a go-ahead for the first legislative election.

The first general elections after the war

The vote held on November 25, 1945Austrian legislative election, 1945

The elections to the Austrian National Council held in fall of 1945 were the first after World War II. The elections were held according to the Austrian election law of 1929, with all citizens at least 21 years old eligible to vote, however former Nazis were banned from voting, official sources...

was a blow for the Communist Party of Austria

Communist Party of Austria

The Communist Party of Austria is a communist party based in Austria. Established in 1918, it was banned between 1933 and 1945 under both the Austrofascist regime, and German control of Austria during World War II...

which received less than 5% of the vote. The coalition of Christian Democrats

Christian Democracy

Christian democracy is a political ideology that seeks to apply Christian principles to public policy. It emerged in nineteenth-century Europe under the influence of conservatism and Catholic social teaching...

(ÖVP

Austrian People's Party

The Austrian People's Party is a Christian democratic and conservative political party in Austria. A successor to the Christian Social Party of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, it is similar to the Christian Democratic Union of Germany in terms of ideology...

) and Social Democrats

Social democracy

Social democracy is a political ideology of the center-left on the political spectrum. Social democracy is officially a form of evolutionary reformist socialism. It supports class collaboration as the course to achieve socialism...

(SPÖ

Social Democratic Party of Austria

The Social Democratic Party of Austria is one of the oldest political parties in Austria. The SPÖ is one of the two major parties in Austria, and has ties to trade unions and the Austrian Chamber of Labour. The SPÖ is among the few mainstream European social-democratic parties that have preserved...

), backed by 90% of the votes, assumed control over the cabinet and offered the seat of Federal Chancellor

Chancellor of Austria

The Federal Chancellor is the head of government in Austria. Its deputy is the Vice-Chancellor. Before 1918, the equivalent office was the Minister-President of Austria. The Federal Chancellor is considered to be the most powerful political position in Austrian politics.-Appointment:The...

to Christian Democrat Julius Raab

Julius Raab

Julius Raab was a Conservative Austrian politician. He was Federal Chancellor of Austria from 1953 to 1961. Raab steered Allied-occupied Austria to independence. In 1955 he negotiated and signed the Austrian State Treaty...

. The Soviets veto

Veto

A veto, Latin for "I forbid", is the power of an officer of the state to unilaterally stop an official action, especially enactment of a piece of legislation...

ed Raab, due to his political role in the 1930s. Instead President Karl Renner, with the consent of parliament, appointed Leopold Figl

Leopold Figl

Leopold Figl was an Austrian politician of the Austrian People's Party and the first Federal Chancellor after World War II...

who was just barely acceptable to the Soviets. They responded with massive and coordinated expropriation of Austrian economic potential.

The Potsdam Agreement

Potsdam Agreement

The Potsdam Agreement was the Allied plan of tripartite military occupation and reconstruction of Germany—referring to the German Reich with its pre-war 1937 borders including the former eastern territories—and the entire European Theatre of War territory...

allowed confiscation of "German external assets" in Austria, and the Soviets used the vagueness of this definition to the full. In less than a year they dismantled and shipped to the East industrial equipment valued at around 500 million U.S. dollars. American High Commissioner Mark W. Clark vocally resisted Soviet expansionist intentions, and his reports to Washington, along with George F. Kennan

George F. Kennan

George Frost Kennan was an American adviser, diplomat, political scientist and historian, best known as "the father of containment" and as a key figure in the emergence of the Cold War...

's The Long Telegram

X Article

The X Article, formally titled The Sources of Soviet Conduct, was published in Foreign Affairs magazine in July 1947. The article was written by George F. Kennan, the Deputy Chief of Mission of the United States to the USSR, from 1944 to 1946, under ambassador W. Averell Harriman.-Background:G. F....

, supported Truman's tough stance against the Soviets. Thus, according to Bischof, the Cold War

Cold War

The Cold War was the continuing state from roughly 1946 to 1991 of political conflict, military tension, proxy wars, and economic competition between the Communist World—primarily the Soviet Union and its satellite states and allies—and the powers of the Western world, primarily the United States...

in Austria began in the spring of 1946, one year before the outbreak of the global Cold War.

On June 28, 1946, the Allies signed the Second Control Agreement that loosened their dominance over the Austrian government. Parliament of Austria

Parliament of Austria

In the Parliament of Austria is vested the legislative power of the Republic of Austria. The institution consists of two chambers,* the National Council and* the Federal Council ....

was de facto

De facto

De facto is a Latin expression that means "concerning fact." In law, it often means "in practice but not necessarily ordained by law" or "in practice or actuality, but not officially established." It is commonly used in contrast to de jure when referring to matters of law, governance, or...

relieved of Allied control. From now on its decision could be overturned only by unanimous vote by all four Allies. The Soviet veto

Veto

A veto, Latin for "I forbid", is the power of an officer of the state to unilaterally stop an official action, especially enactment of a piece of legislation...

es against Austrian laws were routinely voided by the Western opposition. For the next nine years the country was gradually emancipated from foreign control, and evolved from a "nation under tutelage

Tutor

A tutor is a person employed in the education of others, either individually or in groups. To tutor is to perform the functions of a tutor.-Teaching assistance:...

" to full independence. The government of Austria possessed its own independent vision of the future, reacting to adverse circumstances and at times turning them to their own benefit. First allied talks on Austrian independence were held in January 1947, and deadlocked over the issue of "German assets" in Soviet possession.

Mounting losses

In late 1945 and early 1946 Allied occupation force in Austria peaked at around 150,000 Soviet, 55,000 British, 40,000 American and 15,000 French troops. The costs of keeping these troops were levied on the Austrian government. At first, Austria had to pay the whole occupation bill; in 1946 occupation costs were capped at 35% of Austrian state expenditures, equally split between the Soviets and the Western allies.Coincidentally with the Second Control Agreement, the Soviets changed their economic policy from outright plunder to running expropriated Austrian businesses for a profit. Austrian communists advised Stalin to nationalize the whole economy, but he deemed the proposal to be too radical. Between February and June 1946, the Soviets expropriated hundreds of businesses left in their zone. On June 27, 1946, they amalgamated these assets into the USIA

Administration for Soviet Property in Austria

The Administration for Soviet Property in Austria, or the USIA was formed in the Soviet zone of Allied-occupied Austria in June 1946 and operated until the withdrawal of Soviet troops in 1955. USIA operated as a de-facto state corporation and controlled over four hundred expropriated Austrian...

, a conglomerate

Conglomerate (company)

A conglomerate is a combination of two or more corporations engaged in entirely different businesses that fall under one corporate structure , usually involving a parent company and several subsidiaries. Often, a conglomerate is a multi-industry company...

of over 400 enterprises. It controlled not more than 5% of Austrian economic output but possessed substantial, or even monopolistic, share in glass, steel, oil and transportation industries. The USIA was weakly integrated with the rest of Austrian economy: its products were primarily shipped to the East, its profits de-facto confiscated and its taxes left unpaid by the Soviets. The Austrian government refused to recognize USIA legal title over its possessions; in retaliation, the USIA refused to pay Austrian taxes and tariffs. This competitive advantage helped to keep USIA enterprises afloat despite their mounting obsolescence. The Soviets had no intention to reinvest their profits, and USIA assets gradually decayed and lost their competitive edge. The Austrian government feared paramilitary communist gangs sheltered by the USIA and scorned it for being "an economy of exploitation in colonial style." The economy of the Soviet zone eventually reunited with the rest of the country.

South Tyrol

South Tyrol

South Tyrol , also known by its Italian name Alto Adige, is an autonomous province in northern Italy. It is one of the two autonomous provinces that make up the autonomous region of Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol. The province has an area of and a total population of more than 500,000 inhabitants...

, a disputed territory in the Alps

Alps

The Alps is one of the great mountain range systems of Europe, stretching from Austria and Slovenia in the east through Italy, Switzerland, Liechtenstein and Germany to France in the west....

, was returned to Italy. The "thirty-second decision" of the Council of Foreign Ministers

Council of Foreign Ministers

Council of Foreign Ministers was an organisation agreed upon at the Potsdam Conference in 1945 and announced in the Potsdam Agreement.The Potsdam Agreement specified that the Council would be composed of the Foreign Ministers of the United Kingdom, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, China,...

to grant South Tyrol to Italy (September 4, 1945) disregarded popular opinion in Austria and the possible effects of a forced repatriation

Expulsion of Germans after World War II

The later stages of World War II, and the period after the end of that war, saw the forced migration of millions of German nationals and ethnic Germans from various European states and territories, mostly into the areas which would become post-war Germany and post-war Austria...

of 200,000 German-speaking Tyroleans. The decision was motivated largely by the British desire to reward Italy

Italy

Italy , officially the Italian Republic languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Italy's official name is as follows:;;;;;;;;), is a unitary parliamentary republic in South-Central Europe. To the north it borders France, Switzerland, Austria and...

, a country far more important for the containment

Containment

Containment was a United States policy using military, economic, and diplomatic strategies to stall the spread of communism, enhance America’s security and influence abroad, and prevent a "domino effect". A component of the Cold War, this policy was a response to a series of moves by the Soviet...

of world communism. Renner's objections came in too late and carried too little weight to have effect. Popular and official protests continued through 1946. The signatures of 150,000 South Tyroleans did not alter the decision. South Tyrol is today an Italian autonomous province (Bolzano/Bozen

South Tyrol

South Tyrol , also known by its Italian name Alto Adige, is an autonomous province in northern Italy. It is one of the two autonomous provinces that make up the autonomous region of Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol. The province has an area of and a total population of more than 500,000 inhabitants...

) with a German-speaking majority.

Hunger

In 1947, the Austrian economy, including USIA enterprises, reached 61% of pre-war level, but it was disproportionately weak in consumer goods production (42% of pre-war level). Food remained the worst problem. The country, according to American reports, survived 1945 and 1946 on "a near-starvation diet" with daily rationsRationing

Rationing is the controlled distribution of scarce resources, goods, or services. Rationing controls the size of the ration, one's allotted portion of the resources being distributed on a particular day or at a particular time.- In economics :...

remaining below 2000 calories until the end of 1947. 65% of Austrian agricultural output and nearly all oil concentrated in the Soviet zone, complicating the Western Allies' task of feeding the population in their own zones.

From March 1946 to June 1947, 64% of these rations were provided by the UNRRA

United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration

The United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration was an international relief agency, largely dominated by the United States but representing 44 nations. Founded in 1943, it became part of the United Nations in 1945, was especially active in 1945 and 1946, and largely shut down...

. Heating depended on supplies of German coal shipped by the U.S. on lax credit terms. Draught of 1946 further depressed farm output and hydroelectric power generation. Figl's government, the Chambers of Labor, Trade and Agriculture, and the Austrian Trade Union Federation

Austrian Trade Union Federation

-External links:*...

(ÖGB) temporarily resolved the crisis in favor of tight regulation of food and labor markets. Wage increases were limited and locked to commodity prices through annual price-wage agreements. The negotiations set a model of building consensus

Consensus decision-making

Consensus decision-making is a group decision making process that seeks the consent, not necessarily the agreement, of participants and the resolution of objections. Consensus is defined by Merriam-Webster as, first, general agreement, and second, group solidarity of belief or sentiment. It has its...

between elected and non-elected political elites that became the basis of post-war Austrian democracy, known as Austrian Social Partnership and Austro-corporatism

Corporatism

Corporatism, also known as corporativism, is a system of economic, political, or social organization that involves association of the people of society into corporate groups, such as agricultural, business, ethnic, labor, military, patronage, or scientific affiliations, on the basis of common...

.

The severe winter of 1946–1947 was followed by the disastrous summer of 1947, when potato

Potato

The potato is a starchy, tuberous crop from the perennial Solanum tuberosum of the Solanaceae family . The word potato may refer to the plant itself as well as the edible tuber. In the region of the Andes, there are some other closely related cultivated potato species...

harvest barely made 30% of pre-war output. Food shortages of 1947 were aggravated by the withdrawal of UNRRA aid, the spiraling inflation and the demoralizing failure of State Treaty talks. In April 1947, the government was unable to distribute any rations at all, and on May 5 Vienna was shaken by a violent food riot. Unlike earlier popular protests, this time the demonstrators, led by the Communists, called to curb the westernization of Austrian politics. In August, food riot in Bad Ischl

Bad Ischl

Bad Ischl is a spa town in Austria. It lies in the southern part of Upper Austria, at the Traun River in the centre of the Salzkammergut region. The town consists of the Katastralgemeinden Ahorn, Bad Ischl, Haiden, Jainzen, Kaltenbach, Lauffen, Lindau, Pfandl, Perneck, Reiterndorf and Rettenbach...

turned into a pogrom

Pogrom

A pogrom is a form of violent riot, a mob attack directed against a minority group, and characterized by killings and destruction of their homes and properties, businesses, and religious centres...

of local Jews. In November, food shortage sparked workers' strikes in British-occupied Styria. Figl's government declared that the food riots were a failed communist putsch

Coup d'état

A coup d'état state, literally: strike/blow of state)—also known as a coup, putsch, and overthrow—is the sudden, extrajudicial deposition of a government, usually by a small group of the existing state establishment—typically the military—to replace the deposed government with another body; either...

, although later historians refuted this statement as an exaggeration.

In June 1947, the month when the UNRRA stopped shipments of food to Austria, the extent of the food crisis compelled the U.S. government to issue 300 million dollars in food aid. In the same month Austria was invited to discuss its participation in the Marshall Plan

Marshall Plan

The Marshall Plan was the large-scale American program to aid Europe where the United States gave monetary support to help rebuild European economies after the end of World War II in order to combat the spread of Soviet communism. The plan was in operation for four years beginning in April 1948...

. Direct aid and subsidies helped Austria to survive the hunger of 1947. On the other hand, they depressed food prices and thus discouraged local farmers, delaying the rebirth of Austrian agriculture.

Marshall Plan

Austria finalized its Marshall Plan program in the end of 1947 and received the first trancheTranche

In structured finance, a tranche is one of a number of related securities offered as part of the same transaction. The word tranche is French for slice, section, series, or portion, and is cognate to English trench . In the financial sense of the word, each bond is a different slice of the deal's...

of Marshall Plan aid in March 1948. Austrian heavy industry (or what was left of it) concentrated around Linz

Linz

Linz is the third-largest city of Austria and capital of the state of Upper Austria . It is located in the north centre of Austria, approximately south of the Czech border, on both sides of the river Danube. The population of the city is , and that of the Greater Linz conurbation is about...

, in the American zone, and in British-occupied Styria. Their products were in high demand in post-war Europe. Quite naturally, the administrators of the Marshall Plan channeled available financial aid into heavy industry controlled by the American and British forces. American military and political leaders made no secret of their intentions: Geoffrey Keyes

Geoffrey Keyes

-External links:...

said that "we cannot afford to let this key area (Austria) fall under exclusive influence of the Soviet Union." Marshall Plan was deployed primarily against the Soviet zone but it was not completely excluded: it received 8% of Marshall plan investments (compared to 25% of food and other physical commodities). Austrian government regarded financial aid to the Soviet zone as a lifeline holding the country together. This was the only case when Marshall Plan funds were distributed in Soviet-occupied territories.

The Marshall Plan was not universally popular, especially in its initial phase. It benefited some trades such as metallurgy but depressed others such as agriculture. Heavy industries quickly recovered, from 74.7% of pre-war output in 1948 to 150.7% in 1951. American planners deliberately neglected consumer goods industries, construction trades and small business. Their workers, almost half of Austrian industrial workforce, suffered from rising unemployment. In 1948–1949, a substantial share of Marshall Plan funds allocated to Austria was used to subsidize imports of food. American money, effectively, raised real wage

Real wage

The term real wages refers to wages that have been adjusted for inflation. This term is used in contrast to nominal wages or unadjusted wages. Real wages provide a clearer representation of an individual's wages....

s of Austrian workers: grain price in Austria was at about one-third of the world price, while local agriculture remained in ruin. Marshall Plan aid gradually removed many of the causes of popular unrest that shook the country in 1947, but Austria remained dependent on food imports.

The second stage of the Marshall Plan, which began in 1950, concentrated on productivity

Productivity

Productivity is a measure of the efficiency of production. Productivity is a ratio of what is produced to what is required to produce it. Usually this ratio is in the form of an average, expressing the total output divided by the total input...

of the economy. According to Michael J. Hogan

Michael Hogan (academic)

Michael J. Hogan is an American academic who has served in the administrations or on the faculty of many American universities, wrote or edited numerous books, contributed as an adviser to the U. S. Department of State and several documentaries....

, "in the most profound sense, it involved the transfer of attitudes, habits and values as well, indeed a whole way of life that Marshall planners associated with progress in the marketplace of politics and social relationships as much as they did with industry and agriculture." The program, as instructed by American lawmakers, targeted improvement in factory-level productivity, labor-management relations, free trade unions and introduction of modern business practices. The Economic Cooperation Administration

Economic Cooperation Administration

The Economic Cooperation Administration was a United States government agency set up in 1948 to administer the Marshall Plan. It reported to both the State Department and the Department of Commerce. The agency's head was Paul G. Hoffman, a former head of Studebaker. Much of the rest of the...

, which operated until December 1951, distributed around 300 million dollars in technical assistance and attempted steering the Austrian social partnership (political parties, labor unions, business associations and executive government) in favor of productivity and growth instead of redistribution and consumption.

Their efforts were thwarted by the Austrian practice of making decisions behind closed doors. The Americans struggled to change it in favor of open, public discussion. They took a strong anti-cartel

Cartel

A cartel is a formal agreement among competing firms. It is a formal organization of producers and manufacturers that agree to fix prices, marketing, and production. Cartels usually occur in an oligopolistic industry, where there is a small number of sellers and usually involve homogeneous products...

stance, appreciated by the Socialists, and pressed the Austrian government to remove anti-competition legislation. But ultimately they were responsible for the creation of the vast monopolistic public sector of Austrian economy (and thus politically benefiting the Socialists).

According to Bischof, "no European nation benefited more from Marshall Plan than Austria." Austria received nearly a billion U.S. dollars through Marshall Plan, and half a billion in humanitarian aid. The Americans also refunded to Austria all occupation costs charged in 1945–1946, around 300 million. In 1948-1949 Marshall Plan aid contributed 14% of Austrian national income, the highest ratio of all involved countries. Per capita, aid amounted to 132 dollars compared to 19 dollars for the Germans. But Austria also paid more war reparations

War reparations

War reparations are payments intended to cover damage or injury during a war. Generally, the term war reparations refers to money or goods changing hands, rather than such property transfers as the annexation of land.- History :...

per capita than any other Axis state

Axis Powers

The Axis powers , also known as the Axis alliance, Axis nations, Axis countries, or just the Axis, was an alignment of great powers during the mid-20th century that fought World War II against the Allies. It began in 1936 with treaties of friendship between Germany and Italy and between Germany and...

or territory. Total war reparations taken by the Soviet Union including withdrawn USIA profits, looted property and the final settlement agreed in 1955, are estimated between 1.54 and 2.65 billion U.S. dollars (Eisterer: 2 to 2.5 billion).

Cold War

The British had been quietly arming Austrian gendarmes since 1945 and discussed creation of a proper military with Austrians in 1947. The Americans meanwhile feared that Vienna could be the scene of another Berlin BlockadeBerlin Blockade

The Berlin Blockade was one of the first major international crises of the Cold War and the first resulting in casualties. During the multinational occupation of post-World War II Germany, the Soviet Union blocked the Western Allies' railway and road access to the sectors of Berlin under Allied...

. They set up and filled emergency food dumps, and prepared to airlift

Airlift

Airlift is the act of transporting people or cargo from point to point using aircraft.Airlift may also refer to:*Airlift , a suction device for moving sand and silt underwater-See also:...

supplies to Vienna while the Austrian government created a backup base in Salzburg

Salzburg

-Population development:In 1935, the population significantly increased when Salzburg absorbed adjacent municipalities. After World War II, numerous refugees found a new home in the city. New residential space was created for American soldiers of the postwar Occupation, and could be used for...

. The American command secretly trained the soldiers of underground Austrian military at a rate of two hundred men a week. The Gendarmerie

Gendarmerie

A gendarmerie or gendarmery is a military force charged with police duties among civilian populations. Members of such a force are typically called "gendarmes". The Shorter Oxford English Dictionary describes a gendarme as "a soldier who is employed on police duties" and a "gendarmery, -erie" as...

knowingly hired Wehrmacht

Wehrmacht

The Wehrmacht – from , to defend and , the might/power) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the Heer , the Kriegsmarine and the Luftwaffe .-Origin and use of the term:...

veterans and VdU

Federation of Independents

The Federation of Independents was a German national and national-liberal political party in Austria active from 1949 to 1955...

members; the denazification

Denazification

Denazification was an Allied initiative to rid German and Austrian society, culture, press, economy, judiciary, and politics of any remnants of the National Socialist ideology. It was carried out specifically by removing those involved from positions of influence and by disbanding or rendering...

of Austria's 537,000 registered Nazis had largely ended in 1948.

Austrian communists appealed to Stalin to partition their country along the German model, but in February 1948 Andrei Zhdanov

Andrei Zhdanov

Andrei Alexandrovich Zhdanov was a Soviet politician.-Life:Zhdanov enlisted with the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party in 1915 and was promoted through the party ranks, becoming the All-Union Communist Party manager in Leningrad after the assassination of Sergei Kirov in 1934...

vetoed the idea: Austria had more value as a bargaining chip than as another unstable client state. The continuing talks on Austrian independence stalled in 1948 but progressed to a "near breakthrough" in 1949: the Soviets lifted most of their objections, and the Americans suspected foul play. The Pentagon

The Pentagon

The Pentagon is the headquarters of the United States Department of Defense, located in Arlington County, Virginia. As a symbol of the U.S. military, "the Pentagon" is often used metonymically to refer to the Department of Defense rather than the building itself.Designed by the American architect...

was convinced that the withdrawal of Western troops would leave the country open to Soviet invasion of the Czech model

Czechoslovak coup d'état of 1948

The Czechoslovak coup d'état of 1948 – in Communist historiography known as "Victorious February" – was an event late that February in which the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, with Soviet backing, assumed undisputed control over the government of Czechoslovakia, ushering in over four decades...

. Clark insisted that before their departure the United States must secretly train and arm the core of a future Austrian military. Serious secret training of the Austrian forces (the B-Gendarmerie) began in 1950 but soon stalled due to US defense budget cuts in 1951. Austrian gendarmes were trained primarily as an anti-coup police force, but they also studied Soviet combat practice and counted on cooperation with the Yugoslavs

Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia refers to three political entities that existed successively on the western part of the Balkans during most of the 20th century....

in case of an open Soviet invasion.

Although in the fall of 1950 the Western powers replaced their military representatives with civilian diplomats, strategic situation became gloomier than ever. The Korean War

Korean War

The Korean War was a conventional war between South Korea, supported by the United Nations, and North Korea, supported by the People's Republic of China , with military material aid from the Soviet Union...

experience persuaded Washington that Austria may become "Europe's Korea" and sped up rearmament of the "secret ally". International tension was coincident with a severe internal economic and social crisis. The planned withdrawal of American food subsidies spelled a sharp drop in real wage

Real wage

The term real wages refers to wages that have been adjusted for inflation. This term is used in contrast to nominal wages or unadjusted wages. Real wages provide a clearer representation of an individual's wages....

s for all Austrians. The government and the unions deadlocked in negotiations, and gave the Austrian communists the opportunity to organize the 1950 Austrian general strikes

1950 Austrian general strikes

The Austrian General Strikes of 1950 were masterminded by the Communist Party of Austria with half-hearted support of the Soviet occupation authorities. In August–October of 1950 Austria faced a severe social and economic crisis caused by anticipated withdrawal of American financial aid and a sharp...

which became the gravest threat to Austria since the 1947 food riots. The communists stormed and took over ÖGB

Austrian Trade Union Federation

-External links:*...

offices, disrupted railroad traffic but failed to recruit sufficient public support and had to admit defeat. The Soviets and the Western allies did not dare to actively intervene in the strikes. The strike intensified militarization of Western Austria, this time with active input from France

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

and the CIA

Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency is a civilian intelligence agency of the United States government. It is an executive agency and reports directly to the Director of National Intelligence, responsible for providing national security intelligence assessment to senior United States policymakers...

. Despite the strain of Korean War, by the end of 1952 the American "Stockpile A" (A for Austria) in France and Germany amassed 227 thousand tons of materiel

Materiel

Materiel is a term used in English to refer to the equipment and supplies in military and commercial supply chain management....

earmarked for Austrian armed forces.

Detente

The end of the Korean War and the death of Joseph StalinJoseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin was the Premier of the Soviet Union from 6 May 1941 to 5 March 1953. He was among the Bolshevik revolutionaries who brought about the October Revolution and had held the position of first General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union's Central Committee...

defused the standoff in Austria, and the country was rapidly, but not completely, demilitarized. After the Soviet Union had relieved Austria of the need to pay for the cost of their reduced army of 40,000 men, the British and French followed suit and reduced their forces to a token presence. Finally, the Soviets replaced their military governor with a civilian ambassador

Ivan Ilyichev

Ivan Ivanovich Ilyichev , , was a Soviet military official, and in later life a diplomat....

. The former border between Eastern and Western Austria became a mere demarcation line

Demarcation line

A demarcation line means simply a boundary around a specific area, but is commonly used to denote a temporary geopolitical border, often agreed upon as part of an armistice or ceasefire.See the following examples:...

.

Chancellor Julius Raab

Julius Raab

Julius Raab was a Conservative Austrian politician. He was Federal Chancellor of Austria from 1953 to 1961. Raab steered Allied-occupied Austria to independence. In 1955 he negotiated and signed the Austrian State Treaty...

, elected in April 1953, removed pro-Western foreign minister Gruber and steered Austria to a more neutral policy. Raab carefully probed the Soviets about resuming the talks on Austrian independence, but until February 1955 it remained contingent on a solution to the larger German problem. The Western strategy of rearming West Germany, formulated in the Paris Agreement

London and Paris Conferences

The London and Paris Conferences were two related conferences in London and Paris in late September and October 1954 to determine the status of West Germany...

, was unacceptable to the Soviets. They responded with a counter-proposal for a pan-European security system that, they said, could speed up reunification of Germany, and again the West suspected foul play. Eisenhower

Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower was the 34th President of the United States, from 1953 until 1961. He was a five-star general in the United States Army...

, in particular, had "an utter lack of confidence in the reliability and integrity of the men in the Kremlin... the Kremlin is pre-empting the right to speak for the small nations of the world"

In January 1955, Soviet diplomats Andrey Gromyko, Vladimir Semenov and Georgy Pushkin secretly advised Vyacheslav Molotov

Vyacheslav Molotov

Vyacheslav Mikhailovich Molotov was a Soviet politician and diplomat, an Old Bolshevik and a leading figure in the Soviet government from the 1920s, when he rose to power as a protégé of Joseph Stalin, to 1957, when he was dismissed from the Presidium of the Central Committee by Nikita Khrushchev...

to unlink Austrian and German issues, expecting that the new talks on Austria would delay ratification of the Paris Agreement. Molotov publicly announced the new Soviet initiative on 8 February. He put forward three conditions for Austrian independence: neutrality, no foreign military bases and guarantees against a new Anschluss

Anschluss

The Anschluss , also known as the ', was the occupation and annexation of Austria into Nazi Germany in 1938....

.

Independence

In March, Molotov clarified his plan through a series of consultations with ambassador Norbert Bischoff: Austria was no longer a hostage of the German issue. Molotov invited Raab to Moscow for bilateral negotiations that, if successful, had to be followed by a Four Powers conference. By this time Paris Agreements were ratified by France and Germany, yet again the British and Americans suspected a trap of the same sort that HitlerAdolf Hitler