Genetic resistance to malaria

Encyclopedia

Genetic resistance to malaria occurs through both modifications of the immune system

that enhance immunity to this infection and also by changes in human red blood cell

s that hinder the malaria parasite's ability to invade and replicate within these cells. Host resistance to malaria

therefore involves not only blood cell gene

s such as abnormal hemoglobin

s, Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency

, and Duffy antigens

, which provide innate resistance, but also genes involved in immunity such as the major histocompatibility complex

genes, which regulate adaptive immune responses

. The resistance provided by modified blood cells aids survival through the dangerous years of early childhood

, while the potent protection mediated by adaptive immune responses is more important in older children and adults living where malaria is endemic

.

Malaria has placed the strongest known selective pressure

on the human genome

since the origination of agriculture

within the past 10,000 years. Several inherited variants in erythrocytes

have become common in formerly malarious parts of the world as a result of selection exerted by this parasite

. This selection was historically important as the first documented example of disease

as an agent of natural selection

in human

s. It was also the first example of genetically-controlled innate immunity

that operates early in the course of infections, preceding adaptive immunity which exerts effects after several days. In malaria, as in other diseases, innate immunity leads into, and stimulates, adaptive immunity.

(The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection

) and John Burdon Sanderson Haldane

in the United Kingdom and Sewall Wright

in the U.S.A. in the decade preceding the Second World War. Individuals of different genotypes vary in “fitness”, the probability that their genes will be passed on to the next generation. The term includes survival through reproductive age and relative fertility. Under some conditions genetic diversity (polymorphism) is stable, for example when a heterozygote has a fitness greater than that of either homozygote, whereas under other conditions polymorphism is unstable. Persons homozygous for abnormal hemoglobin (Hb) genes often have fitnesses lower than those with normal Hb, while heterozygotes have a greater fitness because of relative resistance to malaria, thereby maintaining stable polymorphisms in malarious environments.

In 2006 the World Health Organization

In 2006 the World Health Organization

estimated that there were about 250 million cases of malaria with 880,000 deaths. Approximately 90% of those who died were children in Africa

infected with Plasmodium falciparum

. Where this parasite is endemic young children have repeated malaria attacks. These are initially severe, and can be fatal, usually because of serious anemia or cerebral malaria. Repeated malaria infections strengthen adaptive immunity and broaden its effects against parasites expressing different surface antigen

s. By school age most children have developed efficacious adaptive immunity against malaria. These observations raise questions about mechanisms that favor the survival of most children in Africa while allowing some to develop potentially lethal infections. Evidence has accumulated that the first line of defense against malaria is provided by genetically-controlled innate resistance, mainly exerted by abnormal hemoglobins and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency. In malaria, as in other infections, innate immune responses lead into, and stimulate, adaptive immune responses. However, the potent effect of genetically-controlled innate resistance is reflected in the probability of survival of young children in malarious environments. It is necessary to study innate immunity in the susceptible age group, younger than four years; in older children and adults the effects of innate immunity are overshadowed by those of adaptive immunity. It is also necessary to study populations in which random use of antimalarial drug

s does not occur.

in the blood of an anemic

dental student, Walter Clement Noel. In 1927 Vernon Hahn and Elizabeth Biermann Gillespie showed that sickling of the red cells was related to low oxygen. In some individuals this change occurs at partial pressures of

prevalent in the body, and produces anemia and other disorders, termed sickle-cell disease

. In other persons sickling occurs only at very low partial pressures; these are asymptomatic sickle-cell trait carriers.

The modern phase of research on this disorder was initiated by the famous chemist Linus Pauling

in 1949. Pauling postulated that the hemoglobin

(Hb) in sickle-cell disease is abnormal; when deoxygenated it polymerizes into long, thin, helical rods that distort the red cell into a sickle shape. In his laboratory electrophoretic studies showed that sickle-cell Hb (S) is indeed abnormal, having at physiological pH

a lower negative charge than normal adult human Hb (A). In sickle-cell trait carriers there is a nearly equal amount of HbA and HbS, whereas in persons with sickle-cell disease nearly all the Hb is of the S type, apart from a small amount of fetal Hb. These observations showed that most patients with sickle-cell disease are homozygous for the gene encoding HbS, while trait carriers are heterozygous for this gene. Persons inheriting a sickle-cell gene and another mutant at the same locus. e.g. a thalassemia gene, can also have a variant form of sickle-cell disease. Pauling also introduced the term “molecular disease”, which, together with “molecular medicine

”, has become widely used.

The next major advance was the discovery by Vernon Ingram

in 1959 that HbS differs from HbA by only a single amino-acid substitution in the β-polypeptide chain (β6Glu → Val). It was later established that this results from a substitution of thymine

for adenine

in the DNA

codon (GAG → GTG). This was the first example in any species of the effects of a mutation

on a protein

. Sickle Hb induces the expression of heme oxygenase-1 in hematopoietic cells. Carbon monoxide

, a byproduct of heme catabolism by heme oxygenase

-1, prevents an accumulation of circulating free heme after Plasmodium infection, suppressing the pathogenesis of experimental cerebral malaria.

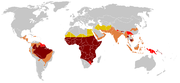

, Uganda, and Tanzania

. Later studies by many investigators filled in the picture. High frequencies of the HbS gene are confined to a broad belt across Central Africa

, but excluding most of Ethiopia

and the East African highlands; this corresponds closely to areas of malaria transmission. Sickle-cell heterozygote frequencies up to 20% also occur in pockets of India

and Greece

that were formerly highly malarious. Tens of thousands of individuals have been studied, and high frequencies of abnormal hemoglobins have not been found in any population that was malaria free.

adjacent to the β-globin gene are so close to each other that the likelihood of crossover is very small. Restriction endonuclease digests of the β-globin gene cluster have shown five distinct patterns associated with the sickle-cell (GAG → GTG) mutation. Four are observed in Africa, the Bantu, Benin

, Senegal

and Cameroon

types, and a fifth type is found in the Indian subcontinent and Arabia. The cited authors report that haplotype analysis in the β-globin region shows strong linkage disequilibrium over the distance indicated, which is evidence that the HbS mutation occurred independently at least five times. The high levels of AS in parts of Africa and India presumably resulted from independent selection occurring in different populations living in malarious environments.

In summary, the demonstration that sickle-cell heterozygotes have some degree of protection against falciparum malaria was the first example of genetically- controlled innate resistance to human malaria, as recognized by experts on inherited factors affecting human infectious diseases. It was also the first demonstration of Darwinian selection

in humans, as recognized by evolutionary biologists.

(β6Glu → Lys), which attains frequencies approaching 20% in northern Ghana and Burkina-Faso. All of these are in malarious areas, and there is evidence that the persons with α-thalassemia, HbC and HbE have some degree of protection against the parasite.

There is no longer doubt that malarial selection played a major role in the distribution of all these polymorphisms. An additional question is raised by the presence of polymorphisms for HbS and another Hb mutation in the sample population. Double heterozygotes for HbS and β-thalassemia, and for HbS and HbC, suffer from variant forms of sickle-cell disease, milder than SS but likely to reduce fitness before modern treatment was available. As predicted, these variant alleles tend to be mutually exclusive in populations. There is a negative correlation between frequencies of HbS and β-thalassemia in different parts of Greece and of HbS and HbC in West Africa. Where there is no adverse interaction of mutations, as in the case of abnormal hemoglobins and G6PD deficiency, a positive correlation of these variant alleles in populations would be expected and is found.

, has a high frequency in some Mediterranean populations, including Greeks and Southern Italians. The name is derived from the Greek words for sea (thalassa), meaning the Mediterranean sea

, and blood (haima). Vernon Ingram again deserves the credit for explaining the genetic basis of different forms of thalassemia as an imbalance in the synthesis of the two polypeptide chains of Hb. In the common Mediterranean variant, mutations decrease production of the β-chain (β thalassemia). In α-thalassemia, which is relatively frequent in Africa and several other countries, production of the α-chain of Hb is impaired, and there is relative over-production of the β-chain. Individuals homozygous for β-thalassemia have severe anemia and are unlikely to survive and reproduce, so selection against the gene is strong. Those homozygous for α thalassemia also suffer from anemia and there is some degree of selection against the gene.

(G6PD) is an important enzyme

in red cells, metabolizing glucose

through the pentose phosphate pathway

and maintaining a reducing environment. G6PD is present in all human cells but is particularly important to red blood cells. Since mature red blood cells lack nuclei

and cytoplasmic RNA

, they cannot synthesize new enzyme molecules to replace genetically abnormal or ageing ones. All proteins, including enzymes, have to last for the entire lifetime of the red blood cell, which is normally 120 days. In 1956 Alving and colleagues showed that in some African American

s the antimalarial drug primaquine

induces hemolytic anemia, and that those individuals have an inherited deficiency of G6PD in erythrocytes. G6PD deficiency

is sex linked, and common in Mediterranean, African and other populations. In Mediterranean countries such individuals can develop a hemolytic diathesis (favism) after consuming fava beans

. G6PD deficient persons are also sensitive to several drugs in addition to primaquine.

G6PD deficiency is the most common enzyme deficiency in humans, estimated to affect some 400 million people. There are many mutations at this locus, two of which attain frequencies of 20% or greater in African and Mediterranean populations; these are termed the A- and Med mutations. Mutant varieties of G6PD can be more unstable than the naturally-occurring enzyme, so that their activity declines more rapidly as red cells age.

, West Africa, following children during the period when they are most susceptible to falciparum malaria. In both cases parasite counts were significantly lower in G6PD-deficient persons than in those with normal red cell enzymes. The association has also been studied in individuals, which is possible because the enzyme deficiency is sex-linked and female heterozygotes are mosaics due to lyonization, where random inactivation of an X-chromosome in certain cells creates a population of G6PD deficient red blood cells coexisting with normal red blood cells. Malaria parasites were significantly more often observed in normal red cells than in enzyme-deficient cells. An evolutionary genetic analysis of malarial selection on G6PD deficiency genes has been published by Tishkoff and Verelli. The enzyme deficiency is common in many countries that are, or were formerly, malarious, but not elsewhere.

is an inherited condition in which erythrocytes have an oval instead of a round shape. In most populations ovalocytosis is rare, but South-East Asian ovalocytosis (SAO) occurs in as many as 15% of the indigenous people of Malaysia and of Papua New Guinea

. Several abnormalities of SAO erythrocytes have been reported, including increased red cell rigidity and reduced expression of some red cell antigens.

SAO is caused by a mutation in the gene encoding the erythrocyte band 3

protein. There is a deletion of codons 400-408 in the gene, leading to a deletion of 9 amino-acids at the boundary between the cytoplasmic and transmembrane domains of band 3 protein. Band 3 serves as the principal binding site for the membrane skeleton, a submembrane protein network composed of ankyrin

, spectrin

, actin

, and band 4.1

. Ovalocyte band 3 binds more tightly than normal band 3 to ankyrin, which connects the membrane skeleton to the band 3 anion transporter. These qualitative defects create a red blood cell membrane that is less tolerant of shear stress and more susceptible to permanent deformation.

SAO is associated with protection against cerebral malaria in children because it reduces sequestration of erythrocytes parasitized by P. falciparum in the brain microvasculature. Adhesion of P. falciparum-infected red blood cells to CD36 is enhanced by the cerebral malaria-protective SAO trait . Higher efficiency of sequestration via CD36 in SAO individuals could determine a different organ distribution of sequestered infected red blood cells. These provide a possible explanation for the selective advantage conferred by SAO against cerebral malaria.

of Nepal

and India

are highly malarial due to a warm climate and marshes sustained during the dry season by groundwater percolating down from the higher hills. Malarial forests were intentionally maintained by the rulers of Nepal as a defensive measure. Humans attempting to live in this zone suffered much higher mortality than at higher elevations or below on the drier Gangetic Plain.

However, the Tharu people had lived in this zone long enough to evolve resistance via multiple genes. Medical studies among the Tharu and non-Tharu population of the Terai

yielded the evidence that the prevalence of cases of residual malaria is nearly seven times lower among Tharus. The basis for their resistance to malaria is most likely a genetic factor. Endogamy

along caste and ethnic lines appear to have confined these to the Tharu community. Otherwise these genes probably would have become nearly universal in South Asia and beyond because of their considerable survival value and the apparent lack of negative effects comparable to Sickle Cell Anemia.

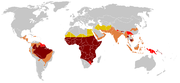

is estimated to infect 75 million people annually. P. vivax has a wide distribution in tropical countries, but is absent or rare in a large region in West and Central Africa, as recently confirmed by PCR species typing. This gap in distribution has been attributed to the lack of expression of the Duffy antigen receptor for chemokines (DARC) on the red cells of many sub-Saharan Africans. Duffy negative individuals are homozygous for a DARC allele, carrying a single nucleotide mutation (DARC 46 T → C), which impairs promoter activity by disrupting a binding site for the hGATA1 erythroid lineage transcription factor.

In widely cited in vitro and in vivo studies, Miller et al. reported that the Duffy blood group is the receptor for P. vivax and that the absence of the Duffy blood group on red cells is the resistance factor to P. vivax in persons of African descent. This has become a well-known example of innate resistance to an infectious agent because of the absence of a receptor for the agent on target cells.

However, observations have accumulated showing that the original report needs qualification. P. vivax can be transmitted in Squirrel monkey

s (Saimiri boliviensis and S. sciureus), and Barnwell et al. have obtained evidence that P. vivax enters Saimiri monkey red cells independently of the Duffy blood group, showing that P. vivax has an alternative pathway for invading these cells. The Duffy binding protein

, the one and only invasion ligand for DARC, does not bind to Saimiri erythrocytes although these cells express DARC and obviously become infected with P. vivax.

The question is whether these observations are relevant to naturally occurring human transmission of P. vivax. Ryan et al. presented evidence for the transmission of P. vivax among a Duffy-negative population in Western Kenya. Independently, Cavasini et al. have reported P. vivax infections in Duffy antigen-negative individuals from the Brazilian Amazon

region. P. vivax and Duffy antigen expression were identified by genotypic and other methods. A subsequent investigation in Madagascar

has extended these observations. The Malagasy people

in this island have an admixture of Duffy-positive and Duffy-negative people of diverse ethnic backgrounds. At eight sentinel sites covering different parts of the island 72% of the populations were Duffy-negative, as shown by genotyping and flow cytometry. P. vivax positivity was found in 8.8% of 476 asymptomatic Duffy-negative people, and clinical P. vivax malaria was found in 17 such persons. Genotyping of polymorphic and microsatellite markers suggested that multiple P. vivax strains were invading the red cells of Duffy-negative people. The authors suggest that among Malagasy populations there are enough Duffy-positive people to maintain mosquito transmission and liver infection. From this internal source P. vivax variants can develop, using receptors other than Duffy to enter red cells and multiply. More recently, Duffy negative individuals infected with two different strains (VK247 and classic strains) of P. vivax were found in Angola

and Equatorial Guinea

; further, P. vivax infections were found both in humans and mosquitoes, which means that active transmission is occurring. This finding reinforces the idea that this parasite is able to use receptors other than Duffy to invade erythrocytes, which may have an enormous impact in P. vivax current distribution. Because of these several reports from different parts of the world it is clear that some variants of P.vivax are being transmitted to humans who are not expressing DARC on their red cells. The frequency of such transmission is still unknown. Identification of the parasite and host molecules that allow Duffy-independent invasion of human erythrocytes is an important task for the future, because it may facilitate vaccine

development.

P. vivax is clearly a less potent agent of natural selection that is P. falciparum. However, the morbidity of P. vivax is not negligible. For example, P. vivax infections induce a greater inflammatory response

in the lung

s than is observed in P. falciparum infections, and progressive alveolar capillary dysfunction is observed after the treatment of vivax malaria. Epidemiological studies in the Amazonian region of Brazil have shown that the number and rate of hospital admissions for P. vivax infections have recently increased while those of P. falciparum have decreased. Standard criteria for admission were used. The authors suggest that P. vivax infections in this region are becoming more severe.

The distribution of Duffy negativity in Africa does not correlate precisely with that of P. vivax transmission. Frequencies of Duffy negativity are as high in East Africa (above 80%), where the parasite is transmitted, as they are in West Africa, where it is not. In summary, P. vivax can bind to and invade human and nonhuman primate erythrocytes through a receptor or receptors other than DARC. However, DARC still appears to be a major receptor for human transmission of P. vivax. The potency of P. vivax as an agent of natural selection is unknown, and may vary from location to location. DARC negativity remains a good example of innate resistance to an infection, but it produces a relative and not an absolute resistance to P. vivax transmission.

was traditionally attributed to phenomena such as competition for resources or predation. There was no example of natural selection operating on a common gene in humans, in contrast to selection against rare deleterious mutations. After the Second World War an Italian group (E.Silvestroni, I.Bianco and G.Montalenti) developed methods for identifying ß-thalassemia heterozygotes in populations, and recorded their frequencies in different parts of Italy

. In some regions heterozygote frequencies up to 10% were observed, and the strong geographic correspondence between the incidence of thalassemia and endemic malaria was noted, as documented by an Italian historian of science. These researches “raised clearly the question of maintaining the frequency of a gene that, at that time, doomed homozygotes to death within the first two years of life”. At an international meeting in Italy in 1949 J.B.S.Haldane gave an address on “Disease and Evolution”. In the ensuing discussion Montalenti presented information on the distribution of thalassemia in Italy, and acknowledged a suggestion from J.B.S. Haldane that thalassemic heterozygotes may be resistant to malaria. Later in 1949 Haldane reiterated the same suggestion, with no reference to the Italian investigators. Haldane is therefore widely regarded as the originator of the “malaria hypothesis”. However, there have been suggestions that the role of Italian investigators in recognizing this correlation was insufficiently acknowledged, and that opinion was also expressed by the Nobel prizewinning geneticist Joshua Lederberg

. Haldane’ general proposal that infections are important agents of natural selection was a timely reminder, but had a long parentage. It was first made by Alfred Russel Wallace

, co-discoverer of natural selection as a cause of evolution, and in the first half of the twentieth century several examples of genes conferring resistance to infections, and their implications for natural selection, were published, as noted by Lederberg. Haldane conducted no research on abnormal hemoglobins or on malaria, and malaria was eradicated from Mediterranean countries after World War II

, so the malaria hypothesis could not be validated on carriers of β-thalassemia.

in 1953. His initial study ascertained whether sickle-cell heterozygotes are protected against severe P.falciparum infections. This required working with children between four months and four years of age, when the morbidity and mortality from malaria is greatest. The study was done in Uganda

n villages where antimalarial drugs were not used. Allison found that children in this age group carrying HbS had significantly lower malaria parasite counts than in those with HbA. Severe morbidity and mortality in malaria were known to be correlated with high parasite counts. This observation has been confirmed many times in different parts of Africa, and potentially lethal manifestations of malaria (cerebral malaria and severe anemia) are rare in sickle-cell heterozygotes. In the latter study the HbS carrier state was found to be negatively associated with all potentially lethal forms of P.falciparum malaria, whereas the negative associations of the carrier states of HbC and α-thalassemia were limited to cerebral malaria and severe anemia, respectively. These findings strongly suggest that, under conditions of intense P.falciparum transmission, young sickle-cell heterozygotes (AS) survive better than those with normal hemoglobin (AA), whereas sickle-cell homozygotes (SS) survive least well of all three genotypes.

Detailed study of a cohort of 1022 Kenyan children living near Lake Victoria

, published in 2002, confirmed this prediction. Many SS children still died before they attained one year of age. Between 2 and 16 months the mortality in AS children was found to be significantly lower than that in AA children. This well-controlled investigation shows the ongoing action of natural selection through disease in a human population.

Analysis of genome-wide and fine-resolution association (GWA) is a powerful method for establishing the inheritance of resistance to infections and other diseases. Two independent preliminary analyses of GWA association with severe falciparum malaria in Africans have been carried out, one by the Malariagen Consortium in a Gambian population and the other by Rolf Horstmann (Bernhard Nocht Institute for Tropical Medicine, Hamburg) and his colleagues on a Ghanaian population. In both cases the only signal of association reaching genome-wide significance was with the HBB locus encoding the beta chain of hemoglobin, which is abnormal in HbS. This does not imply that HbS is the only gene conferring innate resistance to falciparum malaria; there could be many such genes exerting more modest effects that are challenging to detect by GWA because of the low levels of linkage disequilibrium in African populations. However the same GWA association in two populations is powerful evidence that the single gene conferring strongest innate resistance to falciparum malaria is that encoding HbS.

consumption and ingest large amounts of hemoglobin. It is likely that HbS in endocytic vesicles is deoxygenated, polymerizes and is poorly digested. In red cells containing abnormal hemoglobins, or which are G6PD deficient, oxygen radicals

are produced, and malaria parasites induce additional oxidative stress. This can result in changes in red cell membranes, including translocation of phosphatidylserine

to their surface, followed by macrophage recognition and ingestion. The authors suggest that this mechanism is likely to occur earlier in abnormal than in normal red cells, thereby restricting multiplication in the former. In addition, binding of parasitized sickle cells to endothelial cells is significantly decreased because of an altered display of P.falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein-1 (PfMP-1). This protein is the parasite’s main cytoadherence ligand and virulence factor on the cell surface. During the late stages of parasite replication red cells are adherent to venous endothelium, and inhibiting this attachment could suppress replication.

A population study has shown that the protective effect of the sickle-cell trait against falciparum malaria involves the augmentation of adaptive as well as innate immune responses to the malaria parasite, illustrating the expected transition from innate to adaptive immunity.

of different genotype

s in an African region where there is intense malarial selection were estimated by Anthony Allison in 1954. In the Baamba

population living in the Semliki Forest region in Western Uganda the sickle-cell heterozygote (AS) frequency is 40%, which means that the frequency

of the sickle-cell gene is 0.255 and 6.5 of children born are SS homozygotes. If the frequency of the heterozygote is 0.40 the sickle-cell gene frequency (q) can be calculated from the Hardy-Weinberg equation 2q(1-q) = 0,40, whence q = 0.2555 and q2, the frequency of sickle-cell homozygotes, is 0.065. It is a reasonable assumption that until modern treatment was available three quarters of the SS homozygotes failed to reproduce. To balance this loss of sickle-cell genes, a mutation rate

of 1:10.2 per gene per generation would be necessary. This is about 1000 times greater than mutation rates measured in Drosophila

and other organisms and much higher than recorded for the sickle-cell locus in Africans. To balance the polymorphism, Anthony Allison estimated that the fitness of the AS heterozygote would have to be 1.26 times than that of the normal homozygote. Later analyses of survival figures have given similar results, with some differences from site to site. In Gambians, it was estimated that AS heterozygotes have 90% protection against P.falciparum-associated severe anemia and cerebral malaria, whereas in the Luo population of Kenya it was estimated that AS heterozygotes have 60% protection against severe malarial anemia. These differences reflect the intensity of transmission of P.falciparum malaria from locality to locality and season to season, so fitness calculations will also vary. In many African populations the AS frequency is about 20%, and a fitness superiority over those with normal hemoglobin of the order of 10% is sufficient to produce a stable polymorphism.

If malarial selection is relaxed, the frequency of the sickle-cell gene will fall exponentially. This has probably occurred in the African American

population of the USA

, but the rate of fall is uncertain because of the diverse and poorly documented African origin of the population as well as mixture in the USA with immigrants

of other origins.

Human genome sequencing can be applied not only to detect the effects of natural selection but also to obtain information about how recently it occurred. Sabeti and her colleagues have provided an appropriate framework. First, haplotypes at a locus of interest are identified (core haplotypes). Then the age of each core haplotype is assessed by the decay of its association to alleles at various distances from the locus, as measured by extended haplotype homozygosity (EHH). Core haplotypes that have unusually high EHH as well as a high population prevalence reveal the presence of mutations that rose to prominence in the gene pool faster than expected by random drift. When this approach was applied to the G6PD locus, significant evidence of selection was found. A linkage-disequilibrium test was used to estimate the date of origin of the mutated G6PD gene conferring resistance, which gave a figure of about 2,500 years. Haplotype diversity and linkage disequilibrium using microsatellite data had previously been applied by Tishkoff and her colleagues to estimate the dates of origin of G6PD variants. The African A- variant was estimated to have arisen within the past 3,840 to 11,760 years and the Med variant within the past 6,640 years.

In summary, newly mutated abnormal hemoglobin and G6PD deficiency genes, arising in malarious environments, can quite rapidly become common and attain stable polymorphisms within 1,000 to 3,000 years, depending on the intensity of selection. Studies of genome variation and evolution of P.falciparum suggest that it originated within the last 3,200 to 7,700 years. These dates coincide with the spread of agriculture within the last 10,000 years, which increased the density of populations, forest clearing, and urbanization near sunlit pools of water. Such conditions favor the breeding of Anopheles mosquitos and the transmission of malaria. The dramatic changes in human social organization since the onset of the Neolithic Age

have had equally striking effects on the transmission of infectious diseases, and these, in turn, have had selective effects on human genes and left their signatures on the human genome.

Some early contributions on innate resistance to infections of vertebrates, including humans, are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Examples of Genetically Controlled Innate Resistance to Infectious Agents or Recognition of their Products

It is remarkable that two of the pioneering studies were on malaria. Type 1 interferons and their mechanism of action have been analyzed in detail by genetic and other methods. The classical studies on the Toll receptor in Drosophila

were rapidly extended to Toll like receptors in mammal

s and then to other pattern recognition receptors, which play important roles in innate immunity and its stimulation of adaptive immunity. The genetic control of innate and adaptive immunity is now a large and flourishing discipline. However, the early contributions on malaria remain as classical examples of innate resistance, which have stood the test of time.

Immune system

An immune system is a system of biological structures and processes within an organism that protects against disease by identifying and killing pathogens and tumor cells. It detects a wide variety of agents, from viruses to parasitic worms, and needs to distinguish them from the organism's own...

that enhance immunity to this infection and also by changes in human red blood cell

Red blood cell

Red blood cells are the most common type of blood cell and the vertebrate organism's principal means of delivering oxygen to the body tissues via the blood flow through the circulatory system...

s that hinder the malaria parasite's ability to invade and replicate within these cells. Host resistance to malaria

Malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease of humans and other animals caused by eukaryotic protists of the genus Plasmodium. The disease results from the multiplication of Plasmodium parasites within red blood cells, causing symptoms that typically include fever and headache, in severe cases...

therefore involves not only blood cell gene

Gene

A gene is a molecular unit of heredity of a living organism. It is a name given to some stretches of DNA and RNA that code for a type of protein or for an RNA chain that has a function in the organism. Living beings depend on genes, as they specify all proteins and functional RNA chains...

s such as abnormal hemoglobin

Hemoglobin

Hemoglobin is the iron-containing oxygen-transport metalloprotein in the red blood cells of all vertebrates, with the exception of the fish family Channichthyidae, as well as the tissues of some invertebrates...

s, Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency

Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency

Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency is an X-linked recessive hereditary disease characterised by abnormally low levels of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase , a metabolic enzyme involved in the pentose phosphate pathway, especially important in red blood cell metabolism. G6PD deficiency is...

, and Duffy antigens

Duffy antigen system

Duffy antigen/chemokine receptor also known as Fy glycoprotein or CD234 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the DARC gene....

, which provide innate resistance, but also genes involved in immunity such as the major histocompatibility complex

Major histocompatibility complex

Major histocompatibility complex is a cell surface molecule encoded by a large gene family in all vertebrates. MHC molecules mediate interactions of leukocytes, also called white blood cells , which are immune cells, with other leukocytes or body cells...

genes, which regulate adaptive immune responses

Adaptive immune system

The adaptive immune system is composed of highly specialized, systemic cells and processes that eliminate or prevent pathogenic growth. Thought to have arisen in the first jawed vertebrates, the adaptive or "specific" immune system is activated by the “non-specific” and evolutionarily older innate...

. The resistance provided by modified blood cells aids survival through the dangerous years of early childhood

Childhood

Childhood is the age span ranging from birth to adolescence. In developmental psychology, childhood is divided up into the developmental stages of toddlerhood , early childhood , middle childhood , and adolescence .- Age ranges of childhood :The term childhood is non-specific and can imply a...

, while the potent protection mediated by adaptive immune responses is more important in older children and adults living where malaria is endemic

Endemic (epidemiology)

In epidemiology, an infection is said to be endemic in a population when that infection is maintained in the population without the need for external inputs. For example, chickenpox is endemic in the UK, but malaria is not...

.

Malaria has placed the strongest known selective pressure

Evolutionary pressure

Any cause that reduces reproductive success in a proportion of a population, potentially exerts evolutionary pressure or selection pressure. With sufficient pressure, inherited traits that mitigate its effects - even if they would be deleterious in other circumstances - can become widely spread...

on the human genome

Human genome

The human genome is the genome of Homo sapiens, which is stored on 23 chromosome pairs plus the small mitochondrial DNA. 22 of the 23 chromosomes are autosomal chromosome pairs, while the remaining pair is sex-determining...

since the origination of agriculture

Agriculture

Agriculture is the cultivation of animals, plants, fungi and other life forms for food, fiber, and other products used to sustain life. Agriculture was the key implement in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that nurtured the...

within the past 10,000 years. Several inherited variants in erythrocytes

Red blood cell

Red blood cells are the most common type of blood cell and the vertebrate organism's principal means of delivering oxygen to the body tissues via the blood flow through the circulatory system...

have become common in formerly malarious parts of the world as a result of selection exerted by this parasite

Parasitism

Parasitism is a type of symbiotic relationship between organisms of different species where one organism, the parasite, benefits at the expense of the other, the host. Traditionally parasite referred to organisms with lifestages that needed more than one host . These are now called macroparasites...

. This selection was historically important as the first documented example of disease

Disease

A disease is an abnormal condition affecting the body of an organism. It is often construed to be a medical condition associated with specific symptoms and signs. It may be caused by external factors, such as infectious disease, or it may be caused by internal dysfunctions, such as autoimmune...

as an agent of natural selection

Natural selection

Natural selection is the nonrandom process by which biologic traits become either more or less common in a population as a function of differential reproduction of their bearers. It is a key mechanism of evolution....

in human

Human

Humans are the only living species in the Homo genus...

s. It was also the first example of genetically-controlled innate immunity

Innate immune system

The innate immune system, also known as non-specific immune system and secondary line of defence, comprises the cells and mechanisms that defend the host from infection by other organisms in a non-specific manner...

that operates early in the course of infections, preceding adaptive immunity which exerts effects after several days. In malaria, as in other diseases, innate immunity leads into, and stimulates, adaptive immunity.

Population genetics

Evolution results from changes in gene frequencies in populations. The rates at which gene frequencies change, and the conditions under which they remain stable, were defined by the mathematical analyses of Ronald FisherRonald Fisher

Sir Ronald Aylmer Fisher FRS was an English statistician, evolutionary biologist, eugenicist and geneticist. Among other things, Fisher is well known for his contributions to statistics by creating Fisher's exact test and Fisher's equation...

(The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection

The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection

The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection is a book by R.A. Fisher first published in 1930 by Clarendon. It is one of the most important books of the modern evolutionary synthesis and is commonly cited in biology books.-Editions:...

) and John Burdon Sanderson Haldane

J. B. S. Haldane

John Burdon Sanderson Haldane FRS , known as Jack , was a British-born geneticist and evolutionary biologist. A staunch Marxist, he was critical of Britain's role in the Suez Crisis, and chose to leave Oxford and moved to India and became an Indian citizen...

in the United Kingdom and Sewall Wright

Sewall Wright

Sewall Green Wright was an American geneticist known for his influential work on evolutionary theory and also for his work on path analysis. With R. A. Fisher and J.B.S. Haldane, he was a founder of theoretical population genetics. He is the discoverer of the inbreeding coefficient and of...

in the U.S.A. in the decade preceding the Second World War. Individuals of different genotypes vary in “fitness”, the probability that their genes will be passed on to the next generation. The term includes survival through reproductive age and relative fertility. Under some conditions genetic diversity (polymorphism) is stable, for example when a heterozygote has a fitness greater than that of either homozygote, whereas under other conditions polymorphism is unstable. Persons homozygous for abnormal hemoglobin (Hb) genes often have fitnesses lower than those with normal Hb, while heterozygotes have a greater fitness because of relative resistance to malaria, thereby maintaining stable polymorphisms in malarious environments.

Natural history of infections

World Health Organization

The World Health Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations that acts as a coordinating authority on international public health. Established on 7 April 1948, with headquarters in Geneva, Switzerland, the agency inherited the mandate and resources of its predecessor, the Health...

estimated that there were about 250 million cases of malaria with 880,000 deaths. Approximately 90% of those who died were children in Africa

Africa

Africa is the world's second largest and second most populous continent, after Asia. At about 30.2 million km² including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of the Earth's total surface area and 20.4% of the total land area...

infected with Plasmodium falciparum

Plasmodium falciparum

Plasmodium falciparum is a protozoan parasite, one of the species of Plasmodium that cause malaria in humans. It is transmitted by the female Anopheles mosquito. Malaria caused by this species is the most dangerous form of malaria, with the highest rates of complications and mortality...

. Where this parasite is endemic young children have repeated malaria attacks. These are initially severe, and can be fatal, usually because of serious anemia or cerebral malaria. Repeated malaria infections strengthen adaptive immunity and broaden its effects against parasites expressing different surface antigen

Antigen

An antigen is a foreign molecule that, when introduced into the body, triggers the production of an antibody by the immune system. The immune system will then kill or neutralize the antigen that is recognized as a foreign and potentially harmful invader. These invaders can be molecules such as...

s. By school age most children have developed efficacious adaptive immunity against malaria. These observations raise questions about mechanisms that favor the survival of most children in Africa while allowing some to develop potentially lethal infections. Evidence has accumulated that the first line of defense against malaria is provided by genetically-controlled innate resistance, mainly exerted by abnormal hemoglobins and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency. In malaria, as in other infections, innate immune responses lead into, and stimulate, adaptive immune responses. However, the potent effect of genetically-controlled innate resistance is reflected in the probability of survival of young children in malarious environments. It is necessary to study innate immunity in the susceptible age group, younger than four years; in older children and adults the effects of innate immunity are overshadowed by those of adaptive immunity. It is also necessary to study populations in which random use of antimalarial drug

Antimalarial drug

Antimalarial medications, also known as antimalarials, are designed to prevent or cure malaria. Such drugs may be used for some or all of the following:* Treatment of malaria in individuals with suspected or confirmed infection...

s does not occur.

Sickle-cell

In 1910 a Chicago physician, James B. Herrick, observed sickle cellsSickle cell trait

Sickle cell trait describes a condition in which a person has one abnormal allele of the hemoglobin beta gene , but does not display the severe symptoms of sickle cell disease that occur in a person who has two copies of that allele...

in the blood of an anemic

Anemia

Anemia is a decrease in number of red blood cells or less than the normal quantity of hemoglobin in the blood. However, it can include decreased oxygen-binding ability of each hemoglobin molecule due to deformity or lack in numerical development as in some other types of hemoglobin...

dental student, Walter Clement Noel. In 1927 Vernon Hahn and Elizabeth Biermann Gillespie showed that sickling of the red cells was related to low oxygen. In some individuals this change occurs at partial pressures of

Oxygen

Oxygen is the element with atomic number 8 and represented by the symbol O. Its name derives from the Greek roots ὀξύς and -γενής , because at the time of naming, it was mistakenly thought that all acids required oxygen in their composition...

prevalent in the body, and produces anemia and other disorders, termed sickle-cell disease

Sickle-cell disease

Sickle-cell disease , or sickle-cell anaemia or drepanocytosis, is an autosomal recessive genetic blood disorder with overdominance, characterized by red blood cells that assume an abnormal, rigid, sickle shape. Sickling decreases the cells' flexibility and results in a risk of various...

. In other persons sickling occurs only at very low partial pressures; these are asymptomatic sickle-cell trait carriers.

The modern phase of research on this disorder was initiated by the famous chemist Linus Pauling

Linus Pauling

Linus Carl Pauling was an American chemist, biochemist, peace activist, author, and educator. He was one of the most influential chemists in history and ranks among the most important scientists of the 20th century...

in 1949. Pauling postulated that the hemoglobin

Hemoglobin

Hemoglobin is the iron-containing oxygen-transport metalloprotein in the red blood cells of all vertebrates, with the exception of the fish family Channichthyidae, as well as the tissues of some invertebrates...

(Hb) in sickle-cell disease is abnormal; when deoxygenated it polymerizes into long, thin, helical rods that distort the red cell into a sickle shape. In his laboratory electrophoretic studies showed that sickle-cell Hb (S) is indeed abnormal, having at physiological pH

PH

In chemistry, pH is a measure of the acidity or basicity of an aqueous solution. Pure water is said to be neutral, with a pH close to 7.0 at . Solutions with a pH less than 7 are said to be acidic and solutions with a pH greater than 7 are basic or alkaline...

a lower negative charge than normal adult human Hb (A). In sickle-cell trait carriers there is a nearly equal amount of HbA and HbS, whereas in persons with sickle-cell disease nearly all the Hb is of the S type, apart from a small amount of fetal Hb. These observations showed that most patients with sickle-cell disease are homozygous for the gene encoding HbS, while trait carriers are heterozygous for this gene. Persons inheriting a sickle-cell gene and another mutant at the same locus. e.g. a thalassemia gene, can also have a variant form of sickle-cell disease. Pauling also introduced the term “molecular disease”, which, together with “molecular medicine

Molecular medicine

Molecular medicine is a broad field, where physical, chemical, biological and medical techniques are used to describe molecular structures and mechanisms, identify fundamental molecular and genetic errors of disease, and to develop molecular interventions to correct them...

”, has become widely used.

The next major advance was the discovery by Vernon Ingram

Vernon Ingram

Vernon M. Ingram, Ph.D., FRS was a German American professor of biology at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.-Biography:Ingram was born in Breslau, Lower Silesia...

in 1959 that HbS differs from HbA by only a single amino-acid substitution in the β-polypeptide chain (β6Glu → Val). It was later established that this results from a substitution of thymine

Thymine

Thymine is one of the four nucleobases in the nucleic acid of DNA that are represented by the letters G–C–A–T. The others are adenine, guanine, and cytosine. Thymine is also known as 5-methyluracil, a pyrimidine nucleobase. As the name suggests, thymine may be derived by methylation of uracil at...

for adenine

Adenine

Adenine is a nucleobase with a variety of roles in biochemistry including cellular respiration, in the form of both the energy-rich adenosine triphosphate and the cofactors nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide and flavin adenine dinucleotide , and protein synthesis, as a chemical component of DNA...

in the DNA

DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid is a nucleic acid that contains the genetic instructions used in the development and functioning of all known living organisms . The DNA segments that carry this genetic information are called genes, but other DNA sequences have structural purposes, or are involved in...

codon (GAG → GTG). This was the first example in any species of the effects of a mutation

Mutation

In molecular biology and genetics, mutations are changes in a genomic sequence: the DNA sequence of a cell's genome or the DNA or RNA sequence of a virus. They can be defined as sudden and spontaneous changes in the cell. Mutations are caused by radiation, viruses, transposons and mutagenic...

on a protein

Protein

Proteins are biochemical compounds consisting of one or more polypeptides typically folded into a globular or fibrous form, facilitating a biological function. A polypeptide is a single linear polymer chain of amino acids bonded together by peptide bonds between the carboxyl and amino groups of...

. Sickle Hb induces the expression of heme oxygenase-1 in hematopoietic cells. Carbon monoxide

Carbon monoxide

Carbon monoxide , also called carbonous oxide, is a colorless, odorless, and tasteless gas that is slightly lighter than air. It is highly toxic to humans and animals in higher quantities, although it is also produced in normal animal metabolism in low quantities, and is thought to have some normal...

, a byproduct of heme catabolism by heme oxygenase

Heme oxygenase

This reaction can occur in virtually every cell; the classic example is the formation of a bruise, which goes through different colors as it gradually heals: red heme to green biliverdin to yellow bilirubin...

-1, prevents an accumulation of circulating free heme after Plasmodium infection, suppressing the pathogenesis of experimental cerebral malaria.

Distribution of the sickle-cell gene

Since sickle-cell homozygotes are at a strong selective disadvantage, while protection against malaria favors the heterozygotes, it would be expected that high frequencies of the HbS gene would be found only in populations living in regions where malaria transmission is intense, or was so until the disease was eradicated. In a second study conducted in 1953 Allison showed that this was true in East Africa. Frequencies of sickle-cell heterozygotes were 20-40% in malarious areas, whereas they were very low or zero in the highlands of KenyaKenya

Kenya , officially known as the Republic of Kenya, is a country in East Africa that lies on the equator, with the Indian Ocean to its south-east...

, Uganda, and Tanzania

Tanzania

The United Republic of Tanzania is a country in East Africa bordered by Kenya and Uganda to the north, Rwanda, Burundi, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo to the west, and Zambia, Malawi, and Mozambique to the south. The country's eastern borders lie on the Indian Ocean.Tanzania is a state...

. Later studies by many investigators filled in the picture. High frequencies of the HbS gene are confined to a broad belt across Central Africa

Central Africa

Central Africa is a core region of the African continent which includes Burundi, the Central African Republic, Chad, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Rwanda....

, but excluding most of Ethiopia

Ethiopia

Ethiopia , officially known as the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a country located in the Horn of Africa. It is the second-most populous nation in Africa, with over 82 million inhabitants, and the tenth-largest by area, occupying 1,100,000 km2...

and the East African highlands; this corresponds closely to areas of malaria transmission. Sickle-cell heterozygote frequencies up to 20% also occur in pockets of India

India

India , officially the Republic of India , is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by geographical area, the second-most populous country with over 1.2 billion people, and the most populous democracy in the world...

and Greece

Greece

Greece , officially the Hellenic Republic , and historically Hellas or the Republic of Greece in English, is a country in southeastern Europe....

that were formerly highly malarious. Tens of thousands of individuals have been studied, and high frequencies of abnormal hemoglobins have not been found in any population that was malaria free.

Independent origins of the sickle-cell gene

Two mutations found in nontranscribed sequences of DNADNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid is a nucleic acid that contains the genetic instructions used in the development and functioning of all known living organisms . The DNA segments that carry this genetic information are called genes, but other DNA sequences have structural purposes, or are involved in...

adjacent to the β-globin gene are so close to each other that the likelihood of crossover is very small. Restriction endonuclease digests of the β-globin gene cluster have shown five distinct patterns associated with the sickle-cell (GAG → GTG) mutation. Four are observed in Africa, the Bantu, Benin

Benin

Benin , officially the Republic of Benin, is a country in West Africa. It borders Togo to the west, Nigeria to the east and Burkina Faso and Niger to the north. Its small southern coastline on the Bight of Benin is where a majority of the population is located...

, Senegal

Senegal

Senegal , officially the Republic of Senegal , is a country in western Africa. It owes its name to the Sénégal River that borders it to the east and north...

and Cameroon

Cameroon

Cameroon, officially the Republic of Cameroon , is a country in west Central Africa. It is bordered by Nigeria to the west; Chad to the northeast; the Central African Republic to the east; and Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, and the Republic of the Congo to the south. Cameroon's coastline lies on the...

types, and a fifth type is found in the Indian subcontinent and Arabia. The cited authors report that haplotype analysis in the β-globin region shows strong linkage disequilibrium over the distance indicated, which is evidence that the HbS mutation occurred independently at least five times. The high levels of AS in parts of Africa and India presumably resulted from independent selection occurring in different populations living in malarious environments.

In summary, the demonstration that sickle-cell heterozygotes have some degree of protection against falciparum malaria was the first example of genetically- controlled innate resistance to human malaria, as recognized by experts on inherited factors affecting human infectious diseases. It was also the first demonstration of Darwinian selection

Darwinism

Darwinism is a set of movements and concepts related to ideas of transmutation of species or of evolution, including some ideas with no connection to the work of Charles Darwin....

in humans, as recognized by evolutionary biologists.

Other abnormal hemoglobins

The frequencies of abnormal hemoglobins in different populations vary greatly, but some are undoubtedly polymorphic, having frequencies higher than expected by recurrent mutation. Four of these are α-thalassemia, which attains frequencies of 30% in parts of West Africa; β-thalassemia, with frequencies up to 10% in parts of Italy; HbE (β26Glu → Lys), which attains frequencies up to 55% in Thailand and other Southeast Asian countries; and HbCHemoglobin C

Hemoglobin C is an abnormal hemoglobin with substitution of a lysine residue for a glutamic acid residue at the 6th position of the β-globin chain.-Clinical significance:...

(β6Glu → Lys), which attains frequencies approaching 20% in northern Ghana and Burkina-Faso. All of these are in malarious areas, and there is evidence that the persons with α-thalassemia, HbC and HbE have some degree of protection against the parasite.

There is no longer doubt that malarial selection played a major role in the distribution of all these polymorphisms. An additional question is raised by the presence of polymorphisms for HbS and another Hb mutation in the sample population. Double heterozygotes for HbS and β-thalassemia, and for HbS and HbC, suffer from variant forms of sickle-cell disease, milder than SS but likely to reduce fitness before modern treatment was available. As predicted, these variant alleles tend to be mutually exclusive in populations. There is a negative correlation between frequencies of HbS and β-thalassemia in different parts of Greece and of HbS and HbC in West Africa. Where there is no adverse interaction of mutations, as in the case of abnormal hemoglobins and G6PD deficiency, a positive correlation of these variant alleles in populations would be expected and is found.

Thalassemias

It has long been known that a kind of anemia, termed thalassemiaThalassemia

Thalassemia is an inherited autosomal recessive blood disease that originated in the Mediterranean region. In thalassemia the genetic defect, which could be either mutation or deletion, results in reduced rate of synthesis or no synthesis of one of the globin chains that make up hemoglobin...

, has a high frequency in some Mediterranean populations, including Greeks and Southern Italians. The name is derived from the Greek words for sea (thalassa), meaning the Mediterranean sea

Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean surrounded by the Mediterranean region and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Anatolia and Europe, on the south by North Africa, and on the east by the Levant...

, and blood (haima). Vernon Ingram again deserves the credit for explaining the genetic basis of different forms of thalassemia as an imbalance in the synthesis of the two polypeptide chains of Hb. In the common Mediterranean variant, mutations decrease production of the β-chain (β thalassemia). In α-thalassemia, which is relatively frequent in Africa and several other countries, production of the α-chain of Hb is impaired, and there is relative over-production of the β-chain. Individuals homozygous for β-thalassemia have severe anemia and are unlikely to survive and reproduce, so selection against the gene is strong. Those homozygous for α thalassemia also suffer from anemia and there is some degree of selection against the gene.

Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency

Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenaseGlucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase

Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase is a cytosolic enzyme in the pentose phosphate pathway , a metabolic pathway that supplies reducing energy to cells by maintaining the level of the co-enzyme nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate...

(G6PD) is an important enzyme

Enzyme

Enzymes are proteins that catalyze chemical reactions. In enzymatic reactions, the molecules at the beginning of the process, called substrates, are converted into different molecules, called products. Almost all chemical reactions in a biological cell need enzymes in order to occur at rates...

in red cells, metabolizing glucose

Glucose

Glucose is a simple sugar and an important carbohydrate in biology. Cells use it as the primary source of energy and a metabolic intermediate...

through the pentose phosphate pathway

Pentose phosphate pathway

The pentose phosphate pathway is a process that generates NADPH and pentoses . There are two distinct phases in the pathway. The first is the oxidative phase, in which NADPH is generated, and the second is the non-oxidative synthesis of 5-carbon sugars...

and maintaining a reducing environment. G6PD is present in all human cells but is particularly important to red blood cells. Since mature red blood cells lack nuclei

Cell nucleus

In cell biology, the nucleus is a membrane-enclosed organelle found in eukaryotic cells. It contains most of the cell's genetic material, organized as multiple long linear DNA molecules in complex with a large variety of proteins, such as histones, to form chromosomes. The genes within these...

and cytoplasmic RNA

RNA

Ribonucleic acid , or RNA, is one of the three major macromolecules that are essential for all known forms of life....

, they cannot synthesize new enzyme molecules to replace genetically abnormal or ageing ones. All proteins, including enzymes, have to last for the entire lifetime of the red blood cell, which is normally 120 days. In 1956 Alving and colleagues showed that in some African American

African American

African Americans are citizens or residents of the United States who have at least partial ancestry from any of the native populations of Sub-Saharan Africa and are the direct descendants of enslaved Africans within the boundaries of the present United States...

s the antimalarial drug primaquine

Primaquine

Primaquine is a medication used in the treatment of malaria and Pneumocystis pneumonia. It is a member of the 8-aminoquinoline group of drugs that includes tafenoquine and pamaquine.-Radical cure:...

induces hemolytic anemia, and that those individuals have an inherited deficiency of G6PD in erythrocytes. G6PD deficiency

Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency

Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency is an X-linked recessive hereditary disease characterised by abnormally low levels of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase , a metabolic enzyme involved in the pentose phosphate pathway, especially important in red blood cell metabolism. G6PD deficiency is...

is sex linked, and common in Mediterranean, African and other populations. In Mediterranean countries such individuals can develop a hemolytic diathesis (favism) after consuming fava beans

Vicia faba

This article refers to the Broad Bean plant. For Broadbean the company, see Broadbean, Inc.Vicia faba, the Broad Bean, Fava Bean, Field Bean, Bell Bean or Tic Bean, is a species of bean native to north Africa and southwest Asia, and extensively cultivated elsewhere. A variety is provisionally...

. G6PD deficient persons are also sensitive to several drugs in addition to primaquine.

G6PD deficiency is the most common enzyme deficiency in humans, estimated to affect some 400 million people. There are many mutations at this locus, two of which attain frequencies of 20% or greater in African and Mediterranean populations; these are termed the A- and Med mutations. Mutant varieties of G6PD can be more unstable than the naturally-occurring enzyme, so that their activity declines more rapidly as red cells age.

Malaria in G6PD-deficient subjects

This question has been studied in isolated populations where antimalarial drugs were not used in Tanzania, East Africa and The GambiaThe Gambia

The Republic of The Gambia, commonly referred to as The Gambia, or Gambia , is a country in West Africa. Gambia is the smallest country on mainland Africa, surrounded by Senegal except for a short coastline on the Atlantic Ocean in the west....

, West Africa, following children during the period when they are most susceptible to falciparum malaria. In both cases parasite counts were significantly lower in G6PD-deficient persons than in those with normal red cell enzymes. The association has also been studied in individuals, which is possible because the enzyme deficiency is sex-linked and female heterozygotes are mosaics due to lyonization, where random inactivation of an X-chromosome in certain cells creates a population of G6PD deficient red blood cells coexisting with normal red blood cells. Malaria parasites were significantly more often observed in normal red cells than in enzyme-deficient cells. An evolutionary genetic analysis of malarial selection on G6PD deficiency genes has been published by Tishkoff and Verelli. The enzyme deficiency is common in many countries that are, or were formerly, malarious, but not elsewhere.

South-East Asian ovalocytosis

OvalocytosisOvalocytosis

Southeast Asian ovalocytosis is a form of hereditary elliptocytosis common in some communities in Malaysia and Papua New Guinea, as it confers some resistance to cerebral Falciparum Malaria.-Southeast Asian ovalocytosis:...

is an inherited condition in which erythrocytes have an oval instead of a round shape. In most populations ovalocytosis is rare, but South-East Asian ovalocytosis (SAO) occurs in as many as 15% of the indigenous people of Malaysia and of Papua New Guinea

Papua New Guinea

Papua New Guinea , officially the Independent State of Papua New Guinea, is a country in Oceania, occupying the eastern half of the island of New Guinea and numerous offshore islands...

. Several abnormalities of SAO erythrocytes have been reported, including increased red cell rigidity and reduced expression of some red cell antigens.

SAO is caused by a mutation in the gene encoding the erythrocyte band 3

Band 3

Anion Exchanger 1 or Band 3 is a phylogenetically preserved transport protein responsible for mediating the exchange of chloride for bicarbonate across a plasma membrane. Functionally similar members of the AE clade are AE2 and AE3.It is ubiquitous throughout the vertebrates...

protein. There is a deletion of codons 400-408 in the gene, leading to a deletion of 9 amino-acids at the boundary between the cytoplasmic and transmembrane domains of band 3 protein. Band 3 serves as the principal binding site for the membrane skeleton, a submembrane protein network composed of ankyrin

Ankyrin

Ankyrins are a family of adaptor proteins that mediate the attachment of integral membrane proteins to the spectrin-actin based membrane skeleton. Ankyrins have binding sites for the beta subunit of spectrin and at least 12 families of integral membrane proteins...

, spectrin

Spectrin

Spectrin is a cytoskeletal protein that lines the intracellular side of the plasma membrane of many cell types in pentagonal or hexagonal arrangements, forming a scaffolding and playing an important role in maintenance of plasma membrane integrity and cytoskeletal structure...

, actin

Actin

Actin is a globular, roughly 42-kDa moonlighting protein found in all eukaryotic cells where it may be present at concentrations of over 100 μM. It is also one of the most highly-conserved proteins, differing by no more than 20% in species as diverse as algae and humans...

, and band 4.1

Band 4.1

Protein 4.1, also known as Beatty's Protein, is a protein associated with the cytoskeleton that in humans is encoded by the EPB41 gene.Protein 4.1 is a major structural element of the erythrocyte membrane skeleton. It plays a key role in regulating membrane physical properties of mechanical...

. Ovalocyte band 3 binds more tightly than normal band 3 to ankyrin, which connects the membrane skeleton to the band 3 anion transporter. These qualitative defects create a red blood cell membrane that is less tolerant of shear stress and more susceptible to permanent deformation.

SAO is associated with protection against cerebral malaria in children because it reduces sequestration of erythrocytes parasitized by P. falciparum in the brain microvasculature. Adhesion of P. falciparum-infected red blood cells to CD36 is enhanced by the cerebral malaria-protective SAO trait . Higher efficiency of sequestration via CD36 in SAO individuals could determine a different organ distribution of sequestered infected red blood cells. These provide a possible explanation for the selective advantage conferred by SAO against cerebral malaria.

Resistance in South Asia

The lowest Himalayan Foothills and Inner Terai or Doon ValleysInner Terai Valleys of Nepal

The Inner Terai Valleys or Bhitri tarai are various elongated valleys in Nepal situated between the Himalayan foothills, the 600–900 m high Siwalik or Churia Range and the 2,000-3,000 m high Mahabharat Range further north. Major examples are the Chitwan Valley southwest of Kathmandu and the...

of Nepal

Nepal

Nepal , officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal, is a landlocked sovereign state located in South Asia. It is located in the Himalayas and bordered to the north by the People's Republic of China, and to the south, east, and west by the Republic of India...

and India

India

India , officially the Republic of India , is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by geographical area, the second-most populous country with over 1.2 billion people, and the most populous democracy in the world...

are highly malarial due to a warm climate and marshes sustained during the dry season by groundwater percolating down from the higher hills. Malarial forests were intentionally maintained by the rulers of Nepal as a defensive measure. Humans attempting to live in this zone suffered much higher mortality than at higher elevations or below on the drier Gangetic Plain.

However, the Tharu people had lived in this zone long enough to evolve resistance via multiple genes. Medical studies among the Tharu and non-Tharu population of the Terai

Terai

The Terai is a belt of marshy grasslands, savannas, and forests located south of the outer foothills of the Himalaya, the Siwalik Hills, and north of the Indo-Gangetic Plain of the Ganges, Brahmaputra and their tributaries. The Terai belongs to the Terai-Duar savanna and grasslands ecoregion...

yielded the evidence that the prevalence of cases of residual malaria is nearly seven times lower among Tharus. The basis for their resistance to malaria is most likely a genetic factor. Endogamy

Endogamy

Endogamy is the practice of marrying within a specific ethnic group, class, or social group, rejecting others on such basis as being unsuitable for marriage or other close personal relationships. A Greek Orthodox Christian endogamist, for example, would require that a marriage be only with another...

along caste and ethnic lines appear to have confined these to the Tharu community. Otherwise these genes probably would have become nearly universal in South Asia and beyond because of their considerable survival value and the apparent lack of negative effects comparable to Sickle Cell Anemia.

Duffy antigen receptor

The malaria parasite Plasmodium vivaxPlasmodium vivax

Plasmodium vivax is a protozoal parasite and a human pathogen. The most frequent and widely distributed cause of recurring malaria, P. vivax is one of the four species of malarial parasite that commonly infect humans. It is less virulent than Plasmodium falciparum, which is the deadliest of the...

is estimated to infect 75 million people annually. P. vivax has a wide distribution in tropical countries, but is absent or rare in a large region in West and Central Africa, as recently confirmed by PCR species typing. This gap in distribution has been attributed to the lack of expression of the Duffy antigen receptor for chemokines (DARC) on the red cells of many sub-Saharan Africans. Duffy negative individuals are homozygous for a DARC allele, carrying a single nucleotide mutation (DARC 46 T → C), which impairs promoter activity by disrupting a binding site for the hGATA1 erythroid lineage transcription factor.

In widely cited in vitro and in vivo studies, Miller et al. reported that the Duffy blood group is the receptor for P. vivax and that the absence of the Duffy blood group on red cells is the resistance factor to P. vivax in persons of African descent. This has become a well-known example of innate resistance to an infectious agent because of the absence of a receptor for the agent on target cells.

However, observations have accumulated showing that the original report needs qualification. P. vivax can be transmitted in Squirrel monkey

Squirrel monkey

The squirrel monkeys are the New World monkeys of the genus Saimiri. They are the only genus in the subfamily Saimirinae.Squirrel monkeys live in the tropical forests of Central and South America in the canopy layer. Most species have parapatric or allopatric ranges in the Amazon, while S...

s (Saimiri boliviensis and S. sciureus), and Barnwell et al. have obtained evidence that P. vivax enters Saimiri monkey red cells independently of the Duffy blood group, showing that P. vivax has an alternative pathway for invading these cells. The Duffy binding protein

Duffy binding proteins

In molecular biology, Duffy binding proteins are found in plasmodia. Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium knowlesi merozoites invade Homo sapiens erythrocytes that express Duffy blood group surface determinants. The Duffy receptor family is localised in micronemes, an organelle found in all organisms of...

, the one and only invasion ligand for DARC, does not bind to Saimiri erythrocytes although these cells express DARC and obviously become infected with P. vivax.

The question is whether these observations are relevant to naturally occurring human transmission of P. vivax. Ryan et al. presented evidence for the transmission of P. vivax among a Duffy-negative population in Western Kenya. Independently, Cavasini et al. have reported P. vivax infections in Duffy antigen-negative individuals from the Brazilian Amazon

Amazon River

The Amazon of South America is the second longest river in the world and by far the largest by waterflow with an average discharge greater than the next seven largest rivers combined...

region. P. vivax and Duffy antigen expression were identified by genotypic and other methods. A subsequent investigation in Madagascar

Madagascar

The Republic of Madagascar is an island country located in the Indian Ocean off the southeastern coast of Africa...

has extended these observations. The Malagasy people

Malagasy people

The Malagasy ethnic group forms nearly the entire population of Madagascar. They are divided into two subgroups: the "Highlander" Merina, Sihanaka and Betsileo of the central plateau around Antananarivo, Alaotra and Fianarantsoa, and the côtiers elsewhere in the country. This division has its...

in this island have an admixture of Duffy-positive and Duffy-negative people of diverse ethnic backgrounds. At eight sentinel sites covering different parts of the island 72% of the populations were Duffy-negative, as shown by genotyping and flow cytometry. P. vivax positivity was found in 8.8% of 476 asymptomatic Duffy-negative people, and clinical P. vivax malaria was found in 17 such persons. Genotyping of polymorphic and microsatellite markers suggested that multiple P. vivax strains were invading the red cells of Duffy-negative people. The authors suggest that among Malagasy populations there are enough Duffy-positive people to maintain mosquito transmission and liver infection. From this internal source P. vivax variants can develop, using receptors other than Duffy to enter red cells and multiply. More recently, Duffy negative individuals infected with two different strains (VK247 and classic strains) of P. vivax were found in Angola

Angola

Angola, officially the Republic of Angola , is a country in south-central Africa bordered by Namibia on the south, the Democratic Republic of the Congo on the north, and Zambia on the east; its west coast is on the Atlantic Ocean with Luanda as its capital city...

and Equatorial Guinea

Equatorial Guinea

Equatorial Guinea, officially the Republic of Equatorial Guinea where the capital Malabo is situated.Annobón is the southernmost island of Equatorial Guinea and is situated just south of the equator. Bioko island is the northernmost point of Equatorial Guinea. Between the two islands and to the...

; further, P. vivax infections were found both in humans and mosquitoes, which means that active transmission is occurring. This finding reinforces the idea that this parasite is able to use receptors other than Duffy to invade erythrocytes, which may have an enormous impact in P. vivax current distribution. Because of these several reports from different parts of the world it is clear that some variants of P.vivax are being transmitted to humans who are not expressing DARC on their red cells. The frequency of such transmission is still unknown. Identification of the parasite and host molecules that allow Duffy-independent invasion of human erythrocytes is an important task for the future, because it may facilitate vaccine

Vaccine

A vaccine is a biological preparation that improves immunity to a particular disease. A vaccine typically contains an agent that resembles a disease-causing microorganism, and is often made from weakened or killed forms of the microbe or its toxins...

development.

P. vivax is clearly a less potent agent of natural selection that is P. falciparum. However, the morbidity of P. vivax is not negligible. For example, P. vivax infections induce a greater inflammatory response

Inflammation