Serjeant-at-law

Encyclopedia

Barrister

A barrister is a member of one of the two classes of lawyer found in many common law jurisdictions with split legal professions. Barristers specialise in courtroom advocacy, drafting legal pleadings and giving expert legal opinions...

s at the English

England and Wales

England and Wales is a jurisdiction within the United Kingdom. It consists of England and Wales, two of the four countries of the United Kingdom...

bar

Bar (law)

Bar in a legal context has three possible meanings: the division of a courtroom between its working and public areas; the process of qualifying to practice law; and the legal profession.-Courtroom division:...

. The position of Serjeant-at-Law (servientes ad legem), or Sergeant-Counter, was centuries old; there are writs dating to 1300 which identify them as descended from figures in France prior to the Norman Conquest. The Serjeants were the oldest formally created order in England, having been brought into existence as a body by Henry II

Henry II of England

Henry II ruled as King of England , Count of Anjou, Count of Maine, Duke of Normandy, Duke of Aquitaine, Duke of Gascony, Count of Nantes, Lord of Ireland and, at various times, controlled parts of Wales, Scotland and western France. Henry, the great-grandson of William the Conqueror, was the...

. The order rose during the 16th century as a small, elite group of lawyers who took much of the work in the central common law courts. With the creation of Queen's Counsel

Queen's Counsel

Queen's Counsel , known as King's Counsel during the reign of a male sovereign, are lawyers appointed by letters patent to be one of Her [or His] Majesty's Counsel learned in the law...

(or "Queen's Counsel Extraordinary") during the reign of Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I of England

Elizabeth I was queen regnant of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death. Sometimes called The Virgin Queen, Gloriana, or Good Queen Bess, Elizabeth was the fifth and last monarch of the Tudor dynasty...

, the order gradually began to decline, with each monarch opting to create more King's or Queen's Counsel. The Serjeants' exclusive jurisdictions were ended during the 19th century, and with the Judicature Act 1873 coming into force in 1875, it was felt that there was no need to have such figures, and no more were created. The last English Serjeant-at-Law was Lord Lindley

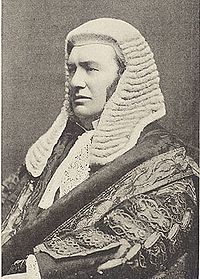

Nathaniel Lindley, Baron Lindley

Sir Nathaniel Lindley, Baron Lindley SL PC FRS was an English judge.-Biography:He was the second son of the botanist John Lindley, born at Acton Green, London. He was educated at University College School, and studied for a time at University College, London...

; with his death in 1921 the order ceased to exist. The last Irish serjeant was A. M. Sullivan.

The Serjeants had for many centuries exclusive jurisdiction over the Court of Common Pleas

Court of Common Pleas (England)

The Court of Common Pleas, or Common Bench, was a common law court in the English legal system that covered "common pleas"; actions between subject and subject, which did not concern the king. Created in the late 12th to early 13th century after splitting from the Exchequer of Pleas, the Common...

, being the only lawyers allowed to bring a case there. At the same time they had rights of audience in the other central common law courts (the Court of King's Bench

Court of King's Bench (England)

The Court of King's Bench , formally known as The Court of the King Before the King Himself, was an English court of common law in the English legal system...

and Exchequer of Pleas

Exchequer of pleas

The Exchequer of Pleas or Court of Exchequer was a court that followed equity, a set of legal principles based on natural law, and common law, in England and Wales. Originally part of the curia regis, or King's Council, the Exchequer of Pleas split from the curia during the 1190s, to sit as an...

) and precedence over all other lawyers. Only Serjeants-at-Law could become judges of these courts right up into the 19th century, and socially the Serjeants ranked above Knights Bachelor and Companions of the Bath. Within the Serjeants-at-Law were more distinct orders; the King's Serjeants, particularly favoured Serjeants-at-Law, and within that the King's Premier Serjeant, the Monarch's most favoured Serjeant, and the King's Ancient Serjeant, the oldest. Serjeants (except King's Serjeants) were created by Writ of Summons under the Great Seal of the Realm

Great Seal of the Realm

The Great Seal of the Realm or Great Seal of the United Kingdom is a seal that is used to symbolise the Sovereign's approval of important state documents...

and wore a special and distinctive dress, the chief feature of which was the coif

Coif

A coif is a close fitting cap that covers the top, back, and sides of the head.- History :Coifs were worn by all classes in England and Scotland from the Middle Ages to the early seventeenth century .Tudor and earlier coifs are usually made of unadorned white linen and tied under...

, a white lawn or silk

Silk

Silk is a natural protein fiber, some forms of which can be woven into textiles. The best-known type of silk is obtained from the cocoons of the larvae of the mulberry silkworm Bombyx mori reared in captivity...

skull cap, afterwards represented by a round piece of white lace at the top of the wig.

Early history

The history of Serjeants-at-Law goes back centuries; Alexander Pulling argues that Serjeants-at-Law existed "before any large portion of our law was formed", and Edward Warren agrees, supporting him with a Norman writ from approximately 1300 which identifies Serjeants-at-Law as directly descending from Norman conteurs; indeed, they were sometimes known as Serjeant-Conteurs. The members of the Order initially used St Paul's CathedralSt Paul's Cathedral

St Paul's Cathedral, London, is a Church of England cathedral and seat of the Bishop of London. Its dedication to Paul the Apostle dates back to the original church on this site, founded in AD 604. St Paul's sits at the top of Ludgate Hill, the highest point in the City of London, and is the mother...

as their meeting place, standing near the "parvis" where they would give counsel to those who sought advice. Geoffrey Chaucer

Geoffrey Chaucer

Geoffrey Chaucer , known as the Father of English literature, is widely considered the greatest English poet of the Middle Ages and was the first poet to have been buried in Poet's Corner of Westminster Abbey...

makes reference to the Serjeants in the Canterbury Tales, writing:

A serjeant of the law, ware and wise,

That often hadde ben at the parvis,

Ther was also, full rich of excellence.

Discreet he was and of great reverence,

He sened swiche; his wordes were so wise,

Justice he was ful often in assise,

By patent, and by pleine commissiun;

For his science, and for his high renoun,

Of fees and robes had he many on.

The Order certainly existed during the reign of Henry II

Henry II of England

Henry II ruled as King of England , Count of Anjou, Count of Maine, Duke of Normandy, Duke of Aquitaine, Duke of Gascony, Count of Nantes, Lord of Ireland and, at various times, controlled parts of Wales, Scotland and western France. Henry, the great-grandson of William the Conqueror, was the...

from 1154–1189, who created a dozen Serjeants and thus moved the order's existence "out of the realm of conjecture" and into recorded fact. As such it is the oldest royally created order; the next is the Order of the Garter

Order of the Garter

The Most Noble Order of the Garter, founded in 1348, is the highest order of chivalry, or knighthood, existing in England. The order is dedicated to the image and arms of St...

, created in 1330. Serjeants at Law existed in Ireland from at least 1302, and were appointed by letters patent

Letters patent

Letters patent are a type of legal instrument in the form of a published written order issued by a monarch or president, generally granting an office, right, monopoly, title, or status to a person or corporation...

in a similar way to English Serjeants. Henry de Bracton

Henry de Bracton

Henry of Bracton, also Henry de Bracton, also Henrici Bracton, or Henry Bratton also Henry Bretton was an English jurist....

claimed that, for the trial of Hubert de Burgh

Hubert de Burgh, 1st Earl of Kent

Hubert de Burgh, 1st Earl of Kent was Earl of Kent, Justiciar of England and Ireland, and one of the most influential men in England during the reigns of John and Henry III.-Birth and family:...

in 1239 the king was assisted by "all the serjeants of the bench", although it is not known who they were. By the 1270s there were approximately 20 recorded Serjeants; by 1290, 36. This period also saw the first regulation of Serjeants, with a statutory power from 1275 to suspend from practise any Serjeant who misbehaved. The exclusive jurisdiction Serjeants-at-Law held over the Court of Common Pleas

Court of Common Pleas (England)

The Court of Common Pleas, or Common Bench, was a common law court in the English legal system that covered "common pleas"; actions between subject and subject, which did not concern the king. Created in the late 12th to early 13th century after splitting from the Exchequer of Pleas, the Common...

slowly came about during the 1320s, squeezing the size of the bar until only a consistent group reappeared. From this period, Serjeants also began to be called in regular groups, rather than individually on whatever date was felt appropriate.

Rise

During the 16th century the Serjeants-at-Law were a small, though highly respected and powerful, elite. There were never more than ten alive, and on several occasions the number dwindled to one; William Blendlowes bragged that he had been "the only Serjeant-at-Law in England" in 1559. Over 100 years, only 89 were created. At the time they were the only clearly distinguishable branch of the legal profession, and it is thought that their work may have actually created barristerBarrister

A barrister is a member of one of the two classes of lawyer found in many common law jurisdictions with split legal professions. Barristers specialise in courtroom advocacy, drafting legal pleadings and giving expert legal opinions...

s as a separate group; although Serjeants were the only lawyers who normally argued in court, they occasionally allowed other lawyers to help them in special cases. These lawyers became known as outer or "utter" barristers (because they were confined to the outer bar of the court); if they were allowed to act they had "passed the bar" towards becoming a Serjeant-at-Law.

Despite holding a monopoly on cases in the Court of Common Pleas

Court of Common Pleas (England)

The Court of Common Pleas, or Common Bench, was a common law court in the English legal system that covered "common pleas"; actions between subject and subject, which did not concern the king. Created in the late 12th to early 13th century after splitting from the Exchequer of Pleas, the Common...

, Serjeants also took most of the business in the Court of King's Bench

Court of King's Bench (England)

The Court of King's Bench , formally known as The Court of the King Before the King Himself, was an English court of common law in the English legal system...

. Although required to make the Common Pleas their principal place of work, there is evidence of Serjeants who did not; one, Robert Mennell, worked entirely in the North of England after his creation in 1547 and was not known in Westminster, where the Common Pleas was located. This was also a time of great judicial success for the Serjeants; since only Serjeants could be appointed to the common law courts, many also sat in the Exchequer of Pleas

Exchequer of pleas

The Exchequer of Pleas or Court of Exchequer was a court that followed equity, a set of legal principles based on natural law, and common law, in England and Wales. Originally part of the curia regis, or King's Council, the Exchequer of Pleas split from the curia during the 1190s, to sit as an...

, a court of equity. This period was not a time of success for the profession overall, however, despite the brisk business being done. The rise of central courts other than the Common Pleas allowed for other lawyers to get advocacy experience and work, drawing it away from the Serjeants, and at the same time the small number of Serjeants were insufficient to handle all the business in the Common Pleas, allowing the rise of barristers as dedicated advocates.

Decline and abolition

The decline of the Serjeants-at-Law started in 1596, when Francis BaconFrancis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Albans, KC was an English philosopher, statesman, scientist, lawyer, jurist, author and pioneer of the scientific method. He served both as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England...

persuaded Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I of England

Elizabeth I was queen regnant of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death. Sometimes called The Virgin Queen, Gloriana, or Good Queen Bess, Elizabeth was the fifth and last monarch of the Tudor dynasty...

to appoint him "Queen's Counsel Extraordinary" (QC), a new creation which gave him precedence over the Serjeants. This was not a formal creation, in that he was not granted a patent of appointment, but in 1604 James I

James I of England

James VI and I was King of Scots as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the English and Scottish crowns on 24 March 1603...

saw fit to finally award this. The creation of Queen's (or King's) Counsel was initially small; James I created at least one other, and Charles I

Charles I of England

Charles I was King of England, King of Scotland, and King of Ireland from 27 March 1625 until his execution in 1649. Charles engaged in a struggle for power with the Parliament of England, attempting to obtain royal revenue whilst Parliament sought to curb his Royal prerogative which Charles...

four. Following the English Restoration

English Restoration

The Restoration of the English monarchy began in 1660 when the English, Scottish and Irish monarchies were all restored under Charles II after the Interregnum that followed the Wars of the Three Kingdoms...

this increased, with a few appointed each year. The largest change came about with William IV

William IV of the United Kingdom

William IV was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and of Hanover from 26 June 1830 until his death...

, who appointed an average of nine a year, and following him approximately 12 were created a year, with an average of 245 at any one time.

Every new Queen's Counsel created reduced the Serjeants in importance, since even the most junior QC took precedence over the most senior Serjeant. Although appointments were still made to the Serjeants-at-Law, the King's Serjeant and the King's Ancient Serjeant, and several Serjeants were granted patents of precedence which gave them superiority over QCs, the Victorian era saw a decline in appointments. The rule that all common law judges must be Serjeants was also flouted; it was decided this simply meant that anyone appointed as a judge would quickly be appointed a Serjeant, and then immediately a judge. In 1834 Lord Brougham

Henry Brougham, 1st Baron Brougham and Vaux

Henry Peter Brougham, 1st Baron Brougham and Vaux was a British statesman who became Lord Chancellor of Great Britain.As a young lawyer in Scotland Brougham helped to found the Edinburgh Review in 1802 and contributed many articles to it. He went to London, and was called to the English bar in...

issued a mandate which opened up pleading in the Court of Common Pleas

Court of Common Pleas (England)

The Court of Common Pleas, or Common Bench, was a common law court in the English legal system that covered "common pleas"; actions between subject and subject, which did not concern the king. Created in the late 12th to early 13th century after splitting from the Exchequer of Pleas, the Common...

to every barrister

Barrister

A barrister is a member of one of the two classes of lawyer found in many common law jurisdictions with split legal professions. Barristers specialise in courtroom advocacy, drafting legal pleadings and giving expert legal opinions...

, Serjeant or not, and this was followed for six years until the Serjeants successfully petitioned the Queen to overturn it as invalid.

The Serjeants only enjoyed their returned status for another six years, however, before Parliament intervened. The Practitioners in Common Pleas Act 1846, from 18 August 1846, allowed all barristers to practice in the Court of Common Pleas. The next and final blow was the Judicature Act 1873, which came into force on 1 November 1875. Section 8 provided that common law judges no longer be appointed from the Serjeants-at-Law, removing the need to appoint judicial Serjeants. With this Act and the rise of the Queen's Counsel, there was no longer any need to appoint Serjeants, and the practice ended. The order ceased to exist on the death of Lord Lindley

Nathaniel Lindley, Baron Lindley

Sir Nathaniel Lindley, Baron Lindley SL PC FRS was an English judge.-Biography:He was the second son of the botanist John Lindley, born at Acton Green, London. He was educated at University College School, and studied for a time at University College, London...

, the last Serjeant appointed and the last Serjeant alive, in 1921.

Serjeant's Inn

Serjeant's Inn was an Inn of CourtInns of Court

The Inns of Court in London are the professional associations for barristers in England and Wales. All such barristers must belong to one such association. They have supervisory and disciplinary functions over their members. The Inns also provide libraries, dining facilities and professional...

restricted to Serjeants-at-Law. It operated from three locations, one in Holborn, known as Scroope's Inn, which was abandoned by 1498 for the one in Fleet Street, which was pulled down during the 18th century, and one on Chancery Lane, pulled down in 1877. The Inn was a voluntary association, and although most Serjeants joined upon being appointed they were not required to. There were rarely more than 40 Serjeants, even including members of the judiciary, and the Inns were noticeably smaller than the Inns of Court. Unlike the Inns of Court, Serjeant's Inn was a private establishment similar to a gentlemen's club

Gentlemen's club

A gentlemen's club is a members-only private club of a type originally set up by and for British upper class men in the eighteenth century, and popularised by English upper-middle class men and women in the late nineteenth century. Today, some are more open about the gender and social status of...

.

The Inn on Fleet Street existed from at least 1443, when it was rented from the Dean of York. By the 16th century it had become the main Inn, before being burnt down during the Great Fire of London

Great Fire of London

The Great Fire of London was a major conflagration that swept through the central parts of the English city of London, from Sunday, 2 September to Wednesday, 5 September 1666. The fire gutted the medieval City of London inside the old Roman City Wall...

. It was rebuilt by 1670, but the end finally came in 1733. The Fleet Street Inn had fallen into a "ruinous state", and the Serjeants had been unable to obtain a renewal of their lease. They abandoned the property, and it returned to the Dean.

The property on Chancery Lane consisted of a Hall, dining room, a library, kitchens and offices for the Serjeants-at-Law. This Inn was originally known as "Skarle's Inn" from about 1390, named after John Scarle

John Scarle

John Scarle was keeper of the rolls of Chancery from 1394 to 1397 and Archdeacon of Lincoln before being named Lord Chancellor of England in 1399. He held that office until 9 March 1401.-References:...

, who became Master of the Rolls

Master of the Rolls

The Keeper or Master of the Rolls and Records of the Chancery of England, known as the Master of the Rolls, is the second most senior judge in England and Wales, after the Lord Chief Justice. The Master of the Rolls is the presiding officer of the Civil Division of the Court of Appeal...

in 1394. By 1404 it was known as "Farringdon's Inn", but although the Serjeants were in full possession by 1416 it was not until 1484 that the property became known as Serjeant's Inn. Newly promoted Serjeants had to pay £350 in the 19th century, while those promoted solely to take up judicial office had to pay £500. The Hall was a large room hung with portraits of various famous judges and Serjeants-at-Law, with three windows on one side each containing the coat of arms of a distinguished judge. Around the room were the coats of arms of various Serjeants, which were given to their descendants when the Inn was finally sold. When the Fleet Street Inn was abandoned, this location became the sole residence of the Serjeants. With the demise of the order after the Judicature Act 1873, there was no way to support the Inn, and it was sold in 1877 for £57,100. The remaining Serjeants were accepted into their former Inns of Court

Inns of Court

The Inns of Court in London are the professional associations for barristers in England and Wales. All such barristers must belong to one such association. They have supervisory and disciplinary functions over their members. The Inns also provide libraries, dining facilities and professional...

, where judicial Serjeants were made Bencher

Bencher

A bencher or Master of the Bench is a senior member of an Inn of Court in England and Wales. Benchers hold office for life once elected. A bencher can be elected while still a barrister , in recognition of the contribution that the barrister has made to the life of the Inn or to the law...

s and normal Serjeants barristers.

Call to the Coif

The process of being called to the order of Serjeants-at-Law stayed fairly constant. The traditional method was that the Serjeants would discuss among themselves prospective candidates, and then make recommendations to the Chief Justice of the Common PleasChief Justice of the Common Pleas

The Court of Common Pleas, also known as the Common Bench or Common Place, was the second highest common law court in the English legal system until 1880, when it was dissolved. As such, the Chief Justice of the Common Pleas was one of the highest judicial officials in England, behind only the Lord...

. He would pass these names on to the Lord Chancellor

Lord Chancellor

The Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain, or Lord Chancellor, is a senior and important functionary in the government of the United Kingdom. He is the second highest ranking of the Great Officers of State, ranking only after the Lord High Steward. The Lord Chancellor is appointed by the Sovereign...

, who would appoint the new Serjeants. This was intended to provide a way to select possible judges in a period where political favouritism was rampant - since only Serjeants could become judges, making sure that Serjeants were not political appointees was seen to provide for a neutral judiciary. Serjeants were traditionally appointed by a writ directly from the King. The writ was issued under the Great Seal of the Realm

Great Seal of the Realm

The Great Seal of the Realm or Great Seal of the United Kingdom is a seal that is used to symbolise the Sovereign's approval of important state documents...

and required "the elected and qualified apprentices of the law to take the state and degree of a Serjeant-at-Law". The newly created Serjeants would then assemble in one of the Inns of Court

Inns of Court

The Inns of Court in London are the professional associations for barristers in England and Wales. All such barristers must belong to one such association. They have supervisory and disciplinary functions over their members. The Inns also provide libraries, dining facilities and professional...

, where they would hear a speech from the Lord Chancellor

Lord Chancellor

The Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain, or Lord Chancellor, is a senior and important functionary in the government of the United Kingdom. He is the second highest ranking of the Great Officers of State, ranking only after the Lord High Steward. The Lord Chancellor is appointed by the Sovereign...

or Lord Chief Justice and be given a purse of gold. The Coif was then placed on the Serjeant's head. The Serjeants were required to swear an oath, which was that they would:

"serve the King's people as one of the Serjeants-at-law, and you shall truly counsel them that you be retained with after your cunning; and you shall not defer or delay their causes willingly, for covetness of money, or other thing that may turn you to profit; and you shall give due attendance accordingly. So help you God."

The new Serjeants would give a feast to celebrate, and gave out rings to their close friends and family to mark the occasion. The King, the Lord Chancellor

Lord Chancellor

The Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain, or Lord Chancellor, is a senior and important functionary in the government of the United Kingdom. He is the second highest ranking of the Great Officers of State, ranking only after the Lord High Steward. The Lord Chancellor is appointed by the Sovereign...

and other figures also received rings. The major courts would be suspended for the day, and the other Serjeants, judges, leaders of the Inns of Court

Inns of Court

The Inns of Court in London are the professional associations for barristers in England and Wales. All such barristers must belong to one such association. They have supervisory and disciplinary functions over their members. The Inns also provide libraries, dining facilities and professional...

and occasionally the King would attend. Serjeant's Inn

Serjeant's Inn

Serjeant's Inn was one of the two inns of the Serjeants-at-Law in London. The Fleet Street inn dated from 1443 and the Chancery Lane inn dated from 1416. Both buildings were destroyed in the World War II 1941 bombing raids....

and the Inns of Court

Inns of Court

The Inns of Court in London are the professional associations for barristers in England and Wales. All such barristers must belong to one such association. They have supervisory and disciplinary functions over their members. The Inns also provide libraries, dining facilities and professional...

were not big enough for such an occasion, and Ely Place

Ely Place

Ely Place is a gated road at the southern tip of the London Borough of Camden in London, England. It is the location of the Old Mitre Tavern and is adjacent to Hatton Garden.-Origins:...

or Lambeth Palace

Lambeth Palace

Lambeth Palace is the official London residence of the Archbishop of Canterbury in England. It is located in Lambeth, on the south bank of the River Thames a short distance upstream of the Palace of Westminster on the opposite shore. It was acquired by the archbishopric around 1200...

would instead be used. The feasts gradually declined in importance, and by the 17th century they were small enough to be held in the Inns. The last recorded feast was in 1736 in Middle Temple

Middle Temple

The Honourable Society of the Middle Temple, commonly known as Middle Temple, is one of the four Inns of Court exclusively entitled to call their members to the English Bar as barristers; the others being the Inner Temple, Gray's Inn and Lincoln's Inn...

, when fourteen new Serjeants were raised to the Coif.

Robes

.jpg)

Coif

A coif is a close fitting cap that covers the top, back, and sides of the head.- History :Coifs were worn by all classes in England and Scotland from the Middle Ages to the early seventeenth century .Tudor and earlier coifs are usually made of unadorned white linen and tied under...

, a robe and a furred cloak. The robe and cloak were later adapted into the robe worn by judges. The cut and colour of this robe varied - records from the King's Privy Wardrobe show judges being instructed to wear robes of scarlet, green, purple and miniver

Miniver

*Miniver is an unspotted white fur derived from the stoat, and with particular use in the robes of peers. For the use of the fur in heraldry, see Ermine and Tincture *For the fictional character, see Mrs. Miniver...

, and Serjeants being ordered to wear the same. In 1555 new Serjeants were required to have robes of scarlet, brown, blue, mustard and murrey

Murrey

In heraldry, murrey is a "stain", an occasionally used tincture.According to dictionaries, murrey is the colour of mulberries, somewhere between gules and purpure , almost maroon; but examples registered in Canada and Scotland show it as a reddish brown.The Flag of the Second Spanish Republic was...

. By the time the order came to an end the formal robes were red, but Mr. Serjeant Robinson recalled that, towards the end days of the order, black silk gowns were the everyday court garb and the red gown was worn only on certain formal occasions. The cape was originally a cloak worn separately from the robe, but gradually made its way into the uniform as a whole. John Fortescue described the cape as the "main ornament of the order", distinguished only from the cape worn by judges because it was furred with lambskin rather than minever. The capes were not worn into court by the advocates, only by the serjeants.

The Coif was the main symbol of the Order of Serjeants-at-Law, and is where their most recognisable name (the Order of the Coif) comes from. The Coif was white and made of either silk or lawn

Lawn cloth

Lawn cloth or lawn is a plain weave textile, originally of linen but now chiefly cotton. Lawn is designed using fine, high count yarns, which results in a silky, untextured feel. The fabric is made using either combed or carded yarns. When lawn is made using combed yarns, with a soft feel and...

. A Serjeant was never obliged to take off or cover his Coif, not even in the presence of the King, except as a judge when passing a death sentence. In that situation he would wear a Black Cap

Black Cap

In English law, the black cap was worn by a judge when passing a sentence of death. Although it is called a "cap", it is not made to fit the head like a typical cap does; instead it is a simple plain square made of black fabric...

intended to cover the Coif, although it is often confused with the coif itself. When wigs were first introduced for barristers and judges it caused some difficulty for Serjeants, who were not allowed to cover the Coif. Wigmakers got around this by adding a small white cloth to the top of the wig, representing the Coif.

King's Serjeants

A King's Serjeant was a Serjeant-at-Law appointed to serve the CrownThe Crown

The Crown is a corporation sole that in the Commonwealth realms and any provincial or state sub-divisions thereof represents the legal embodiment of governance, whether executive, legislative, or judicial...

as a legal adviser to the monarch and their government in the same way as the Attorney-General for England and Wales. The King's Serjeant (who had the postnominal KS, or QS during the reign of a female monarch) would represent the Crown in court, acting as prosecutors in criminal cases and representatives in civil ones, and would have higher powers and ranking in the lower courts than the Attorney- or Solicitor General. King's Serjeants also worked as legal advisers in the House of Lords

House of Lords

The House of Lords is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster....

, and were not allowed to act in cases against the Crown or do anything that would harm it; in 1540 Serjeant Browne was heavily punished for creating a tax avoidance scheme. The King's Serjeants would wear a black Coif with a narrow strip of white, unlike the all-white Coif of a normal Serjeant. The King's Serjeants were required to swear a second oath to serve "The King and his people", rather than "The King's people" as a Serjeant-at-Law would swear. The King's favoured Serjeant would become the King's Premier Serjeant, while the oldest one was known as the King's Ancient Serjeant.

Precedence, status and rights of audience

For almost all of their history, Serjeants at Law and King's Serjeants were the only advocates given rights of audienceRights of audience

In common law, a right of audience is generally a right of a lawyer to appear and conduct proceedings in court on behalf of their client. In English law, there is a fundamental distinction between barristers, who have a right of audience, and solicitors, who traditionally do not ; there is no such...

in the Court of Common Pleas

Court of Common Pleas (England)

The Court of Common Pleas, or Common Bench, was a common law court in the English legal system that covered "common pleas"; actions between subject and subject, which did not concern the king. Created in the late 12th to early 13th century after splitting from the Exchequer of Pleas, the Common...

. Until the 17th century they were also first in the order of precedence in the Court of King's Bench

Court of King's Bench (England)

The Court of King's Bench , formally known as The Court of the King Before the King Himself, was an English court of common law in the English legal system...

and Court of Chancery

Court of Chancery

The Court of Chancery was a court of equity in England and Wales that followed a set of loose rules to avoid the slow pace of change and possible harshness of the common law. The Chancery had jurisdiction over all matters of equity, including trusts, land law, the administration of the estates of...

, which gave them priority in motions before the court. Serjeants also had the privilege of being immune from most normal forms of lawsuit - they could only be sued by a writ from the Court of Chancery. It was held as an extension of this that servants of Serjeants could only be sued in the Common Pleas. As part of the Court of Common Pleas the Serjeants also performed some judicial duties, such as levying fines. In exchange for these privileges, Serjeants were expected to fulfil certain duties; firstly, that they represent anybody who asked regardless of their ability to pay, and secondly that, due to the small number of judges, they serve as deputy judges to hear cases when there was no judge available.

Only Serjeants-at-Law could become judges of the common law courts; this rule came into being in the 14th century for the Courts of Common Pleas and King's Bench, and was extended to the Exchequer of Pleas

Exchequer of pleas

The Exchequer of Pleas or Court of Exchequer was a court that followed equity, a set of legal principles based on natural law, and common law, in England and Wales. Originally part of the curia regis, or King's Council, the Exchequer of Pleas split from the curia during the 1190s, to sit as an...

in the 16th century; it did not apply to the Court of Chancery

Court of Chancery

The Court of Chancery was a court of equity in England and Wales that followed a set of loose rules to avoid the slow pace of change and possible harshness of the common law. The Chancery had jurisdiction over all matters of equity, including trusts, land law, the administration of the estates of...

, a court of equity, or the Ecclesiastical Courts. The Serjeants-at-Law also had social privileges; they ranked above Knights Bachelor and Companions of the Bath, and their wives had the right to be addressed as "Lady -", in the same way as the wives of Knights or Baronet

Baronet

A baronet or the rare female equivalent, a baronetess , is the holder of a hereditary baronetcy awarded by the British Crown...

s. A Serjeant made a King's Counsel or judge would still retain these social privileges. As the cream of the legal profession, Serjeants earned higher fees than normal barristers.

In the order of precedence

Order of precedence

An order of precedence is a sequential hierarchy of nominal importance of items. Most often it is used in the context of people by many organizations and governments...

King's Serjeants came before all other barristers, even the Attorney General for England and Wales, until the introduction of King's Counsel. This state of affairs came to an end as a result of two changes - firstly, during the reign of James I

James I of England

James VI and I was King of Scots as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the English and Scottish crowns on 24 March 1603...

, when a royal patent gave the Attorney General precedence over all King's Serjeants "except the two ancientiest", and secondly in 1814 when the Attorney General of the time was a barrister and the Solicitor General (politically junior to the Attorney General) a King's Serjeant. To reflect the political reality, the Attorney General was made superior to any King's Serjeant, and this remained until the order of Serjeants-at-Law finally died out.