Gustave Whitehead

Encyclopedia

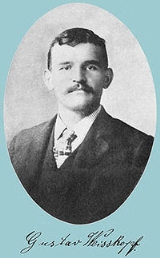

Gustave Albin Whitehead, born Gustav Albin Weisskopf (1 January 1874 – 10 October 1927) was an aviation pioneer who emigrated from Germany to the U.S., where he designed and built early flying machines and engines meant to power them.

In the decades since, several non-academic researchersThe researchers include Stella Randolph, William O'Dwyer and Andy Kosch. A German museum also makes the assertion. have promoted their belief that Whitehead made controlled, powered airplane flights more than two years before the Wright Brothers

did on 17 December 1903. These claims have repeatedly been dismissed by mainstream aviation scholars.The mainstream scholars and historians include Charles Harvard Gibbs-Smith, William F. Trimble, Tom D. Crouch, Fred Howard, and Walter J. Boyne.

Claims for Whitehead rest largely on a long local newspaper article that said he made a powered controlled flight in Connecticut in August 1901. He personally claimed credit for the feat, and he and eyewitnesses said he made several other powered flights in 1901 and 1902. Scientific American magazine published an article in September 1903 about Whitehead making motorized flights in a triplane originally designed as a glider. After 1903 publicity faded for his aeronautical efforts, which lasted from about 1897 to 1911. He lapsed into obscurity until his name was brought back to public attention by a 1935 magazine article and a 1937 book which focused attention on his life and work and led to "lively debate" among scholars, researchers, aviation enthusiasts and even Orville Wright on the question of whether Whitehead actually flew. Research in the 1960s and 70s, and pro-Whitehead books in 1966 and 1978 led to renewed examination and dismissal of the claims by aviation scholars. Since the 1980s enthusiasts in the U.S. and Germany have built working replicas of Whitehead's 1901 flying machine. Some of the replicas were built as towed gliders, while the powered ones utilized modern engines and propellers.

Whitehead was born in Leutershausen

Whitehead was born in Leutershausen

, Bavaria

, the second child of Karl Weisskopf and his wife Babetta. As a boy, he showed an interest in flight, experimenting with kite

s and earning the nickname "the flyer". He and a friend caught and tethered bird

s in an attempt to learn how they flew, an activity which police soon stopped. His parents died in 1886 and 1887, when he was a boy. He then trained as a mechanic and traveled to Hamburg

, where in 1888 he was forced to join the crew of a sailing ship. A year later, he returned to Germany, then journeyed with a family to Brazil

. He went to sea again for several years, learning more about wind, weather and bird flight.

Weisskopf arrived in the U.S. in 1893. He soon anglicized his name to Gustave Whitehead. In 1897 the Aeronautical Club of Boston hired Whitehead to build two gliders, one of which (patterned after a Lilienthal glider) was partially successful and in which Whitehead flew short distances, and toy manufacturer E. J. Horsman in New York hired Whitehead to build and operate advertising kites, and model gliders. Whitehead occupied himself with plans to provide a motor to drive one of his gliders.

's Schenley Park

in April or May 1899. Darvarich said they flew at a height of 20 to 25 ft (6.1 to 7.6 m) in a steam-powered

monoplane

aircraft and crashed into a three-story

building. Darvarich said he was stoking the boiler aboard the craft and was badly scalded in the accident, requiring several weeks in a hospital. Reportedly because of this incident, Whitehead was forbidden by the police to do any more flight experiments in Pittsburgh.

Whitehead and Darvarich traveled to Bridgeport, Connecticut

to find factory jobs.

, Connecticut on 14 August 1901. According to an eyewitness newspaper article (widely attributed to journalist Dick Howell of the Bridgeport Sunday Herald although Howell never claimed it as his), Whitehead piloted his Number 21 aircraft in a controlled powered flight for about half a mile up to 50 feet (15.2 m) high and landed safely.A photocopy of the article is available: Photocopy of Bridgeport Sunday Herald, August 18, 1901 The feat, if true, preceded the Wright brothers

by more than two years and exceeded their best 1903 Kitty Hawk

flight, which covered 852 feet (259.7 m) at a height of about 10 feet (3 m).

The Sunday Herald article was published on 18 August 1901. Information from the article was also reprinted in the New York Herald

and Boston Transcript. No photographs were taken. A drawing of the aircraft flying accompanied the Sunday Herald article.

The article said Whitehead and another man drove to the testing area in the machine, which worked like a car when the wings were folded along its sides. Two other people, including the newspaper reporter, followed on bicycles. For short distances the Number 21's speed was close to thirty miles an hour on the uneven road, and the article said, "There seems no doubt that the machine can reel off forty miles an hour and not exert the engine to its fullest capacity.".

The article said Whitehead and another man drove to the testing area in the machine, which worked like a car when the wings were folded along its sides. Two other people, including the newspaper reporter, followed on bicycles. For short distances the Number 21's speed was close to thirty miles an hour on the uneven road, and the article said, "There seems no doubt that the machine can reel off forty miles an hour and not exert the engine to its fullest capacity.".

The Sunday Herald reported that before attempting to pilot the aircraft, Whitehead successfully test flew it unmanned in the pre-dawn hours, using tether ropes and sandbag

ballast. When Whitehead was ready to make a manned flight, the article said: "By this time the light was good. Faint traces of the rising sun began to suggest themselves in the east."

The newspaper reported that trees blocked the way after the flight was in progress, and quoted Whitehead as saying, "I knew that I could not clear them by rising higher, and also that I had no means of steering around them by using the machinery." The article said Whitehead quickly thought of a solution to steer around the trees:

When Whitehead neared the end of a field, the article said he turned off the motor and the aircraft landed "so lightly that Whitehead was not jarred in the least."

When Whitehead neared the end of a field, the article said he turned off the motor and the aircraft landed "so lightly that Whitehead was not jarred in the least."

Junius Harworth, who was a boy when he was one of Whitehead's helpers, said Whitehead flew the airplane at another time in the summer of 1901 from Howard Avenue East to Wordin Avenue, along the edge of property belonging to the local gas company. Upon landing, Harworth said, the machine was turned around and another hop was made back to the starting point.

During this period of activity, Whitehead also reportedly tested an unmanned and unpowered flying machine, towed by men pulling ropes. A witness said the craft rose above telephone lines, flew across a road and landed undamaged. The distance covered was later measured at approximately 1,000 ft (305 m).

(30 kilowatt

) motor instead of the 20 hp (15 kW) used in the Number 21, and aluminum instead of bamboo

for structural components. In two published letters he wrote to American Inventor magazine, Whitehead said the flights took place over Long Island Sound

. He said the distance of the first flight was about two miles (3 kilometers) and the second was seven miles (11 km) in a circle at heights up to 200 ft (61 m). He said the airplane, which had a boat-like fuselage

, landed safely in the water near the shore.

For steering, Whitehead said he varied the speed of the two propellers and also used the aircraft rudder. He said the techniques worked well on his second flight and enabled him to fly a big circle back to the shore where his helpers waited. He expressed pride in the accomplishment: "...as I successfully returned to my starting place with a machine hitherto untried and heavier than air, I consider the trip quite a success. To my knowledge it is the first of its kind. This matter has so far never been published."

In his first letter to American Inventor, Whitehead said, "This coming Spring I will have photographs made of Machine No. 22 in the air." He said snapshots, apparently taken during his claimed flights of 17 January 1902 "did not come out right" because of cloudy and rainy weather. The magazine editor replied that he and readers would "await with interest the promised photographs of the machine in the air," but there were no further letters nor any photographs from Whitehead.

A description of a Whitehead aircraft as remembered 33 years later by his brother John Whitehead gave information related to steering:

John Whitehead arrived in Connecticut from California in April 1902, intending to help his brother. He did not see any of his brother's aircraft in powered flight.

A 1935 article in Popular Aviation magazine, which renewed interest in Whitehead, said winter weather ruined the Number 22 airplane after Whitehead placed it unprotected in his yard following his claimed flights of January 1902. The article said Whitehead did not have money to build a shelter for the aircraft because of a quarrel with his financial backer. The article also reported that in early 1903 Whitehead built a 200 horsepower eight-cylinder engine, intended to power a new aircraft. Another financial backer insisted on testing the engine in a boat on Long Island Sound, but lost control and capsized, sending the engine to the bottom.

The engine shown in the September 1903 article was the engine exhibited by Whitehead at the Second Annual Exhibit of the Aero Club of America in December 1906 that was shown in the photo between the Curtiss and Wright engines.

Whitehead's Number 21 monoplane had a wingspan of 36 ft (11 m). The fabric covered wing

Whitehead's Number 21 monoplane had a wingspan of 36 ft (11 m). The fabric covered wing

s were ribbed with bamboo, supported by steel

wires and were very similar to the shape of the Lilienthal glider's wings. The arrangement for folding the wings also closely followed the Lilienthal design. The craft was powered by two engines: a ground engine of 10 hp (7.5 kW), intended to propel the front wheels to reach takeoff

speed, and a 20 hp (15 kW) acetylene engine powering two propellers, which were designed to counter-rotate

for stability.

Whitehead owned and read a copy of Octave Chanute

's famed 1894 "Progress in Flying Machines." Chanute detailed Count D'Esterno's design, along with a top view drawing of the machine, which was not built. The design of Whitehead's No. 21 1899–1901 monoplane shared many important features with the design of D'Esterno's 1864 monoplane glider and Penaud and Gauchot's 1876 monoplane.

Whitehead described his No. 22 aircraft and compared some of its features to the No. 21 in a letter he wrote to the editor of American Inventor magazine, published 1 April 1902. He said the No. 22 had a five-cylinder 40 hp kerosene

motor of his own design, weighing 120 lbs. He said ignition was "accomplished by its own heat and compression." He described the aircraft as 16 feet (4.9 m) long, made mostly of steel and aluminum with wing ribs made of steel tubing, rather than bamboo, which was used in the Number 21 aircraft. He explained that the two front wheels were connected to the kerosene motor, and the rear wheels were used for steering while on the ground. He said the wing area was 450 square feet (41.8 m²), and the covering was "the best silk obtainable." The propellers were "6 feet in diameter...made of wood...covered with very thin aluminum sheeting." He said the tail and wings could all be "folded up...and laid against the sides of the body."

Whitehead also built gliders until about 1906 and was photographed flying them.

wrote: "In fact, Weisskopf's ability and mechanical skill could have made him a wealthy man at a time when there was an ever-increasing demand for lightweight engines, but he was far more interested in flying." Instead, Whitehead only accepted enough engine orders to sustain aviation experiments.

Whitehead's business practices were unsophisticated and he was sued by a customer, resulting in a threat that his tools and equipment would be seized. He hid his engines and most of his tools in a neighbor's cellar and continued his aviation work. One of his engines was installed by aviation pioneer Charles Wittemann

in a helicopter built by Lee Burridge of the Aero Club of America, but the craft failed to fly.

Whitehead's own 1911 studies of the vertical flight problem resulted in a 60-bladed helicopter, which, unmanned, lifted itself off the ground.

He lost an eye in a factory accident and also suffered a severe blow to the chest from a piece of factory equipment, an injury that may have led to increasing attacks of angina. Despite these setbacks he exhibited an aircraft at Hempstead, New York, as late as 1915. He continued to work and invent. He designed a braking safety device, hoping to win a prize offered by a railroad. He demonstrated it as a scale model but won nothing. He constructed an "automatic" concrete-laying machine, which he used to help build a road north of Bridgeport. These inventions, however, brought him no more profit than did his airplanes and engines. Around 1915 Whitehead worked in a factory as laborer and repaired motors to support his family.

With World War I

came prejudice against Germans. Whitehead never lost his German accent and never acquired American citizenship

.

He died of a massive heart attack

, on 10 October 1927, after attempting to lift an engine out of an automobile he was repairing. He stumbled onto his front porch and into his home, then collapsed dead in the house.

buff Harvey Phillips. Randolph expanded the article into a book, "Lost Flights of Gustave Whitehead," published in 1937. Randolph sought out people who had known Whitehead and had seen his flying machines and engines. She obtained 16 affidavits from 14 people and included the text of their statements in the book. Four people said they did not see flights, while the others said they saw flights of various types, ranging from a few dozen to hundreds of feet to more than a mile.

Harvard University

economics professor John B. Crane wrote an article published in National Aeronautic Magazine in December 1936, disputing claims and reports that Whitehead flew. The following year, after further research, Crane adopted a different tone. He told reporters, "There are several people still living in Bridgeport who testified to me under oath they had seen Whitehead make flights along the streets of Bridgeport in the early 1900s." Crane repeated Harworth's claim of having witnessed a one-and-a-half mile airplane flight made by Whitehead on 14 August 1901. He suggested a Congressional investigation to consider the claims.

In 1949 Crane published a new article in Air Affairs magazine that supported claims that Whitehead flew.

In 1963 William O'Dwyer, a reserve U.S. Air Force major, accidentally discovered photographs of a 1910 Whitehead "Large Albatross"-type biplane aircraft shown at rest on the ground, the collection found in the attic of a Connecticut house. He then devoted himself to researching Whitehead and became convinced he had made powered flights before the Wright brothers. O'Dwyer contributed to a second book by Stella Randolph, The Story of Gustave Whitehead, Before the Wrights Flew, published in 1966. They co-authored another book, History by Contract

, published in 1978, which criticized the Smithsonian Institution

for inadequately investigating claims that Whitehead flew.

In 1968, Connecticut officially recognized Whitehead as "Father of Connecticut Aviation". Seventeen years later, the North Carolina General Assembly

passed a resolution which repudiated the Connecticut statement and gave "no credence" to the assertion that Whitehead was first to fly, citing "leading aviation historians and the world's largest aviation museum" who determined there was "no historic fact, documentation, record or research to support the claim".

Decades later, Dickie denied seeing a flight. He said in a 1937 affidavit taken during Stella Randolph's research that he was not present at the reported flight on 14 August 1901, that he did not know Andrew Cellie, the other associate of Whitehead who was supposed to be there, and that none of Whitehead's aircraft ever flew, to the best of his knowledge.

Dickie said he did not believe that an airplane in photographs that were shown to him ever flew. An article in Air Enthusiast countered by saying that the description Dickie gave of the airplane did not match Whitehead's Number 21.

O'Dwyer had known the older Dickie since childhood. Early in his research, O'Dwyer spoke by telephone to Dickie. O'Dwyer learned that Dickie had a grudge against Whitehead. O'Dwyer described the conversation:

O'Dwyer said he thought Dickie's 1937 affidavit had "little value." He said there were inconsistencies between the affidavit and his interview with Dickie.

The other man who the Sunday Herald said was an eyewitness to the reported flight on 14 August 1901 was believed to be Andrew Cellie, but he could not be found in the 1930s when Randolph investigated. O'Dwyer said that in the 1970s he searched through old Bridgeport city directories and concluded that the newspaper misspelled the man's name, which was actually Andrew Suelli, who was a Swiss or German immigrant also known as Zulli, and was Whitehead's next door neighbor before moving to the Pittsburgh area in 1902. Cellie's former neighbors in Fairfield told O'Dwyer that Cellie, who died before O'Dwyer investigated, had "always claimed he was present when Whitehead flew in 1901."

Junius Harworth and Anton Pruckner, who sometimes helped or worked for Whitehead, gave statements decades later as part of Stella Randolph's research, claiming they saw Whitehead fly on 14 August 1901.

Anton Pruckner, a tool maker who worked a few years with Whitehead, attested in 1934 to the flight. He also attested to a January 1902 flight by Whitehead over Long Island Sound, but the 1988 Air Enthusiast article said "Pruckner was not present on the occasion, though he was told of the events by Weisskopf himself."

In his first letter to American Inventor, Whitehead claimed he made four "trips" in the airplane on 14 August 1901; and that the longest was one and a half miles.

Discrepancies in statements by witnesses about different flights they said they saw on 14 August 1901, raised questions whether any flight was made. The Bridgeport Sunday Herald reported a half mile flight occurred early in the morning on 14 August. Whitehead and Harworth later claimed that a flight one and a half miles long was made that day.

Among the affidavits collected by Stella Randolph are these, quoted in part:

O'Dwyer organized a survey of surviving witnesses to the reported Whitehead flights. Members of the Connecticut Aeronautical Historical Association (CAHA) and the 9315th Squadron (O'Dwyer's U.S. Air Force Reserve unit) went door-to-door in Bridgeport, Fairfield, Stratford, and Milford, Connecticut to track down Whitehead's long-ago neighbors and helpers. They also traced some who had moved to other parts of the state and the U.S. Of an estimated 30 persons interviewed for affidavits or on tape, 20 said they had seen flights, eight indicated they had heard of the flights, and two said that Whitehead did not fly.

Photographs have not been found showing any of Whitehead's airplanes in flight. According to William O'Dwyer, the Bridgeport Daily Standard newspaper reported that photos showing Gustave Whitehead in successful powered flight did exist and were exhibited in the window of Lyon and Grumman Hardware store on Main Street, Bridgeport, Connecticut in October 1903.

Photographs have not been found showing any of Whitehead's airplanes in flight. According to William O'Dwyer, the Bridgeport Daily Standard newspaper reported that photos showing Gustave Whitehead in successful powered flight did exist and were exhibited in the window of Lyon and Grumman Hardware store on Main Street, Bridgeport, Connecticut in October 1903.

Another missing photo that purportedly showed a Whitehead aircraft in flight was displayed in the 1906 First Annual Exhibit of the Aero Club of America at the 69th Regiment Armory

in New York City. The photo was mentioned in a 27 January 1906 Scientific American

magazine article. The article said the walls of the exhibit room were covered with a large collection of photographs showing the machines of inventors such as Whitehead, Henry Berliner

and Alberto Santos-Dumont

. Other photographs showed airships and balloons in flight. The report said a single blurred photograph of a large birdlike machine propelled by compressed air constructed by Whitehead in 1901 was the only other photograph besides that of Samuel Pierpont Langley

's scale model

machines of a motor-driven aeroplane in successful flight. In 1986, Peter L. Jakab, National Air and Space Museum

(NASM) Associate Director and Curator of Early Flight, wrote that the image "may very well have been an in-flight photograph" of one of Whitehead's gliders.

Two Connecticut Whitehead fans said they heard about yet another photograph: high school science teacher and pilot Andy Kosch, and Connecticut State Senator George Gunther

. They were told that a sea captain named Brown made a logbook entry about Whitehead flying over Long Island Sound and even photographed the airplane in flight. A friend told Kosch he found the captain's leather-bound journal containing a photo of Whitehead in flight and a description of the event. After some difficulty, Kosch made contact with the owners of the journal, but they told him it was lost.

In 1986, American actor and accomplished aviator Cliff Robertson

, was contacted by the Hangar 21 group in Bridgeport and was asked to attempt to fly their reproduction No.21 while under tow behind a sports car, for the benefit of the press. Robertson said "We did a run and nothing happened. And we did a second run and nothing happened. Then the wind came up a little and we did another run and, sure enough, I got her up and flying. Then we went back and did a second one." Robertson commented, "We will never take away the rightful role of the Wright Brothers, but if this poor little German immigrant did indeed get an airplane to go up and fly one day, then let's give him the recognition he deserves."

On 18 February 1998 another reproduction of No. 21 was flown 500 m (1,640.4 ft) in Germany.

O'Dwyer believed that Howell made the drawing of the No. 21 in flight, saying that Howell was "an artist before he became a reporter."

O'Dwyer spent hours in the Bridgeport Library studying virtually everything Howell wrote. O'Dwyer said: "Howell was always a very serious writer. He always used sketches rather than photographs with his features on inventions. He was highly regarded by his peers on other local newspapers. He used the florid style of the day, but was not one to exaggerate. Howell later became the Herald

Kosch said, "If you look at the reputation of the editor of the Bridgeport Herald in those days, you find that he was a reputable man. He wouldn't make this stuff up." Howell died before the controversy about Whitehead began.

The Sunday Herald article was published 18 August 1901, four days after the event it described. According to Aviation History, Whitehead detractors, including Orville Wright, used the delay in publication to cast doubt on the story, questioning why the newspaper would wait four days before reporting such important news. Orville Wright's critical comments were later quoted by the both the Smithsonian Institution and by British aviation historian Charles Harvard Gibbs-Smith

. Aviation History explained that the Bridgeport Sunday Herald was a weekly newspaper published only on Sundays.

As to whether Whitehead's wife resented matters, Stella Randolph wrote "Mrs. Whitehead talked very freely and frankly with the writer, who made several visits to her home, in the 1930s, and there was never any intimation that she harbored any resentment about the past."

Smithsonian Institution Curator of Aeronautics Peter L. Jakab said that Whitehead's wife and family did not know about his August 1901 flights.

Beach claimed authorship of only one Scientific American article about Whitehead, that of 8 June 1901, a few weeks before the report in the Bridgeport Sunday Herald. The Scientific American article by Beech described Whitehead's machine as a "novel flying machine." Two photographs were included of a "batlike" craft.". The article did not state Whitehead had flown and was published before Whitehead's reported flight of 14 August 1901. Unsigned articles in Scientific American in 1906 and 1908 did state that Whitehead had flown in 1901, but gave no details.

O'Dwyer asserted that all the articles in Scientific American which mentioned Whitehead had been written by Beach, but did not offer proof. O'Dwyer thus believed that, because of a statement Beach made many years later, Beach had "recanted" his earlier view that Whitehead had flown. O’Dwyer supported his opinion by asserting that Beach became a "politician" who was "rarely missing an opportunity to mingle with the Wright tide that had turned against Whitehead, notably after Whitehead's death in 1927."

In 1939 Beach wrote down his thoughts about Whitehead, stating, "I do not believe that any of his machines ever left the ground under their own power in spite of the assertions of many persons who think they saw him fly."

Beach stated that Whitehead "deserves a place in early aviation, due to his having gone ahead and built extremely light engines and aeroplanes. The five-cylinder kerosene one, with which he claims to have flown over Long Island Sound on 17 January 1902 was, I believe, the first aviation Diesel."

. Smithsonian Secretary Samuel Langley at that time was building his manned aircraft, the Large Aerodrome "A"

. In September 1901, Langley's chief engineer, Charles M. Manly, requested that F.W. Hodge, a staff clerk, look over Whitehead's Number 21 aircraft, then on public display in Atlantic City, New Jersey, where Hodge was staying. Manly asked Hodge to estimate the dimensions of the wings, tail and propellers, the mechanism of the propeller drive and the nature of the construction, which Manly thought might be too weak. The item Manly stated he was "more interested in than anything else" was the acetylene engine. Manly stated he believed the claims made for the machine were "fraudulent." Hodge reported the machine did not appear to be airworthy.

In 1903 two attempts to achieve manned, powered flight with Langley's Aerodrome failed completely. When the Wright brothers' flights became well known, the Smithsonian Institution tried to diminish their achievement and advance those of Langley. The Wrights offered their Flyer

to the Smithsonian in 1910 but were rebuffed by the Institution. Instead, the Smithsonian gave aviator Glenn Curtiss

permission to rebuild Langley's failed aircraft, an effort which included major but unpublicized design improvements. Curtiss and his team made several brief manned flights with the rebuilt Aerodrome in 1914. The Smithsonian took this as proof that Langley had created the first heavier than air machine "capable" of manned flight. Insulted by this development, Orville Wright lent the Flyer to the Science Museum

in London, an act which eventually turned public opinion against the Smithsonian. When the Flyer was finally brought back and presented to the Smithsonian in 1948, the museum and the executors of the Wright estate signed an agreement (popularly called a "contract") in which the Smithsonian promised not to say that any airplane before the Wrights' was capable of manned, powered, controlled flight.Image of the agreement is on this archived page of the "glennhcurtiss.com" website. The Agreement is also available upon request from the National Air and Space Museum of the Smithsonian Institution. This agreement was not made public.

In 1975, O'Dwyer learned about the agreement from Harold S. Miller, an executor of the Wright estate. According to Aviation History, O'Dwyer pursued the matter and obtained release of the document, with help from Connecticut U.S. Senator Lowell Weicker and the U.S. Freedom of Information Act. O'Dwyer said that during an earlier 1969 conversation with Paul E. Garber

, a Smithsonian expert on early aircraft, Garber denied that a contract existed and said he "could never agree to such a thing."

History by Contract, the book co-authored by O'Dwyer and Randolph, argued that the agreement unfairly suppressed recognition of Whitehead's achievements. However, the agreement contained no mention of Whitehead and was implemented only to settle the long-running feud between the Wrights and the Smithsonian regarding its false claims for the Aerodrome.

In July 2005, Peter Jakab of the Smithsonian's National Air and Space Museum and said the agreement with the Wright estate would not stop the Smithsonian from recognizing anyone as the inventor of the first airplane if indisputable evidence was found:

Former Connecticut State Senator George Gunther said O'Dwyer's book History by Contract was too heavy-handed. Gunther said he had been having "cordial" conversations with the Smithsonian about giving credit to Whitehead, "but after O'Dwyer blasted them in his book, well, that totally turned them off."

O'Dwyer learned the Smithsonian had published a Bibliography of Aeronautics in 1909 which included references to Whitehead. O'Dwyer said it was "hard to understand" why the Smithsonian never contacted Whitehead or his family to learn more about the flight claims.

An article titled "Did Whitehead Fly?" in the January 1988 edition of Air Enthusiast magazine took an accusatory tone toward the Smithsonian: "The evidence amassed in his favour strongly indicates that, beyond reasonable doubt, the first fully controlled, powered flight that was more than a test 'hop', witnessed by a member of the press, took place on 14 August 1901 near Bridgeport, Connecticut. For this assertion to be conclusively disproved, the Smithsonian must do much more than pronounce him a hoax while wilfully turning a blind eye to all the affidavits, letters, tape recorded interviews and newspaper clippings which attest to Weisskopf's genius." The writer was Georg K. Weissenborn, a professor of German language at the University of Toronto

. He was in communication with O'Dwyer before and after the article's publication.

In a letter to Wilbur Wright on 3 July 1901, Chanute made a single reference to Whitehead, saying: "I have a letter from Carl E. Myers, the balloon maker, stating that a Mr. Whitehead has invented a light weight motor, and has engaged to build for Mr. Arnot of Elmira 'a motor of 10 I.H.P....'" No letter has been found addressed from the Wright brothers to Whitehead dating from before they first flew in 1903.

Statements obtained by Stella Randolph in the 1930s from two of Whitehead's workers, Cecil Steeves and Anton Pruckner, claimed that the Wright brothers visited Whitehead's shop a year or two before their 1903 flight. The January 1988 Air Enthusiast magazine states: "Both Cecil Steeves and Junius Harworth remember the Wrights; Steeves described them and recalled their telling Weisskopf that they had received his letter indicating an exchange of correspondence." Steeves said that the Wright brothers, "under the guise of offering to help finance his inventions, actually received inside information that aided them materially in completing their own plane." Steeves related that Whitehead said to him, "Now since I have given them the secrets of my invention they will probably never do anything in the way of financing me."

Orville Wright denied that he or his brother ever visited Whitehead at his shop and stated that the first time they were in Bridgeport was 1909 "and then only in passing through on the train." This position is supported by Library of Congress

historian Fred Howard, co-editor of the Wright brothers' papers, and by aviation writers Martin Caidin

and Harry Combs.

In 1945 Whitehead's son Charles was interviewed on a national radio program as the son of the first man to fly. That claim was highlighted in a magazine article, which was condensed in a Reader's Digest

article that reached a very large audience. Orville Wright, then in his seventies, countered by writing an article, "The Mythical Whitehead Flight", which appeared in the August 1945 issue of U.S. Air Services, a publication with a far smaller, but very influential, readership. Wright listed several reasons for disbelieving Whitehead, then quoted John J. Dvorak, professor of Physics at Washington University in St. Louis

, who had financed Whitehead in 1904 but rejected his flight claims in 1936. Dvorak said, "I personally do not believe that Whitehead ever succeeded in making any airplane flights. Here are my reasons: 1. Whitehead did not possess sufficient mechanical skill and equipment to build a successful motor. 2. Whitehead was given to gross exaggeration. He was eccentric—a visionary and a dreamer to such an extent that he actually believed what he merely imagined. He had delusions." This was a reversal of Dvorak's original opinion about Whitehead's competence. When he worked with Whitehead, Dvorak reportedly believed that Whitehead "was more advanced with the development of aircraft than other persons who were engaged in the work."

In the 1950s British aviation historian and author Charles Harvard Gibbs-Smith studied The Papers of Wilbur and Orville Wright at the Library of Congress

, and Randolph's 1937 book, and concluded that reports of Whitehead making a successful flight in advance of the Wright brothers were fabrications. Gibbs-Smith wrote: "Unfortunately, some of those who advanced [Whitehead's] claims were more intent on discrediting the Wright brothers than on establishing facts." He said in 1960 that no "reputable" aviation historian believes Whitehead ever flew.

Interest in Whitehead's engines is also indicated by recollections of his daughter Rose, who said her father received numerous orders for them and even declined as many as 50 orders in a single day because he was too busy.

An online biography based on the O'Dwyer and Randolph books asserts that the engine Whitehead purportedly used in Pittsburgh attracted the attention of Australia

n aeronautical pioneer, Lawrence Hargrave

, who in 1889 invented a rotary engine: "This steam machine was so ingenious that several years later Lawrence Hargrave told of using miniature designs of "Weisskopf-style" steam machines, as well as the "Weisskopf System" for his model trials in Australia."

Contemporary U.S. aviation researchers Nick Engler and Louis Chmiel dismiss Whitehead's work and its influence, even if new evidence is discovered showing that he flew before the Wright brothers:

Whitehead expressed his own dedication to heavier-than-air flight in a letter to American Inventor magazine in 1902. He wrote that because "the future of the air machine lies in an apparatus made without the gas bag, I have taken up the aeroplane and will stick to it until I have succeeded completely or expire in the attempt of so doing." Newspapers around the world had reported about Santos-Dumont's experiments with motorized and steerable gas bags for a few years when Whitehead wrote this.

In the decades since, several non-academic researchersThe researchers include Stella Randolph, William O'Dwyer and Andy Kosch. A German museum also makes the assertion. have promoted their belief that Whitehead made controlled, powered airplane flights more than two years before the Wright Brothers

Wright brothers

The Wright brothers, Orville and Wilbur , were two Americans credited with inventing and building the world's first successful airplane and making the first controlled, powered and sustained heavier-than-air human flight, on December 17, 1903...

did on 17 December 1903. These claims have repeatedly been dismissed by mainstream aviation scholars.The mainstream scholars and historians include Charles Harvard Gibbs-Smith, William F. Trimble, Tom D. Crouch, Fred Howard, and Walter J. Boyne.

Claims for Whitehead rest largely on a long local newspaper article that said he made a powered controlled flight in Connecticut in August 1901. He personally claimed credit for the feat, and he and eyewitnesses said he made several other powered flights in 1901 and 1902. Scientific American magazine published an article in September 1903 about Whitehead making motorized flights in a triplane originally designed as a glider. After 1903 publicity faded for his aeronautical efforts, which lasted from about 1897 to 1911. He lapsed into obscurity until his name was brought back to public attention by a 1935 magazine article and a 1937 book which focused attention on his life and work and led to "lively debate" among scholars, researchers, aviation enthusiasts and even Orville Wright on the question of whether Whitehead actually flew. Research in the 1960s and 70s, and pro-Whitehead books in 1966 and 1978 led to renewed examination and dismissal of the claims by aviation scholars. Since the 1980s enthusiasts in the U.S. and Germany have built working replicas of Whitehead's 1901 flying machine. Some of the replicas were built as towed gliders, while the powered ones utilized modern engines and propellers.

Early life and career

Leutershausen

Leutershausen is a municipality in the district of Ansbach, in Bavaria, Germany. It is situated on the river Altmühl, 12 km west of Ansbach.-History:...

, Bavaria

Bavaria

Bavaria, formally the Free State of Bavaria is a state of Germany, located in the southeast of Germany. With an area of , it is the largest state by area, forming almost 20% of the total land area of Germany...

, the second child of Karl Weisskopf and his wife Babetta. As a boy, he showed an interest in flight, experimenting with kite

Kite

A kite is a tethered aircraft. The necessary lift that makes the kite wing fly is generated when air flows over and under the kite's wing, producing low pressure above the wing and high pressure below it. This deflection also generates horizontal drag along the direction of the wind...

s and earning the nickname "the flyer". He and a friend caught and tethered bird

Bird

Birds are feathered, winged, bipedal, endothermic , egg-laying, vertebrate animals. Around 10,000 living species and 188 families makes them the most speciose class of tetrapod vertebrates. They inhabit ecosystems across the globe, from the Arctic to the Antarctic. Extant birds range in size from...

s in an attempt to learn how they flew, an activity which police soon stopped. His parents died in 1886 and 1887, when he was a boy. He then trained as a mechanic and traveled to Hamburg

Hamburg

-History:The first historic name for the city was, according to Claudius Ptolemy's reports, Treva.But the city takes its modern name, Hamburg, from the first permanent building on the site, a castle whose construction was ordered by the Emperor Charlemagne in AD 808...

, where in 1888 he was forced to join the crew of a sailing ship. A year later, he returned to Germany, then journeyed with a family to Brazil

Brazil

Brazil , officially the Federative Republic of Brazil , is the largest country in South America. It is the world's fifth largest country, both by geographical area and by population with over 192 million people...

. He went to sea again for several years, learning more about wind, weather and bird flight.

Weisskopf arrived in the U.S. in 1893. He soon anglicized his name to Gustave Whitehead. In 1897 the Aeronautical Club of Boston hired Whitehead to build two gliders, one of which (patterned after a Lilienthal glider) was partially successful and in which Whitehead flew short distances, and toy manufacturer E. J. Horsman in New York hired Whitehead to build and operate advertising kites, and model gliders. Whitehead occupied himself with plans to provide a motor to drive one of his gliders.

Pittsburgh 1899

According to an affidavit given in 1934 by Louis Darvarich, a friend of Whitehead, the two men made a motorized flight together of about half a mile in PittsburghPittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Pittsburgh is the second-largest city in the US Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and the county seat of Allegheny County. Regionally, it anchors the largest urban area of Appalachia and the Ohio River Valley, and nationally, it is the 22nd-largest urban area in the United States...

's Schenley Park

Schenley Park

Schenley Park is a large municipal park located in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, between the neighborhoods of Oakland, Greenfield, and Squirrel Hill. It is also listed on the National Register of Historic Places as a historic district...

in April or May 1899. Darvarich said they flew at a height of 20 to 25 ft (6.1 to 7.6 m) in a steam-powered

Steam engine

A steam engine is a heat engine that performs mechanical work using steam as its working fluid.Steam engines are external combustion engines, where the working fluid is separate from the combustion products. Non-combustion heat sources such as solar power, nuclear power or geothermal energy may be...

monoplane

Monoplane

A monoplane is a fixed-wing aircraft with one main set of wing surfaces, in contrast to a biplane or triplane. Since the late 1930s it has been the most common form for a fixed wing aircraft.-Types of monoplane:...

aircraft and crashed into a three-story

Storey

A storey or story is any level part of a building that could be used by people...

building. Darvarich said he was stoking the boiler aboard the craft and was badly scalded in the accident, requiring several weeks in a hospital. Reportedly because of this incident, Whitehead was forbidden by the police to do any more flight experiments in Pittsburgh.

Whitehead and Darvarich traveled to Bridgeport, Connecticut

Bridgeport, Connecticut

Bridgeport is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Connecticut. Located in Fairfield County, the city had an estimated population of 144,229 at the 2010 United States Census and is the core of the Greater Bridgeport area...

to find factory jobs.

Connecticut 1901

The aviation event for which Whitehead is now best-known reportedly took place in FairfieldFairfield, Connecticut

Fairfield is a town located in Fairfield County, Connecticut, United States. It is bordered by the towns of Bridgeport, Trumbull, Easton, Redding and Westport along the Gold Coast of Connecticut. As of the 2010 census, the town had a population of 59,404...

, Connecticut on 14 August 1901. According to an eyewitness newspaper article (widely attributed to journalist Dick Howell of the Bridgeport Sunday Herald although Howell never claimed it as his), Whitehead piloted his Number 21 aircraft in a controlled powered flight for about half a mile up to 50 feet (15.2 m) high and landed safely.A photocopy of the article is available: Photocopy of Bridgeport Sunday Herald, August 18, 1901 The feat, if true, preceded the Wright brothers

Wright brothers

The Wright brothers, Orville and Wilbur , were two Americans credited with inventing and building the world's first successful airplane and making the first controlled, powered and sustained heavier-than-air human flight, on December 17, 1903...

by more than two years and exceeded their best 1903 Kitty Hawk

Kitty Hawk, North Carolina

Kitty Hawk is a town in Dare County, North Carolina, United States. The population was 3,000 at the 2000 census. It was established in the early 18th century as Chickahawk....

flight, which covered 852 feet (259.7 m) at a height of about 10 feet (3 m).

The Sunday Herald article was published on 18 August 1901. Information from the article was also reprinted in the New York Herald

New York Herald

The New York Herald was a large distribution newspaper based in New York City that existed between May 6, 1835, and 1924.-History:The first issue of the paper was published by James Gordon Bennett, Sr., on May 6, 1835. By 1845 it was the most popular and profitable daily newspaper in the UnitedStates...

and Boston Transcript. No photographs were taken. A drawing of the aircraft flying accompanied the Sunday Herald article.

The Sunday Herald reported that before attempting to pilot the aircraft, Whitehead successfully test flew it unmanned in the pre-dawn hours, using tether ropes and sandbag

Sandbag

A sandbag is a sack made of hessian/burlap, polypropylene or other materials that is filled with sand or soil and used for such purposes as flood control, military fortification, shielding glass windows in war zones and ballast....

ballast. When Whitehead was ready to make a manned flight, the article said: "By this time the light was good. Faint traces of the rising sun began to suggest themselves in the east."

The newspaper reported that trees blocked the way after the flight was in progress, and quoted Whitehead as saying, "I knew that I could not clear them by rising higher, and also that I had no means of steering around them by using the machinery." The article said Whitehead quickly thought of a solution to steer around the trees:

"He simply shifted his weight more to one side than the other. This careened the ship to one side. She turned her nose away from the clump of sprouts when within fifty yards of them and took her course around them as prettily as a yacht on the sea avoids a barShoalShoal, shoals or shoaling may mean:* Shoal, a sandbank or reef creating shallow water, especially where it forms a hazard to shipping* Shoal draught , of a boat with shallow draught which can pass over some shoals: see Draft...

. The ability to control the air ship in this manner appeared to give Whitehead confidence, for he was seen to take time to look at the landscape about him. He looked back and waved his hand exclaiming, 'I've got it at last.'"

Junius Harworth, who was a boy when he was one of Whitehead's helpers, said Whitehead flew the airplane at another time in the summer of 1901 from Howard Avenue East to Wordin Avenue, along the edge of property belonging to the local gas company. Upon landing, Harworth said, the machine was turned around and another hop was made back to the starting point.

During this period of activity, Whitehead also reportedly tested an unmanned and unpowered flying machine, towed by men pulling ropes. A witness said the craft rose above telephone lines, flew across a road and landed undamaged. The distance covered was later measured at approximately 1,000 ft (305 m).

Connecticut 1902

Whitehead claimed two spectacular flights on 17 January 1902 in his improved Number 22, with a 40 HorsepowerHorsepower

Horsepower is the name of several units of measurement of power. The most common definitions equal between 735.5 and 750 watts.Horsepower was originally defined to compare the output of steam engines with the power of draft horses in continuous operation. The unit was widely adopted to measure the...

(30 kilowatt

Watt

The watt is a derived unit of power in the International System of Units , named after the Scottish engineer James Watt . The unit, defined as one joule per second, measures the rate of energy conversion.-Definition:...

) motor instead of the 20 hp (15 kW) used in the Number 21, and aluminum instead of bamboo

Bamboo

Bamboo is a group of perennial evergreens in the true grass family Poaceae, subfamily Bambusoideae, tribe Bambuseae. Giant bamboos are the largest members of the grass family....

for structural components. In two published letters he wrote to American Inventor magazine, Whitehead said the flights took place over Long Island Sound

Long Island Sound

Long Island Sound is an estuary of the Atlantic Ocean, located in the United States between Connecticut to the north and Long Island, New York to the south. The mouth of the Connecticut River at Old Saybrook, Connecticut, empties into the sound. On its western end the sound is bounded by the Bronx...

. He said the distance of the first flight was about two miles (3 kilometers) and the second was seven miles (11 km) in a circle at heights up to 200 ft (61 m). He said the airplane, which had a boat-like fuselage

Fuselage

The fuselage is an aircraft's main body section that holds crew and passengers or cargo. In single-engine aircraft it will usually contain an engine, although in some amphibious aircraft the single engine is mounted on a pylon attached to the fuselage which in turn is used as a floating hull...

, landed safely in the water near the shore.

For steering, Whitehead said he varied the speed of the two propellers and also used the aircraft rudder. He said the techniques worked well on his second flight and enabled him to fly a big circle back to the shore where his helpers waited. He expressed pride in the accomplishment: "...as I successfully returned to my starting place with a machine hitherto untried and heavier than air, I consider the trip quite a success. To my knowledge it is the first of its kind. This matter has so far never been published."

In his first letter to American Inventor, Whitehead said, "This coming Spring I will have photographs made of Machine No. 22 in the air." He said snapshots, apparently taken during his claimed flights of 17 January 1902 "did not come out right" because of cloudy and rainy weather. The magazine editor replied that he and readers would "await with interest the promised photographs of the machine in the air," but there were no further letters nor any photographs from Whitehead.

A description of a Whitehead aircraft as remembered 33 years later by his brother John Whitehead gave information related to steering:

"Rudder was a combination of horizontal and vertical fin-like affair, the principle the same as in the up-to-date airplanes. For steering there was a rope from one of the foremost wing tip ribs to the opposite, running over a pulley. In front of the operator was a lever connected to a pulley: the same pulley also controlled the tail rudder at the same time."

John Whitehead arrived in Connecticut from California in April 1902, intending to help his brother. He did not see any of his brother's aircraft in powered flight.

A 1935 article in Popular Aviation magazine, which renewed interest in Whitehead, said winter weather ruined the Number 22 airplane after Whitehead placed it unprotected in his yard following his claimed flights of January 1902. The article said Whitehead did not have money to build a shelter for the aircraft because of a quarrel with his financial backer. The article also reported that in early 1903 Whitehead built a 200 horsepower eight-cylinder engine, intended to power a new aircraft. Another financial backer insisted on testing the engine in a boat on Long Island Sound, but lost control and capsized, sending the engine to the bottom.

1903

A full-page article in the 19 September 1903 Scientific American told of Whitehead making powered flights in what had been his triplane glider. "By running with the machine against the wind after the motor had been started, the aeroplane was made to skim along above the ground at heights of from 3 to 16 feet for a distance, without the operator touching, of about 350 yards. It was possible to have traveled a much longer distance, without the operator touching terra firma, but for the operator's desire not to get too far above it. Although the motor was not developing its full power, owing to the speed not exceeding 1,000 R.P.M., it developed sufficient to move the machine against the wind."The engine shown in the September 1903 article was the engine exhibited by Whitehead at the Second Annual Exhibit of the Aero Club of America in December 1906 that was shown in the photo between the Curtiss and Wright engines.

Aerial machines

Wing

A wing is an appendage with a surface that produces lift for flight or propulsion through the atmosphere, or through another gaseous or liquid fluid...

s were ribbed with bamboo, supported by steel

Steel

Steel is an alloy that consists mostly of iron and has a carbon content between 0.2% and 2.1% by weight, depending on the grade. Carbon is the most common alloying material for iron, but various other alloying elements are used, such as manganese, chromium, vanadium, and tungsten...

wires and were very similar to the shape of the Lilienthal glider's wings. The arrangement for folding the wings also closely followed the Lilienthal design. The craft was powered by two engines: a ground engine of 10 hp (7.5 kW), intended to propel the front wheels to reach takeoff

Takeoff

Takeoff is the phase of flight in which an aerospace vehicle goes from the ground to flying in the air.For horizontal takeoff aircraft this usually involves starting with a transition from moving along the ground on a runway. For balloons, helicopters and some specialized fixed-wing aircraft , no...

speed, and a 20 hp (15 kW) acetylene engine powering two propellers, which were designed to counter-rotate

Counter-rotating propellers

Counter-rotating propellers, found on twin- and multi-engine propeller-driven aircraft, spin in directions opposite one another.The propellers on both engines of most conventional twin-engined aircraft spin clockwise . Counter-rotating propellers generally spin clockwise on the left engine and...

for stability.

Whitehead owned and read a copy of Octave Chanute

Octave Chanute

Octave Chanute was a French-born American railway engineer and aviation pioneer. He provided the Wright brothers with help and advice, and helped to publicize their flying experiments. At his death he was hailed as the father of aviation and the heavier-than-air flying machine...

's famed 1894 "Progress in Flying Machines." Chanute detailed Count D'Esterno's design, along with a top view drawing of the machine, which was not built. The design of Whitehead's No. 21 1899–1901 monoplane shared many important features with the design of D'Esterno's 1864 monoplane glider and Penaud and Gauchot's 1876 monoplane.

Whitehead described his No. 22 aircraft and compared some of its features to the No. 21 in a letter he wrote to the editor of American Inventor magazine, published 1 April 1902. He said the No. 22 had a five-cylinder 40 hp kerosene

Kerosene

Kerosene, sometimes spelled kerosine in scientific and industrial usage, also known as paraffin or paraffin oil in the United Kingdom, Hong Kong, Ireland and South Africa, is a combustible hydrocarbon liquid. The name is derived from Greek keros...

motor of his own design, weighing 120 lbs. He said ignition was "accomplished by its own heat and compression." He described the aircraft as 16 feet (4.9 m) long, made mostly of steel and aluminum with wing ribs made of steel tubing, rather than bamboo, which was used in the Number 21 aircraft. He explained that the two front wheels were connected to the kerosene motor, and the rear wheels were used for steering while on the ground. He said the wing area was 450 square feet (41.8 m²), and the covering was "the best silk obtainable." The propellers were "6 feet in diameter...made of wood...covered with very thin aluminum sheeting." He said the tail and wings could all be "folded up...and laid against the sides of the body."

Whitehead also built gliders until about 1906 and was photographed flying them.

Later career

In addition to his work on flying machines, Whitehead built engines. Air EnthusiastAir Enthusiast

Air Enthusiast was a British, bi-monthly, aviation magazine, published by the Key Publishing group. Initially begun in 1974 as Air Enthusiast Quarterly, the magazine was conceived as a historical adjunct to Air International magazine...

wrote: "In fact, Weisskopf's ability and mechanical skill could have made him a wealthy man at a time when there was an ever-increasing demand for lightweight engines, but he was far more interested in flying." Instead, Whitehead only accepted enough engine orders to sustain aviation experiments.

Whitehead's business practices were unsophisticated and he was sued by a customer, resulting in a threat that his tools and equipment would be seized. He hid his engines and most of his tools in a neighbor's cellar and continued his aviation work. One of his engines was installed by aviation pioneer Charles Wittemann

Wittemann brothers

Adolph Wittemann and Charles Rudolph Wittemann were early aviation pioneers.-Biography:They were the children of Emily Wittemann of Missouri. Their father, who died prior to 1910, was from Germany. Charles and Adolph had a company: C. & A. Wittemann of Staten Island, New York. At Teterboro they...

in a helicopter built by Lee Burridge of the Aero Club of America, but the craft failed to fly.

Whitehead's own 1911 studies of the vertical flight problem resulted in a 60-bladed helicopter, which, unmanned, lifted itself off the ground.

He lost an eye in a factory accident and also suffered a severe blow to the chest from a piece of factory equipment, an injury that may have led to increasing attacks of angina. Despite these setbacks he exhibited an aircraft at Hempstead, New York, as late as 1915. He continued to work and invent. He designed a braking safety device, hoping to win a prize offered by a railroad. He demonstrated it as a scale model but won nothing. He constructed an "automatic" concrete-laying machine, which he used to help build a road north of Bridgeport. These inventions, however, brought him no more profit than did his airplanes and engines. Around 1915 Whitehead worked in a factory as laborer and repaired motors to support his family.

With World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

came prejudice against Germans. Whitehead never lost his German accent and never acquired American citizenship

United States nationality law

Article I, section 8, clause 4 of the United States Constitution expressly gives the United States Congress the power to establish a uniform rule of naturalization. The Immigration and Naturalization Act sets forth the legal requirements for the acquisition of, and divestiture from, citizenship of...

.

He died of a massive heart attack

Myocardial infarction

Myocardial infarction or acute myocardial infarction , commonly known as a heart attack, results from the interruption of blood supply to a part of the heart, causing heart cells to die...

, on 10 October 1927, after attempting to lift an engine out of an automobile he was repairing. He stumbled onto his front porch and into his home, then collapsed dead in the house.

Rediscovery

Whitehead's work remained almost completely unknown to the public and aeronautical community until a 1935 article in Popular Aviation magazine co-authored by Stella Randolph, an aspiring writer, and aviation historyAviation history

The history of aviation has extended over more than two thousand years from the earliest attempts in kites and gliders to powered heavier-than-air, supersonic and hypersonic flight.The first form of man-made flying objects were kites...

buff Harvey Phillips. Randolph expanded the article into a book, "Lost Flights of Gustave Whitehead," published in 1937. Randolph sought out people who had known Whitehead and had seen his flying machines and engines. She obtained 16 affidavits from 14 people and included the text of their statements in the book. Four people said they did not see flights, while the others said they saw flights of various types, ranging from a few dozen to hundreds of feet to more than a mile.

Harvard University

Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League university located in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States, established in 1636 by the Massachusetts legislature. Harvard is the oldest institution of higher learning in the United States and the first corporation chartered in the country...

economics professor John B. Crane wrote an article published in National Aeronautic Magazine in December 1936, disputing claims and reports that Whitehead flew. The following year, after further research, Crane adopted a different tone. He told reporters, "There are several people still living in Bridgeport who testified to me under oath they had seen Whitehead make flights along the streets of Bridgeport in the early 1900s." Crane repeated Harworth's claim of having witnessed a one-and-a-half mile airplane flight made by Whitehead on 14 August 1901. He suggested a Congressional investigation to consider the claims.

In 1949 Crane published a new article in Air Affairs magazine that supported claims that Whitehead flew.

In 1963 William O'Dwyer, a reserve U.S. Air Force major, accidentally discovered photographs of a 1910 Whitehead "Large Albatross"-type biplane aircraft shown at rest on the ground, the collection found in the attic of a Connecticut house. He then devoted himself to researching Whitehead and became convinced he had made powered flights before the Wright brothers. O'Dwyer contributed to a second book by Stella Randolph, The Story of Gustave Whitehead, Before the Wrights Flew, published in 1966. They co-authored another book, History by Contract

History by Contract

History by Contract, published in 1978, is a book written by Major William J. O'Dwyer, U.S. Air Force Reserve , of Fairfield, Conn. about the aviation pioneer Gustave Whitehead....

, published in 1978, which criticized the Smithsonian Institution

Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution is an educational and research institute and associated museum complex, administered and funded by the government of the United States and by funds from its endowment, contributions, and profits from its retail operations, concessions, licensing activities, and magazines...

for inadequately investigating claims that Whitehead flew.

In 1968, Connecticut officially recognized Whitehead as "Father of Connecticut Aviation". Seventeen years later, the North Carolina General Assembly

North Carolina General Assembly

The North Carolina General Assembly is the state legislature of the U.S. state of North Carolina. The General Assembly drafts and legislates the state laws of North Carolina, also known as the General Statutes...

passed a resolution which repudiated the Connecticut statement and gave "no credence" to the assertion that Whitehead was first to fly, citing "leading aviation historians and the world's largest aviation museum" who determined there was "no historic fact, documentation, record or research to support the claim".

Witnesses

The article in the Bridgeport Sunday Herald of 18 August 1901 explicitly named two witnesses to Whitehead's reported early morning flight of August 14, 1901: Andrew Cellie and James Dickie.Decades later, Dickie denied seeing a flight. He said in a 1937 affidavit taken during Stella Randolph's research that he was not present at the reported flight on 14 August 1901, that he did not know Andrew Cellie, the other associate of Whitehead who was supposed to be there, and that none of Whitehead's aircraft ever flew, to the best of his knowledge.

Dickie said he did not believe that an airplane in photographs that were shown to him ever flew. An article in Air Enthusiast countered by saying that the description Dickie gave of the airplane did not match Whitehead's Number 21.

O'Dwyer had known the older Dickie since childhood. Early in his research, O'Dwyer spoke by telephone to Dickie. O'Dwyer learned that Dickie had a grudge against Whitehead. O'Dwyer described the conversation:

...his mood changed to anger when I asked him about Gustave Whitehead.

He flatly refused to talk about Whitehead, and when I asked him why, he said: "That SOB never paid me what he owed me. My father had a hauling business and I often hitched up the horses and helped Whitehead take his airplane to where he wanted to go. I will never give Whitehead credit for anything. I did a lot of work for him and he never paid me a dime."

O'Dwyer said he thought Dickie's 1937 affidavit had "little value." He said there were inconsistencies between the affidavit and his interview with Dickie.

The other man who the Sunday Herald said was an eyewitness to the reported flight on 14 August 1901 was believed to be Andrew Cellie, but he could not be found in the 1930s when Randolph investigated. O'Dwyer said that in the 1970s he searched through old Bridgeport city directories and concluded that the newspaper misspelled the man's name, which was actually Andrew Suelli, who was a Swiss or German immigrant also known as Zulli, and was Whitehead's next door neighbor before moving to the Pittsburgh area in 1902. Cellie's former neighbors in Fairfield told O'Dwyer that Cellie, who died before O'Dwyer investigated, had "always claimed he was present when Whitehead flew in 1901."

Junius Harworth and Anton Pruckner, who sometimes helped or worked for Whitehead, gave statements decades later as part of Stella Randolph's research, claiming they saw Whitehead fly on 14 August 1901.

Anton Pruckner, a tool maker who worked a few years with Whitehead, attested in 1934 to the flight. He also attested to a January 1902 flight by Whitehead over Long Island Sound, but the 1988 Air Enthusiast article said "Pruckner was not present on the occasion, though he was told of the events by Weisskopf himself."

In his first letter to American Inventor, Whitehead claimed he made four "trips" in the airplane on 14 August 1901; and that the longest was one and a half miles.

Discrepancies in statements by witnesses about different flights they said they saw on 14 August 1901, raised questions whether any flight was made. The Bridgeport Sunday Herald reported a half mile flight occurred early in the morning on 14 August. Whitehead and Harworth later claimed that a flight one and a half miles long was made that day.

Among the affidavits collected by Stella Randolph are these, quoted in part:

- Affidavit: Joe Ratzenberger – 28 January 1936:

- "I recall a time, which I think was probably July or August of 1901 or 1902, when this plane was started in flight on the lot between Pine and Cherry Streets. The plane flew at a height of about twelve feet from the ground, I should judge, and traveled the distance to Bostwick Avenue before it came to the ground."

- Affidavit: Thomas Schweibert – 15 June 1936:

- "I... recall seeing an airplane flight made by the late Gustave Whitehead approximately thirty-five years ago. I was a boy at the time, playing on a lot near the Whitehead shop on Cherry Street, and recall the incident well as we were surprised to see the plane leave the ground. It traveled a distance of approximately three hundred feet, and at a height of approximately fifteen feet in the air, to the best of my recollection."

- Affidavit by Junius Harworth – 21 August 1934:

- "On August, fourteenth, Nineteen Hundred and One I was present and assisted on the occasion when Mr. Whitehead succeeded in flying his machine, propelled by a motor, to a height of two hundred feet off the ground or sea beach at Lordship Manor, Connecticut. The distance flown was approximately one mile and a half".

O'Dwyer organized a survey of surviving witnesses to the reported Whitehead flights. Members of the Connecticut Aeronautical Historical Association (CAHA) and the 9315th Squadron (O'Dwyer's U.S. Air Force Reserve unit) went door-to-door in Bridgeport, Fairfield, Stratford, and Milford, Connecticut to track down Whitehead's long-ago neighbors and helpers. They also traced some who had moved to other parts of the state and the U.S. Of an estimated 30 persons interviewed for affidavits or on tape, 20 said they had seen flights, eight indicated they had heard of the flights, and two said that Whitehead did not fly.

Photos

Another missing photo that purportedly showed a Whitehead aircraft in flight was displayed in the 1906 First Annual Exhibit of the Aero Club of America at the 69th Regiment Armory

69th Regiment Armory

The 69th Regiment Armory located at 68 Lexington Avenue between East 25th and 26th Streets in Manhattan, New York City is a historical building which began construction in 1904 and was completed in 1906. The building is still used to house the U.S. 69th Infantry Regiment, as well as for the...

in New York City. The photo was mentioned in a 27 January 1906 Scientific American

Scientific American

Scientific American is a popular science magazine. It is notable for its long history of presenting science monthly to an educated but not necessarily scientific public, through its careful attention to the clarity of its text as well as the quality of its specially commissioned color graphics...

magazine article. The article said the walls of the exhibit room were covered with a large collection of photographs showing the machines of inventors such as Whitehead, Henry Berliner

Henry Berliner

Henry Adler Berliner was a United States aircraft and helicopter pioneer. Sixth son of inventor Emile Berliner, he was born in Washington, D.C....

and Alberto Santos-Dumont

Alberto Santos-Dumont

Alberto Santos-Dumont , was a Brazilian early pioneer of aviation. The heir of a wealthy family of coffee producers, Santos Dumont dedicated himself to science studies in Paris, France, where he spent most of his adult life....

. Other photographs showed airships and balloons in flight. The report said a single blurred photograph of a large birdlike machine propelled by compressed air constructed by Whitehead in 1901 was the only other photograph besides that of Samuel Pierpont Langley

Samuel Pierpont Langley

Samuel Pierpont Langley was an American astronomer, physicist, inventor of the bolometer and pioneer of aviation...

's scale model

Scale model

A scale model is a physical model, a representation or copy of an object that is larger or smaller than the actual size of the object, which seeks to maintain the relative proportions of the physical size of the original object. Very often the scale model is used as a guide to making the object in...

machines of a motor-driven aeroplane in successful flight. In 1986, Peter L. Jakab, National Air and Space Museum

National Air and Space Museum

The National Air and Space Museum of the Smithsonian Institution holds the largest collection of historic aircraft and spacecraft in the world. It was established in 1976. Located in Washington, D.C., United States, it is a center for research into the history and science of aviation and...

(NASM) Associate Director and Curator of Early Flight, wrote that the image "may very well have been an in-flight photograph" of one of Whitehead's gliders.

Two Connecticut Whitehead fans said they heard about yet another photograph: high school science teacher and pilot Andy Kosch, and Connecticut State Senator George Gunther

George Gunther

George "Doc" Gunther is the longest-serving state legislator in Connecticut history. Senator Gunther represented the 21st Connecticut Senate District, comprising all of Shelton, most of Stratford, and parts of Monroe and Seymour, Connecticut, from 1966 to 2006...

. They were told that a sea captain named Brown made a logbook entry about Whitehead flying over Long Island Sound and even photographed the airplane in flight. A friend told Kosch he found the captain's leather-bound journal containing a photo of Whitehead in flight and a description of the event. After some difficulty, Kosch made contact with the owners of the journal, but they told him it was lost.

Replicas

To show that the No. 21 aircraft might have flown, Kosch formed the group "Hangar 21" and led construction of an American reproduction of the craft. On 29 December 1986 Kosch made 20 flights and reached a maximum distance of 100 m (328.1 ft). The reproduction, dubbed "21B," was also shown at the 1986 Experimental Aircraft Association Fly-In.In 1986, American actor and accomplished aviator Cliff Robertson

Cliff Robertson

Clifford Parker "Cliff" Robertson III was an American actor with a film and television career that spanned half of a century. Robertson portrayed a young John F. Kennedy in the 1963 film PT 109, and won the 1968 Academy Award for Best Actor for his role in the movie Charly...

, was contacted by the Hangar 21 group in Bridgeport and was asked to attempt to fly their reproduction No.21 while under tow behind a sports car, for the benefit of the press. Robertson said "We did a run and nothing happened. And we did a second run and nothing happened. Then the wind came up a little and we did another run and, sure enough, I got her up and flying. Then we went back and did a second one." Robertson commented, "We will never take away the rightful role of the Wright Brothers, but if this poor little German immigrant did indeed get an airplane to go up and fly one day, then let's give him the recognition he deserves."

On 18 February 1998 another reproduction of No. 21 was flown 500 m (1,640.4 ft) in Germany.

The Herald article and drawing

The writer of the Whitehead article in the Bridgeport Sunday Herald of 18 August 1901 is widely believed to have been sports editor Richard Howell, but no byline appeared on the article, and the drawing of the aircraft flying was not signed. In 1937 Stella Randolph stated in her first book that the author of the article was Richard Howell.O'Dwyer believed that Howell made the drawing of the No. 21 in flight, saying that Howell was "an artist before he became a reporter."

O'Dwyer spent hours in the Bridgeport Library studying virtually everything Howell wrote. O'Dwyer said: "Howell was always a very serious writer. He always used sketches rather than photographs with his features on inventions. He was highly regarded by his peers on other local newspapers. He used the florid style of the day, but was not one to exaggerate. Howell later became the Herald

Kosch said, "If you look at the reputation of the editor of the Bridgeport Herald in those days, you find that he was a reputable man. He wouldn't make this stuff up." Howell died before the controversy about Whitehead began.

The Sunday Herald article was published 18 August 1901, four days after the event it described. According to Aviation History, Whitehead detractors, including Orville Wright, used the delay in publication to cast doubt on the story, questioning why the newspaper would wait four days before reporting such important news. Orville Wright's critical comments were later quoted by the both the Smithsonian Institution and by British aviation historian Charles Harvard Gibbs-Smith

Charles Harvard Gibbs-Smith

Charles Harvard Gibbs-Smith was a British polymath historian of aeronautics and aviation. His obituary in the Times described him as "the recognised authority on the early development of flying in Europe and America" Richard P...

. Aviation History explained that the Bridgeport Sunday Herald was a weekly newspaper published only on Sundays.

Mrs. Whitehead and skeptics

An early source of ammunition for both sides of the debate was a 1940 interview of Whitehead's wife Louise. The Bridgeport Sunday Post reported that Mrs. Whitehead said her husband's first words upon returning home from Fairfield on 14 August 1901, were an excited, "Mama, we went up!" Mrs. Whitehead said her husband was always busy with motors and flying machines when he was not working in coal yards or factories. The interview quoted her as saying, "I hated to see him put so much time and money into that work." Mrs. Whitehead said her husband's aviation efforts took their toll on the family budget and she had to work to help meet expenses. She said she never saw any of her husband's reported flights.As to whether Whitehead's wife resented matters, Stella Randolph wrote "Mrs. Whitehead talked very freely and frankly with the writer, who made several visits to her home, in the 1930s, and there was never any intimation that she harbored any resentment about the past."

Smithsonian Institution Curator of Aeronautics Peter L. Jakab said that Whitehead's wife and family did not know about his August 1901 flights.

Stanley Beach

Stanley Yale Beach was the son of the editor of Scientific American magazine and later became editor himself. He had a long personal association with Whitehead. His father, Frederick C. Beach, contributed thousands of dollars to support Whitehead's aeronautical work. Whitehead built an under-powered over-weight biplane that Stanley Beach designed, which never flew.Beach claimed authorship of only one Scientific American article about Whitehead, that of 8 June 1901, a few weeks before the report in the Bridgeport Sunday Herald. The Scientific American article by Beech described Whitehead's machine as a "novel flying machine." Two photographs were included of a "batlike" craft.". The article did not state Whitehead had flown and was published before Whitehead's reported flight of 14 August 1901. Unsigned articles in Scientific American in 1906 and 1908 did state that Whitehead had flown in 1901, but gave no details.