Chiricahua

Encyclopedia

Apache

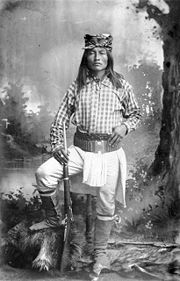

Apache is the collective term for several culturally related groups of Native Americans in the United States originally from the Southwest United States. These indigenous peoples of North America speak a Southern Athabaskan language, which is related linguistically to the languages of Athabaskan...

Native Americans who live in the Southwest United States. At the time of European encounter, they were living in 15 million acres (61,000 km2) of territory in southwestern New Mexico

New Mexico

New Mexico is a state located in the southwest and western regions of the United States. New Mexico is also usually considered one of the Mountain States. With a population density of 16 per square mile, New Mexico is the sixth-most sparsely inhabited U.S...

and southeastern Arizona

Arizona

Arizona ; is a state located in the southwestern region of the United States. It is also part of the western United States and the mountain west. The capital and largest city is Phoenix...

in the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

, and in northern Sonora

Sonora

Sonora officially Estado Libre y Soberano de Sonora is one of the 31 states which, with the Federal District, comprise the 32 Federal Entities of Mexico. It is divided into 72 municipalities; the capital city is Hermosillo....

and Chihuahua in Mexico

Mexico

The United Mexican States , commonly known as Mexico , is a federal constitutional republic in North America. It is bordered on the north by the United States; on the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; on the southeast by Guatemala, Belize, and the Caribbean Sea; and on the east by the Gulf of...

. Today two branches of the tribe are federally recognized as independent units: the Fort Sill Apache Tribe

Fort Sill Apache Tribe

The Fort Sill Apache Tribe is the federally recognized Native American tribe of Chiricahua Warm Springs Apache in Oklahoma.-History:The Fort Sill Apache Tribe is composed of Chiricahua Apache. The Apache are southern Athabaskan-speaking peoples who migrated many centuries ago from the subarctic to...

, located near Apache, Oklahoma

Apache, Oklahoma

Apache is a town in Caddo County, Oklahoma, USA. The population was 1,616 at the 2000 census.- Geography :Apache is located at ....

; and the Chiricahua tribe located on the Mescalero

Mescalero

Mescalero is an Apache tribe of Southern Athabaskan Native Americans. The tribe is federally recognized as the Mescalero Apache Tribe of the Mescalero Apache Reservation in southcentral New Mexico...

Apache reservation near Ruidoso, New Mexico

Ruidoso, New Mexico

Ruidoso is a village in Lincoln County, New Mexico, United States, adjacent to the Lincoln National Forest. The population was 8,029 at the 2010 census...

.

Name

The Chiricahua Apache are also known as the Chiricagui, Apaches de Chiricahui, Chiricahues, Chilicague, Chilecagez, and Chiricagua. The White Mountain Apache, including the Cibecue and Bylas groups of the Western ApacheWestern Apache

Western Apache refers to the Apache peoples living today primarily in east central Arizona. Most live within reservations. The White Mountain Apache of the Fort Apache, San Carlos, Yavapai-Apache, Tonto Apache, and the Fort McDowell Mohave-Apache Indian reservations are home to the majority of...

, called them Ha’i’ą́há (meaning 'Eastern Sunrise"). The San Carlos Apache called them Hák’ą́yé. The Navajo

Navajo people

The Navajo of the Southwestern United States are the largest single federally recognized tribe of the United States of America. The Navajo Nation has 300,048 enrolled tribal members. The Navajo Nation constitutes an independent governmental body which manages the Navajo Indian reservation in the...

, a group distinct from the Western Apache although related in language, call the Chiricahua Chíshí.

History

Cochise

Cochise was a chief of the Chokonen band of the Chiricahua Apache and the leader of an uprising that began in 1861. Cochise County, Arizona is named after him.-Biography:...

(whose name was derived from the Apache word Cheis, meaning "having the quality of oak"); Mangas Coloradas

Mangas Coloradas

Mangas Coloradas, or Dasoda-hae , was an Apache tribal chief and a member of the Eastern Chiricahua nation, whose homeland stretched west from the Rio Grande to include most of what is present-day southwestern New Mexico...

, Victorio

Victorio

Victorio was a warrior and chief of the Chihenne band of the Chiricahua Apaches in what is now the American states of New Mexico, Arizona, Texas and the Mexican states of Sonora and Chihuahua....

, Nana

Nana (Apache)

Kas-tziden or Haškɛnadɨltla , more widely known by his mexican-spanish appellation Nana , was a warrior and chief of the Chihenne band of the Chiricahua Apache...

, Juh

Juh

Juh was a warrior and leader of the Janeros local group of the Ndéndai band of the Chiricahua Apache. Prior to the 1870s, Juh was unknown in the areas controlled by the United States...

. Later they were led by Goyaałé

Geronimo

Geronimo was a prominent Native American leader of the Chiricahua Apache who fought against Mexico and the United States for their expansion into Apache tribal lands for several decades during the Apache Wars. Allegedly, "Geronimo" was the name given to him during a Mexican incident...

(known to the Americans as Geronimo) and Cochise's son Naiche

Naiche

Chief Naiche was the final hereditary chief of the Chiricahua band of Apache Indians.-Background:Naiche name, which in English means "meddlesome one" or "mischief maker", is alternately spelled Nache, Nachi, or Natchez. He was the youngest son of Cochise and was named after his grandmother...

. His Apache group was the last to continue to resist U.S. government control of the American Southwest.

Several loosely affiliated bands of Apache came to be known as the Chiricahua. These included the Chokonen, Chihenne, Nednai and the Bedonkohe. Today, all are commonly referred to as Chiricahua, but they were not historically a single band.

Many other bands and groups of Apachean language-speakers ranged over eastern Arizona and the American Southwest. The bands that are grouped under the Chiricahua term today had much history together: they intermarried and lived alongside each other, and they also occasionally fought with each other. They formed short-term as well as longer alliances that have caused scholars to classify them as one people.

The Apachean groups and the Navajo peoples were part of the Athabaskan migration into the North American continent from Asia, across the Bering Strait

Bering Strait

The Bering Strait , known to natives as Imakpik, is a sea strait between Cape Dezhnev, Chukotka Autonomous Okrug, Russia, the easternmost point of the Asian continent and Cape Prince of Wales, Alaska, USA, the westernmost point of the North American continent, with latitude of about 65°40'N,...

from Siberia

Siberia

Siberia is an extensive region constituting almost all of Northern Asia. Comprising the central and eastern portion of the Russian Federation, it was part of the Soviet Union from its beginning, as its predecessor states, the Tsardom of Russia and the Russian Empire, conquered it during the 16th...

. As the people moved south and east into North America, groups splintered off and became differentiated by language and culture over time. Some anthropologists believe that the Apache

Apache

Apache is the collective term for several culturally related groups of Native Americans in the United States originally from the Southwest United States. These indigenous peoples of North America speak a Southern Athabaskan language, which is related linguistically to the languages of Athabaskan...

and the Navajo

Navajo people

The Navajo of the Southwestern United States are the largest single federally recognized tribe of the United States of America. The Navajo Nation has 300,048 enrolled tribal members. The Navajo Nation constitutes an independent governmental body which manages the Navajo Indian reservation in the...

were pushed south and west into what is now New Mexico and Arizona by pressure from other Great Plains

Great Plains

The Great Plains are a broad expanse of flat land, much of it covered in prairie, steppe and grassland, which lies west of the Mississippi River and east of the Rocky Mountains in the United States and Canada. This area covers parts of the U.S...

Indians, such as the Comanche

Comanche

The Comanche are a Native American ethnic group whose historic range consisted of present-day eastern New Mexico, southern Colorado, northeastern Arizona, southern Kansas, all of Oklahoma, and most of northwest Texas. Historically, the Comanches were hunter-gatherers, with a typical Plains Indian...

and Kiowa

Kiowa

The Kiowa are a nation of American Indians and indigenous people of the Great Plains. They migrated from the northern plains to the southern plains in the late 17th century. In 1867, the Kiowa moved to a reservation in southwestern Oklahoma...

. Among the last of such splits were those that resulted in the formation of the different Apachean bands whom the later Europeans encountered: the southwestern Apache groups and the Navajo. Although both speaking forms of Southern Athabaskan, the Navajo and Apache have become culturally distinct.

From the beginning of EuropeanAmerican/Apache relations, there was conflict between them, as they competed for land and other resources, and had very different cultures. Their encounters were preceded by more than 100 years of Spanish colonial and Mexican incursions and settlement on the Apache lands. The United States settlers were newcomers to the competition for land and resources in the Southwest

Southwestern United States

The Southwestern United States is a region defined in different ways by different sources. Broad definitions include nearly a quarter of the United States, including Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Texas and Utah...

, but they inherited its complex history, and brought their own attitudes with them about American Indians and how to use the land. By the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo is the peace treaty, largely dictated by the United States to the interim government of a militarily occupied Mexico City, that ended the Mexican-American War on February 2, 1848...

, the US took on the responsibility to prevent and punish cross-border incursions by Apache who were raiding in Mexico.

The Apache viewed the United States colonists with ambivalence, and in some cases, enlisted them as allies in the early years against the Mexicans. In 1852, the US and some of the Chiricahua signed a treaty, but it had little lasting effect. During the 1850s, American miners and settlers began moving into Chiricahua territory, beginning encroachment that has been renewed in the migration to the Southwest of the previous two decades.

This forced the Apachean people to change their lives as nomads, free on the land. The US Army defeated them and forced them into the confinement of reservation life, on lands ill-suited for subsistence farming, which the US proffered as the model of civilization. Today, the Chiricahua are preserving their culture as much as possible, while forging new relationships with the peoples around them. The Chiricahua are a living and vibrant culture, a part of the greater American whole and yet distinct based on their history and culture.

Although they had lived peaceably with most Americans in the New Mexico Territory

New Mexico Territory

thumb|right|240px|Proposed boundaries for State of New Mexico, 1850The Territory of New Mexico was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from September 9, 1850, until January 6, 1912, when the final extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of...

up to about 1860, the Chiricahua became increasingly hostile to American encroachment in the Southwest after a number of provocations had occurred between them. In 1835, Mexico had placed a bounty on Apache scalps which further inflamed the situation. In 1837, the American John (aka James) Johnson invited the Chihenne in the area to trade with his party (near the mines at Santa Rita del Cobre, New Mexico). When they gathered around a blanket on which pinole (a ground corn flour) had been placed for them, Johnson and his men opened fire on the Chihenne with rifles and a concealed cannon loaded with scrap iron, glass, and a length of chain). They killed about 20 Apache, including the chief Juan José Compá. Mangas Coloradas is said to have witnessed this attack, which inflamed his and other Apache warriors' desires for vengeance for many years. The historian Rex W. Strickland argued that the Apache had come to the meeting with their own intentions of attacking Johnson's party, but were taken by surprise.

After the conclusion of the US/Mexican War and the Gadsden Purchase

Gadsden Purchase

The Gadsden Purchase is a region of present-day southern Arizona and southwestern New Mexico that was purchased by the United States in a treaty signed by James Gadsden, the American ambassador to Mexico at the time, on December 30, 1853. It was then ratified, with changes, by the U.S...

in the late 1840s, Americans began to enter the territory in greater numbers. This increased the opportunities for incidents and misunderstandings. In 1851, miners tied Mangas Coloradas

Mangas Coloradas

Mangas Coloradas, or Dasoda-hae , was an Apache tribal chief and a member of the Eastern Chiricahua nation, whose homeland stretched west from the Rio Grande to include most of what is present-day southwestern New Mexico...

to a tree and whipped him after he tried to convince them to move away from the Pinos Altos, New Mexico

Pinos Altos, New Mexico

Pinos Altos, in Grant County, New Mexico, was a mining town, formed in 1860 following the discovery of gold in the nearby Pinos Altos Mountains. The town site is located about five to ten miles north of the present day Silver City, New Mexico...

area he loved. His followers and related Chiricahua bands were incensed by the treatment of their respected chief. Mangas had been just as great a chief in his prime (during the 1830s and 1840s) as Cochise was then becoming.

A few years later, in 1861 the US Army killed some of Cochise’s relatives near Apache Pass

Apache Pass

Apache Pass is a historic passage in the U.S. state of Arizona between the Dos Cabezas Mountains and Chiricahua Mountains, approximately 32 km E-SE of Willcox, Arizona.-Apache Spring:...

, in what became known as the Bascom Affair

Bascom Affair

The Bascom Affair is considered to be the key event in triggering the 1860s Apache War. The Apache Wars were fought during the nineteenth century between the U.S. military and many tribes in what is now the southwestern United States...

. The Chiricahua called the incident "cut the tent." In 1863, American soldiers killed Mangas Colorados as he entered their camp to negotiate a peace. His body was mutilated by the soldiers, and his people were enraged by his murder. The Chiricahua began to consider the Americans as "enemies we go against them." From that time, they waged almost constant war against US settlers and the Army for the next 23 years.

In 1872, General Oliver O. Howard

Oliver O. Howard

Oliver Otis Howard was a career United States Army officer and a Union general in the American Civil War...

, with the help of Thomas Jeffords, succeeded in negotiating a peace with Cochise

Cochise

Cochise was a chief of the Chokonen band of the Chiricahua Apache and the leader of an uprising that began in 1861. Cochise County, Arizona is named after him.-Biography:...

. The US established a Chiricahua Apache Reservation with Jeffords as US Agent, near Fort Bowie

Fort Bowie

Fort Bowie was a 19th century outpost of the United States Army located in southeastern Arizona near the present day town of Willcox, Arizona.Fort Bowie was established in 1862 after a series of engagements between the U.S. Military and the Chiricahua Apaches. The most violent of which was the...

, Arizona Territory. It remained open for about 4 years, during which the chief Cochise died (from natural causes). In 1877, about three years after Cochise's death, the US moved the Chiricahua and some other Apache bands to the San Carlos Apache Indian Reservation

San Carlos Apache Indian Reservation

The San Carlos Apache Indian Reservation, in southeastern Arizona, United States, was established in 1871 as a reservation for the Chiricahua Apache tribe. It was referred to by some as "Hell's Forty Acres," due to a myriad of dismal health and environmental conditions.-Formation:President U.S....

, still in Arizona.

The mountain people hated the desert environment of San Carlos, and some frequently began to leave the reservation and sometimes raid neighboring settlers. They surrendered to General Nelson Miles in 1886. The most well-known warrior leader of the renegades, although he was not considered a chief', was the forceful and influential Geronimo

Geronimo

Geronimo was a prominent Native American leader of the Chiricahua Apache who fought against Mexico and the United States for their expansion into Apache tribal lands for several decades during the Apache Wars. Allegedly, "Geronimo" was the name given to him during a Mexican incident...

. He and Naiche

Naiche

Chief Naiche was the final hereditary chief of the Chiricahua band of Apache Indians.-Background:Naiche name, which in English means "meddlesome one" or "mischief maker", is alternately spelled Nache, Nachi, or Natchez. He was the youngest son of Cochise and was named after his grandmother...

(the hereditary leader and son of Cochise) together led many of the resisters during those last few years of freedom.

They made a stronghold in the Chiricahua Mountains

Chiricahua Mountains

The Chiricahua Mountains are a mountain range in southeastern Arizona which are part of the Basin and Range province of the southwest, and part of the Coronado National Forest...

, part of which is now inside Chiricahua National Monument

Chiricahua National Monument

Chiricahua National Monument is a unit of the National Park Service located in the Chiricahua Mountains. It is famous for its extensive vertical rock formations. The monument is located approximately southeast of Willcox, Arizona. It preserves the remains of an immense volcanic eruption that...

, and across the intervening Willcox Playa

Willcox Playa

The Willcox Playa is a large endorheic dry lake or sink in Cochise County. It is located south of and adjacent to Willcox, Arizona, in the Sonoran Desert ecoregion. It is the remnant of Pleistocene pluvial Lake Cochise...

to the northeast, in the Dragoon Mountains

Dragoon Mountains

Dragoon Mountains are a range of mountains located in Cochise County, Arizona. The range is about 25 mi long, running on an axis extending south-south east through Willcox.- Geography :...

(all in southeastern Arizona). In late frontier times, the Chiricahua ranged from San Carlos and the White Mountains of Arizona, to the adjacent mountains of southwestern New Mexico around what is now Silver City, and down into the mountain sanctuaries of the Sierra Madre (of northern Mexico). There they often joined with their Nednai Apache kin.

General George Crook

George Crook

George R. Crook was a career United States Army officer, most noted for his distinguished service during the American Civil War and the Indian Wars.-Early life:...

, then General Miles' troops, aided by Apache scouts from other groups, pursued the exiles until they gave up. Mexico and the United States had negotiated an agreement allowing their troops in pursuit of the Apache to continue into each other's territories. This prevented the Chiricahua groups from using the border as a shield; as they could gain little time to rest and consider their next move, the fatigue, attrition and demoralization of the constant hunt led to their surrender.

The final 34 hold-outs, including Geronimo and Naiche, surrendered to units of General Miles' forces in September 1886. From Bowie Station, Arizona, they were entrained, along with most of the other remaining Chiricahua (as well as the Army's Apache scouts), and exiled to Fort Marion, Florida

Florida

Florida is a state in the southeastern United States, located on the nation's Atlantic and Gulf coasts. It is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the north by Alabama and Georgia and to the east by the Atlantic Ocean. With a population of 18,801,310 as measured by the 2010 census, it...

. At least two Apache warriors, Massai

Massai

Massai was a member of the Mimbres band of Chiricahua Apache. He was warrior who escaped from a train that was sending the scouts and renegades to Florida to be held with Geronimo and Chihuahua.Born to White Cloud and Little Star at Mescal Mountain, Arizona, near Globe...

and Gray Lizard, escaped from their prison car and made their way back to Arizona in a 1200 miles (1,931.2 km) journey to their ancestral lands.

After a number of deaths of Chiricahua at the Fort Marion prison near St. Augustine, Florida

St. Augustine, Florida

St. Augustine is a city in the northeast section of Florida and the county seat of St. Johns County, Florida, United States. Founded in 1565 by Spanish explorer and admiral Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, it is the oldest continuously occupied European-established city and port in the continental United...

, the survivors were moved, first to Alabama

Alabama

Alabama is a state located in the southeastern region of the United States. It is bordered by Tennessee to the north, Georgia to the east, Florida and the Gulf of Mexico to the south, and Mississippi to the west. Alabama ranks 30th in total land area and ranks second in the size of its inland...

, and later to Fort Sill, Oklahoma. Geronimo's surrender ended the Indian Wars in the United States. A group of Chiricahua (aka the Nameless Ones or Bronco Apache) who were not captured by U.S. forces refused to surrender. They escaped over the border to Mexico, and settled in the remote Sierra Madre

Sierra Madre Occidental

The Sierra Madre Occidental is a mountain range in western Mexico.-Setting:The range runs north to south, from just south of the Sonora–Arizona border southeast through eastern Sonora, western Chihuahua, Sinaloa, Durango, Zacatecas, Nayarit, Jalisco, Aguascalientes to Guanajuato, where it joins...

mountains.

Eventually, the surviving Chiricahua prisoners were moved to the Fort Sill

Fort Sill

Fort Sill is a United States Army post near Lawton, Oklahoma, about 85 miles southwest of Oklahoma City.Today, Fort Sill remains the only active Army installation of all the forts on the South Plains built during the Indian Wars...

military reservation in Oklahoma. In August 1912, by an act of the U.S. Congress, they were released from their prisoner of war status after they were thought to be no further threat. Although promised land at Fort Sill, they met resistance from local non-Apache. They were given the choice to remain at Fort Sill or to relocate to the Mescalero reservation near Ruidoso, New Mexico. Two-thirds of the group, 183 people, elected to go to New Mexico, while 78 remained in Oklahoma. Their descendants still reside in these places. At the time, they were not permitted to return to Arizona because of hostility from the long wars.

Bands

Opata language

Ópata is the name of the Uto-Aztecan language spoken by the Opata people of northern central Sonora in Mexico...

word Chiguicagui (‘mountain of the wild turkey’).

According to Morris E. Opler (1941), the Chiricahuas consisted of three bands:

- Chíhéne or Chííhénee’ 'Red Paint People' (also known as the Eastern Chiricahua, Warm Springs Apache, Gileños, Ojo Caliente Apache, Coppermine Apache, Copper Mine, Mimbreños, Mimbres, Mogollones, Tcihende),

- Ch’úk’ánéń or Ch’uuk’anén (also known as the Central Chiricahua, Ch’ók’ánéń, Cochise Apache, Chiricahua proper, Chiricaguis, Tcokanene), or the Sunrise People;

- Ndé’indaaí or Nédnaa’í 'Enemy People' (http://www.fortsillapache-nsn.gov/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=5&Itemid=6also known as the Southern Chiricahua, Chiricahua proper, Pinery Apache, Ne’na’i), or "those ahead at the end".

Schroeder (1947) lists five bands:

- Mogollon

- Copper Mine

- Mimbres

- Warm Spring

- Chiricahua proper

The Chiricahua-Warm Springs Fort Sill Apache tribe

Fort Sill Apache Tribe

The Fort Sill Apache Tribe is the federally recognized Native American tribe of Chiricahua Warm Springs Apache in Oklahoma.-History:The Fort Sill Apache Tribe is composed of Chiricahua Apache. The Apache are southern Athabaskan-speaking peoples who migrated many centuries ago from the subarctic to...

in Oklahoma say they have four bands in Fort Sill:

- Chíhéne (also known as the Warm Springs band, Chinde),

- Chukunen (also known as the Chiricahua band, Chokonende),

- Bidánku (also known as Bidanku, Bedonkohe (?), Bronco),

- Ndéndai (also known as Ndénai, Nednai).

Today they use the word Chidikáágu (derived from the Spanish word Chiricahua) to refer to the Chiricahua in general, and the word Indé, to refer to the Apache in general.

Other sources list these and additional bands:

- Chokonen (Chu-ku-nde - ‘Ridge of the Mountainside People’, proper or Central Chiricahua)

- Chokonen (lived west of SaffordSaffordSafford may refer to :* Safford, Arizona* Safford, Alabama, an unincorporated community in Dallas County, Alabama* Safford House, a historic home in Tarpon Springs, Florida* Safford Cape , American composer and musicologist...

, Arizona, along the upper reaches of the Gila RiverGila RiverThe Gila River is a tributary of the Colorado River, 650 miles long, in the southwestern states of New Mexico and Arizona.-Description:...

, along the San Francisco RiverSan Francisco RiverThe San Francisco River is a river in the southwest United States, the largest tributary of the Upper Gila River. The river originates in Arizona and flows into New Mexico before it curves around and enters the Gila down stream from Clifton, Arizona....

in the north to the Mogollon MountainsMogollon MountainsThe Mogollon Mountains or Mogollon Range are a mountain range east of the San Francisco River in Grant and Catron counties of southwestern New Mexico, between the communities of Reserve and Silver City. They extend roughly north-south for about 30 miles , and form part of the divide between the...

in New Mexico in the east and the San Simon ValleySan Simon ValleyThe San Simon Valley is a broad valley east of the Chiricahua Mountains, in the northeast corner of Cochise County, Arizona and southeastern Graham County, with a small portion near Antelope Pass in Hidalgo County of southwestern New Mexico. The valley trends generally north-south but in its...

to the southwest, northeastern local group) - Chihuicahui (lived in SE Arizona in the Huachuca MountainsHuachuca MountainsThe Huachuca Mountain range is part of the Sierra Vista Ranger District of the Coronado National Forest. The Huachuca Mountains are located in Cochise County, Arizona approximately south-southeast of Tucson and southwest of the city of Sierra Vista, Arizona...

west of the San Pedro RiverSan Pedro River (Arizona)San Pedro River is a northward-flowing stream originating about ten miles south of Sierra Vista, Arizona near Cananea, Sonora, Mexico. It is one of only two rivers which flow north from Mexico into the United States. The river flows north through Cochise County, Pima County, Graham County, and...

, in the northwest along a line of today's BensonBenson, Arizona-Transportation:Benson Airport is located 3 miles north west of the city.Benson is served by Interstate 10 to the north, which travels directly to downtown Tucson....

, Johnson, WillcoxWillcox, ArizonaWillcox is a city in Cochise County, Arizona, United States. According to 2006 Census Bureau estimates, the population of the city is 3,769. Professional wrestler Ted Dibiase lived his formative years in Willcox, as did singer Tanya Tucker.-History:...

, and north along the San Simon River to east of SW New Mexico, controlled the southern PinalenoPinaleno MountainsThe Pinaleño Mountains, or the Pinal Mountains, are a remote mountain range in southeastern Arizona. They have over of vertical relief, more than any other range in the state. The mountains are surrounded by the Sonoran-Chihuahuan Desert. Subalpine forests cover the higher elevations...

, Winchester, Dos CabezasDos Cabezas MountainsThe Dos Cabezas Mountains are a mountain range in southeasternmost Arizona, USA. The Dos Cabezas Mountains Wilderness lies east of Willcox, Arizona and south of Bowie, Arizona in Cochise County...

, ChiricahuaChiricahua MountainsThe Chiricahua Mountains are a mountain range in southeastern Arizona which are part of the Basin and Range province of the southwest, and part of the Coronado National Forest...

, DragoonDragoon MountainsDragoon Mountains are a range of mountains located in Cochise County, Arizona. The range is about 25 mi long, running on an axis extending south-south east through Willcox.- Geography :...

and Mule MountainsMule MountainsThe Mule Mountains are a north/south running mountain range located in the south-central area of Cochise County, Arizona. The highest peak, Mount Ballard, rises to...

, southwestern local group) - Dzilmora (lived in the Alamo HuecoAlamo Hueco MountainsThe Alamo Hueco Mountains are a 15 mile long, mountain range in southeast Hidalgo County, New Mexico, adjacent the border of Chihuahua state, Mexico. The range lies near the southern end of the mountains bordering the extensive north-south Playas Valley; the Little Hatchet and Big Hatchet...

, Little HatchetHachita ValleyThe Hachita Valley, , is a small valley in southwest New Mexico. The valley is in the east of the New Mexico Bootheel region and borders Chihuahua state, Mexico...

and Big Hatchet MountainsBig Hatchet MountainsThe Big Hatchet Mountains are an 18 mi long, mountain range in southeast Hidalgo County, New Mexico, adjacent the northern border of Chihuahua state, Mexico....

in SW New Mexico, southeastern local group) - Animas (lived south of the Rio Gila, and west of the San Simon Valley in the PeloncilloPeloncillo Mountains (Cochise County)The Peloncillo Mountains of Cochise County, , is a mountain range in northeast Cochise County, Arizona. A northern north-south stretch of the range extends to the southern region of Greenlee County on the northeast, and a southeast region of Graham County on the northwest...

MountainsPeloncillo Mountains (Hidalgo County)The Peloncillo Mountains of Hidalgo County, , is a major 35-mi long mountain range of southwest New Mexico's Hidalgo County, and also part of the New Mexico Bootheel region. The range continues to the northwest into Arizona as the Peloncillo Mountains of Cochise County, Arizona...

along the Arizona-New Mexico border south to the Guadalupe Canyon and eastward in the Animas ValleyAnimas ValleyThe Animas Valley is a lengthy and narrow, north-south 85 mi long, valley located in western Hidalgo County, New Mexico in the Bootheel Region; the extreme south of the valley lies in Chihuahua, in the northwest of the Chihuahuan Desert, the large desert region of the north-central Mexican...

and Animas MountainsAnimas MountainsThe Animas Mountains are a small mountain range in Hidalgo County, within the "Boot-Heel" region of far southwestern New Mexico, in the United States. They extend north-south for about 30 miles along the Continental Divide, from near the town of Animas to a few miles north of the border with...

in SW New Mexico, southern local group) - local group (lived in NE Sonora and adjacent Arizona, in Guadalupe Canyon, along the San Bernardino RiverSan Bernardino RiverThe Rio San Bernardino, or San Bernardino River, begins in extreme southeastern Cochise County, Arizona and is a tributary of the Bavispe River, in Sonora, Mexico. It is named after one of Southern California's largest cities, San Bernardino.-Watershed:...

, northwestern parts of the Sierra San LuisSierra San LuisThe Sierra San Luis range is a mountain range in northwest Chihuahua, northeast Sonora, Mexico at the northern region of the Sierra Madre Occidental cordillera...

, in the Batepito Valley with the Sierra Pitaycachi, east of FronterasFronterasFronteras is the seat of Fronteras Municipality in the northeast of the Mexican state of Sonora. The elevation is 1,120 meters and neighboring municipalities are Agua Prieta, Nacozari and Bacoachi. The area is 2839.62 km², which represents 1.53% of the state total.-Geography:Fronteras is located...

, as their stronghold) - local group (lived east of Fronteras in der Sierra Pilares de Teras in Sonora)

- local group (lived in the Sierra de los Ajos northeast of the Sonora RiverSonora RiverRío Sonora is a 402-kilometer-long river of Mexico. It lies on the Pacific slope of the Mexican state of Sonora and it runs into the Gulf of California.-Watershed:...

, along the Bavispe RiverBavispe RiverThe Rio Bavispe or Bavispe River is a river in Mexico which flows briefly north then mainly south by southwest until it joins with the Aros River to become the Yaqui River, eventually joining the Gulf of California.-History:...

towards Fronteras in the north)

- Chokonen (lived west of Safford

- Bedonkohe (Bi-dan-ku - ‘In Front of the End People’, Bi-da-a-naka-enda - ‘Standing in front of the enemy’, often called Mogollon, Gila Apaches, Northeastern Chiricahua, lived in the Mogollon MountainsMogollon MountainsThe Mogollon Mountains or Mogollon Range are a mountain range east of the San Francisco River in Grant and Catron counties of southwestern New Mexico, between the communities of Reserve and Silver City. They extend roughly north-south for about 30 miles , and form part of the divide between the...

and Tularosa Mountains between the San Francisco RiverSan Francisco RiverThe San Francisco River is a river in the southwest United States, the largest tributary of the Upper Gila River. The river originates in Arizona and flows into New Mexico before it curves around and enters the Gila down stream from Clifton, Arizona....

in the West and the Gila River to the southeast in west New Mexico) - Chihenne (Chi-he-nde - ‘Red Painted People’, often called Copper Mine, Warm Springs, Mimbres, Gila Apaches, Eastern Chiricahua)

- Warm Springs (Spanish: Ojo Caliente - Hot Springs)

- northern Warm Springs (lived in the northeast of the Bedonkohe in the Datil, MagdalenaMagdalena MountainsThe Magdalena Mountains are a small in area, but regionally high, mountain range in Socorro County, in west-central New Mexico in the southwestern United States. The highest point in the range is South Baldy, at 10,783 ft . The range runs roughly north-south and is about 18 miles long...

and Socorro Mountains, the Plains of San Agustin, and from today's QuemadoQuemado, New MexicoQuemado is an unincorporated community in Catron County, New Mexico, United States. Walter De Maria's 1977 art installation, The Lightning Field, is between Quemado and Pie Town, New Mexico....

east toward the Rio GrandeRio GrandeThe Rio Grande is a river that flows from southwestern Colorado in the United States to the Gulf of Mexico. Along the way it forms part of the Mexico – United States border. Its length varies as its course changes...

, northern local group) - southern Warm Springs (Warm Springs proper, settled around Ojo CalienteOjo Caliente, New MexicoOjo Caliente is a small unincorporated community in Taos County, New Mexico, United States. It lies along U.S. Route 285 near the Rio Grande. The state capital, Santa Fe lies south of Ojo Caliente, which sits between Espanola and Taos, approximately 50 miles southeast of Ghost Ranch. The community...

near the present-day Monticello, between the Cuchillo Negro Creek and the Animas Creek, controlled the San MateoSan Mateo MountainsThe San Mateo Mountains may refer to:* San Mateo Mountains * San Mateo Mountains in Cibola and McKinley counties in New Mexico, which includes Mount Taylor* San Mateo Mesa...

and Negretta Mountains as well as the Black RangeBlack RangeThe Black Range is an igneous mountain range running north-south in Sierra and Grant counties in west-central New Mexico, in the southwestern United States. Its central ridge forms the western and eastern borders, respectively, of the two counties through much of their contact...

west of the Rio Grande to the Rio Gila, used the hot springsHot SpringsHot Springs may refer to:* Hot Springs, Arkansas** Hot Springs National Park, Arkansas*Hot Springs, California**Hot Springs, Lassen County, California**Hot Springs, Modoc County, California**Hot Springs, Placer County, California...

around the vicinity of Truth or ConsequencesTruth or ConsequencesTruth or Consequences is an American quiz show originally hosted on NBC radio by Ralph Edwards and later on television by Edwards , Jack Bailey , Bob Barker , Bob Hilton and Larry Anderson . The television show ran on CBS, NBC and also in syndication...

- hence called Warm Springs or Ojo Caliente Apaches, southern local group)

- northern Warm Springs (lived in the northeast of the Bedonkohe in the Datil, Magdalena

- Gila / Gileños

- Copper Mines (lived southwest of the Gila River, centered around the Santa Lucia Springs in the Little BurroLittle Burro MountainsThe Little Burro Mountains are a short 15 mi long, mountain range located in Grant County, New Mexico. The range lies adjacent to the southeast border of the larger Big Burro Mountains. The Little Burro Mountains are located 8 mi southwest of Silver City...

and Big Burro MountainsBig Burro MountainsThe Big Burro Mountains are a moderate length 35 mile long, mountain range located in central Grant County, New Mexico. The range's northwest-southeast 'ridgeline' is located 15 mi southwest of Silver City....

, controlled the Pinos Altos Mountains, Pyramid MountainsPyramid MountainsThe Pyramid Mountains are a 30 mi long, mountain range in central-east Hidalgo County, New Mexico. The city of Lordsburg is at its northern border, where the range causes Interstate 10 to traverse northeast, then southeast around the range....

and the vicinity of Santa Rita del Cobre along the Mimbres River in the east - hence called Copper Mine Apaches, western local group) - Mimbres /Mimbreños (lived in southeast-central New Mexico, between the Mimbres RiverMimbres RiverThe Mimbres River is a river in southwestern New Mexico. It forms from snow pack and runoff on the south-western slopes of the Black Range and flows into a small endorheic basin east of Deming, New Mexico. The uplands watershed are administered by the US Forest Service, while the land in the...

and the Rio Grande up in the Mimbres Mountains and the Cook's Range - hence called Mimbres Apaches, eastern local group) - local group (lived in southern New Mexico in the Pyramid MountainsPyramid MountainsThe Pyramid Mountains are a 30 mi long, mountain range in central-east Hidalgo County, New Mexico. The city of Lordsburg is at its northern border, where the range causes Interstate 10 to traverse northeast, then southeast around the range....

and Florida MountainsFlorida MountainsThe Florida Mountains are a small 12-mi long, mountain range in New Mexico. The mountains lie in southern Luna County about 15 mi southeast of Deming, and 20 mi north of Chihuahua state, Mexico; the range lies in the north of the Chihuahuan Desert region, and extreme southwestern New...

(called by the Chihenne Dzlnokone - Long Hanging Mountain) moved to the Rio Grande in the east and south to the Mexican border, southern local group)

- Copper Mines (lived southwest of the Gila River, centered around the Santa Lucia Springs in the Little Burro

- Warm Springs (Spanish: Ojo Caliente - Hot Springs)

- Nednhi (Ndé'ndai - ‘Enemy People’, ‘People who make trouble’, often called Bronco Apaches, Sierre Madre Apaches,Southern Chiricahua)

- Janeros (lived in NW Chihuahua, SE Arizona and NE Sonora in the Animas Mountains, Florida Mountains, south into the Sierra San LuisSierra San LuisThe Sierra San Luis range is a mountain range in northwest Chihuahua, northeast Sonora, Mexico at the northern region of the Sierra Madre Occidental cordillera...

, Sierra del TigreSierra del TigreSierra del Tigre is a mountain range in northeastern Sonora, Mexico at the northern region of the Sierra Madre Occidental. The region contains sky island mountain ranges, called the Madrean Sky Islands, some separated from the Sierra Madre Occidental proper, and occurring in the northeastern...

, Sierra de Carcay, Sierra de Boca Grande, west beyond the Aros River to Bavispe, east along the Janos River and Casas Grandes RiverCasas Grandes River-References:*Atlas of Mexico, 1975 .*The Prentice Hall American World Atlas, 1984.*Rand McNally, The New International Atlas, 1993....

toward the Lake Guzmán in the northern part of the Guzmán BasinGuzmán BasinThe Guzmán Basin is an endorheic basin of northern Mexico and the southwestern United States. It occupies the northwestern portion of Chihuahua in Mexico, and extends into southwestern New Mexico in the United States....

and traded at the presidio of JanosJanos, ChihuahuaJanos is a town located in the northern Mexican state of Chihuahua. It serves as the municipal seat of government for the surrounding Janos Municipality of the same name. The 2010 Mexican national census reported a population of 2,738 inhabitants....

, likely called Dzilthdaklizhéndé - ‘Blue Mountain People’, northern local group) - Carrizaleños (lived exclusively in Chihuahua, between the presidioPresidioA presidio is a fortified base established by the Spanish in North America between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries. The fortresses were built to protect against pirates, hostile native Americans and enemy colonists. Other presidios were held by Spain in the sixteenth and seventeenth...

s of Janos in the west and Carrizal and Lake Santa Maria in the east, south toward Corralitos, Casas GrandesCasas Grandes, ChihuahuaCasas Grandes is a town located in the northern Mexican state of Chihuahua. It serves as the municipal seat of government for the surrounding Casas Grandes Municipality of the same name....

and Agua Nuevas 60 miles (96.6 km) north of ChihuahuaChihuahua, ChihuahuaThe city of Chihuahua is the state capital of the Mexican state of Chihuahua. It has a population of about 825,327. The predominant activity is industry, including domestic heavy, light industries, consumer goods production, and to a smaller extent maquiladoras.-History:It has been said that the...

, controlled the southern part of the Guzmán Basin, and the mountains along the Casas Grandes, Santa MariaSanta Maria River (Chihuahua)-References:*Atlas of Mexico, 1975 .*The Prentice Hall American World Atlas, 1984.*Rand McNally, The New International Atlas, 1993....

and Carmen RiverCarmen River-References:*Atlas of Mexico, 1975 .*The Prentice Hall American World Atlas, 1984.*Rand McNally, The New International Atlas, 1993....

, likely called Tsebekinéndé - ‘Stone House People’ or ‘Rock House People’, southeastern local group) - Pinaleños (lived south of BavispeBavispeBavispe is a small town and a municipality in the northeast part of the Mexican state of Sonora.-Location:The municipality is located in the northeast of the state at . The elevation of the administrative seat is 902 meters above sea level...

, between the Bavispe River and Aros RiverAros River-References:*Atlas of Mexico, 1975 .*The Prentice Hall American World Atlas, 1984.*Rand McNally, The New International Atlas, 1993....

in NE Sonora and NW Chihuahua, controlled the Sierra Huachinera, Sierra de los Alisos and Sierra Nacori Chico, the mountains had a large stock of pine forest – hence they were called Pinery Apaches, southwestern local group).

- Janeros (lived in NW Chihuahua, SE Arizona and NE Sonora in the Animas Mountains, Florida Mountains, south into the Sierra San Luis

The Chokonen, Chihenne, Nednhi and Bedonkohe had probably up to three other local groups, named respectively after their leader or the area they inhabited. By the end of the 19th century, the surviving Apache no longer remembered such groups. They may have been annihilated (like the Pinaleño-Nednhi) or had joined more mighty local groups (the remnant of the Carrizaleños-Nedhni camped together with their northern kin, the Janero-Nednhi).

The Carrizaleňo-Nednhi shared overlapping territory in the surroundings of Casas Grandes and Agua Nuevas with the Tsebekinéndé, a southern Mescalero

Mescalero

Mescalero is an Apache tribe of Southern Athabaskan Native Americans. The tribe is federally recognized as the Mescalero Apache Tribe of the Mescalero Apache Reservation in southcentral New Mexico...

band (which was often called Aguas Nuevas by the Spanish). The Spanish referred to the Apache band by the same name of Tsebekinéndé. These two different Apache bands were often confused with each other. (Similar confusion arose over distinguishing the Janeros-Nednhi of the Chiricahua (Dzilthdaklizhéndé) and the Dzithinahndé of the Mescalero).

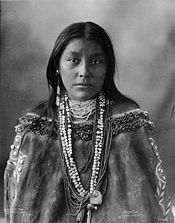

Notable Chiricahua Apache people

- Mildred CleghornMildred CleghornMildred Cleghorn was first chairperson of the Fort Sill Apache Tribe.Mildred Imoch Cleghorn, whose Apache names were Eh-Ohn and Lay-a-Bet, was one of the last Chiricahua Apaches born under a "prisoner of war" status. She was an educator and traditional doll maker, and was regarded as a cultural...

, first tribal chairperson at the Fort Sill Reservation, elected in 1976 - CochiseCochiseCochise was a chief of the Chokonen band of the Chiricahua Apache and the leader of an uprising that began in 1861. Cochise County, Arizona is named after him.-Biography:...

, warrior and chief - Mangas ColoradasMangas ColoradasMangas Coloradas, or Dasoda-hae , was an Apache tribal chief and a member of the Eastern Chiricahua nation, whose homeland stretched west from the Rio Grande to include most of what is present-day southwestern New Mexico...

, chief - DahtesteDahtesteDahteste was a Chiricahua Apache woman. Despite being married with children, she took part in raiding parties with her husband. She was a compatriot of Geronimo, and was instrumental in negotiating his surrender to the U.S. Cavalry. She spent 8 years in a Florida prison, and was later shipped to a...

, woman warrior - GeronimoGeronimoGeronimo was a prominent Native American leader of the Chiricahua Apache who fought against Mexico and the United States for their expansion into Apache tribal lands for several decades during the Apache Wars. Allegedly, "Geronimo" was the name given to him during a Mexican incident...

, warrior, medicine man - Bob HaozousBob HaozousBob Haozous is a Chiricahua Apache sculptor from Santa Fe, New Mexico. He is enrolled in the Fort Sill Apache Tribe.-Background:Bob Haozous was born on 1 April 1943 in Los Angeles, California. His parents are Anna Marie Gallegos, a Diné-Mestiza textile artist, and the late Allan Houser , a famous...

, sculptor - Allan HouserAllan HouserAllan Capron Houser or Haozous a Chiricahua Apache sculptor from Oklahoma. He was one of the most renowned Native American painters and Modernist sculptors of the 20th century....

, sculptor - JuhJuhJuh was a warrior and leader of the Janeros local group of the Ndéndai band of the Chiricahua Apache. Prior to the 1870s, Juh was unknown in the areas controlled by the United States...

, warrior and leader of the Ndéndai band - LozenLozenLozen was a skilled warrior and a prophet of the Chihenne Chiricahua Apache. She was the sister of Victorio, a prominent chief. Born into the Chihenne band during the late 1840s, Lozen was a skilled warrior and a prophet. According to legends, she was able to use her powers in battle to learn the...

, woman warrior - MassaiMassaiMassai was a member of the Mimbres band of Chiricahua Apache. He was warrior who escaped from a train that was sending the scouts and renegades to Florida to be held with Geronimo and Chihuahua.Born to White Cloud and Little Star at Mescal Mountain, Arizona, near Globe...

, warrior - NaicheNaicheChief Naiche was the final hereditary chief of the Chiricahua band of Apache Indians.-Background:Naiche name, which in English means "meddlesome one" or "mischief maker", is alternately spelled Nache, Nachi, or Natchez. He was the youngest son of Cochise and was named after his grandmother...

, chief and second son of Cochise - NanaNana (Apache)Kas-tziden or Haškɛnadɨltla , more widely known by his mexican-spanish appellation Nana , was a warrior and chief of the Chihenne band of the Chiricahua Apache...

, warrior - TazaChief TazaTaza was the son of Chiricahua Apache leader Cochise. He died September 26, 1876, after only about two years as chief. He is buried in Congressional Cemetery Washington D.C....

, chief and son of Cochise - VictorioVictorioVictorio was a warrior and chief of the Chihenne band of the Chiricahua Apaches in what is now the American states of New Mexico, Arizona, Texas and the Mexican states of Sonora and Chihuahua....

, chief

Cited works

- Debo, Angie. (1976) Geronimo: The Man, His Time, His Place. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-1828-8.

- Thrapp, Dan L. (1988) The Conquest of Apacheria. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-1286-7

External links

- Indian Nations Indian Territory Archives - Ft. Sill Apache

- Return of the Chiricahua Apache Nde Nation, Chiriahua Organization

- Fort Sill Apache Tribal Chairman Jeff Housers Website

- Chiricahua and Mescalero Apache Texts

- Allan Houser, Chiricahua Apache artist

- List of some Chiricaua warriors, probably from Thrapp's Biography