Cherokee Nation (19th century)

Encyclopedia

The Cherokee Nation of the 19th century —an historic entity —was a legal, autonomous, tribal government in North America

existing from 1794–1906. Often referred to simply as The Nation by its inhabitants, it should not be confused with what is known today as the "modern" Cherokee Nation

. It consisted of the Cherokee

(ᏣᎳᎩ —pronounced Tsalagi or Cha-la-gee) people of the Qualla Boundary

; those who relocated voluntarily from the southeastern United States

to the Indian Territory

(circa 1820 —known as the "Old Settlers"); those who were forced by the United States

government

to relocate by way of the Trail of Tears

(1830s); Cherokee Freedmen (freed slaves); as well as many descendants of the Natchez

, the Delaware

and the Shawnee

peoples.

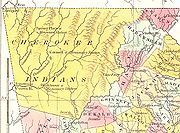

The Cherokee called themselves the Ani-Yun' wiya, meaning leading or principal people. Before 1794, the Cherokee had no standing national government. The people dwelt in "towns" located in scattered autonomous tribal areas throughout the southern Appalachia

The Cherokee called themselves the Ani-Yun' wiya, meaning leading or principal people. Before 1794, the Cherokee had no standing national government. The people dwelt in "towns" located in scattered autonomous tribal areas throughout the southern Appalachia

region. Various leaders were periodically appointed (by mutual consent of the towns) to represent the tribes to French, British and, later, American authorities as was needed. The title this leader carried among the Cherokee was "First Beloved Man" —being the true translation of the title "Uku", which the English translated as "chief

". This chief's only real function was to serve as focal point for negotiations with the encroaching Europeans, such as the case of Hanging Maw

, who was recognized as chief by the United States government, but not by the majority of Cherokee peoples.

At the end of the Chickamauga Wars (1794), Little Turkey

was recognized as "Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation

" by all the towns. At that time, Cherokee tribes could be found in lands under the jurisdiction of Georgia

, North Carolina

, South Carolina

, and the Overhill

area that was to become part of the state of Tennessee

. Also, the break-away Chickamauga

(or Lower Cherokee), under chief Dragging Canoe

(Tsiyugunsini, 1738–1792), had retreated to and now inhabited an area that would be within the future state of Alabama

.

U.S. president, George Washington

, sought to "civilize" the southeastern American Indians, through programs overseen by Indian Agent

Benjamin Hawkins

. Facilitated by the destruction of many Indian towns during the American Revolutionary War

, U.S. land agents convinced many Native Americans to abandon their historic communal-land tenure and settle on isolated farmsteads. Over-harvesting by the deerskin trade

had brought white-tailed deer

in the region to the brink of extinction; therefore, pig and cattle raising were introduced, becoming the principal sources of meat. The tribes were supplied with spinning wheel

s and cotton

-seed, and men were taught to fence and plow the land (in contrast with the traditional division where farming was considered woman's labor). Women were instructed in weaving. Eventually blacksmiths, gristmills and cotton plantations (along with slave labor) were established.

Succeeding Little Turkey as Principal Chief were Black Fox

(1801–1811) and Pathkiller

(1811–1827), both former warriors of Dragging Canoe. "The separation", which was the period after 1776 when the Chickamauga had removed themselves from the other tribes which were in close proximity to the Anglo-American settlements, officially ended at the reunification council of 1809.

The important Chickamauga War veterans of the time, James Vann

(a successful Scot-Cherokee businessman) and his two protégés, The Ridge

(also called Ganundalegi or "Major" Ridge) and Charles R. Hicks

made up the 'Cherokee Triumvirate' —advocating acculturation

of the people, formal education of the young, and the introduction of modern farming methods. In 1801 they even invited Moravian missionaries from North Carolina

to teach Christianity and the 'arts of civilized life.' The Moravian, and later Congregationalist, missionaries ran boarding schools, with a select few students chosen to be educated at the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions

school in Connecticut

.

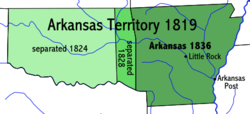

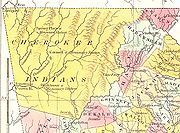

In 1802, the U.S. federal government

promised to extinguish Native American

titles to internal Georgia lands in return for the state's formal cession

of its unincorporated western claim (which would then became part of the Mississippi Territory

). In 1815, the US government established a Cherokee Reservation

in the Arkansaw district of the Missouri Territory

to convince the Cherokee to move voluntarily. The reservation boundaries extended from north of the Arkansas River

to the southern bank of the White River

. The Cherokee on this reservation became known as the "Old Settlers".

Additional treaties signed with the U.S., in 1817 and 1819, exchanged remaining Cherokee lands in Georgia (north of the Hiwassee River

) for lands in the Arkansaw Territory west of the Mississippi River

. A majority of the remaining Cherokee resisted theses treaties and refused to leave their lands east of the Mississippi. Finally, in 1830, the United States Congress

enacted the Indian Removal Act

to bolster the treaties and forcibly free up title to the sought over state lands. At this time, one-third of the remaining Native Americans left voluntarily, especially because now the act was being enforced by government troops and the Georgia militia.

Most of the settlements were established in the area around the western capitol of Tahlontiskee (near present day Gore, Oklahoma

).

The Cherokee Nation—East had adopted a written constitution in 1827 creating a government with three branches: legislative, executive, and judicial. The Principal Chief was elected by the National Council, which was the legislature of the Nation. A similar constitution was adopted by the Cherokee Nation—West in 1833. The Constitution of the reunited Cherokee Nation was ratified at Tahlequah, Oklahoma

The Cherokee Nation—East had adopted a written constitution in 1827 creating a government with three branches: legislative, executive, and judicial. The Principal Chief was elected by the National Council, which was the legislature of the Nation. A similar constitution was adopted by the Cherokee Nation—West in 1833. The Constitution of the reunited Cherokee Nation was ratified at Tahlequah, Oklahoma

on September 6, 1839, at the conclusion of "The Removal

". The signing is commemorated every Labor Day

weekend, and is a national holiday

for the Cherokee people.

—an important Cherokee town and cultural center located in present-day Tellico Plains, Tennessee —which was one of the largest Cherokee towns ever established.) The Cherokee National Capitol building was established here in 1869. It was declared a National Historic Landmark

in 1961.

Indications of Cherokee and Native American influence are easily found in and about Tahlequah. For instance, street signs appear in the Cherokee language —in the syllabary alphabet

created by Sequoyah

(ca. 1767–1843) —as well as in English.

The Trans-Mississippi area, which included the Cherokee Nation–West, hosted numerous skirmishes and seven officially recognized battles involving Native American units allied with the Confederate States of America, Native Americans loyal to the United States government, as well as Union and Confederate troops. Hold-out Confederate Brig. General Stand Watie

The Trans-Mississippi area, which included the Cherokee Nation–West, hosted numerous skirmishes and seven officially recognized battles involving Native American units allied with the Confederate States of America, Native Americans loyal to the United States government, as well as Union and Confederate troops. Hold-out Confederate Brig. General Stand Watie

raided Union positions in the Indian Territory with his 1st Cherokee Mounted Rifles

regiment well after the Confederacy had abandoned the area. He became the last Confederate General to surrender —on June 25, 1865.

The main body of the Cherokee people had sided with the Confederacy

during the American Civil War

. As such, they were subject to the same post-war constitutional restraints put on the holding of slaves as was the rest of the south. The area also became part of the reconstruction of the southern United States.

(both residing in the Indian Territory by the 1840s), and the Cherokee Nation–East (Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians

) —the three federally recognized tribes of Cherokees.

. By the mid-eighteenth century, the Natchez people were defeated and dispersed. Many survivors had been sold (by the French) into slavery in the West Indies. Others took refuge with allied tribes, one of which was the Cherokee.

with the Seneca people in July of 1831. The term "Loyal" came from their serving in the Union army during the American Civil War

. European-Americans settled on their lands, so in 1869, the Cherokee Nation and Loyal Shawnee agreed that 722 of the Shawnee would gain Cherokee citizenship. They settled in Craig

and Rogers Counties

.

slaves that had been owned by citizens of the Cherokee Nation during the Antebellum Period, and were first guaranteed Cherokee citizenship under a treaty with the United States following the Civil War (1866). When President Lincoln

freed the slaves, his Emancipation Proclamation

granted citizenship to all freedmen in the Confederate States, including those held by the Cherokee. In reaching peace with the Cherokee —who had sided with the Confederacy

—the U.S. government required that they also would abide by these constitutional principles.

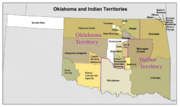

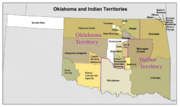

From 1898–1906, beginning with the Curtis Act of 1898

, the US federal government set about the dismantling of the Cherokee Nation's governmental and civic institutions, in preparation for the incorporation of the Indian Territory

into the new state of Oklahoma

. Thereafter, the structure and function of the tribal government was not clearly defined.

The tribal government of the Cherokee Nation was officially dissolved in 1906. Afterward, the U.S. federal government periodically appointed chiefs to the Cherokee Nation, often just long enough to sign treaties.

After several decades of this, the Cherokee people recognized that they needed leadership, and to that end, they convened a general convention on 8 August 1938, in Fairfield, Oklahoma

) to elect a new Chief, and reconstitute a modern, Cherokee Nation

.

North America

North America is a continent wholly within the Northern Hemisphere and almost wholly within the Western Hemisphere. It is also considered a northern subcontinent of the Americas...

existing from 1794–1906. Often referred to simply as The Nation by its inhabitants, it should not be confused with what is known today as the "modern" Cherokee Nation

Cherokee Nation

The Cherokee Nation is the largest of three Cherokee federally recognized tribes in the United States. It was established in the 20th century, and includes people descended from members of the old Cherokee Nation who relocated voluntarily from the Southeast to Indian Territory and Cherokees who...

. It consisted of the Cherokee

Cherokee

The Cherokee are a Native American people historically settled in the Southeastern United States . Linguistically, they are part of the Iroquoian language family...

(ᏣᎳᎩ —pronounced Tsalagi or Cha-la-gee) people of the Qualla Boundary

Qualla Boundary

The Qualla Boundary is the territory where the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians reside in western North Carolina.-Location:...

; those who relocated voluntarily from the southeastern United States

Southeastern United States

The Southeastern United States, colloquially referred to as the Southeast, is the eastern portion of the Southern United States. It is one of the most populous regions in the United States of America....

to the Indian Territory

Indian Territory

The Indian Territory, also known as the Indian Territories and the Indian Country, was land set aside within the United States for the settlement of American Indians...

(circa 1820 —known as the "Old Settlers"); those who were forced by the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

government

Federal government of the United States

The federal government of the United States is the national government of the constitutional republic of fifty states that is the United States of America. The federal government comprises three distinct branches of government: a legislative, an executive and a judiciary. These branches and...

to relocate by way of the Trail of Tears

Trail of Tears

The Trail of Tears is a name given to the forced relocation and movement of Native American nations from southeastern parts of the United States following the Indian Removal Act of 1830...

(1830s); Cherokee Freedmen (freed slaves); as well as many descendants of the Natchez

Natchez people

The Natchez are a Native American people who originally lived in the Natchez Bluffs area, near the present-day city of Natchez, Mississippi. They spoke a language isolate that has no known close relatives, although it may be very distantly related to the Muskogean languages of the Creek...

, the Delaware

Delaware Tribe of Indians

The Delaware Tribe of Indians, sometimes called the Eastern Delaware, based in Bartlesville, Oklahoma, is one of two federally recognized tribe of Lenape Indians, along with the Delaware Nation based in Anadarko, Oklahoma.-History:...

and the Shawnee

Shawnee

The Shawnee, Shaawanwaki, Shaawanooki and Shaawanowi lenaweeki, are an Algonquian-speaking people native to North America. Historically they inhabited the areas of Ohio, Virginia, West Virginia, Western Maryland, Kentucky, Indiana, and Pennsylvania...

peoples.

History

Appalachia

Appalachia is a term used to describe a cultural region in the eastern United States that stretches from the Southern Tier of New York state to northern Alabama, Mississippi, and Georgia. While the Appalachian Mountains stretch from Belle Isle in Canada to Cheaha Mountain in the U.S...

region. Various leaders were periodically appointed (by mutual consent of the towns) to represent the tribes to French, British and, later, American authorities as was needed. The title this leader carried among the Cherokee was "First Beloved Man" —being the true translation of the title "Uku", which the English translated as "chief

Tribal chief

A tribal chief is the leader of a tribal society or chiefdom. Tribal societies with social stratification under a single leader emerged in the Neolithic period out of earlier tribal structures with little stratification, and they remained prevalent throughout the Iron Age.In the case of ...

". This chief's only real function was to serve as focal point for negotiations with the encroaching Europeans, such as the case of Hanging Maw

Hanging Maw

Hanging Maw, or Uskwa'li-gu'ta in Cherokee, was the leading chief of the Overhill Cherokee from 1788 to 1794. They were located in present-day Tennessee...

, who was recognized as chief by the United States government, but not by the majority of Cherokee peoples.

At the end of the Chickamauga Wars (1794), Little Turkey

Little Turkey

Little Turkey was elected First Beloved Man by the general council of the Cherokee upon the move of the council's seat to Ustanali on the Conasauga River following the murder of Corntassel in 1788...

was recognized as "Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation

Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation

Principal Chief is today the title of the chief executives of the Cherokee Nation, of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, and of the United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians, the three federally recognized tribes of Cherokee. In the eighteenth century, when the people were organized by clans and...

" by all the towns. At that time, Cherokee tribes could be found in lands under the jurisdiction of Georgia

Georgia (U.S. state)

Georgia is a state located in the southeastern United States. It was established in 1732, the last of the original Thirteen Colonies. The state is named after King George II of Great Britain. Georgia was the fourth state to ratify the United States Constitution, on January 2, 1788...

, North Carolina

North Carolina

North Carolina is a state located in the southeastern United States. The state borders South Carolina and Georgia to the south, Tennessee to the west and Virginia to the north. North Carolina contains 100 counties. Its capital is Raleigh, and its largest city is Charlotte...

, South Carolina

South Carolina

South Carolina is a state in the Deep South of the United States that borders Georgia to the south, North Carolina to the north, and the Atlantic Ocean to the east. Originally part of the Province of Carolina, the Province of South Carolina was one of the 13 colonies that declared independence...

, and the Overhill

Overhill Cherokee

The term Overhill Cherokee refers to the former Cherokee settlements located in what is now Tennessee in the southeastern United States. The name was given by 18th century European traders and explorers who had to cross the Appalachian Mountains to reach these settlements when traveling from...

area that was to become part of the state of Tennessee

Tennessee

Tennessee is a U.S. state located in the Southeastern United States. It has a population of 6,346,105, making it the nation's 17th-largest state by population, and covers , making it the 36th-largest by total land area...

. Also, the break-away Chickamauga

Chickamauga Indian

The Chickamauga or Lower Cherokee, were a band of Cherokee who supported Great Britain at the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War. They were followers of the Cherokee chief Dragging Canoe...

(or Lower Cherokee), under chief Dragging Canoe

Dragging Canoe

Tsiyu Gansini , "He is dragging his canoe", known to whites as Dragging Canoe, was a Cherokee war chief who led a band of Cherokee against colonists and United States settlers...

(Tsiyugunsini, 1738–1792), had retreated to and now inhabited an area that would be within the future state of Alabama

Alabama

Alabama is a state located in the southeastern region of the United States. It is bordered by Tennessee to the north, Georgia to the east, Florida and the Gulf of Mexico to the south, and Mississippi to the west. Alabama ranks 30th in total land area and ranks second in the size of its inland...

.

U.S. president, George Washington

George Washington

George Washington was the dominant military and political leader of the new United States of America from 1775 to 1799. He led the American victory over Great Britain in the American Revolutionary War as commander-in-chief of the Continental Army from 1775 to 1783, and presided over the writing of...

, sought to "civilize" the southeastern American Indians, through programs overseen by Indian Agent

Indian agent

In United States history, an Indian agent was an individual authorized to interact with Native American tribes on behalf of the U.S. government.-Indian agents:*Leander Clark was agent for the Sac and Fox in Iowa beginning in 1866....

Benjamin Hawkins

Benjamin Hawkins

Benjamin Hawkins was an American planter, statesman, and United States Indian agent . He was a delegate to the Continental Congress and a United States Senator from North Carolina, having grown up among the planter elite...

. Facilitated by the destruction of many Indian towns during the American Revolutionary War

American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War , the American War of Independence, or simply the Revolutionary War, began as a war between the Kingdom of Great Britain and thirteen British colonies in North America, and ended in a global war between several European great powers.The war was the result of the...

, U.S. land agents convinced many Native Americans to abandon their historic communal-land tenure and settle on isolated farmsteads. Over-harvesting by the deerskin trade

Deerskin trade

The deerskin trade between Colonial America and the Native Americans was one of the most important trading relationships between Europeans and Native Americans, especially in the southeast. It was a form of the fur trade, but less known, since deer skins were not as valuable as furs from the north...

had brought white-tailed deer

White-tailed Deer

The white-tailed deer , also known as the Virginia deer or simply as the whitetail, is a medium-sized deer native to the United States , Canada, Mexico, Central America, and South America as far south as Peru...

in the region to the brink of extinction; therefore, pig and cattle raising were introduced, becoming the principal sources of meat. The tribes were supplied with spinning wheel

Spinning wheel

A spinning wheel is a device for spinning thread or yarn from natural or synthetic fibers. Spinning wheels appeared in Asia, probably in the 11th century, and very gradually replaced hand spinning with spindle and distaff...

s and cotton

Cotton

Cotton is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective capsule, around the seeds of cotton plants of the genus Gossypium. The fiber is almost pure cellulose. The botanical purpose of cotton fiber is to aid in seed dispersal....

-seed, and men were taught to fence and plow the land (in contrast with the traditional division where farming was considered woman's labor). Women were instructed in weaving. Eventually blacksmiths, gristmills and cotton plantations (along with slave labor) were established.

Succeeding Little Turkey as Principal Chief were Black Fox

Black Fox (chief)

Black Fox was a brother-in-law of Dragging Canoe. He was a signatory of the Holston Treaty . Black Fox was chief of Ustanali town and was the Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation from 1801 to 1811. He was the leading negotiator for the Cherokee with the United States federal government during...

(1801–1811) and Pathkiller

Pathkiller

Pathkiller, , fought in the Revolutionary War for Britain, then in the Chickamauga Wars against American frontiersmen . He was the Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation from 1811-1827. Pathkiller, a fullblood, "unacculturated" Cherokee, was the last individual from a conservative background to...

(1811–1827), both former warriors of Dragging Canoe. "The separation", which was the period after 1776 when the Chickamauga had removed themselves from the other tribes which were in close proximity to the Anglo-American settlements, officially ended at the reunification council of 1809.

The important Chickamauga War veterans of the time, James Vann

James Vann

James Vann was an influential Cherokee leader, one of the triumvirate with Major Ridge and Charles R. Hicks, who led the Upper Towns of East Tennessee and North Georgia. He was the son of Wah-Li Vann, a mixed-race Cherokee woman, and a Scots fur trader...

(a successful Scot-Cherokee businessman) and his two protégés, The Ridge

Major Ridge

Major Ridge, The Ridge was a Cherokee Indian member of the tribal council, a lawmaker, and a leader. He was a veteran of the Chickamauga Wars, the Creek War, and the First Seminole War.Along with Charles R...

(also called Ganundalegi or "Major" Ridge) and Charles R. Hicks

Charles R. Hicks

Charles Renatus Hicks was one of the most important Cherokee leaders in the early 19th century; together with James Vann and Major Ridge, he was one of a triumvirate of younger chiefs urging the tribe to acculturate to European-American ways and supported a Moravian mission school to educate the...

made up the 'Cherokee Triumvirate' —advocating acculturation

Acculturation

Acculturation explains the process of cultural and psychological change that results following meeting between cultures. The effects of acculturation can be seen at multiple levels in both interacting cultures. At the group level, acculturation often results in changes to culture, customs, and...

of the people, formal education of the young, and the introduction of modern farming methods. In 1801 they even invited Moravian missionaries from North Carolina

North Carolina

North Carolina is a state located in the southeastern United States. The state borders South Carolina and Georgia to the south, Tennessee to the west and Virginia to the north. North Carolina contains 100 counties. Its capital is Raleigh, and its largest city is Charlotte...

to teach Christianity and the 'arts of civilized life.' The Moravian, and later Congregationalist, missionaries ran boarding schools, with a select few students chosen to be educated at the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions

American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions

The American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions was the first American Christian foreign mission agency. It was proposed in 1810 by recent graduates of Williams College and officially chartered in 1812. In 1961 it merged with other societies to form the United Church Board for World...

school in Connecticut

Connecticut

Connecticut is a state in the New England region of the northeastern United States. It is bordered by Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, and the state of New York to the west and the south .Connecticut is named for the Connecticut River, the major U.S. river that approximately...

.

The Removal

In 1802, the U.S. federal government

Federal government of the United States

The federal government of the United States is the national government of the constitutional republic of fifty states that is the United States of America. The federal government comprises three distinct branches of government: a legislative, an executive and a judiciary. These branches and...

promised to extinguish Native American

Native Americans in the United States

Native Americans in the United States are the indigenous peoples in North America within the boundaries of the present-day continental United States, parts of Alaska, and the island state of Hawaii. They are composed of numerous, distinct tribes, states, and ethnic groups, many of which survive as...

titles to internal Georgia lands in return for the state's formal cession

Cession

The act of Cession, or to cede, is the assignment of property to another entity. In international law it commonly refers to land transferred by treaty...

of its unincorporated western claim (which would then became part of the Mississippi Territory

Mississippi Territory

The Territory of Mississippi was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from April 7, 1798, until December 10, 1817, when the final extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the state of Mississippi....

). In 1815, the US government established a Cherokee Reservation

Indian reservation

An American Indian reservation is an area of land managed by a Native American tribe under the United States Department of the Interior's Bureau of Indian Affairs...

in the Arkansaw district of the Missouri Territory

Missouri Territory

The Territory of Missouri was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from June 4, 1812 until August 10, 1821, when the southeastern portion of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Missouri.-History:...

to convince the Cherokee to move voluntarily. The reservation boundaries extended from north of the Arkansas River

Arkansas River

The Arkansas River is a major tributary of the Mississippi River. The Arkansas generally flows to the east and southeast as it traverses the U.S. states of Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Arkansas. The river's initial basin starts in the Western United States in Colorado, specifically the Arkansas...

to the southern bank of the White River

White River (Arkansas)

The White River is a 722-mile long river that flows through the U.S. states of Arkansas and Missouri.-Course:The source of the White River is in the Boston Mountains of northwest Arkansas, in the Ozark-St. Francis National Forest southeast of Fayetteville...

. The Cherokee on this reservation became known as the "Old Settlers".

Additional treaties signed with the U.S., in 1817 and 1819, exchanged remaining Cherokee lands in Georgia (north of the Hiwassee River

Hiwassee River

The Hiwassee River has its headwaters on the north slope of Rocky Mountain in Towns County in northern Georgia and flows northward into North Carolina before turning westward into Tennessee, flowing into the Tennessee River a few miles west of State Route 58 in Meigs County, Tennessee...

) for lands in the Arkansaw Territory west of the Mississippi River

Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the largest river system in North America. Flowing entirely in the United States, this river rises in western Minnesota and meanders slowly southwards for to the Mississippi River Delta at the Gulf of Mexico. With its many tributaries, the Mississippi's watershed drains...

. A majority of the remaining Cherokee resisted theses treaties and refused to leave their lands east of the Mississippi. Finally, in 1830, the United States Congress

United States Congress

The United States Congress is the bicameral legislature of the federal government of the United States, consisting of the Senate and the House of Representatives. The Congress meets in the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C....

enacted the Indian Removal Act

Indian Removal Act

The Indian Removal Act was signed into law by President Andrew Jackson on May 28, 1830.The Removal Act was strongly supported in the South, where states were eager to gain access to lands inhabited by the Five Civilized Tribes. In particular, Georgia, the largest state at that time, was involved in...

to bolster the treaties and forcibly free up title to the sought over state lands. At this time, one-third of the remaining Native Americans left voluntarily, especially because now the act was being enforced by government troops and the Georgia militia.

Most of the settlements were established in the area around the western capitol of Tahlontiskee (near present day Gore, Oklahoma

Gore, Oklahoma

Gore is a town in Sequoyah County, Oklahoma, United States. It is part of the Fort Smith, Arkansas-Oklahoma Metropolitan Statistical Area. The population was 850 at the 2000 census...

).

Constitutional governments

Tahlequah, Oklahoma

Tahlequah is a city in Cherokee County, Oklahoma, United States located at the foothills of the Ozark Mountains. It was founded as a capital of the original Cherokee Nation in 1838 to welcome those Cherokee forced west on the Trail of Tears. The city's population was 15,753 at the 2010 census. It...

on September 6, 1839, at the conclusion of "The Removal

Trail of Tears

The Trail of Tears is a name given to the forced relocation and movement of Native American nations from southeastern parts of the United States following the Indian Removal Act of 1830...

". The signing is commemorated every Labor Day

Labor Day

Labor Day is a United States federal holiday observed on the first Monday in September that celebrates the economic and social contributions of workers.-History:...

weekend, and is a national holiday

National Day

The National Day is a designated date on which celebrations mark the nationhood of a nation or non-sovereign country. This nationhood can be symbolized by the date of independence, of becoming republic or a significant date for a patron saint or a ruler . Often the day is not called "National Day"...

for the Cherokee people.

A new home

Founded in 1838, Tahlequah was created to be the new capitol of a united Cherokee Nation. (Named after Great TellicoGreat Tellico

Great Tellico was a Cherokee town at the site of present-day Tellico Plains, Tennessee, where the Tellico River emerges from the Appalachian Mountains. Great Tellico was one of the largest Cherokee towns in the region, and had a sister town nearby named Chatuga. Its name in Cherokee is more...

—an important Cherokee town and cultural center located in present-day Tellico Plains, Tennessee —which was one of the largest Cherokee towns ever established.) The Cherokee National Capitol building was established here in 1869. It was declared a National Historic Landmark

National Historic Landmark

A National Historic Landmark is a building, site, structure, object, or district, that is officially recognized by the United States government for its historical significance...

in 1961.

Indications of Cherokee and Native American influence are easily found in and about Tahlequah. For instance, street signs appear in the Cherokee language —in the syllabary alphabet

Cherokee syllabary

The Cherokee syllabary is a syllabary invented by Sequoyah to write the Cherokee language in the late 1810s and early 1820s. His creation of the syllabary is particularly noteworthy in that he could not previously read any script. He first experimented with logograms, but his system later developed...

created by Sequoyah

Sequoyah

Sequoyah , named in English George Gist or George Guess, was a Cherokee silversmith. In 1821 he completed his independent creation of a Cherokee syllabary, making reading and writing in Cherokee possible...

(ca. 1767–1843) —as well as in English.

Civil War and reconstruction

Stand Watie

Stand Watie , also known as Standhope Uwatie, Degataga , meaning “stand firm”), and Isaac S. Watie, was a leader of the Cherokee Nation and a brigadier general of the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War...

raided Union positions in the Indian Territory with his 1st Cherokee Mounted Rifles

1st Cherokee Mounted Rifles

The 1st Cherokee Mounted Rifles was a Confederate States Army regiment which fought in the Indian Territory during the American Civil War. One of its commanders was Stand Watie....

regiment well after the Confederacy had abandoned the area. He became the last Confederate General to surrender —on June 25, 1865.

The main body of the Cherokee people had sided with the Confederacy

Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America was a government set up from 1861 to 1865 by 11 Southern slave states of the United States of America that had declared their secession from the U.S...

during the American Civil War

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

. As such, they were subject to the same post-war constitutional restraints put on the holding of slaves as was the rest of the south. The area also became part of the reconstruction of the southern United States.

People

The Nation was made up of scattered peoples mostly living in the Cherokee Nation–West and the United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee IndiansUnited Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians

The United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians in Oklahoma is a federally recognized tribe of Cherokee Indians headquartered in Tahlequah, Oklahoma. The United Keetoowah are also referred to as the UKB...

(both residing in the Indian Territory by the 1840s), and the Cherokee Nation–East (Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians

Qualla Boundary

The Qualla Boundary is the territory where the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians reside in western North Carolina.-Location:...

) —the three federally recognized tribes of Cherokees.

Natchez people

The Natchez are a Native American people who originally lived in the Natchez Bluffs area, near the present-day city of Natchez, MississippiNatchez, Mississippi

Natchez is the county seat of Adams County, Mississippi, United States. With a total population of 18,464 , it is the largest community and the only incorporated municipality within Adams County...

. By the mid-eighteenth century, the Natchez people were defeated and dispersed. Many survivors had been sold (by the French) into slavery in the West Indies. Others took refuge with allied tribes, one of which was the Cherokee.

The Shawnee

Known as the Loyal Shawnee or Cherokee Shawnee, one band of Shawnee people relocated to Indian TerritoryIndian Territory

The Indian Territory, also known as the Indian Territories and the Indian Country, was land set aside within the United States for the settlement of American Indians...

with the Seneca people in July of 1831. The term "Loyal" came from their serving in the Union army during the American Civil War

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

. European-Americans settled on their lands, so in 1869, the Cherokee Nation and Loyal Shawnee agreed that 722 of the Shawnee would gain Cherokee citizenship. They settled in Craig

Craig County, Oklahoma

Craig County is a county located in the U.S. state of Oklahoma. As of 2010, the population was 15,029, a gain of 0.5 percent from 14,950 in 2000. Its county seat is Vinita.Craig County was organized in 1907.-History:...

and Rogers Counties

Rogers County, Oklahoma

Rogers County is a county located in the U.S. state of Oklahoma. As of 2010, the population was 86,905. Its county seat is Claremore. The county was originally created in 1906 and named Cooweescoowee...

.

Cherokee freedmen

The Cherokee freedmen, were freed African AmericanAfrican American

African Americans are citizens or residents of the United States who have at least partial ancestry from any of the native populations of Sub-Saharan Africa and are the direct descendants of enslaved Africans within the boundaries of the present United States...

slaves that had been owned by citizens of the Cherokee Nation during the Antebellum Period, and were first guaranteed Cherokee citizenship under a treaty with the United States following the Civil War (1866). When President Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln was the 16th President of the United States, serving from March 1861 until his assassination in April 1865. He successfully led his country through a great constitutional, military and moral crisis – the American Civil War – preserving the Union, while ending slavery, and...

freed the slaves, his Emancipation Proclamation

Emancipation Proclamation

The Emancipation Proclamation is an executive order issued by United States President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, during the American Civil War using his war powers. It proclaimed the freedom of 3.1 million of the nation's 4 million slaves, and immediately freed 50,000 of them, with nearly...

granted citizenship to all freedmen in the Confederate States, including those held by the Cherokee. In reaching peace with the Cherokee —who had sided with the Confederacy

Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America was a government set up from 1861 to 1865 by 11 Southern slave states of the United States of America that had declared their secession from the U.S...

—the U.S. government required that they also would abide by these constitutional principles.

The Delaware

The Delaware, who were then residing in the northeast area of the Indian Territory, united with the Cherokee Nation in 1867. The Delaware Tribes operated autonomously within the lands of the Cherokee Nation.Nation's demise

From 1898–1906, beginning with the Curtis Act of 1898

Curtis Act of 1898

The Curtis Act of 1898 was an amendment to the United States Dawes Act that brought about the allotment process of lands of the Five Civilized Tribes of Indian Territory: the Choctaw, Chickasaw, Muscogee, Cherokee, and Seminole...

, the US federal government set about the dismantling of the Cherokee Nation's governmental and civic institutions, in preparation for the incorporation of the Indian Territory

Indian Territory

The Indian Territory, also known as the Indian Territories and the Indian Country, was land set aside within the United States for the settlement of American Indians...

into the new state of Oklahoma

Oklahoma

Oklahoma is a state located in the South Central region of the United States of America. With an estimated 3,751,351 residents as of the 2010 census and a land area of 68,667 square miles , Oklahoma is the 28th most populous and 20th-largest state...

. Thereafter, the structure and function of the tribal government was not clearly defined.

The tribal government of the Cherokee Nation was officially dissolved in 1906. Afterward, the U.S. federal government periodically appointed chiefs to the Cherokee Nation, often just long enough to sign treaties.

After several decades of this, the Cherokee people recognized that they needed leadership, and to that end, they convened a general convention on 8 August 1938, in Fairfield, Oklahoma

Fairfield, Oklahoma

Fairfield is a census-designated place in Adair County, Oklahoma, United States. The population was 367 at the 2000 census.-Geography:Fairfield is located at ....

) to elect a new Chief, and reconstitute a modern, Cherokee Nation

Cherokee Nation

The Cherokee Nation is the largest of three Cherokee federally recognized tribes in the United States. It was established in the 20th century, and includes people descended from members of the old Cherokee Nation who relocated voluntarily from the Southeast to Indian Territory and Cherokees who...

.

Important members of the historic Cherokee Nation

This list of historic people only includes documented Cherokees not mentioned in the main article.- William Penn AdairWilliam Penn AdairWilliam Penn Adair was a Cherokee leader and Confederate colonel.-Background:William Penn Adair was born on April 15, 1830 in the old Cherokee Nation in New Echota, Georgia. His parents were George Washington Adair and Martha Adair. He attended Cherokee schools in Indian Territory, studying law....

(1830–1880), Cherokee senator and diplomat, Confederate colonel. - Elias BoudinotElias Boudinot (Cherokee)Elias Boudinot , was a member of an important Cherokee family in present-day Georgia. They believed that rapid acculturation was critical to Cherokee survival. In 1828 Boudinot became the editor of the Cherokee Phoenix, which was published in Cherokee and English...

, Galagina (1802–1839), statesman, orator, and editor, founded first Cherokee newspaper, Cherokee PhoenixCherokee PhoenixThe Cherokee Phoenix was the first newspaper published by Native Americans in the United States and the first published in a Native American language. The first issue was published in English and Cherokee on February 21, 1828, in New Echota, capital of the Cherokee Nation . The paper continued...

. - Ned ChristieNed ChristieNed Christie , also known as NeDe WaDe , was a Cherokee statesman. Ned was a member of the executive council in the Cherokee Nation senate, and served as one of three advisers to Chief Bushyhead...

(1852–1892), statesman, Cherokee Nation senator, infamous outlaw - Rear Admiral Joseph J. ClarkJoseph J. ClarkAdmiral Joseph James "Jocko" Clark, USN was an admiral in the United States Navy, who commanded aircraft carriers during World War II. A native of Oklahoma, Clark was a member of the Cherokee tribe...

(1893–1971), United States Navy, highest ranking Native American in the US military. - DoubleheadDoubleheadDoublehead or Incalatanga , was one of the most feared warriors of the Cherokee during the Chickamauga Wars. In 1788, his brother, Old Tassel, was chief of the Cherokee people, but was killed under a truce by frontier rangers. In 1791 Doublehead was among a delegation of Cherokees who visited U.S...

, Taltsuska (d. 1807), a war leader during the Chickamauga Wars, led the Lower Cherokee, signed land deals with the U.S. - Franklin GrittsFranklin GrittsFranklin Gritts, also known as Oau Nah Jusah, or They Have Returned, was a Cherokee artist best known for his contributions to the "Golden Era" of Native American art, both as a teacher and an artist....

, Cherokee artist taught at Haskell InstituteHaskell Indian Nations UniversityHaskell Indian Nations University is a tribal university located in Lawrence, Kansas, for members of federally recognized Native American tribes in the United States...

and served on the USS FranklinUSS FranklinUSS Franklin may refer to: was a 6-gun schooner, fitted out in 1775 and returned to the owner in 1776 was an 8-gun brig built in 1795, captured by corsairs from Tripoli in 1802, bought back by the Navy in 1805, and sold in 1807 was a 74-gun ship of the line launched in 1815 and broken up in 1852...

. - Charles R. HicksCharles R. HicksCharles Renatus Hicks was one of the most important Cherokee leaders in the early 19th century; together with James Vann and Major Ridge, he was one of a triumvirate of younger chiefs urging the tribe to acculturate to European-American ways and supported a Moravian mission school to educate the...

(d. 1827), veteran of the Red Stick WarCreek WarThe Creek War , also known as the Red Stick War and the Creek Civil War, began as a civil war within the Creek nation...

, Second Principal Chief to Pathkiller in early 17th century, de facto Principal Chief from 1813–1827. - JunaluskaJunaluskaJunaluska, or Tsunu’lahun’ski in Cherokee , was a leader of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians who reside in and around western North Carolina....

(ca. 1775–1868), veteran of the Creek War, who saved President Andrew JacksonAndrew JacksonAndrew Jackson was the seventh President of the United States . Based in frontier Tennessee, Jackson was a politician and army general who defeated the Creek Indians at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend , and the British at the Battle of New Orleans...

's life. - John RidgeJohn RidgeJohn Ridge, born Skah-tle-loh-skee , was from a prominent family of the Cherokee Nation, then located in present-day Georgia. He married Sarah Bird Northup, of a New England family, whom he had met while studying at the Foreign Mission School in Cornwall, Connecticut...

, Skatlelohski (1792–1839), son of The Ridge, statesman and New Echota Treaty signer. - John Rollin RidgeJohn Rollin RidgeJohn Rollin Ridge , a member of the Cherokee Nation, is considered the first Native American novelist.-Biography:...

, Cheesquatalawny, or "Yellow Bird" (1827–1867), grandson of Major Ridge, first Native American novelist. - Clement V. Rogers (1839–1911), Cherokee senator, judge, cattleman, member of the Oklahoma Constitutional Convention.

- Will RogersWill RogersWilliam "Will" Penn Adair Rogers was an American cowboy, comedian, humorist, social commentator, vaudeville performer, film actor, and one of the world's best-known celebrities in the 1920s and 1930s....

, (November 4, 1879 – August 15, 1935) Cherokee entertainer, roper, journalist, and author. - John RossJohn Ross (Cherokee chief)John Ross , also known as Guwisguwi , was Principal Chief of the Cherokee Native American Nation from 1828–1866...

, Guwisguwi (1790–1866), veteran of the Rec Stick War, Principal Chief in the east, during Removal, and in the west. - Nimrod Jarrett Smith, Tsaladihi (1837–1893), Principal Chief of the Eastern Band, Civil War veteran.

- Redbird SmithRedbird SmithRedbird Smith was a Cherokee traditionalist and political activist. He helped found the Nighthawk Keetoowah Society, who revitalized traditional spirituality among Cherokees from the mid-19th century to the early 20th century.-Background:...

(1850–1918), traditionalist, political activist, and chief of the Nighthawk Keetoowah Society. - William Holland ThomasWilliam Holland ThomasWilliam Holland Thomas was Principal Chief of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians and an officer in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War....

, Wil' Usdi (1805–1893), non-Native but adopted into tribe, founding Principal Chief of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, commanding officer of Thomas Legion of Cherokee Indians and Highlanders. - Nancy WardNancy WardNanyehi , known in English as Nancy Ward was a Ghigau, or Beloved Woman of the Cherokee Nation, which meant that she was allowed to sit in councils and to make decisions, along with the other Beloved Women, on pardons...

, Nanye-hi (ca. 1736–1822/4), Beloved Woman, diplomat. - Stand WatieStand WatieStand Watie , also known as Standhope Uwatie, Degataga , meaning “stand firm”), and Isaac S. Watie, was a leader of the Cherokee Nation and a brigadier general of the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War...

, Degataga (1806–1871), signer of the Treaty of New Echota, last Confederate general to surrender in the American Civil War as commanding officer of the First Indian Brigade of the Army of Trans-MississippiTrans-MississippiThe Trans-Mississippi was the geographic area west of the Mississippi River during the 19th century, containing the states of Arkansas, Louisiana, Missouri and Texas, and the Indian Territory . The term was especially used by the Confederate States of America as the designation for the theater of...

.

See also

- Cherokee languageCherokee languageCherokee is an Iroquoian language spoken by the Cherokee people which uses a unique syllabary writing system. It is the only Southern Iroquoian language that remains spoken. Cherokee is a polysynthetic language.-North American etymology:...

- Cherokee historyCherokee historyCherokee history draws upon the oral traditions and written history of the Cherokee people, who are currently enrolled in the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, Cherokee Nation, and United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians, living predominantly in North Carolina and Oklahoma.-Origins:There are two...

- Cherokee military historyCherokee military historyThe Cherokee people from the Southeastern United States and later Oklahoma and surrounding areas have a long military history. Since European contact, it has been documented through European records. Tribes and bands had numerous conflicts in the 18th century with European colonizing forces,...

- State of SequoyahState of SequoyahThe State of Sequoyah was the proposed name for a state to be established in the eastern part of present-day Oklahoma. In 1905, faced by proposals to end their tribal governments, Native Americans of the Five Civilized Tribes in Indian Territory proposed such a state as a means to retain some...

- Indian Territory in the American Civil WarIndian Territory in the American Civil WarDuring the American Civil War, Indian Territory occupied most of what is now the U.S. state of Oklahoma and served as an unorganized region set aside for Native American tribes of the Southeastern United States; they had been removed from their lands...

External links

- Tsalagi resources; A Few Words in Cherokee/Tsalagi

- Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, official site

- United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians, official site

- Museum of the Cherokee Indian, Cherokee, NC

- Cherokee Heritage Center, Park Hill, OK

- Cherokee article, Oklahoma Historical Society Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture