Barringer Hill

Encyclopedia

Barringer Hill is a geological and mineralogical site in central Texas. It lies on the former west side of the Colorado river

, beneath Lake Buchanan, about 22 miles (35.4 km) northeast of the town of Llano

. The hill consists of a pegmatite

and geologically, lies near the eastern edge of the Central Mineral Region in the Texas Hill Country

. It is named for John Baringer, who discovered in it large amounts of gadolinite

about 1887 (Hess).

from a mineralogical standpoint. Described by the United States Geological Survey

as one of the greatest deposits of rare-earth minerals in the world, the pegmatite

was the first place geologists discovered fergusonite

, monofergusonite, thorogummite, yttrialite

, and nivenite. The pegmatite is centrally located in the Lone Grove pluton

, a 1.6 Ga old rapakavi granite

, intruded into Valley Spring Gneiss. Geologic evidence suggests the pluton's emplacement as a rather shallow intrusion of magma

, possibly in a sub-caldera

type situation. An original depth of five to seven kilometers may be assumed for the present level of exposure (Denney). Prior to mining

, the hill was described as 40 feet (12.2 m) tall by about 100 feet (30.5 m) wide and 250 feet (76.2 m) long. Hess describes the intrusion being surrounded by a graphic granite of peculiar beauty and definite structure, being more like a text-book illustration. A central quartz

mass was described more than 40 ft (12.2 m) across, with distinct white bands, from one-eighth to one-half inch wide. Within the white bands were found fluid inclusions and bubbles that moved only slowly when the specimen was tilted. Between these bands the quartz is glassy and clear. At one place a vug

was found large enough for a man to enter, lined with smoky quartz crystals reaching 1000 lb (500 kg) or more in weight. A large crystal of smoky quartz was removed that weighed over six hundred pounds (270 kg). It was 43 inches (1,092.2 mm) high and 28 inches (711.2 mm) broad and 15 inches (381 mm) thick (1090 by 710 by 380 mm). The feldspar

consisted of an intergrowth of microcline

and albite

, of a brownish flesh color, and occurred in large masses reaching over 30 feet (9.1 m) in diameter (Hess).

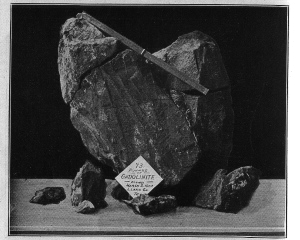

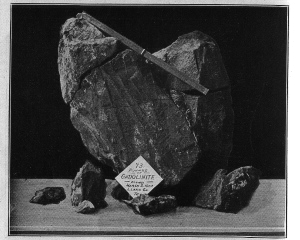

Of the 47 minerals discovered at Barringer Hill, gadolinite

Of the 47 minerals discovered at Barringer Hill, gadolinite

, a radioactive form of yttria, triggered the most interest at the time. This greenish-black ore had previously only been found in small amounts in Russia

and Norway

. Because of its economic potential as a material for light filaments, both Thomas Edison

and George Westinghouse

attempted to obtain the hill, with the Piedmont Mining Company, which was owned by Edison, winning out in 1889. In 1903, German chemist Walther Nernst

, who later became famous for discovering the Third Law of Thermodynamics

, was working for Westinghouse when he developed a street light

that used raw gadolinite as a filament. The mineral species rich in yttrium-erbium

were more particularly sought after because thorium

and uranium

were not used in the "glower" of the Nernst lamp

. The Nernst Lamp Company, a subsidy of Westinghouse, then bought Barringer Hill and began mining, extracting a few hundred pounds of ytrria minerals annually for a few years. Eventually, Nernst Lamp Company ceased operations as newer technologies surpassed the lamp. The seventy-three pound group of crystals (of gadolinite), found in March 1903, was the greatest "find" of record in this mineral; but just one year later, a mass of roughly crystallized gadolinite was found, partly imbedded in the bed-rock at the northeast corner of the hill, that measured thirty-six inches long, eleven inches (279 mm) thick at the widest part, and weighed a little over two hundred pounds. It was apparently free from alteration, had specific gravity of 4.28 (taken on a very pure fragment), had a bright green chatoyancy

at certain angles, and was like glass in its broad obsidian

-like conchoidal fracture.

Masses of coarsely crystallized fluorite

Masses of coarsely crystallized fluorite

up to four hundred pounds (180 kg) weight were not rare, and some of these had very large faces of the cube

and rhombic dodecahedron

. Its color varied from dark green to puce

and purple, and colorless transparent rough crystals having remarkably perfect cleavage

were sometimes observed. Some of the fluorite was true chlorophane and exhibited a brilliant green light when strongly heated and viewed in the dark. One mass was self-luminous, at night, without heating it. Enormous crystals of orthoclase

were common, some over five feet in diameter

. Quite frequently small veins of very perfect red feldspar

crystals (highly-twinned), and upon which albite

crystals were attached, were found bordering the fluorite and penetrating it. In the feldspar, well crystallized menaccanite was sometimes observed. Yellow rutile

, of the sagenitic variety, was observed in only one instance and then upon smoky quartz crystals. Polycrase

, or an allied species, was seen implanted upon the gadolinite. Very fair amethysts were found in the west end of the hill, in cavities in the feldspar. Masses of biotite

, four feet across, were met with and always indicated the presence near-by of the rare-earth minerals. Of particular note were the unusually long radial lines projecting in many directions from the bodies of ore richest in thorium, uranium and zirconium

. Hidden named these occurrences "stars" and eagerly sought for them, as positive "pointers" to ore. At one point he noted a redness of skin and burning sensation when mining these, that he attributed to radioactivity, which was poorly understood at the time.(Hidden)

Mineral specimens from Baringer Hill eventually found their way into collections across the country, including the Houston Museum of Natural Science

, the American Museum of Natural History

in New York, Harvard University

, and the University of Texas at Austin

.

, references the site with the lyrics saying, "Lie to me if you will/at the top of Barringer Hill".

Colorado River

The Colorado River , is a river in the Southwestern United States and northwestern Mexico, approximately long, draining a part of the arid regions on the western slope of the Rocky Mountains. The watershed of the Colorado River covers in parts of seven U.S. states and two Mexican states...

, beneath Lake Buchanan, about 22 miles (35.4 km) northeast of the town of Llano

Llano, Texas

-History:Llano County was established in compliance with a February 1, 1856, state legislative act. The Llano River location was chosen in an election held on June 14, 1856, under a live oak on the south bank of the river, near the present site of Roy Inks Bridge in Llano...

. The hill consists of a pegmatite

Pegmatite

A pegmatite is a very crystalline, intrusive igneous rock composed of interlocking crystals usually larger than 2.5 cm in size; such rocks are referred to as pegmatitic....

and geologically, lies near the eastern edge of the Central Mineral Region in the Texas Hill Country

Texas Hill Country

The Texas Hill Country is a vernacular term applied to a region of Central Texas featuring tall rugged hills consisting of thin layers of soil atop limestone or granite. It also includes the Llano Uplift and the second largest granite monadnock in the United States, Enchanted Rock, which is located...

. It is named for John Baringer, who discovered in it large amounts of gadolinite

Gadolinite

Gadolinite, sometimes also known as Ytterbite, is a silicate mineral which consists principally of the silicates of cerium, lanthanum, neodymium, yttrium, beryllium, and iron with the formula 2FeBe2Si2O10...

about 1887 (Hess).

Geology and history

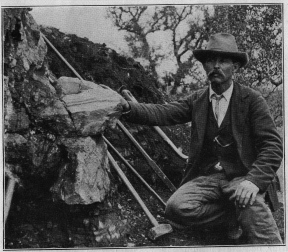

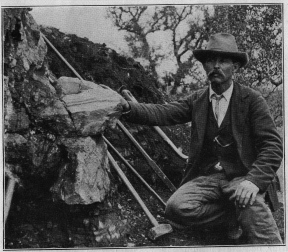

The Barringer (Baringer) pegmatite was discovered in 1887 and, until its disappearance beneath the water of Lake Buchanan in 1937, was one of the most significant places in AmericaUnited States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

from a mineralogical standpoint. Described by the United States Geological Survey

United States Geological Survey

The United States Geological Survey is a scientific agency of the United States government. The scientists of the USGS study the landscape of the United States, its natural resources, and the natural hazards that threaten it. The organization has four major science disciplines, concerning biology,...

as one of the greatest deposits of rare-earth minerals in the world, the pegmatite

Pegmatite

A pegmatite is a very crystalline, intrusive igneous rock composed of interlocking crystals usually larger than 2.5 cm in size; such rocks are referred to as pegmatitic....

was the first place geologists discovered fergusonite

Fergusonite

Fergusonite is a mineral comprising a complex oxide of various rare earth elements. The chemical formula of fergusonite species is NbO4, where RE = rare-earth elements in solid solution with Y. Yttrium is usually dominant , but sometimes Ce or Nd may predominate in molar proportion...

, monofergusonite, thorogummite, yttrialite

Yttrialite

Yttrialite or Yttrialite- is a rare yttrium thorium sorosilicate mineral with formula: 2Si2O7. It forms green to orange yellow masses with conchoidal fracture. It crystallizes in the monoclinic-prismatic crystal system. It has a Mohs hardness of 5 to 5.5 and a specific gravity of 4.58...

, and nivenite. The pegmatite is centrally located in the Lone Grove pluton

Pluton

A pluton in geology is a body of intrusive igneous rock that crystallized from magma slowly cooling below the surface of the Earth. Plutons include batholiths, dikes, sills, laccoliths, lopoliths, and other igneous bodies...

, a 1.6 Ga old rapakavi granite

Granite

Granite is a common and widely occurring type of intrusive, felsic, igneous rock. Granite usually has a medium- to coarse-grained texture. Occasionally some individual crystals are larger than the groundmass, in which case the texture is known as porphyritic. A granitic rock with a porphyritic...

, intruded into Valley Spring Gneiss. Geologic evidence suggests the pluton's emplacement as a rather shallow intrusion of magma

Magma

Magma is a mixture of molten rock, volatiles and solids that is found beneath the surface of the Earth, and is expected to exist on other terrestrial planets. Besides molten rock, magma may also contain suspended crystals and dissolved gas and sometimes also gas bubbles. Magma often collects in...

, possibly in a sub-caldera

Caldera

A caldera is a cauldron-like volcanic feature usually formed by the collapse of land following a volcanic eruption, such as the one at Yellowstone National Park in the US. They are sometimes confused with volcanic craters...

type situation. An original depth of five to seven kilometers may be assumed for the present level of exposure (Denney). Prior to mining

Mining

Mining is the extraction of valuable minerals or other geological materials from the earth, from an ore body, vein or seam. The term also includes the removal of soil. Materials recovered by mining include base metals, precious metals, iron, uranium, coal, diamonds, limestone, oil shale, rock...

, the hill was described as 40 feet (12.2 m) tall by about 100 feet (30.5 m) wide and 250 feet (76.2 m) long. Hess describes the intrusion being surrounded by a graphic granite of peculiar beauty and definite structure, being more like a text-book illustration. A central quartz

Quartz

Quartz is the second-most-abundant mineral in the Earth's continental crust, after feldspar. It is made up of a continuous framework of SiO4 silicon–oxygen tetrahedra, with each oxygen being shared between two tetrahedra, giving an overall formula SiO2. There are many different varieties of quartz,...

mass was described more than 40 ft (12.2 m) across, with distinct white bands, from one-eighth to one-half inch wide. Within the white bands were found fluid inclusions and bubbles that moved only slowly when the specimen was tilted. Between these bands the quartz is glassy and clear. At one place a vug

Vug

Vugs are small to medium-sized cavities inside rock that may be formed through a variety of processes. Most commonly cracks and fissures opened by tectonic activity are partially filled by quartz, calcite, and other secondary minerals. Open spaces within ancient collapse breccias are another...

was found large enough for a man to enter, lined with smoky quartz crystals reaching 1000 lb (500 kg) or more in weight. A large crystal of smoky quartz was removed that weighed over six hundred pounds (270 kg). It was 43 inches (1,092.2 mm) high and 28 inches (711.2 mm) broad and 15 inches (381 mm) thick (1090 by 710 by 380 mm). The feldspar

Feldspar

Feldspars are a group of rock-forming tectosilicate minerals which make up as much as 60% of the Earth's crust....

consisted of an intergrowth of microcline

Microcline

Microcline is an important igneous rock-forming tectosilicate mineral. It is a potassium-rich alkali feldspar. Microcline typically contains minor amounts of sodium. It is common in granite and pegmatites. Microcline forms during slow cooling of orthoclase; it is more stable at lower temperatures...

and albite

Albite

Albite is a plagioclase feldspar mineral. It is the sodium endmember of the plagioclase solid solution series. As such it represents a plagioclase with less than 10% anorthite content. The pure albite endmember has the formula NaAlSi3O8. It is a tectosilicate. Its color is usually pure white, hence...

, of a brownish flesh color, and occurred in large masses reaching over 30 feet (9.1 m) in diameter (Hess).

Gadolinite

Gadolinite, sometimes also known as Ytterbite, is a silicate mineral which consists principally of the silicates of cerium, lanthanum, neodymium, yttrium, beryllium, and iron with the formula 2FeBe2Si2O10...

, a radioactive form of yttria, triggered the most interest at the time. This greenish-black ore had previously only been found in small amounts in Russia

Russia

Russia or , officially known as both Russia and the Russian Federation , is a country in northern Eurasia. It is a federal semi-presidential republic, comprising 83 federal subjects...

and Norway

Norway

Norway , officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic unitary constitutional monarchy whose territory comprises the western portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula, Jan Mayen, and the Arctic archipelago of Svalbard and Bouvet Island. Norway has a total area of and a population of about 4.9 million...

. Because of its economic potential as a material for light filaments, both Thomas Edison

Thomas Edison

Thomas Alva Edison was an American inventor and businessman. He developed many devices that greatly influenced life around the world, including the phonograph, the motion picture camera, and a long-lasting, practical electric light bulb. In addition, he created the world’s first industrial...

and George Westinghouse

George Westinghouse

George Westinghouse, Jr was an American entrepreneur and engineer who invented the railway air brake and was a pioneer of the electrical industry. Westinghouse was one of Thomas Edison's main rivals in the early implementation of the American electricity system...

attempted to obtain the hill, with the Piedmont Mining Company, which was owned by Edison, winning out in 1889. In 1903, German chemist Walther Nernst

Walther Nernst

Walther Hermann Nernst FRS was a German physical chemist and physicist who is known for his theories behind the calculation of chemical affinity as embodied in the third law of thermodynamics, for which he won the 1920 Nobel Prize in chemistry...

, who later became famous for discovering the Third Law of Thermodynamics

Third law of thermodynamics

The third law of thermodynamics is a statistical law of nature regarding entropy:For other materials, the residual entropy is not necessarily zero, although it is always zero for a perfect crystal in which there is only one possible ground state.-History:...

, was working for Westinghouse when he developed a street light

Street light

A street light, lamppost, street lamp, light standard, or lamp standard is a raised source of light on the edge of a road or walkway, which is turned on or lit at a certain time every night. Modern lamps may also have light-sensitive photocells to turn them on at dusk, off at dawn, or activate...

that used raw gadolinite as a filament. The mineral species rich in yttrium-erbium

Erbium

Erbium is a chemical element in the lanthanide series, with the symbol Er and atomic number 68. A silvery-white solid metal when artificially isolated, natural erbium is always found in chemical combination with other elements on Earth...

were more particularly sought after because thorium

Thorium

Thorium is a natural radioactive chemical element with the symbol Th and atomic number 90. It was discovered in 1828 and named after Thor, the Norse god of thunder....

and uranium

Uranium

Uranium is a silvery-white metallic chemical element in the actinide series of the periodic table, with atomic number 92. It is assigned the chemical symbol U. A uranium atom has 92 protons and 92 electrons, of which 6 are valence electrons...

were not used in the "glower" of the Nernst lamp

Nernst lamp

Nernst lamps were an early form of electrically powered incandescent lamps. Nernst lamps did not use a glowing tungsten filament. Instead, they used a ceramic rod that was heated to incandescence...

. The Nernst Lamp Company, a subsidy of Westinghouse, then bought Barringer Hill and began mining, extracting a few hundred pounds of ytrria minerals annually for a few years. Eventually, Nernst Lamp Company ceased operations as newer technologies surpassed the lamp. The seventy-three pound group of crystals (of gadolinite), found in March 1903, was the greatest "find" of record in this mineral; but just one year later, a mass of roughly crystallized gadolinite was found, partly imbedded in the bed-rock at the northeast corner of the hill, that measured thirty-six inches long, eleven inches (279 mm) thick at the widest part, and weighed a little over two hundred pounds. It was apparently free from alteration, had specific gravity of 4.28 (taken on a very pure fragment), had a bright green chatoyancy

Chatoyancy

In gemology, chatoyancy , or chatoyance, is an optical reflectance effect seen in certain gemstones. Coined from the French "œil de chat," meaning "cat's eye," chatoyancy arises either from the fibrous structure of a material, as in tiger eye quartz, or from fibrous inclusions or cavities within...

at certain angles, and was like glass in its broad obsidian

Obsidian

Obsidian is a naturally occurring volcanic glass formed as an extrusive igneous rock.It is produced when felsic lava extruded from a volcano cools rapidly with minimum crystal growth...

-like conchoidal fracture.

Fluorite

Fluorite is a halide mineral composed of calcium fluoride, CaF2. It is an isometric mineral with a cubic habit, though octahedral and more complex isometric forms are not uncommon...

up to four hundred pounds (180 kg) weight were not rare, and some of these had very large faces of the cube

Cube

In geometry, a cube is a three-dimensional solid object bounded by six square faces, facets or sides, with three meeting at each vertex. The cube can also be called a regular hexahedron and is one of the five Platonic solids. It is a special kind of square prism, of rectangular parallelepiped and...

and rhombic dodecahedron

Rhombic dodecahedron

In geometry, the rhombic dodecahedron is a convex polyhedron with 12 rhombic faces. It is an Archimedean dual solid, or a Catalan solid. Its dual is the cuboctahedron.-Properties:...

. Its color varied from dark green to puce

Puce

Puce is a color that is defined as ranging from reddish-brown to purplish-brown, with the latter being the more widely accepted definition found in reputable sources. Puce is a shade of red. The Oxford English Dictionary dates the use of "puce" from 1787...

and purple, and colorless transparent rough crystals having remarkably perfect cleavage

Cleavage (crystal)

Cleavage, in mineralogy, is the tendency of crystalline materials to split along definite crystallographic structural planes. These planes of relative weakness are a result of the regular locations of atoms and ions in the crystal, which create smooth repeating surfaces that are visible both in the...

were sometimes observed. Some of the fluorite was true chlorophane and exhibited a brilliant green light when strongly heated and viewed in the dark. One mass was self-luminous, at night, without heating it. Enormous crystals of orthoclase

Orthoclase

Orthoclase is an important tectosilicate mineral which forms igneous rock. The name is from the Greek for "straight fracture," because its two cleavage planes are at right angles to each other. Alternate names are alkali feldspar and potassium feldspar...

were common, some over five feet in diameter

Diameter

In geometry, a diameter of a circle is any straight line segment that passes through the center of the circle and whose endpoints are on the circle. The diameters are the longest chords of the circle...

. Quite frequently small veins of very perfect red feldspar

Feldspar

Feldspars are a group of rock-forming tectosilicate minerals which make up as much as 60% of the Earth's crust....

crystals (highly-twinned), and upon which albite

Albite

Albite is a plagioclase feldspar mineral. It is the sodium endmember of the plagioclase solid solution series. As such it represents a plagioclase with less than 10% anorthite content. The pure albite endmember has the formula NaAlSi3O8. It is a tectosilicate. Its color is usually pure white, hence...

crystals were attached, were found bordering the fluorite and penetrating it. In the feldspar, well crystallized menaccanite was sometimes observed. Yellow rutile

Rutile

Rutile is a mineral composed primarily of titanium dioxide, TiO2.Rutile is the most common natural form of TiO2. Two rarer polymorphs of TiO2 are known:...

, of the sagenitic variety, was observed in only one instance and then upon smoky quartz crystals. Polycrase

Polycrase

Polycrase or polycrase- is a black or brown metallic complex uranium yttrium oxide mineral with formula: 2O6. It is amorphous. It has a Mohs hardness of 5 to 6 and a specific gravity of 5. It is radioactive due to its uranium content...

, or an allied species, was seen implanted upon the gadolinite. Very fair amethysts were found in the west end of the hill, in cavities in the feldspar. Masses of biotite

Biotite

Biotite is a common phyllosilicate mineral within the mica group, with the approximate chemical formula . More generally, it refers to the dark mica series, primarily a solid-solution series between the iron-endmember annite, and the magnesium-endmember phlogopite; more aluminous endmembers...

, four feet across, were met with and always indicated the presence near-by of the rare-earth minerals. Of particular note were the unusually long radial lines projecting in many directions from the bodies of ore richest in thorium, uranium and zirconium

Zirconium

Zirconium is a chemical element with the symbol Zr and atomic number 40. The name of zirconium is taken from the mineral zircon. Its atomic mass is 91.224. It is a lustrous, grey-white, strong transition metal that resembles titanium...

. Hidden named these occurrences "stars" and eagerly sought for them, as positive "pointers" to ore. At one point he noted a redness of skin and burning sensation when mining these, that he attributed to radioactivity, which was poorly understood at the time.(Hidden)

Mineral specimens from Baringer Hill eventually found their way into collections across the country, including the Houston Museum of Natural Science

Houston Museum of Natural Science

The Houston Museum of Natural Science is a science museum located on the northern border of Hermann Park in Houston, Texas, USA. The museum was established in 1909 by the Houston Museum and Scientific Society, an organization whose goals were to provide a free institution for the people of Houston...

, the American Museum of Natural History

American Museum of Natural History

The American Museum of Natural History , located on the Upper West Side of Manhattan in New York City, United States, is one of the largest and most celebrated museums in the world...

in New York, Harvard University

Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League university located in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States, established in 1636 by the Massachusetts legislature. Harvard is the oldest institution of higher learning in the United States and the first corporation chartered in the country...

, and the University of Texas at Austin

University of Texas at Austin

The University of Texas at Austin is a state research university located in Austin, Texas, USA, and is the flagship institution of the The University of Texas System. Founded in 1883, its campus is located approximately from the Texas State Capitol in Austin...

.

In Music

The song, "Ragged Wood" by the band Fleet FoxesFleet Foxes

Fleet Foxes are a folk rock band which formed in Seattle, Washington. They are signed to the Sub Pop and Bella Union record labels. The band came to prominence in 2008 with the release of their second EP, Sun Giant, and their debut full length album Fleet Foxes...

, references the site with the lyrics saying, "Lie to me if you will/at the top of Barringer Hill".