Rachel Chiesley, Lady Grange

Encyclopedia

Rachel Chiesley, usually known as Lady Grange (1679–1745), was the wife of James Erskine, Lord Grange, a Scottish

lawyer with Jacobite

sympathies. After 25 years of marriage and 9 children, the Granges had an acrimonious separation. After Lady Grange produced letters that she claimed were evidence of his treason

able plottings against the Hanoverian

government in London, her husband had her kidnapped in 1732. She was incarcerated in various remote locations on the western seaboard of Scotland, including the Monach Isles, Skye

and the distant islands of St Kilda

.

Lady Grange's father was convicted of murder and she is known to have had a violent temper; initially her absence seems to have caused little comment. News of her plight eventually reached her home town of Edinburgh

however, and an unsuccessful rescue attempt was effected by her lawyer, Thomas Hope of Rankeillor. She died in captivity, after being in effect imprisoned for 13 years. Her life has been remembered in poetry, prose and a play.

and Margaret Nicholson. The marriage was unhappy and Margaret took her husband to court for alimony

. She was awarded 1,700 merks by Sir George Lockhart of Carnwath

, the Lord President of the Court of Session

. Furious with the result, John Chiesley shot Lockhart dead on the Royal Mile

in Edinburgh

as he walked home from church on Easter Sunday, 31 March 1689. The assailant made no attempt to escape and confessed at his trial, held before the Lord Provost

the next day. Two days later he was taken from the Tolbooth

to the Mercat Cross on the High Street. His right hand was cut off before he was hanged, and the pistol he had used for the murder was placed round his neck. Chiesley's birthday is unknown but she was baptised on 4 February 1679 and was probably born shortly before then, making her about ten years old at the time of her father's execution.

The date of Chiesley's marriage to James Erskine is uncertain: based on the text of a letter she wrote much later in life, it may have been in 1707 when she was about 28. Erskine was the younger son of Charles Erskine, Earl of Mar

The date of Chiesley's marriage to James Erskine is uncertain: based on the text of a letter she wrote much later in life, it may have been in 1707 when she was about 28. Erskine was the younger son of Charles Erskine, Earl of Mar

and in 1689 his older brother John Erskine

, had already inherited the title of the 11th Earl of Mar

on their father's death. These were politically troubled times; the Jacobite cause was still popular in many parts of Scotland, and the younger Earl was nicknamed "Bobbing John" for his varied manoeuverings. After playing a prominent role in the Jacobite rebellion of 1715 he was stripped of his title, sent into exile

, and never returned to Scotland.

The young Lady Grange has been described as a "wild beauty", and it is likely the marriage only took place after she became pregnant. This uncertain background notwithstanding, Lord and Lady Grange led a superficially uneventful domestic life. They divided their time between a town house at the foot of Niddry's Wynd off the High Street in Edinburgh and an estate at Preston

(near Prestonpans

in East Lothian

), where Lady Grange was the factor

(or supervisor) for a time. Her husband was a successful lawyer, becoming Lord Justice Clerk

in 1710, and the marriage produced nine children:

In addition, Lady Grange miscarried

twice and one of the above children is known to have died in 1721.

However, there was an element of discord below the surface. In late 1717 or early 1718, Erskine received warnings from a friend that he had enemies in the government. At about the same time one of the children's tutors recorded in his diary that Lady Grange was "imperious with an unreasonable temper". Her outbursts were evidently also capable of frightening her younger daughters and it is a remarkable aspect of the story that no action was ever taken by any of Lady Grange's children on her behalf after her kidnapping, the eldest of whom would have been in their early twenties when she was abducted. This may become easier to understand with the knowledge that their mother had previously disinherited all of them, when the youngest were still infants.

to London and James Erskine and his friends, afraid her presence there would cause them further trouble, decided it was time to take decisive action.

She was abducted from her home on the night of 22 January by two Highland

She was abducted from her home on the night of 22 January by two Highland

noblemen, Roderick MacLeod of Berneray

and Macdonald of Morar

and several of their men. After a bloody struggle, she was taken out of the city in a sedan chair

and then on horseback to Wester Polmaise near Falkirk

, where she was held until 15 August on the ground floor of an uninhabited tower. She was by now over fifty years old.

From there she was taken west by Peter Fraser (a page of Lord Lovat

) and his men through Perthshire. At Balquhidder

, according to MacGregor tradition, she was entertained in the great hall, provided with a meal of venison, and slept on a heather bed covered with deerskins. The existence of St Fillan's

Pool on the River Fillan near Tyndrum

would have provided useful cover for her captors: it was regularly used as a cure for insanity, which would have helped to explain her presence to the curious. The details of the onward route from there are not clear but it is likely she was taken through Glen Coe

to Loch Ness

and then through Glen Garry to Loch Hourn

on the west coast. After a short delay she was then put on board ship to the Monach Isles. The difficulty of her position must have quickly become evident. She was in the company of men whose loyalty was to clan chieftains rather than the law, and few of them spoke any English at all. Their native Gaelic would have been incomprehensible to her, although as her years of captivity wore on she slowly learned something of the language. She complained that young members of the local aristocracy visited her as she waited by the shores of Loch Hourn, but that "they came with design to see me, but not to relieve me".

in the Outer Hebrides

, an archipelago itself lying off the western coast of Scotland. The main islands are Ceann Ear

, Ceann Iar

and Shivinish, which are all linked at low tide and have a combined area of 357 hectares (882.2 acre). The islands are low-lying and fertile, and their population in the 18th century may have been about 100. At the time they were owned by Sir Alexander MacDonald of Sleat

, and Lady Grange was housed with his tacksman

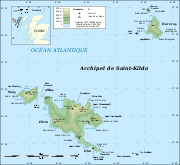

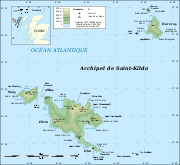

, another Alexander MacDonald, and his wife. When she complained about her condition, she was told by her host that he had no orders to provide her with either clothes, or food other than the normal fare he and his wife were used to. She lived in isolation for two years, not even being told the name of the island where she was living, and it took her some time to find out who her landlord was. She was there until June 1734, when John and Norman MacLeod from North Uist arrived to move her on. They told her they were taking her to Orkney, but instead set sail for the Atlantic outliers of St Kilda.

in the St Kilda archipelago is the site of Lady Grange's House. The "house" is in fact a large cleit or stone storage hut in the Village meadows which is said to resemble "a giant Christmas pudding". Some authorities believe it was rebuilt on the site of a larger black house

where she lived during her incarceration there, although in 1838 the grandson of a St Kildan who had assisted her quoted the dimensions as being "20 feet by 10 feet" (7 metres by 3 metres), which is roughly the size of the cleit.

Hirta is an order of magnitude more remote than the Monach Isles, lying 66 kilometres (41 mi) west-northwest of Benbecula

in the North Atlantic Ocean and the predominant theme of life on St Kilda was isolation. When Martin Martin

visited the islands in 1697, the only means of making the journey was by open longboat, which could take several days and nights of rowing and sailing across the open ocean and was next to impossible in autumn and winter. In all seasons, waves up to 12 metres (40 ft) high lash the beach of Village Bay, and even on calmer days landing on the slippery rocks can be hazardous. Cut off by distance and weather, the natives knew little of the rest of the world.

Lady Grange's circumstances were correspondingly more uncomfortable. She described Hirta as "a viled neasty, stinking poor Isle" and insisted that "I was in great miserie in the Husker but I'm ten times worse and worse here". Her lodgings were very primitive. They had an earthen floor, rain ran down the walls and in winter snow had to be scooped out in handfuls from behind the bed. She spent her days asleep, drank as much whisky as was available to her, and wandered the shore at night bemoaning her fate. During her sojourn on Hirta she wrote two letters relating her story, which eventually reached Edinburgh. One, dated 20 January 1738, found its way to Thomas Hope of Rankeillor, her lawyer, in December 1740. The letter caused a sensation in Edinburgh but James Erskine's friends managed to block attempts by Hope to obtain a warrant to search St Kilda.

In the second letter, addressed to Dr Carlyle, minister of Inveresk

In the second letter, addressed to Dr Carlyle, minister of Inveresk

, Lady Grange writes bitterly of the roles of Lord Lovat and Roderick McLeod in her capture and bemoans being described by Sir Alexander MacDonald as "the cargo". Hope had known of Lady Grange's removal from Edinburgh but had assumed she would be well cared for. Appalled by her condition, he paid for a sloop

with twenty armed men on board to go to St Kilda at his own expense. It had already set sail by 14 February 1741, but it arrived too late. Lady Grange had been removed from the island, probably in the summer of 1740.

After the Battle of Culloden

in 1746, it was rumoured that Prince Charles Edward Stuart and some of his senior Jacobite

aides had escaped to St Kilda. An expedition was launched, and in due course British soldiers were ferried ashore to Hirta. They found a deserted village, as the St Kildans, fearing pirates, had fled to caves to the west. When they were persuaded to come down, the soldiers discovered that the isolated natives knew nothing of the Prince and had never heard of King George II

either. Paradoxically, Lady Grange's letters and her resultant evacuation from the island, may have prevented her being found by this expedition.

including possibly Assynt

in the far north west of mainland Scotland and the Outer Hebridean locations of Harris and Uist

before arriving at Waternish

on Skye in 1742. Local folklore suggests she may have been kept for 18 months in a cave either at Idrigill

on the Trotternish

peninsula or on the Duirinish

coast near the stacks

known as a "Macleod's Maidens". She was certainly later housed with Rory MacNeil at Trumpan

in Waternish. She died there on 12 May 1745, and MacNeil had her "decently interred" the following week in the local churchyard. For reasons unknown a second funeral was held at nearby Duirinish some time thereafter, where a large crowd gathered to watch the burial of a coffin filled with turf and stones.

It is sometimes stated that this was her third funeral, Lord Grange having conducted one in Edinburgh shortly after her kidnapping. However, this story first appears in writing in 1845 and no other evidence of its existence has emerged.

The first and second questions are related. Erskine's brother had already been exiled for his support of the Jacobites. Simon Fraser, Lord Lovat, a key figure in Lady Grange's abduction was himself executed for his part in the Jacobite Rising of 1745

. No concrete evidence of Erskine's plotting against the crown or government has ever emerged, but any threat of such exposure, whether based in fact or fantasy would certainly have been taken very seriously by all concerned. It was thus relatively easy for Erskine to find accomplices amongst the Highland gentry. In addition to Simon Fraser and Alexander Macdonald of Sleat

, the Sobieski Stuarts (two English brothers who claimed descent from Prince Charles Edward Stuart) listed Norman MacLeod of Dunvegan

—who became known as "The Wicked Man"—as the senior accomplices.

Erskine himself was a "singular compound of good and bad qualities". In addition to his legal career he was elected to Parliament in 1734 and he survived the vicissitudes of the Jacobite rebellions unscathed. It is also clear that he was a philanderer and over-partial to claret

, whilst at the same time deeply religious. This last quality would have been instrumental in any decision not to have his wife assassinated, and he did not marry his long-term partner Fanny Lindsay until after he had heard of the first Lady Grange's death.

The third question is perhaps the easiest to answer. The Hebrides

were very remote from the anglophone

world in the early 18th century and no reliable naval charts of the area became available until 1776. Without local assistance and knowledge, finding a captive in this wilderness would have required a significant expeditionary force. Nonetheless, the lack of action taken by Edinburgh society in general and her children in particular to retrieve one of their own is remarkable. The Kirk

hierarchy, for example, made no attempt to contact her or convey news of her condition to the capital, yet they could easily have done so. Whatever the call of morality and natural justice may have suggested, it is clear that John Chiesley's daughter did not command a sympathetic audience in her home town.

There is also little doubt that 18th-century attitudes to women in general were a significant factor. Divorces were complex and divorced mothers were rarely given custody of children. Something of James Erskine's attitude to these matters may perhaps be gleaned from the fact that for his first speech in the House of Commons

he chose to oppose the repeal of various laws relating to witchcraft

. Even in his day this appeared unduly conservative and his perorations were met with laughter, which effectively ended his political career before it had begun. Writing in the mid-19th century the Sobieski Stuarts told the tale from the perspective of the descendants of the Highland aristocrats who had been responsible for Chiesley's kidnap and imprisonment. They emphasise Lady Grange's personal shortcomings, although to modern sensibilities these hardly seem good reasons for a judge and Member of Parliament

and his wealthy friends to organise an illegal kidnapping and life sentence.

As for Lady Grange herself, her vituperative outbursts and indulgence in alcohol were clearly important factors in her undoing. Alexander Carlyle

described her as "stormy and outrageous", whilst noting that it was in her husband's interests to exaggerate the nature of her violent emotions. Macauley (2009) takes the view that the ultimate cause of her troubles was her reaction to her husband's infidelity. In an attempt to end his relationship with Mrs Lindsay, (who owned a coffee house in Haymarket, Edinburgh

), Rachel threatened to expose him as a Jacobite sympathiser. Perhaps she did not understand the magnitude of this accusation and the danger it posed to her husband and his friends, or how ruthless their instincts of self-preservation were likely to be.

in 1984 called "Lady Grange on St Kilda". The Straw Chair is a two-act play by Sue Glover, also about the time on St Kilda, first performed in Edinburgh in 1988.

Boswell

and Johnson

discussed the subject during their 1773 tour of the Hebrides. Boswell wrote: "After dinner to-day, we talked of the extraordinary fact of Lady Grange’s being sent to St Kilda, and confined there for several years, without any means of relief. Dr Johnson said, if M’Leod would let it be known that he had such a place for naughty ladies, he might make it a very profitable island."

There are portraits of both James Erksine and Rachel Chiesley in the Scottish National Portrait Gallery

in Edinburgh, by William Aikman

and Sir John Baptiste de Medina

respectively. When the writer Margaret Macauley sought them out she discovered they had been placed together in the same cold store.

Scottish people

The Scottish people , or Scots, are a nation and ethnic group native to Scotland. Historically they emerged from an amalgamation of the Picts and Gaels, incorporating neighbouring Britons to the south as well as invading Germanic peoples such as the Anglo-Saxons and the Norse.In modern use,...

lawyer with Jacobite

Jacobitism

Jacobitism was the political movement in Britain dedicated to the restoration of the Stuart kings to the thrones of England, Scotland, later the Kingdom of Great Britain, and the Kingdom of Ireland...

sympathies. After 25 years of marriage and 9 children, the Granges had an acrimonious separation. After Lady Grange produced letters that she claimed were evidence of his treason

Treason

In law, treason is the crime that covers some of the more extreme acts against one's sovereign or nation. Historically, treason also covered the murder of specific social superiors, such as the murder of a husband by his wife. Treason against the king was known as high treason and treason against a...

able plottings against the Hanoverian

House of Hanover

The House of Hanover is a deposed German royal dynasty which has ruled the Duchy of Brunswick-Lüneburg , the Kingdom of Hanover, the Kingdom of Great Britain, the Kingdom of Ireland and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland...

government in London, her husband had her kidnapped in 1732. She was incarcerated in various remote locations on the western seaboard of Scotland, including the Monach Isles, Skye

Skye

Skye or the Isle of Skye is the largest and most northerly island in the Inner Hebrides of Scotland. The island's peninsulas radiate out from a mountainous centre dominated by the Cuillin hills...

and the distant islands of St Kilda

St Kilda, Scotland

St Kilda is an isolated archipelago west-northwest of North Uist in the North Atlantic Ocean. It contains the westernmost islands of the Outer Hebrides of Scotland. The largest island is Hirta, whose sea cliffs are the highest in the United Kingdom and three other islands , were also used for...

.

Lady Grange's father was convicted of murder and she is known to have had a violent temper; initially her absence seems to have caused little comment. News of her plight eventually reached her home town of Edinburgh

Edinburgh

Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland, the second largest city in Scotland, and the eighth most populous in the United Kingdom. The City of Edinburgh Council governs one of Scotland's 32 local government council areas. The council area includes urban Edinburgh and a rural area...

however, and an unsuccessful rescue attempt was effected by her lawyer, Thomas Hope of Rankeillor. She died in captivity, after being in effect imprisoned for 13 years. Her life has been remembered in poetry, prose and a play.

Early years

Rachel Chiesley was one of ten children born to John Chiesley of DalryDalry, Edinburgh

Dalry is an area close to the centre of the Scottish capital Edinburgh, between Haymarket and Gorgie. The phrase Gorgie-Dalry is commonly used by the council. It also borders Ardmillan. The area has become an increasingly desirable residential location in recent years, and the area is well located...

and Margaret Nicholson. The marriage was unhappy and Margaret took her husband to court for alimony

Alimony

Alimony is a U.S. term denoting a legal obligation to provide financial support to one's spouse from the other spouse after marital separation or from the ex-spouse upon divorce...

. She was awarded 1,700 merks by Sir George Lockhart of Carnwath

George Lockhart (advocate)

Sir George Lockhart of Carnwath was a Scottish lawyer.The son of Sir James Lockhart of Lee, laird of Lee, he was admitted as an advocate in 1656. He was knighted in 1663, and was appointed Dean of the Faculty of Advocates in 1672. He was celebrated for his persuasive eloquence...

, the Lord President of the Court of Session

Lord President of the Court of Session

The Lord President of the Court of Session is head of the judiciary in Scotland, and presiding judge of the College of Justice and Court of Session, as well as being Lord Justice General of Scotland and head of the High Court of Justiciary, the offices having been combined in 1836...

. Furious with the result, John Chiesley shot Lockhart dead on the Royal Mile

Royal Mile

The Royal Mile is a succession of streets which form the main thoroughfare of the Old Town of the city of Edinburgh in Scotland.As the name suggests, the Royal Mile is approximately one Scots mile long, and runs between two foci of history in Scotland, from Edinburgh Castle at the top of the Castle...

in Edinburgh

Edinburgh

Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland, the second largest city in Scotland, and the eighth most populous in the United Kingdom. The City of Edinburgh Council governs one of Scotland's 32 local government council areas. The council area includes urban Edinburgh and a rural area...

as he walked home from church on Easter Sunday, 31 March 1689. The assailant made no attempt to escape and confessed at his trial, held before the Lord Provost

Lord Provost

A Lord Provost is the figurative and ceremonial head of one of the principal cities of Scotland. Four cities, Aberdeen, Dundee, Edinburgh and Glasgow, have the right to appoint a Lord Provost instead of a provost...

the next day. Two days later he was taken from the Tolbooth

Heart of Midlothian (Royal Mile)

The Heart of Midlothian is a heart-shaped mosaic built into the pavement near the West Door of St Giles High Kirk on the Royal Mile in Edinburgh, not far from Parliament House, which was the former Parliament of Scotland, and now the site of the Court of Session and Signet Library.Together with...

to the Mercat Cross on the High Street. His right hand was cut off before he was hanged, and the pistol he had used for the murder was placed round his neck. Chiesley's birthday is unknown but she was baptised on 4 February 1679 and was probably born shortly before then, making her about ten years old at the time of her father's execution.

Marriage

Charles Erskine, 21st Earl of Mar

Charles Erskine, 21st Earl of Mar was a Scottish nobleman.On 2 April 1674 he married Mary Maule, daughter of George Maule, 2nd Earl of Panmure. Their son John Erskine became 22nd Earl of Mar....

and in 1689 his older brother John Erskine

John Erskine, 22nd Earl of Mar

John Erskine, 22nd and de jure 6th Earl of Mar, KT , Scottish Jacobite, was the eldest son of the 21st Earl of Mar , from whom he inherited estates that were heavily loaded with debt. By modern reckoning he was 22nd Earl of Mar of the first creation and de jure 6th Earl of Mar of the seventh...

, had already inherited the title of the 11th Earl of Mar

Earl of Mar

The Mormaer or Earl of Mar is a title that has been created seven times, all in the Peerage of Scotland. The first creation of the earldom was originally the provincial ruler of the province of Mar in north-eastern Scotland...

on their father's death. These were politically troubled times; the Jacobite cause was still popular in many parts of Scotland, and the younger Earl was nicknamed "Bobbing John" for his varied manoeuverings. After playing a prominent role in the Jacobite rebellion of 1715 he was stripped of his title, sent into exile

Exile

Exile means to be away from one's home , while either being explicitly refused permission to return and/or being threatened with imprisonment or death upon return...

, and never returned to Scotland.

The young Lady Grange has been described as a "wild beauty", and it is likely the marriage only took place after she became pregnant. This uncertain background notwithstanding, Lord and Lady Grange led a superficially uneventful domestic life. They divided their time between a town house at the foot of Niddry's Wynd off the High Street in Edinburgh and an estate at Preston

Preston, East Lothian

Preston is a village on the East Lothian coast of Scotland, to the south of Prestonpans, the east of Prestongrange, and the southwest of Cockenzie and Port Seton....

(near Prestonpans

Prestonpans

Prestonpans is a small town to the east of Edinburgh, Scotland, in the unitary council area of East Lothian. It has a population of 7,153 . It is the site of the 1745 Battle of Prestonpans, and has a history dating back to the 11th century...

in East Lothian

East Lothian

East Lothian is one of the 32 council areas of Scotland, and a lieutenancy Area. It borders the City of Edinburgh, Scottish Borders and Midlothian. Its administrative centre is Haddington, although its largest town is Musselburgh....

), where Lady Grange was the factor

Factor (agent)

A factor, from the Latin "he who does" , is a person who professionally acts as the representative of another individual or other legal entity, historically with his seat at a factory , notably in the following contexts:-Mercantile factor:In a relatively large company, there could be a hierarchy,...

(or supervisor) for a time. Her husband was a successful lawyer, becoming Lord Justice Clerk

Lord Justice Clerk

The Lord Justice Clerk is the second most senior judge in Scotland, after the Lord President of the Court of Session.The holder has the title in both the Court of Session and the High Court of Justiciary and is in charge of the Second Division of Judges in the Court of Session...

in 1710, and the marriage produced nine children:

- Charlie, born August 1709

- Johnnie, born March 1711, died age two months.

- James, born March 1713. He married his uncle "Bobbing" John's daughter Frances. Their son John eventually became Earl of Mar after the title was restored.

- Mary, born July 1714, who married John Keith the 3rd Earl of KintoreEarl of KintoreEarl of Kintore is a title in the Peerage of Scotland. It was created in 1677 for Sir John Keith, third son of William Keith, 6th Earl Marischal . He was made Lord Keith of Inverurie and Keith Hall at the same time, also in the Peerage of Scotland...

in August 1729. - Meggie, who died young in May 1717.

- Fannie, born December 1716.

- Jean, born in December 1717.

- Rachel

- John

In addition, Lady Grange miscarried

Miscarriage

Miscarriage or spontaneous abortion is the spontaneous end of a pregnancy at a stage where the embryo or fetus is incapable of surviving independently, generally defined in humans at prior to 20 weeks of gestation...

twice and one of the above children is known to have died in 1721.

However, there was an element of discord below the surface. In late 1717 or early 1718, Erskine received warnings from a friend that he had enemies in the government. At about the same time one of the children's tutors recorded in his diary that Lady Grange was "imperious with an unreasonable temper". Her outbursts were evidently also capable of frightening her younger daughters and it is a remarkable aspect of the story that no action was ever taken by any of Lady Grange's children on her behalf after her kidnapping, the eldest of whom would have been in their early twenties when she was abducted. This may become easier to understand with the knowledge that their mother had previously disinherited all of them, when the youngest were still infants.

Kidnap

As the Erksine marriage's trouble increased, Lady Grange's behaviour became increasingly unpredictable. In 1730, the factorship of the Preston estate was removed from her, further increasing her angst. Her discovery of an affair her husband was conducting with a Fanny Lindsay can only have made matters worse. In April of that year, she threatened suicide and to run naked through the streets of Edinburgh. She may have kept a razor under her pillow and attempted to intimidate her husband by reminding him whose daughter she was. On 27 July, she signed a formal letter of separation from James Erskine but things did not improve. For example, she barracked her husband in the street and in church and he and one of their children were forced to hide from her in a tavern for two hours or more on one occasion. She intercepted one of his letters and took it to the authorities alleging it was evidence of treason. She is also said to have stood outside the house in Niddry's Wynd, waving the letter and shouting obscenities on at least two occasions. In January 1732 she booked a stagecoachStagecoach

A stagecoach is a type of covered wagon for passengers and goods, strongly sprung and drawn by four horses, usually four-in-hand. Widely used before the introduction of railway transport, it made regular trips between stages or stations, which were places of rest provided for stagecoach travelers...

to London and James Erskine and his friends, afraid her presence there would cause them further trouble, decided it was time to take decisive action.

Scottish Highlands

The Highlands is an historic region of Scotland. The area is sometimes referred to as the "Scottish Highlands". It was culturally distinguishable from the Lowlands from the later Middle Ages into the modern period, when Lowland Scots replaced Scottish Gaelic throughout most of the Lowlands...

noblemen, Roderick MacLeod of Berneray

Berneray, North Uist

Berneray is an island and community in the Sound of Harris, Scotland. It is one of fifteen inhabited islands in the Outer Hebrides. It is famed for its rich and colourful history which has attracted much tourism....

and Macdonald of Morar

Morar

Morar is a small village on the west coast of Scotland, south of Mallaig. The name Morar is also applied to the wider district around the village....

and several of their men. After a bloody struggle, she was taken out of the city in a sedan chair

Litter (vehicle)

The litter is a class of wheelless vehicles, a type of human-powered transport, for the transport of persons. Examples of litter vehicles include lectica , jiao [较] , sedan chairs , palanquin , Woh , gama...

and then on horseback to Wester Polmaise near Falkirk

Falkirk

Falkirk is a town in the Central Lowlands of Scotland. It lies in the Forth Valley, almost midway between the two most populous cities of Scotland; north-west of Edinburgh and north-east of Glasgow....

, where she was held until 15 August on the ground floor of an uninhabited tower. She was by now over fifty years old.

From there she was taken west by Peter Fraser (a page of Lord Lovat

Simon Fraser, 11th Lord Lovat

Simon Fraser, 11th Lord Lovat , was a Scottish Jacobite and Chief of Clan Fraser, who was famous for his violent feuding and his changes of allegiance. In 1715, he had been a supporter of the House of Hanover, but in 1745 he changed sides and supported the Stuart claim on the crown of Scotland...

) and his men through Perthshire. At Balquhidder

Balquhidder

Balquhidder is a small village in the Stirling council area of Scotland. It is overlooked by the dramatic mountain terrain of the Braes of Balquhidder, at the head of Loch Voil. Balquhidder Glen is also popular for fishing, nature watching and walking...

, according to MacGregor tradition, she was entertained in the great hall, provided with a meal of venison, and slept on a heather bed covered with deerskins. The existence of St Fillan's

Fillan

Saint Fillan, Filan, Phillan, Fáelán or Faolan is the name of two Scottish saints, of Irish origin. The career of a historic individual lies behind at least one of these saints Saint Fillan, Filan, Phillan, Fáelán (Old Irish) or Faolan (modern Gaelic) is the name of (probably) two Scottish...

Pool on the River Fillan near Tyndrum

Tyndrum

Tyndrum is a small village in Scotland. Its Gaelic name translates as "the house on the ridge". It lies in Strathfillan, at the southern edge of Rannoch Moor.The village is notable mainly for being at an important crossroads of transport routes...

would have provided useful cover for her captors: it was regularly used as a cure for insanity, which would have helped to explain her presence to the curious. The details of the onward route from there are not clear but it is likely she was taken through Glen Coe

Glen Coe

Glen Coe is a glen in the Highlands of Scotland. It lies in the southern part of the Lochaber committee area of Highland Council, and was formerly part of the county of Argyll. It is often considered one of the most spectacular and beautiful places in Scotland, and is a part of the designated...

to Loch Ness

Loch Ness

Loch Ness is a large, deep, freshwater loch in the Scottish Highlands extending for approximately southwest of Inverness. Its surface is above sea level. Loch Ness is best known for the alleged sightings of the cryptozoological Loch Ness Monster, also known affectionately as "Nessie"...

and then through Glen Garry to Loch Hourn

Loch Hourn

Loch Hourn is a sea loch to the north of Knoydart, on the west coast of Scotland.-Geography:Loch Hourn runs inland from the Sound of Sleat, opposite the island of Skye, for 22 km to the head of the loch at Kinloch Hourn...

on the west coast. After a short delay she was then put on board ship to the Monach Isles. The difficulty of her position must have quickly become evident. She was in the company of men whose loyalty was to clan chieftains rather than the law, and few of them spoke any English at all. Their native Gaelic would have been incomprehensible to her, although as her years of captivity wore on she slowly learned something of the language. She complained that young members of the local aristocracy visited her as she waited by the shores of Loch Hourn, but that "they came with design to see me, but not to relieve me".

Monach Isles

The Monach Isles, also known as Heisker, lie 8 kilometres (5 mi) west of North UistNorth Uist

North Uist is an island and community in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland.-Geography:North Uist is the tenth largest Scottish island and the thirteenth largest island surrounding Great Britain. It has an area of , slightly smaller than South Uist. North Uist is connected by causeways to Benbecula...

in the Outer Hebrides

Outer Hebrides

The Outer Hebrides also known as the Western Isles and the Long Island, is an island chain off the west coast of Scotland. The islands are geographically contiguous with Comhairle nan Eilean Siar, one of the 32 unitary council areas of Scotland...

, an archipelago itself lying off the western coast of Scotland. The main islands are Ceann Ear

Ceann Ear

Disambiguation: "Ceann Ear" is a common Scottish placename meaning Eastern HeadlandCeann Ear is the largest island in the Monach or Heisgeir group off North Uist in north west Scotland. It is in size and connected by sandbanks to Ceann Iar via Sibhinis at low tide. It is said that it was at one...

, Ceann Iar

Ceann Iar

Disambiguation: "Ceann Iar" is a common Scottish placename meaning Western HeadlandCeann Iar is one of the Monach Isles/Heisgeir, to the west of North Uist in the Outer Hebrides. It is a slender island, approximately a mile, or two kilometres long.-Geography:Ceann Iar is the second largest of the...

and Shivinish, which are all linked at low tide and have a combined area of 357 hectares (882.2 acre). The islands are low-lying and fertile, and their population in the 18th century may have been about 100. At the time they were owned by Sir Alexander MacDonald of Sleat

Sleat

Sleat is a peninsula on the island of Skye in the Highland council area of Scotland, known as "the garden of Skye". It is the home of the clan MacDonald of Sleat...

, and Lady Grange was housed with his tacksman

Tacksman

A tacksman was a land-holder of intermediate legal and social status in Scottish Highland society.-Tenant and landlord:...

, another Alexander MacDonald, and his wife. When she complained about her condition, she was told by her host that he had no orders to provide her with either clothes, or food other than the normal fare he and his wife were used to. She lived in isolation for two years, not even being told the name of the island where she was living, and it took her some time to find out who her landlord was. She was there until June 1734, when John and Norman MacLeod from North Uist arrived to move her on. They told her they were taking her to Orkney, but instead set sail for the Atlantic outliers of St Kilda.

St Kilda

One of the more poignant ruins on the island of HirtaHirta

Hirta is the largest island in the St Kilda archipelago, on the western edge of Scotland. The name "Hiort" and "Hirta" have also been applied to the entire archipelago.-Geography:...

in the St Kilda archipelago is the site of Lady Grange's House. The "house" is in fact a large cleit or stone storage hut in the Village meadows which is said to resemble "a giant Christmas pudding". Some authorities believe it was rebuilt on the site of a larger black house

Black house

A blackhouse is a traditional type of house which used to be common in the Highlands of Scotland, the Hebrides, and Ireland.- Origin of the name :...

where she lived during her incarceration there, although in 1838 the grandson of a St Kildan who had assisted her quoted the dimensions as being "20 feet by 10 feet" (7 metres by 3 metres), which is roughly the size of the cleit.

Hirta is an order of magnitude more remote than the Monach Isles, lying 66 kilometres (41 mi) west-northwest of Benbecula

Benbecula

Benbecula is an island of the Outer Hebrides in the Atlantic Ocean off the west coast of Scotland. In the 2001 census it had a usually resident population of 1,249, with a sizable percentage of Roman Catholics. It forms part of the area administered by Comhairle nan Eilean Siar or the Western...

in the North Atlantic Ocean and the predominant theme of life on St Kilda was isolation. When Martin Martin

Martin Martin

Martin Martin was a Scottish writer best known for his work A Description of the Western Isles of Scotland . This book is particularly noted for its information on the St Kilda archipelago...

visited the islands in 1697, the only means of making the journey was by open longboat, which could take several days and nights of rowing and sailing across the open ocean and was next to impossible in autumn and winter. In all seasons, waves up to 12 metres (40 ft) high lash the beach of Village Bay, and even on calmer days landing on the slippery rocks can be hazardous. Cut off by distance and weather, the natives knew little of the rest of the world.

Lady Grange's circumstances were correspondingly more uncomfortable. She described Hirta as "a viled neasty, stinking poor Isle" and insisted that "I was in great miserie in the Husker but I'm ten times worse and worse here". Her lodgings were very primitive. They had an earthen floor, rain ran down the walls and in winter snow had to be scooped out in handfuls from behind the bed. She spent her days asleep, drank as much whisky as was available to her, and wandered the shore at night bemoaning her fate. During her sojourn on Hirta she wrote two letters relating her story, which eventually reached Edinburgh. One, dated 20 January 1738, found its way to Thomas Hope of Rankeillor, her lawyer, in December 1740. The letter caused a sensation in Edinburgh but James Erskine's friends managed to block attempts by Hope to obtain a warrant to search St Kilda.

Inveresk

Inveresk is a civil parish and was formerly a village that now forms the southern part of Musselburgh. It is situated on slightly elevated ground at the south of Musselburgh in East Lothian, Scotland...

, Lady Grange writes bitterly of the roles of Lord Lovat and Roderick McLeod in her capture and bemoans being described by Sir Alexander MacDonald as "the cargo". Hope had known of Lady Grange's removal from Edinburgh but had assumed she would be well cared for. Appalled by her condition, he paid for a sloop

Sloop

A sloop is a sail boat with a fore-and-aft rig and a single mast farther forward than the mast of a cutter....

with twenty armed men on board to go to St Kilda at his own expense. It had already set sail by 14 February 1741, but it arrived too late. Lady Grange had been removed from the island, probably in the summer of 1740.

After the Battle of Culloden

Battle of Culloden

The Battle of Culloden was the final confrontation of the 1745 Jacobite Rising. Taking place on 16 April 1746, the battle pitted the Jacobite forces of Charles Edward Stuart against an army commanded by William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland, loyal to the British government...

in 1746, it was rumoured that Prince Charles Edward Stuart and some of his senior Jacobite

Jacobitism

Jacobitism was the political movement in Britain dedicated to the restoration of the Stuart kings to the thrones of England, Scotland, later the Kingdom of Great Britain, and the Kingdom of Ireland...

aides had escaped to St Kilda. An expedition was launched, and in due course British soldiers were ferried ashore to Hirta. They found a deserted village, as the St Kildans, fearing pirates, had fled to caves to the west. When they were persuaded to come down, the soldiers discovered that the isolated natives knew nothing of the Prince and had never heard of King George II

George II of Great Britain

George II was King of Great Britain and Ireland, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg and Archtreasurer and Prince-elector of the Holy Roman Empire from 11 June 1727 until his death.George was the last British monarch born outside Great Britain. He was born and brought up in Northern Germany...

either. Paradoxically, Lady Grange's letters and her resultant evacuation from the island, may have prevented her being found by this expedition.

Skye

By 1740 Lady Grange was 61 years old. Removed from St Kilda in haste, she was transported to various locations in the GàidhealtachdGàidhealtachd

The Gàidhealtachd , sometimes known as A' Ghàidhealtachd , usually refers to the Scottish highlands and islands, and especially the Scottish Gaelic culture of the area. The corresponding Irish word Gaeltacht however refers strictly to an Irish speaking area...

including possibly Assynt

Assynt

Assynt is a civil parish in west Sutherland, Highland, Scotland – north of Ullapool.It is famous for its landscape and its remarkable mountains...

in the far north west of mainland Scotland and the Outer Hebridean locations of Harris and Uist

Uist

Uist or The Uists are the central group of islands in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland.North Uist and South Uist are linked by causeways running via Benbecula and Grimsay, and the entire group is sometimes known as the Uists....

before arriving at Waternish

Waternish

Waternish or Bhatairnis/Vaternish is a peninsula approximately long on the island of Skye, Scotland, situated between Loch Dunvegan and Loch Snizort in the northwest of the island, and traditionally inhabited and owned by Clan MacLeod whose clan seat is at the nearby Dunvegan Castle. The current...

on Skye in 1742. Local folklore suggests she may have been kept for 18 months in a cave either at Idrigill

Uig, Skye

The village of Uig lies at the head of the sheltered inlet of Uig Bay on the west coast of the Trotternish peninsula on the Isle of Skye, Scotland. Uig is situated partly on the raised beach around the head of the bay and partly on the steep slopes behind it...

on the Trotternish

Trotternish

Trotternish or Tròndairnis is the northernmost peninsula of the Isle of Skye, in Scotland.One of its more well-known features is the Trotternish landslip, a massive landslide that runs almost the full length of the peninsula, some...

peninsula or on the Duirinish

Duirinish, Skye

Duirinish is a peninsula on the island of Skye in Scotland. It is situated in the north west between Loch Dunvegan and Loch Bracadale.Skye's shape defies description and W. H. Murray wrote that "Skye is sixty miles long, but what might be its breadth is beyond the ingenuity of man to state"...

coast near the stacks

Stack (geology)

A stack is a geological landform consisting of a steep and often vertical column or columns of rock in the sea near a coast, isolated by erosion. Stacks are formed through processes of coastal geomorphology, which are entirely natural. Time, wind and water are the only factors involved in the...

known as a "Macleod's Maidens". She was certainly later housed with Rory MacNeil at Trumpan

Trumpan

Trumpan is a hamlet located on the Vaternish peninsula in the Isle of Skye, in the Scottish council area of the Highland. Trumpan church, which is now a ruin, was the focus of a particularly brutal incident in 1578, when the Clan MacDonald of Uist travelled to Trumpan in eight boats and under...

in Waternish. She died there on 12 May 1745, and MacNeil had her "decently interred" the following week in the local churchyard. For reasons unknown a second funeral was held at nearby Duirinish some time thereafter, where a large crowd gathered to watch the burial of a coffin filled with turf and stones.

It is sometimes stated that this was her third funeral, Lord Grange having conducted one in Edinburgh shortly after her kidnapping. However, this story first appears in writing in 1845 and no other evidence of its existence has emerged.

Motivations

By any standards, Lady Grange's story is a remarkable one and several key questions require explanation. Firstly, what drove James Erskine to these extraordinary lengths? Secondly, why were so many individuals willing to participate in this illegal and dangerous kidnapping of his wife, and thirdly how was she held for so long without rescue?The first and second questions are related. Erskine's brother had already been exiled for his support of the Jacobites. Simon Fraser, Lord Lovat, a key figure in Lady Grange's abduction was himself executed for his part in the Jacobite Rising of 1745

Jacobite Rising of 1745

The Jacobite rising of 1745, often referred to as "The 'Forty-Five," was the attempt by Charles Edward Stuart to regain the British throne for the exiled House of Stuart. The rising occurred during the War of the Austrian Succession when most of the British Army was on the European continent...

. No concrete evidence of Erskine's plotting against the crown or government has ever emerged, but any threat of such exposure, whether based in fact or fantasy would certainly have been taken very seriously by all concerned. It was thus relatively easy for Erskine to find accomplices amongst the Highland gentry. In addition to Simon Fraser and Alexander Macdonald of Sleat

Clan MacDonald of Sleat

Clan Macdonald of Sleat, sometimes known as Clan Donald North and in Gaelic Clann Ùisdein , is a Scottish clan and a branch of Clan Donald — one of the largest Scottish clans. The founder of the Macdonalds of Sleat is Ùisdean, 6th great-grandson of Somhairle, a 12th century Rì Innse Gall...

, the Sobieski Stuarts (two English brothers who claimed descent from Prince Charles Edward Stuart) listed Norman MacLeod of Dunvegan

Norman MacLeod (The Wicked Man)

Norman MacLeod , also known in his own time and within clan tradition as The Wicked Man , was an 18th century politician, and a clan chief of Clan MacLeod. In the 20th century, one chief of Clan MacLeod attempted to have his nickname changed from The Wicked Man, to The Red Man...

—who became known as "The Wicked Man"—as the senior accomplices.

Erskine himself was a "singular compound of good and bad qualities". In addition to his legal career he was elected to Parliament in 1734 and he survived the vicissitudes of the Jacobite rebellions unscathed. It is also clear that he was a philanderer and over-partial to claret

Claret

Claret is a name primarily used in British English for red wine from the Bordeaux region of France.-Usage:Claret derives from the French clairet, a now uncommon dark rosé and the most common wine exported from Bordeaux until the 18th century...

, whilst at the same time deeply religious. This last quality would have been instrumental in any decision not to have his wife assassinated, and he did not marry his long-term partner Fanny Lindsay until after he had heard of the first Lady Grange's death.

The third question is perhaps the easiest to answer. The Hebrides

Hebrides

The Hebrides comprise a widespread and diverse archipelago off the west coast of Scotland. There are two main groups: the Inner and Outer Hebrides. These islands have a long history of occupation dating back to the Mesolithic and the culture of the residents has been affected by the successive...

were very remote from the anglophone

English-speaking world

The English-speaking world consists of those countries or regions that use the English language to one degree or another. For more information, please see:Lists:* List of countries by English-speaking population...

world in the early 18th century and no reliable naval charts of the area became available until 1776. Without local assistance and knowledge, finding a captive in this wilderness would have required a significant expeditionary force. Nonetheless, the lack of action taken by Edinburgh society in general and her children in particular to retrieve one of their own is remarkable. The Kirk

Church of Scotland

The Church of Scotland, known informally by its Scots language name, the Kirk, is a Presbyterian church, decisively shaped by the Scottish Reformation....

hierarchy, for example, made no attempt to contact her or convey news of her condition to the capital, yet they could easily have done so. Whatever the call of morality and natural justice may have suggested, it is clear that John Chiesley's daughter did not command a sympathetic audience in her home town.

There is also little doubt that 18th-century attitudes to women in general were a significant factor. Divorces were complex and divorced mothers were rarely given custody of children. Something of James Erskine's attitude to these matters may perhaps be gleaned from the fact that for his first speech in the House of Commons

House of Commons of Great Britain

The House of Commons of Great Britain was the lower house of the Parliament of Great Britain between 1707 and 1801. In 1707, as a result of the Acts of Union of that year, it replaced the House of Commons of England and the third estate of the Parliament of Scotland, as one of the most significant...

he chose to oppose the repeal of various laws relating to witchcraft

Witchcraft

Witchcraft, in historical, anthropological, religious, and mythological contexts, is the alleged use of supernatural or magical powers. A witch is a practitioner of witchcraft...

. Even in his day this appeared unduly conservative and his perorations were met with laughter, which effectively ended his political career before it had begun. Writing in the mid-19th century the Sobieski Stuarts told the tale from the perspective of the descendants of the Highland aristocrats who had been responsible for Chiesley's kidnap and imprisonment. They emphasise Lady Grange's personal shortcomings, although to modern sensibilities these hardly seem good reasons for a judge and Member of Parliament

Member of Parliament

A Member of Parliament is a representative of the voters to a :parliament. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, the term applies specifically to members of the lower house, as upper houses often have a different title, such as senate, and thus also have different titles for its members,...

and his wealthy friends to organise an illegal kidnapping and life sentence.

As for Lady Grange herself, her vituperative outbursts and indulgence in alcohol were clearly important factors in her undoing. Alexander Carlyle

Alexander Carlyle

Very Rev Alexander Carlyle was a Scottish church leader, and autobiographer.He was born in Cummertrees, Dumfriesshire, the son of the local minister and brought up in Prestonpans, East Lothian. He was a witness to the Battle of Prestonpans in 1745 where he was part of the government Edinburgh...

described her as "stormy and outrageous", whilst noting that it was in her husband's interests to exaggerate the nature of her violent emotions. Macauley (2009) takes the view that the ultimate cause of her troubles was her reaction to her husband's infidelity. In an attempt to end his relationship with Mrs Lindsay, (who owned a coffee house in Haymarket, Edinburgh

Haymarket, Edinburgh

Haymarket is an area of Edinburgh, Scotland. It is in the west of the city and is a focal point for many main roads, notably Dalry Road , Corstorphine Road and Shandwick Place .Haymarket contains a number of popular pubs, cafés and...

), Rachel threatened to expose him as a Jacobite sympathiser. Perhaps she did not understand the magnitude of this accusation and the danger it posed to her husband and his friends, or how ruthless their instincts of self-preservation were likely to be.

In literature and the arts

Rachel Chiesley's tale inspired a romantic poem called "Epistle from Lady Grange to Edward D— Esq" written by William Erskine in 1798 and a 1905 novel entitled The Lady of Hirta, a Tale of the Isles by W. C. Mackenzie. Edwin Morgan also published a sonnetSonnet

A sonnet is one of several forms of poetry that originate in Europe, mainly Provence and Italy. A sonnet commonly has 14 lines. The term "sonnet" derives from the Occitan word sonet and the Italian word sonetto, both meaning "little song" or "little sound"...

in 1984 called "Lady Grange on St Kilda". The Straw Chair is a two-act play by Sue Glover, also about the time on St Kilda, first performed in Edinburgh in 1988.

Boswell

James Boswell

James Boswell, 9th Laird of Auchinleck was a lawyer, diarist, and author born in Edinburgh, Scotland; he is best known for the biography he wrote of one of his contemporaries, the English literary figure Samuel Johnson....

and Johnson

Samuel Johnson

Samuel Johnson , often referred to as Dr. Johnson, was an English author who made lasting contributions to English literature as a poet, essayist, moralist, literary critic, biographer, editor and lexicographer...

discussed the subject during their 1773 tour of the Hebrides. Boswell wrote: "After dinner to-day, we talked of the extraordinary fact of Lady Grange’s being sent to St Kilda, and confined there for several years, without any means of relief. Dr Johnson said, if M’Leod would let it be known that he had such a place for naughty ladies, he might make it a very profitable island."

There are portraits of both James Erksine and Rachel Chiesley in the Scottish National Portrait Gallery

Scottish National Portrait Gallery

The Scottish National Portrait Gallery is an art gallery on Queen Street, Edinburgh, Scotland. It holds the national collections of portraits, all of which are of, but not necessarily by, Scots. In addition it also holds the Scottish National Photography Collection...

in Edinburgh, by William Aikman

William Aikman (painter)

William Aikman was a Scottish portrait-painter.-Life and career:Aikman was the son of William Aikman, of Cairney. His father intended that he should follow the law, and gave him an education suitable to these views; but the strong predilection of the son to the fine arts induced him to attach...

and Sir John Baptiste de Medina

John Baptist Medina

Sir John Baptist Medina or John Baptiste de Medina was an artist of Flemish-Spanish origin who worked in England and Scotland, mostly as a portrait painter, though he was also the first illustrator of Paradise Lost by John Milton in 1688.-Life and portrait-painting:Medina was the son of a Spanish...

respectively. When the writer Margaret Macauley sought them out she discovered they had been placed together in the same cold store.

See also

- Tibbie TamsonTibbie TamsonTibbie Tamson was a Scottish woman, who lived in Selkirk, in the Scottish Borders, in the 18th century. Her grave is located on a hillside, around 1.5 miles north of Selkirk, at . While Tamson certainly did exist, and is recorded as dying in 1790, few facts are known about her. Historic Scotland...

, an 18th-century Scots woman, whose persecution may have led to her suicide. - Iris RobinsonIris RobinsonIris Robinson is a former Northern Ireland Unionist politician. She is married to Peter Robinson, who is currently the First Minister in the Northern Ireland Assembly....

, a 21st-century politician from Northern Ireland, who became caught up in a scandal that has resulted in her receiving psychiatric treatment. - Lisbeth SalanderLisbeth SalanderLisbeth Salander is a fictional character created by Swedish author and journalist Stieg Larsson. She is the heroine of Larsson's award-winning "Millennium series", first appearing in the novel The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo...

, a 21st-century fictional heroine who is declared mentally incompetent by authority figures trying to control her behaviour.

External links

- Lady Grange in Edinburgh 1730 (pdf) contains a copy of the signed letter of separation written in 1730.

- Lady Grange, detailed by herself in a letter from St. Kilda

- Canmore photograph of Lady Grange's "house" on St Kilda