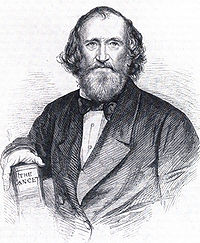

Thomas Wakley

Encyclopedia

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

surgeon

Surgeon

In medicine, a surgeon is a specialist in surgery. Surgery is a broad category of invasive medical treatment that involves the cutting of a body, whether human or animal, for a specific reason such as the removal of diseased tissue or to repair a tear or breakage...

. He became a demagogue and social reformer who campaigned against incompetence, privilege and nepotism. He was the founding editor of The Lancet

The Lancet

The Lancet is a weekly peer-reviewed general medical journal. It is one of the world's best known, oldest, and most respected general medical journals...

, and a radical Member of Parliament

Member of Parliament

A Member of Parliament is a representative of the voters to a :parliament. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, the term applies specifically to members of the lower house, as upper houses often have a different title, such as senate, and thus also have different titles for its members,...

(MP).

Life

Thomas Wakley was born in Membury, DevonMembury, Devon

Membury is a village three miles north west of Axminster in East Devon.The village has a 13th century church dedicated to St John the Baptist with a tall slim tower...

to a prosperous farmer and his wife. His father, Henry Wakley (1750–26 August 1842) inherited property, leased neighbouring land and became a large farmer by the standards of the day, and a government Commissioner on the Enclosure of Waste Land. He was described as a 'just but severe parent' and with his wife had eleven children, eight sons and three daughters. Thomas was the youngest son, and attended grammar schools at Chard

Chard, Somerset

Chard is a town and civil parish in the Somerset county of England. It lies on the A30 road near the Devon border, south west of Yeovil. The parish has a population of approximately 12,000 and, at an elevation of , it is the southernmost and highest town in Somerset...

and Taunton

Taunton

Taunton is the county town of Somerset, England. The town, including its suburbs, had an estimated population of 61,400 in 2001. It is the largest town in the shire county of Somerset....

. In his early teens he was apprenticed to a Taunton apothecary

Apothecary

Apothecary is a historical name for a medical professional who formulates and dispenses materia medica to physicians, surgeons and patients — a role now served by a pharmacist and some caregivers....

. Young Wakley was a sportsman, and a boxer: he fought bare-fisted in public houses.

He then went to London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

, where he attended anatomy classes at St Thomas's Hospital, and enrolled in the United Hospitals of St. Thomas's Hospital and Guy's

Guy's Hospital

Guy's Hospital is a large NHS hospital in the borough of Southwark in south east London, England. It is administratively a part of Guy's and St Thomas' NHS Foundation Trust. It is a large teaching hospital and is home to the King's College London School of Medicine...

. The dominant personality at these two hospitals was Sir Astley Cooper

Astley Cooper

Sir Astley Paston Cooper, 1st Baronet was an English surgeon and anatomist, who made historical contributions to otology, vascular surgery, the anatomy and pathology of the mammary glands and testicles, and the pathology and surgery of hernia.-Life:Cooper was born at Brooke Hall in Brooke, Norfolk...

FRS (1768–1841). Wakley qualified as a Member of the Royal College of Surgeons

Membership of the Royal College of Surgeons

MRCS is a professional qualification for surgeons in the UK and IrelandIt means Member of the Royal College of Surgeons. In the United Kingdom, doctors who gain this qualification traditionally no longer use the title 'Dr' but start to use the title 'Mr', 'Mrs', 'Miss' or 'Ms'.There are 4 surgical...

(MRCS) in 1817. A surgeon

Surgery

Surgery is an ancient medical specialty that uses operative manual and instrumental techniques on a patient to investigate and/or treat a pathological condition such as disease or injury, or to help improve bodily function or appearance.An act of performing surgery may be called a surgical...

at 22, he set up in practice in Regent Street

Regent Street

Regent Street is one of the major shopping streets in London's West End, well known to tourists and Londoners alike, and famous for its Christmas illuminations...

, and married (1820) Miss Goodchild, whose father was a merchant and a governor of St Thomas' Hospital

St Thomas' Hospital

St Thomas' Hospital is a large NHS hospital in London, England. It is administratively a part of Guy's & St Thomas' NHS Foundation Trust. It has provided health care freely or under charitable auspices since the 12th century and was originally located in Southwark.St Thomas' Hospital is accessible...

. They had three sons and a daughter, who died young. His eldest son, Henry Membury Wakley, became a barrister

Barrister

A barrister is a member of one of the two classes of lawyer found in many common law jurisdictions with split legal professions. Barristers specialise in courtroom advocacy, drafting legal pleadings and giving expert legal opinions...

, and sat as deputy Coroner under his father. His youngest son, James Goodchild Wakley and his middle son, Thomas Henry Wakley, became joint editors of The Lancet.

Arthur Thistlewood

Arthur Thistlewood was a British conspirator in the Cato Street Conspiracy.-Early life:He was born in Tupholme the extramarital son of a farmer and stockbreeder. He attended Horncastle Grammar School and was trained as a land surveyor. Unsatisfied with his job, he obtained a commission in the army...

) who had some imagined grievance against him burnt down his house and severely wounded him in a murderous assault. The whole affair is obscure. The assault may have been a follow-up to the Cato Street Conspiracy

Cato Street Conspiracy

The Cato Street Conspiracy was an attempt to murder all the British cabinet ministers and Prime Minister Lord Liverpool in 1820. The name comes from the meeting place near Edgware Road in London. The Cato Street Conspiracy is notable due to dissenting public opinions regarding the punishment of the...

, whose supporters believed (wrongly) that the hangman was a surgeon. Wakley was indirectly accused by the insurance company (which had refused his claim), of setting fire to his house himself. He won his case against the company.

Wakley's death, on 16 May 1862, was occasioned by pulmonary haemorrhage after a fall in Madeira

Madeira

Madeira is a Portuguese archipelago that lies between and , just under 400 km north of Tenerife, Canary Islands, in the north Atlantic Ocean and an outermost region of the European Union...

. He had been declining in health for about ten years, and the symptoms are entirely consistent with tuberculosis

Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis, MTB, or TB is a common, and in many cases lethal, infectious disease caused by various strains of mycobacteria, usually Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuberculosis usually attacks the lungs but can also affect other parts of the body...

. Wakley's three sons survived him, and the Lancet remained in Wakley hands for two more generations. At the funeral there was attendance from some of those whom he had pilloried: the long-term consequences of his radicalism were eventually appreciated, at least to some extent. Wakley is interred in the catacombs of Kensal Green Cemetery

Kensal Green Cemetery

Kensal Green Cemetery is a cemetery in Kensal Green, in the west of London, England. It was immortalised in the lines of G. K. Chesterton's poem The Rolling English Road from his book The Flying Inn: "For there is good news yet to hear and fine things to be seen; Before we go to Paradise by way of...

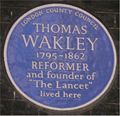

. There is a blue plaque

Blue plaque

A blue plaque is a permanent sign installed in a public place to commemorate a link between that location and a famous person or event, serving as a historical marker....

on his house in Bedford Square

Bedford Square

Bedford Square is a square in the Bloomsbury district of the Borough of Camden in London, England.Built between 1775 and 1783 as an upper middle class residential area, the sqare has had many distinguished residents, including Lord Eldon, one of Britain's longest serving and most celebrated Lord...

, London.

The Lancet years

In 1823 he started the now well-known medical weekly, The LancetThe Lancet

The Lancet is a weekly peer-reviewed general medical journal. It is one of the world's best known, oldest, and most respected general medical journals...

, with William Cobbett

William Cobbett

William Cobbett was an English pamphleteer, farmer and journalist, who was born in Farnham, Surrey. He believed that reforming Parliament and abolishing the rotten boroughs would help to end the poverty of farm labourers, and he attacked the borough-mongers, sinecurists and "tax-eaters" relentlessly...

, William Lawrence

Sir William Lawrence, 1st Baronet

Sir William Lawrence, 1st Baronet FRCS FRS was an English surgeon who became President of the Royal College of Surgeons of London and Serjeant Surgeon to the Queen....

, James Wardrop

James Wardrop

James Wardrop FRCSEd FRCS was a Scottish surgeon.Wardrop was born the youngest son of James and Marjorie Wardrop in Torbane Hill, Linlithgowshire but at four years of age moved with the family to live in Edinburgh where he attended Edinburgh High School...

and a libel lawyer as associates. It was extremely successful: by 1830 it had a circulation of about 4,000. In 1828, one of his accounts of medical negligence led to a libel case, Cooper v Wakley

Cooper v Wakley

Cooper v Wakley 172 ER 507 is an English tort law case, concerning the libel by the editor of The Lancet.-Facts:Thomas Wakley alleged in The Lancet that Bransby Cooper had negligently performed an operation on a patient. He alleged Bransby caused a patient incredible suffering as he attempted to...

, where Wakley accused Bransby Cooper, the nephew of the General Surgeon of incompetence in causing a patient immense suffering as he attempted to extract a bladder stone through a cut beneath the scrotum. After defending himself in a libel trial, Wakley lost, but the profile of the magazine was raised.

At first the editor of the Lancet was not named in the journal, but, after a few weeks rumours began to circulate. After the journal began printing the content of Sir Astley Cooper

Astley Cooper

Sir Astley Paston Cooper, 1st Baronet was an English surgeon and anatomist, who made historical contributions to otology, vascular surgery, the anatomy and pathology of the mammary glands and testicles, and the pathology and surgery of hernia.-Life:Cooper was born at Brooke Hall in Brooke, Norfolk...

's lectures without permission, the great man paid a surprise visit to his former pupil to discover Wakley correcting the proofs of the next issue. Upon recognizing each other, they fell immediately into laughter, or perhaps an altercation. Either way, they reached an agreement which was mutually satisfactory.

The libel lawyer was certainly needed, for the Lancet then was a campaigning journal, and began a series of attacks on the jobbery in vogue among the medical practitioners of the day. In opposition to the hospital surgeons and physicians he published reports of their lectures and exposed their malpractices. He had to fight a number of law-suits, which, however, only increased his influence. He attacked the whole constitution of the Royal College of Surgeons

Royal College of Surgeons of England

The Royal College of Surgeons of England is an independent professional body and registered charity committed to promoting and advancing the highest standards of surgical care for patients, regulating surgery, including dentistry, in England and Wales...

, and obtained so much support from among the general body of the profession, now roused to a sense of the abuses he exposed, that in 1827 a petition to Parliament resulted in a return being ordered of the public money granted to it.

- [We deplore the] "state of society which allows various sets of mercenary, goose-brained monopolists and charlatans to usurp the highest privileges.... This is the canker-worm which eats into the heart of the medical body" Wakley, The Lancet 1838–39, 1, p2–3.

- "The Council of the College of Surgeons remains an irresponsible, unreformed monstrosity in the midst of English institutions – an antediluvian relic of all... that is most despotic and revolting, iniquitous and insulting, on the face of the Earth". Wakley, The Lancet 1841–42, 2, p246.

He was especially severe on whomever he regarded as quacks. The English Homeopathic Association were "an audacious set of quacks" and its supporters "noodles and knaves, the noodles forming the majority, and the knaves using them as tools".

London College of Medicine

One of Wakley's best ideas came in 1831, when a series of massive meetings were held to launch a rival to the Royal Colleges. Though in the end not successful, the LCM incorporated ideas which formed the basis of reforms in the charters of the main licensing bodies, the Apothecaries, the Royal Colleges of Surgeons and Physicians.First, there was to be one Faculty: the LCM was to include physicians, surgeons and general practitioners; teachers at private medical schools and naval surgeons would also be included. Second, the structure was to be democratic: there would be no restrictions by religion (e.g. the Anglican restrictions of Oxford and Cambridge universities) or by institution (e.g. membership of hospitals). Its officers and Senate would be decided by annual ballot. The cost of diplomas would be set low; those already qualilfied would be eligible to become Fellows so, for instance, those qualified in Scotland would be received without reexamination. Appointments to official (public) positions were to be by merit, eliminating nepotism and the hand-placing of protégées. All Fellows would carry the prefix 'Dr', removing artificial divisions between members.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the LCM did not succeed against the united opposition of the established Colleges and other institutions. Nevertheless, the strong case for reform had been made in the most public manner. Subsequent legislation and reforms in governing charters were for many years influenced by this campaign.

Miscellany

In its early years the Lancet also had other content of a non-medical kind. There was a chessChess

Chess is a two-player board game played on a chessboard, a square-checkered board with 64 squares arranged in an eight-by-eight grid. It is one of the world's most popular games, played by millions of people worldwide at home, in clubs, online, by correspondence, and in tournaments.Each player...

column, the earliest regular chess column in any weekly periodical: The Chess Table. There were also occasional articles on politics, theatre reviews, biographies of non-medical persons, excerpts of material in other publications &c. None of this diminished its huge impact on surgery, hospitals and the Royal Colleges, which were opened up to public view as never before.

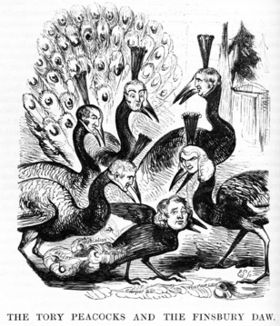

Member of Parliament

Reform in the College of Surgeons was slow, and Wakley now set himself to rouse the House of Commons from within. He became a radical candidate for ParliamentParliament of the United Kingdom

The Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the supreme legislative body in the United Kingdom, British Crown dependencies and British overseas territories, located in London...

, and in 1835 was returned for Finsbury

Finsbury (UK Parliament constituency)

The parliamentary borough of Finsbury was a constituency of the House of Commons of the Parliament of the United Kingdom from 1832 to 1885, and from 1918 to 1950. The constituency created in 1832 included part of the county of Middlesex north of the City of London and was named after the Finsbury...

, retaining his seat till 1852. Even after his departure, his work was largely responsible for the content of the Medical Act of 1858. He spoke in the House of Commons against Poor Laws, police bills, newspaper tax, Lord's Day

Lord's Day

Lord's Day is a Christian name for Sunday, the day of communal worship. It is observed by most Christians as the weekly memorial of the resurrection of Jesus Christ, who is said in the four canonical Gospels of the New Testament to have been witnessed alive from the dead early on the first day of...

observance and for Chartism

Chartism

Chartism was a movement for political and social reform in the United Kingdom during the mid-19th century, between 1838 and 1859. It takes its name from the People's Charter of 1838. Chartism was possibly the first mass working class labour movement in the world...

, Tolpuddle Martyrs

Tolpuddle Martyrs

The Tolpuddle Martyrs were a group of 19th century Dorset agricultural labourers who were arrested for and convicted of swearing a secret oath as members of the Friendly Society of Agricultural Labourers. The rules of the society show it was clearly structured as a friendly society and operated as...

, Free trade

Free trade

Under a free trade policy, prices emerge from supply and demand, and are the sole determinant of resource allocation. 'Free' trade differs from other forms of trade policy where the allocation of goods and services among trading countries are determined by price strategies that may differ from...

, Irish independence

Irish independence

Irish independence may refer to:* Irish War of Independence – a guerrilla war fought between the Irish Republican Army, under the Irish Republic, and the United Kingdom* Anglo-Irish Treaty – the treaty that brought the Irish War of Independence to a close...

and, of course, medical reform. All these topics were vigorously debated and fought over, for the 1830s was a turbulent decade; the origin of the difficulties lay in the massively expensive Napoleonic wars

Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars were a series of wars declared against Napoleon's French Empire by opposing coalitions that ran from 1803 to 1815. As a continuation of the wars sparked by the French Revolution of 1789, they revolutionised European armies and played out on an unprecedented scale, mainly due to...

, and in the inherent injustice of the way British law and Parliament

Parliament

A parliament is a legislature, especially in those countries whose system of government is based on the Westminster system modeled after that of the United Kingdom. The name is derived from the French , the action of parler : a parlement is a discussion. The term came to mean a meeting at which...

operated. The Chartist demands were 1. Universal suffrage for adult men 2. Annual Parliaments 3. Payment for members of Parliament 4. Abolition of property qualifications for candidates 5. Vote by ballot (i.e. secret voting) 6. Abolition of rotten boroughs (rough equalization of electoral districts). Apart from annual Parliaments (it is not feasible or sensible to have annual elections) all this was eventually achieved, and more, but it took time. The effect was to give ordinary citizens a direct say in how the country was governed (see also Democracy

Democracy

Democracy is generally defined as a form of government in which all adult citizens have an equal say in the decisions that affect their lives. Ideally, this includes equal participation in the proposal, development and passage of legislation into law...

). On this Wakley was one of many campaigners; his influence was greater than most because he was now inside Parliament.

Secularism

Secularism is the principle of separation between government institutions and the persons mandated to represent the State from religious institutions and religious dignitaries...

, but on his sympathy for the ordinary man. In his day, men worked a full six days each week, and could not shop on pay-nights. If all shops closed for the whole of Sunday this was clearly unfair to working men. Also, he advocated that places of education such as museums and zoos should be open to all on Sundays. The working week became 5-day around 1960, and it was even later before shops were able to open on Sundays.

Medical Coroner

Wakley also argued for medical coronerships, and when they were established he was elected CoronerCoroner

A coroner is a government official who* Investigates human deaths* Determines cause of death* Issues death certificates* Maintains death records* Responds to deaths in mass disasters* Identifies unknown dead* Other functions depending on local laws...

for West Middlesex

Middlesex

Middlesex is one of the historic counties of England and the second smallest by area. The low-lying county contained the wealthy and politically independent City of London on its southern boundary and was dominated by it from a very early time...

in 1839. Consistent with his views, he held inquests into any who died in police custody. He was indefatigable in upholding the interests of the working classes and advocating humanitarian reforms, as well as in pursuing his campaign against medical restrictions and abuses; and he made the Lancet not only a professional organ but a powerful engine of social reform.

Flogging

Wakley campaigned against flogging as a punishment for many years. Deaths from flogging in the British ArmyBritish Army

The British Army is the land warfare branch of Her Majesty's Armed Forces in the United Kingdom. It came into being with the unification of the Kingdom of England and Scotland into the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1707. The new British Army incorporated Regiments that had already existed in England...

were not unknown, and not surprising when one reads the details. Wakley was Coroner when Private James White, after committing a disciplinary offence, was subjected to 150 lashes of the cat-o'-nine-tails in the Seventh Hussars in 1846, and died a month later after symptoms of 'serious cardiac and pulmonary mischief' were followed by pleurisy and pneumonia. The army doctors, under direct pressure from the Colonel of the regiment, signed the certificate saying 'cause of death was in no way connected with the corporal punishment'. Before burial the vicar communicated with Wakley, who issued a warrant for an inquest. Evidence was given by the Army surgeons, and by the hospital physician and orderlies, and by independent experts. In the event, it was the evidence of Erasmus Wilson, consulting surgeon the St Pancras Infirmary, who made it clear that the flogging and the death were causally connected. The jury concurred, and added a strongly worded rider that expressed their 'horror and disgust that the law of the land provided that the revolting punishment of flogging should be permitted upon British soldiers'. Sprigge adds that it was not Erasmus Wilson's able scientific arguments which convinced the jury, it was his assertion that, had it not been for the flogging, James White would be alive. The Army Act of 1881 abolished flogging as a punishment.

Adulteration of foodstuffs

Wakley's last campaigns were against the adulteration of foodstuffs. This was far too common in his day, and his opposition was significant in bringing about much-needed reforming legislation. In order to provide evidence, Wakley set up The Lancet Analytical and Sanitary Commission, which provided 'records of the microscopical and chemical analyses of the solids and fluids consumed by all classes of the public'. The methods were devised by Wakley, Sir William Brooke O'ShaughnessyWilliam Brooke O'Shaughnessy

William Brooke O'Shaughnessy MD FRS was an Irish physician famous for his work in pharmacology and inventions related to telegraphy...

and Dr Arthur Hill Hassall

Arthur Hill Hassall

Arthur Hill Hassall was a British physician, chemist and microscopist who is primarily known for his work in public health and food safety....

, who was the Commissioner.

The first investigation showed that "it is a fact that coffee

Coffee

Coffee is a brewed beverage with a dark,init brooo acidic flavor prepared from the roasted seeds of the coffee plant, colloquially called coffee beans. The beans are found in coffee cherries, which grow on trees cultivated in over 70 countries, primarily in equatorial Latin America, Southeast Asia,...

is largely adulterated". Of 34 coffees, 31 were adulterated; the three exceptions were of higher price. The main adulteration was chicory

Chicory

Common chicory, Cichorium intybus, is a somewhat woody, perennial herbaceous plant usually with bright blue flowers, rarely white or pink. Various varieties are cultivated for salad leaves, chicons , or for roots , which are baked, ground, and used as a coffee substitute and additive. It is also...

, otherwise bean-flour, potato-flour or roasted corn was used. Moreover, it was found that chicory itself was usually adulterated. The Lancet published the names of the genuine traders, and threatened the others with exposure if they failed to mend their ways. A second report (26 April 1851) actually carried out this threat. A third report showed that canister coffee was even more adulterated. Investigations of sugar

Sugar

Sugar is a class of edible crystalline carbohydrates, mainly sucrose, lactose, and fructose, characterized by a sweet flavor.Sucrose in its refined form primarily comes from sugar cane and sugar beet...

, pepper

Black pepper

Black pepper is a flowering vine in the family Piperaceae, cultivated for its fruit, which is usually dried and used as a spice and seasoning. The fruit, known as a peppercorn when dried, is approximately in diameter, dark red when fully mature, and, like all drupes, contains a single seed...

, bread

Bread

Bread is a staple food prepared by cooking a dough of flour and water and often additional ingredients. Doughs are usually baked, but in some cuisines breads are steamed , fried , or baked on an unoiled frying pan . It may be leavened or unleavened...

, tobacco

Tobacco

Tobacco is an agricultural product processed from the leaves of plants in the genus Nicotiana. It can be consumed, used as a pesticide and, in the form of nicotine tartrate, used in some medicines...

, tea

Tea

Tea is an aromatic beverage prepared by adding cured leaves of the Camellia sinensis plant to hot water. The term also refers to the plant itself. After water, tea is the most widely consumed beverage in the world...

followed, and – most important of all – the purity of the water supply

Water supply

Water supply is the provision of water by public utilities, commercial organisations, community endeavours or by individuals, usually via a system of pumps and pipes...

. The first Adulteration Act became law in 1860, a second in 1872. The Sale of Food and Drugs Acts of 1875 and 1879 followed on. All this was achieved by Wakley and his associates.