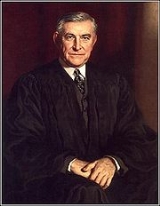

Owen Josephus Roberts

Encyclopedia

Owen Josephus Roberts was an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court for fifteen years. He also led the fact-finding commission that investigated the attack on Pearl Harbor

. At the time of World War II

, he was the only Republican

appointed Judge on the Supreme Court of the United States

and one of only three to vote against Franklin D. Roosevelt

's orders for Japanese American internment

camps in Korematsu v. United States

.

and the University of Pennsylvania

, where he was elected to the Phi Beta Kappa Society and was the editor of The Daily Pennsylvanian

. He completed his bachelor's degree in 1895 and went on to graduate at the top of his class from University of Pennsylvania Law School

in 1898.

He first gained notice as an assistant district attorney in Philadelphia. He was appointed by President Calvin Coolidge

to investigate oil reserve scandals, known as the Teapot Dome scandal

. This led to the prosecution and conviction of Albert B. Fall

, the former Secretary of the Interior

, for bribe-taking.

after Hoover's nomination of John J. Parker

was defeated by the Senate.

On the Court, Roberts was a swing vote between those, led by Justices Louis Brandeis

, Benjamin Cardozo, and Harlan Fiske Stone

, as well as Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes

, who would allow a broader interpretation of the Commerce Clause

to allow Congress to pass New Deal

legislation that would provide for a more active federal role in the national economy, and the Four Horsemen

(Justices James Clark McReynolds

, Pierce Butler

, George Sutherland

, and Willis Van Devanter

) who favored a narrower interpretation of the Commerce Clause and believed that the Fourteenth Amendment

Due Process Clause protected a strong "liberty of contract

."

In 1936's United States v. Butler

, Roberts sided with the Four Horsemen and wrote an opinion striking down the Agricultural Adjustment Act

as beyond Congress's Commerce powers.

," although Roberts's vote in Parrish occurred several months before announcement of the Court-packing plan. While Roberts is often accused of inconsistency in his jurisprudential stance towards the New Deal, legal scholars note that he had previously argued for a broad interpretation of government power in the 1934 case of Nebbia v. New York

, and so his later vote in Parrish was not a complete reversal.

Roberts wrote the majority opinion in the landmark case of New Negro Alliance v. Sanitary Grocery Co.

, , which safeguarded the right to boycott

in the context of the struggle by African Americans against discriminatory hiring practices. He also wrote the majority opinion sustaining provisions of the second Agricultural Adjustment Act applied to the marketing of tobacco in Mulford v. Smith, .

Roberts was appointed by Roosevelt to head the commission

investigating the attack on Pearl Harbor

; his report was published in 1942 and was highly critical of the United States Military. Journalist John T. Flynn

wrote at the time that Roosevelt's appointment of Roberts:

Perhaps influenced by his work on the Pearl Harbor commission, Roberts dissented from the Court's decision upholding internment of Japanese-Americans along the West Coast

in 1944's Korematsu v. United States

.

In his later years on the bench, Roberts was the only Justice on the Supreme Court not appointed (or in the case of Stone, who had become Chief Justice, promoted) by President Franklin D. Roosevelt

. Roberts became frustrated with the willingness of the new justices to overturn precedent and with what he saw as their result-oriented liberalism as judges. Roberts dissented bitterly in the 1944 case of Smith v. Allwright

, which in finding the white primary unconstitutional overruled an opinion Roberts himself had written nine years previously. It was in his dissent in that case that he coined the oft-quoted phrase that the frequent overruling of decisions "tends to bring adjudications of this tribunal into the same class as a restricted railroad ticket, good for this day and train only."

Roberts retired from the Court the following year, in 1945; Roberts's relations with his colleagues had become so strained that fellow Justice Hugo Black

refused to sign the customary letter acknowledging Roberts's service on his retirement. Other justices refused to sign a modified letter that would have been acceptable to Black, and in the end, no letter was ever sent.

Shortly after leaving the Court, Roberts reportedly burned all of his legal and judicial papers. As a result, there is no significant collection of Roberts' manuscript papers, as there is for most other modern Justices. Roberts did prepare a short memorandum discussing his alleged change of stance around the time of the court-packing effort, which he left in the hands of Justice Felix Frankfurter

.

, convened the Dublin Declaration, a plan to change the U.N. General Assembly into a world legislature with "limited but definite and adequate power for the prevention of war."

Roberts served as the Dean of the University of Pennsylvania Law School from 1948 to 1951.

He died at his Chester County (Pennsylvania) farm after a four-month illness. He was survived by his wife, Elizabeth Caldwell Rogers, and daughter, Elizabeth Hamilton.

Germantown Academy

named its debate society after Owen J. Roberts in his honor. In addition, a school district near Pottstown, Pennsylvania

, the Owen J. Roberts School District, adopted his name.

In 1946 he was the first lay person elected to serve as President of the House of Deputies for the General Convention of the Episcopal Church. He served for one convention.

Attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike conducted by the Imperial Japanese Navy against the United States naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on the morning of December 7, 1941...

. At the time of World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

, he was the only Republican

Republican Party (United States)

The Republican Party is one of the two major contemporary political parties in the United States, along with the Democratic Party. Founded by anti-slavery expansion activists in 1854, it is often called the GOP . The party's platform generally reflects American conservatism in the U.S...

appointed Judge on the Supreme Court of the United States

Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States is the highest court in the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all state and federal courts, and original jurisdiction over a small range of cases...

and one of only three to vote against Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt , also known by his initials, FDR, was the 32nd President of the United States and a central figure in world events during the mid-20th century, leading the United States during a time of worldwide economic crisis and world war...

's orders for Japanese American internment

Japanese American internment

Japanese-American internment was the relocation and internment by the United States government in 1942 of approximately 110,000 Japanese Americans and Japanese who lived along the Pacific coast of the United States to camps called "War Relocation Camps," in the wake of Imperial Japan's attack on...

camps in Korematsu v. United States

Korematsu v. United States

Korematsu v. United States, 323 U.S. 214 , was a landmark United States Supreme Court case concerning the constitutionality of Executive Order 9066, which ordered Japanese Americans into internment camps during World War II....

.

Early life and career

Roberts was born in Philadelphia and attended Germantown AcademyGermantown Academy

Germantown Academy is America's oldest nonsectarian day school, founded on December 6, 1759 . Germantown Academy is now a K-12 school in the Philadelphia suburb of Fort Washington, having moved from its original Germantown campus in 1965...

and the University of Pennsylvania

University of Pennsylvania

The University of Pennsylvania is a private, Ivy League university located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States. Penn is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States,Penn is the fourth-oldest using the founding dates claimed by each institution...

, where he was elected to the Phi Beta Kappa Society and was the editor of The Daily Pennsylvanian

The Daily Pennsylvanian

The Daily Pennsylvanian is the independent daily student newspaper of the University of Pennsylvania.It is published every weekday when the university is in session by a staff of more than 250 students. During the summer months, a smaller staff produces a weekly version called The Summer...

. He completed his bachelor's degree in 1895 and went on to graduate at the top of his class from University of Pennsylvania Law School

University of Pennsylvania Law School

The University of Pennsylvania Law School, located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, is the law school of the University of Pennsylvania. A member of the Ivy League, it is among the oldest and most selective law schools in the nation. It is currently ranked 7th overall by U.S. News & World Report,...

in 1898.

He first gained notice as an assistant district attorney in Philadelphia. He was appointed by President Calvin Coolidge

Calvin Coolidge

John Calvin Coolidge, Jr. was the 30th President of the United States . A Republican lawyer from Vermont, Coolidge worked his way up the ladder of Massachusetts state politics, eventually becoming governor of that state...

to investigate oil reserve scandals, known as the Teapot Dome scandal

Teapot Dome scandal

The Teapot Dome Scandal was a bribery incident that took place in the United States in 1922–23, during the administration of President Warren G. Harding. Secretary of the Interior Albert B. Fall leased Navy petroleum reserves at Teapot Dome and two other locations to private oil companies at low...

. This led to the prosecution and conviction of Albert B. Fall

Albert B. Fall

Albert Bacon Fall was a United States Senator from New Mexico and the Secretary of the Interior under President Warren G. Harding, infamous for his involvement in the Teapot Dome scandal.-Early life and family:...

, the former Secretary of the Interior

United States Secretary of the Interior

The United States Secretary of the Interior is the head of the United States Department of the Interior.The US Department of the Interior should not be confused with the concept of Ministries of the Interior as used in other countries...

, for bribe-taking.

Supreme Court

Roberts was appointed to the Supreme Court by Herbert HooverHerbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover was the 31st President of the United States . Hoover was originally a professional mining engineer and author. As the United States Secretary of Commerce in the 1920s under Presidents Warren Harding and Calvin Coolidge, he promoted partnerships between government and business...

after Hoover's nomination of John J. Parker

John J. Parker

John Johnston Parker was a U.S. judge who failed confirmation to the Supreme Court by one vote. He was also the U.S. alternate judge at the Nuremberg Trials of Nazi war criminals and later served on the United Nations' International Law Commission.John J. Parker was born in Monroe, North Carolina,...

was defeated by the Senate.

On the Court, Roberts was a swing vote between those, led by Justices Louis Brandeis

Louis Brandeis

Louis Dembitz Brandeis ; November 13, 1856 – October 5, 1941) was an Associate Justice on the Supreme Court of the United States from 1916 to 1939.He was born in Louisville, Kentucky, to Jewish immigrant parents who raised him in a secular mode...

, Benjamin Cardozo, and Harlan Fiske Stone

Harlan Fiske Stone

Harlan Fiske Stone was an American lawyer and jurist. A native of New Hampshire, he served as the dean of Columbia Law School, his alma mater, in the early 20th century. As a member of the Republican Party, he was appointed as the 52nd Attorney General of the United States before becoming an...

, as well as Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes

Charles Evans Hughes

Charles Evans Hughes, Sr. was an American statesman, lawyer and Republican politician from New York. He served as the 36th Governor of New York , Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States , United States Secretary of State , a judge on the Court of International Justice , and...

, who would allow a broader interpretation of the Commerce Clause

Commerce Clause

The Commerce Clause is an enumerated power listed in the United States Constitution . The clause states that the United States Congress shall have power "To regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian Tribes." Courts and commentators have tended to...

to allow Congress to pass New Deal

New Deal

The New Deal was a series of economic programs implemented in the United States between 1933 and 1936. They were passed by the U.S. Congress during the first term of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The programs were Roosevelt's responses to the Great Depression, and focused on what historians call...

legislation that would provide for a more active federal role in the national economy, and the Four Horsemen

Four Horsemen (Supreme Court)

The "Four Horsemen" was the nickname given by the press to four conservative members of the United States Supreme Court during the 1932–1937 terms, who opposed the New Deal agenda of President Franklin Roosevelt. They were Justices Pierce Butler, James Clark McReynolds, George Sutherland,...

(Justices James Clark McReynolds

James Clark McReynolds

James Clark McReynolds was an American lawyer and judge who served as United States Attorney General under President Woodrow Wilson and as an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court...

, Pierce Butler

Pierce Butler (justice)

Pierce Butler was an American jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1923 until his death in 1939...

, George Sutherland

George Sutherland

Alexander George Sutherland was an English-born U.S. jurist and political figure. One of four appointments to the Supreme Court by President Warren G. Harding, he served as an Associate Justice of the U.S...

, and Willis Van Devanter

Willis Van Devanter

Willis Van Devanter was an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court, January 3, 1911 to June 2, 1937.- Early life and career :...

) who favored a narrower interpretation of the Commerce Clause and believed that the Fourteenth Amendment

Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution was adopted on July 9, 1868, as one of the Reconstruction Amendments.Its Citizenship Clause provides a broad definition of citizenship that overruled the Dred Scott v...

Due Process Clause protected a strong "liberty of contract

Contract

A contract is an agreement entered into by two parties or more with the intention of creating a legal obligation, which may have elements in writing. Contracts can be made orally. The remedy for breach of contract can be "damages" or compensation of money. In equity, the remedy can be specific...

."

In 1936's United States v. Butler

United States v. Butler

United States v. Butler, , was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States ruled that the processing taxes instituted under the 1933 Agricultural Adjustment Act were unconstitutional...

, Roberts sided with the Four Horsemen and wrote an opinion striking down the Agricultural Adjustment Act

Agricultural Adjustment Act

The Agricultural Adjustment Act was a United States federal law of the New Deal era which restricted agricultural production by paying farmers subsidies not to plant part of their land and to kill off excess livestock...

as beyond Congress's Commerce powers.

"Switch in Time that Saved the Nine"

Roberts switched his position on the constitutionality of the New Deal in late 1936, and the Supreme Court handed down West Coast Hotel v. Parrish in 1937, upholding the constitutionality of minimum wage laws. Subsequently, the Court would vote to uphold all New Deal programs. Since President Roosevelt's plan to appoint several new justices as part of his "Court-packing" plan of 1937 coincided with the Court's favorable decision in Parrish, many people called Roberts's vote in that case the "switch in time that saved nineThe switch in time that saved nine

“The switch in time that saved nine” is the name given to what was perceived as the sudden jurisprudential shift by Associate Justice Owen J. Roberts of the U.S. Supreme Court in West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish...

," although Roberts's vote in Parrish occurred several months before announcement of the Court-packing plan. While Roberts is often accused of inconsistency in his jurisprudential stance towards the New Deal, legal scholars note that he had previously argued for a broad interpretation of government power in the 1934 case of Nebbia v. New York

Nebbia v. New York

Nebbia v. New York, 291 U.S. 502 , was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States determined whether the state of New York could regulate the price of milk for dairy farmers, dealers, and retailers....

, and so his later vote in Parrish was not a complete reversal.

Roberts wrote the majority opinion in the landmark case of New Negro Alliance v. Sanitary Grocery Co.

New Negro Alliance v. Sanitary Grocery Co.

New Negro Alliance v. Sanitary Grocery Co., 303 U.S. 552 , was a landmark United States Supreme Court decision in the jurisprudence of the United States, safeguarding a right to boycott and in the struggle by African Americans against discriminatory hiring practices.-External links:**...

, , which safeguarded the right to boycott

Boycott

A boycott is an act of voluntarily abstaining from using, buying, or dealing with a person, organization, or country as an expression of protest, usually for political reasons...

in the context of the struggle by African Americans against discriminatory hiring practices. He also wrote the majority opinion sustaining provisions of the second Agricultural Adjustment Act applied to the marketing of tobacco in Mulford v. Smith, .

Roberts was appointed by Roosevelt to head the commission

Roberts Commission

Two presidentially-appointed commissions have been described as "the Roberts Commission." One related to the circumstances of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, and another related to the protection of cultural resources during and following World War II...

investigating the attack on Pearl Harbor

Attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike conducted by the Imperial Japanese Navy against the United States naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on the morning of December 7, 1941...

; his report was published in 1942 and was highly critical of the United States Military. Journalist John T. Flynn

John T. Flynn

John Thomas Flynn was an American journalist best known for his opposition to President Franklin D. Roosevelt and to American entry into World War II.-Career:...

wrote at the time that Roosevelt's appointment of Roberts:

was a master stroke. What the public overlooked was that Roberts had been one of the most clamorous among those screaming for an open declaration of war. He had doffed his robes, taken to the platform in his frantic apprehensions and demanded that we immediately unite with Great Britain in a single nation. The Pearl Harbor incident had given him what he had been yelling for – America's entrance into the war. On the war issue he was one of the President's most impressive allies. Now he had his wish. He could be depended on not to cast any stain upon it in its infancy.

Perhaps influenced by his work on the Pearl Harbor commission, Roberts dissented from the Court's decision upholding internment of Japanese-Americans along the West Coast

West Coast of the United States

West Coast or Pacific Coast are terms for the westernmost coastal states of the United States. The term most often refers to the states of California, Oregon, and Washington. Although not part of the contiguous United States, Alaska and Hawaii do border the Pacific Ocean but can't be included in...

in 1944's Korematsu v. United States

Korematsu v. United States

Korematsu v. United States, 323 U.S. 214 , was a landmark United States Supreme Court case concerning the constitutionality of Executive Order 9066, which ordered Japanese Americans into internment camps during World War II....

.

In his later years on the bench, Roberts was the only Justice on the Supreme Court not appointed (or in the case of Stone, who had become Chief Justice, promoted) by President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt , also known by his initials, FDR, was the 32nd President of the United States and a central figure in world events during the mid-20th century, leading the United States during a time of worldwide economic crisis and world war...

. Roberts became frustrated with the willingness of the new justices to overturn precedent and with what he saw as their result-oriented liberalism as judges. Roberts dissented bitterly in the 1944 case of Smith v. Allwright

Smith v. Allwright

Smith v. Allwright , 321 U.S. 649 , was a very important decision of the United States Supreme Court with regard to voting rights and, by extension, racial desegregation. It overturned the Democratic Party's use of all-white primaries in Texas, and other states where the party used the...

, which in finding the white primary unconstitutional overruled an opinion Roberts himself had written nine years previously. It was in his dissent in that case that he coined the oft-quoted phrase that the frequent overruling of decisions "tends to bring adjudications of this tribunal into the same class as a restricted railroad ticket, good for this day and train only."

Roberts retired from the Court the following year, in 1945; Roberts's relations with his colleagues had become so strained that fellow Justice Hugo Black

Hugo Black

Hugo Lafayette Black was an American politician and jurist. A member of the Democratic Party, Black represented Alabama in the United States Senate from 1927 to 1937, and served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1937 to 1971. Black was nominated to the Supreme...

refused to sign the customary letter acknowledging Roberts's service on his retirement. Other justices refused to sign a modified letter that would have been acceptable to Black, and in the end, no letter was ever sent.

Shortly after leaving the Court, Roberts reportedly burned all of his legal and judicial papers. As a result, there is no significant collection of Roberts' manuscript papers, as there is for most other modern Justices. Roberts did prepare a short memorandum discussing his alleged change of stance around the time of the court-packing effort, which he left in the hands of Justice Felix Frankfurter

Felix Frankfurter

Felix Frankfurter was an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court.-Early life:Frankfurter was born into a Jewish family on November 15, 1882, in Vienna, Austria, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in Europe. He was the third of six children of Leopold and Emma Frankfurter...

.

Later life

While in retirement Roberts, along with Robert P. BassRobert P. Bass

Robert Perkins Bass was an American farmer, forestry expert, and Republican politician from Peterborough, New Hampshire. He served in both houses of the New Hampshire Legislature and as chairman of the state's Forestry Commission before being elected governor of New Hampshire in 1910...

, convened the Dublin Declaration, a plan to change the U.N. General Assembly into a world legislature with "limited but definite and adequate power for the prevention of war."

Roberts served as the Dean of the University of Pennsylvania Law School from 1948 to 1951.

He died at his Chester County (Pennsylvania) farm after a four-month illness. He was survived by his wife, Elizabeth Caldwell Rogers, and daughter, Elizabeth Hamilton.

Germantown Academy

Germantown Academy

Germantown Academy is America's oldest nonsectarian day school, founded on December 6, 1759 . Germantown Academy is now a K-12 school in the Philadelphia suburb of Fort Washington, having moved from its original Germantown campus in 1965...

named its debate society after Owen J. Roberts in his honor. In addition, a school district near Pottstown, Pennsylvania

Pottstown, Pennsylvania

Pottstown is a borough in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, United States northwest of Philadelphia and southeast of Reading, on the Schuylkill River. Pottstown was laid out in 1752–53 and named Pottsgrove in honor of its founder, John Potts. The old name was abandoned at the time of the...

, the Owen J. Roberts School District, adopted his name.

In 1946 he was the first lay person elected to serve as President of the House of Deputies for the General Convention of the Episcopal Church. He served for one convention.

See also

- List of Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of law clerks of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of United States Chief Justices by time in office

- List of U.S. Supreme Court Justices by time in office

- United States Supreme Court cases during the Hughes Court

- United States Supreme Court cases during the Stone Court

Further reading

- Abraham, Henry J., Justices and Presidents: A Political History of Appointments to the Supreme Court. 3d. ed. (New York: Oxford University PressOxford University PressOxford University Press is the largest university press in the world. It is a department of the University of Oxford and is governed by a group of 15 academics appointed by the Vice-Chancellor known as the Delegates of the Press. They are headed by the Secretary to the Delegates, who serves as...

, 1992). ISBN 0-19-506557-3. - Cushman, Clare, The Supreme Court Justices: Illustrated Biographies,1789-1995 (2nd ed.) (Supreme Court Historical Society), (Congressional QuarterlyCongressional QuarterlyCongressional Quarterly, Inc., or CQ, is a privately owned publishing company that produces a number of publications reporting primarily on the United States Congress...

Books, 2001) ISBN 1568021267; ISBN 9781568021263. - Frank, John P., The Justices of the United States Supreme Court: Their Lives and Major Opinions (Leon Friedman and Fred L. Israel, editors) (Chelsea House Publishers: 1995) ISBN 0791013774, ISBN 978-0791013779.

- Martin, Fenton S. and Goehlert, Robert U., The U.S. Supreme Court: A Bibliography, (Congressional Quarterly Books, 1990). ISBN 0871875543.

- Urofsky, Melvin I., The Supreme Court Justices: A Biographical Dictionary (New York: Garland Publishing 1994). 590 pp. ISBN 0815311761; ISBN 978-0815311768.