Panic of 1907

Encyclopedia

Financial crisis

The term financial crisis is applied broadly to a variety of situations in which some financial institutions or assets suddenly lose a large part of their value. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, many financial crises were associated with banking panics, and many recessions coincided with these...

that occurred in the United States when the New York Stock Exchange

New York Stock Exchange

The New York Stock Exchange is a stock exchange located at 11 Wall Street in Lower Manhattan, New York City, USA. It is by far the world's largest stock exchange by market capitalization of its listed companies at 13.39 trillion as of Dec 2010...

fell almost 50% from its peak the previous year. Panic occurred, as this was during a time of economic recession

Recession

In economics, a recession is a business cycle contraction, a general slowdown in economic activity. During recessions, many macroeconomic indicators vary in a similar way...

, and there were numerous runs on banks

Bank run

A bank run occurs when a large number of bank customers withdraw their deposits because they believe the bank is, or might become, insolvent...

and trust companies

Trust company

A trust company is a corporation, especially a commercial bank, organized to perform the fiduciary of trusts and agencies. It is normally owned by one of three types of structures: an independent partnership, a bank, or a law firm, each of which specializes in being a trustee of various kinds of...

. The 1907 panic eventually spread throughout the nation when many state and local banks and businesses entered bankruptcy

Bankruptcy

Bankruptcy is a legal status of an insolvent person or an organisation, that is, one that cannot repay the debts owed to creditors. In most jurisdictions bankruptcy is imposed by a court order, often initiated by the debtor....

. Primary causes of the run include a retraction of market liquidity

Market liquidity

In business, economics or investment, market liquidity is an asset's ability to be sold without causing a significant movement in the price and with minimum loss of value...

by a number of New York City

New York City

New York is the most populous city in the United States and the center of the New York Metropolitan Area, one of the most populous metropolitan areas in the world. New York exerts a significant impact upon global commerce, finance, media, art, fashion, research, technology, education, and...

banks and a loss of confidence among depositors, exacerbated by unregulated side bets at bucket shops.

The crisis was triggered by the failed attempt in October 1907 to corner the market

Cornering the market

In finance, to corner the market is to get sufficient control of a particular stock, commodity, or other asset to allow the price to be manipulated. Another definition: "To have the greatest market share in a particular industry without having a monopoly...

on stock

Stock

The capital stock of a business entity represents the original capital paid into or invested in the business by its founders. It serves as a security for the creditors of a business since it cannot be withdrawn to the detriment of the creditors...

of the United Copper Company

United Copper

The United Copper Company was a short-lived United States copper mining business in the early 20th century that played a pivotal role in the Panic of 1907....

. When this bid failed, banks that had lent money to the cornering scheme suffered runs that later spread to affiliated banks and trusts, leading a week later to the downfall of the Knickerbocker Trust Company

Knickerbocker Trust Company

The Knickerbocker Trust, chartered in 1884 by Frederick G. Eldridge, a friend and classmate of financier J.P. Morgan, figured at one time among the largest banks in the United States and a central player in the Panic of 1907. As a trust company, its main business was serving as trustee for...

—New York City's third-largest trust. The collapse of the Knickerbocker spread fear throughout the city's trusts as regional banks withdrew reserves

Bank reserves

Bank reserves are banks' holdings of deposits in accounts with their central bank , plus currency that is physically held in the bank's vault . The central banks of some nations set minimum reserve requirements...

from New York City banks. Panic extended across the nation as vast numbers of people withdrew deposits from their regional banks.

The panic may have deepened if not for the intervention of financier J. P. Morgan

J. P. Morgan

John Pierpont Morgan was an American financier, banker and art collector who dominated corporate finance and industrial consolidation during his time. In 1892 Morgan arranged the merger of Edison General Electric and Thomson-Houston Electric Company to form General Electric...

, who pledged large sums of his own money, and convinced other New York bankers to do the same, to shore up the banking system

Banking in the United States

Banking in the United States is regulated by both the federal and state governments.The U.S. banking sector's short-term liabilities as of October 11, 2008 are 15% of the gross domestic product of the United States or 43% of its national debt, and the average bank leverage ratio is 12 to...

. At the time, the United States did not have a central bank

Central bank

A central bank, reserve bank, or monetary authority is a public institution that usually issues the currency, regulates the money supply, and controls the interest rates in a country. Central banks often also oversee the commercial banking system of their respective countries...

to inject liquidity back into the market. By November the financial contagion

Financial contagion

Financial contagion refers to a scenario in which small shocks, which initially affect only a few financial institutions or a particular region of an economy, spread to the rest of financial sectors and other countries whose economies were previously healthy, in a manner similar to the transmission...

had largely ended, yet a further crisis emerged when a large brokerage firm borrowed heavily using the stock of Tennessee Coal, Iron and Railroad Company

Tennessee Coal, Iron and Railroad Company

The Tennessee Coal, Iron and Railroad Company , also known as TCI and the Tennessee Company, was a major American steel manufacturer with interests in coal and iron ore mining and railroad operations. Originally based entirely within Tennessee, it relocated most of its business to Alabama in the...

(TC&I) as collateral

Collateral (finance)

In lending agreements, collateral is a borrower's pledge of specific property to a lender, to secure repayment of a loan.The collateral serves as protection for a lender against a borrower's default - that is, any borrower failing to pay the principal and interest under the terms of a loan obligation...

. Collapse of TC&I's stock price was averted by an emergency takeover by Morgan's U.S. Steel Corporation—a move approved by anti-monopolist president Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore "Teddy" Roosevelt was the 26th President of the United States . He is noted for his exuberant personality, range of interests and achievements, and his leadership of the Progressive Movement, as well as his "cowboy" persona and robust masculinity...

. The following year, Senator Nelson W. Aldrich

Nelson W. Aldrich

Nelson Wilmarth Aldrich was a prominent American politician and a leader of the Republican Party in the Senate, where he served from 1881 to 1911....

, father-in-law of John D. Rockefeller, Jr., established and chaired a commission to investigate the crisis and propose future solutions, leading to the creation of the Federal Reserve System

Federal Reserve System

The Federal Reserve System is the central banking system of the United States. It was created on December 23, 1913 with the enactment of the Federal Reserve Act, largely in response to a series of financial panics, particularly a severe panic in 1907...

.

Economic conditions

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

President Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson was the seventh President of the United States . Based in frontier Tennessee, Jackson was a politician and army general who defeated the Creek Indians at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend , and the British at the Battle of New Orleans...

allowed the charter of the Second Bank of the United States

Second Bank of the United States

The Second Bank of the United States was chartered in 1816, five years after the First Bank of the United States lost its own charter. The Second Bank of the United States was initially headquartered in Carpenters' Hall, Philadelphia, the same as the First Bank, and had branches throughout the...

to expire in 1836, the U.S. was without any sort of central bank

Central bank

A central bank, reserve bank, or monetary authority is a public institution that usually issues the currency, regulates the money supply, and controls the interest rates in a country. Central banks often also oversee the commercial banking system of their respective countries...

, and the money supply

Money supply

In economics, the money supply or money stock, is the total amount of money available in an economy at a specific time. There are several ways to define "money," but standard measures usually include currency in circulation and demand deposits .Money supply data are recorded and published, usually...

in New York City fluctuated with the country's annual agricultural cycle. Each autumn money flowed out of the city as harvests were purchased and—in an effort to attract money back—interest rates were raised. Foreign investors then sent their money to New York to take advantage of the higher rates. From the January 1906 Dow Jones Industrial Average

Dow Jones Industrial Average

The Dow Jones Industrial Average , also called the Industrial Average, the Dow Jones, the Dow 30, or simply the Dow, is a stock market index, and one of several indices created by Wall Street Journal editor and Dow Jones & Company co-founder Charles Dow...

high of 103, the market began a modest correction that would continue throughout the year. The April 1906 earthquake

1906 San Francisco earthquake

The San Francisco earthquake of 1906 was a major earthquake that struck San Francisco, California, and the coast of Northern California at 5:12 a.m. on Wednesday, April 18, 1906. The most widely accepted estimate for the magnitude of the earthquake is a moment magnitude of 7.9; however, other...

that devastated San Francisco contributed to the market instability, prompting an even greater flood of money from New York to San Francisco to aid reconstruction. A further stress on the money supply occurred in late 1906, when the Bank of England

Bank of England

The Bank of England is the central bank of the United Kingdom and the model on which most modern central banks have been based. Established in 1694, it is the second oldest central bank in the world...

raised its interest rates, partly in response to UK insurance companies paying out so much to US policyholders, and more funds remained in London than expected. From their peak in January, stock prices declined 18% by July 1906. By late September, stocks had recovered about half of their losses.

Hepburn Act

The Hepburn Act is a 1906 United States federal law that gave the Interstate Commerce Commission the power to set maximum railroad rates. This led to the discontinuation of free passes to loyal shippers. In addition, the ICC could view the railroads' financial records, a task simplified by...

, which gave the Interstate Commerce Commission

Interstate Commerce Commission

The Interstate Commerce Commission was a regulatory body in the United States created by the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887. The agency's original purpose was to regulate railroads to ensure fair rates, to eliminate rate discrimination, and to regulate other aspects of common carriers, including...

(ICC) the power to set maximum railroad rates, became law in July 1906. This depreciated the value of railroad securities. Between September 1906 and March 1907, the stock market slid, losing 7.7% of its capitalization

Market capitalization

Market capitalization is a measurement of the value of the ownership interest that shareholders hold in a business enterprise. It is equal to the share price times the number of shares outstanding of a publicly traded company...

. Between March 9 and 26, stocks fell a further 9.8%. (This March collapse is sometimes referred to as a "rich man's panic".) The economy remained volatile through the summer. A number of shocks hit the system: the stock of Union Pacific—among the most common stocks used as collateral

Collateral (finance)

In lending agreements, collateral is a borrower's pledge of specific property to a lender, to secure repayment of a loan.The collateral serves as protection for a lender against a borrower's default - that is, any borrower failing to pay the principal and interest under the terms of a loan obligation...

—fell 50 points; that June an offering of New York City bonds

Bond (finance)

In finance, a bond is a debt security, in which the authorized issuer owes the holders a debt and, depending on the terms of the bond, is obliged to pay interest to use and/or to repay the principal at a later date, termed maturity...

failed; in July the copper

Copper

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu and atomic number 29. It is a ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. Pure copper is soft and malleable; an exposed surface has a reddish-orange tarnish...

market collapsed; in August the Standard Oil Company was fined $29 million for antitrust

Antitrust

The United States antitrust law is a body of laws that prohibits anti-competitive behavior and unfair business practices. Antitrust laws are intended to encourage competition in the marketplace. These competition laws make illegal certain practices deemed to hurt businesses or consumers or both,...

violations. In the first nine months of 1907, stocks were lower by 24.4%.

On July 27, The Commercial & Financial Chronicle noted that "the market keeps unstable ... no sooner are these signs of new life in evidence than something like a suggestion of a new outflow of gold to Paris sends a tremble all through the list, and the gain in values and hope is gone". Several bank run

Bank run

A bank run occurs when a large number of bank customers withdraw their deposits because they believe the bank is, or might become, insolvent...

s occurred outside the US in 1907: in Egypt in April and May; in Japan in May and June; in Hamburg and Chile in early October. The fall season was always a vulnerable time for the banking system—combined with the roiled stock market, even a small shock could have grave repercussions.

Cornering copper

| Timeline of panic in New York City |

|---|

| Monday, October 14 |

| Otto Heinze begins purchasing to corner the stock of United Copper United Copper The United Copper Company was a short-lived United States copper mining business in the early 20th century that played a pivotal role in the Panic of 1907.... . |

| Wednesday, October 16 |

| Heinze's corner fails spectacularly. Heinze's brokerage house, Gross & Kleeberg is forced to close. This is the date traditionally cited as when the corner failed. |

| Thursday, October 17 |

| The Exchange suspends Otto Heinze and Company. The State Savings Bank of Butte, Montana, owned by Augustus Heinze announces it is insolvent. Augustus is forced to resign from Mercantile National Bank. Runs begin at Augustus' and his associate Charles W. Morse Charles W. Morse Charles Wyman Morse was a notorious businessman and speculator on Wall Street in the early 20th century.-Early life:... 's banks. |

| Sunday, October 20 |

| The New York Clearing House forces Augustus and Morse to resign from all their banking interests. |

| Monday, October 21 |

| Charles T. Barney Charles T. Barney Charles Tracy Barney was the president of the Knickerbocker Trust Company, the collapse of which shortly before Barney's death sparked the Panic of 1907.-Early life and marriage:... is forced to resign from the Knickerbocker Trust Company Knickerbocker Trust Company The Knickerbocker Trust, chartered in 1884 by Frederick G. Eldridge, a friend and classmate of financier J.P. Morgan, figured at one time among the largest banks in the United States and a central player in the Panic of 1907. As a trust company, its main business was serving as trustee for... because of his ties to Morse and Heinze. The National Bank of Commerce says it will no longer serve as clearing house. |

| Tuesday, October 22 |

| A bank run Bank run A bank run occurs when a large number of bank customers withdraw their deposits because they believe the bank is, or might become, insolvent... forces the Knickerbocker to suspend operations. |

| Wednesday, October 23 |

| J.P. Morgan J. P. Morgan John Pierpont Morgan was an American financier, banker and art collector who dominated corporate finance and industrial consolidation during his time. In 1892 Morgan arranged the merger of Edison General Electric and Thomson-Houston Electric Company to form General Electric... persuades other trust company presidents to provide liquidity to the Trust Company of America, staving off its collapse. |

| Thursday, October 24 |

| Treasury Secretary United States Secretary of the Treasury The Secretary of the Treasury of the United States is the head of the United States Department of the Treasury, which is concerned with financial and monetary matters, and, until 2003, also with some issues of national security and defense. This position in the Federal Government of the United... George Cortelyou George B. Cortelyou George Bruce Cortelyou was an American Presidential Cabinet secretary of the early 20th century.-Early life:... agrees to deposit Federal money in New York banks. Morgan persuades bank presidents to provide $23 million to the New York Stock Exchange New York Stock Exchange The New York Stock Exchange is a stock exchange located at 11 Wall Street in Lower Manhattan, New York City, USA. It is by far the world's largest stock exchange by market capitalization of its listed companies at 13.39 trillion as of Dec 2010... to prevent an early closure. |

| Friday October 25 |

| Crisis is again narrowly averted at the Exchange. |

| Sunday, October 27 |

| The City of New York New York City New York is the most populous city in the United States and the center of the New York Metropolitan Area, one of the most populous metropolitan areas in the world. New York exerts a significant impact upon global commerce, finance, media, art, fashion, research, technology, education, and... tells Morgan associate George Perkins that if they cannot raise $20–30 million by November 1, the city will be insolvent. |

| Tuesday, October 29 |

| Morgan purchased $30 million in city bonds, discreetly averting bankruptcy for the city. |

| Saturday, November 2 |

| Moore & Schley, a major brokerage, nears collapse because its loans were backed by the Tennessee Coal, Iron & Railroad Company (TC&I), a stock whose value is uncertain. A proposal is made for U.S. Steel U.S. Steel The United States Steel Corporation , more commonly known as U.S. Steel, is an integrated steel producer with major production operations in the United States, Canada, and Central Europe. The company is the world's tenth largest steel producer ranked by sales... to purchase TC&I. |

| Sunday, November 3 |

| A plan is finalized for U.S. Steel to take over TC&I. |

| Monday, November 4 |

| President Theodore Roosevelt Theodore Roosevelt Theodore "Teddy" Roosevelt was the 26th President of the United States . He is noted for his exuberant personality, range of interests and achievements, and his leadership of the Progressive Movement, as well as his "cowboy" persona and robust masculinity... approves U.S. Steel's takeover of TC&I, despite anticompetitive concerns. |

| Tuesday, November 5 |

| Markets are closed for Election Day Election Day (United States) Election Day in the United States is the day set by law for the general elections of public officials. It occurs on the Tuesday after the first Monday in November. The earliest possible date is November 2 and the latest possible date is November 8... . |

| Wednesday, November 6 |

| U.S. Steel completes takeover of TC&I. Markets begin to recover. Destabilizing runs at the trust companies do not begin again. |

The 1907 panic began with a stock manipulation scheme to corner the market

Cornering the market

In finance, to corner the market is to get sufficient control of a particular stock, commodity, or other asset to allow the price to be manipulated. Another definition: "To have the greatest market share in a particular industry without having a monopoly...

in F. Augustus Heinze

F. Augustus Heinze

Fritz Augustus Heinze was one of the three "Copper Kings" of Butte, Montana, along with William Andrews Clark and Marcus Daly...

's United Copper Company

United Copper

The United Copper Company was a short-lived United States copper mining business in the early 20th century that played a pivotal role in the Panic of 1907....

. Heinze had made a fortune as a copper

Copper

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu and atomic number 29. It is a ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. Pure copper is soft and malleable; an exposed surface has a reddish-orange tarnish...

magnate in Butte, Montana

Butte, Montana

Butte is a city in Montana and the county seat of Silver Bow County, United States. In 1977, the city and county governments consolidated to form the sole entity of Butte-Silver Bow. As of the 2010 census, Butte's population was 34,200...

. In 1906 he moved to New York City, where he formed a close relationship with notorious Wall Street

Wall Street

Wall Street refers to the financial district of New York City, named after and centered on the eight-block-long street running from Broadway to South Street on the East River in Lower Manhattan. Over time, the term has become a metonym for the financial markets of the United States as a whole, or...

banker Charles W. Morse

Charles W. Morse

Charles Wyman Morse was a notorious businessman and speculator on Wall Street in the early 20th century.-Early life:...

. Morse had once successfully cornered New York City's ice market, and together with Heinze gained control of many banks—the pair served on at least six national bank

National bank

In banking, the term national bank carries several meanings:* especially in developing countries, a bank owned by the state* an ordinary private bank which operates nationally...

s, ten state bank

State bank

A state bank is generally a financial institution that is chartered by a state. It differs from a reserve bank in that it does not necessarily control monetary policy , but instead usually offers only retail and commercial services.A state bank that has been in operation for five years or less is...

s, five trust companies and four insurance

Insurance

In law and economics, insurance is a form of risk management primarily used to hedge against the risk of a contingent, uncertain loss. Insurance is defined as the equitable transfer of the risk of a loss, from one entity to another, in exchange for payment. An insurer is a company selling the...

firms.

Share (finance)

A joint stock company divides its capital into units of equal denomination. Each unit is called a share. These units are offered for sale to raise capital. This is termed as issuing shares. A person who buys share/shares of the company is called a shareholder, and by acquiring share or shares in...

had been borrowed

Securities lending

In finance, securities lending or stock lending refers to the lending of securities by one party to another. The terms of the loan will be governed by a "Securities Lending Agreement", which requires that the borrower provides the lender with collateral, in the form of cash, government securities,...

, and sold short, by speculators betting that the stock price would drop, and that they could thus repurchase the borrowed shares cheaply, pocketing the difference. Otto proposed a short squeeze, whereby the Heinzes would aggressively purchase as many remaining shares as possible, and then force the short sellers to pay for their borrowed shares. The aggressive purchasing would drive up the share price, and, being unable to find shares elsewhere, the short sellers would have no option but to turn to the Heinzes, who could then name their price.

To finance the scheme, Otto, Augustus and Charles Morse met with Charles T. Barney

Charles T. Barney

Charles Tracy Barney was the president of the Knickerbocker Trust Company, the collapse of which shortly before Barney's death sparked the Panic of 1907.-Early life and marriage:...

, president of the city's third-largest trust, the Knickerbocker Trust Company

Knickerbocker Trust Company

The Knickerbocker Trust, chartered in 1884 by Frederick G. Eldridge, a friend and classmate of financier J.P. Morgan, figured at one time among the largest banks in the United States and a central player in the Panic of 1907. As a trust company, its main business was serving as trustee for...

. Barney had provided financing for previous Morse schemes. Morse, however, cautioned Otto that he needed much more money than he had to attempt the squeeze and Barney declined to provide funding. Otto decided to attempt the corner anyway. On Monday, October 14, he began aggressively purchasing shares of United Copper, which rose in one day from $39 to $52 per share. On Tuesday, he issued the call for short sellers to return the borrowed stock. The share price rose to nearly $60, but the short sellers were able to find plenty of United Copper shares from sources other than the Heinzes. Otto had misread the market, and the share price of United Copper began to collapse.

The stock closed at $30 on Tuesday and fell to $10 by Wednesday. Otto Heinze was ruined. The stock of United Copper was traded outside the hall of the New York Stock Exchange

New York Stock Exchange

The New York Stock Exchange is a stock exchange located at 11 Wall Street in Lower Manhattan, New York City, USA. It is by far the world's largest stock exchange by market capitalization of its listed companies at 13.39 trillion as of Dec 2010...

, literally an outdoor market "on the curb" (this curb market would later become the American Stock Exchange

American Stock Exchange

NYSE Amex Equities, formerly known as the American Stock Exchange is an American stock exchange situated in New York. AMEX was a mutual organization, owned by its members. Until 1953, it was known as the New York Curb Exchange. On January 17, 2008, NYSE Euronext announced it would acquire the...

). After the crash, The Wall Street Journal

The Wall Street Journal

The Wall Street Journal is an American English-language international daily newspaper. It is published in New York City by Dow Jones & Company, a division of News Corporation, along with the Asian and European editions of the Journal....

reported, "Never has there been such wild scenes on the Curb, so say the oldest veterans of the outside market".

Contagion spreads

The failure of the corner left Otto unable to meet his obligations and sent his brokerage house, Gross & Kleeberg, into bankruptcy. On Thursday, October 17, the New York Stock Exchange suspended Otto's trading privileges. As a result of United Copper's collapse, the State Savings Bank of Butte Montana (owned by F. Augustus Heinze) announced its insolvency. The Montana bank had held United Copper stock as collateralCollateral (finance)

In lending agreements, collateral is a borrower's pledge of specific property to a lender, to secure repayment of a loan.The collateral serves as protection for a lender against a borrower's default - that is, any borrower failing to pay the principal and interest under the terms of a loan obligation...

against some of its lending and had been a correspondent bank for the Mercantile National Bank in New York City, of which F. Augustus Heinze was then president.

F. Augustus Heinze's association with the corner and the insolvent State Savings Bank proved too much for the board of the Mercantile to accept. Although they forced him to resign before lunch time, by then it was too late. As news of the collapse spread, depositors rushed en masse to withdraw money from the Mercantile National Bank. The Mercantile had enough capital to withstand a few days of withdrawals, but depositors began to pull cash from the banks of the Heinzes' associate Charles W. Morse. Runs occurred at Morse's National Bank of North America and the New Amsterdam National. Afraid of the impact the tainted reputations of Augustus Heinze and Morse could have on the banking system, the New York Clearing House

New York Clearing House

The New York Clearing House Association, the nation’s first and largest bank clearing house, was created in 1853, and has played a variety of important roles in supporting the development of the banking system in America’s financial capital. Initially, it was created to simplify the chaotic...

(a consortium of the city's banks) forced Morse and Heinze to resign all banking interests. By the weekend after the failed corner, there was not yet systemic panic. Funds were withdrawn from Heinze-associated banks, only to be deposited with other banks in the city.

Panic hits the trusts

In the early 1900s, trust companiesTrust company

A trust company is a corporation, especially a commercial bank, organized to perform the fiduciary of trusts and agencies. It is normally owned by one of three types of structures: an independent partnership, a bank, or a law firm, each of which specializes in being a trustee of various kinds of...

were booming; in the decade before 1907, their assets had grown by 244%. During the same period, national bank assets grew by 97%, while state banks in New York grew by 82%. The leaders of the high-flying trusts were mainly prominent members of New York's financial and social circles. One of the most respected was Charles T. Barney

Charles T. Barney

Charles Tracy Barney was the president of the Knickerbocker Trust Company, the collapse of which shortly before Barney's death sparked the Panic of 1907.-Early life and marriage:...

, whose late father-in-law William Collins Whitney was a famous financier. Barney's Knickerbocker Trust Company

Knickerbocker Trust Company

The Knickerbocker Trust, chartered in 1884 by Frederick G. Eldridge, a friend and classmate of financier J.P. Morgan, figured at one time among the largest banks in the United States and a central player in the Panic of 1907. As a trust company, its main business was serving as trustee for...

was the third-largest trust in New York.

Clearing house (finance)

A clearing house is a financial institution that provides clearing and settlement services for financial and commodities derivatives and securities transactions...

for the Knickerbocker. On October 22, the Knickerbocker faced a classic bank run. From the bank's opening, the crowd grew. As The New York Times

The New York Times

The New York Times is an American daily newspaper founded and continuously published in New York City since 1851. The New York Times has won 106 Pulitzer Prizes, the most of any news organization...

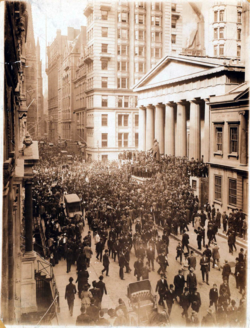

reported, "as fast as a depositor went out of the place ten people and more came asking for their money [and the police] were asked to send some men to keep order". In less than three hours, $8 million was withdrawn from the Knickerbocker. Shortly after noon it was forced to suspend operations.

As news spread, other banks and trust companies were reluctant to lend any money. The interest rates on loans to brokers at the stock exchange soared and, with brokers unable to get money, stock prices fell to a low not seen since December 1900. The panic quickly spread to two other large trusts, Trust Company of America and Lincoln Trust Company. By Thursday, October 24, a chain of failures littered the street: Twelfth Ward Bank, Empire City Savings Bank, Hamilton Bank of New York, First National Bank of Brooklyn, International Trust Company of New York, Williamsburg Trust Company of Brooklyn, Borough Bank of Brooklyn, Jenkins Trust Company of Brooklyn and the Union Trust Company of Providence.

Enter J.P. Morgan

When the chaos began to shake the confidence of New York's banks, the city's most famous banker was out of town. J.P. MorganJ. P. Morgan

John Pierpont Morgan was an American financier, banker and art collector who dominated corporate finance and industrial consolidation during his time. In 1892 Morgan arranged the merger of Edison General Electric and Thomson-Houston Electric Company to form General Electric...

, the eponymous president of J.P. Morgan & Co.

J.P. Morgan & Co.

J.P. Morgan & Co. was a commercial and investment banking institution based in the United States founded by J. Pierpont Morgan and commonly known as the House of Morgan or simply Morgan. Today, J.P...

, was attending a church convention in Richmond, Virginia

Richmond, Virginia

Richmond is the capital of the Commonwealth of Virginia, in the United States. It is an independent city and not part of any county. Richmond is the center of the Richmond Metropolitan Statistical Area and the Greater Richmond area...

. Morgan was not only the city's wealthiest and most well-connected banker, but he had experience with crisis—he helped rescue the U.S. Treasury

United States Department of the Treasury

The Department of the Treasury is an executive department and the treasury of the United States federal government. It was established by an Act of Congress in 1789 to manage government revenue...

during the Panic of 1893

Panic of 1893

The Panic of 1893 was a serious economic depression in the United States that began in 1893. Similar to the Panic of 1873, this panic was marked by the collapse of railroad overbuilding and shaky railroad financing which set off a series of bank failures...

. As news of the crisis gathered, Morgan returned to Wall Street from his convention late on the night of Saturday, October 19. The following morning, the library of Morgan's brownstone

Brownstone

Brownstone is a brown Triassic or Jurassic sandstone which was once a popular building material. The term is also used in the United States to refer to a terraced house clad in this material.-Types:-Apostle Island brownstone:...

at Madison Avenue and 36th St. had become a revolving door of New York City bank and trust company presidents arriving to share information about (and seek help surviving) the impending crisis.

James Stillman

James Jewett Stillman was an American businessman who invested in land, banking, and railroads in New York, Texas, and Mexico.-Biography:...

of the National City Bank of New York (the ancestor of Citibank

Citibank

Citibank, a major international bank, is the consumer banking arm of financial services giant Citigroup. Citibank was founded in 1812 as the City Bank of New York, later First National City Bank of New York...

), and the United States Secretary of the Treasury

United States Secretary of the Treasury

The Secretary of the Treasury of the United States is the head of the United States Department of the Treasury, which is concerned with financial and monetary matters, and, until 2003, also with some issues of national security and defense. This position in the Federal Government of the United...

, George B. Cortelyou

George B. Cortelyou

George Bruce Cortelyou was an American Presidential Cabinet secretary of the early 20th century.-Early life:...

. Cortelyou said that he was ready to deposit government money in the banks to help shore up their deposits. After an overnight audit of the Trust Company of America showed the institution to be sound, on Wednesday afternoon Morgan declared, “This is the place to stop the trouble, then".

As a run began on the Trust Company of America, Morgan worked with Stillman and Baker to liquidate the company's assets to allow the bank to pay depositors. The bank survived to the close of business, but Morgan knew that additional money would be needed to keep it solvent through the following day. That night he assembled the presidents of the other trust companies and held them in a meeting until midnight when they agreed to provide loans of $8.25 million to allow the Trust Company of America to stay open the next day. On Thursday morning Cortelyou deposited around $25 million into a number of New York banks. John D. Rockefeller

John D. Rockefeller

John Davison Rockefeller was an American oil industrialist, investor, and philanthropist. He was the founder of the Standard Oil Company, which dominated the oil industry and was the first great U.S. business trust. Rockefeller revolutionized the petroleum industry and defined the structure of...

, the wealthiest man in America, deposited a further $10 million in Stillman's National City Bank. Rockefeller's massive deposit left the National City Bank with the deepest reserves of any bank in the city. To instill public confidence, Rockefeller phoned Melville Stone, the manager of the Associated Press

Associated Press

The Associated Press is an American news agency. The AP is a cooperative owned by its contributing newspapers, radio and television stations in the United States, which both contribute stories to the AP and use material written by its staff journalists...

, and told him that he would pledge half of his wealth to maintain America's credit.

Stock exchange nears collapse

Despite the infusion of cash, the banks of New York were reluctant to make the short-term loans they typically provided to facilitate daily stock trades. Unable to obtain these funds, prices on the exchange began to crashStock market crash

A stock market crash is a sudden dramatic decline of stock prices across a significant cross-section of a stock market, resulting in a significant loss of paper wealth. Crashes are driven by panic as much as by underlying economic factors...

. At 1:30 p.m. Thursday, October 24, Ransom Thomas, the president of the New York Stock Exchange

New York Stock Exchange

The New York Stock Exchange is a stock exchange located at 11 Wall Street in Lower Manhattan, New York City, USA. It is by far the world's largest stock exchange by market capitalization of its listed companies at 13.39 trillion as of Dec 2010...

, rushed to Morgan's offices to tell him that he would have to close the exchange early. Morgan was emphatic that an early close of the exchange would be catastrophic.

Friday, however, saw more panic on the exchange. Morgan again approached the bank presidents, but this time was only able to convince them to pledge $9.7 million. In order for this money to keep the exchange open, Morgan decided the money could not be used for margin sales

Margin (finance)

In finance, a margin is collateral that the holder of a financial instrument has to deposit to cover some or all of the credit risk of their counterparty...

. The volume of trading on Friday was 2/3 that of Thursday. The markets again narrowly made it to the closing bell.

Crisis of confidence

Morgan, Stillman, Baker and the other city bankers were unable to pool money indefinitely. Even the U.S. Treasury was low on funds. Public confidence needed to be restored, and on Friday evening the bankers formed two committees—one to persuade the clergy to calm their congregations on Sunday, and second to explain to the press the various aspects of the financial rescue package. Europe's most famous banker, Lord RothschildNathan Rothschild, 1st Baron Rothschild

Nathan Mayer Rothschild, 1st Baron Rothschild, Baron de Rothschild was a British banker and politician from the international Rothschild financial dynasty.-Life and family:...

, sent word of his "admiration and respect" for Morgan. In an attempt to gather confidence, the Treasury Secretary Cortelyou agreed that if he returned to Washington it would send a signal to Wall Street that the worst had passed.

|

|

|

|

| (Clockwise from top left) John D. Rockefeller John D. Rockefeller John Davison Rockefeller was an American oil industrialist, investor, and philanthropist. He was the founder of the Standard Oil Company, which dominated the oil industry and was the first great U.S. business trust. Rockefeller revolutionized the petroleum industry and defined the structure of... , George B. Cortelyou George B. Cortelyou George Bruce Cortelyou was an American Presidential Cabinet secretary of the early 20th century.-Early life:... , Lord Rothschild Nathan Rothschild, 1st Baron Rothschild Nathan Mayer Rothschild, 1st Baron Rothschild, Baron de Rothschild was a British banker and politician from the international Rothschild financial dynasty.-Life and family:... , and James Stillman James Stillman James Jewett Stillman was an American businessman who invested in land, banking, and railroads in New York, Texas, and Mexico.-Biography:... . Some of the best-known names on Wall Street issued positive statements to help restore confidence in the economy. |

|

To ensure a free flow of funds on Monday, the New York Clearing House issued $100 million in loan certificates to be traded between banks to settle balances, allowing them to retain cash reserves for depositors. Reassured both by the clergy and the newspapers, and with bank balance sheets flushed with cash, a sense of order returned to New York that Monday.

Unbeknownst to Wall Street, a new crisis was being averted in the background. On Sunday, Morgan's associate, George Perkins, was informed that the City of New York required at least $20 million by November 1 or it would go bankrupt. The city tried to raise money through a standard bond issue, but failed to gather enough financing. On Monday and again on Tuesday, New York Mayor

Mayor of New York City

The Mayor of the City of New York is head of the executive branch of New York City's government. The mayor's office administers all city services, public property, police and fire protection, most public agencies, and enforces all city and state laws within New York City.The budget overseen by the...

George McClellan approached Morgan for assistance. In an effort to avoid the disastrous signal that a New York City bankruptcy would send, Morgan contracted to purchase $30 million worth of city bonds.

Drama at the Library

Although calm was largely restored in New York by Saturday, November 2, yet another crisis loomed. One of the exchange's largest brokerage firms, Moore & Schley, was heavily in debt and in danger of collapse. The firm had borrowed heavily, using stock from the Tennessee Coal, Iron and Railroad CompanyTennessee Coal, Iron and Railroad Company

The Tennessee Coal, Iron and Railroad Company , also known as TCI and the Tennessee Company, was a major American steel manufacturer with interests in coal and iron ore mining and railroad operations. Originally based entirely within Tennessee, it relocated most of its business to Alabama in the...

(TC&I) as collateral. With the value of the thinly-traded stock under pressure, many banks would likely call the loans of Moore & Schley on Monday and force an en masse liquidation of the stock. If that occurred it would send shares of TC&I plummeting, devastating Moore and Schley and causing a further panic in the market.

In order to prevent the collapse of Moore & Schley, Morgan called an emergency conference at his library Saturday morning. A proposal was made that the U.S. Steel Corporation, a company Morgan had helped form through the merger of the steel companies of Andrew Carnegie

Andrew Carnegie

Andrew Carnegie was a Scottish-American industrialist, businessman, and entrepreneur who led the enormous expansion of the American steel industry in the late 19th century...

and Elbert Gary

Elbert Henry Gary

Elbert Henry Gary was an American lawyer, county judge and corporate officer. He was a key founder of U.S. Steel in 1901, bringing together partners J. P. Morgan, Andrew Carnegie, and Charles M. Schwab. The city of Gary, Indiana, a steel town, was named for him when it was founded in 1906...

, would acquire TC&I. This would effectively save Moore & Schley and avert the crisis. After the executives and board of U.S. Steel studied the situation and, recognizing a positive role they could play during the panic, they offered to either loan Moore & Schley $5 million, or buy TC&I for $90 a share. By 7 p.m. an agreement had not been reached and the meeting adjourned.

By then, J.P. Morgan was drawn into another situation. There was a major concern that the Trust Company of America and the Lincoln Trust could fail to open on Monday due to continuing runs. On Saturday evening 40–50 bankers had gathered at the library to discuss the crisis, with the clearing-house bank presidents in the East room and the trust company executives in the West room. Morgan and those dealing with the Moore & Schley situation had moved to the librarian’s office. There Morgan told his counselors that he would agree to help shore up Moore & Schley only if the trust companies would work together to bail out their weakest brethren. The discussion among the bankers continued late Saturday night but without any real progress. Then, around midnight, J.P. Morgan informed a leader of the trust company presidents of the Moore & Schley situation that was going to require $25 million, and that he was not willing to proceed with that unless the problems with the trust companies could also be solved. This indicated that the trust companies would not be receiving further help from Morgan and that they had to reach their own solution.

At 3 a.m. about 120 bank and trust company officials were assembled to hear a full report on the status of the failing trust companies. While the Trust Company of America was barely solvent, the Lincoln Trust Company was probably $1 million short of what it needed to pay depositors. As the discussions continued, the bankers realized that Morgan had locked them in the library and pocketed the key to force a solution, the type of tactic he had been known to use in the past. Morgan then entered the talks and told the trust companies that they must provide a loan of $25 million to save the weaker institutions. The trust presidents were still reluctant to act, but Morgan informed them that if they did not it would result in a complete collapse of the banking system. Through his considerable influence, at about 4:45 a.m. he persuaded the unofficial leader of the trust companies to sign the agreement, and the rest of them followed. With this assurance that the situation would be resolved, Morgan then allowed the bankers to go home.

On Sunday afternoon and into the evening, Morgan, Perkins, Baker and Stillman, along with U.S. Steel's Gary and Henry Clay Frick

Henry Clay Frick

Henry Clay Frick was an American industrialist, financier, and art patron. He founded the H. C. Frick & Company coke manufacturing company, was chairman of the Carnegie Steel Company, and played a major role in the formation of the giant U.S. Steel steel manufacturing concern...

, worked at the library to finalize the deal for U.S. Steel to buy TC&I and by Sunday night had a plan for acquisition. But, one obstacle remained: the anti-trust crusading President Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore "Teddy" Roosevelt was the 26th President of the United States . He is noted for his exuberant personality, range of interests and achievements, and his leadership of the Progressive Movement, as well as his "cowboy" persona and robust masculinity...

, who had made breaking up monopolies

Monopoly

A monopoly exists when a specific person or enterprise is the only supplier of a particular commodity...

a focus of his presidency.

Frick and Gary traveled overnight by train to the White House

White House

The White House is the official residence and principal workplace of the president of the United States. Located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., the house was designed by Irish-born James Hoban, and built between 1792 and 1800 of white-painted Aquia sandstone in the Neoclassical...

to implore Roosevelt to set aside the principles of the Sherman Antitrust Act

Sherman Antitrust Act

The Sherman Antitrust Act requires the United States federal government to investigate and pursue trusts, companies, and organizations suspected of violating the Act. It was the first Federal statute to limit cartels and monopolies, and today still forms the basis for most antitrust litigation by...

and allow—before the market opened—a company that already had a 60% market share to make a massive acquisition. Roosevelt's secretary refused to see them, yet Frick and Gary convinced James Rudolph Garfield

James Rudolph Garfield

James Rudolph Garfield was an American politician, lawyer and son of President James Abram Garfield and First Lady Lucretia Garfield. He was Secretary of the Interior during Theodore Roosevelt's administration....

, the Secretary of the Interior

United States Secretary of the Interior

The United States Secretary of the Interior is the head of the United States Department of the Interior.The US Department of the Interior should not be confused with the concept of Ministries of the Interior as used in other countries...

, to bypass the secretary and allow them to go directly to the president. With less than an hour before markets opened, Roosevelt and Secretary of State

United States Secretary of State

The United States Secretary of State is the head of the United States Department of State, concerned with foreign affairs. The Secretary is a member of the Cabinet and the highest-ranking cabinet secretary both in line of succession and order of precedence...

Elihu Root

Elihu Root

Elihu Root was an American lawyer and statesman and the 1912 recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize. He was the prototype of the 20th century "wise man", who shuttled between high-level government positions in Washington, D.C...

began to review the proposed takeover and absorb the news of a potential crash if the merger was not approved. Roosevelt relented, and he later recalled of the meeting, "It was necessary for me to decide on the instant before the Stock Exchange opened, for the situation in New York was such that any hour might be vital. I do not believe that anyone could justly criticize me for saying that I would not feel like objecting to the purchase under those circumstances". When news reached New York, confidence soared. The Commercial & Financial Chronicle

Commercial & Financial Chronicle

The Commercial & Financial Chronicle was a business newspaper in the United States founded by William Buck Dana in 1865. Published weekly, the Commercial & Financial Chronicle was deliberately modeled to be an American take on the popular business newspaper The Economist, which had been founded...

reported that "the relief furnished by this transaction was instant and far-reaching". The final crisis of the panic had been averted.

Aftermath

The panic of 1907 occurred during a lengthy economic contraction—measured by the National Bureau of Economic ResearchNational Bureau of Economic Research

The National Bureau of Economic Research is an American private nonprofit research organization "committed to undertaking and disseminating unbiased economic research among public policymakers, business professionals, and the academic community." The NBER is well known for providing start and end...

as occurring between May 1907 and June 1908. The interrelated contraction, bank panic and falling stock market resulted in significant economic disruption. Industrial production dropped further than after any previous bank run, while 1907 saw the second-highest volume of bankruptcies to that date. Production fell by 11%, imports by 26%, while unemployment rose to 8% from under 3%. Immigration dropped to 750,000 people in 1909, from 1.2 million two years earlier.

Since the end of the Civil War

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

, the United States had experienced panics of varying severity. Economists Charles Calomiris and Gary Gorton rate the worst panics as those leading to widespread bank suspensions—the panics of 1873

Panic of 1873

The Panic of 1873 triggered a severe international economic depression in both Europe and the United States that lasted until 1879, and even longer in some countries. The depression was known as the Great Depression until the 1930s, but is now known as the Long Depression...

, 1893

Panic of 1893

The Panic of 1893 was a serious economic depression in the United States that began in 1893. Similar to the Panic of 1873, this panic was marked by the collapse of railroad overbuilding and shaky railroad financing which set off a series of bank failures...

, and 1907, and a suspension in 1914. Widespread suspensions were forestalled through coordinated actions during both the 1884

Panic of 1884

The Panic of 1884 was a panic during the Recession of 1882-85. Gold reserves of Europe were depleted and the New York City national banks, with tacit approval of the United States Treasury Department, halted investments in the rest of the United States and called in outstanding loans. A larger...

and the 1890

Panic of 1890

The Panic of 1890 was an acute depression, although less serious than other panics of the era. It was precipitated by the near insolvency of Barings Bank in London. Barings, led by Edward Baring, 1st Baron Revelstoke, faced bankruptcy in November 1890 due mainly to excessive risk-taking on poor...

panics. A bank crisis in 1896

Panic of 1896

The Panic of 1896 was an acute economic depression in the United States that was less serious than other panics of the era precipitated by a drop in silver reserves and market concerns on the effects it would have on the gold standard. Deflation of commodities prices drove the stock market to new...

, in which there was a perceived need for coordination, is also sometimes classified as a panic.

The frequency of crises and the severity of the 1907 panic added to concern about the outsized role of J.P. Morgan which led to renewed impetus toward a national debate on reform. In May 1908, Congress passed the Aldrich–Vreeland Act

Aldrich-Vreeland Act

The Aldrich–Vreeland Act was passed in response to the Panic of 1907 and established the National Monetary Commission, which recommended the Federal Reserve Act of 1913....

that established the National Monetary Commission

National Monetary Commission

National Monetary Commission was a study group created by the Aldrich Vreeland Act of 1908. After the Panic of 1907 American bankers turned to Europe for ideas on how to operate a central bank. Senator Nelson Aldrich, Republican leader of the Senate, personally led a team of experts to major...

to investigate the panic and to propose legislation to regulate banking. Senator Nelson Aldrich (R

Republican Party (United States)

The Republican Party is one of the two major contemporary political parties in the United States, along with the Democratic Party. Founded by anti-slavery expansion activists in 1854, it is often called the GOP . The party's platform generally reflects American conservatism in the U.S...

–RI

Rhode Island

The state of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, more commonly referred to as Rhode Island , is a state in the New England region of the United States. It is the smallest U.S. state by area...

), the chairman of the National Monetary Commission, went to Europe for almost two years to study that continent's banking systems.

Central bank

A significant difference between the European and U.S. banking systems was the absence of a central bankCentral bank

A central bank, reserve bank, or monetary authority is a public institution that usually issues the currency, regulates the money supply, and controls the interest rates in a country. Central banks often also oversee the commercial banking system of their respective countries...

in the United States. European states were able to extend the supply of money

Money supply

In economics, the money supply or money stock, is the total amount of money available in an economy at a specific time. There are several ways to define "money," but standard measures usually include currency in circulation and demand deposits .Money supply data are recorded and published, usually...

during periods of low cash reserves. The belief that the U.S. economy was vulnerable without a central bank was not new. Early in 1907, banker Jacob Schiff

Jacob Schiff

Jacob Henry Schiff, born Jakob Heinrich Schiff was a German-born Jewish American banker and philanthropist, who helped finance, among many other things, the Japanese military efforts against Tsarist Russia in the Russo-Japanese War.From his base on Wall Street, he was the foremost Jewish leader...

of Kuhn, Loeb & Co.

Kuhn, Loeb & Co.

Kuhn, Loeb & Co. was a bulge bracket, investment bank founded in 1867 by Abraham Kuhn and Solomon Loeb. Under the leadership of Jacob H. Schiff, it grew to be one of the most influential investment banks in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, financing America's expanding railways and growth...

warned in a speech to the New York Chamber of Commerce that "unless we have a central bank with adequate control of credit resources, this country is going to undergo the most severe and far reaching money panic in its history".

Aldrich convened a secret conference with a number of the nation's leading financiers at the Jekyll Island Club

Jekyll Island Club

The Jekyll Island Club was a private club located on Jekyll Island, on the Georgia coastline. It was founded in 1886 when members of an incorporated hunting and recreational club purchased the island for $125,000 from John Eugune du Bignon. The original design of the Jekyll Island Clubhouse, with...

, off the coast of Georgia

Georgia (U.S. state)

Georgia is a state located in the southeastern United States. It was established in 1732, the last of the original Thirteen Colonies. The state is named after King George II of Great Britain. Georgia was the fourth state to ratify the United States Constitution, on January 2, 1788...

, to discuss monetary policy and the banking system in November 1910. Aldrich and A. P. Andrew

Abram Andrew

Abram Piatt Andrew Jr. was a United States Representative from Massachusetts.-Biography:Born in La Porte, Indiana, he attended the public schools and the Lawrenceville School...

(Assistant Secretary of the Treasury Department), Paul Warburg

Paul Warburg

Paul Moritz Warburg was a German-born American banker and early advocate of the U.S. Federal Reserve system.- Early life :...

(representing Kuhn, Loeb & Co.), Frank A. Vanderlip

Frank A. Vanderlip

Frank A. Vanderlip was an American banker. From 1897-1901, Vanderlip was the Assistant Secretary of Treasury for President of the United States William McKinley's second term. In that office he negotiated with National City Bank a $200 million loan to the government to finance the Spanish...

(James Stillman's successor as president of the National City Bank of New York), Henry P. Davison

Henry P. Davison

Henry Pomeroy Davison, Sr. was an American banker and philanthropist.-Biography:He was born on June 12, 1867 in Troy, Pennsylvania, the oldest of the four children of Henrietta and George B. Davison. Henry's mother died when he was just eight years old in 1875...

(senior partner of J. P. Morgan Company), Charles D. Norton (president of the Morgan-dominated First National Bank of New York), and Benjamin Strong (representing J. P. Morgan), produced a design for a "National Reserve Bank".

Forbes

Forbes

Forbes is an American publishing and media company. Its flagship publication, the Forbes magazine, is published biweekly. Its primary competitors in the national business magazine category are Fortune, which is also published biweekly, and Business Week...

magazine founder B. C. Forbes

B. C. Forbes

Bertie Charles Forbes was a Scottish financial journalist and author who founded Forbes Magazine.-Life and career:He was born in New Deer, Aberdeenshire, in Scotland...

wrote several years later:

Picture a party of the nation’s greatest bankers stealing out of New York on a private railroad car under cover of darkness, stealthily riding hundreds of miles South, embarking on a mysterious launch, sneaking onto an island deserted by all but a few servants, living there a full week under such rigid secrecy that the names of not one of them was once mentioned, lest the servants learn the identity and disclose to the world this strangest, most secret expedition in the history of American finance. I am not romancing; I am giving to the world, for the first time, the real story of how the famous Aldrich currency report, the foundation of our new currency system, was written.

The final report of the National Monetary Commission was published on January 11, 1911. For nearly two years legislators debated the proposal and it was not until December 23, 1913, that Congress passed the Federal Reserve Act

Federal Reserve Act

The Federal Reserve Act is an Act of Congress that created and set up the Federal Reserve System, the central banking system of the United States of America, and granted it the legal authority to issue Federal Reserve Notes and Federal Reserve Bank Notes as legal tender...

. President Woodrow Wilson

Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson was the 28th President of the United States, from 1913 to 1921. A leader of the Progressive Movement, he served as President of Princeton University from 1902 to 1910, and then as the Governor of New Jersey from 1911 to 1913...

signed the legislation immediately and the legislation was enacted on the same day, December 23, 1913, creating the Federal Reserve System

Federal Reserve System

The Federal Reserve System is the central banking system of the United States. It was created on December 23, 1913 with the enactment of the Federal Reserve Act, largely in response to a series of financial panics, particularly a severe panic in 1907...

. Charles Hamlin

Charles Hamlin

Charles Sumner Hamlin was an American lawyer and the first Chairman of the Federal Reserve.He was born in Boston, Massachusetts on August 30, 1861, and graduated from Harvard University in 1886. From 1893 to 1897 and again from 1913 to 1914 he was the Assistant Secretary of the Treasury. He twice...

became the Fed's first chairman, and none other than Morgan's deputy Benjamin Strong became president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York

Federal Reserve Bank of New York

The Federal Reserve Bank of New York is one of the 12 Federal Reserve Banks of the United States. It is located at 33 Liberty Street, New York, NY. It is responsible for the Second District of the Federal Reserve System, which encompasses New York state, the 12 northern counties of New Jersey,...

, the most important regional bank with a permanent seat on the Federal Open Market Committee

Federal Open Market Committee

The Federal Open Market Committee , a committee within the Federal Reserve System, is charged under United States law with overseeing the nation's open market operations . It is the Federal Reserve committee that makes key decisions about interest rates and the growth of the United States money...

.

Pujo Committee

Plutocracy

Plutocracy is rule by the wealthy, or power provided by wealth. The combination of both plutocracy and oligarchy is called plutarchy. The word plutocracy is derived from the Ancient Greek root ploutos, meaning wealth and kratos, meaning to rule or to govern.-Usage:The term plutocracy is generally...

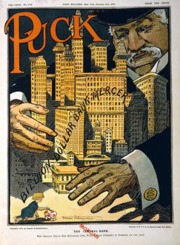

and concentrated wealth soon eroded this view. Morgan's bank had survived, but the trust companies that were a growing rival to traditional banks were badly damaged. Some analysts believed that the panic had been engineered to damage confidence in trust companies so that banks would benefit. Others believed Morgan took advantage of the panic to allow his U.S. Steel company to acquire TC&I. Although Morgan lost $21 million in the panic, and the significance of the role he played in staving off worse disaster is undisputed, he also became the focus of intense scrutiny and criticism.

The chair of the House Committee on Banking and Currency, Representative Arsène Pujo

Arsène Pujo

Arsène Paulin Pujo , was a member of the United States House of Representatives best known for chairing the "Pujo Committee", which sought to expose an anticompetitive conspiracy among some of the nation's most powerful financial interests.-Biography:Pujo practiced law in Louisiana, and was elected...

, (D

Democratic Party (United States)

The Democratic Party is one of two major contemporary political parties in the United States, along with the Republican Party. The party's socially liberal and progressive platform is largely considered center-left in the U.S. political spectrum. The party has the lengthiest record of continuous...

–La.

Louisiana

Louisiana is a state located in the southern region of the United States of America. Its capital is Baton Rouge and largest city is New Orleans. Louisiana is the only state in the U.S. with political subdivisions termed parishes, which are local governments equivalent to counties...

7th

Louisiana's 7th congressional district

Louisiana's 7th congressional district is a congressional district in the U.S. state of Louisiana located in the southwestern part of the state. It contains the cities of Crowley, Eunice, Jennings, Lafayette, Lake Charles, Opelousas, Sulphur and Ville Platte....

) convened a special committee to investigate a "money trust", the de facto monopoly of Morgan and New York's other most powerful bankers. The committee issued a scathing report on the banking trade, and found that the officers of J.P. Morgan & Co.

J.P. Morgan & Co.

J.P. Morgan & Co. was a commercial and investment banking institution based in the United States founded by J. Pierpont Morgan and commonly known as the House of Morgan or simply Morgan. Today, J.P...

also sat on the boards of directors of 112 corporations with a market capitalization of $22.5 billion (the total capitalization of the New York Stock Exchange

New York Stock Exchange

The New York Stock Exchange is a stock exchange located at 11 Wall Street in Lower Manhattan, New York City, USA. It is by far the world's largest stock exchange by market capitalization of its listed companies at 13.39 trillion as of Dec 2010...

was then estimated at $26.5 billion).

Although suffering ill health, J.P. Morgan testified before the Pujo Committee and faced several days of questioning from Samuel Untermyer

Samuel Untermyer

Samuel Untermyer Samuel Untermyer Samuel Untermyer (March 6, 1858 – March 16, 1940, although some sources cite March 2, 1858, and even others, June 6, 1858 also known as Samuel Untermeyer was a Jewish-American lawyer and civic leader as well as a self-made millionaire. He was born in...

. Untermyer and Morgan's famous exchange on the fundamentally psychological nature of banking—that it is an industry built on trust—is often quoted in business articles:

- Untermyer: Is not commercial credit based primarily upon money or property?

- Morgan: No, sir. The first thing is character.

- Untermyer: Before money or property?

- Morgan: Before money or anything else. Money cannot buy it ... a man I do not trust could not get money from me on all the bonds in Christendom.

Associates of Morgan blamed his continued physical decline on the hearings. In February he became very ill and died on March 31, 1913—nine months before the "money trust" would be officially replaced as lender of last resort by the Federal Reserve.

In fiction

In October 1912, Owen JohnsonOwen Johnson

Owen McMahon Johnson was an American writer best remembered for his stories and novels cataloguing the educational and personal growth of the fictional character Dink Stover....

commenced a serial novel about the Panic in McClure's

McClure's

McClure's or McClure's Magazine was an American illustrated monthly periodical popular at the turn of the 20th century. The magazine is credited with creating muckraking journalism. Ida Tarbell's series in 1902 exposing the monopoly abuses of John D...

, entitled the Sixty-first Second. McClure's published many of the works of the muckrakers and other progressives

Progressivism in the United States

Progressivism in the United States is a broadly based reform movement that reached its height early in the 20th century and is generally considered to be middle class and reformist in nature. It arose as a response to the vast changes brought by modernization, such as the growth of large...

, and Johnson's novel mirrors many of the criticisms that the progressives expressed concerning the Panic

Panic

Panic is a sudden sensation of fear which is so strong as to dominate or prevent reason and logical thinking, replacing it with overwhelming feelings of anxiety and frantic agitation consistent with an animalistic fight-or-flight reaction...

and the Money Trust

Money Trust

The main belief behind the concept of a money trust is that control of the majority of the world's financial wealth and political power could be controlled by a powerful few.-Pujo Committee:...

in general. J. P. Morgan appears under the name of "Gunther." The scene at the Morgan Library, which is quite effectively drawn, is in Chapter XVIII. The novel was republished in book form by Frederick A. Stokes

Frederick A. Stokes

Frederick A. Stokes was an eponymous American publishing company. Stokes was a graduate of Yale Law School. He had previously worked for Dodd, Mead and Company and then briefly had partnerships with others before founding his company in 1890....

in 1913.

More recently, the Panic of 1907 has been described in the central chapters of Richard Mason

Richard Mason

Richard Mason may refer to:* Richard Mason , English author of The World of Suzie Wong* Richard Mason , English writer, the author of The Drowning People* Richard Mason Richard Mason may refer to:* Richard Mason (novelist 1919–1997), English author of The World of Suzie Wong* Richard Mason...

's History of a Pleasure Seeker (2011).

See also

- Mercantile National Bank BuildingMercantile National Bank BuildingThe Mercantile National Bank Building is the former home of the Mercantile National Bank, later MCorp Bank, located at 1700 Main Street in downtown Dallas, Texas . It is a contributing structure in the Main Street District. The design of the skyscraper features Moderne styling from the Art Deco...

- A Central Bank as a Menace to Liberty, by George H. Earle, Jr.—Philadelphia lawyer and businessman. (1908)