Charles Stanhope, 3rd Earl Stanhope

Encyclopedia

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

statesman

Statesman

A statesman is usually a politician or other notable public figure who has had a long and respected career in politics or government at the national and international level. As a term of respect, it is usually left to supporters or commentators to use the term...

and scientist

Scientist

A scientist in a broad sense is one engaging in a systematic activity to acquire knowledge. In a more restricted sense, a scientist is an individual who uses the scientific method. The person may be an expert in one or more areas of science. This article focuses on the more restricted use of the word...

. He was the father of the great traveller and Arabist Lady Hester Stanhope

Lady Hester Stanhope

Lady Hester Lucy Stanhope , the eldest child of Charles Stanhope, 3rd Earl Stanhope by his first wife Lady Hester Pitt, is remembered by history as an intrepid traveller in an age when women were discouraged from being adventurous.-Early life and travels:Lady Hester was born and grew up at her...

and brother-in-law of William Pitt the Younger

William Pitt the Younger

William Pitt the Younger was a British politician of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. He became the youngest Prime Minister in 1783 at the age of 24 . He left office in 1801, but was Prime Minister again from 1804 until his death in 1806...

. He is sometimes confused with an exact contemporary of his, Charles Stanhope, 3rd Earl of Harrington

Charles Stanhope, 3rd Earl of Harrington

General Charles Stanhope, 3rd Earl of Harrington PC, PC , styled Viscount Petersham until 1779, was a British soldier. Stanhope is sometimes confused with an exact contemporary of his, the 3rd Earl Stanhope....

. His lean and awkward figure was extensively caricature

Caricature

A caricature is a portrait that exaggerates or distorts the essence of a person or thing to create an easily identifiable visual likeness. In literature, a caricature is a description of a person using exaggeration of some characteristics and oversimplification of others.Caricatures can be...

d by James Sayers

James Sayers

James Sayers was an English caricaturist.He was born at Great Yarmouth, Norfolk, the son of a merchant captain. He began as clerk in an attorney's office, and was for a time a member of the borough council. In 1780 his father's death provided him with a small fortune, and he went to London...

and James Gillray

James Gillray

James Gillray , was a British caricaturist and printmaker famous for his etched political and social satires, mainly published between 1792 and 1810.- Early life :He was born in Chelsea...

, reflecting his political opinions and his relationship with his children.

Early life

The son of the 2nd Earl StanhopePhilip Stanhope, 2nd Earl Stanhope

Philip Stanhope, 2nd Earl Stanhope FRS was a British peer.The son of the 1st Earl Stanhope and Lucy Pitt, he succeeded to his father's titles in 1721. He was a Fellow of the Royal Society....

, he was educated at Eton

Eton College

Eton College, often referred to simply as Eton, is a British independent school for boys aged 13 to 18. It was founded in 1440 by King Henry VI as "The King's College of Our Lady of Eton besides Wyndsor"....

and the University of Geneva

University of Geneva

The University of Geneva is a public research university located in Geneva, Switzerland.It was founded in 1559 by John Calvin, as a theological seminary and law school. It remained focused on theology until the 17th century, when it became a center for Enlightenment scholarship. In 1873, it...

. While in Geneva

Geneva

Geneva In the national languages of Switzerland the city is known as Genf , Ginevra and Genevra is the second-most-populous city in Switzerland and is the most populous city of Romandie, the French-speaking part of Switzerland...

, he devoted himself to the study of mathematics

Mathematics

Mathematics is the study of quantity, space, structure, and change. Mathematicians seek out patterns and formulate new conjectures. Mathematicians resolve the truth or falsity of conjectures by mathematical proofs, which are arguments sufficient to convince other mathematicians of their validity...

under Georges-Louis Le Sage

Georges-Louis Le Sage

Georges-Louis Le Sage was a physicist and is most known for his theory of gravitation, for his invention of an electric telegraph and his anticipation of the kinetic theory of gases....

, and acquired from Switzerland

Switzerland

Switzerland name of one of the Swiss cantons. ; ; ; or ), in its full name the Swiss Confederation , is a federal republic consisting of 26 cantons, with Bern as the seat of the federal authorities. The country is situated in Western Europe,Or Central Europe depending on the definition....

an intense love of liberty.

Politics

In politics he was a democratDemocracy

Democracy is generally defined as a form of government in which all adult citizens have an equal say in the decisions that affect their lives. Ideally, this includes equal participation in the proposal, development and passage of legislation into law...

. As Lord Mahon he contested the Westminster

Westminster (UK Parliament constituency)

Westminster was a parliamentary constituency in the Parliament of England to 1707, the Parliament of Great Britain 1707-1800 and the Parliament of the United Kingdom from 1801. It returned two members to 1885 and one thereafter....

without success in 1774, when only just of age; but from the general election of 1780 until his accession to the peerage on 7 March 1786 he represented through the influence of Lord Shelburne the Buckinghamshire

Buckinghamshire

Buckinghamshire is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan home county in South East England. The county town is Aylesbury, the largest town in the ceremonial county is Milton Keynes and largest town in the non-metropolitan county is High Wycombe....

borough of High Wycombe

Wycombe (UK Parliament constituency)

Wycombe is a parliamentary constituency represented in the House of Commons of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It currently elects one Member of Parliament by the first-past-the-post system of elections....

. During the sessions of 1783 and 1784 he supported William Pitt the Younger

William Pitt the Younger

William Pitt the Younger was a British politician of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. He became the youngest Prime Minister in 1783 at the age of 24 . He left office in 1801, but was Prime Minister again from 1804 until his death in 1806...

, whose sister, Lady Hester Pitt, he married on 19 December 1774. He was close enough to be singled out for ridicule in the Rolliad

Rolliad

The Rolliad, in full Criticisms on the Rolliad, is a pioneering work of British satire directed principally at the administration of William Pitt the Younger...

:

- ——This Quixote of the Nation

- Beats his own Windmills in gesticulation;

- To strike, not please, his utmost force he bends,

- And all his sense is at his fingers' ends, &c. &c.

When Pitt strayed from the Liberal

Liberalism in the United Kingdom

This article gives an overview of liberalism in the United Kingdom. It is limited to liberal parties with substantial support, mainly proved by having had a representation in parliament. The sign ⇒ denotes another party in that scheme...

principles of his early days, his brother-in-law severed their political connection and opposed the arbitrary measures which the ministry favoured. Lord Stanhope's character was generous, and his conduct consistent; but his speeches were not influential.

He was the chairman of the "Revolution Society," founded in honour of the Glorious Revolution

Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution, also called the Revolution of 1688, is the overthrow of King James II of England by a union of English Parliamentarians with the Dutch stadtholder William III of Orange-Nassau...

of 1688; the members of the society in 1790 expressed their sympathy with the aims of the French Revolution

French Revolution

The French Revolution , sometimes distinguished as the 'Great French Revolution' , was a period of radical social and political upheaval in France and Europe. The absolute monarchy that had ruled France for centuries collapsed in three years...

. In 1794 Stanhope supported Thomas Muir

Thomas Muir (radical)

Thomas Muir was a Scottish political reformer.Muir was the son of James Muir, a hop merchant, and was educated at Glasgow Grammar School, before attending the University of Glasgow to study divinity...

, one of the Edinburgh politicians who were transported to Botany Bay

Botany Bay

Botany Bay is a bay in Sydney, New South Wales, a few kilometres south of the Sydney central business district. The Cooks River and the Georges River are the two major tributaries that flow into the bay...

; and in 1795 he introduced into the Lords a motion deprecating any interference with the internal affairs of France. In all these points he was hopelessly beaten, and in the last of them he was in a "minority of one"—a sobriquet which stuck to him throughout life—whereupon he seceded from parliamentary life for five years.

Business, science and writing

University of Geneva

The University of Geneva is a public research university located in Geneva, Switzerland.It was founded in 1559 by John Calvin, as a theological seminary and law school. It remained focused on theology until the 17th century, when it became a center for Enlightenment scholarship. In 1873, it...

where he studied mathematics

Mathematics

Mathematics is the study of quantity, space, structure, and change. Mathematicians seek out patterns and formulate new conjectures. Mathematicians resolve the truth or falsity of conjectures by mathematical proofs, which are arguments sufficient to convince other mathematicians of their validity...

under Georges-Louis Le Sage

Georges-Louis Le Sage

Georges-Louis Le Sage was a physicist and is most known for his theory of gravitation, for his invention of an electric telegraph and his anticipation of the kinetic theory of gases....

. Electricity was another of the subjects which he studied, and the volume of Principles of Electricity which he issued in 1779 contained the rudiments of his theory on the "return stroke" resulting from the contact with the earth of the electric current of lightning, which were afterwards amplified in a contribution to the Philosophical Transactions for 1787. He was elected a fellow of the Royal Society

Royal Society

The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, known simply as the Royal Society, is a learned society for science, and is possibly the oldest such society in existence. Founded in November 1660, it was granted a Royal Charter by King Charles II as the "Royal Society of London"...

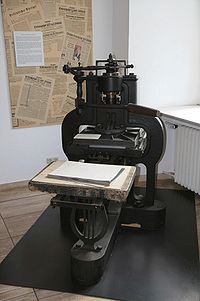

so early as November 1772, and devoted a large part of his income to experiments in science and philosophy. He invented a method of securing buildings from fire (which, however, proved impracticable), the printing press

Printing press

A printing press is a device for applying pressure to an inked surface resting upon a print medium , thereby transferring the ink...

and the lens

Lens (optics)

A lens is an optical device with perfect or approximate axial symmetry which transmits and refracts light, converging or diverging the beam. A simple lens consists of a single optical element...

which bear his name and a monochord

Monochord

A monochord is an ancient musical and scientific laboratory instrument. The word "monochord" comes from the Greek and means literally "one string." A misconception of the term lies within its name. Often a monochord has more than one string, most of the time two, one open string and a second string...

for tuning musical instruments, suggested improvements in canal locks, made experiments in steam navigation in 1795–1797 and contrived two calculating machine

Calculating machine

A calculating machine is a machine designed to come up with calculations or, in other words, computations. One noted machine was the Victorian British scientist Charles Babbage's Difference Engine , designed in the 1840s but never completed in the inventor's lifetime...

s.

When he acquired extensive property in Devon

Devon

Devon is a large county in southwestern England. The county is sometimes referred to as Devonshire, although the term is rarely used inside the county itself as the county has never been officially "shired", it often indicates a traditional or historical context.The county shares borders with...

, Stanhope projected a canal through that county from the Bristol

Bristol Channel

The Bristol Channel is a major inlet in the island of Great Britain, separating South Wales from Devon and Somerset in South West England. It extends from the lower estuary of the River Severn to the North Atlantic Ocean...

to the English Channel

English Channel

The English Channel , often referred to simply as the Channel, is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that separates southern England from northern France, and joins the North Sea to the Atlantic. It is about long and varies in width from at its widest to in the Strait of Dover...

and took the levels himself.

His principal labours in literature consisted of a reply to Edmund Burke

Edmund Burke

Edmund Burke PC was an Irish statesman, author, orator, political theorist and philosopher who, after moving to England, served for many years in the House of Commons of Great Britain as a member of the Whig party....

's Reflections on the French Revolution (1790) and an Essay on the rights of juries (1792), and he long meditated the compilation of a digest of the statutes.

Family and personal life

He married Lady Hester Pitt (19 October 1755 — 20 July 1780), daughter of Pitt the Elder, Prime Minister and 1st Earl of ChathamWilliam Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham

William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham PC was a British Whig statesman who led Britain during the Seven Years' War...

on 19 December 1774. They had three daughters:

- Lady Hester Lucy StanhopeLady Hester StanhopeLady Hester Lucy Stanhope , the eldest child of Charles Stanhope, 3rd Earl Stanhope by his first wife Lady Hester Pitt, is remembered by history as an intrepid traveller in an age when women were discouraged from being adventurous.-Early life and travels:Lady Hester was born and grew up at her...

(1776–1839) traveller and Arabist. Died aged 63, unmarried in SyriaSyriaSyria , officially the Syrian Arab Republic , is a country in Western Asia, bordering Lebanon and the Mediterranean Sea to the West, Turkey to the north, Iraq to the east, Jordan to the south, and Israel to the southwest....

. - Lady Griselda Stanhope (1778–1851) (married John Tickell).

- Lady Lucy Rachel Stanhope (1780–1814) who eloped with Thomas Taylor of SevenoaksSevenoaksSevenoaks is a commuter town situated on the London fringe of west Kent, England, some 20 miles south-east of Charing Cross, on one of the principal commuter rail lines from the capital...

, the family apothecary, and her father refused to be reconciled to her; but Pitt made her husband Controller-General of Customs and his son was one of the Earl of Chatham's executors.

Stanhope's first wife died in 1780.

In 1781 he married Louisa Grenville (1758–1829), daughter and sole heiress of the Hon. Henry Grenville

Henry Grenville

Henry Grenville was a British diplomat and politician.Grenville was the son of Richart Grenville born into a family of politicians, one of his elder brothers was Earl Temple, another a government minister, another was Lord of Trade and Cofferer of the Household, while another brother George...

(governor of Barbados

Barbados

Barbados is an island country in the Lesser Antilles. It is in length and as much as in width, amounting to . It is situated in the western area of the North Atlantic and 100 kilometres east of the Windward Islands and the Caribbean Sea; therein, it is about east of the islands of Saint...

in 1746 and ambassador to the Ottoman Porte in 1762), a younger brother of the 1st Earl Temple

Richard Temple-Nugent-Brydges-Chandos-Grenville, 1st Duke of Buckingham and Chandos

Richard Temple-Nugent-Brydges-Chandos-Grenville, 1st Duke of Buckingham and Chandos KG, PC , styled Earl Temple from 1784 to 1813 and known as The Marquess of Buckingham from 1813 to 1822, was a British landowner and politician.-Background:Born Richard Temple-Nugent-Grenville, he was the eldest son...

and of George Grenville. She survived him and died in March 1829. His second wife was the mother of two further sons. Together they had one son:

- Philip Henry Stanhope, 4th Earl Stanhope (1781–1855)

Lord Stanhope died at the family seat of Chevening

Chevening

Chevening, also known as Chevening House, is a country house at Chevening in the Sevenoaks District of Kent, in England. It is an official residence of the Foreign Secretary of the United Kingdom...

, Kent

Kent

Kent is a county in southeast England, and is one of the home counties. It borders East Sussex, Surrey and Greater London and has a defined boundary with Essex in the middle of the Thames Estuary. The ceremonial county boundaries of Kent include the shire county of Kent and the unitary borough of...

and was succeeded by his son who shared much of his father's scientific interest but is known also for his association with Kaspar Hauser

Kaspar Hauser

Kaspar Hauser was a German youth who claimed to have grown up in the total isolation of a darkened cell. Hauser's claims, and his subsequent death by stabbing, sparked much debate and controversy....

.