.gif)

John Fowler (engineer)

Encyclopedia

Sir John Fowler, 1st Baronet KCMG

LLD

(15 July 1817 – 20 November 1898) was an English civil engineer

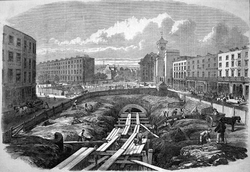

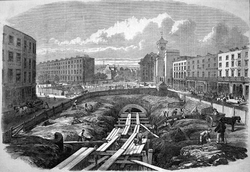

specialising in the construction of railways and railway infrastructure. In the 1850s and 1860s, he was engineer for the world's first underground railway, London's Metropolitan Railway

, built by the "cut-and-cover" method under city streets. In the 1880s, he was chief engineer for the Forth Railway Bridge, which opened in 1890. Fowler's was a long and eminent career, spanning most of the 19th century's railway expansion, and he was engineer, adviser or consultant to many British and foreign railway companies and governments. He was the youngest president of the Institution of Civil Engineers

, between 1865 and 1867, and his major works represent a lasting legacy of Victorian engineering.

, Sheffield

, Yorkshire, England, to land surveyor John Fowler and his wife Elizabeth (née Swann). He was educated privately at Whitley Hall

near Ecclesfield

. He trained under John Towlerton Leather, engineer of the Sheffield waterworks, and with Leather's uncle, George Leather, on the Aire and Calder Navigation

and on railway surveys. From 1837 he worked for John Urpeth Rastrick

on railway projects including the London and Brighton Railway

and the unbuilt West Cumberland and Furness Railway. He then worked again for George Leather as resident engineer on the Stockton and Hartlepool Railway and was appointed engineer to the railway when it opened in 1841. Fowler initially established a practice as a consulting engineer in the Yorkshire and Lincolnshire area, but, a heavy workload led him to move to London in 1844. He became a member of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers

in 1847, the year the Institution was founded, and a member of the Institution of Civil Engineers

in 1849. On 2 July 1850 he married Elizabeth Broadbent (died 1901) of Manchester. The couple had four sons.

Fowler established a busy practice, working on many railway schemes across the country. He became chief engineer for the Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway

Fowler established a busy practice, working on many railway schemes across the country. He became chief engineer for the Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway

and was engineer of the East Lincolnshire Railway

, the Oxford, Worcester and Wolverhampton Railway

and the Severn Valley Railway

. In 1853, he became chief engineer of the Metropolitan Railway

in London, the world's first underground railway. Constructed in shallow "cut-and-cover" trenches beneath roads, the line opened between Paddington and Farringdon

in 1863. Fowler was also engineer for the associated Metropolitan District Railway

and the Hammersmith and City Railway. Today these railways form the majority of the London Underground

's Circle line. For his work on the Metropolitan Railway Fowler was paid the great sum of £152,000 (£ today), with £157,000 (£ today), from the Metropolitan District Railway. Although some of this would have been passed on to staff and contractors, Sir Edward Watkin

, chairman of the Metropolitan Railway from 1872, complained that "No engineer in the world was so highly paid."

Other railways that Fowler consulted for were the London Tilbury and Southend Railway, the Great Northern Railway

, the Highland Railway

and the Cheshire Lines Railway

. Following the death of Isambard Kingdom Brunel

in 1859, Fowler was retained by the Great Western Railway

. His various appointments involved him in the design of Victoria station in London, Sheffield Victoria station, St Enoch station

in Glasgow, Liverpool Central station

and Manchester Central station

. The latter station's 210 feet (64 m) wide train shed roof was the second widest unsupported iron arch in Britain after the roof of St Pancras railway station

.

Fowler's consulting work extended beyond Britain including railway and engineering projects in Algeria, Australia, Belgium, Egypt, France, Germany, Portugal and the United States. He travelled to Egypt for the first time in 1869 and worked on a number of, mostly unrealised, schemes for the Khedive

, including a railway to Khartoum

in Sudan

which was planned in 1875 but not completed until after his death. In 1870 he provided advice to an Indian Government

inquiry on railway gauges where he recommended a narrow gauge of 3 in 6 in (1.07 m) for light railways. He visited Australia in 1886, where he made some remarks on the break of gauge difficulty. Later in his career, he was also a consultant with his partner Benjamin Baker and with James Henry Greathead

on two of London's first tube railways, the City and South London Railway and the Central London Railway

.

As part of his railway projects, Fowler designed numerous bridges. In the 1860s, he designed Grosvenor Bridge

As part of his railway projects, Fowler designed numerous bridges. In the 1860s, he designed Grosvenor Bridge

, the first railway bridge over the River Thames

, and the 13-arch Dollis Brook Viaduct

for the Edgware, Highgate and London Railway

.

He is credited with the design of the Victoria Bridge

at Upper Arley

, Worcestershire

, constructed between 1859 and 1861, and the near identical Albert Edward Bridge

at Coalbrookdale

, Shropshire

built from 1863 to 1864. Both remain in use today carrying railway lines across the River Severn

.

Following the collapse of Sir Thomas Bouch's

Tay Bridge

in 1879, Fowler, William Henry Barlow

and Thomas Elliot Harrison were appointed in 1881 to a commission to review Bouch's design for the Forth Railway Bridge. The commission recommended a steel cantilever bridge

designed by Fowler and Benjamin Baker, which was constructed between 1883 and 1890.

. The locomotive was built by Robert Stephenson and Company

and was a broad gauge

2-4-0

tender engine

. The boiler had a normal firebox connected to a large combustion chamber containing fire brick

s which were to act as a heat reservoir. The combustion chamber was linked to the smokebox

through a set of very short firetubes

. Exhaust steam was re-condensed instead of escaping and feed back to the boiler. The locomotive was intended to operate conventionally in the open, but in tunnels dampers would be closed and steam would be generated using the stored heat from the fire bricks.

The first trial on the Great Western Railway in October 1861 was a failure. The condensing system leaked, causing the boiler to run dry and pressure to drop, risking a boiler explosion. A second trial on the Metropolitan Railway in 1862 was also a failure, and the fireless engine was abandoned, becoming known as "Fowler's Ghost

". The locomotive was sold to Isaac Watt Boulton

in 1865; he intended to convert it into a standard engine but it was eventually scrapped.

On opening, the Metropolitan Railway's trains were provided by the Great Western Railway, but these were withdrawn in August 1863. After a period hiring trains from the Great Northern Railway, the Metropolitan Railway introduced its own, Fowler designed, 4-4-0

tank engines in 1864. The design, known as the A class

and, with minor updates, the B class

, was so successful that the Metropolitan and Metropolitan District Railways eventually had 120 of the engines in use and they remained in operation until electrification of the lines in the 1900s.

Fowler stood unsuccessfully for parliament as a Conservative

Fowler stood unsuccessfully for parliament as a Conservative

candidate in 1880 and 1885. His standing within the engineering profession was very high, to the extent that he was elected president of the Institution of Civil Engineers in 1865, its youngest president. Through his position in the Institution and through his own practice, he led the development of training for engineers. In 1857, he purchased a 57000 acres (23,067.1 ha) estate at Braemore

in Ross-shire

, Scotland, where he spent frequent holidays and where he was a Justice of the Peace

and a Deputy Lieutenant

of the County. He listed his recreations in Who's Who

as yachting and deerstalking and was a member of the Carlton Club

, St Stephen's Club

, the Conservative Club

and the Royal Yacht Squadron

. He was also President of the Egyptian Exploration Fund

.

In 1885 he was made a Knight Commander of the Order of Saint Michael and Saint George as thanks from the government for allowing the use of maps of the Upper Nile valley he had had made when working on the Khedive's projects. They were the most accurate survey of the area and were used in the British Relief of Khartoum. Following the successful completion of the Forth Railway Bridge in 1890, Fowler was created a baronet

, taking the name of his Scottish estate as his territorial designation

. Along with Benjamin Baker, he received an honorary degree of Doctor of Law

s from the University of Edinburgh

in 1890 for his engineering of the bridge.

Fowler died in Bournemouth

, Dorset

, at the age of 81 and is buried in Brompton Cemetery

, London. He was succeeded in the baronetcy by his son, Sir John Arthur Fowler, 2nd Baronet (died 25 March 1899). The baronetcy became extinct in 1933 on the death of Reverend Sir Montague Fowler, 4th Baronet, the first baronet's third son.

Order of St Michael and St George

The Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George is an order of chivalry founded on 28 April 1818 by George, Prince Regent, later George IV of the United Kingdom, while he was acting as Prince Regent for his father, George III....

LLD

Doctor of law

Doctor of Law or Doctor of Laws is a doctoral degree in law. The application of the term varies from country to country, and includes degrees such as the LL.D., Ph.D., J.D., J.S.D., and Dr. iur.-Argentina:...

(15 July 1817 – 20 November 1898) was an English civil engineer

Civil engineer

A civil engineer is a person who practices civil engineering; the application of planning, designing, constructing, maintaining, and operating infrastructures while protecting the public and environmental health, as well as improving existing infrastructures that have been neglected.Originally, a...

specialising in the construction of railways and railway infrastructure. In the 1850s and 1860s, he was engineer for the world's first underground railway, London's Metropolitan Railway

Metropolitan railway

Metropolitan Railway can refer to:* Metropolitan line, part of the London Underground* Metropolitan Railway, the first underground railway to be built in London...

, built by the "cut-and-cover" method under city streets. In the 1880s, he was chief engineer for the Forth Railway Bridge, which opened in 1890. Fowler's was a long and eminent career, spanning most of the 19th century's railway expansion, and he was engineer, adviser or consultant to many British and foreign railway companies and governments. He was the youngest president of the Institution of Civil Engineers

Institution of Civil Engineers

Founded on 2 January 1818, the Institution of Civil Engineers is an independent professional association, based in central London, representing civil engineering. Like its early membership, the majority of its current members are British engineers, but it also has members in more than 150...

, between 1865 and 1867, and his major works represent a lasting legacy of Victorian engineering.

Early life

Fowler was born in WadsleyWadsley

Wadsley is a suburb of the City of Sheffield in South Yorkshire, England. It stands five km NW of the city centre at an approximate grid reference of...

, Sheffield

Sheffield

Sheffield is a city and metropolitan borough of South Yorkshire, England. Its name derives from the River Sheaf, which runs through the city. Historically a part of the West Riding of Yorkshire, and with some of its southern suburbs annexed from Derbyshire, the city has grown from its largely...

, Yorkshire, England, to land surveyor John Fowler and his wife Elizabeth (née Swann). He was educated privately at Whitley Hall

Whitley Hall

Whitley Hall is a 16th century mansion which since 1969 has been converted into a restaurant and then a hotel. It is situated in the northern rural district of the City of Sheffield in South Yorkshire, England. The small hamlet of Whitley lies in the countryside between the suburbs of Grenoside,...

near Ecclesfield

Ecclesfield

Ecclesfield is a suburb and civil parish in the City of Sheffield in South Yorkshire, England, about north of Sheffield City Centre. At the 2001 census the civil parish— which also includes the Sheffield suburbs of Chapeltown, Grenoside, High Green, and formerly Thorpe Hesley —had a population...

. He trained under John Towlerton Leather, engineer of the Sheffield waterworks, and with Leather's uncle, George Leather, on the Aire and Calder Navigation

Aire and Calder Navigation

The Aire and Calder Navigation is a river and canal system of the River Aire and the River Calder in the metropolitan county of West Yorkshire, England. The first improvements to the rivers above Knottingley were completed in 1704 when the Aire was made navigable to Leeds and the Calder to...

and on railway surveys. From 1837 he worked for John Urpeth Rastrick

John Urpeth Rastrick

John Urpeth Rastrick was one of the first English steam locomotive builders. In partnership with James Foster, he formed Foster, Rastrick and Company, the locomotive construction company that built the Stourbridge Lion in 1829 for export to the Delaware and Hudson Railroad in America.-Early...

on railway projects including the London and Brighton Railway

London and Brighton Railway

The London and Brighton Railway was a railway company in England which was incorporated in 1837 and survived until 1846. Its railway runs from a junction with the London & Croydon Railway at Norwood - which gives it access from London Bridge, just south of the River Thames in central London...

and the unbuilt West Cumberland and Furness Railway. He then worked again for George Leather as resident engineer on the Stockton and Hartlepool Railway and was appointed engineer to the railway when it opened in 1841. Fowler initially established a practice as a consulting engineer in the Yorkshire and Lincolnshire area, but, a heavy workload led him to move to London in 1844. He became a member of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers

Institution of Mechanical Engineers

The Institution of Mechanical Engineers is the British engineering society based in central London, representing mechanical engineering. It is licensed by the Engineering Council UK to assess candidates for inclusion on ECUK's Register of professional Engineers...

in 1847, the year the Institution was founded, and a member of the Institution of Civil Engineers

Institution of Civil Engineers

Founded on 2 January 1818, the Institution of Civil Engineers is an independent professional association, based in central London, representing civil engineering. Like its early membership, the majority of its current members are British engineers, but it also has members in more than 150...

in 1849. On 2 July 1850 he married Elizabeth Broadbent (died 1901) of Manchester. The couple had four sons.

Railways

Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway

The Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway was formed by amalgamation in 1847. The MS&LR changed its name to the Great Central Railway in 1897 in anticipation of the opening in 1899 of its London Extension.-Origin:...

and was engineer of the East Lincolnshire Railway

East Lincolnshire Railway

The East Lincolnshire Railway was a main line railway linking the towns of Boston, Louth and Grimsby in Lincolnshire, England. It opened in 1848 and was closed to passengers in 1970.-History:...

, the Oxford, Worcester and Wolverhampton Railway

Oxford, Worcester and Wolverhampton Railway

The Oxford, Worcester and Wolverhampton railway was a company authorised on 4 August 1845 to construct a railway line from the Oxford and Rugby Railway at Wolvercot Junction to Worcester, Stourbridge, Dudley, and Wolverhampton, with a branch to the Grand Junction Railway at Bushbury...

and the Severn Valley Railway

Severn Valley Railway

The Severn Valley Railway is a heritage railway in Shropshire and Worcestershire, England. The line runs along the Severn Valley from Bridgnorth to Kidderminster, following the course of the River Severn for much of its route...

. In 1853, he became chief engineer of the Metropolitan Railway

Metropolitan railway

Metropolitan Railway can refer to:* Metropolitan line, part of the London Underground* Metropolitan Railway, the first underground railway to be built in London...

in London, the world's first underground railway. Constructed in shallow "cut-and-cover" trenches beneath roads, the line opened between Paddington and Farringdon

Farringdon station

Farringdon station is a London Underground and National Rail station in Clerkenwell, just north of the City of London in the London Borough of Islington...

in 1863. Fowler was also engineer for the associated Metropolitan District Railway

Metropolitan District Railway

The Metropolitan District Railway was the predecessor of the District line of the London Underground. Set up on 29 July 1864, at first to complete the "Inner Circle" railway around central London, it was gradually extended into the suburbs...

and the Hammersmith and City Railway. Today these railways form the majority of the London Underground

London Underground

The London Underground is a rapid transit system serving a large part of Greater London and some parts of Buckinghamshire, Hertfordshire and Essex in England...

's Circle line. For his work on the Metropolitan Railway Fowler was paid the great sum of £152,000 (£ today), with £157,000 (£ today), from the Metropolitan District Railway. Although some of this would have been passed on to staff and contractors, Sir Edward Watkin

Edward Watkin

Sir Edward William Watkin, 1st Baronet was an English railway chairman and politician.- Biography :Watkin was born in Salford, Lancashire, the son of a wealthy cotton merchant, Absalom Watkin who was noted for his involvement in the Anti-corn Law League.After a private education, he returned to...

, chairman of the Metropolitan Railway from 1872, complained that "No engineer in the world was so highly paid."

Other railways that Fowler consulted for were the London Tilbury and Southend Railway, the Great Northern Railway

Great Northern Railway (Great Britain)

The Great Northern Railway was a British railway company established by the Great Northern Railway Act of 1846. On 1 January 1923 the company lost its identity as a constituent of the newly formed London and North Eastern Railway....

, the Highland Railway

Highland Railway

The Highland Railway was one of the smaller British railways before the Railways Act 1921; it operated north of Perth railway station in Scotland and served the farthest north of Britain...

and the Cheshire Lines Railway

Cheshire Lines Committee

The Cheshire Lines Committee was the second largest joint railway in Great Britain, with 143 route miles. Despite its name, approximately 55% of its system was in Lancashire. In its publicity material it was often styled as the Cheshire Lines Railway...

. Following the death of Isambard Kingdom Brunel

Isambard Kingdom Brunel

Isambard Kingdom Brunel, FRS , was a British civil engineer who built bridges and dockyards including the construction of the first major British railway, the Great Western Railway; a series of steamships, including the first propeller-driven transatlantic steamship; and numerous important bridges...

in 1859, Fowler was retained by the Great Western Railway

Great Western Railway

The Great Western Railway was a British railway company that linked London with the south-west and west of England and most of Wales. It was founded in 1833, received its enabling Act of Parliament in 1835 and ran its first trains in 1838...

. His various appointments involved him in the design of Victoria station in London, Sheffield Victoria station, St Enoch station

St Enoch railway station

-External links:* *...

in Glasgow, Liverpool Central station

Liverpool Central railway station

Liverpool Central railway station is a railway station in Liverpool, England, and forms the central hub of the Merseyrail network, being on both the Northern Line and the Wirral Line. In the years 2008/09, Liverpool Central station was shown to be the busiest station in Liverpool, despite being...

and Manchester Central station

Manchester Central railway station

Manchester Central railway station is a former railway station in Manchester City Centre, England. One of Manchester's main railway terminals between 1880 and 1969, it now houses an exhibition and conference centre named Manchester Central.-History:...

. The latter station's 210 feet (64 m) wide train shed roof was the second widest unsupported iron arch in Britain after the roof of St Pancras railway station

St Pancras railway station

St Pancras railway station, also known as London St Pancras and since 2007 as St Pancras International, is a central London railway terminus celebrated for its Victorian architecture. The Grade I listed building stands on Euston Road in St Pancras, London Borough of Camden, between the...

.

Fowler's consulting work extended beyond Britain including railway and engineering projects in Algeria, Australia, Belgium, Egypt, France, Germany, Portugal and the United States. He travelled to Egypt for the first time in 1869 and worked on a number of, mostly unrealised, schemes for the Khedive

Isma'il Pasha

Isma'il Pasha , known as Ismail the Magnificent , was the Khedive of Egypt and Sudan from 1863 to 1879, when he was removed at the behest of the United Kingdom...

, including a railway to Khartoum

Khartoum

Khartoum is the capital and largest city of Sudan and of Khartoum State. It is located at the confluence of the White Nile flowing north from Lake Victoria, and the Blue Nile flowing west from Ethiopia. The location where the two Niles meet is known as "al-Mogran"...

in Sudan

Sudan

Sudan , officially the Republic of the Sudan , is a country in North Africa, sometimes considered part of the Middle East politically. It is bordered by Egypt to the north, the Red Sea to the northeast, Eritrea and Ethiopia to the east, South Sudan to the south, the Central African Republic to the...

which was planned in 1875 but not completed until after his death. In 1870 he provided advice to an Indian Government

British Raj

British Raj was the British rule in the Indian subcontinent between 1858 and 1947; The term can also refer to the period of dominion...

inquiry on railway gauges where he recommended a narrow gauge of 3 in 6 in (1.07 m) for light railways. He visited Australia in 1886, where he made some remarks on the break of gauge difficulty. Later in his career, he was also a consultant with his partner Benjamin Baker and with James Henry Greathead

James Henry Greathead

James Henry Greathead was an engineer renowned for his work on the London Underground railway.-Early life:Greathead was born in Grahamstown, South Africa; of English descent, Greathead's grandfather had emigrated to South Africa in 1820. He was educated at St Andrew's College, Grahamstown, and the...

on two of London's first tube railways, the City and South London Railway and the Central London Railway

Central London Railway

The Central London Railway , also known as the Twopenny Tube, was a deep-level, underground "tube" railway that opened in London in 1900...

.

Bridges

Grosvenor Bridge

Grosvenor Bridge, often alternatively called Victoria Railway Bridge, is a railway bridge over the River Thames in London, between Vauxhall Bridge and Chelsea Bridge. It actually consists of two bridges, both built in the mid-19th century...

, the first railway bridge over the River Thames

River Thames

The River Thames flows through southern England. It is the longest river entirely in England and the second longest in the United Kingdom. While it is best known because its lower reaches flow through central London, the river flows alongside several other towns and cities, including Oxford,...

, and the 13-arch Dollis Brook Viaduct

Dollis Brook Viaduct

The Dollis Brook Viaduct, also known as the Dollis Road Viaduct, Dollis Viaduct, Mill Hill Viaduct and Finchley Viaduct, is a railway viaduct in Finchley, North London, United Kingdom. It currently carries the London Underground's Northern line from Mill Hill East station to Finchley Central station...

for the Edgware, Highgate and London Railway

Edgware, Highgate and London Railway

The Edgware, Highgate and London Railway was a railway in north London. The railway was a precursor of parts of London Underground's Northern Line and was, in the 1930s the core of an ambitious expansion plan for that line which was thwarted by the Second World War...

.

He is credited with the design of the Victoria Bridge

Victoria Bridge, Worcestershire

The Victoria Bridge is a 200 ft single span railway bridge crossing the River Severn between Arley and Bewdley in Worcestershire. Opened for traffic on 31 January 1861, the original railway line was closed in 1963. The bridge now carries the operational heritage Severn Valley Railway...

at Upper Arley

Upper Arley

Upper Arley is a village is a village and civil parish near Kidderminster in the Wyre Forest District of Worcestershire, England. At the 2001 census it had a population of 645.- Amenities :...

, Worcestershire

Worcestershire

Worcestershire is a non-metropolitan county, established in antiquity, located in the West Midlands region of England. For Eurostat purposes it is a NUTS 3 region and is one of three counties that comprise the "Herefordshire, Worcestershire and Warwickshire" NUTS 2 region...

, constructed between 1859 and 1861, and the near identical Albert Edward Bridge

Albert Edward Bridge

The Albert Edward Bridge is a railway bridge spanning the River Severn at Coalbrookdale in Shropshire, England.-History:Opened on 1 November 1864, its design is almost identical to Victoria Bridge which carries the Severn Valley Railway over the Severn between Arley and Bewdley in Worcestershire...

at Coalbrookdale

Coalbrookdale

Coalbrookdale is a village in the Ironbridge Gorge in Shropshire, England, containing a settlement of great significance in the history of iron ore smelting. This is where iron ore was first smelted by Abraham Darby using easily mined "coking coal". The coal was drawn from drift mines in the sides...

, Shropshire

Shropshire

Shropshire is a county in the West Midlands region of England. For Eurostat purposes, the county is a NUTS 3 region and is one of four counties or unitary districts that comprise the "Shropshire and Staffordshire" NUTS 2 region. It borders Wales to the west...

built from 1863 to 1864. Both remain in use today carrying railway lines across the River Severn

River Severn

The River Severn is the longest river in Great Britain, at about , but the second longest on the British Isles, behind the River Shannon. It rises at an altitude of on Plynlimon, Ceredigion near Llanidloes, Powys, in the Cambrian Mountains of mid Wales...

.

Following the collapse of Sir Thomas Bouch's

Thomas Bouch

Sir Thomas Bouch was a British railway engineer in Victorian Britain.He was born in Thursby, near Carlisle, Cumberland, England and lived in Edinburgh. He helped develop the caisson and the roll-on/roll-off train ferry. He worked initially for the North British Railway and helped design parts of...

Tay Bridge

Tay Bridge disaster

The Tay Bridge disaster occurred on 28 December 1879, when the first Tay Rail Bridge, which crossed the Firth of Tay between Dundee and Wormit in Scotland, collapsed during a violent storm while a train was passing over it. The bridge was designed by the noted railway engineer Sir Thomas Bouch,...

in 1879, Fowler, William Henry Barlow

William Henry Barlow

On 28 December 1879, the central section of the North British Railway's bridge across the River Tay near Dundee collapsed in the Tay Bridge disaster as an express train crossed it in a heavy storm. All 75 passengers and crew on the train were killed...

and Thomas Elliot Harrison were appointed in 1881 to a commission to review Bouch's design for the Forth Railway Bridge. The commission recommended a steel cantilever bridge

Cantilever bridge

A cantilever bridge is a bridge built using cantilevers, structures that project horizontally into space, supported on only one end. For small footbridges, the cantilevers may be simple beams; however, large cantilever bridges designed to handle road or rail traffic use trusses built from...

designed by Fowler and Benjamin Baker, which was constructed between 1883 and 1890.

Locomotives

To avoid problems with smoke and steam overwhelming staff and passengers on the covered sections of the Metropolitan Railway, Fowler proposed a fireless locomotiveFireless locomotive

A fireless locomotive is a type of locomotive designed for use under conditions restricted by either the presence of flammable material or the need for cleanliness...

. The locomotive was built by Robert Stephenson and Company

Robert Stephenson and Company

Robert Stephenson and Company was a locomotive manufacturing company founded in 1823. It was the first company set up specifically to build railway engines.- Foundation and early success :...

and was a broad gauge

Broad gauge

Broad-gauge railways use a track gauge greater than the standard gauge of .- List :For list see: List of broad gauges, by gauge and country- History :...

2-4-0

2-4-0

Under the Whyte notation for the classification of steam locomotives, 2-4-0 represents the wheel arrangement of two leading wheels on one axle, four powered and coupled driving wheels on two axles, and no trailing wheels....

tender engine

Tender locomotive

A tender or coal-car is a special rail vehicle hauled by a steam locomotive containing the locomotive's fuel and water. Steam locomotives consume large quantities of water compared to the quantity of fuel, so tenders are necessary to keep the locomotive running over long distances. A locomotive...

. The boiler had a normal firebox connected to a large combustion chamber containing fire brick

Fire brick

A fire brick, firebrick, or refractory brick is a block of refractory ceramic material used in lining furnaces, kilns, fireboxes, and fireplaces. A refractory brick is built primarily to withstand high temperature, but will also usually have a low thermal conductivity for greater energy efficiency...

s which were to act as a heat reservoir. The combustion chamber was linked to the smokebox

Smokebox

A smokebox is one of the major basic parts of a Steam locomotive exhaust system. Smoke and hot gases pass from the firebox through tubes where they pass heat to the surrounding water in the boiler. The smoke then enters the smokebox, and is exhausted to the atmosphere through the chimney .To assist...

through a set of very short firetubes

Fire-tube boiler

A fire-tube boiler is a type of boiler in which hot gases from a fire pass through one or more tubes running through a sealed container of water...

. Exhaust steam was re-condensed instead of escaping and feed back to the boiler. The locomotive was intended to operate conventionally in the open, but in tunnels dampers would be closed and steam would be generated using the stored heat from the fire bricks.

The first trial on the Great Western Railway in October 1861 was a failure. The condensing system leaked, causing the boiler to run dry and pressure to drop, risking a boiler explosion. A second trial on the Metropolitan Railway in 1862 was also a failure, and the fireless engine was abandoned, becoming known as "Fowler's Ghost

Fowler's Ghost

"Fowler's Ghost" is the nickname given to an experimental fireless 2-4-0 steam locomotive designed by John Fowler and built in 1861 for use on the Metropolitan Railway, London's first underground railway...

". The locomotive was sold to Isaac Watt Boulton

Isaac Watt Boulton

Isaac Watt Boulton was a British engineer and founder of the locomotive-hire business known as Boulton's Siding.-Family history:...

in 1865; he intended to convert it into a standard engine but it was eventually scrapped.

On opening, the Metropolitan Railway's trains were provided by the Great Western Railway, but these were withdrawn in August 1863. After a period hiring trains from the Great Northern Railway, the Metropolitan Railway introduced its own, Fowler designed, 4-4-0

4-4-0

Under the Whyte notation for the classification of steam locomotives, 4-4-0 represents the wheel arrangement of four leading wheels on two axles , four powered and coupled driving wheels on two axles, and no trailing wheels...

tank engines in 1864. The design, known as the A class

Metropolitan Railway A Class

The Metropolitan Railway A Class were 4-4-0T steam locomotives built to work the first of the London Underground lines. They were built by Beyer, Peacock and Company from 1864....

and, with minor updates, the B class

Metropolitan Railway A Class

The Metropolitan Railway A Class were 4-4-0T steam locomotives built to work the first of the London Underground lines. They were built by Beyer, Peacock and Company from 1864....

, was so successful that the Metropolitan and Metropolitan District Railways eventually had 120 of the engines in use and they remained in operation until electrification of the lines in the 1900s.

Other activities and professional recognition

Conservative Party (UK)

The Conservative Party, formally the Conservative and Unionist Party, is a centre-right political party in the United Kingdom that adheres to the philosophies of conservatism and British unionism. It is the largest political party in the UK, and is currently the largest single party in the House...

candidate in 1880 and 1885. His standing within the engineering profession was very high, to the extent that he was elected president of the Institution of Civil Engineers in 1865, its youngest president. Through his position in the Institution and through his own practice, he led the development of training for engineers. In 1857, he purchased a 57000 acres (23,067.1 ha) estate at Braemore

Braemore

Braemore is a settlement in Berriedale in the Highland council area of Scotland....

in Ross-shire

Ross-shire

Ross-shire is an area in the Highland Council Area in Scotland. The name is now used as a geographic or cultural term, equivalent to Ross. Until 1889 the term denoted a county of Scotland, also known as the County of Ross...

, Scotland, where he spent frequent holidays and where he was a Justice of the Peace

Justice of the Peace

A justice of the peace is a puisne judicial officer elected or appointed by means of a commission to keep the peace. Depending on the jurisdiction, they might dispense summary justice or merely deal with local administrative applications in common law jurisdictions...

and a Deputy Lieutenant

Deputy Lieutenant

In the United Kingdom, a Deputy Lieutenant is one of several deputies to the Lord Lieutenant of a lieutenancy area; an English ceremonial county, Welsh preserved county, Scottish lieutenancy area, or Northern Irish county borough or county....

of the County. He listed his recreations in Who's Who

Who's Who

Who's Who is the title of a number of reference publications, generally containing concise biographical information on a particular group of people...

as yachting and deerstalking and was a member of the Carlton Club

Carlton Club

The Carlton Club is a gentlemen's club in London which describes itself as the "oldest, most elite, and most important of all Conservative clubs." Membership of the club is by nomination and election only.-History:...

, St Stephen's Club

St Stephen's Club

St Stephen's Club is a private member's club in Westminster, founded in 1870.St Stephen's was originally on the corner of Bridge Street and the Embankment, in London SW1, which the government building Portcullis House now occupies....

, the Conservative Club

Conservative Club

The Conservative Club was a London gentlemen's club, now dissolved, which was established in 1840. In 1950 it merged with the Bath Club, and was disbanded in 1981...

and the Royal Yacht Squadron

Royal Yacht Squadron

The Royal Yacht Squadron is the most prestigious yacht club in the United Kingdom and arguably the world. Its clubhouse is located in Cowes Castle on the Isle of Wight in the United Kingdom...

. He was also President of the Egyptian Exploration Fund

Egypt Exploration Society

The Egypt Exploration Society is the foremost learned society in the United Kingdom promoting the field of Egyptology....

.

In 1885 he was made a Knight Commander of the Order of Saint Michael and Saint George as thanks from the government for allowing the use of maps of the Upper Nile valley he had had made when working on the Khedive's projects. They were the most accurate survey of the area and were used in the British Relief of Khartoum. Following the successful completion of the Forth Railway Bridge in 1890, Fowler was created a baronet

Baronet

A baronet or the rare female equivalent, a baronetess , is the holder of a hereditary baronetcy awarded by the British Crown...

, taking the name of his Scottish estate as his territorial designation

Territorial designation

A territorial designation follows modern peerage titles, linking them to a specific place or places. It is also an integral part of all baronetcies...

. Along with Benjamin Baker, he received an honorary degree of Doctor of Law

Doctor of law

Doctor of Law or Doctor of Laws is a doctoral degree in law. The application of the term varies from country to country, and includes degrees such as the LL.D., Ph.D., J.D., J.S.D., and Dr. iur.-Argentina:...

s from the University of Edinburgh

University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh, founded in 1583, is a public research university located in Edinburgh, the capital of Scotland, and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The university is deeply embedded in the fabric of the city, with many of the buildings in the historic Old Town belonging to the university...

in 1890 for his engineering of the bridge.

Fowler died in Bournemouth

Bournemouth

Bournemouth is a large coastal resort town in the ceremonial county of Dorset, England. According to the 2001 Census the town has a population of 163,444, making it the largest settlement in Dorset. It is also the largest settlement between Southampton and Plymouth...

, Dorset

Dorset

Dorset , is a county in South West England on the English Channel coast. The county town is Dorchester which is situated in the south. The Hampshire towns of Bournemouth and Christchurch joined the county with the reorganisation of local government in 1974...

, at the age of 81 and is buried in Brompton Cemetery

Brompton Cemetery

Brompton Cemetery is located near Earl's Court in South West London, England . It is managed by The Royal Parks and is one of the Magnificent Seven...

, London. He was succeeded in the baronetcy by his son, Sir John Arthur Fowler, 2nd Baronet (died 25 March 1899). The baronetcy became extinct in 1933 on the death of Reverend Sir Montague Fowler, 4th Baronet, the first baronet's third son.