.gif)

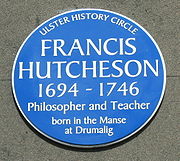

Francis Hutcheson (philosopher)

Encyclopedia

Kingdom of Ireland

The Kingdom of Ireland refers to the country of Ireland in the period between the proclamation of Henry VIII as King of Ireland by the Crown of Ireland Act 1542 and the Act of Union in 1800. It replaced the Lordship of Ireland, which had been created in 1171...

to a family of Scottish

Scotland

Scotland is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Occupying the northern third of the island of Great Britain, it shares a border with England to the south and is bounded by the North Sea to the east, the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, and the North Channel and Irish Sea to the...

Presbyterians who became one of the founding fathers of the Scottish Enlightenment

Scottish Enlightenment

The Scottish Enlightenment was the period in 18th century Scotland characterised by an outpouring of intellectual and scientific accomplishments. By 1750, Scots were among the most literate citizens of Europe, with an estimated 75% level of literacy...

.

Hutcheson was an important influence on the works of several significant Enlightenment thinkers, including David Hume

David Hume

David Hume was a Scottish philosopher, historian, economist, and essayist, known especially for his philosophical empiricism and skepticism. He was one of the most important figures in the history of Western philosophy and the Scottish Enlightenment...

and Adam Smith

Adam Smith

Adam Smith was a Scottish social philosopher and a pioneer of political economy. One of the key figures of the Scottish Enlightenment, Smith is the author of The Theory of Moral Sentiments and An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations...

.

Early life

He is thought to have been born at Drumalig, in the parish of SaintfieldSaintfield

Saintfield is a village in County Down, Northern Ireland, situated roughly halfway between Belfast and Downpatrick on the A7 road. It had a population of 2,959 people in the 2001 Census. The village proper is considered predominantly a middle or upper-middle class town and of both Catholic and...

, County Down

County Down

-Cities:*Belfast *Newry -Large towns:*Dundonald*Newtownards*Bangor-Medium towns:...

, Ireland

Ireland

Ireland is an island to the northwest of continental Europe. It is the third-largest island in Europe and the twentieth-largest island on Earth...

. He was the "son of a Presbyterian minister of Ulster Scottish (or 'Scots–Irish') stock, who was born in Ireland." Hutcheson was educated at Killyleagh

Killyleagh

Killyleagh is a village in County Down, Northern Ireland. It is on the A22 road from Downpatrick, on the western side of Strangford Lough. It had a population of 2,483 people in the 2001 Census. It is best known for its 12th century Killyleagh Castle...

, and went on to Scotland to study at the University of Glasgow

University of Glasgow

The University of Glasgow is the fourth-oldest university in the English-speaking world and one of Scotland's four ancient universities. Located in Glasgow, the university was founded in 1451 and is presently one of seventeen British higher education institutions ranked amongst the top 100 of the...

, where he spent six years at first in the study of philosophy, classics and general literature, and afterwards in the study of theology

Theology

Theology is the systematic and rational study of religion and its influences and of the nature of religious truths, or the learned profession acquired by completing specialized training in religious studies, usually at a university or school of divinity or seminary.-Definition:Augustine of Hippo...

, receiving his degree in 1712. While a student, he worked as tutor to the Earl of Kilmarnock

William Boyd, 3rd Earl of Kilmarnock

William Boyd, 3rd Earl of Kilmarnock was a Scottish nobleman.He fought for the British Government during the Jacobite rising of 1715....

. He was licensed as a minister of the Church of Scotland in 1716.

Return to Ireland

Facing suspicions about his "Irish" roots and his association with New Licht theologian John SimsonJohn Simson

John Simson was a Scottish New Licht theologian, involved in a long investigation of alleged heresy. He was suspended from teaching as Professor of Divinity, Glasgow, for the rest of his life.-Life:...

(then under investigation by Scottish ecclesiastical courts), a ministry in Scotland was unlikely to be a success, so he left the church returning to Ireland to pursue a career in academia. He was induced to start a private academy in Dublin, where he taught for 10 years, studying philosophy on the side and producing his famous Inquiry (1725). In Dublin his literary attainments gained him the friendship of many prominent inhabitants. Among these was Archbishop of Dublin, William King

William King (archbishop)

William King, D.D. was an Anglican divine in the Church of Ireland, who was Archbishop of Dublin from 1703 to 1729. He was an author and supported the Glorious Revolution.-Early life:...

, who refused to prosecute Hutcheson in the archbishop's court for keeping a school without the episcopal licence. Hutcheson's relations with the clergy of the Established Church, especially with King and with Hugh Boulter

Hugh Boulter

Hugh Boulter was the Church of Ireland Archbishop of Armagh, the Primate of All Ireland, from 1724 until his death. He also served as the chaplain to George I from 1719.-Background and education:...

(the archbishop of Armagh) seem to have been cordial, and his biographer, speaking of "the inclination of his friends to serve him, the schemes proposed to him for obtaining promotion," etc., probably refers to some offers of preferment, on condition of his accepting episcopal ordination.

While residing in Dublin, Hutcheson published anonymously the four essays he is best known by: the Inquiry concerning Beauty, Order, Harmony and Design, the Inquiry concerning Moral Good and Evil, in 1725, the Essay on the Nature and Conduct of the Passions and Affections and Illustrations upon the Moral Sense, in 1728. The alterations and additions made in the second edition of these Essays were published in a separate form in 1726. To the period of his Dublin residence are also to be referred the Thoughts on Laughter (1725) (a criticism of Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes of Malmesbury , in some older texts Thomas Hobbs of Malmsbury, was an English philosopher, best known today for his work on political philosophy...

) and the Observations on the Fable of the Bees, being in all six letters contributed to Hibernicus' Letters, a periodical that appeared in Dublin (1725–1727, 2nd ed. 1734). At the end of the same period occurred the controversy in the London Journal with Gilbert Burnet (probably the second son of Dr Gilbert Burnet

Gilbert Burnet

Gilbert Burnet was a Scottish theologian and historian, and Bishop of Salisbury. He was fluent in Dutch, French, Latin, Greek, and Hebrew. Burnet was respected as a cleric, a preacher, and an academic, as well as a writer and historian...

, bishop of Salisbury

Bishop of Salisbury

The Bishop of Salisbury is the ordinary of the Church of England's Diocese of Salisbury in the Province of Canterbury.The diocese covers much of the counties of Wiltshire and Dorset...

) on the "True Foundation of Virtue or Moral Goodness." All these letters were collected in one volume (Glasgow, 1772).

Chair of Moral Philosophy at Glasgow

In 1729, Hutcheson succeeded his old master, Gershom CarmichaelGershom Carmichael

Gershom Carmichael was a Scottish philosopher.Gershom Carmichael was a Scottish subject born in London, the son of Alexander Charmichael, a Church of Scotland minister who had been banished by the Scottish privy council for his religious opinions...

, in the Chair of Moral Philosophy

Professor of Moral Philosophy, Glasgow

The Chair of Moral Philosophy is a professorship at the University of Glasgow, Scotland, which was established in 1727.The Nova Erectio of King James VI of Scotland shared the teaching of Moral Philosophy, Logic and Natural Philosophy among the Regents...

at the University of Glasgow

University of Glasgow

The University of Glasgow is the fourth-oldest university in the English-speaking world and one of Scotland's four ancient universities. Located in Glasgow, the university was founded in 1451 and is presently one of seventeen British higher education institutions ranked amongst the top 100 of the...

, being the first professor there to lecture in English instead of Latin. It is curious that up to this time all his essays and letters had been published anonymously, though their authorship appears to have been well known. In 1730 he entered on the duties of his office, delivering an inaugural lecture (afterwards published), De naturali hominum socialitate (About the natural fellowship of mankind). He appreciated having leisure for his favourite studies; "non levi igitur laetitia commovebar cum almam matrem Academiam me, suum olim alumnum, in libertatem asseruisse audiveram." (I was, therefore, moved by no mean frivolous pleasure when I had heard that my alma mater

Alma mater

Alma mater , pronounced ), was used in ancient Rome as a title for various mother goddesses, especially Ceres or Cybele, and in Christianity for the Virgin Mary.-General term:...

had delivered me, its one time alumnus

Alumnus

An alumnus , according to the American Heritage Dictionary, is "a graduate of a school, college, or university." An alumnus can also be a former member, employee, contributor or inmate as well as a former student. In addition, an alumna is "a female graduate or former student of a school, college,...

, into freedom.) Yet the works on which Hutcheson's reputation rests had already been published. During his time as a lecturer in Glasgow College he taught Adam Smith

Adam Smith

Adam Smith was a Scottish social philosopher and a pioneer of political economy. One of the key figures of the Scottish Enlightenment, Smith is the author of The Theory of Moral Sentiments and An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations...

, the economist and philosopher. Not only did his ideas have great influence on Smith's later work The Theory of Moral Sentiments

The Theory of Moral Sentiments

The Theory of Moral Sentiments was written by Adam Smith in 1759. It provided the ethical, philosophical, psychological, and methodological underpinnings to Smith's later works, including The Wealth of Nations , A Treatise on Public Opulence , Essays on Philosophical Subjects , and Lectures on...

, "the order of topics of Hutcheson's lectures, as published in the System and as heard by young Smith at the University of Glasgow, is almost the same as the order of chapters in the Wealth of Nations."

However, it was likely not Hutcheson's written work that had such a great influence on Smith. Hutcheson was well regarded as one of the most prominent lecturers at the University of Glasgow in his day and earned the approbation of students, colleagues, and even ordinary residents of Glasgow with the fervor and earnestness of his orations. His roots as a minister indeed shone through in his lectures, which endeavored not merely to teach philosophy but to make his students embody that philosophy in their lives (appropriately acquiring the epithet, preacher of philosophy). Unlike Smith, Hutcheson was not a system builder; rather it was his magnetic personality and method of lecturing that so influenced his students and caused the greatest of those to reverentially refer to him as "the never to be forgotten Hutcheson"––a title that Smith in all his correspondence used to describe only two people, his good friend David Hume

David Hume

David Hume was a Scottish philosopher, historian, economist, and essayist, known especially for his philosophical empiricism and skepticism. He was one of the most important figures in the history of Western philosophy and the Scottish Enlightenment...

and influential mentor Francis Hutcheson.

Other works

In addition to the works named, the following were published during Hutcheson's lifetime: a pamphlet entitled Considerations on Patronage (1735); Philosophiae moralis institutio compendiaria, ethices et jurisprudentiae naturalis elementa continens, lib. iii. (Glasgow, 1742); Metaphysicae synopsis ontologiam et pneumatologiam campleciens (Glasgow, 1742). The last work was published anonymously. After his death, his son, Francis HutchesonFrancis Hutcheson (songwriter)

Francis Hutcheson was a Scottish songwriter.He was the author of a number of popular songs, including "As Cohn one evening", "Jolly Bacchus" and "Where Weeping Yews". The son of philosopher Francis Hutcheson, he published some of his father's work after the latter's death.-References:*Dictionary...

published much the longest, though by no means the most interesting, of his works, A System of Moral Philosophy, in Three Books (2 vols.. London, 1755). To this is prefixed a life of the author, by Dr William Leechman

William Leechman

-Life:The son of William Leechman, a farmer of Dolphinton, Lanarkshire, he was educated at the parish school; theT father had taken down the quarters of Robert Baillie of Jerviswood, which had been exposed after his execution on the tolbooth of Lanark...

, professor of divinity in the University of Glasgow. The only remaining work assigned to Hutcheson is a small treatise on Logic (Glasgow, 1764). This compendium, together with the Compendium of Metaphysics, was republished at Strassburg in 1722.

Thus Hutcheson dealt with metaphysics

Metaphysics

Metaphysics is a branch of philosophy concerned with explaining the fundamental nature of being and the world, although the term is not easily defined. Traditionally, metaphysics attempts to answer two basic questions in the broadest possible terms:...

, logic

Logic

In philosophy, Logic is the formal systematic study of the principles of valid inference and correct reasoning. Logic is used in most intellectual activities, but is studied primarily in the disciplines of philosophy, mathematics, semantics, and computer science...

and ethics

Ethics

Ethics, also known as moral philosophy, is a branch of philosophy that addresses questions about morality—that is, concepts such as good and evil, right and wrong, virtue and vice, justice and crime, etc.Major branches of ethics include:...

. His importance is, however, due almost entirely to his ethical writings, and among these primarily to the four essays and the letters published during his time in Dublin. His standpoint has a negative and a positive aspect; he is in strong opposition to Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes of Malmesbury , in some older texts Thomas Hobbs of Malmsbury, was an English philosopher, best known today for his work on political philosophy...

and Mandeville

Bernard de Mandeville

Bernard Mandeville, or Bernard de Mandeville , was a philosopher, political economist and satirist. Born in the Netherlands, he lived most of his life in England and used English for most of his published works...

, and in fundamental agreement with Shaftesbury, whose name he very properly coupled with his own on the title page of the first two essays. Obvious and fundamental points of agreement between the two authors include the analogy drawn between beauty and virtue, the functions assigned to the moral sense, the position that the benevolent feelings form an original and irreducible part of our nature, and the unhesitating adoption of the principle that the test of virtuous action is its tendency to promote the general welfare.

Ethics

According to Hutcheson, man has a variety of senses, internal as well as external, reflex as well as direct, the general definition of a sense being "any determination of our minds to receive ideas independently on our will, and to have perceptions of pleasure and pain" (Essay on the Nature and Conduct of the Passions, sect. 1). He does not attempt to give an exhaustive enumeration of these "senses," but, in various parts of his works, he specifies, besides the five external senses commonly recognized (which he hints might be added to):- consciousness, by which each man has a perception of himself and of all that is going on in his own mind (Metaph. Syn. pars i. cap. 2)

- the sense of beauty (sometimes called specifically "an internal sense")

- a public sense, or sensus communis, "a determination to be pleased with the happiness of others and to be uneasy at their misery"

- the moral sense, or "moral sense of beauty in actions and affections, by which we perceive virtue or vice, in ourselves or others"

- a sense of honour, or praise and blame, "which makes the approbation or gratitude of others the necessary occasion of pleasure, and their dislike, condemnation or resentment of injuries done by us the occasion of that uneasy sensation called shame"

- a sense of the ridiculous. It is plain, as the author confesses, that there may be "other perceptions, distinct from all these classes," and, in fact, there seems to be no limit to the number of "senses" in which a psychological division of this kind might result.

Of these "senses," the "moral sense" plays the most important part in Hutcheson's ethical system. It pronounces immediately on the character of actions and affections, approving those that are virtuous, and disapproving those that are vicious. "His principal design," he says in the preface to the two first treatises, "is to show that human nature was not left quite indifferent in the affair of virtue, to form to itself observations concerning the advantage or disadvantage of actions, and accordingly to regulate its conduct. The weakness of our reason, and the avocations arising from the infirmity and necessities of our nature, are so great that very few men could ever have formed those long deductions of reasons that show some actions to be in the whole advantageous to the agent, and their contraries pernicious. The Author of nature has much better furnished us for a virtuous conduct than our moralists seem to imagine, by almost as quick and powerful instructions as we have for the preservation of our bodies. He has made virtue a lovely form, to excite our pursuit of it, and has given us strong affections to be the springs of each virtuous action."

Passing over the appeal to final causes involved in this passage, as well as the assumption that the "moral sense" has had no growth or history, but was "implanted" in man exactly as found among the more civilized races—an assumption common to both Hutcheson and Butler

Joseph Butler

Joseph Butler was an English bishop, theologian, apologist, and philosopher. He was born in Wantage in the English county of Berkshire . He is known, among other things, for his critique of Thomas Hobbes's egoism and John Locke's theory of personal identity...

—his use of the term "sense" tends to obscure the real nature of the process of moral judgment. For, as established by Hume

David Hume

David Hume was a Scottish philosopher, historian, economist, and essayist, known especially for his philosophical empiricism and skepticism. He was one of the most important figures in the history of Western philosophy and the Scottish Enlightenment...

, this act consists of two parts: an act of deliberation leading to an intellectual judgment; and a reflex feeling of satisfaction at actions we consider good, and of dissatisfaction at those we consider bad. By the intellectual part of this process, we refer the action or habit

Habit (psychology)

Habits are routines of behavior that are repeated regularly and tend to occur subconsciously. Habitual behavior often goes unnoticed in persons exhibiting it, because a person does not need to engage in self-analysis when undertaking routine tasks...

to a certain class; but no sooner is the intellectual process complete than there is excited in us a feeling similar to what myriads of actions and habits of (apparently) the same class excited in us on former occasions.

Even if the latter part of this process is instantaneous, uniform and exempt from error, the former is not. All mankind may approve of that which is virtuous or makes for the general good, but they entertain the most widely divergent opinions and frequently arrive at directly opposite conclusions as to particular actions and habits. Hutcheson recognizes this obvious distinction in his analysis of the mental process preceding moral action, and does not ignore it, even when writing on the moral approbation or disapprobation that follows action. Nonetheless, Hutcheson, both by his phraseology and the language he uses to describe the process of moral approbation, has done much to favour that loose, popular view of morality which, ignoring the necessity of deliberation and reflection, encourages hasty resolves and unpremeditated judgments.

The term "moral sense" (which, it may be noticed, had already been employed by Shaftesbury, not only, as William Whewell

William Whewell

William Whewell was an English polymath, scientist, Anglican priest, philosopher, theologian, and historian of science. He was Master of Trinity College, Cambridge.-Life and career:Whewell was born in Lancaster...

suggests, in the margin, but also in the text of his Inquiry), if invariably coupled with the term "moral judgment," would be open to little objection; but, taken alone, as designating the complex process of moral approbation, it is liable to lead not only to serious misapprehension but to grave practical errors. For, if each person's decisions are solely the result of an immediate intuition of the moral sense, why be at any pains to test, correct or review them? Or why educate a faculty whose decisions are infallible? And how do we account for differences in the moral decisions of different societies, and the observable changes in a person's own views? The expression has, in fact, the fault of most metaphorical terms: it leads to an exaggeration of the truth it is intended to suggest.

But though Hutcheson usually describes the moral faculty as acting instinctively and immediately, he does not, like Butler, confound the moral faculty with the moral standard. The test or criterion of right action is with Hutcheson, as with Shaftesbury, its tendency to promote the general welfare of mankind. He thus anticipates the utilitarianism of Bentham

Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham was an English jurist, philosopher, and legal and social reformer. He became a leading theorist in Anglo-American philosophy of law, and a political radical whose ideas influenced the development of welfarism...

--and not only in principle, but even in the use of the phrase "the greatest happiness for the greatest number" (Inquiry concerning Moral Good and Evil, sect. 3). Hutcheson does not seem to have seen an inconsistency between this external criterion with his fundamental ethical principle. Intuition has no possible connection with an empirical calculation of results, and Hutcheson in adopting such a criterion practically denies his fundamental assumption. Connected with Hutcheson's virtual adoption of the utilitarian standard is a kind of moral algebra, proposed for the purpose of "computing the morality of actions." This calculus occurs in the Inquiry concerning Moral Good and Evil, sect. 3.

Hutcheson's other distinctive ethical doctrine is what has been called the "benevolent theory" of morals. Hobbes had maintained that all other actions, however disguised under apparent sympathy, have their roots in self-love

Self-love

Self-love is the strong sense of respect for and confidence in oneself. It is different from narcissism in that as one practices acceptance and detachment, the awareness of the individual shifts and the individual starts to see him or herself as an extension of all there is...

. Hutcheson not only maintains that benevolence is the sole and direct source of many of our actions, but, by a not unnatural recoil, that it is the only source of those actions of which, on reflection, we approve. Consistently with this position, actions that flow from self-love only are morally indifferent. But surely, by the common consent of civilized men, prudence, temperance, cleanliness, industry, self-respect and, in general, the personal virtues," are regarded, and rightly regarded, as fitting objects of moral approbation.

This consideration could hardly escape any author, however wedded to his own system, and Hutcheson attempts to extricate himself from the difficulty by laying down the position that a man may justly regard himself as a part of the rational system, and may thus be, in part, an object of his own benevolence (Ibid),--a curious abuse of terms, which really concedes the question at issue. Moreover, he acknowledges that, though self-love does not merit approbation, neither, except in its extreme forms, did it merit condemnation, indeed the satisfaction of the dictates of self love is one of the very conditions of the preservation of society. To press home the inconsistencies involved in these various statement would be a superfluous task.

The vexed question of liberty and necessity appears to be carefully avoided in Hutcheson's professedly ethical works. But, in the Synopsis metaphysicae, he touches on it in three places, briefly stating both sides of the question, but evidently inclining to what he designates as the opinion of the Stoics, in opposition to what he designates as the opinion of the Peripatetics. This is substantially the same as the doctrine propounded by Hobbes and Locke

John Locke

John Locke FRS , widely known as the Father of Liberalism, was an English philosopher and physician regarded as one of the most influential of Enlightenment thinkers. Considered one of the first of the British empiricists, following the tradition of Francis Bacon, he is equally important to social...

(to the latter of whom Hutcheson refers in a note), namely that our will is determined by motives in conjunction with our general character and habit of mind, and that the only true liberty is the liberty of acting as we will, not the liberty of willing as we will. Though, however, his leaning is clear, he carefully avoids dogmatising, and deprecates the angry controversies to which the speculation on this subject had given rise.

It is easy to trace the influence of Hutcheson's ethical theories on the systems of Hume and Adam Smith

Adam Smith

Adam Smith was a Scottish social philosopher and a pioneer of political economy. One of the key figures of the Scottish Enlightenment, Smith is the author of The Theory of Moral Sentiments and An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations...

. The prominence given by these writers to the analysis of moral action and moral approbation with the attempt to discriminate the respective provinces of the reason and the emotions in these processes, is undoubtedly due to the influence of Hutcheson. To a study of the writings of Shaftesbury and Hutcheson we might, probably, in large measure, attribute the unequivocal adoption of the utilitarian standard by Hume, and, if this be the case, the name of Hutcheson connects itself, through Hume, with the names of Priestley

Joseph Priestley

Joseph Priestley, FRS was an 18th-century English theologian, Dissenting clergyman, natural philosopher, chemist, educator, and political theorist who published over 150 works...

, Paley

William Paley

William Paley was a British Christian apologist, philosopher, and utilitarian. He is best known for his exposition of the teleological argument for the existence of God in his work Natural Theology, which made use of the watchmaker analogy .-Life:Paley was Born in Peterborough, England, and was...

and Bentham. Butler

Joseph Butler

Joseph Butler was an English bishop, theologian, apologist, and philosopher. He was born in Wantage in the English county of Berkshire . He is known, among other things, for his critique of Thomas Hobbes's egoism and John Locke's theory of personal identity...

's Sermons appeared in 1726, the year after the publication of Hutcheson's two first essays, and the parallelism between the "conscience" of the one writer and the "moral sense" of the other is, at least, worthy of remark.

Mental philosophy

In the sphere of mental philosophy and logic Hutcheson's contributions are by no means so important or original as in that of moral philosophy. They are interesting mainly as a link between Locke and the Scottish school. In the former subject the influence of Locke is apparent throughout. All the main outlines of Locke's philosophy seem, at first sight, to be accepted as a matter of course. Thus, in stating his theory of the moral sense, Hutcheson is peculiarly careful to repudiate the doctrine of innate ideas (see, for instance, Inquiry concerning Moral Good and Evil, sect. I ad fin., and sect. 4; and compare Synopsis Metaphysicae, pars i. cap. 2). At the same time he shows more discrimination than does Locke in distinguishing between the two uses of this expression, and between the legitimate and illegitimate form of the doctrine (Syn. Metaph. pars i. cap. 2).All our ideas are, as by Locke, referred to external or internal sense, or, in other words, to sensation and reflection. It is, however, a most important modification of Locke's doctrine, and connects Hutcheson's mental philosophy with that of Reid

Thomas Reid

The Reverend Thomas Reid FRSE , was a religiously trained Scottish philosopher, and a contemporary of David Hume, was the founder of the Scottish School of Common Sense, and played an integral role in the Scottish Enlightenment...

, when he states that the ideas of extension, figure, motion and rest "are more properly ideas accompanying the sensations of sight and touch than the sensations of either of these senses"; that the idea of self accompanies every thought, and that the ideas of number, duration and existence accompany every other idea whatsoever (see Essay on the Nature and Conduct of the Passions, sect. i. art. I; Syn. Metaph. pars i. cap. 1, pars ii. cap. I; Hamilton on Reid, p. 124, note). Other important points in which Hutcheson follows the lead of Locke are his depreciation of the importance of the so-called laws of thought, his distinction between the primary and secondary qualities of bodies, the position that we cannot know the inmost essences of things ("intimae rerum naturae sive essentiae"), though they excite various ideas in us, and the assumption that external things are known only through the medium of ideas (Syn. Metaph. pars i. cap. I), though, at the same time, we are assured of the existence of an external world corresponding to these ideas.

Hutcheson attempts to account for our assurance of the reality of an external world by referring it to a natural instinct (Syn. Metaph. pars i. cap. 1). Of the correspondence or similitude between our ideas of the primary qualities of things and the things themselves God alone can be assigned as the cause. This similitude has been effected by Him through a law of nature. "Haec prima qualitatum primariarum perceptio, sive mentis actio quaedam sive passio dicatur, non alia similitudinis aut convenientiae inter ejusmodi ideas et res ipsas causa assignari posse videtur, quam ipse Deus, qui certa naturae lege hoc efilcit, Ut notiones, quae rebus praesentibus excitantur, sint ipsis similes, aut saltem earum habitudines, si non veras quantitates, depingant" (pars ii. cap. I). Locke does speak of God "annexing" certain ideas to certain motions of bodies; but nowhere does he propound a theory so definite as that here propounded by Hutcheson, which reminds us at least as much of the speculations of Nicolas Malebranche

Nicolas Malebranche

Nicolas Malebranche ; was a French Oratorian and rationalist philosopher. In his works, he sought to synthesize the thought of St. Augustine and Descartes, in order to demonstrate the active role of God in every aspect of the world...

as of those of Locke.

Amongst the more important points in which Hutcheson diverges from Locke is his account of the idea of personal identity, which he appears to have regarded as made known to us directly by consciousness. The distinction between body and mind, corpus or materia and res cogitans, is more emphatically accentuated by Hutcheson than by Locke. Generally, he speaks as if we had a direct consciousness of mind as distinct from body, though, in the posthumous work on Moral Philosophy, he expressly states that we know mind as we know body" by qualities immediately perceived though the substance of both be unknown (bk. i. ch. 1). The distinction between perception proper and sensation proper, which occurs by implication though it is not explicitly worked out (see Hamilton's Lectures on Metaphysics, - Lect. 24).

Hamilton's edition of Dugald Stewart

Dugald Stewart

Dugald Stewart was a Scottish Enlightenment philosopher and mathematician. His father, Matthew Stewart , was professor of mathematics in the University of Edinburgh .-Life and works:...

's Works, v. 420),--the imperfection of the ordinary division of the external senses into two classes, the limitation of consciousness to a special mental facult) (severely criticized in Sir W Hamilton's Lectures on Metaphysics Lect. xii.) and the disposition to refer on disputed questions of philosophy not so much to formal arguments as to the testimony of consciousness and our natural instincts are also amongst the points in which Hutcheson supplemented or departed from the philosophy of Locke. The last point can hardly fail to suggest the "common-sense philosophy" of Reid.

Thus, in estimating Hutcheson's position, we find that in particular questions he stands nearer to Locke, but in the general spirit of his philosophy he seems to approach more closely to his Scottish successors.

The short Compendium of Logic, which is more original than such works usually are, is remarkable chiefly for the large proportion of psychological matter that it contains. In these parts of the book Hutcheson mainly follows Locke. The technicalities of the subject are passed lightly over, and the book is readable. It may be specially noticed that he distinguishes between the mental result and its verbal expression judgment-proposition, that he constantly employs the word "idea," and that he defines logical truth

Logical truth

Logical truth is one of the most fundamental concepts in logic, and there are different theories on its nature. A logical truth is a statement which is true and remains true under all reinterpretations of its components other than its logical constants. It is a type of analytic statement.Logical...

as "convenientia signorum cum rebus significatis" (or "propositionis convenientia cum rebus ipsis," Syn. Metaph. pars i. cap 3), thus implicitly repudiating a merely formal view of logic.

Aesthetics

Hutcheson may further be regarded as one of the earliest modern writers on aesthetics. His speculations on this subject are contained in the Inquiry concerning Beauty, Order, Harmony and Design, the first of the two treatises published in 1725. He maintains that we are endowed with a special sense by which we perceive beauty, harmony and proportion. This is a reflex sense, because it presupposes the action of the external senses of sight and hearing. It may be called an internal sense, both to distinguish its perceptions from the mere perceptions of sight and hearing, and because "in some other affairs, where our external senses are not much concerned, we discern a sort of beauty, very like in many respects to that observed in sensible objects, and accompanied with like pleasure" (Inquiry, etc., sect. 1, XI). The latter reason leads him to call attention to the beauty perceived in universal truths, in the operations of general causes and in moral principles and actions. Thus, the analogy between beauty and virtue, which was so favourite a topic with Shaftesbury, is prominent in the writings of Hutcheson also. Scattered up and down the treatise there are many important and interesting observations that our limits prevent us from noticing. But to the student of mental philosophy it may be specially interesting to remark that Hutcheson both applies the principle of association to explain our ideas of beauty and also sets limits to its application, insisting on there being "a natural power of perception or sense of beauty in objects, antecedent to all custom, education or example" (see Inquiry, etc., sects. 6, 7; Hamilton's Lectures on Metaphysics, Lect. 44 ad fin.).Hutcheson's writings naturally gave rise to much controversy. To say nothing of minor opponents, such as "Philaretus" (Gilbert Burnet, already alluded to), Dr John Balguy (1686–1748), prebendary of Salisbury, the author of two tracts on "The Foundation of Moral Goodness", and Dr John Taylor (1694–1761) of Norwich, a minister of considerable reputation in his time (author of An Examination of the Scheme of Amorality advanced by Dr Hutcheson), the essays appear to have suggested, by antagonism, at least two works that hold a permanent place in the literature of English ethics—Butler's Dissertation on the Nature of Virtue, and Richard Price

Richard Price

Richard Price was a British moral philosopher and preacher in the tradition of English Dissenters, and a political pamphleteer, active in radical, republican, and liberal causes such as the American Revolution. He fostered connections between a large number of people, including writers of the...

's Treatise of Moral Good and Evil (1757). In this latter work the author maintains, in opposition to Hutcheson, that actions are -in themselves right or wrong, that right and wrong are simple ideas incapable of analysis, and that these ideas are perceived immediately by the understanding. We thus see that, not only directly but also through the replies that it called forth, the system of Hutcheson, or at least the system of Hutcheson combined with that of Shaftesbury, contributed, in large measure, to the formation and development of some of the most important of the modern schools of ethics.

Later Scholarly Mention

References to Hutcheson occur in histories, both of general philosophy and of moral philosophy, as, for instance, in pt. vii. of Adam Smith's Theory of Moral Sentiments; MackintoshJames Mackintosh

Sir James Mackintosh was a Scottish jurist, politician and historian. His studies and sympathies embraced many interests. He was trained as a doctor and barrister, and worked also as a journalist, judge, administrator, professor, philosopher and politician.-Early life:Mackintosh was born at...

's Progress of Ethical Philosophy; Cousin

Victor Cousin

Victor Cousin was a French philosopher. He was a proponent of Scottish Common Sense Realism and had an important influence on French educational policy.-Early life:...

, Cours d'histoire de la philosophie morale du XVIII' siècle; Whewell's Lectures on the History of Moral Philosophy in England; A Bain

Alexander Bain

Alexander Bain was a Scottish philosopher and educationalist in the British school of empiricism who was a prominent and innovative figure in the fields of psychology, linguistics, logic, moral philosophy and education reform...

's Mental and Moral Science; Noah Porter

Noah Porter

Noah Porter, Jr. was an American academic, philosopher, author, lexicographer and President of Yale College .-Biography:...

's Appendix to the English translation of Ueberweg's History of Philosophy; Sir Leslie Stephen's History of English Thought in the Eighteenth Gentury, etc. See also Martineau

James Martineau

James Martineau was an English religious philosopher influential in the history of Unitarianism. For 45 years he was Professor of Mental and Moral Philosophy and Political Economy in Manchester New College, the principal training college for British Unitarianism.-Early life:He was born in Norwich,...

, Types of Ethical Theory (London, 1902); WR Scott, Francis Hutcheson (Cambridge, 1900); Albee, History of English Utilitarianism (London, 1902); T Fowler, Shaftesbury and Hutcheson (London, 1882); J McCosh

James McCosh

James McCosh was a prominent philosopher of the Scottish School of Common Sense. He was president of Princeton University 1868-1888.-Biography:...

, Scottish Philosophy (New York, 1874). Of Dr Leechman's Biography of Hutcheson we have already spoken. J. Veitch gives an interesting account of his professorial work in Glasgow, Mind, ii. 209-212.

Influence in Colonial America

Norman FieringNorman Fiering

Norman Fiering is an American historian, and Director and Librarian, Emeritus, of the John Carter Brown Library.-Life:...

, a specialist in the intellectual history of colonial New England, has described Francis Hutcheson as “probably the most influential and respected moral philosopher in America in the eighteenth century.” Hutcheson's early Inquiry into the Original of Our Ideas of Beauty and Virtue, introducing his perennial association of "unalienable rights" with the collective right to resist oppressive government, was used at Harvard College

Harvard College

Harvard College, in Cambridge, Massachusetts, is one of two schools within Harvard University granting undergraduate degrees...

as a textbook as early as the 1730s. In 1761, Hutcheson was publicly endorsed in the annual semi-official Massachusetts Election Sermon as "an approved writer on ethics." Hutcheson's Short Introduction to Moral Philosophy was used as a textbook at the College of Philadelphia in the 1760s. Francis Alison

Francis Alison

Francis Alison was a leading minister in the Synod of Philadelphia during The Old Side-New Side Controversy-Early life and education:...

, the professor of moral philosophy at the College of Philadelphia, was a former student of Hutcheson who closely followed Hutcheson’s thought. Alison's students included "a surprisingly large number of active, well-known patriots,” including three signers of the Declaration of Independence

Declaration of independence

A declaration of independence is an assertion of the independence of an aspiring state or states. Such places are usually declared from part or all of the territory of another nation or failed nation, or are breakaway territories from within the larger state...

, who "learned their patriotic principles from Hutcheson and Alison.” Another signer of the Declaration of Independence, John Witherspoon

John Witherspoon

John Witherspoon was a signatory of the United States Declaration of Independence as a representative of New Jersey. As president of the College of New Jersey , he trained many leaders of the early nation and was the only active clergyman and the only college president to sign the Declaration...

of the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University

Princeton University

Princeton University is a private research university located in Princeton, New Jersey, United States. The school is one of the eight universities of the Ivy League, and is one of the nine Colonial Colleges founded before the American Revolution....

), relied heavily on Hutcheson's views in his own lectures on moral philosophy. John Adams read Hutcheson's Short Introduction to Moral Philosophy shortly after graduating from Harvard. Garry Wills

Garry Wills

Garry Wills is a Pulitzer Prize-winning and prolific author, journalist, and historian, specializing in American politics, American political history and ideology and the Roman Catholic Church. Classically trained at a Jesuit high school and two universities, he is proficient in Greek and Latin...

argued in 1978 that the phrasing of the Declaration of Independence

Declaration of independence

A declaration of independence is an assertion of the independence of an aspiring state or states. Such places are usually declared from part or all of the territory of another nation or failed nation, or are breakaway territories from within the larger state...

was due largely to Hutcheson's influence, but Wills's work suffered a scathing rebuttal from Ronald Hamowy. Wills' view has been partially supported by Samuel Fleischacker, who agreed that it is "perfectly reasonable to see Hutcheson’s influence behind the appeals to sentiment that Jefferson put into his draft of the Declaration."

External links

- Francis Hutcheson at The Online Library of Liberty

- Contains versions of Origin of ideas of Beauty etc. and of Virtue etc., slightly modified for easier reading

----