György Dózsa

Encyclopedia

György Dózsa was a Székely

Hungarian man-at-arms

(and by some accounts, a nobleman

) from Transylvania

, Kingdom of Hungary

who led a peasants' revolt

against the kingdom's landed nobility

. He was eventually caught, tortured, and executed along with his followers, and remembered as both a Christian

martyr

and a dangerous criminal. During the reign of king Vladislas II of Hungary (1490–1516), royal power declined in favour of the magnates, who used their power to curtail the peasants’ freedom.

), Dózsa was a soldier of fortune

who won a reputation for valour in the wars against the Ottoman Empire

. The Hungarian chancellor

, Tamás Bakócz

, on his return from the Holy See

in 1514 (with a papal bull

issued by Leo X

authorising a crusade against the Ottomans), appointed Dózsa to organize and direct the movement. Within a few weeks he had gathered an army of some 100,000 so-called kuruc

, consisting for the most part of peasants, wandering students

, friar

s, and parish

priests - some of the lowest-ranking groups of medieval society. They assembled in their counties

, and by the time Dózsa had provided them with some military training, they began to air the grievances of their status.

No measures had been taken to supply these voluntary crusaders with food or clothing; as harvest-time approached, the landlord

s commanded them to return to reap the fields, and, on their refusing to do so, proceeded to maltreat their wives and families and set their armed retainers

upon the local peasantry. The rebellious, antilandlord sentiment of these “Crusaders” became apparent during their march across the Great Alföld, and Bakócz canceled the campaign. Instantly, the movement was diverted from its original object, and the peasants and their leaders began a war of vengeance against the landlords.

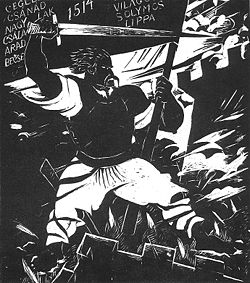

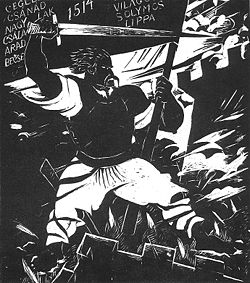

, Lőrinc Mészáros. The rebellion became more dangerous when the towns joined on the side of the peasants, and in Buda

and other places the cavalry

sent against the Kuruc were unhorsed as they passed through the gates. The rebellion spread quickly, principally in the central or purely Magyar provinces, where hundreds of manor house

s and castle

s were burnt and thousands of the gentry

killed by impalement, crucifixion, and other methods. Dózsa's camp at Cegléd was the centre of the jacquerie

, as all raids in the surrounding area had it as their starting point.

In reaction, the papal bull was revoked, and King Vladislaus II

issued a proclamation commanding the peasantry to return to their homes under pain of death. By this time the rising had attained the dimensions of a revolution

; all the vassal

s of the kingdom were called out against it, and soldiers of fortune were hired in haste from the Republic of Venice

, Bohemia

and the Holy Roman Empire

. Meanwhile, Dózsa had captured the city and fortress of Csanád

(today's Cenad), and signaled his victory by impaling

the bishop

and the castellan

.

Subsequently, at Arad

, Lord Treasurer István Telegdy was seized and tortured to death. In general, however, the rebels only executed particularly vicious or greedy noblemen; those who freely submitted were released on parole

. Dózsa not only never broke his given word, but frequently assisted the escape of fugitives. He was unable to consistently control his followers, however, and many of them hunted down rivals. At first, it also seemed as if the powers in the Kingdom were incapable of coping with him.

In the course of the summer he took the fortresses of Arad, Lippa

In the course of the summer he took the fortresses of Arad, Lippa

(today also called Lipova) and Világos (today also called Şiria), and provided himself with cannon

s and trained gunners; and one of his bands advanced to within 25 kilometers of the capital. But his ill-armed ploughmen were overmatched by the heavy cavalry

of the nobles. Dózsa himself had apparently become demoralized by success: after Csanád

, he issued proclamations which can be described as millenarian

.

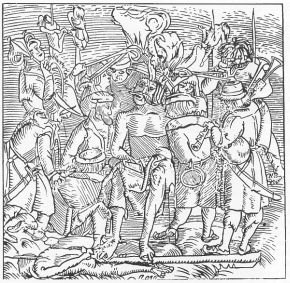

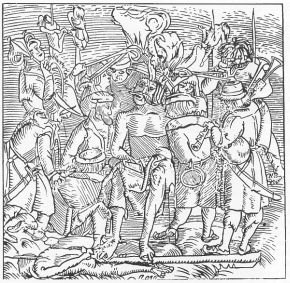

As his suppression had become a political necessity, he was routed at Temesvár (today Timişoara

) by an army of 20,000 led by John Zápolya

and István Báthory

. He was captured after the battle, and condemned to sit on a heated smoldering iron throne with a heated iron crown on his head and a heated sceptre in his hand (mocking at his ambition to be king). While Dózsa was suffering, a procession of 9 fellow rebels, who had been starved beforehand, were led to such throne. In the lead was Dózsa's younger brother, Gergely, who was cut in three before Dózsa despite Dózsa asking for Gergely to be spared. Next, executioners removed hot pliers from fire and forced them into Dózsa's skin. After pulling flesh from him, the remaining rebels were ordered to bite where the hot iron had been inserted and to swallow the flesh. Those who refused, about 3 or 4, were simply cut up which prompted the remaining rebels to do as commanded. In the end, Dózsa died on the throne of iron from the damage that was inflicted while the rebels who obeyed were let go without further harm.

The revolt was repressed but some 70,000 peasants were tortured. György's execution, and the brutal suppression of the peasants, greatly aided the 1526 Turkish invasion as the Hungarians were no longer a politically united people. The Ottoman Turks were thus able to enter the country. Another consequence was the creation of new laws, an effort in the Hungarian Diet led by István Werbőczy

. The resulting Tripartitum elaborated the Doctrine of the Holy Crown but also greatly enhanced the status of nobility, erecting an iron curtain between Hungarians until 1848 with the abolishment of serfdom

.

Today, on the site of the martyrdom of the hot throne, there is the statue of The Virgin Mary, built by architect László Székely and sculptor György Kiss

Today, on the site of the martyrdom of the hot throne, there is the statue of The Virgin Mary, built by architect László Székely and sculptor György Kiss

. According to the legend, during György Dózsa's torture, some monks saw in his ear the image of Mary. The first statue was raised in 1865, with the actual monument raised in 1906. A square, a busy six-lane avenue next to Hősök tere and a metro station in Budapest

(Dózsa György út

) bear his name, and it is one of the most popular street name

s in Hungarian villages (alongside Sándor Petőfi

's and Lajos Kossuth

's). Hungarian opera composer Ferenc Erkel wrote an opera about him (see Dózsa György

).

A number of streets in several cities of Romania

were named Gheorghe Doja, and his revolutionary image and Transylvanian background were drawn upon during the Communist

regime of Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej

. Also, a number of streets in serval cities of Serbia

were named "Ulica Doža Đerđa". "The Hungarian national component of the movement led by him was de-emphasized, while its strong antifeudal character was highlighted.

Székely

The Székelys or Székely , sometimes also referred to as Szeklers , are a subgroup of the Hungarian people living mostly in the Székely Land, an ethno-cultural region in eastern Transylvania, Romania...

Hungarian man-at-arms

Man-at-arms

Man-at-arms was a term used from the High Medieval to Renaissance periods to describe a soldier, almost always a professional warrior in the sense of being well-trained in the use of arms, who served as a fully armoured heavy cavalryman...

(and by some accounts, a nobleman

Nobility and royalty of the Kingdom of Hungary

This article deals with titles of the nobility and royalty of the Kingdom of Hungary.-Earlier usage :Before the accession of the Habsburgs, the nobility was structured according to the offices held in the administration of the Kingdom...

) from Transylvania

Transylvania

Transylvania is a historical region in the central part of Romania. Bounded on the east and south by the Carpathian mountain range, historical Transylvania extended in the west to the Apuseni Mountains; however, the term sometimes encompasses not only Transylvania proper, but also the historical...

, Kingdom of Hungary

Kingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary comprised present-day Hungary, Slovakia and Croatia , Transylvania , Carpatho Ruthenia , Vojvodina , Burgenland , and other smaller territories surrounding present-day Hungary's borders...

who led a peasants' revolt

Popular revolt in late medieval Europe

Popular revolts in late medieval Europe were uprisings and rebellions by peasants in the countryside, or the bourgeois in towns, against nobles, abbots and kings during the upheavals of the 14th through early 16th centuries, part of a larger "Crisis of the Late Middle Ages"...

against the kingdom's landed nobility

Landed nobility

Landed nobility is a category of nobility in various countries over the history, for which landownership was part of their noble privileges. Their character depends on the country.*Landed gentry is the landed nobility in the United Kingdom and Ireland....

. He was eventually caught, tortured, and executed along with his followers, and remembered as both a Christian

Christianity

Christianity is a monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus as presented in canonical gospels and other New Testament writings...

martyr

Martyr

A martyr is somebody who suffers persecution and death for refusing to renounce, or accept, a belief or cause, usually religious.-Meaning:...

and a dangerous criminal. During the reign of king Vladislas II of Hungary (1490–1516), royal power declined in favour of the magnates, who used their power to curtail the peasants’ freedom.

Outbreak of the rebellion

Born in Dálnok (today DalnicDalnic

Dalnic is a commune in Covasna County, Romania. Composed of a single village, Dalnic, it became an independent commune when it split from Moacşa in 2004. The commune has an absolute Székely Hungarian majority. For demographics see Moacşa....

), Dózsa was a soldier of fortune

Mercenary

A mercenary, is a person who takes part in an armed conflict based on the promise of material compensation rather than having a direct interest in, or a legal obligation to, the conflict itself. A non-conscript professional member of a regular army is not considered to be a mercenary although he...

who won a reputation for valour in the wars against the Ottoman Empire

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman EmpireIt was usually referred to as the "Ottoman Empire", the "Turkish Empire", the "Ottoman Caliphate" or more commonly "Turkey" by its contemporaries...

. The Hungarian chancellor

Chancellor

Chancellor is the title of various official positions in the governments of many nations. The original chancellors were the Cancellarii of Roman courts of justice—ushers who sat at the cancelli or lattice work screens of a basilica or law court, which separated the judge and counsel from the...

, Tamás Bakócz

Tamás Bakócz

Tamás Bakócz was a Hungarian archbishop, cardinal and statesman.In sources in Croatian, Tamás Bakócz is also referred under the name Toma Bakač....

, on his return from the Holy See

Holy See

The Holy See is the episcopal jurisdiction of the Catholic Church in Rome, in which its Bishop is commonly known as the Pope. It is the preeminent episcopal see of the Catholic Church, forming the central government of the Church. As such, diplomatically, and in other spheres the Holy See acts and...

in 1514 (with a papal bull

Papal bull

A Papal bull is a particular type of letters patent or charter issued by a Pope of the Catholic Church. It is named after the bulla that was appended to the end in order to authenticate it....

issued by Leo X

Pope Leo X

Pope Leo X , born Giovanni di Lorenzo de' Medici, was the Pope from 1513 to his death in 1521. He was the last non-priest to be elected Pope. He is known for granting indulgences for those who donated to reconstruct St. Peter's Basilica and his challenging of Martin Luther's 95 Theses...

authorising a crusade against the Ottomans), appointed Dózsa to organize and direct the movement. Within a few weeks he had gathered an army of some 100,000 so-called kuruc

Kuruc

The kuruc was a term used to denote the armed anti-Habsburg rebels in Royal Hungary between 1671 and 1711....

, consisting for the most part of peasants, wandering students

Medieval university

Medieval university is an institution of higher learning which was established during High Middle Ages period and is a corporation.The first institutions generally considered to be universities were established in Italy, France, and England in the late 11th and the 12th centuries for the study of...

, friar

Friar

A friar is a member of one of the mendicant orders.-Friars and monks:...

s, and parish

Parish

A parish is a territorial unit historically under the pastoral care and clerical jurisdiction of one parish priest, who might be assisted in his pastoral duties by a curate or curates - also priests but not the parish priest - from a more or less central parish church with its associated organization...

priests - some of the lowest-ranking groups of medieval society. They assembled in their counties

Administrative divisions of the Kingdom of Hungary

The following lists show the administrative divisions of the lands belonging to the Hungarian crown at selected points of time. The names are given in the main official language used in the Kingdom at the times in question....

, and by the time Dózsa had provided them with some military training, they began to air the grievances of their status.

No measures had been taken to supply these voluntary crusaders with food or clothing; as harvest-time approached, the landlord

Landlord

A landlord is the owner of a house, apartment, condominium, or real estate which is rented or leased to an individual or business, who is called a tenant . When a juristic person is in this position, the term landlord is used. Other terms include lessor and owner...

s commanded them to return to reap the fields, and, on their refusing to do so, proceeded to maltreat their wives and families and set their armed retainers

Retinue

A retinue is a body of persons "retained" in the service of a noble or royal personage, a suite of "retainers".-Etymology:...

upon the local peasantry. The rebellious, antilandlord sentiment of these “Crusaders” became apparent during their march across the Great Alföld, and Bakócz canceled the campaign. Instantly, the movement was diverted from its original object, and the peasants and their leaders began a war of vengeance against the landlords.

Successes

By this time, Dózsa was losing control of the people under his command, who had fallen under the influence of the parson of CeglédCegléd

Cegléd is a city in Pest county, Hungary, approximately southeast of the Hungarian capital, Budapest.-Name:There are discussions going on about the origin of the name of the town...

, Lőrinc Mészáros. The rebellion became more dangerous when the towns joined on the side of the peasants, and in Buda

Buda

For detailed information see: History of Buda CastleBuda is the western part of the Hungarian capital Budapest on the west bank of the Danube. The name Buda takes its name from the name of Bleda the Hun ruler, whose name is also Buda in Hungarian.Buda comprises about one-third of Budapest's...

and other places the cavalry

Cavalry

Cavalry or horsemen were soldiers or warriors who fought mounted on horseback. Cavalry were historically the third oldest and the most mobile of the combat arms...

sent against the Kuruc were unhorsed as they passed through the gates. The rebellion spread quickly, principally in the central or purely Magyar provinces, where hundreds of manor house

Manor house

A manor house is a country house that historically formed the administrative centre of a manor, the lowest unit of territorial organisation in the feudal system in Europe. The term is applied to country houses that belonged to the gentry and other grand stately homes...

s and castle

Castle

A castle is a type of fortified structure built in Europe and the Middle East during the Middle Ages by European nobility. Scholars debate the scope of the word castle, but usually consider it to be the private fortified residence of a lord or noble...

s were burnt and thousands of the gentry

Gentry

Gentry denotes "well-born and well-bred people" of high social class, especially in the past....

killed by impalement, crucifixion, and other methods. Dózsa's camp at Cegléd was the centre of the jacquerie

Jacquerie

The Jacquerie was a popular revolt in late medieval Europe by peasants that took place in northern France in the summer of 1358, during the Hundred Years' War. The revolt, which was violently suppressed after a few weeks of violence, centered in the Oise valley north of Paris...

, as all raids in the surrounding area had it as their starting point.

In reaction, the papal bull was revoked, and King Vladislaus II

Vladislaus II of Bohemia and Hungary

Vladislaus II, also known as Ladislaus Jagiellon ; was King of Bohemia from 1471 and King of Hungary from 1490 until his death in 1516...

issued a proclamation commanding the peasantry to return to their homes under pain of death. By this time the rising had attained the dimensions of a revolution

Revolution

A revolution is a fundamental change in power or organizational structures that takes place in a relatively short period of time.Aristotle described two types of political revolution:...

; all the vassal

Vassal

A vassal or feudatory is a person who has entered into a mutual obligation to a lord or monarch in the context of the feudal system in medieval Europe. The obligations often included military support and mutual protection, in exchange for certain privileges, usually including the grant of land held...

s of the kingdom were called out against it, and soldiers of fortune were hired in haste from the Republic of Venice

Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice or Venetian Republic was a state originating from the city of Venice in Northeastern Italy. It existed for over a millennium, from the late 7th century until 1797. It was formally known as the Most Serene Republic of Venice and is often referred to as La Serenissima, in...

, Bohemia

Bohemia

Bohemia is a historical region in central Europe, occupying the western two-thirds of the traditional Czech Lands. It is located in the contemporary Czech Republic with its capital in Prague...

and the Holy Roman Empire

Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a realm that existed from 962 to 1806 in Central Europe.It was ruled by the Holy Roman Emperor. Its character changed during the Middle Ages and the Early Modern period, when the power of the emperor gradually weakened in favour of the princes...

. Meanwhile, Dózsa had captured the city and fortress of Csanád

Csanád

Csanád is the name of a historic administrative county of the Kingdom of Hungary. Its territory is presently in western Romania and southeastern Hungary. The capital of the county was Makó.-Geography:...

(today's Cenad), and signaled his victory by impaling

Impalement

Impalement is the traumatic penetration of an organism by an elongated foreign object such as a stake, pole, or spear, and this usually implies complete perforation of the central mass of the impaled body...

the bishop

Bishop

A bishop is an ordained or consecrated member of the Christian clergy who is generally entrusted with a position of authority and oversight. Within the Catholic Church, Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox Churches, in the Assyrian Church of the East, in the Independent Catholic Churches, and in the...

and the castellan

Castellan

A castellan was the governor or captain of a castle. The word stems from the Latin Castellanus, derived from castellum "castle". Also known as a constable.-Duties:...

.

Subsequently, at Arad

Arad, Romania

Arad is the capital city of Arad County, in western Romania, in the Crişana region, on the river Mureş.An important industrial center and transportation hub, Arad is also the seat of a Romanian Orthodox archbishop and features two universities, a Romanian Orthodox theological seminary, a training...

, Lord Treasurer István Telegdy was seized and tortured to death. In general, however, the rebels only executed particularly vicious or greedy noblemen; those who freely submitted were released on parole

Parole

Parole may have different meanings depending on the field and judiciary system. All of the meanings originated from the French parole . Following its use in late-resurrected Anglo-French chivalric practice, the term became associated with the release of prisoners based on prisoners giving their...

. Dózsa not only never broke his given word, but frequently assisted the escape of fugitives. He was unable to consistently control his followers, however, and many of them hunted down rivals. At first, it also seemed as if the powers in the Kingdom were incapable of coping with him.

Downfall, execution

Lipova, Arad

Lipova is a town in Romania, Arad County, located in the Banat region of western Transylvania. It is situated at a distance of 34 km from Arad, the county capital, at the contact zone of the Mureș River with the Zarand Mountains, Western Plateau and Lipovei Hills...

(today also called Lipova) and Világos (today also called Şiria), and provided himself with cannon

Cannon

A cannon is any piece of artillery that uses gunpowder or other usually explosive-based propellents to launch a projectile. Cannon vary in caliber, range, mobility, rate of fire, angle of fire, and firepower; different forms of cannon combine and balance these attributes in varying degrees,...

s and trained gunners; and one of his bands advanced to within 25 kilometers of the capital. But his ill-armed ploughmen were overmatched by the heavy cavalry

Heavy cavalry

Heavy cavalry is a class of cavalry whose primary role was to engage in direct combat with enemy forces . Although their equipment differed greatly depending on the region and historical period, they were generally mounted on large powerful horses, and were often equipped with some form of scale,...

of the nobles. Dózsa himself had apparently become demoralized by success: after Csanád

Csanád

Csanád is the name of a historic administrative county of the Kingdom of Hungary. Its territory is presently in western Romania and southeastern Hungary. The capital of the county was Makó.-Geography:...

, he issued proclamations which can be described as millenarian

Millenarianism

Millenarianism is the belief by a religious, social, or political group or movement in a coming major transformation of society, after which all things will be changed, based on a one-thousand-year cycle. The term is more generically used to refer to any belief centered around 1000 year intervals...

.

As his suppression had become a political necessity, he was routed at Temesvár (today Timişoara

Timisoara

Timișoara is the capital city of Timiș County, in western Romania. One of the largest Romanian cities, with an estimated population of 311,586 inhabitants , and considered the informal capital city of the historical region of Banat, Timișoara is the main social, economic and cultural center in the...

) by an army of 20,000 led by John Zápolya

John Zápolya

John Zápolya was King of Hungary from 1526 to 1540. His rule was disputed by Archduke Ferdinand I, who also claimed the title King of Hungary between 1526 and 1540. He was the voivode of Transylvania before his coronation.- Biography :...

and István Báthory

István Báthory

Stephen VIII Báthory was a Hungarian noble.He was a son of Nicholas Báthory of the Somlyó branch of the Báthory family.In 1521, he was appointed deputy voivode of Transylvania, serving under the Voivoid John Zápolya...

. He was captured after the battle, and condemned to sit on a heated smoldering iron throne with a heated iron crown on his head and a heated sceptre in his hand (mocking at his ambition to be king). While Dózsa was suffering, a procession of 9 fellow rebels, who had been starved beforehand, were led to such throne. In the lead was Dózsa's younger brother, Gergely, who was cut in three before Dózsa despite Dózsa asking for Gergely to be spared. Next, executioners removed hot pliers from fire and forced them into Dózsa's skin. After pulling flesh from him, the remaining rebels were ordered to bite where the hot iron had been inserted and to swallow the flesh. Those who refused, about 3 or 4, were simply cut up which prompted the remaining rebels to do as commanded. In the end, Dózsa died on the throne of iron from the damage that was inflicted while the rebels who obeyed were let go without further harm.

The revolt was repressed but some 70,000 peasants were tortured. György's execution, and the brutal suppression of the peasants, greatly aided the 1526 Turkish invasion as the Hungarians were no longer a politically united people. The Ottoman Turks were thus able to enter the country. Another consequence was the creation of new laws, an effort in the Hungarian Diet led by István Werbőczy

István Werboczy

István Werbőczy or Stephen Werbőcz was a Hungarian jurist and statesman who first became known as a scholar and theologian of such eminence that he was appointed to accompany the emperor Charles V to Worms, to take up the cudgels against Martin Luther.He began his political career as the deputy of...

. The resulting Tripartitum elaborated the Doctrine of the Holy Crown but also greatly enhanced the status of nobility, erecting an iron curtain between Hungarians until 1848 with the abolishment of serfdom

Serfdom

Serfdom is the status of peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to Manorialism. It was a condition of bondage or modified slavery which developed primarily during the High Middle Ages in Europe and lasted to the mid-19th century...

.

Legacy

Gyorgy Kiss

Gyorgy Kiss is a Hungarian football defender who is currently playing for Nantwich Town in the Northern Premier League Division One South.-Club career:...

. According to the legend, during György Dózsa's torture, some monks saw in his ear the image of Mary. The first statue was raised in 1865, with the actual monument raised in 1906. A square, a busy six-lane avenue next to Hősök tere and a metro station in Budapest

Budapest

Budapest is the capital of Hungary. As the largest city of Hungary, it is the country's principal political, cultural, commercial, industrial, and transportation centre. In 2011, Budapest had 1,733,685 inhabitants, down from its 1989 peak of 2,113,645 due to suburbanization. The Budapest Commuter...

(Dózsa György út

Dózsa György út

Dózsa György út is a station on the M3 line of the Budapest Metro. It is located in District XIII under Váci út at its intersection with Dózsa György Road.-Connections:*Bus: TESCO-bus*Trolleybus: 75, 79...

) bear his name, and it is one of the most popular street name

Street name

A street name or odonym is an identifying name given to a street. The street name usually forms part of the address...

s in Hungarian villages (alongside Sándor Petőfi

Sándor Petofi

Sándor Petőfi , was a Hungarian poet and liberal revolutionary. He is considered as Hungary's national poet and he was one of the key figures of the Hungarian Revolution of 1848...

's and Lajos Kossuth

Lajos Kossuth

Lajos Kossuth de Udvard et Kossuthfalva was a Hungarian lawyer, journalist, politician and Regent-President of Hungary in 1849. He was widely honored during his lifetime, including in the United Kingdom and the United States, as a freedom fighter and bellwether of democracy in Europe.-Family:Lajos...

's). Hungarian opera composer Ferenc Erkel wrote an opera about him (see Dózsa György

György Dózsa (opera)

Dózsa György is an 1867 Hungarian opera by Ferenc Erkel. It is based on the life of György Dózsa.-References: The following sources were given:*Till Géza: Opera, Zeneműkiadó, Budapest, 1985, ISBN 963 330 564 0...

).

A number of streets in several cities of Romania

Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central and Southeastern Europe, on the Lower Danube, within and outside the Carpathian arch, bordering on the Black Sea...

were named Gheorghe Doja, and his revolutionary image and Transylvanian background were drawn upon during the Communist

Romanian Communist Party

The Romanian Communist Party was a communist political party in Romania. Successor to the Bolshevik wing of the Socialist Party of Romania, it gave ideological endorsement to communist revolution and the disestablishment of Greater Romania. The PCR was a minor and illegal grouping for much of the...

regime of Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej

Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej

Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej was the Communist leader of Romania from 1948 until his death in 1965.-Early life:Gheorghe was the son of a poor worker, Tănase Gheorghiu, and his wife Ana. Gheorghiu-Dej joined the Communist Party of Romania in 1930...

. Also, a number of streets in serval cities of Serbia

Serbia

Serbia , officially the Republic of Serbia , is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central and Southeast Europe, covering the southern part of the Carpathian basin and the central part of the Balkans...

were named "Ulica Doža Đerđa". "The Hungarian national component of the movement led by him was de-emphasized, while its strong antifeudal character was highlighted.