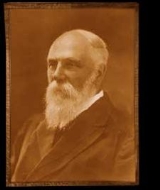

Robert Stout

Encyclopedia

Sir Robert Stout, KCMG

(28 September 1844 – 19 July 1930) was the 13th Premier of New Zealand

on two occasions in the late 19th century, and later Chief Justice of New Zealand

. He was the only person to hold both these offices. He was noted for his support of liberal causes such as women's suffrage

, and for his strong belief that philosophy and theory should always triumph over political expediency.

, in Scotland

's Shetland Islands

. He retained a strong attachment to the Shetland Islands throughout his life. He was given a good education, and eventually qualified as a teacher. He also qualified as a surveyor in 1860. He became highly interested in politics through his extended family, which often met to discuss and debate political issues of the day. Stout was exposed to many different political philosophies during his youth.

In 1863, Stout emigrated to Dunedin, New Zealand. Once there, Stout quickly became involved in political debate, which he greatly enjoyed. He also became active in the Freethought

circles of the city. After failing to find employment as a surveyor on the Otago

gold field

s, Stout returned to education, holding a number of senior teaching positions at the high school level.

Eventually, however, Stout moved away from education and entered the legal profession

. In 1867, Stout was working in the law firm of William Downie Stewart, Sr. (father of the William Downie Stewart, Jr. who later became Minister of Finance

). He was called to the Bar in 1871, and proved to be a highly successful trial lawyer. He also became one of Otago University

's first students (possibly the first, although this claim is disputed), studying political economy

and the theory of morality

. He later became the university's first law lecturer.

. During his time on the Council, he impressed many people with both his energy and his rhetorical skill, although others found him to be abrasive, and complained about his lack of respect for those who held different views.

Stout successfully contested an August 1875 by-election in the Caversham electorate

and thus became a Member of the New Zealand Parliament. He unsuccessfully opposed moves by the central government (Vogel

) to abolish the provinces

. At the 1875–76 election a few months later, he was returned in the City of Dunedin

electorate.

On 13 March 1878, Stout became Attorney General in the government of Premier George Grey

. He was involved in a number of significant pieces of legislation while in this role. On 25 July 1878, Stout was given the additional role of Minister of Lands and Immigration. A strong advocate of land reform, Stout worked towards the goal of state ownership of land, which would then be leased to individual farmers. He often expressed fears that private ownership would lead to the sort of "powerful landlord class" that existed in Britain.

On 25 June 1879, however, Stout resigned both from cabinet and from parliament, citing the need to focus on his law practice. His partner in the practice was growing increasingly ill, and the success of his firm was important to the welfare of both Stout and his family. Throughout his career, Stout found the cost of participating in politics a serious worry. His legal career, however, was probably not the only contributing factor to his resignation, with a falling out between Stout and George Grey having occurred shortly beforehand.

At around this time, Stout also developed a friendship with John Ballance

, who had also resigned from Grey's cabinet after a dispute. Stout and Ballance shared many of the same political views. During his absence from parliament, Stout began to form ideas about political parties in New Zealand, believing in the need for a united liberal front. He eventually concluded, however, that parliament was too fragmented for any real political parties to be established.

In the election of 1884

, Stout re-entered parliament, and attempted to rally the various liberal-leaning MPs behind him. Stout promptly formed an alliance with Julius Vogel

, a former premier – this surprised many observers, because although Vogel shared Stout's progressive social views, the two had frequently clashed over economic policy and the future of the provincial governments. Many believed that Vogel was the dominant partner in the alliance.

, and assumed the premiership. Julius Vogel

was made treasurer, thereby gaining a considerable measure of power in the administration. Stout's new government lasted less than two weeks, however, with Atkinson managing to pass his own vote of no confidence against Stout. Atkinson himself, however, failed to establish a government, and was removed by yet another vote of no confidence. Stout and Vogel returned to power once again.

Stout's second government lasted considerably longer than his first. Its primary achievements were the reform of the civil service and a program to increase the number of secondary schools in the country. It also organised the construction of the Midland

railway line between Canterbury

and the West Coast

. The economy, however, did not prosper, with all attempts to pull it out of depression failing. In the 1887 election

, Stout himself lost his seat in parliament to James Allen

by twenty-nine votes, thereby ending his premiership. Harry Atkinson, Stout's old rival, was able to form a new government after the election.

At this point, Stout decided to leave parliamentary politics altogether, and instead focus on other avenues for promoting liberal views. In particular, he was interested in resolving the growing labour disputes of the time. He was highly active in building consensus between the growing labour movement and the world of middle-class liberalism.

, Ballance had gained enough support to topple Atkinson and take the premiership. Shortly afterwards, Ballance founded the Liberal Party

, New Zealand's first real political party. Only a few years later, however, Ballance became seriously ill, and asked Stout to return to parliament and be his successor. Stout agreed, and Ballance died shortly thereafter.

Stout re-entered parliament after a winning a by-election in Inangahua

on 8 June 1893. Ballance's deputy, Richard Seddon

, had by this time assumed leadership of the party on the understanding that a full caucus

vote would later be held. In the end, however, no vote was held. Stout, backed by those who considered Seddon too conservative, attempted to challenge this, but was ultimately unsuccessful. Many of Seddon's supporters believed that the progressive views of Ballance and Stout were too extreme for the New Zealand public.

Stout remained in the Liberal Party, but constantly voiced objections to Seddon's leadership. In addition to claiming that Seddon was betraying Ballance's original progressive ideals, Stout also claimed that Seddon was too autocratic in his style of rule. Ballance's idea of a united progressive front, Stout believed, had been subverted into nothing more than a vehicle for the conservative Seddon. Seddon defended himself against these charges by claiming that Stout was merely bitter about not gaining the leadership.

. Stout had long been a supporter of this cause, having campaigned tirelessly for his own failed bill in 1878 and Julius Vogel's failed bill in 1887. He had also been highly active in the campaign to increase property rights for women, having been particularly concerned with the right of married women to keep property independently from their husbands.

John Ballance had been a supporter of women's suffrage, although his attempts to pass a bill had been blocked by the conservative Legislative Council

(the now-abolished upper house of Parliament). Seddon, however, was opposed, and many believed that the cause was now lost. However, a major initiative by suffragette

s led by Kate Sheppard

generated considerable support for women's suffrage, and Stout believed that a bill could be passed despite Seddon's objection. A group of progressive politicians, including Stout, successfully passed a women's suffrage bill in 1893 through both the lower and upper houses, with the upper house narrowly passing it after some members who had not been in favour changed their votes because of Seddon's attempts to "kill" the bill in the upper house.

Stout was also involved with the failing Walter Guthrie group of companies in Southland and Otago which had been supported by the Bank of New Zealand

, and (according to Bourke) Seddon was prepared to conceal Stout’s involvement – provided Stout left politics.

In 1898 Stout retired from politics. He had represented the seats of Caversham

in the 5th parliament

(1875), Dunedin East

in the 6th parliament

(1875–79) and in the 9th parliament

(1884–87), Inangahua

in the 11th parliament

(1893), and the City of Wellington

in the 12th and 13th parliaments (1893–98).

, and remained in this position until 31 January 1926. As of 2011, Stout was the last Chief Justice of New Zealand to have served in the Parliament of New Zealand

.

While Chief Justice, Stout showed a particular interest in the rehabilitation

of criminals, contrasting with the emphasis on punishment

that prevailed at the time. He took a leading part in the consolidation of New Zealand statutes (completed in 1908), and was made a Privy Councillor in 1921. In the same year as his retirement, Stout was appointed to the Legislative Council

, the last political office he would hold.

Stout also had a role of considerable importance in the development of the New Zealand university system. He had become a member of the Senate of the University of New Zealand

in 1885, and remained so until 1930. From 1903 to 1923, he was the university's Chancellor. He was also prominent in Otago University

from 1891 to 1898, serving on its Council. He played a very significant role in the founding of what is now Victoria University of Wellington

– the strong connection between Victoria University and the Stout family is remembered by the university's Stout Research Centre and its Robert Stout Building.

In 1929, Stout became increasingly ill, and never recovered. On 19 July 1930 he died in Wellington. He had been made a K.C.M.G. in 1886.

Order of St Michael and St George

The Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George is an order of chivalry founded on 28 April 1818 by George, Prince Regent, later George IV of the United Kingdom, while he was acting as Prince Regent for his father, George III....

(28 September 1844 – 19 July 1930) was the 13th Premier of New Zealand

Prime Minister of New Zealand

The Prime Minister of New Zealand is New Zealand's head of government consequent on being the leader of the party or coalition with majority support in the Parliament of New Zealand...

on two occasions in the late 19th century, and later Chief Justice of New Zealand

Chief Justice of New Zealand

The Chief Justice of New Zealand is the head of the New Zealand judiciary, and presides over the Supreme Court of New Zealand. Before the establishment of the latter court in 2004 the Chief Justice was the presiding judge in the High Court of New Zealand and was also ex officio a member of the...

. He was the only person to hold both these offices. He was noted for his support of liberal causes such as women's suffrage

Women's suffrage

Women's suffrage or woman suffrage is the right of women to vote and to run for office. The expression is also used for the economic and political reform movement aimed at extending these rights to women and without any restrictions or qualifications such as property ownership, payment of tax, or...

, and for his strong belief that philosophy and theory should always triumph over political expediency.

Early life

Stout was born in the town of LerwickLerwick

Lerwick is the capital and main port of the Shetland Islands, Scotland, located more than 100 miles off the north coast of mainland Scotland on the east coast of the Shetland Mainland...

, in Scotland

Scotland

Scotland is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Occupying the northern third of the island of Great Britain, it shares a border with England to the south and is bounded by the North Sea to the east, the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, and the North Channel and Irish Sea to the...

's Shetland Islands

Shetland Islands

Shetland is a subarctic archipelago of Scotland that lies north and east of mainland Great Britain. The islands lie some to the northeast of Orkney and southeast of the Faroe Islands and form part of the division between the Atlantic Ocean to the west and the North Sea to the east. The total...

. He retained a strong attachment to the Shetland Islands throughout his life. He was given a good education, and eventually qualified as a teacher. He also qualified as a surveyor in 1860. He became highly interested in politics through his extended family, which often met to discuss and debate political issues of the day. Stout was exposed to many different political philosophies during his youth.

In 1863, Stout emigrated to Dunedin, New Zealand. Once there, Stout quickly became involved in political debate, which he greatly enjoyed. He also became active in the Freethought

Freethought

Freethought is a philosophical viewpoint that holds that opinions should be formed on the basis of science, logic, and reason, and should not be influenced by authority, tradition, or other dogmas...

circles of the city. After failing to find employment as a surveyor on the Otago

Otago

Otago is a region of New Zealand in the south of the South Island. The region covers an area of approximately making it the country's second largest region. The population of Otago is...

gold field

Gold mining

Gold mining is the removal of gold from the ground. There are several techniques and processes by which gold may be extracted from the earth.-History:...

s, Stout returned to education, holding a number of senior teaching positions at the high school level.

Eventually, however, Stout moved away from education and entered the legal profession

Lawyer

A lawyer, according to Black's Law Dictionary, is "a person learned in the law; as an attorney, counsel or solicitor; a person who is practicing law." Law is the system of rules of conduct established by the sovereign government of a society to correct wrongs, maintain the stability of political...

. In 1867, Stout was working in the law firm of William Downie Stewart, Sr. (father of the William Downie Stewart, Jr. who later became Minister of Finance

Minister of Finance (New Zealand)

The Minister of Finance is a senior figure within the government of New Zealand. The position is often considered to be the most important Cabinet role after that of the Prime Minister....

). He was called to the Bar in 1871, and proved to be a highly successful trial lawyer. He also became one of Otago University

University of Otago

The University of Otago in Dunedin is New Zealand's oldest university with over 22,000 students enrolled during 2010.The university has New Zealand's highest average research quality and in New Zealand is second only to the University of Auckland in the number of A rated academic researchers it...

's first students (possibly the first, although this claim is disputed), studying political economy

Political economy

Political economy originally was the term for studying production, buying, and selling, and their relations with law, custom, and government, as well as with the distribution of national income and wealth, including through the budget process. Political economy originated in moral philosophy...

and the theory of morality

Morality

Morality is the differentiation among intentions, decisions, and actions between those that are good and bad . A moral code is a system of morality and a moral is any one practice or teaching within a moral code...

. He later became the university's first law lecturer.

Early political career

Stout's political career came when he was elected to the Otago Provincial CouncilOtago Province

The Otago Province was a province of New Zealand until the abolition of provincial government in 1876.-Area:The capital of the province was Dunedin...

. During his time on the Council, he impressed many people with both his energy and his rhetorical skill, although others found him to be abrasive, and complained about his lack of respect for those who held different views.

Stout successfully contested an August 1875 by-election in the Caversham electorate

Caversham (New Zealand electorate)

Caversham was a parliamentary electorate in the city of Dunedin in the Otago Region of New Zealand, from 1866 to 1908.-History:Caversham was first established in 1866 and abolished in 1890. It was recreated in 1893 and abolished again in 1908....

and thus became a Member of the New Zealand Parliament. He unsuccessfully opposed moves by the central government (Vogel

Julius Vogel

Sir Julius Vogel, KCMG was the eighth Premier of New Zealand. His administration is best remembered for the issuing of bonds to fund railway construction and other public works...

) to abolish the provinces

Provinces of New Zealand

The Provinces of New Zealand existed from 1841 until 1876 as a form of sub-national government. They were replaced by counties, which were themselves replaced by districts.Following abolition, the provinces became known as provincial districts...

. At the 1875–76 election a few months later, he was returned in the City of Dunedin

Dunedin (New Zealand electorate)

Dunedin or the City of Dunedin or the Town of Dunedin was a parliamentary electorate in the city of Dunedin in Otago, New Zealand. It was one of the original electorates created in 1853 and existed, with two breaks, until 1905. Most of the time, it was a multi-member electorate.-History:From 1853...

electorate.

On 13 March 1878, Stout became Attorney General in the government of Premier George Grey

George Grey

George Grey may refer to:*Sir George Grey, 2nd Baronet , British politician*George Grey, 2nd Earl of Kent *Sir George Grey , Governor of Cape Colony, South Australia and New Zealand...

. He was involved in a number of significant pieces of legislation while in this role. On 25 July 1878, Stout was given the additional role of Minister of Lands and Immigration. A strong advocate of land reform, Stout worked towards the goal of state ownership of land, which would then be leased to individual farmers. He often expressed fears that private ownership would lead to the sort of "powerful landlord class" that existed in Britain.

On 25 June 1879, however, Stout resigned both from cabinet and from parliament, citing the need to focus on his law practice. His partner in the practice was growing increasingly ill, and the success of his firm was important to the welfare of both Stout and his family. Throughout his career, Stout found the cost of participating in politics a serious worry. His legal career, however, was probably not the only contributing factor to his resignation, with a falling out between Stout and George Grey having occurred shortly beforehand.

At around this time, Stout also developed a friendship with John Ballance

John Ballance

John Ballance served as the 14th Premier of New Zealand at the end of the 19th century, and was the founder of the Liberal Party .-Early life:...

, who had also resigned from Grey's cabinet after a dispute. Stout and Ballance shared many of the same political views. During his absence from parliament, Stout began to form ideas about political parties in New Zealand, believing in the need for a united liberal front. He eventually concluded, however, that parliament was too fragmented for any real political parties to be established.

In the election of 1884

New Zealand general election, 1884

The New Zealand general election of 1884 was held on 22 July to elect a total of 95 MPs to the 9th session of the New Zealand Parliament. The Māori vote was held on 21 July. A total number of 137,686 voters turned out to vote.-References:...

, Stout re-entered parliament, and attempted to rally the various liberal-leaning MPs behind him. Stout promptly formed an alliance with Julius Vogel

Julius Vogel

Sir Julius Vogel, KCMG was the eighth Premier of New Zealand. His administration is best remembered for the issuing of bonds to fund railway construction and other public works...

, a former premier – this surprised many observers, because although Vogel shared Stout's progressive social views, the two had frequently clashed over economic policy and the future of the provincial governments. Many believed that Vogel was the dominant partner in the alliance.

Premier

In August 1884, only a month after returning to parliament, Stout successfully passed a vote of no confidence in the conservative Harry AtkinsonHarry Atkinson

Henry Albert "Harry" Atkinson served as the tenth Premier of New Zealand on four separate occasions in the late 19th century, and was Colonial Treasurer for a total of ten years...

, and assumed the premiership. Julius Vogel

Julius Vogel

Sir Julius Vogel, KCMG was the eighth Premier of New Zealand. His administration is best remembered for the issuing of bonds to fund railway construction and other public works...

was made treasurer, thereby gaining a considerable measure of power in the administration. Stout's new government lasted less than two weeks, however, with Atkinson managing to pass his own vote of no confidence against Stout. Atkinson himself, however, failed to establish a government, and was removed by yet another vote of no confidence. Stout and Vogel returned to power once again.

Stout's second government lasted considerably longer than his first. Its primary achievements were the reform of the civil service and a program to increase the number of secondary schools in the country. It also organised the construction of the Midland

Midland Line, New Zealand

The Midland line is a 212 km section of railway between Rolleston and Greymouth in the South Island of New Zealand. The line features five major bridges, five viaducts and 17 tunnels, the longest of which is the Otira tunnel.-Freight services:...

railway line between Canterbury

Canterbury, New Zealand

The New Zealand region of Canterbury is mainly composed of the Canterbury Plains and the surrounding mountains. Its main city, Christchurch, hosts the main office of the Christchurch City Council, the Canterbury Regional Council - called Environment Canterbury - and the University of Canterbury.-...

and the West Coast

West Coast, New Zealand

The West Coast is one of the administrative regions of New Zealand, located on the west coast of the South Island, and is one of the more remote and most sparsely populated areas of the country. It is made up of three districts: Buller, Grey and Westland...

. The economy, however, did not prosper, with all attempts to pull it out of depression failing. In the 1887 election

New Zealand general election, 1887

The New Zealand general election of 1887 was held on 26 September to elect 95 MPs to the tenth session of the New Zealand Parliament. The Māori vote was held on 7 September. 175,410 votes were cast....

, Stout himself lost his seat in parliament to James Allen

James Allen (New Zealand)

Sir James Allen, GCMG, KCB was a prominent New Zealand politician and diplomat. He held a number of the most important political offices in the country, including Minister of Finance and Minister of Foreign Affairs. He was also New Zealand's Minister of Defence during World War I.-Early life:Allen...

by twenty-nine votes, thereby ending his premiership. Harry Atkinson, Stout's old rival, was able to form a new government after the election.

At this point, Stout decided to leave parliamentary politics altogether, and instead focus on other avenues for promoting liberal views. In particular, he was interested in resolving the growing labour disputes of the time. He was highly active in building consensus between the growing labour movement and the world of middle-class liberalism.

Liberal Party

During Stout's absence from politics, his old ally, John Ballance, had been continuing to fight in parliament. After the 1890 electionNew Zealand general election, 1890

The New Zealand general election of 1890 was one of New Zealand's most significant. It marked the beginning of party politics in New Zealand with the formation of the First Liberal government, which was to enact major welfare, labour and electoral reforms, including giving the vote to women.It was...

, Ballance had gained enough support to topple Atkinson and take the premiership. Shortly afterwards, Ballance founded the Liberal Party

New Zealand Liberal Party

The New Zealand Liberal Party is generally regarded as having been the first real political party in New Zealand. It governed from 1891 until 1912. Out of office, the Liberals gradually found themselves pressed between the conservative Reform Party and the growing Labour Party...

, New Zealand's first real political party. Only a few years later, however, Ballance became seriously ill, and asked Stout to return to parliament and be his successor. Stout agreed, and Ballance died shortly thereafter.

Stout re-entered parliament after a winning a by-election in Inangahua

Inangahua (New Zealand electorate)

Inangahua was a former parliamentary electorate in the Buller District, which is part of the West Coast region of New Zealand, from 1881 to 1896...

on 8 June 1893. Ballance's deputy, Richard Seddon

Richard Seddon

Richard John Seddon , sometimes known as King Dick, is to date the longest serving Prime Minister of New Zealand. He is regarded by some, including historian Keith Sinclair, as one of New Zealand's greatest political leaders....

, had by this time assumed leadership of the party on the understanding that a full caucus

Caucus

A caucus is a meeting of supporters or members of a political party or movement, especially in the United States and Canada. As the use of the term has been expanded the exact definition has come to vary among political cultures.-Origin of the term:...

vote would later be held. In the end, however, no vote was held. Stout, backed by those who considered Seddon too conservative, attempted to challenge this, but was ultimately unsuccessful. Many of Seddon's supporters believed that the progressive views of Ballance and Stout were too extreme for the New Zealand public.

Stout remained in the Liberal Party, but constantly voiced objections to Seddon's leadership. In addition to claiming that Seddon was betraying Ballance's original progressive ideals, Stout also claimed that Seddon was too autocratic in his style of rule. Ballance's idea of a united progressive front, Stout believed, had been subverted into nothing more than a vehicle for the conservative Seddon. Seddon defended himself against these charges by claiming that Stout was merely bitter about not gaining the leadership.

Women's suffrage

One of the last major campaigns that Stout participated in was the drive to grant voting rights to womenWomen's suffrage

Women's suffrage or woman suffrage is the right of women to vote and to run for office. The expression is also used for the economic and political reform movement aimed at extending these rights to women and without any restrictions or qualifications such as property ownership, payment of tax, or...

. Stout had long been a supporter of this cause, having campaigned tirelessly for his own failed bill in 1878 and Julius Vogel's failed bill in 1887. He had also been highly active in the campaign to increase property rights for women, having been particularly concerned with the right of married women to keep property independently from their husbands.

John Ballance had been a supporter of women's suffrage, although his attempts to pass a bill had been blocked by the conservative Legislative Council

New Zealand Legislative Council

The Legislative Council of New Zealand was the upper house of the New Zealand Parliament from 1853 until 1951. Unlike the lower house, the New Zealand House of Representatives, the Legislative Council was appointed.-Role:...

(the now-abolished upper house of Parliament). Seddon, however, was opposed, and many believed that the cause was now lost. However, a major initiative by suffragette

Suffragette

"Suffragette" is a term coined by the Daily Mail newspaper as a derogatory label for members of the late 19th and early 20th century movement for women's suffrage in the United Kingdom, in particular members of the Women's Social and Political Union...

s led by Kate Sheppard

Kate Sheppard

Katherine Wilson Sheppard Some sources, eg give a birth year of 1847; others eg give a birth year of 1848. was the most prominent member of New Zealand's women's suffrage movement, and is the country's most famous suffragette...

generated considerable support for women's suffrage, and Stout believed that a bill could be passed despite Seddon's objection. A group of progressive politicians, including Stout, successfully passed a women's suffrage bill in 1893 through both the lower and upper houses, with the upper house narrowly passing it after some members who had not been in favour changed their votes because of Seddon's attempts to "kill" the bill in the upper house.

Stout was also involved with the failing Walter Guthrie group of companies in Southland and Otago which had been supported by the Bank of New Zealand

Bank of New Zealand

Bank of New Zealand is one of New Zealand’s largest banks and has been operating continuously in the country since the first office was opened in Auckland in October 1861 followed shortly after by the first branch in Dunedin in December 1861...

, and (according to Bourke) Seddon was prepared to conceal Stout’s involvement – provided Stout left politics.

In 1898 Stout retired from politics. He had represented the seats of Caversham

Caversham (New Zealand electorate)

Caversham was a parliamentary electorate in the city of Dunedin in the Otago Region of New Zealand, from 1866 to 1908.-History:Caversham was first established in 1866 and abolished in 1890. It was recreated in 1893 and abolished again in 1908....

in the 5th parliament

5th New Zealand Parliament

The 5th New Zealand Parliament was a term of the Parliament of New Zealand.Elections for this term were held in 68 European electorates between 14 January and 23 February 1871. Elections in the four Māori electorates were held on 1 and 15 January 1871. A total of 78 MPs were elected. Parliament was...

(1875), Dunedin East

Dunedin East

Dunedin East was a parliamentary electorate in the city of Dunedin in the Otago Region of New Zealand from 1881 to 1890.-History:Dunedin East is one of the electorates that replaced the three-member City of Dunedin electorate. The other two electorate formed in 1881 are Dunedin Central and...

in the 6th parliament

6th New Zealand Parliament

The 6th New Zealand Parliament was a term of the Parliament of New Zealand.Elections for this term were held in 69 European electorates between 20 December 1875 and 29 January 1876. Elections in the four Māori electorates were held on 4 and 15 January 1876. A total of 88 MPs were elected....

(1875–79) and in the 9th parliament

9th New Zealand Parliament

The 9th New Zealand Parliament was a term of the Parliament of New Zealand.Elections for this term were held in 4 Māori electorates and xx general electorates on 21 and 22 July 1884, respectively. A total of 95 MPs were elected. Parliament was prorogued in July 1887...

(1884–87), Inangahua

Inangahua (New Zealand electorate)

Inangahua was a former parliamentary electorate in the Buller District, which is part of the West Coast region of New Zealand, from 1881 to 1896...

in the 11th parliament

11th New Zealand Parliament

The 11th New Zealand Parliament was a term of the Parliament of New Zealand.Elections for this term were held in 4 Māori electorates and 62 European electorates on 27 November and 5 December 1890, respectively...

(1893), and the City of Wellington

Wellington (New Zealand electorate)

Wellington , was a parliamentary electorate in Wellington, New Zealand. It existed from 1853 to 1905 with a break in the 1880s. It was a multi-member electorate. The electorate was represented by 24 Members of Parliament....

in the 12th and 13th parliaments (1893–98).

Life after politics

On 22 June 1899, he was appointed Chief Justice of New ZealandChief Justice of New Zealand

The Chief Justice of New Zealand is the head of the New Zealand judiciary, and presides over the Supreme Court of New Zealand. Before the establishment of the latter court in 2004 the Chief Justice was the presiding judge in the High Court of New Zealand and was also ex officio a member of the...

, and remained in this position until 31 January 1926. As of 2011, Stout was the last Chief Justice of New Zealand to have served in the Parliament of New Zealand

Parliament of New Zealand

The Parliament of New Zealand consists of the Queen of New Zealand and the New Zealand House of Representatives and, until 1951, the New Zealand Legislative Council. The House of Representatives is often referred to as "Parliament".The House of Representatives usually consists of 120 Members of...

.

While Chief Justice, Stout showed a particular interest in the rehabilitation

Rehabilitation (penology)

Rehabilitation means; To restore to useful life, as through therapy and education or To restore to good condition, operation, or capacity....

of criminals, contrasting with the emphasis on punishment

Punishment

Punishment is the authoritative imposition of something negative or unpleasant on a person or animal in response to behavior deemed wrong by an individual or group....

that prevailed at the time. He took a leading part in the consolidation of New Zealand statutes (completed in 1908), and was made a Privy Councillor in 1921. In the same year as his retirement, Stout was appointed to the Legislative Council

New Zealand Legislative Council

The Legislative Council of New Zealand was the upper house of the New Zealand Parliament from 1853 until 1951. Unlike the lower house, the New Zealand House of Representatives, the Legislative Council was appointed.-Role:...

, the last political office he would hold.

Stout also had a role of considerable importance in the development of the New Zealand university system. He had become a member of the Senate of the University of New Zealand

University of New Zealand

The University of New Zealand was the New Zealand university from 1870 to 1961. It was the sole New Zealand university, having a federal structure embracing several constituent colleges at various locations around New Zealand...

in 1885, and remained so until 1930. From 1903 to 1923, he was the university's Chancellor. He was also prominent in Otago University

University of Otago

The University of Otago in Dunedin is New Zealand's oldest university with over 22,000 students enrolled during 2010.The university has New Zealand's highest average research quality and in New Zealand is second only to the University of Auckland in the number of A rated academic researchers it...

from 1891 to 1898, serving on its Council. He played a very significant role in the founding of what is now Victoria University of Wellington

Victoria University of Wellington

Victoria University of Wellington was established in 1897 by Act of Parliament, and was a former constituent college of the University of New Zealand. It is particularly well known for its programmes in law, the humanities, and some scientific disciplines, but offers a broad range of other courses...

– the strong connection between Victoria University and the Stout family is remembered by the university's Stout Research Centre and its Robert Stout Building.

In 1929, Stout became increasingly ill, and never recovered. On 19 July 1930 he died in Wellington. He had been made a K.C.M.G. in 1886.

Works

- The Rise and Progress of New Zealand historical sketch in Musings in Maoriland by Arthur T. Keirle 1890. Digitised by the New Zealand Electronic Text CentreNew Zealand Electronic Text CentreThe New Zealand Electronic Text Centre is a unit of the library at the Victoria University of Wellington which provides a free online archive of New Zealand and Pacific Islands texts and heritage materials. The NZETC has an ongoing programme of digitisation and feature additions to the current...

- Our Railway Gauge in The New Zealand Railways Magazine, Volume 3, Issue 2 (1 June 1928). Digitised by the New Zealand Electronic Text CentreNew Zealand Electronic Text CentreThe New Zealand Electronic Text Centre is a unit of the library at the Victoria University of Wellington which provides a free online archive of New Zealand and Pacific Islands texts and heritage materials. The NZETC has an ongoing programme of digitisation and feature additions to the current...