Theories and sociology of the history of science

Encyclopedia

The sociology and philosophy of science

, as well as the entire field of science studies

, have in the 20th century been occupied with the question of large-scale patterns and trends in the development of science

, and asking questions about how science "works" both in a philosophical and practical sense.

Available methods of communication have improved tremendously over time. Instead of waiting months or years for a hand-copied letter to arrive, today scientific communication can be practically instantaneous. Earlier, most natural philosophers worked in relative isolation, due to the difficulty and slowness of communication. Still, there was a considerable amount of cross-fertilization between distant groups and individuals.

Nowadays, almost all modern scientists participate in a scientific community

, hypothetically global in nature (though often based around a relatively few number of nations and institutions of stature), but also strongly segregated into different fields of study. The scientific community is important because it represents a source of established knowledge which, if used properly, ought to be more reliable than personally acquired knowledge of any given individual. The community also provides a feedback

mechanism, often in the form of practices such as peer review

and reproducibility

. Most items of scientific content (experimental results, theoretical proposals, or literature reviews) are reported in scientific journal

s and are hypothetically subjected to the scrutiny of their peers, though a number of scholarly critics from both inside and outside the scientific community have, in recent decades, began to question the effect of commercial and government investment in science on the peer review and publishing process, as well as the internal disciplinary limitations to the scientific publication process.

A major development of the Scientific Revolution

was the foundation of scientific societies: Academia Secretorum Naturae

(Accademia dei Segreti, the Academy of the Mysteries of Nature) can be considered the first scientific community; founded in Naples

1560 by Giambattista della Porta

. The Academy had an exclusive membership rule: discovery of a new law of nature was a prequisite for admission. It was soon shut down by Pope Paul V

under suspicion of sorcery

.

The Academia Secretorum Naturae was replaced by the Accademia dei Lincei

, which was founded in Rome

1603. The Lincei included Galileo as a member, but failed upon his condemnation in 1633. The Accademia del Cimento

, Florence

1657, lasted 10 years. The Royal Society

of London, 1660 to the present day, brought together a diverse collection of scientists to discuss theories, conduct experiments, and review each other's work. The Académie des Sciences was created as an institution of the government of France 1666, meeting in the King's library. The Akademie der Wissenschaften began in Berlin

1700.

Early scientific societies provided valuable functions, including a community open to and interested in empirical inquiry, and also more familiar with and more educated about the subject. In 1758, with the aid of his pupils, Lagrange

established a society, which was subsequently incorporated as the Turin Academy.

Much of what is considered the modern institution of science was formed during its professionalization in the 19th century. During this time the location of scientific research shifted primarily to universities

, though also to some extent it also became a standard component of industry

as well. In the early years of the 20th century, especially after the role of science in the first World War

, governments of major industrial nations began to invest heavily in scientific research. This effort was dwarfed by the funding of scientific research undertaken by all sides in World War II

, which produced such "wonder weapons" as radar

, rocket

ry, and the atomic bomb. During the Cold War

, a large amount of government resources were poured into science by the USA, USSR, and many European powers. It was during this time that DARPA funded nationwide computer networks of networks, one of them eventually under the internet protocol

. In the post-Cold War era, a decline in government funding from many countries has been met with an increase of industrial and private investment. The funding of science is a major factor in its historical and global development, as though science is hypothetically international in scope, in a practical sense it has usually centered around wherever it could find the most funding.

operates under the aegis of the monarchy; in the US, the National Academy of Sciences

was founded by Act of the United States Congress

; etc. Otherwise, when the basic elements of knowledge were being formulated, the political rulers of the respective communities could choose to arbitrarily either support or disallow the nascent scientific communities. For example, Alhazen had to feign madness to avoid execution. The polymath Shen Kuo

lost political support, and could not continue his studies until he came up with discoveries that showed his worth to the political rulers. The admiral Zheng He

could not continue his voyages of exploration after the emperors withdrew their support. Another famous example was the suppression of the work of Galileo, by the twentieth century, Galileo would be pardoned.

.

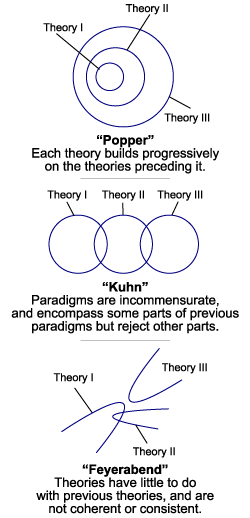

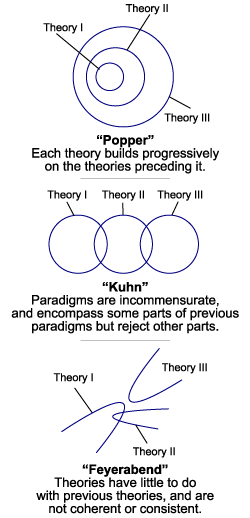

The first major model, implicit in most early histories of science and generally a model put forward by practicing scientists themselves in their textbook literature, is associated with the criticisms of logical positivism

The first major model, implicit in most early histories of science and generally a model put forward by practicing scientists themselves in their textbook literature, is associated with the criticisms of logical positivism

by Karl Popper

(1902–1994) from the 1930s. Popper's model of science is one in which scientific progress

is achieved through a falsification

of incorrect theories and the adoption instead of theories which are progressively closer to truth. In this model, scientific progress is a linear accumulation of facts, each one adding to the last. In this model, the physics

of Aristotle

(384 BC 322 BC) was simply subsumed by the work of Isaac Newton

(1642–1727) (classical mechanics

), which itself was eclipsed by the work of Albert Einstein

(1879–1955) (Relativity

), and later the theory of quantum mechanics

(established in 1925), each one more accurate than the last.

A major challenge to this model came from the work of the historian and philosopher Thomas Kuhn

(1922–1996) in his work The Structure of Scientific Revolutions

published in 1962. Kuhn, a former physicist, argued against the view that scientific progress was linear, and that modern scientific theories were necessarily just more accurate versions of theories of the past. Rather, Kuhn's version of scientific development consisted of dominant structures of thought and practices, which he called "paradigm

s", in which research went through phases of "normal

" science ("puzzle solving") and "revolutionary" science (testing out new theories based on new assumptions, brought on by uncertainty and crisis in existing theories). In Kuhn's model, different paradigms represented entirely different and incommensurate

assumptions about the universe, and was uncertain about whether paradigms shifted in a way which necessarily relied upon greater attainment of truth. In Kuhn's view, Aristotle's physics, Newton's classical mechanics, and Einstein's Relativity were entirely different ways to think about the world; each successive paradigm defined what questions could be asked about the world and (perhaps arbitrarily) discarded aspects of the previous paradigm which no longer seemed applicable or important. Kuhn claimed that far from merely building on the previous theory's accomplishments, each one essentially throws out the old way of looking at the universe, and comes up with its own vocabulary to describe it and its own guidelines for expanding knowledge within the new paradigm

.

Kuhn's model met with much suspicion from scientists, historians, and philosophers. Some scientists felt that Kuhn went too far in divorcing scientific progress from truth; many historians felt that his argument was too codified for something as polyvariant and historically contingent as scientific change; and many philosophers felt that the argument did not go far enough. The furthest extreme of such reasoning was put forth by the philosopher Paul Feyerabend

(1924–1994), who argued that there were no consistent methodologies used by all scientists at all times which allowed certain forms of inquiry to be labeled "scientific" in a way which made them different from any other form of inquiry, such as witchcraft

. Feyerabend argued harshly against the notion that falsification was ever truly followed in the history of science, and noted that scientists had long undertaken practices to arbitrarily consider theories to be accurate even if they failed many sets of tests. Feyerabend argued that a pluralistic methodology should be undertaken for the investigation of knowledge, and noted that many forms of knowledge which were previously thought to be "non-scientific" were later accepted as a valid part of scientific canon.

Many other theories of scientific change have been proposed over the years with various changes of emphasis and implications. In general, though, most float somewhere between these three models for change in scientific theory, the connection between theory and truth, and the nature of scientific progress.

are often celebrated as genius

es and hero

es of science. Popularizers of science, including the news media and scientific biographers, contribute to this phenomenon. But many scientific historians emphasize the collective aspects of scientific discovery, and de-emphasize the importance of the "Eureka!" moment

.

A detailed look at the history of science often reveals that the minds of great thinkers were primed with the results of previous efforts, and often arrive on the scene to find a crisis of one kind or another. For example, Einstein did not consider the physics of motion and gravitation in isolation. His major accomplishments solved a problem which had come to a head in the field only in recent years — empirical data showing that the speed of light was inexplicably constant, no matter the apparent speed of the observer. (See Michelson-Morley experiment

.) Without this information, it is very unlikely that Einstein would have conceived of anything like relativity.

The question of who should get credit for any given discovery is often a source of some controversy. There are many priority disputes, in which multiple individuals or teams have competing claims over who discovered something first. Multiple simultaneous discovery is actually a surprisingly common phenomenon, perhaps largely explained by the idea that previous contributions (including the emergence of contradictions between existing theories, or unexpected empirical results) make a certain concept ready for discovery. Simple priority disputes are often a matter of documenting when certain experiments were performed, or when certain ideas were first articulated to colleagues or recorded in a fixed medium.

Many times the question of exactly which event should qualify as the moment of discovery is difficult to answer. One of the most famous examples of this is the question of the discovery of oxygen

. While Carl Wilhelm Scheele

and Joseph Priestley

were able to concentrate oxygen, in the laboratory and characterize its properties, they did not recognize it as a component of air. Priestly actually thought it was missing a hypothetical component of air, known as phlogiston

, which air was supposed to absorb from materials that are being burned. It was only several years later that Antoine Lavoisier

first conceived of the modern notion of oxygen — as a substance that is consumed from the air in the processes of burning and respiration.

By the late 20th Century, scientific research has become a large-scale effort, largely accomplished in institutional teams. The amount and frequency of inter-team collaboration has continued to increase, especially after the rise of the Internet

, which is a central tool for the modern scientific community. This further complicates the notion of individual accomplishment in science.

Philosophy of science

The philosophy of science is concerned with the assumptions, foundations, methods and implications of science. It is also concerned with the use and merit of science and sometimes overlaps metaphysics and epistemology by exploring whether scientific results are actually a study of truth...

, as well as the entire field of science studies

Science studies

Science studies is an interdisciplinary research area that seeks to situate scientific expertise in a broad social, historical, and philosophical context. It is concerned with the history of academic disciplines, the interrelationships between science and society, and the alleged covert purposes...

, have in the 20th century been occupied with the question of large-scale patterns and trends in the development of science

Science

Science is a systematic enterprise that builds and organizes knowledge in the form of testable explanations and predictions about the universe...

, and asking questions about how science "works" both in a philosophical and practical sense.

Science as a social enterprise

Science as a social enterprise has been developing exponentially for the past few centuries. In antiquity, the few people who were able to engage in natural inquiry were either wealthy themselves, had rich benefactors, or had the support of a religious community. Today, scientific research has tremendous government support and also ongoing support from the private sector.Available methods of communication have improved tremendously over time. Instead of waiting months or years for a hand-copied letter to arrive, today scientific communication can be practically instantaneous. Earlier, most natural philosophers worked in relative isolation, due to the difficulty and slowness of communication. Still, there was a considerable amount of cross-fertilization between distant groups and individuals.

Nowadays, almost all modern scientists participate in a scientific community

Scientific community

The scientific community consists of the total body of scientists, its relationships and interactions. It is normally divided into "sub-communities" each working on a particular field within science. Objectivity is expected to be achieved by the scientific method...

, hypothetically global in nature (though often based around a relatively few number of nations and institutions of stature), but also strongly segregated into different fields of study. The scientific community is important because it represents a source of established knowledge which, if used properly, ought to be more reliable than personally acquired knowledge of any given individual. The community also provides a feedback

Feedback

Feedback describes the situation when output from an event or phenomenon in the past will influence an occurrence or occurrences of the same Feedback describes the situation when output from (or information about the result of) an event or phenomenon in the past will influence an occurrence or...

mechanism, often in the form of practices such as peer review

Peer review

Peer review is a process of self-regulation by a profession or a process of evaluation involving qualified individuals within the relevant field. Peer review methods are employed to maintain standards, improve performance and provide credibility...

and reproducibility

Reproducibility

Reproducibility is the ability of an experiment or study to be accurately reproduced, or replicated, by someone else working independently...

. Most items of scientific content (experimental results, theoretical proposals, or literature reviews) are reported in scientific journal

Scientific journal

In academic publishing, a scientific journal is a periodical publication intended to further the progress of science, usually by reporting new research. There are thousands of scientific journals in publication, and many more have been published at various points in the past...

s and are hypothetically subjected to the scrutiny of their peers, though a number of scholarly critics from both inside and outside the scientific community have, in recent decades, began to question the effect of commercial and government investment in science on the peer review and publishing process, as well as the internal disciplinary limitations to the scientific publication process.

A major development of the Scientific Revolution

Scientific revolution

The Scientific Revolution is an era associated primarily with the 16th and 17th centuries during which new ideas and knowledge in physics, astronomy, biology, medicine and chemistry transformed medieval and ancient views of nature and laid the foundations for modern science...

was the foundation of scientific societies: Academia Secretorum Naturae

Academia Secretorum Naturae

The first scientific society, the Academia Secretorum Naturae was founded in Naples in 1560 by Giambattista della Porta, a noted polymath. In Italian it was called Accademia dei Segreti, the Academy of the Mysteries of Nature, and the members referred to themselves as the otiosi...

(Accademia dei Segreti, the Academy of the Mysteries of Nature) can be considered the first scientific community; founded in Naples

Naples

Naples is a city in Southern Italy, situated on the country's west coast by the Gulf of Naples. Lying between two notable volcanic regions, Mount Vesuvius and the Phlegraean Fields, it is the capital of the region of Campania and of the province of Naples...

1560 by Giambattista della Porta

Giambattista della Porta

Giambattista della Porta , also known as Giovanni Battista Della Porta and John Baptist Porta, was an Italian scholar, polymath and playwright who lived in Naples at the time of the Scientific Revolution and Reformation....

. The Academy had an exclusive membership rule: discovery of a new law of nature was a prequisite for admission. It was soon shut down by Pope Paul V

Pope Paul V

-Theology:Paul met with Galileo Galilei in 1616 after Cardinal Bellarmine had, on his orders, warned Galileo not to hold or defend the heliocentric ideas of Copernicus. Whether there was also an order not to teach those ideas in any way has been a matter for controversy...

under suspicion of sorcery

Magic (paranormal)

Magic is the claimed art of manipulating aspects of reality either by supernatural means or through knowledge of occult laws unknown to science. It is in contrast to science, in that science does not accept anything not subject to either direct or indirect observation, and subject to logical...

.

The Academia Secretorum Naturae was replaced by the Accademia dei Lincei

Accademia dei Lincei

The Accademia dei Lincei, , is an Italian science academy, located at the Palazzo Corsini on the Via della Lungara in Rome, Italy....

, which was founded in Rome

Rome

Rome is the capital of Italy and the country's largest and most populated city and comune, with over 2.7 million residents in . The city is located in the central-western portion of the Italian Peninsula, on the Tiber River within the Lazio region of Italy.Rome's history spans two and a half...

1603. The Lincei included Galileo as a member, but failed upon his condemnation in 1633. The Accademia del Cimento

Accademia del Cimento

The Accademia del Cimento , an early scientific society, was founded in Florence 1657 by students of Galileo, Giovanni Alfonso Borelli and Vincenzo Viviani. The foundation of Academy was funded by Prince Leopoldo and Grand Duke Ferdinando II de' Medici...

, Florence

Florence

Florence is the capital city of the Italian region of Tuscany and of the province of Florence. It is the most populous city in Tuscany, with approximately 370,000 inhabitants, expanding to over 1.5 million in the metropolitan area....

1657, lasted 10 years. The Royal Society

Royal Society

The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, known simply as the Royal Society, is a learned society for science, and is possibly the oldest such society in existence. Founded in November 1660, it was granted a Royal Charter by King Charles II as the "Royal Society of London"...

of London, 1660 to the present day, brought together a diverse collection of scientists to discuss theories, conduct experiments, and review each other's work. The Académie des Sciences was created as an institution of the government of France 1666, meeting in the King's library. The Akademie der Wissenschaften began in Berlin

Berlin

Berlin is the capital city of Germany and is one of the 16 states of Germany. With a population of 3.45 million people, Berlin is Germany's largest city. It is the second most populous city proper and the seventh most populous urban area in the European Union...

1700.

Early scientific societies provided valuable functions, including a community open to and interested in empirical inquiry, and also more familiar with and more educated about the subject. In 1758, with the aid of his pupils, Lagrange

Joseph Louis Lagrange

Joseph-Louis Lagrange , born Giuseppe Lodovico Lagrangia, was a mathematician and astronomer, who was born in Turin, Piedmont, lived part of his life in Prussia and part in France, making significant contributions to all fields of analysis, to number theory, and to classical and celestial mechanics...

established a society, which was subsequently incorporated as the Turin Academy.

Much of what is considered the modern institution of science was formed during its professionalization in the 19th century. During this time the location of scientific research shifted primarily to universities

University

A university is an institution of higher education and research, which grants academic degrees in a variety of subjects. A university is an organisation that provides both undergraduate education and postgraduate education...

, though also to some extent it also became a standard component of industry

Industry

Industry refers to the production of an economic good or service within an economy.-Industrial sectors:There are four key industrial economic sectors: the primary sector, largely raw material extraction industries such as mining and farming; the secondary sector, involving refining, construction,...

as well. In the early years of the 20th century, especially after the role of science in the first World War

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

, governments of major industrial nations began to invest heavily in scientific research. This effort was dwarfed by the funding of scientific research undertaken by all sides in World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

, which produced such "wonder weapons" as radar

Radar

Radar is an object-detection system which uses radio waves to determine the range, altitude, direction, or speed of objects. It can be used to detect aircraft, ships, spacecraft, guided missiles, motor vehicles, weather formations, and terrain. The radar dish or antenna transmits pulses of radio...

, rocket

Rocket

A rocket is a missile, spacecraft, aircraft or other vehicle which obtains thrust from a rocket engine. In all rockets, the exhaust is formed entirely from propellants carried within the rocket before use. Rocket engines work by action and reaction...

ry, and the atomic bomb. During the Cold War

Cold War

The Cold War was the continuing state from roughly 1946 to 1991 of political conflict, military tension, proxy wars, and economic competition between the Communist World—primarily the Soviet Union and its satellite states and allies—and the powers of the Western world, primarily the United States...

, a large amount of government resources were poured into science by the USA, USSR, and many European powers. It was during this time that DARPA funded nationwide computer networks of networks, one of them eventually under the internet protocol

Internet Protocol

The Internet Protocol is the principal communications protocol used for relaying datagrams across an internetwork using the Internet Protocol Suite...

. In the post-Cold War era, a decline in government funding from many countries has been met with an increase of industrial and private investment. The funding of science is a major factor in its historical and global development, as though science is hypothetically international in scope, in a practical sense it has usually centered around wherever it could find the most funding.

Major events in the history of scientific communication

- The cave paintingCave paintingCave paintings are paintings on cave walls and ceilings, and the term is used especially for those dating to prehistoric times. The earliest European cave paintings date to the Aurignacian, some 32,000 years ago. The purpose of the paleolithic cave paintings is not known...

s depicted events, with no commentary. From 40,000 BC to 15,000 BC. - The Ishango BoneIshango boneThe Ishango bone is a bone tool, dated to the Upper Paleolithic era. It is a dark brown length of bone, the fibula of a baboon, with a sharp piece of quartz affixed to one end, perhaps for engraving...

dated 25,000 years ago could only show talliesTally marksTally marks, or hash marks, are a unary numeral system. They are a form of numeral used for counting. They allow updating written intermediate results without erasing or discarding anything written down...

in mathematical notationMathematical notationMathematical notation is a system of symbolic representations of mathematical objects and ideas. Mathematical notations are used in mathematics, the physical sciences, engineering, and economics...

. - The clay tablets of Mesopotamia show the scale of the commentary or the information: the argument and logic of a discovery would be limited to what fit on the tablet. From late 4th millennium4th millenniumThe fourth millennium is a period of time that will begin on January 1, 3001, and will end on December 31, 4000, of the Gregorian calendar.-Centuries and Decades:* 31st century–3000s 3010s 3020s 3030s 3040s 3050s 3060s 3070s 3080s 3090s...

onwards. - PoetryPoetryPoetry is a form of literary art in which language is used for its aesthetic and evocative qualities in addition to, or in lieu of, its apparent meaning...

and rhymeRhymeA rhyme is a repetition of similar sounds in two or more words and is most often used in poetry and songs. The word "rhyme" may also refer to a short poem, such as a rhyming couplet or other brief rhyming poem such as nursery rhymes.-Etymology:...

allowed people to remember memorable events more easily. For example, the ChineseChinaChinese civilization may refer to:* China for more general discussion of the country.* Chinese culture* Greater China, the transnational community of ethnic Chinese.* History of China* Sinosphere, the area historically affected by Chinese culture...

generation nameGeneration nameGeneration name, variously zibei or banci, is one of the characters in a traditional Chinese name, and is so called because each member of a generation share that character, unlike surnames or given names...

s are taken from a poem selected by each family. - The parchmentParchmentParchment is a thin material made from calfskin, sheepskin or goatskin, often split. Its most common use was as a material for writing on, for documents, notes, or the pages of a book, codex or manuscript. It is distinct from leather in that parchment is limed but not tanned; therefore, it is very...

and paperPaperPaper is a thin material mainly used for writing upon, printing upon, drawing or for packaging. It is produced by pressing together moist fibers, typically cellulose pulp derived from wood, rags or grasses, and drying them into flexible sheets....

scrollScrollA scroll is a roll of parchment, papyrus, or paper, which has been drawn or written upon.Scroll may also refer to:*Scroll , the decoratively curved end of the pegbox of string instruments such as violins...

s which arose in Greek and in Chinese culture could start to contain the history and development of ideas and discoveries. Parchment was invented in PergamonPergamonPergamon , or Pergamum, was an ancient Greek city in modern-day Turkey, in Mysia, today located from the Aegean Sea on a promontory on the north side of the river Caicus , that became the capital of the Kingdom of Pergamon during the Hellenistic period, under the Attalid dynasty, 281–133 BC...

in the 2nd century BC, while the maunfacture of paper was described for the first time in 105 AD in China. It was brought to Western world only in the 13th century. - The codexCodexA codex is a book in the format used for modern books, with multiple quires or gatherings typically bound together and given a cover.Developed by the Romans from wooden writing tablets, its gradual replacement...

or bookBookA book is a set or collection of written, printed, illustrated, or blank sheets, made of hot lava, paper, parchment, or other materials, usually fastened together to hinge at one side. A single sheet within a book is called a leaf or leaflet, and each side of a leaf is called a page...

of medieval times allowed random access to specific passages. The systematic printing and production of books could then allow the systematic production of new ideas. From late 1st century onwards. - By the 20th century, the scale and scope of scientific work allowed collaborationCollaborationCollaboration is working together to achieve a goal. It is a recursive process where two or more people or organizations work together to realize shared goals, — for example, an intriguing endeavor that is creative in nature—by sharing...

of researchers and the definition of consistent protocolCommunications protocolA communications protocol is a system of digital message formats and rules for exchanging those messages in or between computing systems and in telecommunications...

s for this collaboration in scientific work.

Political support

One of the basic requirements for a scientific community is the existence and approval of a political sponsor; in England, the Royal SocietyRoyal Society

The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, known simply as the Royal Society, is a learned society for science, and is possibly the oldest such society in existence. Founded in November 1660, it was granted a Royal Charter by King Charles II as the "Royal Society of London"...

operates under the aegis of the monarchy; in the US, the National Academy of Sciences

United States National Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences is a corporation in the United States whose members serve pro bono as "advisers to the nation on science, engineering, and medicine." As a national academy, new members of the organization are elected annually by current members, based on their distinguished and...

was founded by Act of the United States Congress

United States Congress

The United States Congress is the bicameral legislature of the federal government of the United States, consisting of the Senate and the House of Representatives. The Congress meets in the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C....

; etc. Otherwise, when the basic elements of knowledge were being formulated, the political rulers of the respective communities could choose to arbitrarily either support or disallow the nascent scientific communities. For example, Alhazen had to feign madness to avoid execution. The polymath Shen Kuo

Shen Kuo

Shen Kuo or Shen Gua , style name Cunzhong and pseudonym Mengqi Weng , was a polymathic Chinese scientist and statesman of the Song Dynasty...

lost political support, and could not continue his studies until he came up with discoveries that showed his worth to the political rulers. The admiral Zheng He

Zheng He

Zheng He , also known as Ma Sanbao and Hajji Mahmud Shamsuddin was a Hui-Chinese mariner, explorer, diplomat and fleet admiral, who commanded voyages to Southeast Asia, South Asia, the Middle East, and East Africa, collectively referred to as the Voyages of Zheng He or Voyages of Cheng Ho from...

could not continue his voyages of exploration after the emperors withdrew their support. Another famous example was the suppression of the work of Galileo, by the twentieth century, Galileo would be pardoned.

Patterns in the history of science

One of the major occupations with those interested in the history of science is whether or not it displays certain patterns or trends, usually along the question of change between one or more scientific theories. Generally speaking, there have historically been three major models adopted in various forms within the philosophy of sciencePhilosophy of science

The philosophy of science is concerned with the assumptions, foundations, methods and implications of science. It is also concerned with the use and merit of science and sometimes overlaps metaphysics and epistemology by exploring whether scientific results are actually a study of truth...

.

Logical positivism

Logical positivism is a philosophy that combines empiricism—the idea that observational evidence is indispensable for knowledge—with a version of rationalism incorporating mathematical and logico-linguistic constructs and deductions of epistemology.It may be considered as a type of analytic...

by Karl Popper

Karl Popper

Sir Karl Raimund Popper, CH FRS FBA was an Austro-British philosopher and a professor at the London School of Economics...

(1902–1994) from the 1930s. Popper's model of science is one in which scientific progress

Scientific progress

Scientific progress is the idea that science increases its problem solving ability through the application of some scientific method.-Discontinuous Model of Scientific Progress:...

is achieved through a falsification

Falsification

Falsification may refer to:* The act of disproving a proposition, hypothesis, or theory: see Falsifiability* Mathematical proof* Falsified evidence...

of incorrect theories and the adoption instead of theories which are progressively closer to truth. In this model, scientific progress is a linear accumulation of facts, each one adding to the last. In this model, the physics

Physics

Physics is a natural science that involves the study of matter and its motion through spacetime, along with related concepts such as energy and force. More broadly, it is the general analysis of nature, conducted in order to understand how the universe behaves.Physics is one of the oldest academic...

of Aristotle

Aristotle

Aristotle was a Greek philosopher and polymath, a student of Plato and teacher of Alexander the Great. His writings cover many subjects, including physics, metaphysics, poetry, theater, music, logic, rhetoric, linguistics, politics, government, ethics, biology, and zoology...

(384 BC 322 BC) was simply subsumed by the work of Isaac Newton

Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton PRS was an English physicist, mathematician, astronomer, natural philosopher, alchemist, and theologian, who has been "considered by many to be the greatest and most influential scientist who ever lived."...

(1642–1727) (classical mechanics

Classical mechanics

In physics, classical mechanics is one of the two major sub-fields of mechanics, which is concerned with the set of physical laws describing the motion of bodies under the action of a system of forces...

), which itself was eclipsed by the work of Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein was a German-born theoretical physicist who developed the theory of general relativity, effecting a revolution in physics. For this achievement, Einstein is often regarded as the father of modern physics and one of the most prolific intellects in human history...

(1879–1955) (Relativity

Theory of relativity

The theory of relativity, or simply relativity, encompasses two theories of Albert Einstein: special relativity and general relativity. However, the word relativity is sometimes used in reference to Galilean invariance....

), and later the theory of quantum mechanics

Quantum mechanics

Quantum mechanics, also known as quantum physics or quantum theory, is a branch of physics providing a mathematical description of much of the dual particle-like and wave-like behavior and interactions of energy and matter. It departs from classical mechanics primarily at the atomic and subatomic...

(established in 1925), each one more accurate than the last.

A major challenge to this model came from the work of the historian and philosopher Thomas Kuhn

Thomas Kuhn

Thomas Samuel Kuhn was an American historian and philosopher of science whose controversial 1962 book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions was deeply influential in both academic and popular circles, introducing the term "paradigm shift," which has since become an English-language staple.Kuhn...

(1922–1996) in his work The Structure of Scientific Revolutions

The Structure of Scientific Revolutions

The Structure of Scientific Revolutions , by Thomas Kuhn, is an analysis of the history of science. Its publication was a landmark event in the history, philosophy, and sociology of scientific knowledge and it triggered an ongoing worldwide assessment and reaction in — and beyond — those scholarly...

published in 1962. Kuhn, a former physicist, argued against the view that scientific progress was linear, and that modern scientific theories were necessarily just more accurate versions of theories of the past. Rather, Kuhn's version of scientific development consisted of dominant structures of thought and practices, which he called "paradigm

Paradigm

The word paradigm has been used in science to describe distinct concepts. It comes from Greek "παράδειγμα" , "pattern, example, sample" from the verb "παραδείκνυμι" , "exhibit, represent, expose" and that from "παρά" , "beside, beyond" + "δείκνυμι" , "to show, to point out".The original Greek...

s", in which research went through phases of "normal

Normal science

Normal Science is a concept originated by Thomas Samuel Kuhn and elaborated in The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. The term refers to the routine work of scientists experimenting within a paradigm, slowly accumulating detail in accord with established broad theory, not actually challenging or...

" science ("puzzle solving") and "revolutionary" science (testing out new theories based on new assumptions, brought on by uncertainty and crisis in existing theories). In Kuhn's model, different paradigms represented entirely different and incommensurate

Commensurability (philosophy of science)

Commensurability is a concept in the philosophy of science. Scientific theories are described as commensurable if one can compare them to determine which is more accurate; if theories are incommensurable, there is no way in which one can compare them to each other in order to determine which is...

assumptions about the universe, and was uncertain about whether paradigms shifted in a way which necessarily relied upon greater attainment of truth. In Kuhn's view, Aristotle's physics, Newton's classical mechanics, and Einstein's Relativity were entirely different ways to think about the world; each successive paradigm defined what questions could be asked about the world and (perhaps arbitrarily) discarded aspects of the previous paradigm which no longer seemed applicable or important. Kuhn claimed that far from merely building on the previous theory's accomplishments, each one essentially throws out the old way of looking at the universe, and comes up with its own vocabulary to describe it and its own guidelines for expanding knowledge within the new paradigm

Paradigm

The word paradigm has been used in science to describe distinct concepts. It comes from Greek "παράδειγμα" , "pattern, example, sample" from the verb "παραδείκνυμι" , "exhibit, represent, expose" and that from "παρά" , "beside, beyond" + "δείκνυμι" , "to show, to point out".The original Greek...

.

Kuhn's model met with much suspicion from scientists, historians, and philosophers. Some scientists felt that Kuhn went too far in divorcing scientific progress from truth; many historians felt that his argument was too codified for something as polyvariant and historically contingent as scientific change; and many philosophers felt that the argument did not go far enough. The furthest extreme of such reasoning was put forth by the philosopher Paul Feyerabend

Paul Feyerabend

Paul Karl Feyerabend was an Austrian-born philosopher of science best known for his work as a professor of philosophy at the University of California, Berkeley, where he worked for three decades . He lived a peripatetic life, living at various times in England, the United States, New Zealand,...

(1924–1994), who argued that there were no consistent methodologies used by all scientists at all times which allowed certain forms of inquiry to be labeled "scientific" in a way which made them different from any other form of inquiry, such as witchcraft

Witchcraft

Witchcraft, in historical, anthropological, religious, and mythological contexts, is the alleged use of supernatural or magical powers. A witch is a practitioner of witchcraft...

. Feyerabend argued harshly against the notion that falsification was ever truly followed in the history of science, and noted that scientists had long undertaken practices to arbitrarily consider theories to be accurate even if they failed many sets of tests. Feyerabend argued that a pluralistic methodology should be undertaken for the investigation of knowledge, and noted that many forms of knowledge which were previously thought to be "non-scientific" were later accepted as a valid part of scientific canon.

Many other theories of scientific change have been proposed over the years with various changes of emphasis and implications. In general, though, most float somewhere between these three models for change in scientific theory, the connection between theory and truth, and the nature of scientific progress.

The nature of scientific discovery

Individual ideas and accomplishments are among the most famous aspects of science, both internally and in larger society. Prolific figures like Sir Isaac Newton, or breakthrough thinkers like Albert EinsteinAlbert Einstein

Albert Einstein was a German-born theoretical physicist who developed the theory of general relativity, effecting a revolution in physics. For this achievement, Einstein is often regarded as the father of modern physics and one of the most prolific intellects in human history...

are often celebrated as genius

Genius

Genius is something or someone embodying exceptional intellectual ability, creativity, or originality, typically to a degree that is associated with the achievement of unprecedented insight....

es and hero

Hero

A hero , in Greek mythology and folklore, was originally a demigod, their cult being one of the most distinctive features of ancient Greek religion...

es of science. Popularizers of science, including the news media and scientific biographers, contribute to this phenomenon. But many scientific historians emphasize the collective aspects of scientific discovery, and de-emphasize the importance of the "Eureka!" moment

Eureka effect

The eureka effect is any sudden unexpected discovery, or the sudden realization of the solution to a problem, resulting in a eureka moment , also dubbed as "breakthrough thinking"...

.

A detailed look at the history of science often reveals that the minds of great thinkers were primed with the results of previous efforts, and often arrive on the scene to find a crisis of one kind or another. For example, Einstein did not consider the physics of motion and gravitation in isolation. His major accomplishments solved a problem which had come to a head in the field only in recent years — empirical data showing that the speed of light was inexplicably constant, no matter the apparent speed of the observer. (See Michelson-Morley experiment

Michelson-Morley experiment

The Michelson–Morley experiment was performed in 1887 by Albert Michelson and Edward Morley at what is now Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio. Its results are generally considered to be the first strong evidence against the theory of a luminiferous ether and in favor of special...

.) Without this information, it is very unlikely that Einstein would have conceived of anything like relativity.

The question of who should get credit for any given discovery is often a source of some controversy. There are many priority disputes, in which multiple individuals or teams have competing claims over who discovered something first. Multiple simultaneous discovery is actually a surprisingly common phenomenon, perhaps largely explained by the idea that previous contributions (including the emergence of contradictions between existing theories, or unexpected empirical results) make a certain concept ready for discovery. Simple priority disputes are often a matter of documenting when certain experiments were performed, or when certain ideas were first articulated to colleagues or recorded in a fixed medium.

Many times the question of exactly which event should qualify as the moment of discovery is difficult to answer. One of the most famous examples of this is the question of the discovery of oxygen

Oxygen

Oxygen is the element with atomic number 8 and represented by the symbol O. Its name derives from the Greek roots ὀξύς and -γενής , because at the time of naming, it was mistakenly thought that all acids required oxygen in their composition...

. While Carl Wilhelm Scheele

Carl Wilhelm Scheele

Carl Wilhelm Scheele was a German-Swedish pharmaceutical chemist. Isaac Asimov called him "hard-luck Scheele" because he made a number of chemical discoveries before others who are generally given the credit...

and Joseph Priestley

Joseph Priestley

Joseph Priestley, FRS was an 18th-century English theologian, Dissenting clergyman, natural philosopher, chemist, educator, and political theorist who published over 150 works...

were able to concentrate oxygen, in the laboratory and characterize its properties, they did not recognize it as a component of air. Priestly actually thought it was missing a hypothetical component of air, known as phlogiston

Phlogiston theory

The phlogiston theory , first stated in 1667 by Johann Joachim Becher, is an obsolete scientific theory that postulated the existence of a fire-like element called "phlogiston", which was contained within combustible bodies and released during combustion...

, which air was supposed to absorb from materials that are being burned. It was only several years later that Antoine Lavoisier

Antoine Lavoisier

Antoine-Laurent de Lavoisier , the "father of modern chemistry", was a French nobleman prominent in the histories of chemistry and biology...

first conceived of the modern notion of oxygen — as a substance that is consumed from the air in the processes of burning and respiration.

By the late 20th Century, scientific research has become a large-scale effort, largely accomplished in institutional teams. The amount and frequency of inter-team collaboration has continued to increase, especially after the rise of the Internet

Internet

The Internet is a global system of interconnected computer networks that use the standard Internet protocol suite to serve billions of users worldwide...

, which is a central tool for the modern scientific community. This further complicates the notion of individual accomplishment in science.

See also

- Historiography of scienceHistoriography of scienceHistoriography is the study of the history and methodology of the discipline of history. The historiography of science is thus the study of the history and methodology of the sub-discipline of history, known as the history of science, including its disciplinary aspects and practices and to the...

- InquiryInquiryAn inquiry is any process that has the aim of augmenting knowledge, resolving doubt, or solving a problem. A theory of inquiry is an account of the various types of inquiry and a treatment of the ways that each type of inquiry achieves its aim.-Deduction:...

- Scientific methodScientific methodScientific method refers to a body of techniques for investigating phenomena, acquiring new knowledge, or correcting and integrating previous knowledge. To be termed scientific, a method of inquiry must be based on gathering empirical and measurable evidence subject to specific principles of...