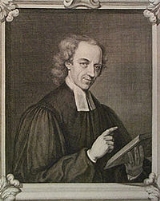

William Whiston

Encyclopedia

William Whiston was an English

theologian, historian

, and mathematician

. He is probably best known for his translation of the Antiquities of the Jews

and other works by Josephus

, his A New Theory of the Earth

, and his Arianism

. He succeeded his mentor Isaac Newton

as Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at the University of Cambridge

.

, in Leicestershire

, of which village his father was rector

. He was educated privately, partly on account of the delicacy of his health, and partly that he might act as amanuensis

to his father, who had lost his sight

. He studied at Queen Elizabeth Grammar School

, Tamworth

. After his father's death, he entered at Clare College, Cambridge

as a sizar

on June 30, 1686, where he applied himself to mathematical study, where he was awarded the degree of Bachelor of Arts (B.A.

) (1690), and A.M.

(1693), and was elected Fellow in 1691 and probationary senior Fellow in 1693. William Lloyd

ordained Whiston at Lichfield

in 1693. In 1694, claiming ill health, he resigned his tutorship at Clare to Richard Laughton, chaplain to John Moore (1646–1714), the bishop of Norwich

, and swapped positions with him. He now divided his time between Norwich, Cambridge and London. In 1698 Bishop More awarded him the living of Lowestoft

where he became Rector. In 1699 he resigned his Fellowship of Clare College and left in order to marry Ruth, daughter of George Antrobus, Whiston's headmaster at Tamworth school.

His A New Theory of the Earth from its Original to the Consummation of All Things

(1696), an articulation of creationism

and flood geology

which held that the global flood of Noah

had been caused by a comet

, obtained the praise of both Newton

and Locke

, the latter of whom classed the author among those who, if not adding much to our knowledge, "At least bring some new things to our thoughts." He was an early advocate, along with Edmond Halley

, of the periodicity of comets; he also held that comets were responsible for past catastrophes

in earth's history. In 1701 he resigned his Rectorship to become Isaac Newton's substitute as Lucasian lecturer at Cambridge, whom he succeeded in 1702. Here he engaged in joint research with his junior colleague Roger Cotes

, appointed with Whiston's patronage to the Plumian professorship in 1706.

In 1707 he was Boyle lecturer. For several years Whiston continued to write and preach both on mathematical and theological subjects with considerable success; but his study of the Apostolic Constitutions

In 1707 he was Boyle lecturer. For several years Whiston continued to write and preach both on mathematical and theological subjects with considerable success; but his study of the Apostolic Constitutions

had convinced him that Arianism

was the creed of the early church. For Whiston, to form an opinion and to publish it were things almost simultaneous. His heterodoxy

soon became notorious, and in 1710 he was deprived of his professor

ship and expelled from the university after a well-publicized hearing. The rest of his life was spent in incessant controversy — theological

, mathematical, chronological

, and miscellaneous. Because of his Arianism, Whiston was never invited to be a member of the Royal Society

, due probably to Newton's feelings about him after he published his unorthodox views. Whiston was permitted, however, to lecture to the Society frequently.

He vindicated his estimate of the Apostolical Constitutions and the Arian views he had derived from them in his Primitive Christianity Revived (5 vols., 1711–1712). In 1713 he produced a reformed liturgy

, and soon afterwards founded a society for promoting primitive Christianity, lecturing in support of his theories in halls and coffee-houses at London

, Bath, and Royal Tunbridge Wells

. In 1714, Whiston was instrumental in the establishment of the Board of Longitude

and for the next forty years made persevering efforts to solve the longitude problem

. He gave courses of demonstration lectures on astronomical and physical phenomena and engaged in many religious controversies. Whiston produced one of the first isoclinic maps of southern England in 1719 and 1721. One of the most valuable of his books, the Life of Samuel Clarke

, appeared in 1730.

While considered heretical

on many points, he was a firm believer in supernatural Christianity

, and frequently took the field in defense of prophecy

and miracle

, including anointing the sick and touching for the king's evil. His dislike of rationalism

in religion also made him one of the numerous opponents of Benjamin Hoadly

's Plain Account of the Nature and End of the Sacrament. He held that Song of Solomon

was apocrypha

l and that the Book of Baruch

was not. He was fervent in his views of ecclesiastical government and discipline, derived from the Apostolical Constitutions, on the ecclesiastical authorities. He challenged the teachings of Athanasius. He challenged Sir Isaac Newton's Biblical chronological system with success; but he himself lost not only time but money in an endeavour to solve the problem of longitude

. In 1736 he caused widespread anxiety among London's citizens when he predicted the world would end on October 16 of that year because a comet

would hit the earth; the Archbishop of Canterbury

, William Wake

, had to officially deny this prediction to ease the public.

Of all his singular opinions the best known is his advocacy of clerical monogamy

, immortalized in The Vicar of Wakefield

. Of all his labours the most useful is his translation of the works of Josephus

(1737), with notes and dissertations, still often reprinted to the present day. His last "famous discovery, or rather revival of Dr Giles Fletcher, the Elder

's," which he mentions in his autobiography with infinite complacency, was the identification of the Tatars

with the lost tribes of Israel. In 1745 he published his Primitive New Testament (on the basis of Codex Bezae

and Codex Claromontanus

). About the same time (1747) he finally left the Anglican communion

for the Baptist

, leaving the church literally as well as figuratively by quitting it as the clergyman began to read the Athanasian Creed

. He had a happy family life and died in Lyndon

Hall, Rutland

, at the home of his son-in-law, Samuel Barker

, on 22 August 1752. He was survived by his children Sarah, William, George, and John. Whiston left a memoir (3 vols., 1749–1750) which deserves more attention than it has received, both for its characteristic individuality and as a storehouse of curious anecdotes and illustrations of the religious and moral tendencies of the age. It does not, however, contain any account of the proceedings taken against him at Cambridge for his antitrinitarianism, these having been published separately at the time.

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

theologian, historian

Historian

A historian is a person who studies and writes about the past and is regarded as an authority on it. Historians are concerned with the continuous, methodical narrative and research of past events as relating to the human race; as well as the study of all history in time. If the individual is...

, and mathematician

Mathematician

A mathematician is a person whose primary area of study is the field of mathematics. Mathematicians are concerned with quantity, structure, space, and change....

. He is probably best known for his translation of the Antiquities of the Jews

Antiquities of the Jews

Antiquities of the Jews is a twenty volume historiographical work composed by the Jewish historian Flavius Josephus in the thirteenth year of the reign of Roman emperor Flavius Domitian which was around 93 or 94 AD. Antiquities of the Jews contains an account of history of the Jewish people,...

and other works by Josephus

Josephus

Titus Flavius Josephus , also called Joseph ben Matityahu , was a 1st-century Romano-Jewish historian and hagiographer of priestly and royal ancestry who recorded Jewish history, with special emphasis on the 1st century AD and the First Jewish–Roman War, which resulted in the Destruction of...

, his A New Theory of the Earth

A New Theory of the Earth

A New Theory of the Earth was a book written by William Whiston, in which he presented a description of the divine creation of the Earth and a posited global flood. He also postulated that the earth originated from the atmosphere of a comet and that all major changes in earth's history could be...

, and his Arianism

Arianism

Arianism is the theological teaching attributed to Arius , a Christian presbyter from Alexandria, Egypt, concerning the relationship of the entities of the Trinity and the precise nature of the Son of God as being a subordinate entity to God the Father...

. He succeeded his mentor Isaac Newton

Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton PRS was an English physicist, mathematician, astronomer, natural philosopher, alchemist, and theologian, who has been "considered by many to be the greatest and most influential scientist who ever lived."...

as Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at the University of Cambridge

University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a public research university located in Cambridge, United Kingdom. It is the second-oldest university in both the United Kingdom and the English-speaking world , and the seventh-oldest globally...

.

Early life and career

Whiston was born to Josiah Whiston and Katherine Rosse at Norton-juxta-TwycrossTwycross

Twycross is a small village and civil parish in Leicestershire, England on the A444 road. Parts of it are called Norton juxta — Latin for 'next to' — Twycross or Little Twycross...

, in Leicestershire

Leicestershire

Leicestershire is a landlocked county in the English Midlands. It takes its name from the heavily populated City of Leicester, traditionally its administrative centre, although the City of Leicester unitary authority is today administered separately from the rest of Leicestershire...

, of which village his father was rector

Rector

The word rector has a number of different meanings; it is widely used to refer to an academic, religious or political administrator...

. He was educated privately, partly on account of the delicacy of his health, and partly that he might act as amanuensis

Amanuensis

Amanuensis is a Latin word adopted in various languages, including English, for certain persons performing a function by hand, either writing down the words of another or performing manual labour...

to his father, who had lost his sight

Blindness

Blindness is the condition of lacking visual perception due to physiological or neurological factors.Various scales have been developed to describe the extent of vision loss and define blindness...

. He studied at Queen Elizabeth Grammar School

Queen Elizabeth's Mercian School

I go to this school and when I joined it was not a very good school and the more popular school was the nearby Rawlett but now it has turned into an academy it has a higher standard of education and better behaviour. So I am really pleased. So keep going Qems...

, Tamworth

Tamworth

Tamworth is a town and local government district in Staffordshire, England, located north-east of Birmingham city centre and north-west of London. The town takes its name from the River Tame, which flows through the town, as does the River Anker...

. After his father's death, he entered at Clare College, Cambridge

Clare College, Cambridge

Clare College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge in Cambridge, England.The college was founded in 1326, making it the second-oldest surviving college of the University after Peterhouse. Clare is famous for its chapel choir and for its gardens on "the Backs"...

as a sizar

Sizar

At Trinity College, Dublin and the University of Cambridge, a sizar is a student who receives some form of assistance such as meals, lower fees or lodging during his or her period of study, in some cases in return for doing a defined job....

on June 30, 1686, where he applied himself to mathematical study, where he was awarded the degree of Bachelor of Arts (B.A.

Bachelor of Arts

A Bachelor of Arts , from the Latin artium baccalaureus, is a bachelor's degree awarded for an undergraduate course or program in either the liberal arts, the sciences, or both...

) (1690), and A.M.

Master of Arts (postgraduate)

A Master of Arts from the Latin Magister Artium, is a type of Master's degree awarded by universities in many countries. The M.A. is usually contrasted with the M.S. or M.Sc. degrees...

(1693), and was elected Fellow in 1691 and probationary senior Fellow in 1693. William Lloyd

William Lloyd

William Lloyd may refer to:*William Watkiss Lloyd , writer*William Lloyd , Conservative councillor*William Lloyd , Bishop of St Asaph, of Lichfield and Coventry and of Worcester...

ordained Whiston at Lichfield

Lichfield

Lichfield is a cathedral city, civil parish and district in Staffordshire, England. One of eight civil parishes with city status in England, Lichfield is situated roughly north of Birmingham...

in 1693. In 1694, claiming ill health, he resigned his tutorship at Clare to Richard Laughton, chaplain to John Moore (1646–1714), the bishop of Norwich

Bishop of Norwich

The Bishop of Norwich is the Ordinary of the Church of England Diocese of Norwich in the Province of Canterbury.The diocese covers most of the County of Norfolk and part of Suffolk. The see is in the City of Norwich where the seat is located at the Cathedral Church of the Holy and Undivided...

, and swapped positions with him. He now divided his time between Norwich, Cambridge and London. In 1698 Bishop More awarded him the living of Lowestoft

Lowestoft

Lowestoft is a town in the English county of Suffolk. The town is on the North Sea coast and is the most easterly point of the United Kingdom. It is north-east of London, north-east of Ipswich and south-east of Norwich...

where he became Rector. In 1699 he resigned his Fellowship of Clare College and left in order to marry Ruth, daughter of George Antrobus, Whiston's headmaster at Tamworth school.

His A New Theory of the Earth from its Original to the Consummation of All Things

A New Theory of the Earth

A New Theory of the Earth was a book written by William Whiston, in which he presented a description of the divine creation of the Earth and a posited global flood. He also postulated that the earth originated from the atmosphere of a comet and that all major changes in earth's history could be...

(1696), an articulation of creationism

Creationism

Creationism is the religious beliefthat humanity, life, the Earth, and the universe are the creation of a supernatural being, most often referring to the Abrahamic god. As science developed from the 18th century onwards, various views developed which aimed to reconcile science with the Genesis...

and flood geology

Flood geology

Flood geology is the interpretation of the geological history of the Earth in terms of the global flood described in Genesis 6–9. Similar views played a part in the early development of the science of geology, even after the Biblical chronology had been rejected by geologists in favour of an...

which held that the global flood of Noah

Noah

Noah was, according to the Hebrew Bible, the tenth and last of the antediluvian Patriarchs. The biblical story of Noah is contained in chapters 6–9 of the book of Genesis, where he saves his family and representatives of all animals from the flood by constructing an ark...

had been caused by a comet

Comet

A comet is an icy small Solar System body that, when close enough to the Sun, displays a visible coma and sometimes also a tail. These phenomena are both due to the effects of solar radiation and the solar wind upon the nucleus of the comet...

, obtained the praise of both Newton

Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton PRS was an English physicist, mathematician, astronomer, natural philosopher, alchemist, and theologian, who has been "considered by many to be the greatest and most influential scientist who ever lived."...

and Locke

John Locke

John Locke FRS , widely known as the Father of Liberalism, was an English philosopher and physician regarded as one of the most influential of Enlightenment thinkers. Considered one of the first of the British empiricists, following the tradition of Francis Bacon, he is equally important to social...

, the latter of whom classed the author among those who, if not adding much to our knowledge, "At least bring some new things to our thoughts." He was an early advocate, along with Edmond Halley

Edmond Halley

Edmond Halley FRS was an English astronomer, geophysicist, mathematician, meteorologist, and physicist who is best known for computing the orbit of the eponymous Halley's Comet. He was the second Astronomer Royal in Britain, following in the footsteps of John Flamsteed.-Biography and career:Halley...

, of the periodicity of comets; he also held that comets were responsible for past catastrophes

Catastrophism

Catastrophism is the theory that the Earth has been affected in the past by sudden, short-lived, violent events, possibly worldwide in scope. The dominant paradigm of modern geology is uniformitarianism , in which slow incremental changes, such as erosion, create the Earth's appearance...

in earth's history. In 1701 he resigned his Rectorship to become Isaac Newton's substitute as Lucasian lecturer at Cambridge, whom he succeeded in 1702. Here he engaged in joint research with his junior colleague Roger Cotes

Roger Cotes

Roger Cotes FRS was an English mathematician, known for working closely with Isaac Newton by proofreading the second edition of his famous book, the Principia, before publication. He also invented the quadrature formulas known as Newton–Cotes formulas and first introduced what is known today as...

, appointed with Whiston's patronage to the Plumian professorship in 1706.

Arianism and later career

Apostolic Constitutions

The Apostolic Constitutions is a Christian collection of eight treatises which belongs to genre of the Church Orders. The work can be dated from 375 to 380 AD. The provenience is usually regarded as Syria, probably Antioch...

had convinced him that Arianism

Arianism

Arianism is the theological teaching attributed to Arius , a Christian presbyter from Alexandria, Egypt, concerning the relationship of the entities of the Trinity and the precise nature of the Son of God as being a subordinate entity to God the Father...

was the creed of the early church. For Whiston, to form an opinion and to publish it were things almost simultaneous. His heterodoxy

Heterodoxy

Heterodoxy is generally defined as "any opinions or doctrines at variance with an official or orthodox position". As an adjective, heterodox is commonly used to describe a subject as "characterized by departure from accepted beliefs or standards"...

soon became notorious, and in 1710 he was deprived of his professor

Professor

A professor is a scholarly teacher; the precise meaning of the term varies by country. Literally, professor derives from Latin as a "person who professes" being usually an expert in arts or sciences; a teacher of high rank...

ship and expelled from the university after a well-publicized hearing. The rest of his life was spent in incessant controversy — theological

Theology

Theology is the systematic and rational study of religion and its influences and of the nature of religious truths, or the learned profession acquired by completing specialized training in religious studies, usually at a university or school of divinity or seminary.-Definition:Augustine of Hippo...

, mathematical, chronological

Chronology

Chronology is the science of arranging events in their order of occurrence in time, such as the use of a timeline or sequence of events. It is also "the determination of the actual temporal sequence of past events".Chronology is part of periodization...

, and miscellaneous. Because of his Arianism, Whiston was never invited to be a member of the Royal Society

Royal Society

The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, known simply as the Royal Society, is a learned society for science, and is possibly the oldest such society in existence. Founded in November 1660, it was granted a Royal Charter by King Charles II as the "Royal Society of London"...

, due probably to Newton's feelings about him after he published his unorthodox views. Whiston was permitted, however, to lecture to the Society frequently.

He vindicated his estimate of the Apostolical Constitutions and the Arian views he had derived from them in his Primitive Christianity Revived (5 vols., 1711–1712). In 1713 he produced a reformed liturgy

Liturgy

Liturgy is either the customary public worship done by a specific religious group, according to its particular traditions or a more precise term that distinguishes between those religious groups who believe their ritual requires the "people" to do the "work" of responding to the priest, and those...

, and soon afterwards founded a society for promoting primitive Christianity, lecturing in support of his theories in halls and coffee-houses at London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

, Bath, and Royal Tunbridge Wells

Royal Tunbridge Wells

Royal Tunbridge Wells is a town in west Kent, England, about south-east of central London by road, by rail. The town is close to the border of the county of East Sussex...

. In 1714, Whiston was instrumental in the establishment of the Board of Longitude

Board of Longitude

The Board of Longitude was the popular name for the Commissioners for the Discovery of the Longitude at Sea. It was a British Government body formed in 1714 to administer a scheme of prizes intended to encourage innovators to solve the problem of finding longitude at sea.-Origins:Navigators and...

and for the next forty years made persevering efforts to solve the longitude problem

Longitude prize

The Longitude Prize was a reward offered by the British government for a simple and practical method for the precise determination of a ship's longitude...

. He gave courses of demonstration lectures on astronomical and physical phenomena and engaged in many religious controversies. Whiston produced one of the first isoclinic maps of southern England in 1719 and 1721. One of the most valuable of his books, the Life of Samuel Clarke

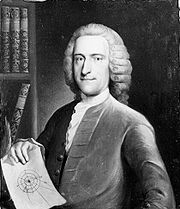

Samuel Clarke

thumb|right|200px|Samuel ClarkeSamuel Clarke was an English philosopher and Anglican clergyman.-Early life and studies:...

, appeared in 1730.

While considered heretical

Heresy

Heresy is a controversial or novel change to a system of beliefs, especially a religion, that conflicts with established dogma. It is distinct from apostasy, which is the formal denunciation of one's religion, principles or cause, and blasphemy, which is irreverence toward religion...

on many points, he was a firm believer in supernatural Christianity

Christianity

Christianity is a monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus as presented in canonical gospels and other New Testament writings...

, and frequently took the field in defense of prophecy

Prophecy

Prophecy is a process in which one or more messages that have been communicated to a prophet are then communicated to others. Such messages typically involve divine inspiration, interpretation, or revelation of conditioned events to come as well as testimonies or repeated revelations that the...

and miracle

Miracle

A miracle often denotes an event attributed to divine intervention. Alternatively, it may be an event attributed to a miracle worker, saint, or religious leader. A miracle is sometimes thought of as a perceptible interruption of the laws of nature. Others suggest that a god may work with the laws...

, including anointing the sick and touching for the king's evil. His dislike of rationalism

Rationalism

In epistemology and in its modern sense, rationalism is "any view appealing to reason as a source of knowledge or justification" . In more technical terms, it is a method or a theory "in which the criterion of the truth is not sensory but intellectual and deductive"...

in religion also made him one of the numerous opponents of Benjamin Hoadly

Benjamin Hoadly

Benjamin Hoadly was an English clergyman, who was successively Bishop of Bangor, Hereford, Salisbury, and Winchester. He is best known as the initiator of the Bangorian Controversy.-Life:...

's Plain Account of the Nature and End of the Sacrament. He held that Song of Solomon

Song of Solomon

The Song of Songs of Solomon, commonly referred to as Song of Songs or Song of Solomon, is a book of the Hebrew Bible—one of the megillot —found in the last section of the Tanakh, known as the Ketuvim...

was apocrypha

Apocrypha

The term apocrypha is used with various meanings, including "hidden", "esoteric", "spurious", "of questionable authenticity", ancient Chinese "revealed texts and objects" and "Christian texts that are not canonical"....

l and that the Book of Baruch

Book of Baruch

The Book of Baruch, occasionally referred to as 1 Baruch, is called a deuterocanonical book of the Bible. Although not in the Hebrew Bible, it is found in the Septuagint and in the Vulgate Bible, and also in Theodotion's version. It is grouped with the prophetical books which also include Isaiah,...

was not. He was fervent in his views of ecclesiastical government and discipline, derived from the Apostolical Constitutions, on the ecclesiastical authorities. He challenged the teachings of Athanasius. He challenged Sir Isaac Newton's Biblical chronological system with success; but he himself lost not only time but money in an endeavour to solve the problem of longitude

Longitude

Longitude is a geographic coordinate that specifies the east-west position of a point on the Earth's surface. It is an angular measurement, usually expressed in degrees, minutes and seconds, and denoted by the Greek letter lambda ....

. In 1736 he caused widespread anxiety among London's citizens when he predicted the world would end on October 16 of that year because a comet

Comet

A comet is an icy small Solar System body that, when close enough to the Sun, displays a visible coma and sometimes also a tail. These phenomena are both due to the effects of solar radiation and the solar wind upon the nucleus of the comet...

would hit the earth; the Archbishop of Canterbury

Archbishop of Canterbury

The Archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and principal leader of the Church of England, the symbolic head of the worldwide Anglican Communion, and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. In his role as head of the Anglican Communion, the archbishop leads the third largest group...

, William Wake

William Wake

William Wake was a priest in the Church of England and Archbishop of Canterbury from 1716 until his death in 1737.-Life:...

, had to officially deny this prediction to ease the public.

Of all his singular opinions the best known is his advocacy of clerical monogamy

Monogamy

Monogamy /Gr. μονός+γάμος - one+marriage/ a form of marriage in which an individual has only one spouse at any one time. In current usage monogamy often refers to having one sexual partner irrespective of marriage or reproduction...

, immortalized in The Vicar of Wakefield

The Vicar of Wakefield

The Vicar of Wakefield is a novel by Irish author Oliver Goldsmith. It was written in 1761 and 1762, and published in 1766, and was one of the most popular and widely read 18th-century novels among Victorians...

. Of all his labours the most useful is his translation of the works of Josephus

Josephus

Titus Flavius Josephus , also called Joseph ben Matityahu , was a 1st-century Romano-Jewish historian and hagiographer of priestly and royal ancestry who recorded Jewish history, with special emphasis on the 1st century AD and the First Jewish–Roman War, which resulted in the Destruction of...

(1737), with notes and dissertations, still often reprinted to the present day. His last "famous discovery, or rather revival of Dr Giles Fletcher, the Elder

Giles Fletcher, the Elder

Giles Fletcher, the Elder was an English poet and diplomat, member of the English Parliament.Giles Fletcher was the son of Richard Fletcher, vicar of Bishop's Stortford. He spent his early life at Cranbrook before entering Eton College about 1561...

's," which he mentions in his autobiography with infinite complacency, was the identification of the Tatars

Tatars

Tatars are a Turkic speaking ethnic group , numbering roughly 7 million.The majority of Tatars live in the Russian Federation, with a population of around 5.5 million, about 2 million of which in the republic of Tatarstan.Significant minority populations are found in Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan,...

with the lost tribes of Israel. In 1745 he published his Primitive New Testament (on the basis of Codex Bezae

Codex Bezae

The Codex Bezae Cantabrigensis, designated by siglum Dea or 05 , δ 5 , is a codex of the New Testament dating from the 5th century written in an uncial hand on vellum. It contains, in both Greek and Latin, most of the four Gospels and Acts, with a small fragment of the 3 John...

and Codex Claromontanus

Codex Claromontanus

Codex Claromontanus, symbolized by Dp or 06 , δ 1026 , is a Greek-Latin diglot uncial manuscript of the New Testament, written in an uncial hand on vellum. The Greek and Latin text on facing pages...

). About the same time (1747) he finally left the Anglican communion

Anglican Communion

The Anglican Communion is an international association of national and regional Anglican churches in full communion with the Church of England and specifically with its principal primate, the Archbishop of Canterbury...

for the Baptist

Baptist

Baptists comprise a group of Christian denominations and churches that subscribe to a doctrine that baptism should be performed only for professing believers , and that it must be done by immersion...

, leaving the church literally as well as figuratively by quitting it as the clergyman began to read the Athanasian Creed

Athanasian Creed

The Athanasian Creed is a Christian statement of belief, focusing on Trinitarian doctrine and Christology. The Latin name of the creed, Quicumque vult, is taken from the opening words, "Whosoever wishes." The Athanasian Creed has been used by Christian churches since the sixth century...

. He had a happy family life and died in Lyndon

Lyndon, Rutland

Lyndon is a small village in the county of Rutland in the East Midlands of England.Thomas Barker of Lyndon Hall kept a detailed weather record from 1736 to 1798. William Whiston , best known for his translation of Josephus, died at the Hall, the home of his son-in-law, Samuel Barker on 22 August...

Hall, Rutland

Rutland

Rutland is a landlocked county in central England, bounded on the west and north by Leicestershire, northeast by Lincolnshire and southeast by Peterborough and Northamptonshire....

, at the home of his son-in-law, Samuel Barker

Samuel Barker (Hebraist)

-Life:Barker was the son of Augustin Barker of South Luffenham and Thomasyn Tryst of Maidford, Northants, and inherited the Lordship of the Manor of Lyndon, Rutland by the bequest of his father's second cousin Sir Thomas Barker, 2nd Bt of Lyndon . Sir Thomas was a member of the 'Order of Little...

, on 22 August 1752. He was survived by his children Sarah, William, George, and John. Whiston left a memoir (3 vols., 1749–1750) which deserves more attention than it has received, both for its characteristic individuality and as a storehouse of curious anecdotes and illustrations of the religious and moral tendencies of the age. It does not, however, contain any account of the proceedings taken against him at Cambridge for his antitrinitarianism, these having been published separately at the time.

See also

- A New Theory of the EarthA New Theory of the EarthA New Theory of the Earth was a book written by William Whiston, in which he presented a description of the divine creation of the Earth and a posited global flood. He also postulated that the earth originated from the atmosphere of a comet and that all major changes in earth's history could be...

- Lucasian Professor

- ArianismArianismArianism is the theological teaching attributed to Arius , a Christian presbyter from Alexandria, Egypt, concerning the relationship of the entities of the Trinity and the precise nature of the Son of God as being a subordinate entity to God the Father...

- Isaac NewtonIsaac NewtonSir Isaac Newton PRS was an English physicist, mathematician, astronomer, natural philosopher, alchemist, and theologian, who has been "considered by many to be the greatest and most influential scientist who ever lived."...

- Noah's Flood

- CatastrophismCatastrophismCatastrophism is the theory that the Earth has been affected in the past by sudden, short-lived, violent events, possibly worldwide in scope. The dominant paradigm of modern geology is uniformitarianism , in which slow incremental changes, such as erosion, create the Earth's appearance...

- Biblical prophecy

- Dorsa WhistonDorsa WhistonDorsa Whiston is a wrinkle ridge system at in Oceanus Procellarum on the Moon. It is 85 km long and was named after William Whiston in 1976....

, named after him

External links

- Biography of William Whiston at the LucasianChair.org, the homepage of the Lucasian Chair of Mathematics at Cambridge University

- Bibliography for William Whiston at the LucasianChair.org the homepage of the Lucasian Chair of Mathematics at Cambridge University

- Whiston's MacTutor Biography

- Works and translations by Whiston, in the Internet ArchiveInternet ArchiveThe Internet Archive is a non-profit digital library with the stated mission of "universal access to all knowledge". It offers permanent storage and access to collections of digitized materials, including websites, music, moving images, and nearly 3 million public domain books. The Internet Archive...

- "Account of Newton", Collection of Authentick Records (1728), pp. 1070–1082

- "The Works of Flavius Josephus" translated by William Whiston

- "William Whiston and the Deluge" by Immanuel VelikovskyImmanuel VelikovskyImmanuel Velikovsky was a Russian-born American independent scholar of Jewish origins, best known as the author of a number of controversial books reinterpreting the events of ancient history, in particular the US bestseller Worlds in Collision, published in 1950...

- "Whiston's Flood"

- Whiston biography at Chambers' Book of Days

- Whiston biography at NNDB

- Some of Whiston's views on biblical prophecy

- "William Whiston, The Universal Deluge, and a Terrible Specracle" by Roomet Jakapi

- Collection of Authentick Records by Whiston at the Newton Project

- William Whiston, 1667-1752

- Collection of William Whiston portraits at England's National Portrait GalleryNational Portrait Gallery (England)The National Portrait Gallery is an art gallery in London, England, housing a collection of portraits of historically important and famous British people. It was the first portrait gallery in the world when it opened in 1856. The gallery moved in 1896 to its current site at St Martin's Place, off...

- Primitive New Testament