Scottish New Zealander

Encyclopedia

Scottish New Zealanders are New Zealanders

who are of Scottish

ancestry.

Scottish

migration to New Zealand

dates back to the earliest period of European colonisation, with a large proportion of Pākehā

New Zealanders being of Scottish descent. However, identification as "British" or "European" New Zealanders can sometimes obscure their origin. Many Scottish New Zealanders have Māori or other non-European ancestry.

However, these figures only include people born in Scotland, not those New Zealanders who claim a Scottish identity through their parents, grandparents, or even further back. In addition, many New Zealanders come from mixed origins, with Scottish New Zealanders co-identifying as Māori or another ethnic group.

In 2006, 15,039 self-identified as Scottish.

The Te Ara Encyclopedia notes that in many cases, the distinctive features of Scottish settlers were often wiped out in a generation or two, and replaced with a British identity which consisted mostly of English culture:

The Te Ara Encyclopedia notes that in many cases, the distinctive features of Scottish settlers were often wiped out in a generation or two, and replaced with a British identity which consisted mostly of English culture:

Today, if there can be said to be a "stronghold" of Scottish culture in New Zealand, it would be in the provinces of Southland

and Otago

.

Some of the following aspects of Scottish culture can still be found in some parts of New Zealand.

The Scottish Gaelic language

and culture did not fare well. Turakina

in Wanganui

was originally settled by Gaelic speakers, but there is not much trace other than annual Highland games.

In the past, Scottish army regiments have been raised from New Zealand, and their successor units still exist in the New Zealand Army

. According to Collins Encyclopaedia of Scotland

:

The Otago and Southland Regiment

is still linked to the Highlanders in the British Army.

, materialised in March 1848 with the arrival of the first two immigrant ships from Greenock

on the Firth of Clyde

-- the John Wickliffe

and the Philip Laing. Captain William Cargill

, a veteran of the Peninsular War

, served as the colony's first leader: Otago citizens subsequently elected him to the office of Superintendent.

Provincial government in New Zealand ceased in 1876, and the national limelight gradually shifted northwards. The colony divided itself into counties in 1876, two in Otago being named after the Scottish independence heroes Wallace

and Bruce

.

Originally part of Otago Province

, Southland Province (a small part of the present Region, centred on Invercargill

) was one of the provinces of New Zealand

from 1861 until 1870. It rejoined Otago Province due to financial difficulties, and the provinces were abolished entirely in 1876.

In 1856, a petition was put forward to Thomas Gore Browne

, the Governor of New Zealand

, for a port at Bluff. Browne agreed to the petition and gave the name Invercargill

to the settlement north of the port. Inver comes from the Scots Gaelic word inbhir meaning a river's mouth and Cargill is in honour of Captain William Cargill

, who was at the time the Superintendent of Otago

, of which Southland was then a part.

The Lay Association of the Free Church of Scotland

The Lay Association of the Free Church of Scotland

founded Dunedin at the head of Otago Harbour in 1848 as the principal town of its Scottish

settlement. The name comes from Dùn Èideann, the Scottish Gaelic name for Edinburgh

, the Scottish capital. Charles Kettle

the city's surveyor, instructed to emulate the characteristics of Edinburgh, produced a striking, 'Romantic' design. The result was both grand and quirky streets as the builders struggled and sometimes failed to construct his bold vision across the challenging landscape. Captain William Cargill

, a veteran of the war against Napoleon, was the secular leader. The Reverend Thomas Burns

, a nephew of the poet Robert Burns

, was the spiritual guide.

The Octagon

was first laid out during Charles Kettle

's surveying of the city in 1846. His plans for the centre of Dunedin included a large Octagonal area (Moray Place

) enclosing a smaller octagonal shape, originally designated as a reserve. Despite the reserve status, the Church of England

sought to build in the centre of the Octagon, applying directly to Governor

Sir George Grey

. It was not until building was about to commence that the local (predominantly Scottish and Presbyterian) community became aware of what was happening. This resulted in a major furore within the city. Otago Superintendent William Cargill

was put in charge of the dispute, resulting in the Anglicans being forced to withdraw their plans for The Octagon (The Anglican St. Paul's Cathedral

stands today at the northern edge of The Octagon).

Many of the suburbs of Dunedin are named after their Edinburgh equivalents

Dunedin's main rugby team are called The Highlanders. The name Highlanders was chosen after the early Scottish

Dunedin's main rugby team are called The Highlanders. The name Highlanders was chosen after the early Scottish

settlers in the lower South Island

. These Scottish settlers were the founders of Dunedin

—known as the "Edinburgh

of the South", and the city where the Highlanders are based. According to the Highlanders official website: " The name and image of the Highlander conjures up visions of fierce independence, pride in one's roots, loyalty, strength, kinship, honesty, and hard work." The colours of the Highlanders encompasses the provincial colours of North Otago, Otago, and Southland; yellow, blue and maroon

. Blue is also the predominant colour of the Flag of Scotland

, and is used by many sports teams in that country.

Dunedin founders Thomas Burns and James Macandrew

Dunedin founders Thomas Burns and James Macandrew

urged the Otago Provincial Council during the 1860s to set aside a land endowment for an institute of higher education. An ordinance of the council established the university in 1869, giving it 100000 acres (404.7 km²) of land, and the power to grant degrees in Arts, Medicine, Law and Music. Burns was named Chancellor, but he did not live to see the university open on 5 July 1871. The university issued just one degree before becoming an affiliate college of the federal University of New Zealand

in 1874. With the dissolving of the University of New Zealand in 1961 and passage of the University of Otago Amendment Act 1961, the university regained authority to confer degrees.

The University's coat of arms was granted by the Lord Lyon King of Arms on 21 January 1948, and features a yellow saltire, on blue.

. They have had a mixed reception, but have included some notable players. The original "kilted Kiwi" was Sean Lineen

. In order to qualify, they either have to have at least one Scottish parent or grandparent.

Other so-called "kilted Kiwis" apart from Sean Lineen have included:

However, this has not always been a one way trade. At least one All Black was born in Scotland - Angus Stuart

.

There are Scottish placenames all over New Zealand, but they tend to be concentrated in the southern part of South Island

There are Scottish placenames all over New Zealand, but they tend to be concentrated in the southern part of South Island

. Notable Scottish placenames in New Zealand include:

The South Island also contains the Strath-Taieri and the Ben Ohau Range

of mountains, both combining Scots Gaelic and Maori

origins. Invercargill

has the appearance of a Scottish name, since it combines the Scottish prefix "Inver" (Inbhir), meaning a river's mouth, with "Cargill", the name of a Scottish official. (Many of Invercargill's main streets are named after Scottish rivers: Dee, Tay, Spey, Esk, Don, Doon, Clyde, etc.). Inchbonnie

is a hybrid of Lowland Scots

and Scottish Gaelic

New Zealanders

New Zealanders, colloquially known as Kiwis, are citizens of New Zealand. New Zealand is a multiethnic society, and home to people of many different national origins...

who are of Scottish

Scottish people

The Scottish people , or Scots, are a nation and ethnic group native to Scotland. Historically they emerged from an amalgamation of the Picts and Gaels, incorporating neighbouring Britons to the south as well as invading Germanic peoples such as the Anglo-Saxons and the Norse.In modern use,...

ancestry.

Scottish

Scottish people

The Scottish people , or Scots, are a nation and ethnic group native to Scotland. Historically they emerged from an amalgamation of the Picts and Gaels, incorporating neighbouring Britons to the south as well as invading Germanic peoples such as the Anglo-Saxons and the Norse.In modern use,...

migration to New Zealand

New Zealand

New Zealand is an island country in the south-western Pacific Ocean comprising two main landmasses and numerous smaller islands. The country is situated some east of Australia across the Tasman Sea, and roughly south of the Pacific island nations of New Caledonia, Fiji, and Tonga...

dates back to the earliest period of European colonisation, with a large proportion of Pākehā

Pakeha

Pākehā is a Māori language word for New Zealanders who are "of European descent". They are mostly descended from British and to a lesser extent Irish settlers of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, although some Pākehā have Dutch, Scandinavian, German, Yugoslav or other ancestry...

New Zealanders being of Scottish descent. However, identification as "British" or "European" New Zealanders can sometimes obscure their origin. Many Scottish New Zealanders have Māori or other non-European ancestry.

Numbers

In 2006, the number of people born in Scotland was recorded as 29,016 , making it the eighth most common place of birth. In 1956, the figure was 46,401, making Scotland the second most common place of birth.However, these figures only include people born in Scotland, not those New Zealanders who claim a Scottish identity through their parents, grandparents, or even further back. In addition, many New Zealanders come from mixed origins, with Scottish New Zealanders co-identifying as Māori or another ethnic group.

In 2006, 15,039 self-identified as Scottish.

Scottish culture in New Zealand

- After one generation in New Zealand the Irish and Gaelic languages disappeared, and a more generalised loyalty to Britain developed. School pupils learnt about the heroes of Britain and read British literature. Most of this was in fact English culture, although certain Scottish writers like Walter Scott had their place. Even the Irish, who followed the fortunes of their homeland politically, played the English game of rugby football. The sense of being Britons was a necessary prelude to becoming New Zealanders.

Today, if there can be said to be a "stronghold" of Scottish culture in New Zealand, it would be in the provinces of Southland

Southland District

Southland District is a territorial authority in the South Island of New Zealand. Southland District covers the majority of the land area of Southland Region, although the region also covers Gore District, Invercargill City and adjacent territorial waters...

and Otago

Otago

Otago is a region of New Zealand in the south of the South Island. The region covers an area of approximately making it the country's second largest region. The population of Otago is...

.

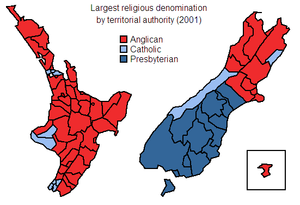

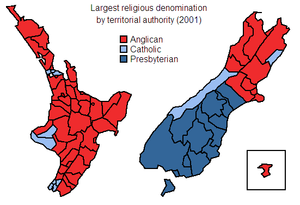

Some of the following aspects of Scottish culture can still be found in some parts of New Zealand.

- BagpipingBagpipesBagpipes are a class of musical instrument, aerophones, using enclosed reeds fed from a constant reservoir of air in the form of a bag. Though the Scottish Great Highland Bagpipe and Irish uilleann pipes have the greatest international visibility, bagpipes of many different types come from...

and pipe bandPipe bandA pipe band is a musical ensemble consisting of pipers and drummers. The term used by military pipe bands, pipes and drums, is also common....

s. - Burns SupperBurns supperA Burns supper is a celebration of the life and poetry of the poet Robert Burns, author of many Scots poems. The suppers are normally held on or near the poet's birthday, 25 January, sometimes also known as Robert Burns Day or Burns Night , although they may in principle be held at any time of the...

- CeilidhCéilidhIn modern usage, a céilidh or ceilidh is a traditional Gaelic social gathering, which usually involves playing Gaelic folk music and dancing. It originated in Ireland, but is now common throughout the Irish and Scottish diasporas...

s - HogmanayHogmanayHogmanay is the Scots word for the last day of the year and is synonymous with the celebration of the New Year in the Scottish manner...

, the Scottish New YearNew YearThe New Year is the day that marks the time of the beginning of a new calendar year, and is the day on which the year count of the specific calendar used is incremented. For many cultures, the event is celebrated in some manner.... - PresbyterianismPresbyterianismPresbyterianism refers to a number of Christian churches adhering to the Calvinist theological tradition within Protestantism, which are organized according to a characteristic Presbyterian polity. Presbyterian theology typically emphasizes the sovereignty of God, the authority of the Scriptures,...

- the majority of Scottish settlers were Presbyterian (although a substantial number were not). - TartanTartanTartan is a pattern consisting of criss-crossed horizontal and vertical bands in multiple colours. Tartans originated in woven wool, but now they are made in many other materials. Tartan is particularly associated with Scotland. Scottish kilts almost always have tartan patterns...

, some regions of NZ having their own tartan, such as OtagoOtagoOtago is a region of New Zealand in the south of the South Island. The region covers an area of approximately making it the country's second largest region. The population of Otago is...

. Additionally Scottish dress is worn by some New Zealanders to celebrate their ancestral heritage. - Tartan DayTartan DayTartan Day is a celebration of Scottish heritage on April 6, the date on which the Declaration of Arbroath was signed in 1320. A one-off event was held in New York City in 1982, but the current format originated in Canada in the mid 1980s. It spread to other communities of the Scottish diaspora in...

, in NZ, this falls on 1 July., the date of the repeal proclamation in 1792 of the Act of Proscription that banned the wear of Scottish national dress. - Lastly, some parts of South Island have a rhotic accentRhotic and non-rhotic accentsEnglish pronunciation can be divided into two main accent groups: a rhotic speaker pronounces a rhotic consonant in words like hard; a non-rhotic speaker does not...

called Southland burr, reflecting an influence from Lowland ScotsScots languageScots is the Germanic language variety spoken in Lowland Scotland and parts of Ulster . It is sometimes called Lowland Scots to distinguish it from Scottish Gaelic, the Celtic language variety spoken in most of the western Highlands and in the Hebrides.Since there are no universally accepted...

and Scottish EnglishScottish EnglishScottish English refers to the varieties of English spoken in Scotland. It may or may not be considered distinct from the Scots language. It is always considered distinct from Scottish Gaelic, a Celtic language....

, although this is less pronounced than in Scotland itself.

The Scottish Gaelic language

Scottish Gaelic language

Scottish Gaelic is a Celtic language native to Scotland. A member of the Goidelic branch of the Celtic languages, Scottish Gaelic, like Modern Irish and Manx, developed out of Middle Irish, and thus descends ultimately from Primitive Irish....

and culture did not fare well. Turakina

Turakina, New Zealand

Turakina is an old Māori settlement situated south of Whanganui city on the North Island of New Zealand. Turakina village derives its name from the Turakina River, which cut its passage to the sea from a spring on Mount Ruapehu. The original inhabitants of the area were the descendants of the Kahui...

in Wanganui

Wanganui

Whanganui , also spelled Wanganui, is an urban area and district on the west coast of the North Island of New Zealand. It is part of the Manawatu-Wanganui region....

was originally settled by Gaelic speakers, but there is not much trace other than annual Highland games.

In the past, Scottish army regiments have been raised from New Zealand, and their successor units still exist in the New Zealand Army

New Zealand Army

The New Zealand Army , is the land component of the New Zealand Defence Force and comprises around 4,500 Regular Force personnel, 2,000 Territorial Force personnel and 500 civilians. Formerly the New Zealand Military Forces, the current name was adopted around 1946...

. According to Collins Encyclopaedia of Scotland

Collins Encyclopaedia of Scotland

Collins Encyclopaedia of Scotland is a reference work published by Harper Collins, edited by the husband and wife team, John and Julia Keay.-History:...

:

- "New Zealand contains two battalions of New Zealand Scottish affiliated to the Black Watch. Their forerunners include a number of Highland Companies, and the Dunedin Highland Rifles"

The Otago and Southland Regiment

Otago and Southland Regiment

The Otago and Southland Regiment is a Territorial Force unit of the New Zealand Army. It was originally formed in 1948 by the amalgamation of two separate regiments:*Otago Regiment*Southland Regiment...

is still linked to the Highlanders in the British Army.

Otago and Southland Province

The Otago Settlement, sponsored by the Free Church of ScotlandFree Church of Scotland (1843-1900)

The Free Church of Scotland is a Scottish denomination which was formed in 1843 by a large withdrawal from the established Church of Scotland in a schism known as the "Disruption of 1843"...

, materialised in March 1848 with the arrival of the first two immigrant ships from Greenock

Greenock

Greenock is a town and administrative centre in the Inverclyde council area in United Kingdom, and a former burgh within the historic county of Renfrewshire, located in the west central Lowlands of Scotland...

on the Firth of Clyde

Firth of Clyde

The Firth of Clyde forms a large area of coastal water, sheltered from the Atlantic Ocean by the Kintyre peninsula which encloses the outer firth in Argyll and Ayrshire, Scotland. The Kilbrannan Sound is a large arm of the Firth of Clyde, separating the Kintyre Peninsula from the Isle of Arran.At...

-- the John Wickliffe

John Wickliffe (ship)

John Wickliffe was the first ship to arrive carrying Scottish settlers, including Otago settlement founder Captain William Cargill, in the city of Dunedin, New Zealand...

and the Philip Laing. Captain William Cargill

William Cargill

William Walter Cargill was the founder of the Otago settlement in New Zealand, after serving as an officer in the British Army. He was a Member of Parliament and Otago's first Superintendent.-Early life:...

, a veteran of the Peninsular War

Peninsular War

The Peninsular War was a war between France and the allied powers of Spain, the United Kingdom, and Portugal for control of the Iberian Peninsula during the Napoleonic Wars. The war began when French and Spanish armies crossed Spain and invaded Portugal in 1807. Then, in 1808, France turned on its...

, served as the colony's first leader: Otago citizens subsequently elected him to the office of Superintendent.

Provincial government in New Zealand ceased in 1876, and the national limelight gradually shifted northwards. The colony divided itself into counties in 1876, two in Otago being named after the Scottish independence heroes Wallace

William Wallace

Sir William Wallace was a Scottish knight and landowner who became one of the main leaders during the Wars of Scottish Independence....

and Bruce

Robert I of Scotland

Robert I , popularly known as Robert the Bruce , was King of Scots from March 25, 1306, until his death in 1329.His paternal ancestors were of Scoto-Norman heritage , and...

.

Originally part of Otago Province

Otago Province

The Otago Province was a province of New Zealand until the abolition of provincial government in 1876.-Area:The capital of the province was Dunedin...

, Southland Province (a small part of the present Region, centred on Invercargill

Invercargill

Invercargill is the southernmost and westernmost city in New Zealand, and one of the southernmost cities in the world. It is the commercial centre of the Southland region. It lies in the heart of the wide expanse of the Southland Plains on the Oreti or New River some 18 km north of Bluff,...

) was one of the provinces of New Zealand

Provinces of New Zealand

The Provinces of New Zealand existed from 1841 until 1876 as a form of sub-national government. They were replaced by counties, which were themselves replaced by districts.Following abolition, the provinces became known as provincial districts...

from 1861 until 1870. It rejoined Otago Province due to financial difficulties, and the provinces were abolished entirely in 1876.

In 1856, a petition was put forward to Thomas Gore Browne

Thomas Gore Browne

Colonel Sir Thomas Robert Gore Browne KCMG CB was a British colonial administrator, who was Governor of St Helena, Governor of New Zealand, Governor of Tasmania and Governor of Bermuda.-Early life:...

, the Governor of New Zealand

Governor-General of New Zealand

The Governor-General of New Zealand is the representative of the monarch of New Zealand . The Governor-General acts as the Queen's vice-regal representative in New Zealand and is often viewed as the de facto head of state....

, for a port at Bluff. Browne agreed to the petition and gave the name Invercargill

Invercargill

Invercargill is the southernmost and westernmost city in New Zealand, and one of the southernmost cities in the world. It is the commercial centre of the Southland region. It lies in the heart of the wide expanse of the Southland Plains on the Oreti or New River some 18 km north of Bluff,...

to the settlement north of the port. Inver comes from the Scots Gaelic word inbhir meaning a river's mouth and Cargill is in honour of Captain William Cargill

William Cargill

William Walter Cargill was the founder of the Otago settlement in New Zealand, after serving as an officer in the British Army. He was a Member of Parliament and Otago's first Superintendent.-Early life:...

, who was at the time the Superintendent of Otago

Otago Province

The Otago Province was a province of New Zealand until the abolition of provincial government in 1876.-Area:The capital of the province was Dunedin...

, of which Southland was then a part.

Dunedin

Free Church of Scotland (1843-1900)

The Free Church of Scotland is a Scottish denomination which was formed in 1843 by a large withdrawal from the established Church of Scotland in a schism known as the "Disruption of 1843"...

founded Dunedin at the head of Otago Harbour in 1848 as the principal town of its Scottish

Scotland

Scotland is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Occupying the northern third of the island of Great Britain, it shares a border with England to the south and is bounded by the North Sea to the east, the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, and the North Channel and Irish Sea to the...

settlement. The name comes from Dùn Èideann, the Scottish Gaelic name for Edinburgh

Edinburgh

Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland, the second largest city in Scotland, and the eighth most populous in the United Kingdom. The City of Edinburgh Council governs one of Scotland's 32 local government council areas. The council area includes urban Edinburgh and a rural area...

, the Scottish capital. Charles Kettle

Charles Kettle

Charles Henry Kettle surveyed the city of Dunedin in New Zealand, imposing a bold design on a challenging landscape. He was aiming to create a Romantic effect and incidentally produced the world's steepest street, Baldwin Street....

the city's surveyor, instructed to emulate the characteristics of Edinburgh, produced a striking, 'Romantic' design. The result was both grand and quirky streets as the builders struggled and sometimes failed to construct his bold vision across the challenging landscape. Captain William Cargill

William Cargill

William Walter Cargill was the founder of the Otago settlement in New Zealand, after serving as an officer in the British Army. He was a Member of Parliament and Otago's first Superintendent.-Early life:...

, a veteran of the war against Napoleon, was the secular leader. The Reverend Thomas Burns

Thomas Burns (New Zealand)

Thomas Burns was a prominent early European settler and religious leader of the province of Otago, New Zealand.Burns was baptised at Mauchline, Ayrshire, Scotland in April 1796, the son of estate manager Gilbert Burns, who was the brother of the poet Robert Burns...

, a nephew of the poet Robert Burns

Robert Burns

Robert Burns was a Scottish poet and a lyricist. He is widely regarded as the national poet of Scotland, and is celebrated worldwide...

, was the spiritual guide.

The Octagon

The Octagon, Dunedin

The Octagon is the city centre of Dunedin, in the South Island of New Zealand.-Features:The Octagon is an eight sided plaza bisected by the city's main street, which is called George Street to the northeast and Princes Street to the southwest...

was first laid out during Charles Kettle

Charles Kettle

Charles Henry Kettle surveyed the city of Dunedin in New Zealand, imposing a bold design on a challenging landscape. He was aiming to create a Romantic effect and incidentally produced the world's steepest street, Baldwin Street....

's surveying of the city in 1846. His plans for the centre of Dunedin included a large Octagonal area (Moray Place

Moray Place, Dunedin

Moray Place is an octagonal street which surrounds the city centre of Dunedin, Otago, New Zealand. The street is intersected by Stuart Street , Princes Street and George Street...

) enclosing a smaller octagonal shape, originally designated as a reserve. Despite the reserve status, the Church of England

Church of England

The Church of England is the officially established Christian church in England and the Mother Church of the worldwide Anglican Communion. The church considers itself within the tradition of Western Christianity and dates its formal establishment principally to the mission to England by St...

sought to build in the centre of the Octagon, applying directly to Governor

Governor-General of New Zealand

The Governor-General of New Zealand is the representative of the monarch of New Zealand . The Governor-General acts as the Queen's vice-regal representative in New Zealand and is often viewed as the de facto head of state....

Sir George Grey

George Grey

George Grey may refer to:*Sir George Grey, 2nd Baronet , British politician*George Grey, 2nd Earl of Kent *Sir George Grey , Governor of Cape Colony, South Australia and New Zealand...

. It was not until building was about to commence that the local (predominantly Scottish and Presbyterian) community became aware of what was happening. This resulted in a major furore within the city. Otago Superintendent William Cargill

William Cargill

William Walter Cargill was the founder of the Otago settlement in New Zealand, after serving as an officer in the British Army. He was a Member of Parliament and Otago's first Superintendent.-Early life:...

was put in charge of the dispute, resulting in the Anglicans being forced to withdraw their plans for The Octagon (The Anglican St. Paul's Cathedral

St. Paul's Cathedral, Dunedin

St Paul's Cathedral is the mother church of the Anglican Diocese of Dunedin, in New Zealand and the seat of the Bishop of Dunedin.-Location:The Cathedral Church of St Paul occupies a site in the heart of The Octagon near the Dunedin Town Hall and hence Dunedin...

stands today at the northern edge of The Octagon).

Many of the suburbs of Dunedin are named after their Edinburgh equivalents

Areas of Edinburgh

Edinburgh, the capital of Scotland, is divided into areas that generally encompass a park , a main local street , a high street and residential buildings...

Otago Highlanders

Scottish people

The Scottish people , or Scots, are a nation and ethnic group native to Scotland. Historically they emerged from an amalgamation of the Picts and Gaels, incorporating neighbouring Britons to the south as well as invading Germanic peoples such as the Anglo-Saxons and the Norse.In modern use,...

settlers in the lower South Island

South Island

The South Island is the larger of the two major islands of New Zealand, the other being the more populous North Island. It is bordered to the north by Cook Strait, to the west by the Tasman Sea, to the south and east by the Pacific Ocean...

. These Scottish settlers were the founders of Dunedin

Dunedin

Dunedin is the second-largest city in the South Island of New Zealand, and the principal city of the Otago Region. It is considered to be one of the four main urban centres of New Zealand for historic, cultural, and geographic reasons. Dunedin was the largest city by territorial land area until...

—known as the "Edinburgh

Edinburgh

Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland, the second largest city in Scotland, and the eighth most populous in the United Kingdom. The City of Edinburgh Council governs one of Scotland's 32 local government council areas. The council area includes urban Edinburgh and a rural area...

of the South", and the city where the Highlanders are based. According to the Highlanders official website: " The name and image of the Highlander conjures up visions of fierce independence, pride in one's roots, loyalty, strength, kinship, honesty, and hard work." The colours of the Highlanders encompasses the provincial colours of North Otago, Otago, and Southland; yellow, blue and maroon

Maroon (color)

Maroon is a dark red color.-Etymology:Maroon is derived from French marron .The first recorded use of maroon as a color name in English was in 1789.-Maroon :...

. Blue is also the predominant colour of the Flag of Scotland

Flag of Scotland

The Flag of Scotland, , also known as Saint Andrew's Cross or the Saltire, is the national flag of Scotland. As the national flag it is the Saltire, rather than the Royal Standard of Scotland, which is the correct flag for all individuals and corporate bodies to fly in order to demonstrate both...

, and is used by many sports teams in that country.

University of Otago

James Macandrew

James Macandrew was a New Zealand ship-owner and politician. He served as a Member of Parliament from 1853 to 1887 and as the last Superintendent of Otago Province.-Early life:...

urged the Otago Provincial Council during the 1860s to set aside a land endowment for an institute of higher education. An ordinance of the council established the university in 1869, giving it 100000 acres (404.7 km²) of land, and the power to grant degrees in Arts, Medicine, Law and Music. Burns was named Chancellor, but he did not live to see the university open on 5 July 1871. The university issued just one degree before becoming an affiliate college of the federal University of New Zealand

University of New Zealand

The University of New Zealand was the New Zealand university from 1870 to 1961. It was the sole New Zealand university, having a federal structure embracing several constituent colleges at various locations around New Zealand...

in 1874. With the dissolving of the University of New Zealand in 1961 and passage of the University of Otago Amendment Act 1961, the university regained authority to confer degrees.

The University's coat of arms was granted by the Lord Lyon King of Arms on 21 January 1948, and features a yellow saltire, on blue.

Notable people

See also - :Category:New Zealand people of Scottish descent- Janet FrameJanet FrameJanet Paterson Frame, ONZ, CBE was a New Zealand author. She wrote eleven novels, four collections of short stories, a book of poetry, an edition of juvenile fiction, and three volumes of autobiography during her lifetime. Since her death, a twelfth novel, a second volume of poetry, and a handful...

, born in Dunedin of Scottish parents. - William CargillWilliam CargillWilliam Walter Cargill was the founder of the Otago settlement in New Zealand, after serving as an officer in the British Army. He was a Member of Parliament and Otago's first Superintendent.-Early life:...

(28 August 1924 - 29 January 2004) - John Barr (poet)John Barr (poet)John Barr of Craigilee was a Scottish-New Zealand poet.-Biography:Born in Paisley, Scotland in 1809, Barr moved to Otago in 1852, and farmed a property at Halfway Bush. In 1857 he moved with his wife Mary and their four children to Balclutha, and established a farm which he called Craigilee. He...

, poet, wrote in Lallans - Norman McLeod (minister)

- Katie SadleirKatie SadleirCatherine Anne Grant Sadleir is a former synchronized swimmer. She competed for New Zealand at the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles with her sister Lynette Sadleir...

, Olympian, born TorphinsTorphinsTorphins is a village in Royal Deeside, Aberdeenshire, Scotland, about 20 miles west of Aberdeen. It is on the A980 road, about 6 miles north-west of Banchory, and was once served by the Great North of Scotland Railway....

. - Elizabeth Yates (mayor)Elizabeth Yates (mayor)Elizabeth Yates was the mayor of Onehunga borough in New Zealand for most of 1894. She was the first female mayor anywhere in the British Empire. Onehunga is now part of the city of Auckland.- Life :...

- Alistair Campbell (poet)Alistair Campbell (poet)Alistair Te Ariki Campbell, ONZM was a New Zealand poet, playwright, and novelist. His father was a New Zealand Scot and his mother a Cook Island Maori from Penrhyn Island.-Biography:...

- James Keir BaxterJames K. BaxterJames Keir Baxter was a poet, and is a celebrated figure in New Zealand society.-Biography:Baxter was born in Dunedin to Archibald Baxter and Millicent Brown and grew up near Brighton. He was named after James Keir Hardie, a founder of the British Labour Party. His father had been a conscientious...

, writer - Winston PetersWinston PetersWinston Raymond Peters is a New Zealand politician and leader of New Zealand First, a political party he founded in 1993. Peters has had a turbulent political career since entering Parliament in 1978. He served as Minister of Maori Affairs in the Bolger National Party Government before being...

, New Zealand FirstNew Zealand FirstNew Zealand First is a political party in New Zealand that was founded in 1993, following party founder Winston Peters' resignation from the National Party in 1992...

politician, of Scottish and Maori roots. - Minnie DeanMinnie DeanWilliamina "Minnie" Dean was a New Zealander who was found guilty of infanticide and hanged. She was the only woman to receive the death penalty in New Zealand....

(1844-1895) murderer, and the only woman to receive the death penaltyCapital punishmentCapital punishment, the death penalty, or execution is the sentence of death upon a person by the state as a punishment for an offence. Crimes that can result in a death penalty are known as capital crimes or capital offences. The term capital originates from the Latin capitalis, literally...

in New Zealand, born GreenockGreenockGreenock is a town and administrative centre in the Inverclyde council area in United Kingdom, and a former burgh within the historic county of Renfrewshire, located in the west central Lowlands of Scotland...

. - James Mckenzie, possibly born in Ross-shireRoss-shireRoss-shire is an area in the Highland Council Area in Scotland. The name is now used as a geographic or cultural term, equivalent to Ross. Until 1889 the term denoted a county of Scotland, also known as the County of Ross...

, ScotlandScotlandScotland is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Occupying the northern third of the island of Great Britain, it shares a border with England to the south and is bounded by the North Sea to the east, the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, and the North Channel and Irish Sea to the...

, in 1820 was a New ZealandNew ZealandNew Zealand is an island country in the south-western Pacific Ocean comprising two main landmasses and numerous smaller islands. The country is situated some east of Australia across the Tasman Sea, and roughly south of the Pacific island nations of New Caledonia, Fiji, and Tonga...

outlawOutlawIn historical legal systems, an outlaw is declared as outside the protection of the law. In pre-modern societies, this takes the burden of active prosecution of a criminal from the authorities. Instead, the criminal is withdrawn all legal protection, so that anyone is legally empowered to persecute...

who has become one of the country's most enduring folk heroes. - Kate SheppardKate SheppardKatherine Wilson Sheppard Some sources, eg give a birth year of 1847; others eg give a birth year of 1848. was the most prominent member of New Zealand's women's suffrage movement, and is the country's most famous suffragette...

, suffragette, born in LiverpoolLiverpoolLiverpool is a city and metropolitan borough of Merseyside, England, along the eastern side of the Mersey Estuary. It was founded as a borough in 1207 and was granted city status in 1880...

to Scottish parents. - George Smith DuncanGeorge Smith DuncanGeorge Smith Duncan was a tramway and mining engineer best known for his work on cable trams, and for his work in the gold mining industry.Duncan was born in the New Zealand city of Dunedin in 1852, the son of recent Scottish immigrants...

- Elizabeth Grace NeillElizabeth Grace NeillElizabeth Grace Neill was a nurse from New Zealand who lobbied for passage of laws requiring training and registration of nurses and midwives in New Zealand. The nursing experience she received during her early life inspired her to reform many aspects of the nursing practice...

, lobbied for passage of laws requiring training and registration of nurses and midwives in New Zealand.

Prime Ministers

Many of the prime ministers of New Zealand have been of Scottish descent. They include:- Robert StoutRobert StoutSir Robert Stout, KCMG was the 13th Premier of New Zealand on two occasions in the late 19th century, and later Chief Justice of New Zealand. He was the only person to hold both these offices...

(1844-1930), born LerwickLerwickLerwick is the capital and main port of the Shetland Islands, Scotland, located more than 100 miles off the north coast of mainland Scotland on the east coast of the Shetland Mainland... - Thomas MackenzieThomas MackenzieSir Thomas Noble Mackenzie GCMG was a Scottish-born New Zealand politician and explorer who briefly served as the 18th Prime Minister of New Zealand in 1912, and later served as New Zealand High Commissioner in London....

(1854-1930), born EdinburghEdinburghEdinburgh is the capital city of Scotland, the second largest city in Scotland, and the eighth most populous in the United Kingdom. The City of Edinburgh Council governs one of Scotland's 32 local government council areas. The council area includes urban Edinburgh and a rural area... - Peter Fraser (1884 - 1950), born TainTainTain is a royal burgh and post town in the committee area of Ross and Cromarty, in the Highland area of Scotland.-Etymology:...

- Edward Stafford (politician)Edward Stafford (politician)Sir Edward Stafford, KCMG served as the third Premier of New Zealand on three occasions in the mid 19th century. His total time in office is the longest of any leader without a political party. He is described as pragmatic, logical, and clear-sighted.-Early life and career:Edward William Stafford...

, on three occasions in the mid 19th century, born Edinburgh.

"Kilted Kiwis"

"Kilted Kiwi" is a nickname given to New Zealanders who would go on to play in the Scotland national rugby union teamScotland national rugby union team

The Scotland national rugby union team represent Scotland in international rugby union. Rugby union in Scotland is administered by the Scottish Rugby Union. The Scotland rugby union team is currently ranked eighth in the IRB World Rankings as of 19 September 2011...

. They have had a mixed reception, but have included some notable players. The original "kilted Kiwi" was Sean Lineen

Sean Lineen

Sean Lineen is a Scottish rugby player, originally from New Zealand. He has been awarded the freedom of the city of Edinburgh.-Early life:Lineen was born on December 25, 1961, in Auckland. He is the son of rugby player Terry Lineen....

. In order to qualify, they either have to have at least one Scottish parent or grandparent.

Other so-called "kilted Kiwis" apart from Sean Lineen have included:

- Brendan LaneyBrendan LaneyBrendan James Laney, is a former professional rugby union player who represented Scotland. Nicknamed "Chainsaw" for the way he cut through defences, he was also a good goal kicker. From Southland in New Zealand, he began his professional rugby career at full back for the Highlanders in the Super 12...

- John LeslieJohn Leslie (rugby player)John Andrew Leslie is a former rugby union footballer who played at centre for Scotland. He is the elder son of Andy Leslie the great All Blacks captain and the brother of Martin Leslie who also played for Scotland...

- Martin LeslieMartin Leslie (rugby player)Martin Leslie is a New Zealand born former professional rugby union player who played provincial rugby for Wellington and the Hurricanes before moving to play international rugby for Scotland, for whom he qualified through grandparents. He played primarily in the back row, winning 37 caps between...

- Glenn MetcalfeGlenn MetcalfeGlenn Hayden Metcalfe is a former rugby union footballer who played at fullback for Glasgow, Castres and Scotland.-Career:...

- Gordon SimpsonGordon SimpsonGordon Leslie Simpson is a former Australian politician.Simpson was the National Party member for Cooroora from 1974 to 1989 and served as Minister for Mines and Energy and Minister from the Arts from 25 November to 1 December 1987. His daughter, Fiona Simpson, was also a National Party...

However, this has not always been a one way trade. At least one All Black was born in Scotland - Angus Stuart

Angus Stuart

Angus John Stuart also known as Angus Stewart was a Scottish-born rugby union forward who played club rugby for Cardiff and Dewsbury. Although never capped at international level in his own country, in 1888 Stuart was chosen to tour New Zealand and Australia as part of the first British Isles team...

.

Scottish placenames

South Island

The South Island is the larger of the two major islands of New Zealand, the other being the more populous North Island. It is bordered to the north by Cook Strait, to the west by the Tasman Sea, to the south and east by the Pacific Ocean...

. Notable Scottish placenames in New Zealand include:

- North Island

- Hamilton, New ZealandHamilton, New ZealandHamilton is the centre of New Zealand's fourth largest urban area, and Hamilton City is the country's fourth largest territorial authority. Hamilton is in the Waikato Region of the North Island, approximately south of Auckland...

- Napier, New ZealandNapier, New ZealandNapier is a New Zealand city with a seaport, located in Hawke's Bay on the eastern coast of the North Island. The population of Napier is about About 18 kilometres south of Napier is the inland city of Hastings. These two neighboring cities are often called "The Twin Cities" or "The Bay Cities"...

- Hamilton, New Zealand

- South Island

- DunedinDunedinDunedin is the second-largest city in the South Island of New Zealand, and the principal city of the Otago Region. It is considered to be one of the four main urban centres of New Zealand for historic, cultural, and geographic reasons. Dunedin was the largest city by territorial land area until...

, from Dun Eideann, the Scottish Gaelic for Edinburgh. The town was originally to be called "New Edinburgh". Many of its street and suburb names mirror those of Edinburgh. - InvercargillInvercargillInvercargill is the southernmost and westernmost city in New Zealand, and one of the southernmost cities in the world. It is the commercial centre of the Southland region. It lies in the heart of the wide expanse of the Southland Plains on the Oreti or New River some 18 km north of Bluff,...

, from "Inver" meaning a river mouth (an anglicisation of the Scottish Gaelic Inbhir), plus "Cargill". - BalcluthaBalclutha, New ZealandBalclutha is a town in Otago, it lies towards the end of the Clutha River on the east coast of the South Island of New Zealand. It is about halfway between Dunedin and Invercargill on the Main South Line railway, State Highway 1 and the Southern Scenic Route...

, from Baile Chluaidh meaning the town on the river Clutha (Abhainn Chluaidh - River ClydeRiver ClydeThe River Clyde is a major river in Scotland. It is the ninth longest river in the United Kingdom, and the third longest in Scotland. Flowing through the major city of Glasgow, it was an important river for shipbuilding and trade in the British Empire....

.) - Lammerlaw Range (mountains)

- The Grampians (mountains)

- ObanOban, New ZealandOban is the principal settlement on Stewart Island/Rakiura, the southernmost inhabited island of the New Zealand archipelago. Oban is located on Halfmoon Bay , on Paterson Inlet...

, the "capital" and only town of Stewart Island/Rakiura. - Ulva IslandUlva Island, New ZealandUlva Island is a small island about long lying within Paterson Inlet, which is part of Stewart Island/Rakiura in New Zealand. It has an area of about , the majority of which is public land...

- Water of LeithWater of Leith, New ZealandThe Water of Leith , is a small river in the South Island of New Zealand.It rises to the north of the city of Dunedin, flowing for 14 kilometres southeast through the northern part of the city and the campus of the University of Otago before reaching the Otago Harbour...

(river)

- Dunedin

The South Island also contains the Strath-Taieri and the Ben Ohau Range

Ben Ohau Range

Ben Ohau Range is a mountain range in Canterbury Region, South Island, New Zealand. It lies west of Lake Pukaki, at .- External links :*...

of mountains, both combining Scots Gaelic and Maori

Maori language

Māori or te reo Māori , commonly te reo , is the language of the indigenous population of New Zealand, the Māori. It has the status of an official language in New Zealand...

origins. Invercargill

Invercargill

Invercargill is the southernmost and westernmost city in New Zealand, and one of the southernmost cities in the world. It is the commercial centre of the Southland region. It lies in the heart of the wide expanse of the Southland Plains on the Oreti or New River some 18 km north of Bluff,...

has the appearance of a Scottish name, since it combines the Scottish prefix "Inver" (Inbhir), meaning a river's mouth, with "Cargill", the name of a Scottish official. (Many of Invercargill's main streets are named after Scottish rivers: Dee, Tay, Spey, Esk, Don, Doon, Clyde, etc.). Inchbonnie

Inchbonnie

Inchbonnie is a rural locality in the West Coast region of New Zealand's South Island."Inchbonnie" is a hybrid of Lowland Scots, bonnie meaning "pretty" and Scottish Gaelic innis meaning island, often anglicised as "Inch", as in Inchkeith or Inchkenneth in Scotland.It allegedly receives 6 m of rain...

is a hybrid of Lowland Scots

Scots language

Scots is the Germanic language variety spoken in Lowland Scotland and parts of Ulster . It is sometimes called Lowland Scots to distinguish it from Scottish Gaelic, the Celtic language variety spoken in most of the western Highlands and in the Hebrides.Since there are no universally accepted...

and Scottish Gaelic

In popular culture

- An Angel at My TableAn Angel at My TableAn Angel at My Table is a 1990 New Zealand-Australian-British film directed by Jane Campion. The film is based on Janet Frame's three autobiographies, To the Is-Land , An Angel at My Table , and The Envoy from Mirror City ....

(1990), is a fictionalised film version of Janet FrameJanet FrameJanet Paterson Frame, ONZ, CBE was a New Zealand author. She wrote eleven novels, four collections of short stories, a book of poetry, an edition of juvenile fiction, and three volumes of autobiography during her lifetime. Since her death, a twelfth novel, a second volume of poetry, and a handful...

's autobiographical works, and deals with her family life. - Black SheepBlack Sheep (2007 film)Black Sheep is a New Zealand made comedy horror film written and directed by Jonathan King. North American distribution rights were acquired by The Weinstein Company and IFC Films. The Weinstein Company released the film on DVD on 9 October 2007 under their Dimension Extreme brand through Genius...

(2007), a comedy horror, which features the Oldfields, a family of Scottish New Zealanders who live on a farm called "Glenolden". The villain is called Angus, and it also features a scene in which haggisHaggisHaggis is a dish containing sheep's 'pluck' , minced with onion, oatmeal, suet, spices, and salt, mixed with stock, and traditionally simmered in the animal's stomach for approximately three hours. Most modern commercial haggis is prepared in a casing rather than an actual stomach.Haggis is a kind...

is being made. - A novel based partly on James Mckenzie's life, Chandler's Run, by Denise Muir, was published in 2008.

- The PianoThe PianoThe Piano is a 1993 New Zealand drama film about a mute pianist and her daughter, set during the mid-19th century in a rainy, muddy frontier backwater on the west coast of New Zealand. The film was written and directed by Jane Campion, and stars Holly Hunter, Harvey Keitel, Sam Neill, and Anna Paquin...

(1993) tells the story of a silent but strongwilled Scotswoman, Ada McGrath (played by Holly HunterHolly HunterHolly Hunter is an American actress. Hunter starred in The Piano for which she won the Academy Award for Best Actress. She has also been nominated for Oscars for her roles in Broadcast News, The Firm, and Thirteen...

), whose father arranges a marriage to New Zealand frontiersman Alistair Stewart (portrayed by Sam NeillSam NeillNigel John Dermot "Sam" Neill, DCNZM, OBE is a New Zealand actor. He is well known for his starring role as paleontologist Dr Alan Grant in Jurassic Park and Jurassic Park III....

).

See also

- Demographics of New ZealandDemographics of New ZealandThe demographics of New Zealand encompass the gender, ethnic, religious, geographic, and economic backgrounds of the 4.4 million people living in New Zealand. New Zealanders, informally known as "Kiwis", predominantly live in urban areas within the North Island...

- Immigration to New ZealandImmigration to New ZealandImmigration to New Zealand began with Polynesian settlement in New Zealand, then uninhabited, in the tenth century . The role of Moriori settlement is currently disputed, with some suggesting that the Moriori arrived in New Zealand before the Maori, and were distinct from Maori, & others favouring...

- Europeans in OceaniaEuropeans in OceaniaEuropean exploration and settlement of Oceania began in the 16th century, starting with Spanish landings and shipwrecks in the Marianas Islands, east of the Philippines. Subsequent rivalry between European colonial powers, trade opportunities and Christian missions drove further European...

- New Zealand EuropeanNew Zealand EuropeanThe term New Zealand European refers to New Zealanders of European descent who identify as New Zealand Europeans rather than some other ethnic group...

- History of New ZealandHistory of New ZealandThe history of New Zealand dates back at least 700 years to when it was discovered and settled by Polynesians, who developed a distinct Māori culture centred on kinship links and land. The first European explorer to discover New Zealand was Abel Janszoon Tasman on 13 December 1642...

- PākehāPakehaPākehā is a Māori language word for New Zealanders who are "of European descent". They are mostly descended from British and to a lesser extent Irish settlers of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, although some Pākehā have Dutch, Scandinavian, German, Yugoslav or other ancestry...