History of women's suffrage in the United States

Encyclopedia

Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution prohibits any United States citizen to be denied the right to vote based on sex. It was ratified on August 18, 1920....

, which provided: "The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex."

The Seneca Falls Convention

Seneca Falls Convention

The Seneca Falls Convention was an early and influential women's rights convention held in Seneca Falls, New York, July 19–20, 1848. It was organized by local New York women upon the occasion of a visit by Boston-based Lucretia Mott, a Quaker famous for her speaking ability, a skill rarely...

of 1848 formulated the demand for women's suffrage

Women's suffrage

Women's suffrage or woman suffrage is the right of women to vote and to run for office. The expression is also used for the economic and political reform movement aimed at extending these rights to women and without any restrictions or qualifications such as property ownership, payment of tax, or...

in the United States of America and after the American Civil War

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

(1861–1865) agitation for the cause became more prominent. In 1869 the proposed Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution prohibits each government in the United States from denying a citizen the right to vote based on that citizen's "race, color, or previous condition of servitude"...

, which gave the vote to black men, caused controversy as women's suffrage campaigners such as Susan B. Anthony

Susan B. Anthony

Susan Brownell Anthony was a prominent American civil rights leader who played a pivotal role in the 19th century women's rights movement to introduce women's suffrage into the United States. She was co-founder of the first Women's Temperance Movement with Elizabeth Cady Stanton as President...

and Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Elizabeth Cady Stanton was an American social activist, abolitionist, and leading figure of the early woman's movement...

refused to endorse the amendment, as it did not give the vote to women. Others, such as Lucy Stone

Lucy Stone

Lucy Stone was a prominent American abolitionist and suffragist, and a vocal advocate and organizer promoting rights for women. In 1847, Stone was the first woman from Massachusetts to earn a college degree. She spoke out for women's rights and against slavery at a time when women were discouraged...

and Julia Ward Howe

Julia Ward Howe

Julia Ward Howe was a prominent American abolitionist, social activist, and poet, most famous as the author of "The Battle Hymn of the Republic".-Biography:...

however argued that if black men were enfranchised, women would achieve their goal. The conflict caused two organisations to emerge, the National Woman Suffrage Association, which campaigned for women's suffrage at a federal level as well as for married women to be given property rights, and the American Woman Suffrage Association, which aimed to secure women's suffrage through state legislation.

Beginnings

Lydia TaftLydia Taft

Lydia Chapin was the first known legal woman voter in colonial America. This occurred in the New England town Town Meeting, at Uxbridge, MA Massachusetts Colony.-Early life:...

(1712 – 1778), a wealthy widow, was allowed to vote in town meetings in Uxbridge, Massachusetts

Uxbridge, Massachusetts

Uxbridge is a town in Worcester County, Massachusetts, in the United States. It was first settled in 1662, incorporated in 1727 at Suffolk County, and named for the Earl of Uxbridge. Uxbridge is south-southeast of Worcester, north-northwest of Providence, and southwest of Boston. It is part of...

in 1756. No other women in the colonial era are known to have had the right to vote.

New Jersey

New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Northeastern and Middle Atlantic regions of the United States. , its population was 8,791,894. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York, on the southeast and south by the Atlantic Ocean, on the west by Pennsylvania and on the southwest by Delaware...

in 1776 placed only one restriction on the general suffrage, which was the possession of at least £50 in cash or property (about $ adjusted for inflation), with the election laws referring to the voters as “he or she.” In 1790, the law was revised to specifically include women, but in 1807 the law was again revised to exclude them, an unconstitutional act since the state constitution specifically made any such change dependent on the general suffrage.

During the early part of the 19th century, agitation for equal suffrage was carried on by only a few individuals. The first of these was Frances Wright

Frances Wright

Frances Wright also widely known as Fanny Wright, was a Scottish-born lecturer, writer, freethinker, feminist, abolitionist, and social reformer, who became a U. S. citizen in 1825...

, a Scottish

Scottish American

Scottish Americans or Scots Americans are citizens of the United States whose ancestry originates wholly or partly in Scotland. Scottish Americans are closely related to Scots-Irish Americans, descendants of Ulster Scots, and communities emphasize and celebrate a common heritage...

woman who came to the country in 1826 and advocated women's suffrage in an extensive series of lectures. In 1836 Ernestine Rose

Ernestine Rose

Ernestine Louise Rose was an atheist feminist, Individualist Feminist, and abolitionist. She was one of the major intellectual forces behind the women's rights movement in nineteenth-century America....

, a Polish

Polish American

A Polish American , is a citizen of the United States of Polish descent. There are an estimated 10 million Polish Americans, representing about 3.2% of the population of the United States...

woman, came to the country and carried on a similar campaign so effectively that she obtained a personal hearing before the New York

New York

New York is a state in the Northeastern region of the United States. It is the nation's third most populous state. New York is bordered by New Jersey and Pennsylvania to the south, and by Connecticut, Massachusetts and Vermont to the east...

Legislature, though her petition bore only five signatures. At about the same time, in 1840, Lucretia Mott

Lucretia Mott

Lucretia Coffin Mott was an American Quaker, abolitionist, social reformer, and proponent of women's rights.- Early life and education:...

and Margaret Fuller

Margaret Fuller

Sarah Margaret Fuller Ossoli, commonly known as Margaret Fuller, was an American journalist, critic, and women's rights advocate associated with the American transcendentalism movement. She was the first full-time American female book reviewer in journalism...

became active in Boston, the latter being the author of the book The Great Lawsuit; Man vs. Woman.

1848

Rochester, New York

Rochester is a city in Monroe County, New York, south of Lake Ontario in the United States. Known as The World's Image Centre, it was also once known as The Flour City, and more recently as The Flower City...

, Gerrit Smith

Gerrit Smith

Gerrit Smith was a leading United States social reformer, abolitionist, politician, and philanthropist...

was nominated as the Liberty Party

Liberty Party (1840s)

The Liberty Party was a minor political party in the United States in the 1840s . The party was an early advocate of the abolitionist cause...

's presidential candidate. Smith was Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Elizabeth Cady Stanton was an American social activist, abolitionist, and leading figure of the early woman's movement...

's first cousin, and the two enjoyed debating and discussing political and social issues with each other whenever he came to visit. At the National Liberty Convention, held June 14–15 in Buffalo, New York

Buffalo, New York

Buffalo is the second most populous city in the state of New York, after New York City. Located in Western New York on the eastern shores of Lake Erie and at the head of the Niagara River across from Fort Erie, Ontario, Buffalo is the seat of Erie County and the principal city of the...

, Smith gave a major address, including in his speech a demand for "universal suffrage in its broadest sense, females as well as males being entitled to vote." The delegates approved a passage in their party platform

Party platform

A party platform, or platform sometimes also referred to as a manifesto, is a list of the actions which a political party, individual candidate, or other organization supports in order to appeal to the general public for the purpose of having said peoples' candidates voted into political office or...

addressing votes for women: "Neither here, nor in any other part of the world, is the right of suffrage allowed to extend beyond one of the sexes. This universal exclusion of woman... argues, conclusively, that, not as yet, is there one nation so far emerged from barbarism, and so far practically Christian, as to permit woman to rise up to the one level of the human family." At this convention, five votes were placed calling for Lucretia Mott to be Smith's vice-president—the first time in the United States that a woman was nominated for federal executive office.

On July 19–20, 1848, in upstate New York

Upstate New York

Upstate New York is the region of the U.S. state of New York that is located north of the core of the New York metropolitan area.-Definition:There is no clear or official boundary between Upstate New York and Downstate New York...

, the Seneca Falls Convention

Seneca Falls Convention

The Seneca Falls Convention was an early and influential women's rights convention held in Seneca Falls, New York, July 19–20, 1848. It was organized by local New York women upon the occasion of a visit by Boston-based Lucretia Mott, a Quaker famous for her speaking ability, a skill rarely...

on women's rights was hosted by Lucretia Mott, Mary Ann M'Clintock and Elizabeth Cady Stanton; some 300 attended including Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass was an American social reformer, orator, writer and statesman. After escaping from slavery, he became a leader of the abolitionist movement, gaining note for his dazzling oratory and incisive antislavery writing...

, who stood up to speak in favor of women's suffrage to settle an inconclusive debate on the subject.

The early years

Lucy StoneLucy Stone

Lucy Stone was a prominent American abolitionist and suffragist, and a vocal advocate and organizer promoting rights for women. In 1847, Stone was the first woman from Massachusetts to earn a college degree. She spoke out for women's rights and against slavery at a time when women were discouraged...

met with Paulina Kellogg Wright Davis

Paulina Kellogg Wright Davis

Paulina Kellogg Wright Davis was an American abolitionist, suffragist, and educator.Paulina Kellogg was born in Bloomfield, New York, to Captain Ebenezer Kellogg and Polly Saxton. The family moved to the frontier near Niagara Falls in 1817...

, Abby Kelley Foster

Abby Kelley

Abby Kelley Foster was an American abolitionist and radical social reformer active from the 1830s to 1870s. She became a fundraiser, lecturer and committee organizer for the influential American Anti-Slavery Society, where she worked closely with William Lloyd Garrison and other radicals...

, William Lloyd Garrison

William Lloyd Garrison

William Lloyd Garrison was a prominent American abolitionist, journalist, and social reformer. He is best known as the editor of the abolitionist newspaper The Liberator, and as one of the founders of the American Anti-Slavery Society, he promoted "immediate emancipation" of slaves in the United...

, Wendell Phillips

Wendell Phillips

Wendell Phillips was an American abolitionist, advocate for Native Americans, and orator. He was an exceptional orator and agitator, advocate and lawyer, writer and debater.-Education:...

and six other women to organize the larger National Women's Rights Convention

National Women's Rights Convention

The National Women's Rights Convention was an annual series of meetings that increased the visibility of the early women's rights movement in the United States. First held in 1850 in Worcester, Massachusetts, the National Women's Rights Convention combined both male and female leadership, and...

in 1850. This national convention brought together for the first time many of those who had been working individually for women's rights. While conventions provided places where women could support each other, they also highlighted some of the challenges of unifying strongly opinionated leaders into one movement. Women's rights activists faced difficult questions. Should the movement include or exclude men? Who was to blame for women's inequality? What remedies should they seek? How could women best convince others of their need for equality? One goal, however, was clear. Attendees resolved to "secure for [woman] political, legal and social equality with man," giving her the opportunity to freely choose her sphere. On the closing day, Stone gave a stirring speech to the thousand-strong audience, one which inspired Susan B. Anthony

Susan B. Anthony

Susan Brownell Anthony was a prominent American civil rights leader who played a pivotal role in the 19th century women's rights movement to introduce women's suffrage into the United States. She was co-founder of the first Women's Temperance Movement with Elizabeth Cady Stanton as President...

to join the cause.

Women's rights advocates held national conventions every year but one until the onset of the Civil War.

Some future leaders got their start at these meetings. Twenty-six-year-old Matilda Joslyn Gage

Matilda Joslyn Gage

Matilda Electa Joslyn Gage was a suffragist, a Native American activist, an abolitionist, a freethinker, and a prolific author, who was "born with a hatred of oppression".-Early activities:...

, one of the eventual leaders of the movement, presented her first speech at the 1852 meeting. She spoke so timidly that few could hear. Others had been honing their skills in the temperance (anti-alcohol) and abolitionist movements for years. Abby Kelley Foster boldly stated, "For fourteen years I have advocated this cause in my daily life. Bloody feet, sisters, have worn smooth the path by which you have come hither." Abolitionist and ex-slave Sojourner Truth

Sojourner Truth

Sojourner Truth was the self-given name, from 1843 onward, of Isabella Baumfree, an African-American abolitionist and women's rights activist. Truth was born into slavery in Swartekill, New York, but escaped with her infant daughter to freedom in 1826. After going to court to recover her son, she...

commanded attention at a regional meeting at Akron, Ohio

Akron, Ohio

Akron , is the fifth largest city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Summit County. It is located in the Great Lakes region approximately south of Lake Erie along the Little Cuyahoga River. As of the 2010 census, the city had a population of 199,110. The Akron Metropolitan...

in 1851, challenging the notion that equality was only for white, educated men and women. When she rose to her nearly six-foot stature and gave an oration that became known as the "Ain't I a Woman?" speech, she left her audience with faces "beaming with joyous gladness".

Elizabeth Cady Stanton was conspicuously missing from most of these early conventions. Following an active fall of 1848, Stanton felt her family pulling her inward. Neither her father nor her husband supported her women's rights work, and her family continued to grow and demand her attention. While others, such as Lucy Stone

Lucy Stone

Lucy Stone was a prominent American abolitionist and suffragist, and a vocal advocate and organizer promoting rights for women. In 1847, Stone was the first woman from Massachusetts to earn a college degree. She spoke out for women's rights and against slavery at a time when women were discouraged...

, kept up a grueling pace lecturing and organizing conferences, Stanton was "surrounded" by her "children, washing dishes, baking, sewing, etc." On the side, she wrote letters to the editor and articles under the name of Sunflower.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton's strong opinions didn't always make her popular. One young woman from Seneca Falls refused to ride in the same carriage, saying, "I wouldn't have been seen with her for anything, with those ideas of hers." In 1851, she met 31-year-old Susan B. Anthony who, stung by discrimination against women in the temperance movement, gradually diverted her considerable energy to the cause of women's rights. Anthony emerged as a gifted organizer—Stanton, a sharp thinker. Together, they became a formidable partnership that would last until Stanton's writing of The Woman's Bible

The Woman's Bible

The Woman's Bible is a two-part book, written by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and a committee of 26 women, and published in 1895 and 1898 to challenge the traditional position of religious orthodoxy that woman should be subservient to man. By producing the book, Stanton wished to promote a radical...

, a controversial work that alienated many suffrage activists in 1896.

Susan Anthony assumed leadership of the women's rights movement. Eventually, she became the only leader remembered in history books; her image was used to inspire a new generation of feminists in the 1970s.

By 1860, women's rights advocates had made some headway. In Indiana, divorces could be granted on the basis not only of adultery, but on desertion, drunkenness, and cruelty. In New York, Indiana, Maine, Missouri, and Ohio, women's property rights had expanded to allow married women to keep their own wages. Clearly there was still much to be done. However, reformers had given a name to women's oppression and had set into motion the movement that would continue to change American attitudes for years to come, as they pushed for reform in everything from education to underwear.

Access to divorce depended upon in which American state a person lived, and upon the woman's legal resources. Some states opposed divorce on almost all grounds. After her husband horsewhipped and beat her, one woman took her plea for divorce to the North Carolina Supreme Court in 1862. The Chief Justice denied her, stating, "The law gives the husband power to use such a degree of force necessary to make the wife behave and know her place."

Civil War

During the Civil WarAmerican Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

, and immediately thereafter, little was heard of the movement, but a strong drive for woman suffrage was mounted in Kansas

Kansas

Kansas is a US state located in the Midwestern United States. It is named after the Kansas River which flows through it, which in turn was named after the Kansa Native American tribe, which inhabited the area. The tribe's name is often said to mean "people of the wind" or "people of the south...

in 1866–1867. After this effort failed, strategic differences among suffragists came to a head. Anthony and Stanton began publishing The Revolution

The Revolution (newspaper)

The Revolution was a weekly women's rights newspaper published between January 8, 1868 and February 1872. It was the official publication of the National Woman Suffrage Association which was formed by feminists Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony...

in January 1868, writing harsh criticisms of the Republican party which was then pushing for African-American male suffrage. In November 1868, in Boston at the largest women's rights convention held to that date in the U.S., Stone, her husband Henry Browne Blackwell, Isabella Beecher Hooker

Isabella Beecher Hooker

Isabella Beecher Hooker was a leader in the women's suffrage movement and an author.-Biography:Born in Litchfield, Connecticut, she was a daughter of Reverend Lyman Beecher, a noted abolitionist. Among her half brothers and sisters were Henry Ward Beecher, Charles Beecher, Catharine Beecher, and...

, Julia Ward Howe

Julia Ward Howe

Julia Ward Howe was a prominent American abolitionist, social activist, and poet, most famous as the author of "The Battle Hymn of the Republic".-Biography:...

and Thomas Wentworth Higginson

Thomas Wentworth Higginson

Thomas Wentworth Higginson was an American Unitarian minister, author, abolitionist, and soldier. He was active in the American Abolitionism movement during the 1840s and 1850s, identifying himself with disunion and militant abolitionism...

formed a new organization, the New England Woman Suffrage Association (NEWSA); the first major political society established for the sole purpose of gaining suffrage for women. It was a pro-Republican group, with men in important leadership positions, designed to attract an alliance with that political party. However, the Republican connection pushed the group in the direction of advocating voting rights for the African-American male. At the first NEWSA convention, Douglass declared that "the cause of the negro was more pressing than that of woman's." In May 1869, the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) was formed by Susan B. Anthony

Susan B. Anthony

Susan Brownell Anthony was a prominent American civil rights leader who played a pivotal role in the 19th century women's rights movement to introduce women's suffrage into the United States. She was co-founder of the first Women's Temperance Movement with Elizabeth Cady Stanton as President...

and Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Elizabeth Cady Stanton was an American social activist, abolitionist, and leading figure of the early woman's movement...

; an organization made up primarily of women. Their object was to secure an amendment to the Constitution

United States Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the supreme law of the United States of America. It is the framework for the organization of the United States government and for the relationship of the federal government with the states, citizens, and all people within the United States.The first three...

in favor of women's suffrage, and they opposed passage of the Fifteenth Amendment

Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution prohibits each government in the United States from denying a citizen the right to vote based on that citizen's "race, color, or previous condition of servitude"...

("The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude") unless it was changed to guarantee to women the right to vote. They continued work on The Revolution which included radical feminist challenges to traditional female roles.

Later the same year, Stone reorganized NEWSA into the much larger and more moderate American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA) which also included both men and women in its membership. AWSA supported the proposed Fifteenth Amendment as written, and resolved to gain the incremental victory of black men's voting rights before moving forward to achieve women's voting rights. After the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment, AWSA continued working at the state level to secure women's voting rights. NWSA proposed a Sixteenth Amendment, one which would give women the right to vote. Their efforts were unsuccessful; many could not forgive Anthony and Stanton the racism they demonstrated during the fight for the Fifteenth.

In 1887 after 20 years of working in parallel toward the same goals but with bitter resentment between the various leaders, Stone called for a merger of the splintered women's rights organizations, and plans were drawn up for approval. In 1890, the two groups united to form one national organization known as the National American Woman Suffrage Association

National American Woman Suffrage Association

The National American Woman Suffrage Association was an American women's rights organization formed in May 1890 as a unification of the National Woman Suffrage Association and the American Woman Suffrage Association...

(NAWSA).

Drinking men typically opposed women's suffrage for fear that women would use their vote to enact prohibition of alcoholic beverages

Prohibition

Prohibition of alcohol, often referred to simply as prohibition, is the practice of prohibiting the manufacture, transportation, import, export, sale, and consumption of alcohol and alcoholic beverages. The term can also apply to the periods in the histories of the countries during which the...

. Indeed the WCTU was a main force for suffrage as well as prohibition At the time, "temperance

Temperance movement

A temperance movement is a social movement urging reduced use of alcoholic beverages. Temperance movements may criticize excessive alcohol use, promote complete abstinence , or pressure the government to enact anti-alcohol legislation or complete prohibition of alcohol.-Temperance movement by...

" was frequently seen as a women's issue, and the liquor-saloon financed the opposition.

National American Woman Suffrage Association

The 1887 merger reinvigorated the movement, led until 1894 by Susan B. Anthony. The merger marginalized of radical voices, and ensured broad support for a national agenda to bring the 19th Amendment to a vote in Congress.In 1900, regular national headquarters were established in New York City, under the direction of the new president, Carrie Chapman Catt

Carrie Chapman Catt

Carrie Chapman Catt was a women's suffrage leader who campaigned for the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution which gave U.S. women the right to vote in 1920...

, who was endorsed by Susan B. Anthony after her retirement as president. Three years later headquarters were moved to Warren, Ohio

Warren, Ohio

As of the census of 2000, there were 46,832 people, 19,288 households and 12,035 families residing in the city. The population density was 2,912.4 people per square mile . There were 21,279 housing units at an average density of 1,322.9 per square mile...

, but were then brought back to New York again shortly afterward, and re-opened there on a much larger scale. The organization obtained a hearing before every Congress, from 1869 to 1919.

Ethnicity and Suffrage

The woman suffrage movement was led by old stock women, especially Yankees and Quakers of English or German ancestry, whose families had been in North America for generations. There were important ethnic involvements as well by recent immigrants. Norwegian AmericanNorwegian American

Norwegian Americans are Americans of Norwegian descent. Norwegian immigrants went to the United States primarily in the later half of the 19th century and the first few decades of the 20th century. There are more than 4.5 million Norwegian Americans according to the most recent U.S. census, and...

women, based in the rural upper Midwest, built their claims to an American identity on their suffrage work. They felt that the progressive politics of Norway, which included women's rights, provided a strong foundation for their demands for political equality and inclusion in the U.S. They told their kinswomen they had a cultural duty to promote women's rights, especially through the Scandinavian Woman's Suffrage Association.

Female muscular prowess

In an age when many Protestant denominations were promoting "muscular Christianity" with a stress on social activism as part of the Social GospelSocial Gospel

The Social Gospel movement is a Protestant Christian intellectual movement that was most prominent in the early 20th century United States and Canada...

, the suffragists became involved as well.

Schultz argues that suffragists promoted swimming competitions, scaled mountains, piloted aeroplanes and staged large-scale parades to gain publicity and emphasize their new physical activism. In a sense, they spectacularized suffrage by thrusting their bodies in the public sphere rather than remaining behind closed doors. In New York in 1912 they organized a 12-day, 170-mile "Hike to Albany'. In 1913 the suffragist "Army of the Hudson" marched the 225 miles from Newark to Washington in 16 days, with numerous photo opportunities and press availabilities along the way that gained a national audience. The Woman Voter magazine claimed the hikes generated $3 million worth of free publicity. The women, says Schultz, "staked a symbolic claim on the polity," as they contrasted their democratic rights to assemble and speak freely with the denial of full citizenship in terms of voting. Simultaneously they undermined the myths of women's physical and political inferiority.

The monthly women's magazine The Delineator, in the 1890s to the 1920s was edited by Charles Dwyer, Theodore Dreiser

Theodore Dreiser

Theodore Herman Albert Dreiser was an American novelist and journalist of the naturalist school. His novels often featured main characters who succeeded at their objectives despite a lack of a firm moral code, and literary situations that more closely resemble studies of nature than tales of...

and William Hard. They emphasized the "New Woman" who enjoyed sports such as golf, archery, and gymnastics, appreciated new technologies such as automobiles, and embraced social reform.

Fighting prostitution

Suffrage activists, especially Harriet Burton Laidlaw and Rose Livingston, worked in the Chinatown section of New York and in other cities to rescue young white and Chinese girls from forced prostitution, and helped pass the Mann ActMann Act

The White-Slave Traffic Act, better known as the Mann Act, is a United States law, passed June 25, 1910 . It is named after Congressman James Robert Mann, and in its original form prohibited white slavery and the interstate transport of females for “immoral purposes”...

of 1910 that made interstate sex trafficking a federal crime.

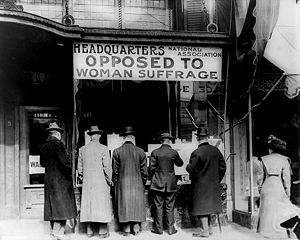

Opposition

The opposition to women's suffrage in the United States included organizations like the National Organization Against Women's Suffrage and women like Helen Kendrick JohnsonHelen Kendrick Johnson

Helen Kendrick Johnson was an American writer, poet, and prominent activist opposing the women's suffrage movement.- Early life :...

. In New York, upper class women who thought they had a behind-the-scenes voice often opposed suffrage because it would dilute their influence. At first the anti-s let the men do the talking, but increasingly they adopted the mobilization techniques pioneered by the suffragists. The antis easily won the 1915 New York State referendum, using the argument that women voters would close the saloons. But the suffragists won the 1917 referendum, arguing that the saloons were Germanic (at a time when Germany was hated); the Tammany Hall machine in New York City deserted the antis as well. Nationwide, male voters made the decision and the opposition was led by Southern white men (afraid that black women would vote), ethnic politicians (especially Catholics whose women were not allowed a political voice) and the liquor forces (who realized correctly that most women would vote dry.)

National Woman's Party

The National Woman's PartyNational Woman's Party

The National Woman's Party , was a women's organization founded by Alice Paul in 1915 that fought for women's rights during the early 20th century in the United States, particularly for the right to vote on the same terms as men...

(NWP), was a women's organization founded in 1917 that fought for women's rights during the early 20th century in the United States, particularly for the right to vote on the same terms as men. In contrast to other organizations, such as the National American Woman Suffrage Association, which focused on lobbying individual states and from which the NWP split, the NWP put its priority on the passage of a constitutional amendment ensuring women's suffrage. Alice Paul

Alice Paul

Alice Stokes Paul was an American suffragist and activist. Along with Lucy Burns and others, she led a successful campaign for women's suffrage that resulted in the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1920.-Activism: Alice Paul received her undergraduate education from...

and Lucy Burns

Lucy Burns

Lucy Burns was an American suffragist and women's rights advocate. She was a passionate activist in the United States and in the United Kingdom. Burns was a close friend of Alice Paul, and together they ultimately formed the National Woman's Party.-Early life and education:Lucy Burns was born in...

founded the organization originally under the name the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage in 1913; by 1917, the name had been changed to the National Women's Party, during which time Alva Belmont

Alva Belmont

Alva Erskine Belmont , née Alva Erskine Smith, also called Alva Vanderbilt from 1875 to 1896, was a prominent multi-millionaire American socialite and a major figure in the women's suffrage movement...

was appointed President. She held the oath until her death (1933).

World War I

World War I provided the final push for women's suffrage in America. After President Woodrow Wilson announced that World War I was a war for democracy, women were up in arms. Members of the NWP held up banners saying that the United States was not a democracy. Women in the audience of his public speeches began to ask the question "Mr. President, if you sincerely desire to forward the interests of all the people, why do you oppose the national enfranchisement of women?" On January 1918 the President acceded to the women who had been protesting at his public speeches and made a pro-suffrage speech. The next year Congress passed the Nineteenth Amendment

Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution prohibits any United States citizen to be denied the right to vote based on sex. It was ratified on August 18, 1920....

giving women the right to vote.

Internal divisions

Another problem for the Equal Rights Association was funding. It took good deal of money to rent halls for speeches, print pamphlets, and pay suffrage workers. Most of the contributors, however, were female volunteers without incomes. The campaign of 1867 was the very first test of women's suffrage; and most activists were not experienced in raising money. Even more frustrating, as Susan B. Anthony expressed in a letter to Sam Wood, "neither the radical republicans or Old Abolitionists, nor yet the Democrats open their purses, pulpits or presses to our movement."These conflicts eroded the loyalties between abolitionists and feminists in the Equal Rights Association until its near-disintegration in the summer of 1867. The major eruption, however, stemmed from the schism created within the women's suffrage movement itself. Stone and Blackwell, who had worked closely with Stanton and Anthony throughout the campaign, were appalled by the decision to collaborate with the overtly racist Train. Stanton's and Anthony's steadfast commitment to Train left them vulnerable to the Republican accusation that the Democratic party was only using women's suffrage to defeat black suffrage, thus giving black equal rights supporters reason to feel animosity towards suffragists. In The Revolution, Anthony wrote that 2 million black men, among "the lowest orders of manhood", were inferior to 15 million white women, a racist position which shocked her former allies. The final blow to the Equal Rights Association came during the annual meeting in May 1869. Stanton and Anthony found themselves outnumbered by the majority of women suffrage activists, accused of racism and opposing the Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution prohibits each government in the United States from denying a citizen the right to vote based on that citizen's "race, color, or previous condition of servitude"...

. Realizing that they could not win, the two women withdrew from the Equal Rights Association. Two days later, they formed their own separate association.

Woman suffrage in individual states

Victoria Woodhull

Victoria Claflin Woodhull was an American leader of the woman's suffrage movement, an advocate of free love; together with her sister, the first women to operate a brokerage in Wall Street; the first women to start a weekly newspaper; an activist for women's rights and labor reforms and, in 1872,...

in 1872, and Belva Lockwood in 1884 and 1888. Neither was permitted under the law to vote, but nothing in the law prevented them from running for office. Each woman pointed to this irony in her campaigning. Lockwood ran a fuller, more national campaign than Woodhull, giving speeches across the country and organizing several electoral tickets.

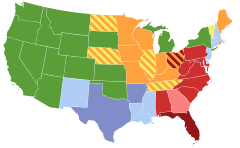

West

On the whole, western states and territories were more favorable to women's suffrage than eastern ones (see map). It has been suggested that western areas, faced with a shortage of women on the frontier, "sweetened the deal" in order to make themselves more attractive to women so as to encourage female immigration or that they gave the vote as a reward to those women already there. Susan Anthony said that western men were more chivalrous than their eastern brethren. 1871 Anthony and Stanton toured several western states, with special attention to the territories of Wyoming and Utah where women already had equal suffrage. Their feminist speeches were often ridiculed or denounced by the opinion makers - the politicians, ministers, and editors. Anthony returned to the West in 1877, 1895, and 1896. By the last trip, at age 76, Anthony's views had gained popularity and respect. Activists concentrated on the single issue of suffrage and went directly to the opinion makers to educate them and to persuade them to support the goal of suffrage.By 1920 when women got the vote nationwide, Wyoming women had already been voting for half a century.

Kansas

In the summer of 1865, Republicans proposed a Fourteenth Amendment to the United States ConstitutionFourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution was adopted on July 9, 1868, as one of the Reconstruction Amendments.Its Citizenship Clause provides a broad definition of citizenship that overruled the Dred Scott v...

that would enfranchise the two million newly freed black men. This was the first time the word "male" would be introduced into the Constitution, and women were now explicitly not guaranteed the right to vote. Thus, feminists, in an effort to secure their political rights alongside freedmen, resolved to combine the abolitionist and suffragist movements into one Equal Rights Association, an idea officially proposed by female suffrage

Suffrage

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply the franchise, distinct from mere voting rights, is the civil right to vote gained through the democratic process...

activists Lucy Stone

Lucy Stone

Lucy Stone was a prominent American abolitionist and suffragist, and a vocal advocate and organizer promoting rights for women. In 1847, Stone was the first woman from Massachusetts to earn a college degree. She spoke out for women's rights and against slavery at a time when women were discouraged...

and Susan B. Anthony

Susan B. Anthony

Susan Brownell Anthony was a prominent American civil rights leader who played a pivotal role in the 19th century women's rights movement to introduce women's suffrage into the United States. She was co-founder of the first Women's Temperance Movement with Elizabeth Cady Stanton as President...

at an antislavery meeting in January, 1866. The suffragists believed they had support for the proposal from the abolitionists, who had previously supported their cause. However, when the Republican Party chose to make black suffrage part of their program during Reconstruction the Republicans began to collaborate more closely with the abolitionists, and by 1867, most were full supporters of the Republican Party. The Republican party believed that black suffrage, which was a party measure in national politics held far more prospects than women's suffrage, and the Republican cry was "this is the negro's hour."

After the defeat in New York in 1867, Sam Wood, leader of a rebel faction of the state Republican Party, arrived in Kansas by request of Stone, and invited the Equal Rights Association to help launch their women's suffrage campaign. Wood had emigrated to Kansas to prevent the extension of slavery

Slavery

Slavery is a system under which people are treated as property to be bought and sold, and are forced to work. Slaves can be held against their will from the time of their capture, purchase or birth, and deprived of the right to leave, to refuse to work, or to demand compensation...

, but was also lured by the prospect of land and fortune. A true abolitionist and successful politician, Wood won election to the Kansas senate in 1867. Though he genuinely cared about women's suffrage, Wood also hoped to make his campaign in Kansas a success so that he could get enough recognition to run for national office. He directed a strong rights campaign, forcing the Republican Kansas legislature to submit two separate bills for black and women's suffrage. The Equal Rights Association tried to sway the abolitionists to campaign alongside them, but received no response. Wood, though he claimed to support both women's and black suffrage, was only interested in women's suffrage. Many abolitionists, however, began to question Wood's motives when he openly opposed black suffrage as a member of the house in 1864. They began to heavily criticize his campaign, accusing him of promoting women's suffrage only to defeat black suffrage. Nonetheless, the equal rights campaign managed to stay afloat through the spring of 1867, due to a large female populace in Kansas that produced "the largest and most enthusiastic meetings and any one of our audiences would give a majority for women."

The 1867 defeat of women's suffrage in New York strengthened the Republicans' position against women's suffrage, and on August 31, they opened their anti-female suffrage campaign in Kansas. By the time Stanton and Anthony arrived in September, Anthony wrote that "the mischief done was irreparable," and the universal equal rights campaign, faced with a fierce Republican anti-feminist campaign and the refusal of support from ambivalent abolitionists, had fallen apart. Stanton and Anthony, desperate for support, looked towards the Democrats, who made up one-fourth of the Kansas legislature. They, however, expressed opposition to both women's and black suffrage and refused to lend aid. One wealthy Democrat, George Francis Train

George Francis Train

George Francis Train was an entrepreneurial businessman who organized the clipper ship line that sailed around Cape Horn to San Francisco; he organized the Union Pacific Railroad and the Credit Mobilier in the United States, and a horse tramway company in England while there during the American...

, a former Copperhead

Copperheads (politics)

The Copperheads were a vocal group of Democrats in the Northern United States who opposed the American Civil War, wanting an immediate peace settlement with the Confederates. Republicans started calling anti-war Democrats "Copperheads," likening them to the venomous snake...

, was willing to help Anthony and Stanton. Train was blatantly racist, and he campaigned by attacking black suffrage. Though his racist standpoint conflicted with the policy set forth by the Equal Rights Association, Stanton and Anthony, with no other political allies to turn to, chose to work with Train to keep women's suffrage alive in Kansas, although they had long been abolitionists.

The results of the Kansas election saw both women's and black suffrage defeated, with black suffrage receiving 10,483 votes and women's receiving 9,070. With the defeat, equal rights activists were forced to realize that their campaign had failed.

The failure of the campaign stemmed from the tensions within the Equal Rights Association. The major problem arose from the fact that many members were feminists and abolitionists torn between supporting suffrage, or fighting for freedmen and women at the same time.

Wyoming, Colorado, and Idaho

The first territorial legislature of the Wyoming TerritoryWyoming Territory

The Territory of Wyoming was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from July 25, 1868, until July 10, 1890, when it was admitted to the Union as the State of Wyoming. Cheyenne was the territorial capital...

granted women suffrage in 1869. In 1890, Wyoming was admitted to the Union as the first state that allowed women to vote, and in fact insisted it would not accept statehood without keeping suffrage. In 1893, voters of Colorado

Colorado

Colorado is a U.S. state that encompasses much of the Rocky Mountains as well as the northeastern portion of the Colorado Plateau and the western edge of the Great Plains...

made that state the second of the woman suffrage states and the first state where the men voted to give women the right to vote. In 1896 Idaho approved a constitutional amendment in statewide vote giving women the right to vote.

Utah

The Mormon issue made the Utah situation unique. In 1870 the Utah TerritoryUtah Territory

The Territory of Utah was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from September 9, 1850, until January 4, 1896, when the final extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Utah....

, controlled by Mormons, gave women the right to vote. However, in 1887, Congress disenfranchised Utah women with the Edmunds–Tucker Act, which was designed to weaken the Mormons politically and punish them for polygamy. In 1867-96, eastern activists promoted woman suffrage in Utah as an experiment, and as a way to eliminate polygamy. They were Presbyterians and other Protestants convinced that Mormonism was a non-Christian cult that grossly mistreated women. The Mormons promoted woman suffrage to counter the negative image of downtrodden Mormon women. The Mormons dropped the polygamy requirement in 1890 and in 1895 Utah adopted a constitution restoring the right of woman suffrage. Congress admitted Utah as a state with that constitution in 1896.

Washington

In 1854, Washington became one of the first territories to attempt granting voting rights to women; the legislative measure was defeated by only one vote. In 1871, the Washington Women's Suffrage Association was formed, largely attributable to a crusade through Washington and Oregon led by Susan B. Anthony and Abigail Scott Duniway. The late nineteenth century saw a seesaw of bills passed by the Territorial Legislature and subsequently overturned by the Territorial Supreme Court, as the competing interests of the suffrage movement and the liquor industry (which was being damaged by the women's vote) battled over the issue. The first successful bill passed in 1883 (overturned in 1887), the next in 1888 (overturned the same year). The women's suffrage movement next hoped to secure the right to vote via voter referendum, first in 1889 (the same year Washington achieved statehood), and again in 1898, but both referendum bids were unsuccessful. A constitutional amendment finally granted women the right to vote in 1910.California

California's voters granted women's suffrage in 1911, when they adopted Proposition 4California Proposition 4 (1911)

Proposition 4 of 1911 was an amendment of the Constitution of California that granted women the right to vote in the state for the first time. It was proposed by the California State Legislature and approved by voters in a referendum held as part of a special election on 10 October 1911...

. Clara Elizabeth Chan Lee

Clara Elizabeth Chan Lee

Clara Elizabeth Chan Lee was the first Chinese American woman to register to vote in the United States. She registered to vote on November 8, 1911 in California.-Biography:...

(October 21, 1886 – October 5, 1993) was the first Chinese American woman voter in the United States. She registered to vote on November 8, 1911 in California.

Oregon, Montana, Arizona

One after another, western statesWestern United States

.The Western United States, commonly referred to as the American West or simply "the West," traditionally refers to the region comprising the westernmost states of the United States. Because the U.S. expanded westward after its founding, the meaning of the West has evolved over time...

granted the right of voting to their women citizens, the only opposition being presented by the liquor interests and the machine politicians. In Oregon, Abigail Scott Duniway

Abigail Scott Duniway

Abigail Scott Duniway was an American women's rights advocate, newspaper editor and writer, whose efforts were instrumental in gaining voting rights for women.-Biography:...

(1834 – 1915) was the long-time leader, supporting the cause through speeches and her weekly newspaper The New Northwest, (1871-1887). Suffrage was won in 1912 by activists who used the new initiative processes. Montana's men gave women the vote in 1914, and together they proceeded to elect the first woman to the United States Congress in 1916, Jeannette Rankin

Jeannette Rankin

Jeannette Pickering Rankin was the first woman in the US Congress. A Republican, she was elected statewide in Montana in 1916 and again in 1940. A lifelong pacifist, she voted against the entry of the United States into both World War I in 1917 and World War II in 1941, the only member of Congress...

.

Arizona became a state in 1912, but it had many conservative Southerners and its new constitution did not include women's suffrage. Activists formed the Arizona Equal Suffrage Association (AESA) and launched a campaign to win the vote. Their tactics were to reach out to progressive organizations for endorsements, winning the support of influential political and civic leaders, and getting help from NAWSA for speakers and funds. AESA sent delegations to the Republican and Democratic state conventions to argue for their support. The tactics worked and the men voted for woman suffrage in the general election held on 5 November 1912.

New York

Feminists, knowing that women's suffrage could not succeed without support, put their hope in the Equal Rights Association and pushed for a campaign for universal suffrageUniversal suffrage

Universal suffrage consists of the extension of the right to vote to adult citizens as a whole, though it may also mean extending said right to minors and non-citizens...

. From April until November 1867, women furiously campaigned, distributing thousands of pamphlets and speaking in numerous locations for the cause. Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Elizabeth Cady Stanton was an American social activist, abolitionist, and leading figure of the early woman's movement...

focused their attentions on New York

New York

New York is a state in the Northeastern region of the United States. It is the nation's third most populous state. New York is bordered by New Jersey and Pennsylvania to the south, and by Connecticut, Massachusetts and Vermont to the east...

, while Stone and Blackwell headed to Kansas, where the November election would be taking place.

During the New York Constitutional Convention, held on June 4, 1867, Horace Greeley

Horace Greeley

Horace Greeley was an American newspaper editor, a founder of the Liberal Republican Party, a reformer, a politician, and an outspoken opponent of slavery...

, the chairman of the committee on Suffrage and an ardent supporter of women's suffrage over the previous 20 years, betrayed the women's movement and submitted a report in favor of removal of property qualification for free black men, but against women's suffrage. New York legislators supported the report by a vote of 125 to 19.

Harriot Stanton Blatch, the daughter of Elizabeth Cady Stanton, focused on New York where she succeeded in mobilizing many working-class women, even as she continued to collaborate with prominent society women. She could organize militant street protests while still working expertly in backroom politics to neutralize the opposition of Tammany Hall politicians who feared the women would vote for prohobition. New York finally joined the procession in 1917 after Tammany Hall

Tammany Hall

Tammany Hall, also known as the Society of St. Tammany, the Sons of St. Tammany, or the Columbian Order, was a New York political organization founded in 1786 and incorporated on May 12, 1789 as the Tammany Society...

ended its opposition.

New Jersey

New JerseyNew Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Northeastern and Middle Atlantic regions of the United States. , its population was 8,791,894. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York, on the southeast and south by the Atlantic Ocean, on the west by Pennsylvania and on the southwest by Delaware...

, on confederation of the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

following the Revolutionary War

American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War , the American War of Independence, or simply the Revolutionary War, began as a war between the Kingdom of Great Britain and thirteen British colonies in North America, and ended in a global war between several European great powers.The war was the result of the...

, placed only one restriction on the general suffrage—the possession of at least £50 (about $ adjusted for inflation) in cash or property. In 1790, the law was revised to include women specifically, and in 1797 the election laws referred to a voter as "he or she". Female voters became so objectionable to professional politicians, that in 1807 the law was revised to exclude them. Later, the 1844 constitution

History of the New Jersey State Constitution

Originally, the state of New Jersey was a single British colony, the Province of New Jersey. After the English Civil War, Charles II assigned New Jersey as a proprietary colony to be held jointly by Sir George Carteret and John Berkeley, 1st Baron Berkeley of Stratton. Eventually, the collection of...

banned women voting, the 1947 one then allowed it—but, by 1947, all state constitutional provisions that barred women from voting had been rendered ineffective by the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution prohibits any United States citizen to be denied the right to vote based on sex. It was ratified on August 18, 1920....

in 1920.

Maryland

Etta Maddox graduated from Baltimore Law School in 1901 but was not allowed to take the bar examination in the state of Maryland. She and her attorney, Howard Bryant, filed a brief with the Court of Appeals of Maryland to determine if she has a right to take the bar examination. The Court of Appeals of Maryland said no, since they did not have the power to change a law as legislature intended it; only legislature has that power. Therefore, Maddox, along with other women attorneys from other states, went to Maryland's General Assembly. In 1902 Senator Jacob M. Moses introduced a bill intending to change the law to including women to be permitted to practice law in Maryland; which was passed. Maddox took the bar examination and was sworn in as a member of the bar in September 1902.Illinois

In 1891, Ellen MartinEllen A. Martin

Ellen Annette Martin was an early and little-known American attorney who achieved an early victory in securing women's suffrage in Illinois...

became the first Illinois woman to vote in Lombard

Lombard, Illinois

Lombard, "The Lilac Village", is a suburb of Chicago in DuPage County, Illinois. The population was 42,322 at the 2000 census. The United States Census Bureau estimated the population in 2004 to be 42,975.-History:...

, after noting that Lombard's charter preempted Illinois law and did not mention gender. The charter was quickly amended after Martin and 14 other women voted in the 1891 elections.

In 1912, Grace Wilbur Trout, then head of the Chicago Political Equality League, was elected president of the state organization. Changing her tactics from a confrontational style of lobbying the state legislature, she turned to building the organization internally. She made sure that a local organization was started in every Senate district. One of her assistants, Elizabeth Booth

Elizabeth Booth

Elizabeth Booth was a resident of Salem, Massachusetts who in 1692 during the Salem Witch Trials accused John Proctor of serial murder, leading to his execution for witchcraft.-References:...

, cut up a Blue Book

Blue book

Blue book or Bluebook is a term often referring to an almanac or other compilation of statistics and information. The term dates back to the 15th century, when large blue velvet-covered books were used for record-keeping by the Parliament of the United Kingdom.- Government :* At the European...

government directory and made file cards for each of the members of the General Assembly

Illinois General Assembly

The Illinois General Assembly is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Illinois and comprises the Illinois House of Representatives and the Illinois Senate. The General Assembly was created by the first state constitution adopted in 1818. Illinois has 59 legislative districts, with two...

. Armed with the names, four lobbyists went to Springfield

Springfield, Illinois

Springfield is the third and current capital of the US state of Illinois and the county seat of Sangamon County with a population of 117,400 , making it the sixth most populated city in the state and the second most populated Illinois city outside of the Chicago Metropolitan Area...

to persuade one legislator at a time to support suffrage for women. In 1913, first-term Speaker of the House, Democrat Champ Clark, told Trout that he would submit the bill for a final vote, if there was support for the bill in Illinois. Trout enlisted her network, and while in Chicago

Chicago

Chicago is the largest city in the US state of Illinois. With nearly 2.7 million residents, it is the most populous city in the Midwestern United States and the third most populous in the US, after New York City and Los Angeles...

over the weekend, Clark received a phone call every 15 minutes, day and night. On returning to Springfield he found a deluge of telegrams and letters from around the state all in favor of suffrage. By acting quietly and quickly, Trout had caught the opposition off guard.

Edward Fitzsimmons Dunne

Edward Fitzsimmons Dunne was an American politician who was the 24th Governor of Illinois from 1913 to 1917 and previously served as the 38th mayor of Chicago from April 5, 1905 to 1907.-Early years:...

signed the bill in the presence of Trout, Booth and union labor leader Margaret Healy.

Women in Illinois could now vote for presidential electors and for all local offices not specifically named in the Illinois Constitution

Illinois Constitution

The Constitution of the State of Illinois is the governing document of the state of Illinois. There have been four Illinois Constitutions; the fourth and current version was adopted in 1970.-History:...

. However, they still could not vote for state representative, congressman or governor; and they still had to use separate ballots and ballot boxes. But by virtue of this law, Illinois had become the first state east of the Mississippi River

Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the largest river system in North America. Flowing entirely in the United States, this river rises in western Minnesota and meanders slowly southwards for to the Mississippi River Delta at the Gulf of Mexico. With its many tributaries, the Mississippi's watershed drains...

to grant women the right to vote for President of the United States

President of the United States

The President of the United States of America is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president leads the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces....

. Carrie Chapman Catt

Carrie Chapman Catt

Carrie Chapman Catt was a women's suffrage leader who campaigned for the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution which gave U.S. women the right to vote in 1920...

wrote,

"The effect of this victory upon the nation was astounding. When the first Illinois election took place in April, (1914) the press carried the headlines that 250,000 women had voted in Chicago. Illinois, with its large electoral vote of 29, proved the turning point beyond which politicians at last got a clear view of the fact that women were gaining genuine political power."

Besides the passage of the Illinois Municipal Voting Act, 1913 was also a significant year in other facets of the women's suffrage movement. In Chicago, African American

African American

African Americans are citizens or residents of the United States who have at least partial ancestry from any of the native populations of Sub-Saharan Africa and are the direct descendants of enslaved Africans within the boundaries of the present United States...

anti-lynching

Lynching in the United States

Lynching, the practice of killing people by extrajudicial mob action, occurred in the United States chiefly from the late 18th century through the 1960s. Lynchings took place most frequently in the South from 1890 to the 1920s, with a peak in the annual toll in 1892.It is associated with...

crusader Ida B. Wells

Ida B. Wells

Ida Bell Wells-Barnett was an African American journalist, newspaper editor and, with her husband, newspaper owner Ferdinand L. Barnett, an early leader in the civil rights movement. She documented lynching in the United States, showing how it was often a way to control or punish blacks who...

-Barnett founded the Alpha Suffrage Club

Alpha Suffrage Club

The Alpha Suffrage Club is believed to be the first black women's suffrage association in the United States. It began in Chicago, Illinois in 1913 under the initiative of Ida B. Wells-Barnett and her white colleague, Belle Squire. The club had many achievements, and gained popularity within the...

, the first such organization for Negro women in Illinois. Although white women as a group were sometimes ambivalent about obtaining the franchise, African American women were almost universally in favor of gaining the vote to help end their sexual exploitation, promote their educational opportunities and protect those who were wage earners. African-American women often found themselves fighting both sexism and racism. As a result there was an African-American Woman Suffrage Movement

African-American Woman Suffrage Movement

As the women's suffrage movement gained popularity, African-American women were increasinglymarginalized. African-American women dealt not only with the sexism of being withheld the vote, but also the racism of white suffragists. The struggle for the vote did not end with the ratification of the...

.

National efforts

Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly referred to as Washington, "the District", or simply D.C., is the capital of the United States. On July 16, 1790, the United States Congress approved the creation of a permanent national capital as permitted by the U.S. Constitution....

When Wells tried to line up with her Illinois sisters, she was asked to go to the end of the line so as not to offend and alienate the southern women marchers. Wells feigned agreement, but much to the shock of Trout, she joined the Illinois delegation once the parade started.

As the suffragists started down Pennsylvania Avenue

Pennsylvania Avenue

Pennsylvania Avenue is a street in Washington, D.C. that joins the White House and the United States Capitol. Called "America's Main Street", it is the location of official parades and processions, as well as protest marches...

, the crowd became abusive and started to close in, knocking the marchers around with hostility. With local police doing little to keep control, the cavalry was called in as 100 women were hospitalized. Many suffragists concluded that public protests might be the quickest route to universal franchise.

Nineteenth Amendment

United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives is one of the two Houses of the United States Congress, the bicameral legislature which also includes the Senate.The composition and powers of the House are established in Article One of the Constitution...

but was defeated by a vote of 204 to 174. Another bill was brought before the House on January 10, 1918. On the evening before, President Wilson

Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson was the 28th President of the United States, from 1913 to 1921. A leader of the Progressive Movement, he served as President of Princeton University from 1902 to 1910, and then as the Governor of New Jersey from 1911 to 1913...

made a strong and widely published appeal to the House to pass the bill. It was passed by two-thirds of the House, with only one vote to spare. The vote was then carried into the Senate

United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper house of the bicameral legislature of the United States, and together with the United States House of Representatives comprises the United States Congress. The composition and powers of the Senate are established in Article One of the U.S. Constitution. Each...

. Again President Wilson made an appeal, but on September 30, 1918, the amendment fell two votes short of passage. On February 10, 1919, it was again voted upon, and then it was lost by only one vote.

There was considerable anxiety among politicians of both parties to have the amendment passed and made effective before the general elections of 1920, so the President called a special session of Congress, and a bill, introducing the amendment, was brought before the House again. On May 21, 1919, it was passed, 42 votes more than necessary being obtained. On June 4, 1919, it was brought before the Senate, and after a long discussion it was passed, with 56 ayes and 25 nays. Within a few days, Illinois

Illinois

Illinois is the fifth-most populous state of the United States of America, and is often noted for being a microcosm of the entire country. With Chicago in the northeast, small industrial cities and great agricultural productivity in central and northern Illinois, and natural resources like coal,...

, Wisconsin

Wisconsin

Wisconsin is a U.S. state located in the north-central United States and is part of the Midwest. It is bordered by Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake Michigan to the east, Michigan to the northeast, and Lake Superior to the north. Wisconsin's capital is...

, and Michigan

Michigan

Michigan is a U.S. state located in the Great Lakes Region of the United States of America. The name Michigan is the French form of the Ojibwa word mishigamaa, meaning "large water" or "large lake"....

ratified the amendment, their legislatures being then in session. Other states followed suit at a regular pace, until the amendment had been ratified by 35 of the necessary 36 state legislatures. After Washington on March 22, 1920, ratification languished for months. Finally, on August 18, 1920, Tennessee

Tennessee

Tennessee is a U.S. state located in the Southeastern United States. It has a population of 6,346,105, making it the nation's 17th-largest state by population, and covers , making it the 36th-largest by total land area...

narrowly ratified the Nineteenth Amendment

Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution prohibits any United States citizen to be denied the right to vote based on sex. It was ratified on August 18, 1920....

, making it the law throughout the United States.

The final states to ratify the 19th Amendment were Georgia, North Carolina, and Louisiana, in 1970 and 1971. South Carolina finally ratified it in 1973, but Mississippi not until 1984.

Results

Politicians responded to the newly enlarged electorate by emphasizing issues of special interest to women, especially prohibition, child health, public schools, and world peace. Women did respond to these issues, but in terms of general voting they shared the same outlook and the same voting behavior as men.The suffrage organization NAWSA became the League of Women Voters

League of Women Voters

The League of Women Voters is an American political organization founded in 1920 by Carrie Chapman Catt during the last meeting of the National American Woman Suffrage Association approximately six months before the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution gave women the right to vote...

and Alice Paul's National Woman's Party

National Woman's Party

The National Woman's Party , was a women's organization founded by Alice Paul in 1915 that fought for women's rights during the early 20th century in the United States, particularly for the right to vote on the same terms as men...

began lobbying for full equality and the Equal Rights Amendment

Equal Rights Amendment

The Equal Rights Amendment was a proposed amendment to the United States Constitution. The ERA was originally written by Alice Paul and, in 1923, it was introduced in the Congress for the first time...

which would pass Congress during the second wave of the women's movement in 1972 (but it was not ratified and never took effect). The main surge of women voting came in 1928, when the big-city machines realized they needed the support of women to elect Al Smith

Al Smith

Alfred Emanuel Smith. , known in private and public life as Al Smith, was an American statesman who was elected the 42nd Governor of New York three times, and was the Democratic U.S. presidential candidate in 1928...

, while rural dries mobilized women to support Prohibition and vote for Republican Herbert Hoover

Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover was the 31st President of the United States . Hoover was originally a professional mining engineer and author. As the United States Secretary of Commerce in the 1920s under Presidents Warren Harding and Calvin Coolidge, he promoted partnerships between government and business...

. Catholic women were reluctant to vote in the early 1920s, but they registered in very large numbers for the 1928 election--the first in which Catholicism was a major issue. A few women were elected to office, but none became especially prominent during this time period. Overall, the women's rights movement was dormant in the 1920s as Susan B. Anthony and the other prominent activists were dead and apart from Alice Paul

Alice Paul

Alice Stokes Paul was an American suffragist and activist. Along with Lucy Burns and others, she led a successful campaign for women's suffrage that resulted in the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1920.-Activism: Alice Paul received her undergraduate education from...

few younger women came along to replace them.

In states where women were allowed to vote, the passage of Prohibition laws has been determined to have been more likely. In United States presidential elections, women's suffrage has been charged with changing the outcome of presidential elections. Barack Obama won both the male and female vote in 2008.

It has been argued that without women's suffrage, the Republicans would have swept every election but one between 1968 and 1974. Another result of Women's suffrage is the steady rise of government spending between the 1920's and the present, as women are more risk averse than men and support "safety net" type income distribution and social welfare programs such as Medicare, Social Security, and public education.

This came about in direct contradiction to what was expected by some writers prior to the passage of women's suffrage. In fact, it was stated by one opponent to suffrage that women voters would be "thriftier and less wasteful than men."

Biographical

- Cynthia LeonardCynthia LeonardCynthia Leonard was a suffragist, aid worker and writer, notable for her pioneering efforts toward social reform in the 19th Century. Born Cynthia Hicks Van Name, in Buffalo, New York, she married Charles E. Leonard in 1852...

- Frances WillardFrances Willard (suffragist)Frances Elizabeth Caroline Willard was an American educator, temperance reformer, and women's suffragist. Her influence was instrumental in the passage of the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution...

- Ida B. WellsIda B. WellsIda Bell Wells-Barnett was an African American journalist, newspaper editor and, with her husband, newspaper owner Ferdinand L. Barnett, an early leader in the civil rights movement. She documented lynching in the United States, showing how it was often a way to control or punish blacks who...

- Ida Husted HarperIda Husted HarperIda Husted Harper was a prominent figure in the United States women's suffrage movement. She was an American author and journalist who wrote primarily to document the movement and show support of its ideals....

- Mary Church TerrellMary Church TerrellMary Church Terrell , daughter of former slaves, was one of the first African-American women to earn a college degree. She became an activist who led several important associations and worked for civil rights and suffrage....

- Mary LivermoreMary LivermoreMary Livermore, born Mary Ashton Rice, was an American journalist and advocate of women's rights.-Biography:...

- Sojourner TruthSojourner TruthSojourner Truth was the self-given name, from 1843 onward, of Isabella Baumfree, an African-American abolitionist and women's rights activist. Truth was born into slavery in Swartekill, New York, but escaped with her infant daughter to freedom in 1826. After going to court to recover her son, she...

- Alice PaulAlice PaulAlice Stokes Paul was an American suffragist and activist. Along with Lucy Burns and others, she led a successful campaign for women's suffrage that resulted in the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1920.-Activism: Alice Paul received her undergraduate education from...

Historical

- African-American Woman Suffrage MovementAfrican-American Woman Suffrage MovementAs the women's suffrage movement gained popularity, African-American women were increasinglymarginalized. African-American women dealt not only with the sexism of being withheld the vote, but also the racism of white suffragists. The struggle for the vote did not end with the ratification of the...

- Anti-suffragismAnti-suffragismAnti-suffragism was a political movement composed mainly of women, begun in the late 19th century in order to campaign against women's suffrage in the United States and United Kingdom...

- Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against WomenConvention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against WomenThe Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination against Women is an international convention adopted in 1979 by the United Nations General Assembly....

- League of Women VotersLeague of Women VotersThe League of Women Voters is an American political organization founded in 1920 by Carrie Chapman Catt during the last meeting of the National American Woman Suffrage Association approximately six months before the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution gave women the right to vote...

- List of the first female holders of political offices in Europe

- National American Woman Suffrage AssociationNational American Woman Suffrage AssociationThe National American Woman Suffrage Association was an American women's rights organization formed in May 1890 as a unification of the National Woman Suffrage Association and the American Woman Suffrage Association...

- Nineteenth Amendment to the United States ConstitutionNineteenth Amendment to the United States ConstitutionThe Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution prohibits any United States citizen to be denied the right to vote based on sex. It was ratified on August 18, 1920....