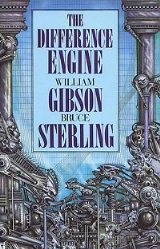

The Difference Engine

Encyclopedia

The Difference Engine is an alternate history novel by William Gibson

and Bruce Sterling

.

It posits a Victorian Britain

in which great technological and social change has occurred after entrepreneurial inventor Charles Babbage

succeeded in his ambition to build a mechanical computer

(actually his analytical engine

rather than the difference engine

).

The novel was nominated for the British Science Fiction Award in 1990, the Nebula Award for Best Novel

in 1991, and both the John W. Campbell Memorial Award and the Prix Aurora Award in 1992.

succeeded with his Difference Engine and went on to develop the Analytical Engine. He became politically powerful and at the 1830 general election

opposed the Tory Government of the Duke of Wellington

. Wellington staged a coup d'etat

in 1830 in an attempt to overturn his defeat and prevent the acceleration of technological change

and social upheaval, but was assassinated in 1831. So the Industrial Radical Party, led by a Lord Byron

who had not died in the Greek War of Independence

, came to power. The Tory Party and hereditary peerage were eclipsed. British trade unions assisted the ascendancy of the Industrial Radical Party (much as they aided the Labour Party

of Great Britain in the twentieth century in our own world). As a result, Luddite

anti-technological working class

revolutionaries were ruthlessly suppressed.

By 1855 the Babbage computers have become mass-produced and ubiquitous, and their use emulates the innovations which actually occurred during our information technology

and Internet

revolutions. Other steam powered technologies have also developed, so, for example, Gurney steam carriages are an increasingly common sight. The novel explores the social consequences of an information technology revolution in the nineteenth century, such as the emergence of "clackers" (a reference to hackers), technologically proficient people, such as Théophile Gautier

, who are skilled at programming the Engines through the use of punch-cards.

In the novel, the British Empire

is more powerful than in reality, thanks to the development and use of extremely advanced steam driven technology in industry. In addition, similar military technology has enhanced the capabilities of the armed forces (airships, dreadnoughts, and artillery); and the Babbage computers themselves. Under the Industrial Radical Party, Britain shows the utmost respect for leading scientific and industrial figures such as Isambard Kingdom Brunel

and Charles Darwin

. Indeed, they are collectively called "savants" and often raised to the peerage

on their merits

, causing a break with the past as regards social prestige and class distinction. These new patterns are also reflected in the educational sphere: classical studies have lost importance compared to more practical concerns such as engineering and accountancy.

Britain, rather than the United States

, opened Japan

to Western trade, in part because the United States became fragmented, due to interference from a Britain which foresaw the implications of a unified United States on the world stage. Counterpart successor states to our world's United States include: a (truncated) United States; the Confederate States of America

; the Republic of Texas

; the Republic of California; a Communist Manhattan

Island commune (with Karl Marx

as a leading light); British North America

(analogous to Canada

, albeit slightly larger in this world); Russian America (Alaska

); and terra nullius

. Napoleon III's French Empire

holds an entente with the British and Napoleon is even married to a British woman. In the world of The Difference Engine, it occupies Mexico

. Like Great Britain, it has its own analytical/difference engines (ordinateurs), especially used in the context of domestic surveillance

within its police force and intelligence agencies. As for the other world powers, Germany

remains fragmented, with no suggestion that Prussia

will eventually form the core of a unified nation as it did in our own world in 1871, which may be due to French sabotage analogous to that pursued in the case of the fragmentation of the United States noted above. As noted above, Japan

is awakening after the British ended its isolation, and looks set to become one of this world's leading industrial and economic powers from the twentieth century onward, as in our world. Due to Lords Byron and Babbage's intervention, the Irish potato famine never occurred, and as a result there is no mention of agitation for Irish home rule or Irish independence

.

Among other historical characters, the novel features "Texian

" President Sam Houston

, as an exile after a political coup in Texas

, a reference to Percy Bysshe Shelley

(as a Luddite

), John Keats

as a kinotropist (an operator of mechanical pixel

ated screens), and Benjamin Disraeli as a publicist and tabloid writer..

leader (she is borrowed from Disraeli's

novel Sybil

); Edward "Leviathan

" Mallory, a paleontologist

and explorer; and Laurence Oliphant, a historical figure with a real career, as portrayed in the book, as a travel writer whose work was a cover for espionage activities "undertaken in the service of Her Majesty". Linking all their stories is the trail of a mysterious set of reportedly very powerful computer punch card

s and the individuals fighting to obtain them; as is the case with special objects in several novels by Gibson, the punch cards are to some extent a MacGuffin

.

During the story, many characters come to believe that the punch cards are a gambling

"modus", a programme that would allow the user to place consistently winning bets. This is in line with Ada Lovelace

's historically documented penchant for gambling. Only in the last chapter is it revealed that the punched cards represent a program which proves two theorems which in reality would not be discovered until 1931 by Kurt Gödel

. Lovelace delivers a lecture on the subject in France.

Defending the cards, Mallory gathers his brothers and Ebenezer Fraser – a secret police officer – to fight the revolutionary Captain Swing

who leads a London riot during "the Stink", a major episode of pollution in which London swelters under an inversion layer

(comparable to the London Smog of December 1952

).

After the abortive uprising, Oliphant and Sybil Gerard meet at a cafe in Paris

. Oliphant informs her that he is aware of her true identity, but will not pursue it, although he does want information that would compromise her seducer, Charles Egremont MP, now regarded as an obstacle to the strategies and political ambitions of Lords Brunel and Babbage. Sybil has longed for an opportunity for vengeance against Egremont, and the resultant political scandal destroys his parliamentary career and aspirations for a merit lordship. Oliphant also encounters a Manhattan-based group of feminist pantomime artists.

After several vignettes that elaborate on the alternate historical origins of the world of The Difference Engine, Ada Lovelace delivers her lecture on Gödel's Theorem, as its counterpart is known in our world. She is chaperoned by Fraser, and castigated by Sybil Gerard, who is still unable to forgive Ada's father, the late Lord Byron, for his role in her own father's death.

At the very end of the novel, there is a dystopian depiction of an alternate 1991 from the vantage point of Ada Lovelace. Throughout the novel's latter sections, there are references to an "Eye". At the end of the novel, human beings appear to have become digitized, ephemeral ciphers at the mercy of a sentient artificial intelligence

.

; and Brian McHale

, who relates it to the postmodern interest in finding a "new way of 'doing' history in fiction."

The novel was nominated for the British Science Fiction Award in 1990, the Nebula Award for Best Novel

in 1991, and both the John W. Campbell Memorial Award and the Prix Aurora Award in 1992.

William Gibson

William Gibson is an American-Canadian science fiction author.William Gibson may also refer to:-Association football:*Will Gibson , Scottish footballer...

and Bruce Sterling

Bruce Sterling

Michael Bruce Sterling is an American science fiction author, best known for his novels and his work on the Mirrorshades anthology, which helped define the cyberpunk genre.-Writings:...

.

It posits a Victorian Britain

Victorian era

The Victorian era of British history was the period of Queen Victoria's reign from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. It was a long period of peace, prosperity, refined sensibilities and national self-confidence...

in which great technological and social change has occurred after entrepreneurial inventor Charles Babbage

Charles Babbage

Charles Babbage, FRS was an English mathematician, philosopher, inventor and mechanical engineer who originated the concept of a programmable computer...

succeeded in his ambition to build a mechanical computer

Computer

A computer is a programmable machine designed to sequentially and automatically carry out a sequence of arithmetic or logical operations. The particular sequence of operations can be changed readily, allowing the computer to solve more than one kind of problem...

(actually his analytical engine

Analytical engine

The Analytical Engine was a proposed mechanical general-purpose computer designed by English mathematician Charles Babbage. It was first described in 1837 as the successor to Babbage's difference engine, a design for a mechanical calculator...

rather than the difference engine

Difference engine

A difference engine is an automatic, mechanical calculator designed to tabulate polynomial functions. Both logarithmic and trigonometric functions can be approximated by polynomials, so a difference engine can compute many useful sets of numbers.-History:...

).

The novel was nominated for the British Science Fiction Award in 1990, the Nebula Award for Best Novel

Nebula Award for Best Novel

Winners of the Nebula Award for Best Novel, awarded by the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America. The stated year is that of publication; awards are given in the following year.- Winners and other nominees :...

in 1991, and both the John W. Campbell Memorial Award and the Prix Aurora Award in 1992.

Setting

The novel is chiefly set in 1855. The historical background diverges from reality around 1824, when it is imagined that Charles BabbageCharles Babbage

Charles Babbage, FRS was an English mathematician, philosopher, inventor and mechanical engineer who originated the concept of a programmable computer...

succeeded with his Difference Engine and went on to develop the Analytical Engine. He became politically powerful and at the 1830 general election

United Kingdom general election, 1830

The 1830 United Kingdom general election, was triggered by the death of King George IV and produced the first parliament of the reign of his successor, William IV. Fought in the aftermath of the Swing Riots, it saw electoral reform become a major election issue...

opposed the Tory Government of the Duke of Wellington

Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington

Field Marshal Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, KG, GCB, GCH, PC, FRS , was an Irish-born British soldier and statesman, and one of the leading military and political figures of the 19th century...

. Wellington staged a coup d'etat

Coup d'état

A coup d'état state, literally: strike/blow of state)—also known as a coup, putsch, and overthrow—is the sudden, extrajudicial deposition of a government, usually by a small group of the existing state establishment—typically the military—to replace the deposed government with another body; either...

in 1830 in an attempt to overturn his defeat and prevent the acceleration of technological change

Technological change

Technological change is a term that is used to describe the overall process of invention, innovation and diffusion of technology or processes. The term is synonymous with technological development, technological achievement, and technological progress...

and social upheaval, but was assassinated in 1831. So the Industrial Radical Party, led by a Lord Byron

George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron

George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron, later George Gordon Noel, 6th Baron Byron, FRS , commonly known simply as Lord Byron, was a British poet and a leading figure in the Romantic movement...

who had not died in the Greek War of Independence

Greek War of Independence

The Greek War of Independence, also known as the Greek Revolution was a successful war of independence waged by the Greek revolutionaries between...

, came to power. The Tory Party and hereditary peerage were eclipsed. British trade unions assisted the ascendancy of the Industrial Radical Party (much as they aided the Labour Party

Labour Party (UK)

The Labour Party is a centre-left democratic socialist party in the United Kingdom. It surpassed the Liberal Party in general elections during the early 1920s, forming minority governments under Ramsay MacDonald in 1924 and 1929-1931. The party was in a wartime coalition from 1940 to 1945, after...

of Great Britain in the twentieth century in our own world). As a result, Luddite

Luddite

The Luddites were a social movement of 19th-century English textile artisans who protested – often by destroying mechanised looms – against the changes produced by the Industrial Revolution, which they felt were leaving them without work and changing their way of life...

anti-technological working class

Working class

Working class is a term used in the social sciences and in ordinary conversation to describe those employed in lower tier jobs , often extending to those in unemployment or otherwise possessing below-average incomes...

revolutionaries were ruthlessly suppressed.

By 1855 the Babbage computers have become mass-produced and ubiquitous, and their use emulates the innovations which actually occurred during our information technology

Information technology

Information technology is the acquisition, processing, storage and dissemination of vocal, pictorial, textual and numerical information by a microelectronics-based combination of computing and telecommunications...

and Internet

Internet

The Internet is a global system of interconnected computer networks that use the standard Internet protocol suite to serve billions of users worldwide...

revolutions. Other steam powered technologies have also developed, so, for example, Gurney steam carriages are an increasingly common sight. The novel explores the social consequences of an information technology revolution in the nineteenth century, such as the emergence of "clackers" (a reference to hackers), technologically proficient people, such as Théophile Gautier

Théophile Gautier

Pierre Jules Théophile Gautier was a French poet, dramatist, novelist, journalist, art critic and literary critic....

, who are skilled at programming the Engines through the use of punch-cards.

In the novel, the British Empire

British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom. It originated with the overseas colonies and trading posts established by England in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. At its height, it was the...

is more powerful than in reality, thanks to the development and use of extremely advanced steam driven technology in industry. In addition, similar military technology has enhanced the capabilities of the armed forces (airships, dreadnoughts, and artillery); and the Babbage computers themselves. Under the Industrial Radical Party, Britain shows the utmost respect for leading scientific and industrial figures such as Isambard Kingdom Brunel

Isambard Kingdom Brunel

Isambard Kingdom Brunel, FRS , was a British civil engineer who built bridges and dockyards including the construction of the first major British railway, the Great Western Railway; a series of steamships, including the first propeller-driven transatlantic steamship; and numerous important bridges...

and Charles Darwin

Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin FRS was an English naturalist. He established that all species of life have descended over time from common ancestry, and proposed the scientific theory that this branching pattern of evolution resulted from a process that he called natural selection.He published his theory...

. Indeed, they are collectively called "savants" and often raised to the peerage

Peerage

The Peerage is a legal system of largely hereditary titles in the United Kingdom, which constitute the ranks of British nobility and is part of the British honours system...

on their merits

Meritocracy

Meritocracy, in the first, most administrative sense, is a system of government or other administration wherein appointments and responsibilities are objectively assigned to individuals based upon their "merits", namely intelligence, credentials, and education, determined through evaluations or...

, causing a break with the past as regards social prestige and class distinction. These new patterns are also reflected in the educational sphere: classical studies have lost importance compared to more practical concerns such as engineering and accountancy.

Britain, rather than the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

, opened Japan

Japan

Japan is an island nation in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean, it lies to the east of the Sea of Japan, China, North Korea, South Korea and Russia, stretching from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea and Taiwan in the south...

to Western trade, in part because the United States became fragmented, due to interference from a Britain which foresaw the implications of a unified United States on the world stage. Counterpart successor states to our world's United States include: a (truncated) United States; the Confederate States of America

Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America was a government set up from 1861 to 1865 by 11 Southern slave states of the United States of America that had declared their secession from the U.S...

; the Republic of Texas

Republic of Texas

The Republic of Texas was an independent nation in North America, bordering the United States and Mexico, that existed from 1836 to 1846.Formed as a break-away republic from Mexico by the Texas Revolution, the state claimed borders that encompassed an area that included all of the present U.S...

; the Republic of California; a Communist Manhattan

Manhattan

Manhattan is the oldest and the most densely populated of the five boroughs of New York City. Located primarily on the island of Manhattan at the mouth of the Hudson River, the boundaries of the borough are identical to those of New York County, an original county of the state of New York...

Island commune (with Karl Marx

Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx was a German philosopher, economist, sociologist, historian, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. His ideas played a significant role in the development of social science and the socialist political movement...

as a leading light); British North America

British North America

British North America is a historical term. It consisted of the colonies and territories of the British Empire in continental North America after the end of the American Revolutionary War and the recognition of American independence in 1783.At the start of the Revolutionary War in 1775 the British...

(analogous to Canada

Canada

Canada is a North American country consisting of ten provinces and three territories. Located in the northern part of the continent, it extends from the Atlantic Ocean in the east to the Pacific Ocean in the west, and northward into the Arctic Ocean...

, albeit slightly larger in this world); Russian America (Alaska

Alaska

Alaska is the largest state in the United States by area. It is situated in the northwest extremity of the North American continent, with Canada to the east, the Arctic Ocean to the north, and the Pacific Ocean to the west and south, with Russia further west across the Bering Strait...

); and terra nullius

Terra nullius

Terra nullius is a Latin expression deriving from Roman law meaning "land belonging to no one" , which is used in international law to describe territory which has never been subject to the sovereignty of any state, or over which any prior sovereign has expressly or implicitly relinquished...

. Napoleon III's French Empire

Second French Empire

The Second French Empire or French Empire was the Imperial Bonapartist regime of Napoleon III from 1852 to 1870, between the Second Republic and the Third Republic, in France.-Rule of Napoleon III:...

holds an entente with the British and Napoleon is even married to a British woman. In the world of The Difference Engine, it occupies Mexico

Mexico

The United Mexican States , commonly known as Mexico , is a federal constitutional republic in North America. It is bordered on the north by the United States; on the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; on the southeast by Guatemala, Belize, and the Caribbean Sea; and on the east by the Gulf of...

. Like Great Britain, it has its own analytical/difference engines (ordinateurs), especially used in the context of domestic surveillance

Surveillance

Surveillance is the monitoring of the behavior, activities, or other changing information, usually of people. It is sometimes done in a surreptitious manner...

within its police force and intelligence agencies. As for the other world powers, Germany

Germany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

remains fragmented, with no suggestion that Prussia

Prussia

Prussia was a German kingdom and historic state originating out of the Duchy of Prussia and the Margraviate of Brandenburg. For centuries, the House of Hohenzollern ruled Prussia, successfully expanding its size by way of an unusually well-organized and effective army. Prussia shaped the history...

will eventually form the core of a unified nation as it did in our own world in 1871, which may be due to French sabotage analogous to that pursued in the case of the fragmentation of the United States noted above. As noted above, Japan

Japan

Japan is an island nation in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean, it lies to the east of the Sea of Japan, China, North Korea, South Korea and Russia, stretching from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea and Taiwan in the south...

is awakening after the British ended its isolation, and looks set to become one of this world's leading industrial and economic powers from the twentieth century onward, as in our world. Due to Lords Byron and Babbage's intervention, the Irish potato famine never occurred, and as a result there is no mention of agitation for Irish home rule or Irish independence

Irish independence

Irish independence may refer to:* Irish War of Independence – a guerrilla war fought between the Irish Republican Army, under the Irish Republic, and the United Kingdom* Anglo-Irish Treaty – the treaty that brought the Irish War of Independence to a close...

.

Among other historical characters, the novel features "Texian

Texian

Texian is an archaic, mostly defunct 19th century demonym which defined a settler of current-day Texas, one of the southern states of the United States of America which borders the country of Mexico...

" President Sam Houston

Sam Houston

Samuel Houston, known as Sam Houston , was a 19th-century American statesman, politician, and soldier. He was born in Timber Ridge in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia, of Scots-Irish descent. Houston became a key figure in the history of Texas and was elected as the first and third President of...

, as an exile after a political coup in Texas

Texas

Texas is the second largest U.S. state by both area and population, and the largest state by area in the contiguous United States.The name, based on the Caddo word "Tejas" meaning "friends" or "allies", was applied by the Spanish to the Caddo themselves and to the region of their settlement in...

, a reference to Percy Bysshe Shelley

Percy Bysshe Shelley

Percy Bysshe Shelley was one of the major English Romantic poets and is critically regarded as among the finest lyric poets in the English language. Shelley was famous for his association with John Keats and Lord Byron...

(as a Luddite

Luddite

The Luddites were a social movement of 19th-century English textile artisans who protested – often by destroying mechanised looms – against the changes produced by the Industrial Revolution, which they felt were leaving them without work and changing their way of life...

), John Keats

John Keats

John Keats was an English Romantic poet. Along with Lord Byron and Percy Bysshe Shelley, he was one of the key figures in the second generation of the Romantic movement, despite the fact that his work had been in publication for only four years before his death.Although his poems were not...

as a kinotropist (an operator of mechanical pixel

Pixel

In digital imaging, a pixel, or pel, is a single point in a raster image, or the smallest addressable screen element in a display device; it is the smallest unit of picture that can be represented or controlled....

ated screens), and Benjamin Disraeli as a publicist and tabloid writer..

Plot summary

The action of the story follows Sybil Gerard, a political courtesan and daughter of an executed LudditeLuddite

The Luddites were a social movement of 19th-century English textile artisans who protested – often by destroying mechanised looms – against the changes produced by the Industrial Revolution, which they felt were leaving them without work and changing their way of life...

leader (she is borrowed from Disraeli's

Benjamin Disraeli, 1st Earl of Beaconsfield

Benjamin Disraeli, 1st Earl of Beaconsfield, KG, PC, FRS, was a British Prime Minister, parliamentarian, Conservative statesman and literary figure. Starting from comparatively humble origins, he served in government for three decades, twice as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom...

novel Sybil

Sybil (novel)

Sybil, or The Two Nations is an 1845 novel by Benjamin Disraeli. Published in the same year as Friedrich Engels's The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844, Sybil traces the plight of the working classes of England...

); Edward "Leviathan

Leviathan

Leviathan , is a sea monster referred to in the Bible. In Demonology, Leviathan is one of the seven princes of Hell and its gatekeeper . The word has become synonymous with any large sea monster or creature...

" Mallory, a paleontologist

Paleontology

Paleontology "old, ancient", ὄν, ὀντ- "being, creature", and λόγος "speech, thought") is the study of prehistoric life. It includes the study of fossils to determine organisms' evolution and interactions with each other and their environments...

and explorer; and Laurence Oliphant, a historical figure with a real career, as portrayed in the book, as a travel writer whose work was a cover for espionage activities "undertaken in the service of Her Majesty". Linking all their stories is the trail of a mysterious set of reportedly very powerful computer punch card

Punch card

A punched card, punch card, IBM card, or Hollerith card is a piece of stiff paper that contains digital information represented by the presence or absence of holes in predefined positions...

s and the individuals fighting to obtain them; as is the case with special objects in several novels by Gibson, the punch cards are to some extent a MacGuffin

MacGuffin

A MacGuffin is "a plot element that catches the viewers' attention or drives the plot of a work of fiction". The defining aspect of a MacGuffin is that the major players in the story are willing to do and sacrifice almost anything to obtain it, regardless of what the MacGuffin actually is...

.

During the story, many characters come to believe that the punch cards are a gambling

Gambling

Gambling is the wagering of money or something of material value on an event with an uncertain outcome with the primary intent of winning additional money and/or material goods...

"modus", a programme that would allow the user to place consistently winning bets. This is in line with Ada Lovelace

Ada Lovelace

Augusta Ada King, Countess of Lovelace , born Augusta Ada Byron, was an English writer chiefly known for her work on Charles Babbage's early mechanical general-purpose computer, the analytical engine...

's historically documented penchant for gambling. Only in the last chapter is it revealed that the punched cards represent a program which proves two theorems which in reality would not be discovered until 1931 by Kurt Gödel

Kurt Gödel

Kurt Friedrich Gödel was an Austrian logician, mathematician and philosopher. Later in his life he emigrated to the United States to escape the effects of World War II. One of the most significant logicians of all time, Gödel made an immense impact upon scientific and philosophical thinking in the...

. Lovelace delivers a lecture on the subject in France.

Defending the cards, Mallory gathers his brothers and Ebenezer Fraser – a secret police officer – to fight the revolutionary Captain Swing

Captain Swing

Captain Swing was the name appended to some of the threatening letters during the rural English Swing Riots of 1830, when labourers rioted over the introduction of new threshing machines and the loss of their livelihoods...

who leads a London riot during "the Stink", a major episode of pollution in which London swelters under an inversion layer

Inversion (meteorology)

In meteorology, an inversion is a deviation from the normal change of an atmospheric property with altitude. It almost always refers to a temperature inversion, i.e...

(comparable to the London Smog of December 1952

Great Smog of 1952

The Great Smog of '52 or Big Smoke was a severe air pollution event that affected London, England, during December 1952. A period of cold weather, combined with an anticyclone and windless conditions, collected airborne pollutants mostly from the use of coal to form a thick layer of smog over the...

).

After the abortive uprising, Oliphant and Sybil Gerard meet at a cafe in Paris

Paris

Paris is the capital and largest city in France, situated on the river Seine, in northern France, at the heart of the Île-de-France region...

. Oliphant informs her that he is aware of her true identity, but will not pursue it, although he does want information that would compromise her seducer, Charles Egremont MP, now regarded as an obstacle to the strategies and political ambitions of Lords Brunel and Babbage. Sybil has longed for an opportunity for vengeance against Egremont, and the resultant political scandal destroys his parliamentary career and aspirations for a merit lordship. Oliphant also encounters a Manhattan-based group of feminist pantomime artists.

After several vignettes that elaborate on the alternate historical origins of the world of The Difference Engine, Ada Lovelace delivers her lecture on Gödel's Theorem, as its counterpart is known in our world. She is chaperoned by Fraser, and castigated by Sybil Gerard, who is still unable to forgive Ada's father, the late Lord Byron, for his role in her own father's death.

At the very end of the novel, there is a dystopian depiction of an alternate 1991 from the vantage point of Ada Lovelace. Throughout the novel's latter sections, there are references to an "Eye". At the end of the novel, human beings appear to have become digitized, ephemeral ciphers at the mercy of a sentient artificial intelligence

Artificial intelligence

Artificial intelligence is the intelligence of machines and the branch of computer science that aims to create it. AI textbooks define the field as "the study and design of intelligent agents" where an intelligent agent is a system that perceives its environment and takes actions that maximize its...

.

Characters

- The character Michael Godwin was named after attorney Mike GodwinMike GodwinMichael Wayne Godwin is an American attorney and author. He was the first staff counsel of the Electronic Frontier Foundation , and the creator of the Internet adage Godwin's Law of Nazi Analogies. From July 2007 to October 2010, he was general counsel for the Wikimedia Foundation...

as thanks for his technical assistance in linking Sterling and Gibson's computers to allow them to collaborate between Austin and Vancouver.

Literary criticism and significance

The novel has attracted the attention of scholars, including Jay Clayton, who explores the book's attitude toward hacking, as well as its treatment of Babbage and Ada Lovelace; Herbert Sussman, who demonstrates how the book rewrites Benjamin Disraeli's novel SybilSybil (novel)

Sybil, or The Two Nations is an 1845 novel by Benjamin Disraeli. Published in the same year as Friedrich Engels's The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844, Sybil traces the plight of the working classes of England...

; and Brian McHale

Brian McHale

Brian G. McHale is an American literary theorist who writes on a range of fiction and poetics, mainly those relating to postmodernism and narrative theory.-Career:...

, who relates it to the postmodern interest in finding a "new way of 'doing' history in fiction."

The novel was nominated for the British Science Fiction Award in 1990, the Nebula Award for Best Novel

Nebula Award for Best Novel

Winners of the Nebula Award for Best Novel, awarded by the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America. The stated year is that of publication; awards are given in the following year.- Winners and other nominees :...

in 1991, and both the John W. Campbell Memorial Award and the Prix Aurora Award in 1992.

External links

- The Difference Dictionary, an indexed addendum of topics discussed in the novel, compiled by Eileen GunnEileen GunnEileen Gunn is a science fiction author and editor based in Seattle, Washington, who began publishing in 1978....

- Editions of The Difference Engine at WorldcatWorldCatWorldCat is a union catalog which itemizes the collections of 72,000 libraries in 170 countries and territories which participate in the Online Computer Library Center global cooperative...

.org - The Difference Engine at Worlds Without End

- Review at Infinity-plus

- "Gibson and Sterling's Alternative History: The Difference Engine as Radical Rewriting of Disraeli's Sybil"