Steamboats of the upper Columbia and Kootenay Rivers

Encyclopedia

_abandoned_at_golden_bc_1926_bca_b-04359.jpg)

Steamboat

A steamboat or steamship, sometimes called a steamer, is a ship in which the primary method of propulsion is steam power, typically driving propellers or paddlewheels...

s ran on the upper reaches of the Columbia

Columbia River

The Columbia River is the largest river in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. The river rises in the Rocky Mountains of British Columbia, Canada, flows northwest and then south into the U.S. state of Washington, then turns west to form most of the border between Washington and the state...

and Kootenay

Kootenay River

The Kootenay is a major river in southeastern British Columbia, Canada and the northern part of the U.S. states of Montana and Idaho. It is one of the uppermost major tributaries of the Columbia River, which is the largest North American river that empties into the Pacific Ocean...

in the Rocky Mountain Trench

Rocky Mountain Trench

The Rocky Mountain Trench, or the Trench or The Valley of a Thousand Peaks, is a large valley in the northern part of the Rocky Mountains. It is both visually and cartographically a striking physiographic feature extending approximately from Flathead Lake, Montana, to the Liard River, just south...

, in western North America. The circumstances of the rivers in the area, and the construction of transcontinental railways across the trench from east to west made steamboat navigation possible.

Geographic factors

The Columbia River begins at Columbia LakeColumbia Lake

Columbia Lake is the primary lake at the headwaters of the Columbia River, in British Columbia, Canada. It is fed by several small tributaries. The village of Canal Flats is located at the south end of the lake....

, flows north in the trench through the Columbia Valley

Columbia Valley

The Columbia Valley is the name used for a region in the Rocky Mountain Trench near the headwaters of the Columbia River between the town of Golden and the Canal Flats. The main hub of the valley is the town of Invermere. Other towns include Radium Hot Springs, Windermere and Fairmont Hot Springs...

to Windermere Lake

Windermere Lake (British Columbia)

Lake Windermere is a very large widening in the Columbia River. The village of Windermere is located on the east side of the lake, and the larger town of Invermere is located on the lake's northwestern corner...

to Golden, BC

Golden, British Columbia

Golden is a town in southeastern British Columbia, Canada, located west of Calgary, Alberta and east of Vancouver.-History:Much of the town's history is tied into the Canadian Pacific Railway and the logging industry...

. The Kootenay River flows south from the Rocky Mountains, then west into the Rocky Mountain Trench, coming within just over a mile (1.6 km) from Columbia Lake, at a point called Canal Flats

Canal Flats, British Columbia

Canal Flats is a village located at the southern end of Columbia Lake, the source of the Columbia River in British Columbia, Canada. In 2006, it had a population of 700.-Location:...

, where a shipping canal was built in 1889. The Kootenay then flows south down the Rocky Mountain Trench, crosses the international border and then turns north back into Canada and into Kootenay Lake near the town of Creston, BC

Creston, British Columbia

Creston is a town of 4,826 people in the Kootenay region of southeastern British Columbia, Canada. The town is located just a few kilometers north of the Porthill, Idaho border crossing into the United States and about a three-hour drive north from Spokane, Washington. It is about a one-hour drive...

.

The upper Columbia and the upper Kootenay rivers were different in character. From Columbia Lake to Golden, the Columbia river is shallow and slow, running through twisting channels and falling only 50 feet (15 m) in elevation from its headwaters to Golden. From Golden the river flows north to Donald, BC

Donald, British Columbia

Donald, British Columbia is located on Highway 1, 28 kilometers west of Golden. In its heyday, Donald was a divisional point on the Canadian Pacific Railway...

, then turns sharply south at the Big Bend

Big Bend Country

Big Bend Country is a term used in the Canadian province of British Columbia to refer to the region around the northernmost bend of the Columbia River, where the river leaves its initial northwestward course along the Rocky Mountain Trench to curve around the northern end of the Selkirk Mountains...

, where it continues south past Revelstoke, BC then south to south to Arrowhead

Arrowhead, British Columbia

Arrowhead is a former steamboat port and town at the head of Upper Arrow Lake in British Columbia, Canada. Though the initial site has been submerged beneath the waters of the lake, which is now part of the reservoir formed by Hugh Keenleyside Dam at Castlegar, the name continues in use as a...

, where it widens into the Arrow Lakes

Arrow Lakes

The Arrow Lakes in British Columbia, Canada, divided into Upper Arrow Lake and Lower Arrow Lake, are widenings of the Columbia River. The lakes are situated between the Selkirk Mountains to the east and the Monashee Mountains to the west. Beachland is fairly rare, and is interspersed with rocky...

. The Big Bend, in its natural state before the construction of the Revelstoke

Revelstoke Dam

The Revelstoke Dam, also known as Revelstoke Canyon Dam, is a hydroelectric dam spanning the Columbia River, 5 km north of Revelstoke, British Columbia, Canada. The powerhouse was completed in 1984 and has a generating capacity of 2480 MW. Four generating units were installed initially, with one...

and Mica dams

Mica Dam

The Mica Dam is a hydroelectric dam spanning the Columbia River 135 kilometres north of Revelstoke, British Columbia, Canada. Completed in 1973 under the terms of the 1964 Columbia River Treaty, the Mica powerhouse has a generating capacity of . The dam is operated by BC Hydro...

, included a series of rapids which made it impassable to steam navigation proceeding upriver from the Arrow Lakes.

The Kootenay River (before the construction of the Libby Dam

Libby Dam

Libby Dam is a dam on the Kootenai River in the U.S. state of Montana.Dedicated on August 24, 1975, Libby Dam spans the Kootenai River upstream from the town of Libby, Montana. Libby Dam is tall and long. Lake Koocanusa is the name of the reservoir behind the dam; it extends upriver from...

) flowed faster than the Columbia south down through Jennings Canyon, an extremely hazardous stretch of whitewater, on the way to Jennings and Libby, Montana

Libby, Montana

Libby is a city in and the county seat of Lincoln County, Montana, United States. The population was 2,626 at the 2000 census.-Geography:Libby is located at , along U.S. Route 2....

. Larger steamboats could operate on the upper Kootenay than on the upper Columbia. The Kootenay river flows on into Idaho

Idaho

Idaho is a state in the Rocky Mountain area of the United States. The state's largest city and capital is Boise. Residents are called "Idahoans". Idaho was admitted to the Union on July 3, 1890, as the 43rd state....

, where it turns north and flows back into Canada. Near Creston

Creston, British Columbia

Creston is a town of 4,826 people in the Kootenay region of southeastern British Columbia, Canada. The town is located just a few kilometers north of the Porthill, Idaho border crossing into the United States and about a three-hour drive north from Spokane, Washington. It is about a one-hour drive...

the Kootenay River enters Kootenay Lake

Kootenay Lake

Kootenay Lake is a lake located in British Columbia, Canada and is part of theKootenay River. The lake has been raised by the Corra Linn Dam and has a dike system at the southern end, which, along with industry in the 1950s-70s, has changed the ecosystem in and around the water...

. With some difficulty, steamboats could progress up the lower Kootenay to railhead

Railhead

The word railhead is a railway term with two distinct meanings, depending upon its context.Sometimes, particularly in the context of modern freight terminals, the word is used to denote a terminus of a railway line, especially if the line is not yet finished, or if the terminus interfaces with...

at Bonners Ferry, Idaho

Bonners Ferry, Idaho

Bonners Ferry is a city in and the county seat of Boundary County, Idaho, United States. The population was 2,543 at the 2010 census.-History:...

. Rapids and falls

Waterfall

A waterfall is a place where flowing water rapidly drops in elevation as it flows over a steep region or a cliff.-Formation:Waterfalls are commonly formed when a river is young. At these times the channel is often narrow and deep. When the river courses over resistant bedrock, erosion happens...

on the Kootenay blocked steam navigation between Bonner's Ferry and Libby.

Rail construction

Railhead

The word railhead is a railway term with two distinct meanings, depending upon its context.Sometimes, particularly in the context of modern freight terminals, the word is used to denote a terminus of a railway line, especially if the line is not yet finished, or if the terminus interfaces with...

s, Golden, BC and Jennings, Montana, near Libby. At Golden, the transcontinental line of the Canadian Pacific Railway ("CPR"), which parallels the Columbia south from the bridge at Donald

Donald, British Columbia

Donald, British Columbia is located on Highway 1, 28 kilometers west of Golden. In its heyday, Donald was a divisional point on the Canadian Pacific Railway...

, turns east to follow the Kicking Horse River

Kicking Horse River

The Kicking Horse River is a river located in the Canadian Rockies of southeastern British Columbia, Canada.The river was named in 1858, when James Hector, a member of the Palliser Expedition, was kicked by his packhorse while exploring the river. Hector survived and named the river and the...

, surmounting the Continental Divide

Continental Divide

The Continental Divide of the Americas, or merely the Continental Gulf of Division or Great Divide, is the name given to the principal, and largely mountainous, hydrological divide of the Americas that separates the watersheds that drain into the Pacific Ocean from those river systems that drain...

at Kicking Horse Pass

Kicking Horse Pass

Kicking Horse Pass is a high mountain pass across the Continental Divide of the Americas of the Canadian Rockies on the Alberta/British Columbia border, and lying within Yoho and Banff National Parks...

, then running past the resort at Banff

Banff, Alberta

Banff is a town within Banff National Park in Alberta, Canada. It is located in Alberta's Rockies along the Trans-Canada Highway, approximately west of Calgary and east of Lake Louise....

then east to Calgary. Jennings was reached by the Great Northern Railway, built across the Northern United States from Minnesota

Minnesota

Minnesota is a U.S. state located in the Midwestern United States. The twelfth largest state of the U.S., it is the twenty-first most populous, with 5.3 million residents. Minnesota was carved out of the eastern half of the Minnesota Territory and admitted to the Union as the thirty-second state...

to Washington by James J. Hill

James J. Hill

James Jerome Hill , was a Canadian-American railroad executive. He was the chief executive officer of a family of lines headed by the Great Northern Railway, which served a substantial area of the Upper Midwest, the northern Great Plains, and Pacific Northwest...

. Between these railheads the Rocky Mountain Trench ran for 300 miles (482.8 km), almost all of which was potentially accessible to steam navigation. Canal Flats was close to the midpoint, being just south of Columbia Lake, 124 miles (200 km) upstream from Golden.

Beginning of steam navigation

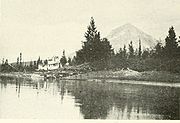

,_in_columbia_valley,_bc.jpg)

_crewman_aboard_sternwheeler_duchess,_near_golden_bc_1887.jpg)

Sawmill

A sawmill is a facility where logs are cut into boards.-Sawmill process:A sawmill's basic operation is much like those of hundreds of years ago; a log enters on one end and dimensional lumber exits on the other end....

. The result was the Duchess, launched in 1886 at Golden. Two early passengers wrote that her appearance was "somewhat decrepit" and Armstrong himself later agreed that she was "a pretty crude steamboat."

In 1886 an "uprising" among the First Nations was occurring far down the Rocky Mountain Trench along the Kootenay River. A detachment of the North-West Mounted Police, under Major (later General) Samuel Benfield Steele (1848–1919), was sent to Golden with orders to proceed to the Kootenay to quell the so-called uprising. Steele decided to hire Armstrong and the Duchess to transport his troopers. This proved to be a mistake, as once the expedition's horse fodder, ammunition, officers' uniforms, and other supplies were loaded on board, Duchess capsized and sank. After this setback, Steele decided to hire the only other steam vessel on the upper Columbia, the Clive.

Clive which like Duchess was assembled from various cast-off and second-hand components, was an even worse vessel. Once Steele had loaded his trooper's equipment on Clive, that vessel sank as well. Steele and his troop ended up riding the 150 miles (241.4 km) south to Galbraith's Landing. This took about a month. When they arrived, the troopers set up a standard military encampment which later became the town of Fort Steele. By this time, the "uprising" was over.

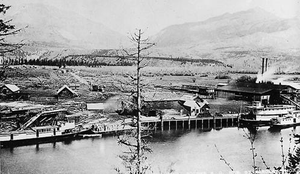

Professionally constructed steamboats appear

_at_golden_bc.jpg)

_handbill_1888_(reverse).jpg)

Victoria, British Columbia

Victoria is the capital city of British Columbia, Canada and is located on the southern tip of Vancouver Island off Canada's Pacific coast. The city has a population of about 78,000 within the metropolitan area of Greater Victoria, which has a population of 360,063, the 15th most populous Canadian...

to build the new steamer, which although small, was well-designed and looked like a steamboat instead of a floating old barn. Someone arranged to have handbills printed up, which on one side bore a woodcut print

Woodcut

Woodcut—occasionally known as xylography—is a relief printing artistic technique in printmaking in which an image is carved into the surface of a block of wood, with the printing parts remaining level with the surface while the non-printing parts are removed, typically with gouges...

showing an idealized version of the new Duchess, and on the other side bore a statement showing the company's marketing strategy

Marketing strategy

Marketing strategy is a process that can allow an organization to concentrate its limited resources on the greatest opportunities to increase sales and achieve a sustainable competitive advantage.-Developing a marketing strategy:...

, which was to appeal to tourists, miners, hunters, and intending settlers, holding out the Duchess as the best means of accessing the Columbia Valley

Columbia Valley

The Columbia Valley is the name used for a region in the Rocky Mountain Trench near the headwaters of the Columbia River between the town of Golden and the Canal Flats. The main hub of the valley is the town of Invermere. Other towns include Radium Hot Springs, Windermere and Fairmont Hot Springs...

.

The handbill then praised the climate of the Columbia Valley as "WITHOUT EXCEPTION THE FINEST ON THE CONTINENT OF AMERICA" which even so was available at $1.00 per acre, payable five years. Gold mining was said to be prosperous, with the hint of more yet to be discovered, as "the country has not been explored off the beaten paths". All kinds of supplies were to be had cheaper than they could be shipped at Golden City all kinds of supplies can be obtained more cheaply than they can be brought in "by the Tourist, Settler, or Miner". Finally, the handbill advertised the important role and schedule that the new steamer Duchess would play in the development of the Columbia Valley:

Armstrong also had built a second steamer, Marion

Marion (sternwheeler)

Marion was a small sternwheel steamboat that operated in several waterways in inland British Columbia from 1888 to 1901.-Design and Construction:...

, which although smaller than the second Duchess, needed only six inches of water to run in. This was an advantage in the often shallow waters of the Columbia above Golden, where as Armstrong put it, "the river's bottom was often very close to the river's top".

Navigation improvements

_on_columbia_river_bc_with_mudlark_(clamshell_dredge)_1898.jpg)

Anacortes, Washington

Anacortes is a city in Skagit County, Washington, United States. The name "Anacortes" is a consolidation of the name Anna Curtis, who was the wife of early Fidalgo Island settler Amos Bowman. Anacortes' population was 15,778 at the time of the 2010 census...

, are two excellent existing examples of Pacific Northwest sternwheel snagboats.) In 1892, the Dominion government put a snag boat, the Muskrat o the upper river, which must have significantly improved river transportation.

Another barrier to navigation on the upper Columbia was the numerous sandbars that were used by spawning salmon

Salmon

Salmon is the common name for several species of fish in the family Salmonidae. Several other fish in the same family are called trout; the difference is often said to be that salmon migrate and trout are resident, but this distinction does not strictly hold true...

. A clam shell dredge was employed to deepen the sandbars by digging out the river bottom. This would have had the adverse side effect of damaging the salmon spawning grounds.

Carrying the mail

_north_end_columbia_lake,_bc,_ca_1890s.jpg)

Cranbrook, British Columbia

Cranbrook, British Columbia is a city in southeast British Columbia, located on the west side of the Kootenay River at its confluence with the St. Mary's River, It is the largest urban centre in the region known as the East Kootenay. As of 2006, Cranbrook's population is 18,267, and the...

. Armstrong carried the mail twice a week on Duchess, or when the water was low, on Marion, up to Columbia Lake. Once at the lake, the steamer connected with a stage line, which ran the mail across Canal Flats and down the valley of the Kootenay River to Grohman, Fort Steele

Fort Steele, British Columbia

Fort Steele is a heritage town in the East Kootenay region of British Columbia, Canada. It is located north of the Crowsnest Highway along Highways 93 and 95, northeast of Cranbrook.-History:...

, and Cranbrook. The contract was renewed in the years from 1889 to 1992. When the mail could not be carried on the river, due to low or frozen water, Armstrong had mail carried overland on the Columbia Valley wagon road. The mail contracts were renewed from 1893 to 1897, with the mail running from Golden to the St. Eugene Mission in the Kootenay Valley. The mail contract provided an important subsidy for Captain Armstrong and the Upper Columbia Company.

Persons living along the upper Columbia who wished to mail lighters or have freight shipped would hail or flag down the mail steamer. The boat's captain would then nose the bow of the boat into the bank using the boat's sternwheel to keep the vessel in place. The mail would be picked up or the freight loaded, the fees collected, and the vessel would proceed. In April 1897 the Upper Columbia Company lost the mail contact, which created a situation where customers would flag down the steamer for a letter which the steamer was getting paid no money to carry.

Upper Columbia Company "postage stamps"

Reluctant to antagonize potential freight customers by refusing letters, but not wishing to interrupt company operations for free mail carriage, the company's purser, C.H. Parson, had the company print up its own postage stamps. One thousand "stamps" with the initials "U.C." (for Upper Columbia Company) and the denomination of 5 cents were printed. One thousand more "labels" with just the initials "U.C" were also printed. An ordinary letter in those days cost 3 cents to send, so the Upper Columbia Company's "stamps" were considerably more than regular postage. The idea seems to have been to discourage the use of the steamer for mail, and perhaps to make a little money on the side. The details of how stamps and labels were used are not clear, but clearly some did pass through the Canadian mails with additional official postage stamps also affixed. Genuine envelopes (called "covers") bearing the stamps or labels of the Upper Columbia Company are rare philatelicPhilately

Philately is the study of stamps and postal history and other related items. Philately involves more than just stamp collecting, which does not necessarily involve the study of stamps. It is possible to be a philatelist without owning any stamps...

items and are sought after by stamp collectors.

Covers bearing the labels or stamps of the Upper Columbia Company attracted the attention of stamp collectors

Stamp collecting

Stamp collecting is the collecting of postage stamps and related objects. It is one of the world's most popular hobbies, with the number of collectors in the United States alone estimated to be over 20 million.- Collecting :...

and became sought-after rarities. Faked covers have appeared, made with the objective of deceiving collectors. Knowledge of the history of the Upper Columbia Company is important to make judgment as to whether a particular cover is genuine or a fake.

The Baillie-Grohman Canal

William Adolf Baillie Grohman

William Adolph Baillie Grohman, was an Anglo-Austrian author of works on the Tyrol and the history of hunting, big game sportsman and Kootenay pioneer.-Biography:...

(1851–1921), travelled to the Kootenay Region and became obsessed with developing an area far down the Kootenay River near the southern end of Kootenay Lake

Kootenay Lake

Kootenay Lake is a lake located in British Columbia, Canada and is part of theKootenay River. The lake has been raised by the Corra Linn Dam and has a dike system at the southern end, which, along with industry in the 1950s-70s, has changed the ecosystem in and around the water...

called Kootenay Flats, near the modern town of Creston, BC

Creston, British Columbia

Creston is a town of 4,826 people in the Kootenay region of southeastern British Columbia, Canada. The town is located just a few kilometers north of the Porthill, Idaho border crossing into the United States and about a three-hour drive north from Spokane, Washington. It is about a one-hour drive...

. The problem for Baillie-Grohman was that the Kootenay River kept flooding Kootenay Flats. Baillie-Grohman thought the downstream flooding could be lessened by diverting the upstream portion of the Kootenay River into the Columbia River through the Canal Flats. This would have increased the water flow through the Columbia River, particularly near Golden and Donald, where Baillie-Grohman's proposal, if it had been implemented, would have threatened to flood the newly built transcontinental railroad and other areas of the Columbia Valley.

The provincial government refused to allow the diversion. However, Baillie-Grohman was able to obtain ownership of large areas of land in the Kootenay region, provided he engaged in certain forms of economic development, including construction of a shipping canal

Canal

Canals are man-made channels for water. There are two types of canal:#Waterways: navigable transportation canals used for carrying ships and boats shipping goods and conveying people, further subdivided into two kinds:...

and a lock. The lock was necessary because the Kootenay River was 11 ft (3.4 m) than the level of Columbia Lake.

The Baillie-Grohman canal was used only three times by steam-powered vessels. In 1893, Armstrong built Gwendoline

Gwendoline (sternwheeler)

Gwendoline was a sternwheel steamer that operated on the Kootenay River in British Columbia and northwestern Montana from 1893 to 1899. The vessel was also operated briefly on the Columbia River in the Columbia Valley.-Design and construction:...

at Hansen's Landing on the Kootenay River, and took the vessel through the canal north to the shipyard at Golden to complete her fitting out. In late May 1894 Armstrong returned the completed Gwendoline back to the Kootenay River, transiting the canal.

The canal remained unused until 1902, Armstrong brought North Star

North Star (sternwheeler 1897)

North Star was a sternwheel steamer that operated in western Montana and southeastern British Columbia on the Kootenay and Columbia rivers from 1897 to 1903. The vessel should not be confused with other steamers of the same name, some of which were similarly designed and operated in British...

north from the Kootenay to the Columbia. The transit of North Star was only made possible by the destruction of the lock at the canal, thus making it unusable.

The Upper Columbia Navigation and Tramway Company

The Upper Columbia Company built two horse or mule-drawn tram

Tram

A tram is a passenger rail vehicle which runs on tracks along public urban streets and also sometimes on separate rights of way. It may also run between cities and/or towns , and/or partially grade separated even in the cities...

ways, one at the start of the route running from the CPR depot at Golden Station to the point 2 miles (3 km) south where the Kicking Horse River

Kicking Horse River

The Kicking Horse River is a river located in the Canadian Rockies of southeastern British Columbia, Canada.The river was named in 1858, when James Hector, a member of the Palliser Expedition, was kicked by his packhorse while exploring the river. Hector survived and named the river and the...

ran into the Columbia. It was here that the company had located its steamboat dock.

The second tramway was located further upriver. It ran 5 miles (8 km) in length, from Adela Lake, BC. south to Columbia Lake. The tramways were like railways except that the cars were horsedrawn, and the carts were much smaller than rail cars. The company had steamers on Columbia Lake and the Kootenay River, but did not use the Grohman Canal, portaging traffic over Canal Flats rather than using the canal, which in fact was only used twice by steamboats during its existence.

With the tramways in place, the 300 mile transportation chain from the rail depot at Golden to Jennings Montana ran as follows. Freight would be taken on the tramway to the steamboat dock at Golden, and loaded on a steamer. The steamer ran upriver to the south end of Windermere Lake. The freight would then be portaged around Mud (or Adlin) Lake, to Columbia Lake. Once at Columbia Lake, the cargo would be loaded again on a steamboat, this time the Pert and run to the south end of Columbia Lake, where it was unloaded again, portaged across Canal Flats and loaded again on another steamer on the Kootenay river, and run down to Jennings, passing through Jennings Canyon.

Steam navigation begins on the upper Kootenay River

_on_kootenay_river_1893_bca_g-00277.jpg)

Railhead

The word railhead is a railway term with two distinct meanings, depending upon its context.Sometimes, particularly in the context of modern freight terminals, the word is used to denote a terminus of a railway line, especially if the line is not yet finished, or if the terminus interfaces with...

was that of the Great Northern Railway at Jennings, Montana, well over 100 miles (160.9 km) away from the major mining strikes at Kimberly and Moyie Lake

Moyie Lake

Moyie Lake is a small, narrow lake in southern British Columbia, located along the Moyie River. While building the Crowsnest Pass Railroad, this was the hardest part to build the tracks. The walls of the land around it is very steep and short. It is a lot like Swan Lake to the south in Montana. ...

. Overland transport out of the question. The ore could only be moved by marine transport on the Kootenay River. With this in mind, Walter Jones and Captain Harry S. DePuy organized the Upper Kootenay Navigation Company ("UKNC") and in the winter of 1891 to 1892, built at Jennings the small sternwheeler Annerly

Annerly (sternwheeler)

Annerly was a sternwheel steamboat that operated on the upper Kootenay River in British Columbia and northwestern Montana from 1892 to 1896.-Design and Construction:...

. With the spring breakup of the ice in 1893, DePuy and Jones were able to get Annerly 130 miles (209.2 km) upriver to Quick Ranch, about 15 miles (24 km) south of Fort Steele, BC

Fort Steele, British Columbia

Fort Steele is a heritage town in the East Kootenay region of British Columbia, Canada. It is located north of the Crowsnest Highway along Highways 93 and 95, northeast of Cranbrook.-History:...

. Once there, Annerly was able to embark passengers and load 50 short tons (45,359.2 kg) of ore. Returning to Jennings, Jones and DePuy were able to make enough money to hire veteran James D. Miller (1830–1907), one of the most experienced steamboat men in the Pacific Northwest, to hand Annerly for the rest of the 1893 season.

Rise of competition on the Kootenay River

Armstrong also wished to take advantage of the demand for shipping, so moving south from the Columbia to the Kootenay, he built the small sternwheeler GwendolineGwendoline (sternwheeler)

Gwendoline was a sternwheel steamer that operated on the Kootenay River in British Columbia and northwestern Montana from 1893 to 1899. The vessel was also operated briefly on the Columbia River in the Columbia Valley.-Design and construction:...

at Hansen's Landing, about 12 miles (19 km) north of the present town of Wasa

Wasa, British Columbia

Wasa is an unincorporated settlement in the East Kootenay region of British Columbia, Canada, located on the east bank of the Kootenay River to the north of Fort Steele. It was named for Vasa, Finland, the hometown of one of the community's early pioneers, Nils Hansen.-Climate:-References:...

. Instead of taking the ore south to Jennings, Armstrong's plan was to move the ore north across Canal Flats and then down the Columbia to the CPR railhead at Golden. As described, Armstrong took Gwendoline through the Baillie-Grohman canal in the fall of 1893 (or rolled her across Canal Flats), fitted her out at Golden, and returned back through the canal in the spring of 1894.

In March 1896, Miller shifted over to run Annerly as an associate of Armstrong's Upper Columbia Navig. & Tramway Co. In 1896, Armstrong and Miller built Ruth at Libby, Montana

Libby, Montana

Libby is a city in and the county seat of Lincoln County, Montana, United States. The population was 2,626 at the 2000 census.-Geography:Libby is located at , along U.S. Route 2....

. Launched April 22, 1896, Ruth at 275 tons was the largest steamer yet to operate on the upper Kootenay River. Ruth, like the second Duchess, was designed and built by a professional shipwright. For Ruth the shipwright Louis Pacquet, of Portland, Oregon

Portland, Oregon

Portland is a city located in the Pacific Northwest, near the confluence of the Willamette and Columbia rivers in the U.S. state of Oregon. As of the 2010 Census, it had a population of 583,776, making it the 29th most populous city in the United States...

. Ruth made the runs downriver to Jennings and the smaller Gwendoline ran upriver with the traffic to Canal Flats and the portage tramway.

The combination of Armstrong, Miller and Wardner, and their construction of Ruth created serious competition for Jones and DePuy of UKNC with their only steamer the barely-adequate Annerly. Large sacks of ore were piling up at Hansen's Landing from the mines, and all needed transport. The competitors reached an agreement to split the traffic on the Kootenay river between them. To earn their share of the revenues from this split, DePuy and Jones built Rustler (125 tons) at Jennings 1896. Rustler reached Hansen's Landing in June 1896 on her run up from Jennings.

Another competitor was Captain Tom Powers, of Tobacco Plain, Montana who traded 15 cayuse

Cayuse

The Cayuse are a Native American tribe in the state of Oregon in the United States. The Cayuse tribe shares a reservation in northeastern Oregon with the Umatilla and the Walla Walla tribes as part of the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation...

horses for the machinery to build a small steamer near Fort Steele, which was called Fool Hen. The machinery was too large for Fool Hen and there was no room for freight. Powers used discarded wooden packing cases from Libby merchants to make his paddlewheel buckets, so that as the steamer churned down the river, the merchants' names rotated again and again as the wheel turned. Shortly after Fool Hen was finished, Powers then removed the engines and placed them in a new steamer, the Libby. This time the engines proved to be too small for the hull, and Libby was used only sporadically in 1894 and 1895.

Jennings Canyon

_at_jennings_montana_ca_1900.jpg)

Libby Dam

Libby Dam is a dam on the Kootenai River in the U.S. state of Montana.Dedicated on August 24, 1975, Libby Dam spans the Kootenai River upstream from the town of Libby, Montana. Libby Dam is tall and long. Lake Koocanusa is the name of the reservoir behind the dam; it extends upriver from...

, flowed through Jennings Canyon to the settlement of Jennings, Montana. Jennings has almost completely disappeared as a town, but it was near Libby, Montana

Libby, Montana

Libby is a city in and the county seat of Lincoln County, Montana, United States. The population was 2,626 at the 2000 census.-Geography:Libby is located at , along U.S. Route 2....

. Above Jennings, the Kootenay River narrowed as it ran through Jennings Canyon, which was a significant hazard to any river navigation. A particularly dangerous stretch was known as the Elbow. Jennings Canyon was described by Professor Lyman as "a strip of water, foaming-white, downhill almost as on a steep roof, hardly wider than steamboat".

No insurance agent would write a policy for steamboats and cargo transiting the Jennings Canyon. Captain Armstrong once persuaded an agent from San Francisco to consider making a quote on premiums. The agent decided to examine the route for himself, and went on board with Armstrong as the captain's boat shot through the canyon. At the end of the trip, the agent's quote for a policy was one-quarter of the value of the cargo. Faced with this quote, Armstrong decided to forego insurance.

The huge profits to be made seemed to justify the risk. Combined the two steamers could earn $2,000 in gross receipts per day, a lot of money in 1897. By comparison, the sternwheeler J.D. Farrell

J.D. Farrell (sternwheeler)

J.D. Farrell was a sternwheel steamer that operated on the Kootenay River in western Montana and southeastern British Columbia from 1898 to 1902.-Design and Construction:...

(1897), cost $20,000 to build in 1897. In ten days of operation then, an entire steamboat could be paid for.

There were no more than seven steamboats that ever passed through Jennings Canyon, Annerly, Gwendoline, Libby, Rustler, Ruth, J.D. Farrell

J.D. Farrell (sternwheeler)

J.D. Farrell was a sternwheel steamer that operated on the Kootenay River in western Montana and southeastern British Columbia from 1898 to 1902.-Design and Construction:...

, and North Star (1897). Of these only Annerly and Libby were not wrecked in the canyon. Armstrong and Miller unsuccessfully tried to get the U.S. Government to finance clearing of some of the rocks and obstructions in Jennings Canyon. Without government help, they hired crews themselves to do the work over two winters, but the results were not of much value.

Rustler was the first steamboat casualty of Jennings Canyon. In the summer of 1896, after just six weeks of operation, Rustler was caught in an eddy in the canyon swirled around and smashed into the rocks and damaged beyond repair. This left DePuy and Jones with just one vessel, the "nasty little Annerly", as historian D.M. Wilson described her. DePuy and Jones were unable to stay in business after the loss of Rustler and were forced to sell their facilities at Jennings, as well as Annerly to Armstrong, Miller and Wardner. With their principal competitors gone, Armstrong, Miller and Wardner incorporated their firm on April 5, 1897, in the state of Washington, as the International Transportation Company ("ITC") with nominal headquarters in Spokane

Spokane, Washington

Spokane is a city located in the Northwestern United States in the state of Washington. It is the largest city of Spokane County of which it is also the county seat, and the metropolitan center of the Inland Northwest region...

. With salvaged machinery from Rustler, they built North Star

North Star (sternwheeler 1897)

North Star was a sternwheel steamer that operated in western Montana and southeastern British Columbia on the Kootenay and Columbia rivers from 1897 to 1903. The vessel should not be confused with other steamers of the same name, some of which were similarly designed and operated in British...

, launching the new vessel at Jennings on May 28, 1897.

The wreck of Gwendoline and Ruth on May 7, 1897, was perhaps the most spectacular. With no insurance coverage, both Ruth and Gwendoline were running through Jennings Canyon. Ruth under Capt. Sanborn was about an hour ahead of Gwendoline, under Armstrong himself. Both steamers were heavily loaded, and a 26 car train was waiting at Jennings to receive their cargo. Ruth came to the Elbow, lost control, and came to rest blocking the main channel. Gwendoline came through at high speed, and could not avoid smashing into Ruth. Fortunately no one was killed. However, Ruth was totally destroyed, Gwendoline was seriously damaged, and the cargoes on both steamers were lost. Fortunately for the company, the North Star was near to being complete when the disaster occurred. Once North Star was launched, Armstrong was able to complete 21 round trips on the Kootenay before low water forced him to tie up on September 3, 1897.

Steam navigation ends on upper Kootenay river

_on_columbia_river_ca_1902.jpg)

Klondike Gold Rush

The Klondike Gold Rush, also called the Yukon Gold Rush, the Alaska Gold Rush and the Last Great Gold Rush, was an attempt by an estimated 100,000 people to travel to the Klondike region the Yukon in north-western Canada between 1897 and 1899 in the hope of successfully prospecting for gold...

, with Armstrong deciding to try his chances at making money as a steamboat captain on the Stikine River

Stikine River

The Stikine River is a river, historically also the Stickeen River, approximately 610 km long, in northwestern British Columbia in Canada and southeastern Alaska in the United States...

then being promoted as the "All-Canadian" route to the Yukon River

Yukon River

The Yukon River is a major watercourse of northwestern North America. The source of the river is located in British Columbia, Canada. The next portion lies in, and gives its name to Yukon Territory. The lower half of the river lies in the U.S. state of Alaska. The river is long and empties into...

gold fields.

J.D. Farrell, the largest steamboat ever built on either the upper Kootenay or Columbia Rivers, and sporting such frontier luxuries as bathrooms, electric lighting, and steam heat, reached Fort Steele on April 28, 1898, her first trip up the Kootenay. Built to last ten years, this fine steamer was to run for only a single season on the Kootenay. On June 8, 1898, Captain McCormack was taking J.D. Farrell south through Jennings Canyon in "hurricane" strength headwind, which blew her off course into a rock, knocking a hole in the stern. McCormack managed to get the steamer to shallow water before she sank up to the wheelhouse. Her owners were able to raise J.D. Farrell and make a few more trips that season.

By October 1898 enough rail lines were completed along the upper Kootenay to terminate steam navigation as an competitive transportation method. In particular, the completion of Crow's Nest Railway on October 6, 1898, and development of smelters in the Kootenay region, particularly at Trail, BC

Trail, British Columbia

Trail is a city in the West Kootenay region of the Interior of British Columbia, Canada.-Geography:Trail has an area of . The city is located on both banks of the Columbia River, approximately 10 km north of the United States border. This section of the Columbia River valley is located between the...

, near the southern end of the Arrow Lakes, allowed ore to be routed to smelters by rail, completely bypassing Jennings.

The surviving upper Kootenay boats, North Star, J.D. Farrell, and Gwendoline were laid up at Jennings. (Annerly had been dismantled by then.) J.D. Farrell and North Star were tied up for almost three years at Jennings until finding employment supporting construction of a rail line to Fernie, BC

Fernie, British Columbia

Fernie is a city in the Elk Valley area of the East Kootenay region of southeastern British Columbia, Canada, located on BC Highway 3 on the eastern approaches to the Crowsnest Pass through the Rocky Mountains...

. J.D. Farrell was later dismantled, with engines and machinery being reused on another steamer. (This was the general practice.) North Star was sold back to Captain Armstrong when he returned from his Yukon adventure, and on June 4, 1902, he took her north to the Columbia River on his famous dynamite-aided transit of the decrepit Baillie-Grohman canal. With North Star gone, steamboating on the upper Kootenay ended for good.

Of the last three Kootenay boats, Gwendolines fate was unique. When Armstrong and Wardner left ITC for the north, James D. Miller was in charge of the ITC boats. Striking on the idea of moving Gwendoline to the lower Kootenay River by rail, where she could be run profitably again, or at least so it was hoped. In June 1899 he had the vessel loaded on three flat cars. Disaster then struck when the vessel was shifted to fit around a trackside rock cut. The boat was moved too close to the edge, flipped off the rail cars and landed in a canyon, which the Libby Press described:

Later operations on the upper Columbia River

_on_columbia_river_ca_1910.jpg)

Selkirk (sternwheeler 1895)

Selkirk was a small sternwheel steamer that operated on the Thompson and Columbia rivers in British Columbia from 1895 to 1917. This vessel should not be confused with the much larger Yukon River sternwheeler Selkirk.-Design and construction:...

by rail from Shuswap Lake

Shuswap Lake

Shuswap Lake is a lake located in south-central British Columbia, Canada that drains via the Little River into Little Shuswap Lake. Little Shuswap Lake is the source of the South Thompson River, a branch of the Thompson River, a tributary of the Fraser River...

to Golden, where he launched her but used her as a yacht and not, at least initially, as commercial vessel. Also, Captain Alexander Blakely bought the little sidewheeler Pert

Pert (sidewheeler)

Pert was a sidewheel steamboat that operated in British Columbia on the Columbia River from 1887 to 1905, often carrying a lot of timber. Pert was also known as Alert, Perty, Papa P, P Dog and City of Windermere at times....

and operated her on the river. In 1899 Duchess became involved in the Stolen Church Affair

Donald, British Columbia

Donald, British Columbia is located on Highway 1, 28 kilometers west of Golden. In its heyday, Donald was a divisional point on the Canadian Pacific Railway...

, in which a dispute arose over ownership of a church in Donald, with one party packing up the entire church and moving it to Golden, and disputant party removing the bell from the church while en route to Golden on board Duchess. (The church itself was later moved to Windermere, without the bell.)

In 1902 Duchess was dismantled. In 1903 Captain Armstrong built a new steamer, Ptarmigan

Ptarmigan (sternwheeler)

Ptarmigan was a sternwheel steamboat that operated in British Columbia on the Columbia River from 1903 to 1909.-Design and Construction:Ptarmigan was built at Golden, BC and was the last vessel built for the Upper Columbia Navig. & Tramway Co., of which Capt. Frank P. Armstrong was the principal...

, using the engines from Duchess which by then were over 60 years old. In 1911, the same engines were installed in the newly-built steamer Nowitka

Nowitka (sternwheeler)

Nowitka was a sternwheel steamboat that operated in British Columbia on the Columbia River from 1911 to May 1920. The name is a Chinook Jargon word usually translated as "Indeed!" or "Verily!".-Design and construction:...

. With the construction of railroads, and economic dislocation caused by Canada's participation in the Great War, steamboat activity tapered off starting about 1915. Steamboat men from the route themselves went to war. Captain Armstrong supervised British river transport in the Middle East, on the Nile and Tigris river. Captain Blakey's son John Blakely (1889–1963), who had trained under his father and Captain Armstrong, went to Europe and was one of only six survivors when his ship was torpedo

Torpedo

The modern torpedo is a self-propelled missile weapon with an explosive warhead, launched above or below the water surface, propelled underwater towards a target, and designed to detonate either on contact with it or in proximity to it.The term torpedo was originally employed for...

ed in the English Channel

English Channel

The English Channel , often referred to simply as the Channel, is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that separates southern England from northern France, and joins the North Sea to the Atlantic. It is about long and varies in width from at its widest to in the Strait of Dover...

.

Last steamboat runs on the upper Columbia river

Nowitka made the last steamboat run on the upper Columbia in May 1920, when under Captain Armstrong she pushed a pile-driverPile driver

A pile driver is a mechanical device used to drive piles into soil to provide foundation support for buildings or other structures. The term is also used in reference to members of the construction crew that work with pile-driving rigs....

to build a bridge at Brisco NW of Invermere

Invermere, British Columbia

Invermere is a community in eastern British Columbia, Canada, near the border of Alberta. With its growing permanent population of almost 4,000 , swelling to near 40,000 on summer weekends, it is the hub of the Columbia Valley between Golden, and Cranbrook...

, which when complete was too low to allow a steamboat to pass under it. Armstrong himself had found employment with the Dominion government on his return from the war. He was seriously injured in an accident in Nelson, BC

Nelson, British Columbia

Nelson is a city located in the Selkirk Mountains on the extreme West Arm of Kootenay Lake in the Southern Interior of British Columbia, Canada. Known as "The Queen City", and acknowledged for its impressive collection of restored heritage buildings from its glory days in a regional silver rush,...

and died in a hospital in Vancouver, BC in January 1923. His own life had spanned the entire history of steam navigation in the Rocky Mountain Trench from 1886 to 1920. In 1948, Captain John Blakely built a sternwheeler of his own, the Radium Queen, which had to be small to fit under the Brisco bridge.

Modern archaeological investigations

Lists of vessels

| Name | Year Built | Registra- tion # |

Mills # | Gross Tons | Reg. Tons | Length | Beam | Depth | Engines | Disposition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Duchess (1886) |

1886 | 32 | 60 ft (18 m) | 17 ft (5 m) | 4 ft (1 m) | 8" x 30" | Dismantled 1888, engines to Duchess (1888) | |||

| Clive | 1879 | 20 | 31 ft (9 m) | 9.3 ft (3 m) | 4 ft (1 m) | single cylinder 5.5" x 8" | Sank near Spillmacheen 1887. | |||

_at_golden_bc.jpg) Duchess (1888) |

1888 | 90800 | 014610 | 145.5 | 99.5 | 81.6 ft (25 m) | 17.3 ft (5 m) | 4.6 ft (1 m) | 8" x 30" | Dismantled 1901 or 1902, engines to Ptarmigan Ptarmigan (sternwheeler) Ptarmigan was a sternwheel steamboat that operated in British Columbia on the Columbia River from 1903 to 1909.-Design and Construction:Ptarmigan was built at Golden, BC and was the last vessel built for the Upper Columbia Navig. & Tramway Co., of which Capt. Frank P. Armstrong was the principal... |

_ca_1890s.jpg) Marion Marion (sternwheeler) Marion was a small sternwheel steamboat that operated in several waterways in inland British Columbia from 1888 to 1901.-Design and Construction:... |

1888 | 94801 | 035040 | 14.8 | 9.3 | 61 ft (19 m) | 10.3 ft (3 m) | 3.6 ft (1 m) | 5.5" x 8" | Transferred to Arrow Lakes Arrow Lakes The Arrow Lakes in British Columbia, Canada, divided into Upper Arrow Lake and Lower Arrow Lake, are widenings of the Columbia River. The lakes are situated between the Selkirk Mountains to the east and the Monashee Mountains to the west. Beachland is fairly rare, and is interspersed with rocky... 1890. |

_at_canal_flats_1894.jpg) Pert Pert (sidewheeler) Pert was a sidewheel steamboat that operated in British Columbia on the Columbia River from 1887 to 1905, often carrying a lot of timber. Pert was also known as Alert, Perty, Papa P, P Dog and City of Windermere at times.... |

1890 | 107826 | 042920 | 6.5 | 4.0 | 49.8 ft (15 m) | 10 ft (3 m) | 2.6 ft (0.79248 m) | 5" x 6" | abandoned at Windermere Lake Windermere Lake (British Columbia) Lake Windermere is a very large widening in the Columbia River. The village of Windermere is located on the east side of the lake, and the larger town of Invermere is located on the lake's northwestern corner... 1905 |

Hyak Hyak (sternwheeler) Hyak was a sternwheel steamboat that operated in British Columbia on the Columbia River from 1892 to 1906. Hyak should not be confused with the Puget Sound propeller-driven steamboat also named Hyak. The name means "swift" or "fast" in the Chinook Jargon.-Design and construction:Hyak was built at... |

1892 | 100637 | 024760 | 39 | 24.6 | 81 ft (25 m) | 11.2 ft (3 m) | 3.9 ft (1 m) | 6" x 24" | Laid up 1906 |

_on_columbia_river,_bc_ca_1896.jpg) Gwendoline Gwendoline (sternwheeler) Gwendoline was a sternwheel steamer that operated on the Kootenay River in British Columbia and northwestern Montana from 1893 to 1899. The vessel was also operated briefly on the Columbia River in the Columbia Valley.-Design and construction:... |

1893 | 100805 | 022400 | 91 | 57 | 63.5 ft (19 m) | 19 ft (6 m) | 3.2 ft (0.97536 m) | 8" x 36" | Returned to Kootenay River, spring 1894 (see chart below for final disposition). |

_in_british_columbia_ca_1900.jpg) Selkirk 1895 Selkirk (sternwheeler 1895) Selkirk was a small sternwheel steamer that operated on the Thompson and Columbia rivers in British Columbia from 1895 to 1917. This vessel should not be confused with the much larger Yukon River sternwheeler Selkirk.-Design and construction:... |

1899 | 103299 | 050990 | 58.5 | 37.5 | 62 ft (19 m) | 11.2 ft (3 m) | 3.6 ft (1 m) | 5" x 24" | Abandoned 1917 at Golden shipyard, still visible on ways in 1926 |

_on_kootenay_river_at_fort_steele.jpg) North Star North Star (sternwheeler 1897) North Star was a sternwheel steamer that operated in western Montana and southeastern British Columbia on the Kootenay and Columbia rivers from 1897 to 1903. The vessel should not be confused with other steamers of the same name, some of which were similarly designed and operated in British... |

1897 | US 130739 | 380 | 265 | 130 ft (40 m) | 26 ft (8 m) | 4 ft (1 m) | 14" x 48" | Transited Baillie-Grohman Canal in 1902 from Kootenay River to Columbia River. Technically under customs seizure at Golden in 1903; laid up and gradually dismantled with parts to other steamers. | |

_on_columbia_river_ca_1905.jpg) Ptarmigan Ptarmigan (sternwheeler) Ptarmigan was a sternwheel steamboat that operated in British Columbia on the Columbia River from 1903 to 1909.-Design and Construction:Ptarmigan was built at Golden, BC and was the last vessel built for the Upper Columbia Navig. & Tramway Co., of which Capt. Frank P. Armstrong was the principal... |

1903 | 111950 | 044870 | 246.5 | 155 | 110.5 ft (34 m) | 20.5 ft (6 m) | 4 ft (1 m) | 8" x 30" | Dismantled 1909, engines to Nowitka Nowitka (sternwheeler) Nowitka was a sternwheel steamboat that operated in British Columbia on the Columbia River from 1911 to May 1920. The name is a Chinook Jargon word usually translated as "Indeed!" or "Verily!".-Design and construction:... . |

_entering_windermere_lake,_bc_ca_1912_bca_a-01662.jpg) Isabella McCormack Isabella McCormack (sternwheeler) Isabella McCormack was a sternwheel steamboat that operated in British Columbia on the Columbia River from 1908 to 1910... |

1908 | 122399 | 025730 | 178 | 112 | 94.9 ft (29 m) | 18.8 ft (6 m) | 3.5 ft (1 m) | 7" x 42" | Beached 1910 at Althalmer, BC, and converted to houseboat. Engines to Klahowya Klahowya (sternwheeler) Klahowya was a sternwheel steamer that operated in British Columbia on the Columbia River from 1910 to 1915. The name "Klahowya" is the standard greeting in the Chinook Jargon.-Design and construction:... . |

_leaving_golden,_bc_ca_1911.jpg) Klahowya Klahowya (sternwheeler) Klahowya was a sternwheel steamer that operated in British Columbia on the Columbia River from 1910 to 1915. The name "Klahowya" is the standard greeting in the Chinook Jargon.-Design and construction:... |

1910 | 126946 | 029880 | 175 | 111 | 92 ft (28 m) | 19 ft (6 m) | 3.5 ft (1 m) | 7" x 42" | Laid up 1915 |

| Nowitka Nowitka (sternwheeler) Nowitka was a sternwheel steamboat that operated in British Columbia on the Columbia River from 1911 to May 1920. The name is a Chinook Jargon word usually translated as "Indeed!" or "Verily!".-Design and construction:... |

1913 | 130604 | 040720 | 82 | 62 | 80.5 ft (25 m) | 19 ft (6 m) | 3.5 ft (1 m) | 8" x 30" | laid up May 1920 |

_with_barge_columbia_river_bc_ca_1918_na-852-2.jpg) F.P. Armstrong |

1913 | 134032 | 017430 | 126 | 79 | 81 ft (25 m) | 20 ft (6 m) | 4 ft (1 m) | 12" x 72" | Abandoned near Fairmont Hot Springs, BC Fairmont Hot Springs, British Columbia Fairmont Hot Springs is an unincorporated community located in south-eastern British Columbia, Canada. This community has a population of 489, but receives many vacationers from Calgary, who come to play on Fairmont's three golf courses on the Columbia River, and visit the Fairmont Hot Springs... ca 1920. |

_near_golden_bc,_ca_1912.jpg) Invermere Invermere (riverboat) Invermere was a river boat that operated in British Columbia on the Columbia River from 1912 to about 1915. It was named for the town of Invermere.-Design and Construction:... |

1912 | 130892 | 025370 | 66 | 75 ft (23 m) | 13 ft (4 m) | 4 ft (1 m) | propeller-driven, gasoline or diesel engine | ||

| Muskrat (1892) | 1892 | none | 038440 | 84 ft (26 m) | 20 ft (6 m) | Dominion government snag boat | ||||

| Name | Year Built | Registra- tion # |

Jones # | Gross Tons | Reg. Tons | Length | Beam | Depth | Engines | Disposition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

_on_kootenay_river_1893_bca_g-00277.jpg) Annerly Annerly (sternwheeler) Annerly was a sternwheel steamboat that operated on the upper Kootenay River in British Columbia and northwestern Montana from 1892 to 1896.-Design and Construction:... |

1892 | US #106963 | 128 | 80 | 92.5 ft (28 m) | 16 ft (5 m) | 4.4 ft (1 m) | Broken up 1896 | ||

| Gwendoline Gwendoline (sternwheeler) Gwendoline was a sternwheel steamer that operated on the Kootenay River in British Columbia and northwestern Montana from 1893 to 1899. The vessel was also operated briefly on the Columbia River in the Columbia Valley.-Design and construction:... |

1893 | 100805 | 022400 | 91 | 57 | 63.5 ft (19 m) | 19 ft (6 m) | 3.2 ft (0.97536 m) | 8" x 36" | Toppled off flat car during rail transfer to lower Kootenay River, June 1899, fell in canyon and was total loss |

| Fool Hen | 1894 | Dismantled, engines to Libby | ||||||||

| Libby | 1895 | steam engine Steam engine A steam engine is a heat engine that performs mechanical work using steam as its working fluid.Steam engines are external combustion engines, where the working fluid is separate from the combustion products. Non-combustion heat sources such as solar power, nuclear power or geothermal energy may be... |

||||||||

| Rustler | 1896 | US 111114 | 258 | 196 | 124 ft (38 m) | 22 ft (7 m) | 4 ft (1 m) | 10" x 72" | Wrecked in Jennings Canyon, 1896 for total loss, after being in service only 6 weeks. | |

| Ruth | 1896 | US 111113 | 315 | 275 | 131 ft (40 m) | 22 ft (7 m) | 4.5 ft (1 m) | 10" x 74" | lost control at The Elbow in Jennings Canyon and demolished in following collision with Gwendoline Gwendoline (sternwheeler) Gwendoline was a sternwheel steamer that operated on the Kootenay River in British Columbia and northwestern Montana from 1893 to 1899. The vessel was also operated briefly on the Columbia River in the Columbia Valley.-Design and construction:... , 1897 |

|

_at_jennings_montana_ca_1900.jpg) J.D. Farrell J.D. Farrell (sternwheeler) J.D. Farrell was a sternwheel steamer that operated on the Kootenay River in western Montana and southeastern British Columbia from 1898 to 1902.-Design and Construction:... |

1897 | 100687 | 359 | 226 | 130 ft (40 m) | 26 ft (8 m) | 4.5 ft (1 m) | Dismantled 1903, engines, boiler, fitting and major parts of superstructure to Lake Pend Oreille Lake Pend Oreille Lake Pend Oreille is a lake in the northern Idaho Panhandle, with a surface area of . It is 65 miles long, and 1,150 feet deep in some regions, making it the fifth deepest in the United States. It is fed by the Clark Fork River and the Pack River, and drains via the Pend Oreille River... sternwheeler Spokane (1903). |

||

_on_columbia_river_ca_1902.jpg) North Star North Star (sternwheeler 1897) North Star was a sternwheel steamer that operated in western Montana and southeastern British Columbia on the Kootenay and Columbia rivers from 1897 to 1903. The vessel should not be confused with other steamers of the same name, some of which were similarly designed and operated in British... |

1897 | 130739 | 380 | 265 | 130 ft (40 m) | 26 ft (8 m) | 4 ft (1 m) | 14" x 48" | Transited Baillie-Grohman Canal in 1902 to Columbia River. See table above for ultimate disposition. | |

See also

- Frank P. ArmstrongFrank P. ArmstrongFrancis Patrick Armstrong was a steamboat captain in the East Kootenay region of British Columbia. He also operated steamboats on the Kootenay River in Montana and on the Stikine River in western British Columbia. Steam navigation in the Rocky Mountain Trench which runs through the East Kootenay...

- Baillie-Grohman CanalBaillie-Grohman CanalThe Baillie-Grohman Canal was a shipping canal between the headwaters of the Columbia River and the upper Kootenay River in the East Kootenay region of British Columbia at a place now known as Canal Flats, BC...

- Steamboats of the Arrow LakesSteamboats of the Arrow LakesThe era of steamboats on the Arrow Lakes and adjoining reaches of the Columbia River is long-gone but was an important part of the history of the West Kootenay and Columbia Country regions of British Columbia. The Arrow Lakes are formed by the Columbia River in southeastern British Columbia...

- Steamboats of the Upper Fraser River

- Steamboats of the Columbia RiverSteamboats of the Columbia RiverMany steamboats operated on the Columbia River and its tributaries, in the Pacific Northwest region of North America, from about 1850 to 1981. Major tributaries of the Columbia that formed steamboat routes included the Willamette and Snake rivers...

External links

- Fort Steele Heritage Town, map and diagram page Contains period maps of East Kootenay region, including original maps and later working diagrams of the Baillie-Grohman canal.

- Taming the Kootenay, Creston and District Historical and Museum Society Multi-media presentation of history of Canal Flats and the East Kootenay region

- Columbia Basin Institute of Regional History

- Crowsnest Railway Route

- SS Moyie National Historical Site Oldest surviving sternwheeler in the Pacific Northwest and in Canada. Last surviving steernwheeler of the entire Kootaney-Arrow Lakes region.

Further reading

- Kluckner, Michael, Vanishing British Columbia, University of British Columbia Press, Vancouver BC, 2005 ISBN 0-295-98493-7

- Lees, J.A., and Clutterbuck, W.J., B.C. 1887—A Ramble In British Columbia, Longman, Greens & Co., London 1888.