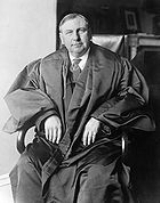

Harlan Fiske Stone

Encyclopedia

Harlan Fiske Stone was an American

lawyer

and jurist

. A native of New Hampshire

, he served as the dean of Columbia Law School

, his alma mater

, in the early 20th century. As a member of the Republican Party

, he was appointed as the 52nd Attorney General of the United States

before becoming an Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court

in 1925. In 1941, Stone became the 12th Chief Justice

of the court, serving until his death in 1946 – one of the shortest terms of any Chief Justice. Stone was the first Chief Justice not to have served in elected office.

Stone was born in Chesterfield

Stone was born in Chesterfield

, New Hampshire

, to Fred L. and Ann S. (Butler) Stone. He prepared at Amherst

High School, and graduated Phi Beta Kappa from Amherst College

in 1894.

From 1894 to 1895 he was the submaster of Newburyport High School

. From 1895 to 1896 he was an instructor in history at Adelphi Academy

in Brooklyn, New York. He also received his M.A.

from Amherst College in 1897.

from 1895 to 1898, received an LL.B., and was admitted to the New York bar in 1898. Stone practiced law in New York City

, initially as a member of the firm Satterlee, Sullivan & Stone, and later as a partner in the firm Sullivan & Cromwell

. From 1899 to 1902 he lectured on law at Columbia Law School. He was a professor there from 1902 to 1905 and eventually served as the school's dean from 1910 to 1923. He lived in The Colosseum

, an apartment building near campus.

During World War I

, Stone served for several months on a War Department

Board of Inquiry, with Major Walter Kellogg of the U.S. Army Judge Advocate Corps and Judge Julian Mack

, that reviewed the cases of 2,294 men whose requests for conscientious objector status had been denied by their draft boards. The Board was charged with determining the sincerity of each man's principles, but often devoted only a few minutes to interrogation and rendering a decision. Stone was impatient with men who took advantage of the benefits of life in America–using postage stamps was his example–without accepting the burdens of citizenship. In a majority of cases, the Board's subjects either relinquished their claims or were judged insincere. He later summarized his experience with little sympathy: "The great mass of our citizens subordinated their individual conscience and their opinions to the good of the common cause" while "there was a residue whose peculiar beliefs...refused to yield to the opinions of others or to force." Nevertheless, he recognized the courage required to persist as a conscientious objector: "The Army was not a bed of roses for the conscientious objector; and the normal man who was not supported in his stand by profound moral conviction might well have chosen active duty at the front as the easier lot."

At the end of the war, he criticized Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer

for his attempts to deport aliens based on administrative action without allowing for any judicial review of their cases.

In 1924, he was appointed United States Attorney General

by his Amherst classmate President

Calvin Coolidge

. As Attorney General, Stone was responsible for the appointment of J. Edgar Hoover

as head of the Department of Justice's

Bureau of Investigation, which later became the Federal Bureau of Investigation

(FBI).

, becoming Coolidge's only appointment to the Court. He was confirmed by the United States Senate

on February 5 and received his commission the same day.

During the 1932–1937 Supreme Court terms, Stone and his colleagues Justices Brandeis

and Cardozo

were considered the Three Musketeers of the Supreme Court, its liberal faction. The three were highly supportive of President Roosevelt's

New Deal

programs, which many other Supreme Court Justices opposed. For example, he wrote for the court in United States v. Darby Lumber Co.

, , which upheld challenged provisions of the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938. Stone also authored the Court's opinion in United States v. Carolene Products Co.

, , which, in its famous "Footnote 4," provided a roadmap for judicial review in the post-Lochner v. New York

era.

Stone's support of the New Deal brought him Roosevelt's favor, and on June 12, 1941, the President elevated him to Chief Justice, a position vacated by Charles Evans Hughes

. Stone was confirmed by the United States Senate on June 27 and received his commission on July 3. He remained in this position for the rest of his life.

soil by military tribunals in Ex parte Quirin

, . The court's handling of this case has been the subject of scrutiny and controversy.

Stone also wrote one of the major opinions in establishing the standard for state

courts to have personal jurisdiction over litigants in International Shoe Co. v. Washington

, .

As Chief Justice, Stone described the Nuremberg court

as "a fraud" to Germans.

He opposed overturning precedents that would have barred a Seventh-day Adventist

from being naturalized as a U.S. citizen if he refused to take up military arms during wartime despite being willing to serve as a conscientious objector

.

Stone was the fourth Chief Justice to have previously served as an Associate Justice and the second to have served in both positions consecutively. To date, Justice Stone is the only justice to have occupied all nine seniority positions on the bench, having moved from most junior Associate Justice to most senior Associate Justice and then to Chief Justice.

In 1946, at the age of 73, Stone died of a cerebral hemorrhage that struck while Justice Douglas

was reading the majority opinion in Girouard v. United States

from the bench; Stone had planned to read his dissent afterwards. He is the only Supreme Court Justice to have died during an open court session.

, and a member of the American Bar Association

.

He was awarded an honorary master of arts

degree from Amherst College

in 1900, and an honorary Doctor of Laws degree from Amherst in 1913. Yale

awarded him an honorary doctor of laws degree in 1924. Columbia and Williams

each awarded him the same honorary degree in 1925.

Stone married Agnes E. Harvey in 1899. Their children were Lauson H. Stone

and the mathematician Marshall H. Stone

. Stone is buried at Rock Creek Cemetery

in the Petworth

neighborhood of Washington, D.C.

His burial is said to be "quite neighborly with other Justices even after death." Four justices buried in Rock Creek "are essentially paired off." Justice Willis Van Devanter

is in a family plot within 40 yards of the senior John Marshall Harlan

. Chief Justice and Mrs. Harlan Fiske Stone have a "handsome memorial" within 25 yards of Stephen Johnson Field

's "imposing black obelisk

".

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

lawyer

Lawyer

A lawyer, according to Black's Law Dictionary, is "a person learned in the law; as an attorney, counsel or solicitor; a person who is practicing law." Law is the system of rules of conduct established by the sovereign government of a society to correct wrongs, maintain the stability of political...

and jurist

Judge

A judge is a person who presides over court proceedings, either alone or as part of a panel of judges. The powers, functions, method of appointment, discipline, and training of judges vary widely across different jurisdictions. The judge is supposed to conduct the trial impartially and in an open...

. A native of New Hampshire

New Hampshire

New Hampshire is a state in the New England region of the northeastern United States of America. The state was named after the southern English county of Hampshire. It is bordered by Massachusetts to the south, Vermont to the west, Maine and the Atlantic Ocean to the east, and the Canadian...

, he served as the dean of Columbia Law School

Columbia Law School

Columbia Law School, founded in 1858, is one of the oldest and most prestigious law schools in the United States. A member of the Ivy League, Columbia Law School is one of the professional graduate schools of Columbia University in New York City. It offers the J.D., LL.M., and J.S.D. degrees in...

, his alma mater

Alma mater

Alma mater , pronounced ), was used in ancient Rome as a title for various mother goddesses, especially Ceres or Cybele, and in Christianity for the Virgin Mary.-General term:...

, in the early 20th century. As a member of the Republican Party

Republican Party (United States)

The Republican Party is one of the two major contemporary political parties in the United States, along with the Democratic Party. Founded by anti-slavery expansion activists in 1854, it is often called the GOP . The party's platform generally reflects American conservatism in the U.S...

, he was appointed as the 52nd Attorney General of the United States

United States Attorney General

The United States Attorney General is the head of the United States Department of Justice concerned with legal affairs and is the chief law enforcement officer of the United States government. The attorney general is considered to be the chief lawyer of the U.S. government...

before becoming an Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court

Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States is the highest court in the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all state and federal courts, and original jurisdiction over a small range of cases...

in 1925. In 1941, Stone became the 12th Chief Justice

Chief Justice of the United States

The Chief Justice of the United States is the head of the United States federal court system and the chief judge of the Supreme Court of the United States. The Chief Justice is one of nine Supreme Court justices; the other eight are the Associate Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States...

of the court, serving until his death in 1946 – one of the shortest terms of any Chief Justice. Stone was the first Chief Justice not to have served in elected office.

Early years

Chesterfield, New Hampshire

Chesterfield is a town in Cheshire County, New Hampshire, United States. The population was 3,604 at the 2010 census. It includes the village of Spofford...

, New Hampshire

New Hampshire

New Hampshire is a state in the New England region of the northeastern United States of America. The state was named after the southern English county of Hampshire. It is bordered by Massachusetts to the south, Vermont to the west, Maine and the Atlantic Ocean to the east, and the Canadian...

, to Fred L. and Ann S. (Butler) Stone. He prepared at Amherst

Amherst, Massachusetts

Amherst is a town in Hampshire County, Massachusetts, United States in the Connecticut River valley. As of the 2010 census, the population was 37,819, making it the largest community in Hampshire County . The town is home to Amherst College, Hampshire College, and the University of Massachusetts...

High School, and graduated Phi Beta Kappa from Amherst College

Amherst College

Amherst College is a private liberal arts college located in Amherst, Massachusetts, United States. Amherst is an exclusively undergraduate four-year institution and enrolled 1,744 students in the fall of 2009...

in 1894.

From 1894 to 1895 he was the submaster of Newburyport High School

Newburyport High School

Newburyport High School is a public high school serving students in ninth through twelfth grades in Newburyport, Massachusetts and is part of the Newburyport Public School System...

. From 1895 to 1896 he was an instructor in history at Adelphi Academy

Adelphi University

Adelphi University is a private, nonsectarian university located in Garden City, in Nassau County, New York, United States. It is the oldest institution of higher education on Long Island. For the sixth year, Adelphi University has been named a “Best Buy” in higher education by the Fiske Guide to...

in Brooklyn, New York. He also received his M.A.

Master of Arts (postgraduate)

A Master of Arts from the Latin Magister Artium, is a type of Master's degree awarded by universities in many countries. The M.A. is usually contrasted with the M.S. or M.Sc. degrees...

from Amherst College in 1897.

Legal career

Stone attended Columbia Law SchoolColumbia Law School

Columbia Law School, founded in 1858, is one of the oldest and most prestigious law schools in the United States. A member of the Ivy League, Columbia Law School is one of the professional graduate schools of Columbia University in New York City. It offers the J.D., LL.M., and J.S.D. degrees in...

from 1895 to 1898, received an LL.B., and was admitted to the New York bar in 1898. Stone practiced law in New York City

New York City

New York is the most populous city in the United States and the center of the New York Metropolitan Area, one of the most populous metropolitan areas in the world. New York exerts a significant impact upon global commerce, finance, media, art, fashion, research, technology, education, and...

, initially as a member of the firm Satterlee, Sullivan & Stone, and later as a partner in the firm Sullivan & Cromwell

Sullivan & Cromwell

Sullivan & Cromwell LLP is an international law firm headquartered in New York. The firm has approximately 800 lawyers in 12 offices, located in financial centers in the United States, Asia, Australia and Europe. Sullivan & Cromwell was founded by Algernon Sydney Sullivan and William Nelson...

. From 1899 to 1902 he lectured on law at Columbia Law School. He was a professor there from 1902 to 1905 and eventually served as the school's dean from 1910 to 1923. He lived in The Colosseum

The Colosseum (apartment building)

The Colosseum is a Manhattan apartment building located at 116th Street and Riverside Drive.The building is noted for its curved façade and impressive marble lobby. Across 116th Street, The Colosseum faces The Paterno, another building with a similar curved facade...

, an apartment building near campus.

During World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

, Stone served for several months on a War Department

United States Department of War

The United States Department of War, also called the War Department , was the United States Cabinet department originally responsible for the operation and maintenance of the United States Army...

Board of Inquiry, with Major Walter Kellogg of the U.S. Army Judge Advocate Corps and Judge Julian Mack

Julian Mack

Julian William Mack was a United States federal judge and social reformer.-Early life and education:...

, that reviewed the cases of 2,294 men whose requests for conscientious objector status had been denied by their draft boards. The Board was charged with determining the sincerity of each man's principles, but often devoted only a few minutes to interrogation and rendering a decision. Stone was impatient with men who took advantage of the benefits of life in America–using postage stamps was his example–without accepting the burdens of citizenship. In a majority of cases, the Board's subjects either relinquished their claims or were judged insincere. He later summarized his experience with little sympathy: "The great mass of our citizens subordinated their individual conscience and their opinions to the good of the common cause" while "there was a residue whose peculiar beliefs...refused to yield to the opinions of others or to force." Nevertheless, he recognized the courage required to persist as a conscientious objector: "The Army was not a bed of roses for the conscientious objector; and the normal man who was not supported in his stand by profound moral conviction might well have chosen active duty at the front as the easier lot."

At the end of the war, he criticized Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer

Alexander Mitchell Palmer

Alexander Mitchell Palmer was Attorney General of the United States from 1919 to 1921. He was nicknamed The Fighting Quaker and he directed the controversial Palmer Raids.-Congressional career:...

for his attempts to deport aliens based on administrative action without allowing for any judicial review of their cases.

In 1924, he was appointed United States Attorney General

United States Attorney General

The United States Attorney General is the head of the United States Department of Justice concerned with legal affairs and is the chief law enforcement officer of the United States government. The attorney general is considered to be the chief lawyer of the U.S. government...

by his Amherst classmate President

President of the United States

The President of the United States of America is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president leads the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces....

Calvin Coolidge

Calvin Coolidge

John Calvin Coolidge, Jr. was the 30th President of the United States . A Republican lawyer from Vermont, Coolidge worked his way up the ladder of Massachusetts state politics, eventually becoming governor of that state...

. As Attorney General, Stone was responsible for the appointment of J. Edgar Hoover

J. Edgar Hoover

John Edgar Hoover was the first Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation of the United States. Appointed director of the Bureau of Investigation—predecessor to the FBI—in 1924, he was instrumental in founding the FBI in 1935, where he remained director until his death in 1972...

as head of the Department of Justice's

United States Department of Justice

The United States Department of Justice , is the United States federal executive department responsible for the enforcement of the law and administration of justice, equivalent to the justice or interior ministries of other countries.The Department is led by the Attorney General, who is nominated...

Bureau of Investigation, which later became the Federal Bureau of Investigation

Federal Bureau of Investigation

The Federal Bureau of Investigation is an agency of the United States Department of Justice that serves as both a federal criminal investigative body and an internal intelligence agency . The FBI has investigative jurisdiction over violations of more than 200 categories of federal crime...

(FBI).

Associate Justice

On January 5, 1925, Stone was appointed an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court to a seat vacated by Joseph McKennaJoseph McKenna

Joseph McKenna was an American politician who served in all three branches of the U.S. federal government, as a member of the U.S. House of Representatives, as U.S. Attorney General and as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court...

, becoming Coolidge's only appointment to the Court. He was confirmed by the United States Senate

United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper house of the bicameral legislature of the United States, and together with the United States House of Representatives comprises the United States Congress. The composition and powers of the Senate are established in Article One of the U.S. Constitution. Each...

on February 5 and received his commission the same day.

During the 1932–1937 Supreme Court terms, Stone and his colleagues Justices Brandeis

Louis Brandeis

Louis Dembitz Brandeis ; November 13, 1856 – October 5, 1941) was an Associate Justice on the Supreme Court of the United States from 1916 to 1939.He was born in Louisville, Kentucky, to Jewish immigrant parents who raised him in a secular mode...

and Cardozo

Benjamin N. Cardozo

Benjamin Nathan Cardozo was a well-known American lawyer and associate Supreme Court Justice. Cardozo is remembered for his significant influence on the development of American common law in the 20th century, in addition to his modesty, philosophy, and vivid prose style...

were considered the Three Musketeers of the Supreme Court, its liberal faction. The three were highly supportive of President Roosevelt's

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt , also known by his initials, FDR, was the 32nd President of the United States and a central figure in world events during the mid-20th century, leading the United States during a time of worldwide economic crisis and world war...

New Deal

New Deal

The New Deal was a series of economic programs implemented in the United States between 1933 and 1936. They were passed by the U.S. Congress during the first term of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The programs were Roosevelt's responses to the Great Depression, and focused on what historians call...

programs, which many other Supreme Court Justices opposed. For example, he wrote for the court in United States v. Darby Lumber Co.

United States v. Darby Lumber Co.

United States v. Darby Lumber Co., 312 U.S. 100 , was a case in which the United States Supreme Court upheld the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, holding that the U.S. Congress had the power under the Commerce Clause to regulate employment conditions. The unanimous decision of the Court in this...

, , which upheld challenged provisions of the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938. Stone also authored the Court's opinion in United States v. Carolene Products Co.

United States v. Carolene Products Co.

United States v. Carolene Products Company, 304 U.S. 144 , was an April 25, 1938 decision by the United States Supreme Court. The case dealt with a federal law that prohibited filled milk from being shipped in interstate commerce...

, , which, in its famous "Footnote 4," provided a roadmap for judicial review in the post-Lochner v. New York

Lochner v. New York

Lochner vs. New York, , was a landmark United States Supreme Court case that held a "liberty of contract" was implicit in the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The case involved a New York law that limited the number of hours that a baker could work each day to ten, and limited the...

era.

Stone's support of the New Deal brought him Roosevelt's favor, and on June 12, 1941, the President elevated him to Chief Justice, a position vacated by Charles Evans Hughes

Charles Evans Hughes

Charles Evans Hughes, Sr. was an American statesman, lawyer and Republican politician from New York. He served as the 36th Governor of New York , Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States , United States Secretary of State , a judge on the Court of International Justice , and...

. Stone was confirmed by the United States Senate on June 27 and received his commission on July 3. He remained in this position for the rest of his life.

Chief Justice

As Chief Justice, Stone spoke for the Court in upholding the President's power to try Nazi saboteurs captured on AmericanUnited States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

soil by military tribunals in Ex parte Quirin

Ex parte Quirin

Ex parte Quirin, , is a Supreme Court of the United States case that upheld the jurisdiction of a United States military tribunal over the trial of several Operation Pastorius German saboteurs in the United States...

, . The court's handling of this case has been the subject of scrutiny and controversy.

Stone also wrote one of the major opinions in establishing the standard for state

U.S. state

A U.S. state is any one of the 50 federated states of the United States of America that share sovereignty with the federal government. Because of this shared sovereignty, an American is a citizen both of the federal entity and of his or her state of domicile. Four states use the official title of...

courts to have personal jurisdiction over litigants in International Shoe Co. v. Washington

International Shoe v. Washington

International Shoe Co. v. Washington, 326 U.S. 310 , was a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court in which the Court established important rules impacting a number of areas of the law including the participation of corporations involved in interstate commerce in state unemployment...

, .

As Chief Justice, Stone described the Nuremberg court

Nuremberg Trials

The Nuremberg Trials were a series of military tribunals, held by the victorious Allied forces of World War II, most notable for the prosecution of prominent members of the political, military, and economic leadership of the defeated Nazi Germany....

as "a fraud" to Germans.

He opposed overturning precedents that would have barred a Seventh-day Adventist

Seventh-day Adventist Church

The Seventh-day Adventist Church is a Protestant Christian denomination distinguished by its observance of Saturday, the original seventh day of the Judeo-Christian week, as the Sabbath, and by its emphasis on the imminent second coming of Jesus Christ...

from being naturalized as a U.S. citizen if he refused to take up military arms during wartime despite being willing to serve as a conscientious objector

Conscientious objector

A conscientious objector is an "individual who has claimed the right to refuse to perform military service" on the grounds of freedom of thought, conscience, and/or religion....

.

Stone was the fourth Chief Justice to have previously served as an Associate Justice and the second to have served in both positions consecutively. To date, Justice Stone is the only justice to have occupied all nine seniority positions on the bench, having moved from most junior Associate Justice to most senior Associate Justice and then to Chief Justice.

In 1946, at the age of 73, Stone died of a cerebral hemorrhage that struck while Justice Douglas

William O. Douglas

William Orville Douglas was an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court. With a term lasting 36 years and 209 days, he is the longest-serving justice in the history of the Supreme Court...

was reading the majority opinion in Girouard v. United States

Girouard v. United States

Girouard v. United States, , was a case decided by the Supreme Court of the United States. It concerned a pacifist applicant for naturalization who in the interview declared not to be willing to fight for the defense of the United States. The case questioned a precedent set by United States v...

from the bench; Stone had planned to read his dissent afterwards. He is the only Supreme Court Justice to have died during an open court session.

Other activities

Stone was the director of the Atlanta & Charlotte Air Line Railroad Company, the president of the Association of American Law SchoolsAssociation of American Law Schools

The Association of American Law Schools is a non-profit organization of 170 law schools in the United States. Another 25 schools are "non-member fee paid" schools, which are not members but choose to pay AALS dues. Its purpose is to improve the legal profession through the improvement of legal...

, and a member of the American Bar Association

American Bar Association

The American Bar Association , founded August 21, 1878, is a voluntary bar association of lawyers and law students, which is not specific to any jurisdiction in the United States. The ABA's most important stated activities are the setting of academic standards for law schools, and the formulation...

.

He was awarded an honorary master of arts

Master of Arts (postgraduate)

A Master of Arts from the Latin Magister Artium, is a type of Master's degree awarded by universities in many countries. The M.A. is usually contrasted with the M.S. or M.Sc. degrees...

degree from Amherst College

Amherst College

Amherst College is a private liberal arts college located in Amherst, Massachusetts, United States. Amherst is an exclusively undergraduate four-year institution and enrolled 1,744 students in the fall of 2009...

in 1900, and an honorary Doctor of Laws degree from Amherst in 1913. Yale

Yale University

Yale University is a private, Ivy League university located in New Haven, Connecticut, United States. Founded in 1701 in the Colony of Connecticut, the university is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States...

awarded him an honorary doctor of laws degree in 1924. Columbia and Williams

Williams College

Williams College is a private liberal arts college located in Williamstown, Massachusetts, United States. It was established in 1793 with funds from the estate of Ephraim Williams. Originally a men's college, Williams became co-educational in 1970. Fraternities were also phased out during this...

each awarded him the same honorary degree in 1925.

Stone married Agnes E. Harvey in 1899. Their children were Lauson H. Stone

Lauson Stone

Lauson Harvey Stone , son of US Chief Justice Harlan Stone, was US a lawyer and civic leader....

and the mathematician Marshall H. Stone

Marshall Harvey Stone

Marshall Harvey Stone was an American mathematician who contributed to real analysis, functional analysis, and the study of Boolean algebras.-Biography:...

. Stone is buried at Rock Creek Cemetery

Rock Creek Cemetery

Rock Creek Cemetery — also Rock Creek Church Yard and Cemetery — is an cemetery with a natural rolling landscape located at Rock Creek Church Road, NW, and Webster Street, NW, off Hawaii Avenue, NE in Washington, D.C.'s Michigan Park neighborhood, near Washington's Petworth neighborhood...

in the Petworth

Petworth, Washington, D.C.

Petworth is a residential neighborhood in the Northwest quadrant of Washington, D.C., bounded by Georgia Avenue to the west, North Capitol Street to the east, Rock Creek Church Road to the south, and Kennedy Street NW to the north...

neighborhood of Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly referred to as Washington, "the District", or simply D.C., is the capital of the United States. On July 16, 1790, the United States Congress approved the creation of a permanent national capital as permitted by the U.S. Constitution....

His burial is said to be "quite neighborly with other Justices even after death." Four justices buried in Rock Creek "are essentially paired off." Justice Willis Van Devanter

Willis Van Devanter

Willis Van Devanter was an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court, January 3, 1911 to June 2, 1937.- Early life and career :...

is in a family plot within 40 yards of the senior John Marshall Harlan

John Marshall Harlan

John Marshall Harlan was a Kentucky lawyer and politician who served as an associate justice on the Supreme Court. He is most notable as the lone dissenter in the Civil Rights Cases , and Plessy v...

. Chief Justice and Mrs. Harlan Fiske Stone have a "handsome memorial" within 25 yards of Stephen Johnson Field

Stephen Johnson Field

Stephen Johnson Field was an American jurist. He was an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court of the United States Supreme Court from May 20, 1863, to December 1, 1897...

's "imposing black obelisk

Obelisk

An obelisk is a tall, four-sided, narrow tapering monument which ends in a pyramid-like shape at the top, and is said to resemble a petrified ray of the sun-disk. A pair of obelisks usually stood in front of a pylon...

".

See also

- Demographics of the Supreme Court of the United StatesDemographics of the Supreme Court of the United StatesThe demographics of the Supreme Court of the United States encompass the gender, ethnic, religious, geographic, and economic backgrounds of the 112 justices appointed to the Supreme Court. Certain of these characteristics have been raised as an issue since the Court was established in 1789. For its...

- List of Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of law clerks of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of United States Chief Justices by time in office

- List of U.S. Supreme Court Justices by time in office

- United States Supreme Court cases during the Stone Court

Sources

- Attorney General biographies, Harlan Fiske Stone, United States Department of JusticeUnited States Department of JusticeThe United States Department of Justice , is the United States federal executive department responsible for the enforcement of the law and administration of justice, equivalent to the justice or interior ministries of other countries.The Department is led by the Attorney General, who is nominated...

. - Galston, Miriam. 1995. "Activism and Restraint: The Evolution of Harlan Fiske Stone's Judicial Philosophy," in Tulane Law ReviewTulane Law ReviewThe Tulane Law Review, a publication of the Tulane University Law School, was founded in 1916, and is currently published six times annually. The Law Review has an international circulation and is one of few American law reviews carried by law libraries in the United Kingdom.-History:The Law Review...

70 (November). - Konefsky, Samuel Joseph. 1945. Chief Justice Stone and the Supreme Court (Reprint, 1971. NY: Hafner)

- Mason, Alpheus Thomas, Harlan Fiske Stone: Pillar of the Law New York, Viking PressViking PressViking Press is an American publishing company owned by the Penguin Group, which has owned the company since 1975. It was founded in New York City on March 1, 1925, by Harold K. Guinzburg and George S. Oppenheim...

, 1956. ISBN 0670369977; ISBN 978-0670369973 Review of Mason, Alpheus Thomas, Harlan Fiske Stone: Pillar of the Law. - Oyez projectOyez.orgThe Oyez Project at the Chicago-Kent College of Law is an unofficial online multimedia archive of the Supreme Court of the United States, especially audio of oral arguments...

, Official Supreme Court media, Harlan Fiske Stone - Stone, Harlan Fiske. 2001. Law and Its Administration Union, N.J.: Lawbook Exchange

- Urofsky, Melvin I., Division and Discord: The Supreme Court under Stone and Vinson, 1941–1953 (University of South Carolina PressUniversity of South Carolina PressThe University of South Carolina Press , founded in 1944, is a university press that is part of the University of South Carolina.-External links:*...

, 1997) ISBN 1570031207

External links

- Ariens, Michael, Harlan Fiske Stone.

- Fox, John, Capitalism and Conflict, Biographies of the Robes, Harlan Fiske Stone Public Broadcasting ServicePublic Broadcasting ServiceThe Public Broadcasting Service is an American non-profit public broadcasting television network with 354 member TV stations in the United States which hold collective ownership. Its headquarters is in Arlington, Virginia....

. - Harlan Fiske Stone, Supreme Court Historical SocietySupreme Court Historical SocietyThe Supreme Court Historical Society is a private, non-profit organization dedicated to preserving and communicating the history of the U.S. Supreme Court.-History:...

- Nash, A. E. Kier, Harlan Fiske Stone, answers.com

- The Stone Court, 1941–1945, History of the Court, Supreme Court Historical Society

- Stone Family Papers, Special Collections, Jones Library, Amherst, MA

- Cover photograph Time Magazine