Cherokee history

Encyclopedia

Oral tradition

Oral tradition and oral lore is cultural material and traditions transmitted orally from one generation to another. The messages or testimony are verbally transmitted in speech or song and may take the form, for example, of folktales, sayings, ballads, songs, or chants...

s and written history of the Cherokee

Cherokee

The Cherokee are a Native American people historically settled in the Southeastern United States . Linguistically, they are part of the Iroquoian language family...

people, who are currently enrolled in the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians

Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians

The Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians , is a federally recognized Native American tribe in the United States of America, who are descended from Cherokee who remained in the Eastern United States while others moved, or were forced to relocate, to the west in the 19th century. The history of the...

, Cherokee Nation

Cherokee Nation

The Cherokee Nation is the largest of three Cherokee federally recognized tribes in the United States. It was established in the 20th century, and includes people descended from members of the old Cherokee Nation who relocated voluntarily from the Southeast to Indian Territory and Cherokees who...

, and United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians

United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians

The United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians in Oklahoma is a federally recognized tribe of Cherokee Indians headquartered in Tahlequah, Oklahoma. The United Keetoowah are also referred to as the UKB...

, living predominantly in North Carolina

North Carolina

North Carolina is a state located in the southeastern United States. The state borders South Carolina and Georgia to the south, Tennessee to the west and Virginia to the north. North Carolina contains 100 counties. Its capital is Raleigh, and its largest city is Charlotte...

and Oklahoma

Oklahoma

Oklahoma is a state located in the South Central region of the United States of America. With an estimated 3,751,351 residents as of the 2010 census and a land area of 68,667 square miles , Oklahoma is the 28th most populous and 20th-largest state...

.

Origins

Appalachia

Appalachia is a term used to describe a cultural region in the eastern United States that stretches from the Southern Tier of New York state to northern Alabama, Mississippi, and Georgia. While the Appalachian Mountains stretch from Belle Isle in Canada to Cheaha Mountain in the U.S...

. The other theory is that they have been there for thousands of years.

Some historians believe that Cherokees came to Appalachia as late as the 13th century. Over time they moved into Muscogee Creek territory and settled on the sites of Muscogee mounds. Several Mississippian sites have been misattributed to the Cherokee, including Moundville

Moundville Archaeological Site

Moundville Archaeological Site, also known as the Moundville Archaeological Park, is a Mississippian site on the Black Warrior River in Hale County, near the town of Tuscaloosa, Alabama...

and Etowah Mounds

Etowah Indian Mounds

Etowah Indian Mounds is a archaeological site in Bartow County, Georgia south of Cartersville, in the United States. Built and occupied in three phases, from 1000–1550 CE, the prehistoric site is located on the north shore of the Etowah River. Etowah Indian Mounds Historic Site is a designated...

but are in fact Muscogee Creek. Pisgah Phase

Pisgah Phase

The Pisgah Phase is an archaeological phase of the South Appalachian Mississippian culture in parts of Northeastern Tennessee, Western North Carolina and Northwestern South Carolina.-Location:...

sites are associated with precontact Cherokee culture, and historic Cherokee villages featured artifacts with iconography from the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex

Southeastern Ceremonial Complex

The Southeastern Ceremonial Complex is the name given to the regional stylistic similarity of artifacts, iconography, ceremonies, and mythology of the Mississippian culture that coincided with their adoption of maize agriculture and chiefdom-level complex social organization from...

.

The other possibility is that Cherokee people have lived in western North Carolina and eastern Tennessee for a far longer period of time. During the late Archaic and Woodland Period, Indians in the region began to cultivate plants such as marsh elder, lambsquarters, pigweed

Pigweed

Pigweed can mean any of a number of weedy plants which may be used as pig fodder:* Amaranthus species** Amaranthus palmeri, the 'pigweed' resistant to glyphosate in the US southeast.* Chenopodium album * Portulaca species...

, sunflowers and some native squash. People began building mounds, created new art forms such as shell gorget

Shell gorget

A shell gorget is a Native American art form of polished, carved shell pendants worn around the neck. The gorgets are frequently engraved, and are sometimes highlighted with pigments, or fenestrated ....

s, adopted new technologies, and followed an elaborate cycle of religious ceremonies. During Mississippian Period (800 to 1500 CE), Cherokee ancestors developed a new variety of corn called eastern flint, which closely resembles modern corn. Corn was central to several religious ceremonies, especially the Green Corn Ceremony

Green Corn Ceremony

The Green Corn Ceremony is an English term that refers to a general religious and social theme celebrated by a number of American Indian peoples of the Eastern Woodlands and the Southeastern tribes...

.

Early culture

John Howard Payne

John Howard Payne was an American actor, poet, playwright, and author who had most of his theatrical career and success in London. He is today most remembered as the creator of "Home! Sweet Home!", a song he wrote in 1822 that became widely popular in the United States, Great Britain, and the...

. The Payne papers describe the account by Cherokee elders of a traditional societal structure in which a "white" organization of elders represented the seven clans. According to Payne, this group, which was hereditary and described as priestly, was responsible for religious activities such as healing, purification, and prayer. A second group of younger men, the "red" organization, was responsible for warfare. Warfare was considered a polluting activity, which required the purification of the priestly class before participants could reintegrate into normal village life. This hierarchy had disappeared long before the 18th century. The reasons for the change have been debated, with the origin of the decline often located with a revolt by the Cherokee against the abuses of the priestly class known as the Ani-kutani

Ani-kutani

The Ani-kutani were the ancient priesthood of the Cherokee people. According to Cherokee legend, the Ani-Kutani were slain during a mass uprising by the Cherokee people approximately 300 years prior to European contact. This uprising was sparked by the fact that the Ani-Kutani had become corrupt...

.

Ethnographer James Mooney

James Mooney

James Mooney was an American ethnographer who lived for several years among the Cherokee. He did major studies of Southeastern Indians, as well as those on the Great Plains...

, who studied the Cherokee in the late 1880s, first traced the decline of the former hierarchy to this revolt. By the time of Mooney, the structure of Cherokee religious practitioners was more informal, based more on individual knowledge and ability than upon heredity.

Another major source of early cultural history comes from materials written in the 19th century by the didanvwisgi (Cherokee:ᏗᏓᏅᏫᏍᎩ), Cherokee medicine men

Medicine man

"Medicine man" or "Medicine woman" are English terms used to describe traditional healers and spiritual leaders among Native American and other indigenous or aboriginal peoples...

, after Sequoyah

Sequoyah

Sequoyah , named in English George Gist or George Guess, was a Cherokee silversmith. In 1821 he completed his independent creation of a Cherokee syllabary, making reading and writing in Cherokee possible...

's creation of the Cherokee syllabary

Cherokee syllabary

The Cherokee syllabary is a syllabary invented by Sequoyah to write the Cherokee language in the late 1810s and early 1820s. His creation of the syllabary is particularly noteworthy in that he could not previously read any script. He first experimented with logograms, but his system later developed...

in the 1820s. Initially only the didanvwisgi used these materials, which were considered extremely powerful. Later, the writings were widely adopted by the Cherokee people.

Unlike most other Indians in the American southeast at the start of the historic era, the Cherokee spoke an Iroquoian language

Iroquoian languages

The Iroquoian languages are a First Nation and Native American language family.-Family division:*Ruttenber, Edward Manning. 1992 [1872]. History of the Indian tribes of Hudson's River. Hope Farm Press....

. Since the Great Lakes

Great Lakes

The Great Lakes are a collection of freshwater lakes located in northeastern North America, on the Canada – United States border. Consisting of Lakes Superior, Michigan, Huron, Erie, and Ontario, they form the largest group of freshwater lakes on Earth by total surface, coming in second by volume...

region was the core of Iroquoian language speakers, scholars have theorized that the Cherokee migrated south from that region. However, some argue that the Iroquois migrated north from the southeast, with the Tuscarora breaking off from that group during the migration. Linguistic analysis shows a relatively large difference between Cherokee and the northern Iroquoian languages, suggesting a split in the distant past. Glottochronology

Glottochronology

Glottochronology is that part of lexicostatistics dealing with the chronological relationship between languages....

studies suggest the split occurred between about 1,500 and 1,800 B.C. The ancient settlement of Kituwa on the Tuckasegee River, formerly next to and now part of Qualla Boundary

Qualla Boundary

The Qualla Boundary is the territory where the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians reside in western North Carolina.-Location:...

(the reservation of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians

Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians

The Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians , is a federally recognized Native American tribe in the United States of America, who are descended from Cherokee who remained in the Eastern United States while others moved, or were forced to relocate, to the west in the 19th century. The history of the...

), is often cited as the original Cherokee settlement in the Southeast.

16th century: Spanish contact

In 1827 Cherokee Principal Chief Charles R. Hicks wrote eight letters to the newly elected Principal Chief, John Ross, describing the Cherokee's history in detail. In these letters he stated that the Cherokees had arrived in the thinly populated Southern Highlands shortly before the arrival of the English. The Cherokees had killed or driven off the Muskogean peoples who built mounds; burned their temples and erected round Cherokee council houses in the place of the temples. Hicks stated that the first Cherokee town in the Smoky Mountains region was Big Tellico. Hicks also specifically stated that the Cherokees never built any mounds, but did place town houses (council houses) on mounds built by others.In 1976 Caucasian archaeologist, Roy Dickens, published "Cherokee Archaeology," which presented a starkly different version of Cherokee history. It claimed that the Cherokees had lived in North Carolina for at least 1000 years and built the mounds in the region. In the decades since the book's publishing, Dickens' theories have be interpolated with assumptions made by others about the Spanish exploration of the Southern Highlands to create an early history of the tribe that is entirely different than that described by Principal Chief Hicks.

In fact, there are no Cherokee words mentioned in the chronicles of either the de Soto or Pardo Expedition. All place names and political titles mentioned by de Soto's chroniclers, while the expedition was traveling through Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina and eastern Tennessee are contemporary Creek Indian words. Approximately, 75% of Native American place names in the North Carolina Mountains are of Muskogean origin and have no meaning in Cherokee other than being proper nouns. For example, the name of the Oconaluftee River flowing through the reservation of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians comes from the Creek words, Okonee-luftee, which mean "Oconee (branch of Creeks) separated."

Lawson's version of Cherokee history has been formerly adopted by the Eastern Band of Cherokees. It is as follows:

The first known European-Cherokee and African-Cherokee contact was in 1540, when a Spanish expedition led by Hernando de Soto passed through Cherokee country. De Soto's expedition visited many of the Georgia and Tennessee villages later identified as Cherokee, but recorded them as then ruled by the Coosa chiefdom

Coosa chiefdom

The Coosa chiefdom was a powerful Native American paramount chiefdom near what are now Gordon and Murray counties in Georgia, in the United States. It was inhabited from about 1400 until about 1600, and dominated several smaller chiefdoms...

, while a Chalaque nation was recorded as living around the Keowee River

Keowee River

The Keowee River is created by the confluence of the Toxaway River and the Whitewater River in northern Oconee County, South Carolina. The confluence is today submerged beneath the waters of Lake Jocassee, a reservoir created by Lake Jocassee Dam....

where North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia meet.<ref>Mooney Diseases brought by the Spaniards and their animals decimated the Cherokee and other Eastern tribes.

A second Spanish expedition came through Cherokee country in 1567 led by Juan Pardo

Juan Pardo (explorer)

Juan Pardo was a Spanish explorer and conquistador who was active in the later half of the sixteenth century. He led a Spanish expedition through what is now North and South Carolina and into eastern Tennessee. He established Fort San Felipe, South Carolina , and the village of Santa Elena on...

. Spanish troops built six forts in the interior southeast. They visited the Cherokee towns Nikwasi

Nikwasi

Nikwasi was an important Cherokee town located on the Little Tennessee River at the site of present-day Franklin, North Carolina....

, Estatoe, Tugaloo, Conasauga, and Kituwa, but ultimately failed to gain dominion over the region and retreated to the coast.

It should be noted that neither Nikwasi, Estatoe, Tugaloo or Kituwa are mentioned in Juan Pardo's chronicles. The town of Conasaugua was mentioned, but is the Castilian spelling for a Muskogean word meaning, Hognose Skunk Clan. The descendants of this clan maintain a dance ground in the Creek section of Oklahoma to this day.

17th century: English contact

In 1673, two Englishmen, James Needham and Garbiel Arthur were sent to Overhill Cherokee county in 1673 by fur-trader Abraham Wood

Abraham Wood

Abraham Wood , sometimes referred to as "General" or "Colonel" Wood, was an English fur trader and explorer of 17th century colonial Virginia...

from Fort Henry (modern Petersburg, Virginia

Petersburg, Virginia

Petersburg is an independent city in Virginia, United States located on the Appomattox River and south of the state capital city of Richmond. The city's population was 32,420 as of 2010, predominantly of African-American ethnicity...

). Wood hoped to forge a direct trading connection with the Cherokee to bypass the Occaneechi

Occaneechi

The Occaneechi are Native Americans who lived primarily on a large, long Occoneechee Island and east of the confluence of the Dan and Roanoke Rivers, near current day Clarksville, Virginia in the 17th century...

Indians, who were serving as middlemen on the Trading Path

Trading Path

The Trading Path is not simply one wide path, as many named historic roads were or are...

. The two colonial Virginians probably did make contact with the Cherokees. However, Wood called them Rickohockens in his book on the expedition. The map accompanying the book, showed the Rickohockens occupying all of present day southwestern Virginia, southeastern Kentucky, nortwestern North Carolina and the northeastern tip of Tennessee.

Needham departed with a guide nicknamed 'Indian John' while Arthur was left behind to learn the Cherokee language. On his journey, Needham engaged in an argument with 'Indian John', resulting in his death. 'Indian John' then tried to encourage his tribe to kill Arthur but the chief prevented this. Arthur, disguised as a Cherokee, accompanied the chief of the Cherokee tribe at Chota on raids of Spanish settlements in Florida, Indian communities on the east coast, and Shawnee towns on the Ohio River. However, in 1674 he was captured by the Shawnee Indians who discovered that under his disguise of clay and ash he was a white man. The Shawnee did not kill Arthur but alternatively allowed him to return to Chota. In June of 1674, the chief escorted Arthur back to his English settlement in Virginia. By the late 17th century, colonial traders from both Virginia and South Carolina were making regular journeys to Cherokee lands, but few wrote about their experiences.

The character and events of the early trading contact period have been pieced together by historians' examination of records of colonial laws and lawsuits involving traders. The trade was mainly deerskins

Deerskin trade

The deerskin trade between Colonial America and the Native Americans was one of the most important trading relationships between Europeans and Native Americans, especially in the southeast. It was a form of the fur trade, but less known, since deer skins were not as valuable as furs from the north...

, raw material for the booming European leather industry, in exchange for European technology "trade goods", such as iron and steel tools (kettles, knives, etc.), firearms, gunpowder, and ammunition. In 1705, traders complained that their business had been lost and replaced by Indian slave trade instigated by Governor James Moore

James Moore (South Carolina politician)

James Moore was the British governor of colonial South Carolina between 1700 and 1703. He is remembered for leading several invasions of Spanish Florida, including attacks in 1704 and 1706 which wiped out most of the Spanish missions in Florida....

of South Carolina. Moore had commissioned people to "set upon, assault, kill, destroy, and take captive as many Indians as possible". When the captives were sold, traders split profits with the Governor. Although colonial governments early prohibited selling alcohol to Indians, traders commonly used rum, and later whiskey, as common items of trade.

During the early historic era, Europeans wrote of several Cherokee town groups, usually using the terms Lower, Middle, and Overhill

Overhill Cherokee

The term Overhill Cherokee refers to the former Cherokee settlements located in what is now Tennessee in the southeastern United States. The name was given by 18th century European traders and explorers who had to cross the Appalachian Mountains to reach these settlements when traveling from...

towns to designate the towns, from the Piedmont across the Allegheny Mountains. The Lower Towns were situated on the headwater streams of the Savannah River

Savannah River

The Savannah River is a major river in the southeastern United States, forming most of the border between the states of South Carolina and Georgia. Two tributaries of the Savannah, the Tugaloo River and the Chattooga River, form the northernmost part of the border...

, mainly in present-day western South Carolina

South Carolina

South Carolina is a state in the Deep South of the United States that borders Georgia to the south, North Carolina to the north, and the Atlantic Ocean to the east. Originally part of the Province of Carolina, the Province of South Carolina was one of the 13 colonies that declared independence...

and northeastern Georgia

Georgia (U.S. state)

Georgia is a state located in the southeastern United States. It was established in 1732, the last of the original Thirteen Colonies. The state is named after King George II of Great Britain. Georgia was the fourth state to ratify the United States Constitution, on January 2, 1788...

. Keowee

Keowee

Keowee was a Cherokee town in the north of present-day South Carolina. It was settled in what is present day Oconee County, the westernmost county of South Carolina, at the foot of the Blue Ridge Mountains, just north of Clemson...

was one of the chief towns, as was Tugaloo.

The Middle Towns were located in present western North Carolina

North Carolina

North Carolina is a state located in the southeastern United States. The state borders South Carolina and Georgia to the south, Tennessee to the west and Virginia to the north. North Carolina contains 100 counties. Its capital is Raleigh, and its largest city is Charlotte...

, on the headwater streams of the Tennessee River

Tennessee River

The Tennessee River is the largest tributary of the Ohio River. It is approximately 652 miles long and is located in the southeastern United States in the Tennessee Valley. The river was once popularly known as the Cherokee River, among other names...

, such as the upper Little Tennessee River

Little Tennessee River

The Little Tennessee River is a tributary of the Tennessee River, approximately 135 miles long, in the Appalachian Mountains in the southeastern United States.-Geography:...

, upper Hiwassee River

Hiwassee River

The Hiwassee River has its headwaters on the north slope of Rocky Mountain in Towns County in northern Georgia and flows northward into North Carolina before turning westward into Tennessee, flowing into the Tennessee River a few miles west of State Route 58 in Meigs County, Tennessee...

, and upper French Broad River

French Broad River

The French Broad River flows from near the village of Rosman in Transylvania County, North Carolina, into the state of Tennessee. Its confluence with the Holston River at Knoxville is the beginning of the Tennessee River....

. Among several chief towns were Nikwasi

Nikwasi

Nikwasi was an important Cherokee town located on the Little Tennessee River at the site of present-day Franklin, North Carolina....

and Joara

Joara

Joara was a large Native American settlement, a regional chiefdom of the Mississippian culture, located in what is now Burke County, North Carolina. Joara is notable as a significant archaeological and historic site. It was a place of encounter in 1540 between the Mississippian people and the...

, first recorded in the late 16th century during Spanish settlement there with the establishment of Fort San Juan.

The Overhill Towns were located across the higher mountains in present eastern Tennessee

Tennessee

Tennessee is a U.S. state located in the Southeastern United States. It has a population of 6,346,105, making it the nation's 17th-largest state by population, and covers , making it the 36th-largest by total land area...

and northwestern Georgia. Principal towns included Chota

Chota (Cherokee town)

Chota is a historic Overhill Cherokee site in Monroe County, Tennessee, in the southeastern United States. For much of its history, Chota was the most important of the Overhill towns, serving as the de facto capital of the Cherokee people from the late 1740s until 1788...

, Tellico

Great Tellico

Great Tellico was a Cherokee town at the site of present-day Tellico Plains, Tennessee, where the Tellico River emerges from the Appalachian Mountains. Great Tellico was one of the largest Cherokee towns in the region, and had a sister town nearby named Chatuga. Its name in Cherokee is more...

, and Tanasi

Tanasi

Tanasi is a historic Overhill Cherokee village site in Monroe County, Tennessee, in the southeastern United States. The village is best known as the namesake for the state of Tennessee...

. These terms were created and used by Europeans to describe their changing geopolitical relationship with the Cherokee.

There were two more groups of towns often listed as part of the three: the Out Towns, whose chief town was Kituwa on the Tuckaseegee River, considered the mother town of all Cherokee; and the Valley Towns, whose chief town was Tomotley on the Valley River (not the same as the Tomotley

Tomotley

Tomotley is a prehistoric and historic Native American site in Monroe County, Tennessee, in the southeastern United States. Occupied as early as the Archaic period, the Tomotley site had the most substantial periods of habitation during the Mississippian period, likely when the earthwork mounds...

on the Little Tennessee River

Little Tennessee River

The Little Tennessee River is a tributary of the Tennessee River, approximately 135 miles long, in the Appalachian Mountains in the southeastern United States.-Geography:...

). The former shared the dialect of the Middle Towns and the latter that of the Overhill (later Upper) Towns.

Of the southeastern Indian confederacies of the late 17th and early 18th centuries (Creek, Chickasaw, Choctaw, etc.), the Cherokee were one of the most populous and powerful. They were relatively isolated by their hilly and mountainous homeland. A small-scale trading system was established with Virginia in the late 17th century. In the 1690s, the Cherokee had founded a much stronger and important trade relationship with the colony of South Carolina, based in Charles Town

Charleston, South Carolina

Charleston is the second largest city in the U.S. state of South Carolina. It was made the county seat of Charleston County in 1901 when Charleston County was founded. The city's original name was Charles Towne in 1670, and it moved to its present location from a location on the west bank of the...

. By the 18th century, this overshadowed the Virginia relationship.

18th century history

Yamasee

The Yamasee were a multiethnic confederation of Native Americans that lived in the coastal region of present-day northern coastal Georgia near the Savannah River and later in northeastern Florida.-History:...

, Catawba

Catawba (tribe)

The Catawba are a federally recognized tribe of Native Americans, known as the Catawba Indian Nation. They live in the Southeast United States, along the border between North and South Carolina near the city of Rock Hill...

, and British in late 1712 and early 1713, against the Tuscarora in the Second Tuscarora War

Tuscarora War

The Tuscarora War was fought in North Carolina during the autumn of 1711 until 11 February 1715 between the British, Dutch, and German settlers and the Tuscarora Native Americans. A treaty was signed in 1715....

. The Tuscarora War marked the beginning of an English-Cherokee relationship that, despite breaking down on occasion, remained strong for much of the 18th century.

In January 1716, a delegation of Muscogee Creek leaders was murdered at the Cherokee town of Tugaloo

Tugaloo (Cherokee town)

Tugaloo was a Cherokee town on the Tugaloo River, at the mouth of Toccoa Creek, near present-day Toccoa, Georgia and very near the historic tavern called Travelers Rest....

, marking the Cherokee's entry into the Yamasee War

Yamasee War

The Yamasee War was a conflict between British settlers of colonial South Carolina and various Native American Indian tribes, including the Yamasee, Muscogee, Cherokee, Chickasaw, Catawba, Apalachee, Apalachicola, Yuchi, Savannah River Shawnee, Congaree, Waxhaw, Pee Dee, Cape Fear, Cheraw, and...

, which ended in 1717 with peace treaties between South Carolina

South Carolina

South Carolina is a state in the Deep South of the United States that borders Georgia to the south, North Carolina to the north, and the Atlantic Ocean to the east. Originally part of the Province of Carolina, the Province of South Carolina was one of the 13 colonies that declared independence...

and the Creeks. Hostility and sporadic raids between the Cherokee and Creek continued for decades. These raids came to a head at the Battle of Taliwa

Battle of Taliwa

The Battle of Taliwa was fought in Ball Ground, Georgia in 1755. According to Cherokee folklore, it was mainly fought over land disputed between the Cherokees and Creek, with the Cherokees winning...

in 1755 (in present-day Ball Ground, Georgia

Ball Ground, Georgia

Ball Ground is a city in Cherokee County, Georgia, United States. The population was 1433 at the 2010 census.Ball Ground is at the northernmost end of Georgia Interstate 575, north of Canton at exit 20 on I-575, and ending seven miles north at exit 27...

) resulting in the defeat of the Muscogee.

In 1721, the Cherokee ceded lands to South Carolina

South Carolina

South Carolina is a state in the Deep South of the United States that borders Georgia to the south, North Carolina to the north, and the Atlantic Ocean to the east. Originally part of the Province of Carolina, the Province of South Carolina was one of the 13 colonies that declared independence...

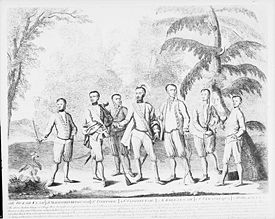

. In 1730, at Nikwasi

Nikwasi

Nikwasi was an important Cherokee town located on the Little Tennessee River at the site of present-day Franklin, North Carolina....

, a manipulative Britain, Sir Alexander Cumming, convinced Cherokees to crown Moytoy of Tellico as "Emperor." Moytoy agreed to recognize King George II of Great Britain

George II of Great Britain

George II was King of Great Britain and Ireland, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg and Archtreasurer and Prince-elector of the Holy Roman Empire from 11 June 1727 until his death.George was the last British monarch born outside Great Britain. He was born and brought up in Northern Germany...

as the Cherokee protector. Seven prominent Cherokee, including Attakullakulla, traveled with Cuming back to London, England. The Cherokee delegation signed the Treaty of Whitehall

Treaty of Whitehall

The Treaty of Whitehall was signed between Louis XIV of France and James II of England in November 1686 as an agreement that Continental conflict would not disrupt peace and neutrality in New France and New England...

with the British. Moytoy's son, Amo-sgasite (Dreadful Water) attempted to succeed him as "Emperor" in 1741, but the Cherokees elected their own leader, Standing Turkey

Standing Turkey

Standing Turkey — also known as Cunne Shote or Kunagadoga — succeeded his uncle, Kanagatucko, or Old Hop, as First Beloved Man of the Cherokee upon the latter's death in 1760...

of Chota

Chota (Cherokee town)

Chota is a historic Overhill Cherokee site in Monroe County, Tennessee, in the southeastern United States. For much of its history, Chota was the most important of the Overhill towns, serving as the de facto capital of the Cherokee people from the late 1740s until 1788...

(or, sometimes, Echota).

Political power among Cherokees remained decentralized with towns acting autonomously. In 1735 the Cherokee were estimated to have sixty-four towns and villages and 6000 fighting men. In 1738 and 1739 smallpox

Smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease unique to humans, caused by either of two virus variants, Variola major and Variola minor. The disease is also known by the Latin names Variola or Variola vera, which is a derivative of the Latin varius, meaning "spotted", or varus, meaning "pimple"...

epidemics broke out among the Cherokee, who had no natural immunity. Nearly half their population died within a year. Many —possibly hundreds —of the Cherokee people also committed suicide due to disfigurement from the disease.

From 1753 to 1755, battles broke out between the Cherokee and Muscogee over disputed hunting grounds in North Georgia

North Georgia

North Georgia is the hilly to mountainous northern region of the U.S. state of Georgia. At the time of the arrival of settlers from Europe, it was inhabited largely by the Cherokee. The counties of North Georgia were often scenes of important events in the history of Georgia...

. Cherokees were victorious in the Battle of Taliwa. British soldiers built forts in Cherokee country to confront the French, including Fort Loudoun

Fort Loudoun

Fort Loudoun was the name of three British forts built during the French and Indian War in North America. They were named for John Campbell, 4th Earl of Loudoun.*Fort Loudoun in present-day Monroe County, Tennessee...

, near Chota. In 1756 the Cherokees fought along side the British in the French and Indian War

French and Indian War

The French and Indian War is the common American name for the war between Great Britain and France in North America from 1754 to 1763. In 1756, the war erupted into the world-wide conflict known as the Seven Years' War and thus came to be regarded as the North American theater of that war...

; however, serious misunderstandings between the two allies arose quickly, resulting in the 1760 Anglo-Cherokee War

Anglo-Cherokee War

The Anglo-Cherokee War , also known as the Cherokee War, the Cherokee Uprising, the Cherokee Rebellion, was a conflict between British forces in North America and Cherokee Indians during the French and Indian War...

. The Royal Proclamation of 1763

Royal Proclamation of 1763

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 was issued October 7, 1763, by King George III following Great Britain's acquisition of French territory in North America after the end of the French and Indian War/Seven Years' War...

issued by King George III forbade British settlements west of the Appalachian crest, attempting to afford some temporary protection from colonial encroachment

Encroachment

Encroachment is a term which implies "advance beyond proper limits," and may have different interpretations depending on the context. Encroachment may refer to one of the following:* Temporal encroachment* Structural encroachment...

to the Cherokee, but it proved difficult to enforce.

In 1769–72, predominantly Virginian settlers squatting on Cherokee lands in Tennessee, formed the Watauga Association

Watauga Association

The Watauga Association was a semi-autonomous government created in 1772 by frontier settlers living along the Watauga River in what is now present day Elizabethton, Tennessee...

. In "Kentuckee"

Kentucky

The Commonwealth of Kentucky is a state located in the East Central United States of America. As classified by the United States Census Bureau, Kentucky is a Southern state, more specifically in the East South Central region. Kentucky is one of four U.S. states constituted as a commonwealth...

, Daniel Boone

Daniel Boone

Daniel Boone was an American pioneer, explorer, and frontiersman whose frontier exploits mad']'e him one of the first folk heroes of the United States. Boone is most famous for his exploration and settlement of what is now the Commonwealth of Kentucky, which was then beyond the western borders of...

and his party tried to create a settlement in what would become the Transylvania colony, but the Shawnee, Delaware

Lenape

The Lenape are an Algonquian group of Native Americans of the Northeastern Woodlands. They are also called Delaware Indians. As a result of the American Revolutionary War and later Indian removals from the eastern United States, today the main groups live in Canada, where they are enrolled in the...

, Mingo

Mingo

The Mingo are an Iroquoian group of Native Americans made up of peoples who migrated west to the Ohio Country in the mid-eighteenth century. Anglo-Americans called these migrants mingos, a corruption of mingwe, an Eastern Algonquian name for Iroquoian-language groups in general. Mingos have also...

, and some disgruntled Cherokee attacked a scouting and foraging party that included Boone’s son. This sparked the beginning of what was known as Dunmore's War

Dunmore's War

Dunmore's War was a war in 1774 between the Colony of Virginia and the Shawnee and Mingo American Indian nations....

(1773–1774).

In 1776, allied with the Shawnee and led by Cornstalk

Cornstalk

Cornstalk was a prominent leader of the Shawnee nation just prior to the American Revolution. His name, Hokoleskwa, translates loosely into "stalk of corn" in English, and is spelled Colesqua in some accounts...

, Cherokees attacked settlers in South Carolina, Georgia, Virginia, the Washington District

Washington District, North Carolina

The Washington District of North Carolina was in a remote area west of the Appalachian Mountains, officially existing for only a short period of time , although it had been self-proclaimed and functioning as an independent governing entity since the spring of 1775...

and North Carolina in the Second Cherokee War. An Overhill Cherokee, Nancy Ward

Nancy Ward

Nanyehi , known in English as Nancy Ward was a Ghigau, or Beloved Woman of the Cherokee Nation, which meant that she was allowed to sit in councils and to make decisions, along with the other Beloved Women, on pardons...

(a niece of Dragging Canoe

Dragging Canoe

Tsiyu Gansini , "He is dragging his canoe", known to whites as Dragging Canoe, was a Cherokee war chief who led a band of Cherokee against colonists and United States settlers...

), warned settlers of the impending aggression. European-American militias retaliated, destroying over 50 Cherokee towns. In 1777, most of the surviving Cherokee town leaders signed treaties with the states.

Dragging Canoe and his band, however, moved to the area near present day Chattanooga, Tennessee

Chattanooga, Tennessee

Chattanooga is the fourth-largest city in the US state of Tennessee , with a population of 169,887. It is the seat of Hamilton County...

, establishing 11 new towns. Chickamauga was his headquarters and his entire band was known as the Chickamaugas. From here he fought a guerrilla-style war, the Chickamauga Wars (1776-1794). The Treaty of Tellico Blockhouse, signed 7 November 1794, ended the Chickamauga wars.

19th century

Little Turkey

Little Turkey was elected First Beloved Man by the general council of the Cherokee upon the move of the council's seat to Ustanali on the Conasauga River following the murder of Corntassel in 1788...

(1788–1801), Black Fox (1801–1811), and Pathkiller

Pathkiller

Pathkiller, , fought in the Revolutionary War for Britain, then in the Chickamauga Wars against American frontiersmen . He was the Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation from 1811-1827. Pathkiller, a fullblood, "unacculturated" Cherokee, was the last individual from a conservative background to...

(1811–1827).

The seat of the Upper Towns was at Ustanali (near Calhoun, Georgia

Calhoun, Georgia

Calhoun is a city in Gordon County, Georgia, United States. As of the 2010 census, the city had a population of 15,650. The city is the county seat of Gordon County.-Geography:Calhoun is located at , along the Oostanaula River....

), also the titular seat of the Nation, and with the former warriors James Vann and his protégés The Ridge

Major Ridge

Major Ridge, The Ridge was a Cherokee Indian member of the tribal council, a lawmaker, and a leader. He was a veteran of the Chickamauga Wars, the Creek War, and the First Seminole War.Along with Charles R...

(formerly known as Pathkiller) and Charles R. Hicks

Charles R. Hicks

Charles Renatus Hicks was one of the most important Cherokee leaders in the early 19th century; together with James Vann and Major Ridge, he was one of a triumvirate of younger chiefs urging the tribe to acculturate to European-American ways and supported a Moravian mission school to educate the...

, the "Cherokee Triumvirate", as their dominant leaders, particularly of the younger more acculturated generation. The leaders of these towns were the most progressive, favoring acculturation, formal education, and modern methods of farming.

Facing removal, the Lower Cherokee were the first to move west. Remaining Lower Town leaders, such as Young Dragging Canoe and Sequoyah

Sequoyah

Sequoyah , named in English George Gist or George Guess, was a Cherokee silversmith. In 1821 he completed his independent creation of a Cherokee syllabary, making reading and writing in Cherokee possible...

, were strong advocates of voluntary relocation.

Removal era

In 1815, the US government established a Cherokee Reservation in Arkansas. The reservation boundaries extended from north of the Arkansas RiverArkansas River

The Arkansas River is a major tributary of the Mississippi River. The Arkansas generally flows to the east and southeast as it traverses the U.S. states of Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Arkansas. The river's initial basin starts in the Western United States in Colorado, specifically the Arkansas...

to the southern bank of the White River. The Bowl

The Bowl (Cherokee chief)

The Bowl was one of the leaders of the Chickamauga Cherokee under Dragging Canoe who fought against the United States of America during the Chickamauga wars...

, Sequoyah, Spring Frog and Tatsi (Dutch) and their bands settled there. These Cherokees became known as "Old Settlers."

John Ross

John Ross (Cherokee chief)

John Ross , also known as Guwisguwi , was Principal Chief of the Cherokee Native American Nation from 1828–1866...

became the Principal Chief of the tribe in 1828 and remained the chief until his death in 1866.

Treaty party

Among the Cherokee, John Ross led the battle to halt their removal. Ross' supporters, commonly referred to as the "National Party," were opposed by a group known as the "Ridge Party" or the "Treaty Party". The Treaty Party signed the Treaty of New EchotaTreaty of New Echota

The Treaty of New Echota was a treaty signed on December 29, 1835, in New Echota, Georgia by officials of the United States government and representatives of a minority Cherokee political faction, known as the Treaty Party...

, stipulating terms and conditions for the removal of the Cherokee Nation from the lands in the East for lands in Indian Territory

Indian Territory

The Indian Territory, also known as the Indian Territories and the Indian Country, was land set aside within the United States for the settlement of American Indians...

.

Trail of Tears

Gold rush

A gold rush is a period of feverish migration of workers to an area that has had a dramatic discovery of gold. Major gold rushes took place in the 19th century in Australia, Brazil, Canada, South Africa, and the United States, while smaller gold rushes took place elsewhere.In the 19th and early...

around Dahlonega, Georgia

Dahlonega, Georgia

Dahlonega is a city in Lumpkin County, Georgia, United States, and is its county seat. As of the 2010 census, the city had a population of 5,242....

in the 1830s. President Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson was the seventh President of the United States . Based in frontier Tennessee, Jackson was a politician and army general who defeated the Creek Indians at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend , and the British at the Battle of New Orleans...

said removal policy was an effort to prevent the Cherokee from facing the fate of "the Mohegan

Mohegan

The Mohegan tribe is an Algonquian-speaking tribe that lives in the eastern upper Thames River valley of Connecticut. Mohegan translates to "People of the Wolf". At the time of European contact, the Mohegan and Pequot were one people, historically living in the lower Connecticut region...

, the Narragansett, and the Delaware". However there is ample evidence that the Cherokee were adapting modern farming techniques, and a modern analysis shows that the area was in general in a state of economic surplus.

In June 1830, a delegation of Cherokees led by Chief Ross brought their grievances about tribal sovereignty over state government to the US Supreme Court in the Cherokee Nation v. Georgia

Cherokee Nation v. Georgia

Cherokee Nation v. Georgia, , was a United States Supreme Court case. The Cherokee Nation sought a federal injunction against laws passed by the state of Georgia depriving them of rights within its boundaries, but the Supreme Court did not hear the case on its merits...

case. In the case Worcester v. Georgia

Worcester v. Georgia

Worcester v. Georgia, 31 U.S. 515 , was a case in which the United States Supreme Court vacated the conviction of Samuel Worcester and held that the Georgia criminal statute that prohibited non-Indians from being present on Indian lands without a license from the state was unconstitutional.The...

, the United States Supreme Court

Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States is the highest court in the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all state and federal courts, and original jurisdiction over a small range of cases...

held that Cherokee Native Americans were entitled to federal protection from the actions of state governments. Worcester v. Georgia is considered one of the most important decisions in law dealing with Native Americans.

Despite the Worcester v. Georgia

Worcester v. Georgia

Worcester v. Georgia, 31 U.S. 515 , was a case in which the United States Supreme Court vacated the conviction of Samuel Worcester and held that the Georgia criminal statute that prohibited non-Indians from being present on Indian lands without a license from the state was unconstitutional.The...

ruling in their favor, the majority of Cherokees were forcibly relocated westward to Indian Territory

Indian Territory

The Indian Territory, also known as the Indian Territories and the Indian Country, was land set aside within the United States for the settlement of American Indians...

in 1838–1839, a migration known as the Trail of Tears

Trail of Tears

The Trail of Tears is a name given to the forced relocation and movement of Native American nations from southeastern parts of the United States following the Indian Removal Act of 1830...

or in Cherokee ᏅᎾ ᏓᎤᎳ ᏨᏱ or Nvna Daula Tsvyi (Cherokee: The Trail Where They Cried). This took place during the Indian Removal Act

Indian Removal Act

The Indian Removal Act was signed into law by President Andrew Jackson on May 28, 1830.The Removal Act was strongly supported in the South, where states were eager to gain access to lands inhabited by the Five Civilized Tribes. In particular, Georgia, the largest state at that time, was involved in...

of 1830. The harsh treatment the Cherokee received at the hands of white settlers caused some to enroll to emigrate west. As some Cherokees were slaveholders, they took enslaved African-Americans with them west of the Mississippi. Intermarried European-Americans and missionaries also walked the Trail of Tears.

On June 22, 1839, Major Ridge, John Ridge and Elias Boudinot

Elias Boudinot (Cherokee)

Elias Boudinot , was a member of an important Cherokee family in present-day Georgia. They believed that rapid acculturation was critical to Cherokee survival. In 1828 Boudinot became the editor of the Cherokee Phoenix, which was published in Cherokee and English...

were assassinated by a party of twenty-five extremist Ross supporters that included Daniel Colston, John Vann, Archibald Spear, James Spear, Joseph Spear, Hunter, and others. Stand Watie

Stand Watie

Stand Watie , also known as Standhope Uwatie, Degataga , meaning “stand firm”), and Isaac S. Watie, was a leader of the Cherokee Nation and a brigadier general of the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War...

fought off the attempt on his life that day and escaped to Arkansas

Arkansas

Arkansas is a state located in the southern region of the United States. Its name is an Algonquian name of the Quapaw Indians. Arkansas shares borders with six states , and its eastern border is largely defined by the Mississippi River...

.

Eastern Band

William Holland Thomas

William Holland Thomas was Principal Chief of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians and an officer in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War....

, a white storeowner and state legislator from Jackson County, North Carolina

Jackson County, North Carolina

Jackson County is a county located in the southwest of the U.S. state of North Carolina. As of 2010, the population was 40,271. Since 1913 its county seat has been Sylva, replacing Webster.-History:...

, helped over 600 Cherokee from Qualla Town

Cherokee, North Carolina

Cherokee is a town in Swain County, North Carolina, USA, within the Qualla Boundary land trust. It is located in the Oconaluftee River Valley, near the intersection of U.S. Route 19 and U.S...

obtain North Carolina citizenship, which exempted them from forced removal. Over 400 other Cherokee either hid from Federal troops in the remote Snowbird Mountains, under the leadership of Tsali

Tsali

Tsali, originally of Coosawattee Town , was a noted figure at two different periods of Cherokee history, both of them vital.From which of the main divisions of the Cherokee prior to the American Revolution he came is not known, but records do indicate that as a young man he followed Dragging Canoe...

(ᏣᎵ), or belonged to in the former Valley Towns area around the Cheoah River

Cheoah River

The Cheoah River is a tributary of the Little Tennessee River in North Carolina in the United States.It is located in Graham County in far western North Carolina, near Robbinsville, and is approximately 20 miles in length...

who negotiated to stay in North Carolina with the state government. An additional 400 Cherokee stayed on reserves in Southeast Tennessee, North Georgia, and Northeast Alabama, as citizens of their respective states, mostly mixed-bloods and Cherokee women married to white men. Together, these groups were the basis for what is now known as the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians

Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians

The Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians , is a federally recognized Native American tribe in the United States of America, who are descended from Cherokee who remained in the Eastern United States while others moved, or were forced to relocate, to the west in the 19th century. The history of the...

.

Civil War

The American Civil WarAmerican Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

was devastating for both East and Western Cherokees. Those Cherokees aided by William Thomas became the Thomas Legion of Cherokee Indians and Highlanders, fighting for the Confederacy in the American Civil War

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

. Cherokees in Indian Territory split into Confederate and Union factions.

Reconstruction and late 19th century

The US government also acquired easement rights to the western part of the territory, which became the Oklahoma Territory, for the construction of railroads. Development and settlers followed the railroads. By the late 19th century, the government believed that Native Americans would be better off if each family owned its own land. The Dawes Act

Dawes Act

The Dawes Act, adopted by Congress in 1887, authorized the President of the United States to survey Indian tribal land and divide the land into allotments for individual Indians. The Act was named for its sponsor, Senator Henry L. Dawes of Massachusetts. The Dawes Act was amended in 1891 and again...

of 1887 provided for the breakup of commonly held tribal land. Native Americans were registered on the Dawes Rolls and allotted land from the common reserve. This also opened up later sales of land by individuals to people outside the tribe.

Curtis Act of 1898

The Curtis Act of 1898 was an amendment to the United States Dawes Act that brought about the allotment process of lands of the Five Civilized Tribes of Indian Territory: the Choctaw, Chickasaw, Muscogee, Cherokee, and Seminole...

advanced the break-up of Native American government. For the Oklahoma Territory, this meant abolition of the Cherokee courts and governmental systems by the U.S. Federal Government. This was seen as necessary before the Oklahoma and Indian territories could be admitted as states.

By the late 19th century, the Eastern Band of Cherokees were laboring under the constraints of a segregated

Racial segregation

Racial segregation is the separation of humans into racial groups in daily life. It may apply to activities such as eating in a restaurant, drinking from a water fountain, using a public toilet, attending school, going to the movies, or in the rental or purchase of a home...

society. In the aftermath of Reconstruction, conservative white Democrats regained power in North Carolina and other southern states. They proceeded to effectively disfranchise all blacks and many poor whites by new constitutions and laws related to voter registration and elections. They passed Jim Crow laws

Jim Crow laws

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws in the United States enacted between 1876 and 1965. They mandated de jure racial segregation in all public facilities, with a supposedly "separate but equal" status for black Americans...

that divided society into "white" and "colored", mostly to control freedmen, but the Native Americans were included on the colored side and suffered the same racial segregation and disfranchisement as former slaves. Blacks and Native Americans would not regain their rights as US citizens until the Civil Rights Movement

Civil rights movement

The civil rights movement was a worldwide political movement for equality before the law occurring between approximately 1950 and 1980. In many situations it took the form of campaigns of civil resistance aimed at achieving change by nonviolent forms of resistance. In some situations it was...

and passage of civil rights legislation in the mid-1960s.

Notable Cherokees in history

- Attakullakulla (ca. 1708-ca. 1777), diplomat to Britain, headman of Chota and chief

- Bob BengeBob BengeBob Benge , also known as "Captain Benge" or "The Bench" to frontiersmen, was one of the most feared Cherokee leaders on the frontier during the Chickamauga wars.-Early life:...

(ca. 1762–1794), warrior of the ""Lower Cherokee"" during the Chickamauga wars - Elias BoudinotElias Boudinot (Cherokee)Elias Boudinot , was a member of an important Cherokee family in present-day Georgia. They believed that rapid acculturation was critical to Cherokee survival. In 1828 Boudinot became the editor of the Cherokee Phoenix, which was published in Cherokee and English...

, Galagina (1802–1839), statesman, orator, and editor, founded the first Cherokee newspaper, the Cherokee PhoenixCherokee PhoenixThe Cherokee Phoenix was the first newspaper published by Native Americans in the United States and the first published in a Native American language. The first issue was published in English and Cherokee on February 21, 1828, in New Echota, capital of the Cherokee Nation . The paper continued... - Ned ChristieNed ChristieNed Christie , also known as NeDe WaDe , was a Cherokee statesman. Ned was a member of the executive council in the Cherokee Nation senate, and served as one of three advisers to Chief Bushyhead...

(1852–1892), statesman, Cherokee NationCherokee Nation (19th century)The Cherokee Nation of the 19th century —an historic entity —was a legal, autonomous, tribal government in North America existing from 1794–1906. Often referred to simply as The Nation by its inhabitants, it should not be confused with what is known today as the "modern" Cherokee Nation...

senator, infamous outlawOutlawIn historical legal systems, an outlaw is declared as outside the protection of the law. In pre-modern societies, this takes the burden of active prosecution of a criminal from the authorities. Instead, the criminal is withdrawn all legal protection, so that anyone is legally empowered to persecute... - Rear Admiral Joseph J. ClarkJoseph J. ClarkAdmiral Joseph James "Jocko" Clark, USN was an admiral in the United States Navy, who commanded aircraft carriers during World War II. A native of Oklahoma, Clark was a member of the Cherokee tribe...

(1893–1971), United States Navy, highest ranking Native American in the US military - DoubleheadDoubleheadDoublehead or Incalatanga , was one of the most feared warriors of the Cherokee during the Chickamauga Wars. In 1788, his brother, Old Tassel, was chief of the Cherokee people, but was killed under a truce by frontier rangers. In 1791 Doublehead was among a delegation of Cherokees who visited U.S...

, Taltsuska (d. 1807), war leader during the Chickamauga wars, led the "Lower Cherokee", signed land deals with the U.S. - Dragging CanoeDragging CanoeTsiyu Gansini , "He is dragging his canoe", known to whites as Dragging Canoe, was a Cherokee war chief who led a band of Cherokee against colonists and United States settlers...

, Tsiyugunsini (1738–1792), general during the 2nd Cherokee War, principal chief of the Chickamauga (or "Lower Cherokee") - Franklin GrittsFranklin GrittsFranklin Gritts, also known as Oau Nah Jusah, or They Have Returned, was a Cherokee artist best known for his contributions to the "Golden Era" of Native American art, both as a teacher and an artist....

, Cherokee artist who taught at Haskell InstituteHaskell Indian Nations UniversityHaskell Indian Nations University is a tribal university located in Lawrence, Kansas, for members of federally recognized Native American tribes in the United States...

and served on the USS Franklin - Charles R. HicksCharles R. HicksCharles Renatus Hicks was one of the most important Cherokee leaders in the early 19th century; together with James Vann and Major Ridge, he was one of a triumvirate of younger chiefs urging the tribe to acculturate to European-American ways and supported a Moravian mission school to educate the...

(d. 1927), Second Principal Chief to PathkillerPathkillerPathkiller, , fought in the Revolutionary War for Britain, then in the Chickamauga Wars against American frontiersmen . He was the Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation from 1811-1827. Pathkiller, a fullblood, "unacculturated" Cherokee, was the last individual from a conservative background to...

in the early 17th century, de facto Principal Chief from 1813–1827 - JunaluskaJunaluskaJunaluska, or Tsunu’lahun’ski in Cherokee , was a leader of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians who reside in and around western North Carolina....

(ca. 1775–1868), veteran of the Creek War, who saved future president, Andrew Jackson's, life - OconostotaOconostotaOconostota was the Warrior of Chota and the First Beloved Man of the Cherokee from 1775 to 1781.-Meaning of the name:...

, Aganstata (ca. 1710–1783), "Beloved Man", war chief during the Anglo-Cherokee War - OstenacoOstenacoOstenaco , who preferred to go by the warrior's title he earned at any early age, "Mankiller" , also known as Judd's Friend, who lived c...

, Ustanakwa (ca. 1703–1780), war chief, diplomat to Britain, founded the town of Ultiwa - Major RidgeMajor RidgeMajor Ridge, The Ridge was a Cherokee Indian member of the tribal council, a lawmaker, and a leader. He was a veteran of the Chickamauga Wars, the Creek War, and the First Seminole War.Along with Charles R...

Ganundalegi or "Pathkiller" (ca.1771–1839), veteran of the Chickamauga wars, signer of the Treaty of New Echota - John RidgeJohn RidgeJohn Ridge, born Skah-tle-loh-skee , was from a prominent family of the Cherokee Nation, then located in present-day Georgia. He married Sarah Bird Northup, of a New England family, whom he had met while studying at the Foreign Mission School in Cornwall, Connecticut...

, Skatlelohski (1792–1839), son of Major Ridge, statesman, New Echota Treaty signer - Clement V. Rogers (1839–1911), Cherokee senator, judge, cattleman, member of the Oklahoma Constitutional Convention

- Will RogersWill RogersWilliam "Will" Penn Adair Rogers was an American cowboy, comedian, humorist, social commentator, vaudeville performer, film actor, and one of the world's best-known celebrities in the 1920s and 1930s....

, Cherokee entertainer, roper, journalist, philosopher and author - John RossJohn Ross (Cherokee chief)John Ross , also known as Guwisguwi , was Principal Chief of the Cherokee Native American Nation from 1828–1866...

, Guwisguwi (1790–1866), Principal Chief in the east (during the Removal) and in the west - SequoyahSequoyahSequoyah , named in English George Gist or George Guess, was a Cherokee silversmith. In 1821 he completed his independent creation of a Cherokee syllabary, making reading and writing in Cherokee possible...

(ca. 1767–1843), inventor of the Cherokee syllabaryCherokee syllabaryThe Cherokee syllabary is a syllabary invented by Sequoyah to write the Cherokee language in the late 1810s and early 1820s. His creation of the syllabary is particularly noteworthy in that he could not previously read any script. He first experimented with logograms, but his system later developed... - Nimrod Jarrett Smith, Tsaladihi (1837–1893), Principal Chief of the Eastern Band, Civil War veteran

- William Holland ThomasWilliam Holland ThomasWilliam Holland Thomas was Principal Chief of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians and an officer in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War....

, Wil' Usdi (1805–1893), a non-Native, but adopted into the tribe; founding Principal Chief of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians - James VannJames VannJames Vann was an influential Cherokee leader, one of the triumvirate with Major Ridge and Charles R. Hicks, who led the Upper Towns of East Tennessee and North Georgia. He was the son of Wah-Li Vann, a mixed-race Cherokee woman, and a Scots fur trader...

(ca. 1765–1809), Scottish-Cherokee, highly successful businessman and veteran - Stand WatieStand WatieStand Watie , also known as Standhope Uwatie, Degataga , meaning “stand firm”), and Isaac S. Watie, was a leader of the Cherokee Nation and a brigadier general of the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War...

, Degataga (1806–1871), signer of the Treaty of New EchotaTreaty of New EchotaThe Treaty of New Echota was a treaty signed on December 29, 1835, in New Echota, Georgia by officials of the United States government and representatives of a minority Cherokee political faction, known as the Treaty Party...

, last Confederate general to surrender in the American Civil WarAmerican Civil WarThe American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...