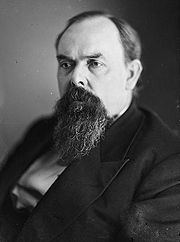

Oliver Hazard Perry Morton

Encyclopedia

Oliver Hazard Perry Throck Morton (August 4, 1823 – November 1, 1877), commonly known as Oliver P. Morton, was a U.S. Republican Party politician from Indiana

. He served as the 14th Governor

of Indiana during the American Civil War, and was a stalwart ally of President Abraham Lincoln

. During the war

, Morton suppressed the Democratic

-controlled Indiana General Assembly

. He exceeded his constitutional

authority by calling out the militia without approval, and during the period of legislative suppression he privately financed the state government through unapproved federal and private loans. He was criticized for arresting and detaining political enemies and suspected southern sympathizers.

During his second term as governor, and after being partially paralyzed by a stroke, he was elected to serve in the U.S. Senate

. He was a leader among the Radical Republican reconstructionists, and supported numerous bills designed to punish and reform the former Southern Confederacy. In 1877, during his second term in the senate, Morton suffered a second debilitating stroke that caused a rapid deterioration in his health; he died later that year. He was mourned nationally and his bier was attended by thousands before his burial in Indianapolis

's Crown Hill Cemetery

.

near the small settlement of Salisbury on August 4, 1823. His family name, Throckmorton, had been shortened to Morton by his grandfather, but the males in the family carried Throck as a middle name. He was named for Oliver Hazard Perry

, the victorious Commodore

in the Battle of Lake Erie

. He disliked his name from an early age, and before beginning his political career he shortened his name to Oliver Perry Morton, from Oliver Hazard Perry Throck Morton. His mother died when he was three, and he was raised by his maternal grandparents. He spent most of his young life living with them in Ohio

.

Morton and his older brother did not complete high school, but together they apprenticed to become hat makers. As a teenager, he moved to Centerville, Indiana

to take up his trade. After four years in the business he became dissatisfied with his profession and decided to instead pursue a career in law. He enrolled at Miami University

in 1843 and studied there until 1844. He then briefly attended Cincinnati College to continue his law studies. In 1845 he returned to Centerville where he was admitted to the bar. He formed a law practice with Judge Newman and became a successful and moderately wealthy attorney. Morton married Lucinda Burbank the same year he returned to Centerville; together the couple had five children, but only two survived infancy.

for all of his adult life, but living in a region dominated by the Whig Party

he had little hope of any political career without a change of party.

After the repeal of the Missouri Compromise

the Democratic Party began to go through a major division and Morton sided with the anti-slavery

wing. With the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act

, the state party began to expel anti-slavery members, including Morton. Morton, along with many other expelled and disaffected Democrats joined the Know-Nothing Party in 1854 and ran is its candidate for governor against Ashbel P. Willard

, but was defeated. He switched parties again and moved to the Republican Party following the collapse of Know-Nothing party. He was one of the founders of the Republican Party, serving as a delegate to the 1856 Republican Party Convention in Pittsburgh. His speeches against slavery made him popular among the party in Indiana. He was noted for his "plain and convincing" manner of speaking, his contemporaries said he was not "eloquent or witty", but rather "logical and reasonable". He was nominated to be the Republican candidate for Governor of Indiana that year, winning a unanimous vote at the state convention. Despite a hard fought campaign, he lost the general election to Democratic state senator Ashbel P. Willard

.

The Republicans nominated Morton for lieutenant governor in 1860 on a ticket with the more popular Henry S. Lane as governor. The two men were both popular in the party, and neither wanted to run against the other in the convention primary and damage their chances for victory in the general election. The party leaders had arranged that upon their victory, the General Assembly would elect Lane to the U.S. Senate and Morton would become governor, assuming that the Republicans took control of the assembly. The campaign was long and focused primarily on the prevailing issues of the nation and the looming possibility of a Civil War. The day after the inauguration, Lane was chosen by the General Assembly for a senate seat. He resigned immediately and Morton succeeded to become governor.

during the Civil War

. He raised men and money for the Union army, and successfully suppressed Indiana's Confederate

sympathizers. He was the leader of the Republican Party in the state, and confronted the Democrats, especially the peace wing (called "Copperheads")

During his early tenure as governor, Morton believed that war was inevitable and began to prepare the state for it. He appointed men to cabinet positions who were well known to be against any compromise with the southern states. He established a state arsenal and employed seven hundred men to produce ammunition and weapons without legislative permission and made many other preparations for the war to come. When open war finally broke out on April 12, 1861, he telegraphed President Abraham Lincoln

three days later to announce that he already had 10,000 soldiers under arms ready to suppress the rebellion.

Lincoln and Morton maintained a close alliance during the war, although Lincoln was wary at times of Morton's ruthlessness. Lincoln once said of Morton that he was "at times the shrewdest person I know." Morton went to great lengths to ensure that Indiana was contributing as much as possible to the war effort. Governor Morton wrote to Lincoln claiming that "no other free state is so populated with southerners", and that they kept Morton from being as forceful against secession as he wanted to be. In 1862, he attended the Loyal War Governors' Conference

in Altoona, Pennsylvania

, organized by Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Gregg Curtin

, that gave Lincoln the support needed for his Emancipation Proclamation

.

became an issue in 1862 the Republicans suffered a major defeat in the mid-term elections, and he lost the support of the strong Democrat majority in the legislature. Before the new legislature had met, Morton began circulating reports that they intended to secede from the Union, instigate riots, and were harboring southern spies. The atmosphere created by the accusations only worsened tensions between the two parties and guaranteed a confrontation, which was probably already inevitable.

Morton had already made several unconstitutional moves, including the establishment of the state arsenal, and the Democrats decided to attempt to rein him in. When the legislature sought to remove the state militia from his command and transfer it to a state board of Democratic commissioners, Morton immediately broke up the General Assembly. He feared that once in control of militia, the Democrats might attempt to overthrow him and secede from the Union. He issued secret instructions to Republican legislators, asking them to stay away from the capitol to prevent the General Assembly from attaining the quorum

needed for the body to pass any legislation. With Morton's aid, the Republicans fled to Madison

where they could quickly flee into Kentucky

should the Democrats attempt to forcibly return them to the capitol.

No appropriations bill had been passed yet, and the government quickly neared bankruptcy. The Democrats assumed that Morton would be forced to call a special session and recall the Republicans to fix the situation, at which time they could again press their measures to weaken the governor. Morton was aware of their plans, and acted accordingly. Going beyond his constitutional powers

, Morton solicited millions of dollars in federal and private loans. His move to subvert the legislature was successful, and Morton was able to privately fund the state government and the war effort in Indiana. James Lanier

gave Morton funds to pay for maintenance on the state's debt until the state could being collecting revenue again.

There was considerable rage among the Democrats, who launched a vicious attack on Morton, who responded by accusing them of treason. Following the suppression of the General Assembly in 1862, Morton asked General Henry B. Carrington

for assistance in organizing the state's levies for service. Morton established an intelligence network headed by Carrington to deal with rebel sympathizers, the Knights of the Golden Circle

, Democrats, and anyone who opposed the Union war effort. While Carrington succeeded in keeping the state secure, his operatives also carried out arbitrary arrests, suppressed freedom of speech and freedom of association, and generally maintained a repressive control of the southern-sympathetic minority. In one incident, Morton had soldiers disrupt a Democratic state convention in an incident that would later be referred to as the Battle of Pogue's Run

. Many leaders of the Democratic Party were arrested, detained, or threatened. He urged pro-war Democrats to abandon their party in the name of unity for the duration of the war, and met with some success. Former governor Joseph A. Wright

was among the Democrats that had been expelled from the party, and in an attempt to show his bipartisanship, Morton appointed him to the Senate.

In reaction to his actions cracking down on dissent, the Indiana Democratic Party called Morton a "Dictator" and an "Underhanded Mobster" while Republicans countered that the Democrats were using "treasonable and obstructionist tactics in the conduct of the war". Morton illegally—without approval from the legislature—called out the state militia in July 1863 to counter Morgan's Raid

. Large-scale support for the Confederacy among Golden Circle members and Southern Hoosiers in general fell away after Morgan's Raid, when Confederate raiders ransacked many homes bearing the banners of the Golden Circle, despite their proclaimed support for the Confederates. When Hoosiers failed to rise in large numbers in support of the raid, Morton slowed his crackdown on Confederate sympathizers, theorizing that because they had failed to come to Morgan's aid in large numbers, they would similarly fail to come to the aid of a larger invasion.

One notable thing historians record from this period was the honesty with which the government was run. All of the borrowed money was accounted for with no graft

or corruption and all was repaid in the years after the war. It was by these honest actions that Morton was able to avoid repercussions when the legislature finally was permitted to reconvene—this time with a new Republican majority.

Morton was reelected to office, defeating Democrat and longtime friend Joseph McDonald

by over 20,000 votes. Although the campaign was conducted in time of war, with both parties strongly opposing the other, both Morton and McDonald remained friends after the campaign and later served together in the U.S. Senate. Many Democrats claimed that Morton had rigged the election because Republicans retook the majority in both houses of the Assembly.

Morton was partially crippled by a paralytic stroke in October 1865 which incapacitated him for a time. For treatment, Morton traveled to Europe where he sought the assistance of several specialists, but none were able to help his paralysis. During his recovery time Lieutenant Governor

Conrad Baker

served as acting governor. With the war ending, Baker oversaw the demobilization of most of the state's forces. Morton returned to the governorship in March 1866, but he was never again able to walk without assistance.

Morton was in the Senate during Reconstruction and he supported most of the radical and repressive plans for punishing the southern states. Early in his first term in the Senate he supported legislation to eliminate all civil government in the southern states and impose a military government. He also supported legislation to void the southern states' constitutions and impose new ones. Among other things, he supported removing the right to vote from the majority of southerners and tripling the cotton tax. He supported the impeachment

of President Andrew Johnson

for his "moderate" views on reconstruction and openly voiced his disappointed when the impeachment failed. Although he had delivered a speech against giving blacks the right to vote in 1865, by 1870 Morton had completely changed his position and supported full suffrage for the former slave population. He is quoted as saying "I confess, and I do it without shame, that I have been educated by the great events of War." He championed the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment

, and when the Democrats began to resign from the Senate during its debate to prevent quorum from being attained, Morton was the engineer of the maneuvering that kept the bill in the docket and allowed it to be passed.

After the new administration of President Ulysses S. Grant

came to power in 1870, Morton was offered the position of Ambassador to Great Britain, but he refused. The Indiana General Assembly was controlled by the Democrats and he feared a Democrat would be elected to his seat.

made him controversial, he supported inflating the currency by printing money to pay down the war debt. He started the term by leading the Senate's support of the inflation bill that was vetoed by President Grant

.

Morton was a contender for the 1876 Republican nomination for President at the Cincinnati Convention where his name was offered by Richard W. Thompson

. His position on issuing paper money to inflate the currency, combined with his failing health, hurt him in his bid for the Republican presidential nomination among the convention delegates. His vote total placed him second to James G. Blaine

on the early ballots. By the sixth ballot he had slipped to fourth place and on the next vote nearly all the anti-Blaine delegates, including Morton's, united to give Rutherford B. Hayes

the nomination.

In 1877, Morton was named to lead a committee to investigate charges of bribery made against La Fayette Grover

In 1877, Morton was named to lead a committee to investigate charges of bribery made against La Fayette Grover

, a newly elected senator from Oregon

. The committee spent eighteen days in Oregon holding hearings and investigations. On the return trip, Morton detoured to San Francisco for a rest and visit. On the night of August 6, after eating dinner, he suffered a severe stroke that paralyzed the left side of his body. The next day he was taken by train to Cheyenne

, Dakota Territory

, where he was met by his brother-in-law John A. Burbank

, the governor of the territory. Morton was accompanied by him to the home of his mother-in-law in Richmond, Indiana

. He remained there to recover until October 15 when he was again moved to his own home in Indianapolis. He remained there, surrounded by his family, until his death on November 1, 1877.

Morton's remains were laid in state in the Indianapolis court house for three days after his death before being moved to Roberts Park Church where his funeral was held. His ceremony was attended by many dignitaries from across the United States. President Grant ordered all flags to half-staff. The church could not hold the crowd and the thousands of mourners waited outside and followed in a long procession to view the burial in Crown Hill Cemetery

.

Despite holding many positions that angered his opponents, Morton was highly regarded for remaining clean of graft during the war period when corruption was commonplace. For his honest conduct he was offered the thanks of the Indiana General Assembly and others on numerous occasions. Morton succeeded in raising Indiana to national prominence during his lifetime. The state and its citizens were the common subject of jokes to the eastern states, but much of that ceased after the war.

as one of Indiana's two statues on the National Statuary Hall Collection

. There are also two statues of him in downtown Indianapolis, in front of the Indiana Statehouse and as part of the Indiana Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument

on Monument Circle. Another statue stands on the second floor of the Wayne County Courthouse in Richmond, Indiana

where a previous high school was named for him and the central section of the current high school is named Morton Hall in his honor.

Morton Senior High School in Hammond, Indiana

, home of the Morton Governors, is named after him, as is Morton County, Kansas

.

A statue of Governor Morton also serves as the State of Indiana's memorial at Vicksburg National Military Park

in Vicksburg, Mississippi

, in honor of his role as a powerful wartime governor.

The annual yearbook

of Centerville Senior High School

in Centerville, Indiana

is called The Mortonian in honor of Gov. Morton.

Indiana

Indiana is a US state, admitted to the United States as the 19th on December 11, 1816. It is located in the Midwestern United States and Great Lakes Region. With 6,483,802 residents, the state is ranked 15th in population and 16th in population density. Indiana is ranked 38th in land area and is...

. He served as the 14th Governor

Governor of Indiana

The Governor of Indiana is the chief executive of the state of Indiana. The governor is elected to a four-year term, and responsible for overseeing the day-to-day management of the functions of many agencies of the Indiana state government. The governor also shares power with other statewide...

of Indiana during the American Civil War, and was a stalwart ally of President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln was the 16th President of the United States, serving from March 1861 until his assassination in April 1865. He successfully led his country through a great constitutional, military and moral crisis – the American Civil War – preserving the Union, while ending slavery, and...

. During the war

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

, Morton suppressed the Democratic

Democratic Party (United States)

The Democratic Party is one of two major contemporary political parties in the United States, along with the Republican Party. The party's socially liberal and progressive platform is largely considered center-left in the U.S. political spectrum. The party has the lengthiest record of continuous...

-controlled Indiana General Assembly

Indiana General Assembly

The Indiana General Assembly is the state legislature, or legislative branch, of the state of Indiana. It is a bicameral legislature that consists of a lower house, the Indiana House of Representatives, and an upper house, the Indiana Senate...

. He exceeded his constitutional

Constitution of Indiana

There have been two Constitutions of the State of Indiana. The first constitution was created when the Territory of Indiana sent forty-three delegates to a constitutional convention on June 10, 1816 to establish a constitution for the proposed State of Indiana after the United States Congress had...

authority by calling out the militia without approval, and during the period of legislative suppression he privately financed the state government through unapproved federal and private loans. He was criticized for arresting and detaining political enemies and suspected southern sympathizers.

During his second term as governor, and after being partially paralyzed by a stroke, he was elected to serve in the U.S. Senate

United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper house of the bicameral legislature of the United States, and together with the United States House of Representatives comprises the United States Congress. The composition and powers of the Senate are established in Article One of the U.S. Constitution. Each...

. He was a leader among the Radical Republican reconstructionists, and supported numerous bills designed to punish and reform the former Southern Confederacy. In 1877, during his second term in the senate, Morton suffered a second debilitating stroke that caused a rapid deterioration in his health; he died later that year. He was mourned nationally and his bier was attended by thousands before his burial in Indianapolis

Indianapolis

Indianapolis is the capital of the U.S. state of Indiana, and the county seat of Marion County, Indiana. As of the 2010 United States Census, the city's population is 839,489. It is by far Indiana's largest city and, as of the 2010 U.S...

's Crown Hill Cemetery

Crown Hill Cemetery

Crown Hill Cemetery, located at 700 West 38th Street in Indianapolis, is the third largest non-governmental cemetery in the United States at . It contains of paved road, over 150 species of trees and plants, over 185,000 graves, and services roughly 1,500 burials per year. It sits on the highest...

.

Family and background

Morton was an Indiana native born in Wayne CountyWayne County, Indiana

Wayne County is a county located in the U.S. state of Indiana. As of the 2010 census, the population was 68,917. The county seat is Richmond.-History:...

near the small settlement of Salisbury on August 4, 1823. His family name, Throckmorton, had been shortened to Morton by his grandfather, but the males in the family carried Throck as a middle name. He was named for Oliver Hazard Perry

Oliver Hazard Perry

United States Navy Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry was born in South Kingstown, Rhode Island , the son of USN Captain Christopher Raymond Perry and Sarah Wallace Alexander, a direct descendant of William Wallace...

, the victorious Commodore

Commodore (USN)

Commodore was an early title and later a rank in the United States Navy and United States Coast Guard and a current honorary title in the U.S. Navy with an intricate history. Because the U.S. Congress was originally unwilling to authorize more than four ranks until 1862, considerable importance...

in the Battle of Lake Erie

Battle of Lake Erie

The Battle of Lake Erie, sometimes called the Battle of Put-in-Bay, was fought on 10 September 1813, in Lake Erie off the coast of Ohio during the War of 1812. Nine vessels of the United States Navy defeated and captured six vessels of Great Britain's Royal Navy...

. He disliked his name from an early age, and before beginning his political career he shortened his name to Oliver Perry Morton, from Oliver Hazard Perry Throck Morton. His mother died when he was three, and he was raised by his maternal grandparents. He spent most of his young life living with them in Ohio

Ohio

Ohio is a Midwestern state in the United States. The 34th largest state by area in the U.S.,it is the 7th‑most populous with over 11.5 million residents, containing several major American cities and seven metropolitan areas with populations of 500,000 or more.The state's capital is Columbus...

.

Morton and his older brother did not complete high school, but together they apprenticed to become hat makers. As a teenager, he moved to Centerville, Indiana

Centerville, Indiana

Centerville is a town in Center Township, Wayne County, Indiana, United States. The population was 2,552 at the 2010 census.-Geography:Centerville is located at , at an altitude of 1,014 feet . U.S...

to take up his trade. After four years in the business he became dissatisfied with his profession and decided to instead pursue a career in law. He enrolled at Miami University

Miami University

Miami University is a coeducational public research university located in Oxford, Ohio, United States. Founded in 1809, it is the 10th oldest public university in the United States and the second oldest university in Ohio, founded four years after Ohio University. In its 2012 edition, U.S...

in 1843 and studied there until 1844. He then briefly attended Cincinnati College to continue his law studies. In 1845 he returned to Centerville where he was admitted to the bar. He formed a law practice with Judge Newman and became a successful and moderately wealthy attorney. Morton married Lucinda Burbank the same year he returned to Centerville; together the couple had five children, but only two survived infancy.

Early political career

In 1852 Morton, at the urging of Judge Newman, campaigned and was elected to serve as a circuit court judge but resigned after only a year; he found that he preferred practicing law. Morton had been a DemocratDemocratic Party (United States)

The Democratic Party is one of two major contemporary political parties in the United States, along with the Republican Party. The party's socially liberal and progressive platform is largely considered center-left in the U.S. political spectrum. The party has the lengthiest record of continuous...

for all of his adult life, but living in a region dominated by the Whig Party

Whig Party (United States)

The Whig Party was a political party of the United States during the era of Jacksonian democracy. Considered integral to the Second Party System and operating from the early 1830s to the mid-1850s, the party was formed in opposition to the policies of President Andrew Jackson and his Democratic...

he had little hope of any political career without a change of party.

After the repeal of the Missouri Compromise

Missouri Compromise

The Missouri Compromise was an agreement passed in 1820 between the pro-slavery and anti-slavery factions in the United States Congress, involving primarily the regulation of slavery in the western territories. It prohibited slavery in the former Louisiana Territory north of the parallel 36°30'...

the Democratic Party began to go through a major division and Morton sided with the anti-slavery

Abolitionism

Abolitionism is a movement to end slavery.In western Europe and the Americas abolitionism was a movement to end the slave trade and set slaves free. At the behest of Dominican priest Bartolomé de las Casas who was shocked at the treatment of natives in the New World, Spain enacted the first...

wing. With the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act

Kansas-Nebraska Act

The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska, opening new lands for settlement, and had the effect of repealing the Missouri Compromise of 1820 by allowing settlers in those territories to determine through Popular Sovereignty if they would allow slavery within...

, the state party began to expel anti-slavery members, including Morton. Morton, along with many other expelled and disaffected Democrats joined the Know-Nothing Party in 1854 and ran is its candidate for governor against Ashbel P. Willard

Ashbel P. Willard

Ashbel Parsons Willard was state senator, the 12th Lieutenant Governor, and the 11th Governor of the U.S. state of Indiana. His terms in office were marked by increasingly severe partisanship leading to the breakup of the state Democratic Party in the years leading up to the American Civil War...

, but was defeated. He switched parties again and moved to the Republican Party following the collapse of Know-Nothing party. He was one of the founders of the Republican Party, serving as a delegate to the 1856 Republican Party Convention in Pittsburgh. His speeches against slavery made him popular among the party in Indiana. He was noted for his "plain and convincing" manner of speaking, his contemporaries said he was not "eloquent or witty", but rather "logical and reasonable". He was nominated to be the Republican candidate for Governor of Indiana that year, winning a unanimous vote at the state convention. Despite a hard fought campaign, he lost the general election to Democratic state senator Ashbel P. Willard

Ashbel P. Willard

Ashbel Parsons Willard was state senator, the 12th Lieutenant Governor, and the 11th Governor of the U.S. state of Indiana. His terms in office were marked by increasingly severe partisanship leading to the breakup of the state Democratic Party in the years leading up to the American Civil War...

.

The Republicans nominated Morton for lieutenant governor in 1860 on a ticket with the more popular Henry S. Lane as governor. The two men were both popular in the party, and neither wanted to run against the other in the convention primary and damage their chances for victory in the general election. The party leaders had arranged that upon their victory, the General Assembly would elect Lane to the U.S. Senate and Morton would become governor, assuming that the Republicans took control of the assembly. The campaign was long and focused primarily on the prevailing issues of the nation and the looming possibility of a Civil War. The day after the inauguration, Lane was chosen by the General Assembly for a senate seat. He resigned immediately and Morton succeeded to become governor.

Governor

War effort

Morton served as governor of Indiana for six years (1861–1867) and strongly supported the UnionUnion (American Civil War)

During the American Civil War, the Union was a name used to refer to the federal government of the United States, which was supported by the twenty free states and five border slave states. It was opposed by 11 southern slave states that had declared a secession to join together to form the...

during the Civil War

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

. He raised men and money for the Union army, and successfully suppressed Indiana's Confederate

Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America was a government set up from 1861 to 1865 by 11 Southern slave states of the United States of America that had declared their secession from the U.S...

sympathizers. He was the leader of the Republican Party in the state, and confronted the Democrats, especially the peace wing (called "Copperheads")

During his early tenure as governor, Morton believed that war was inevitable and began to prepare the state for it. He appointed men to cabinet positions who were well known to be against any compromise with the southern states. He established a state arsenal and employed seven hundred men to produce ammunition and weapons without legislative permission and made many other preparations for the war to come. When open war finally broke out on April 12, 1861, he telegraphed President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln was the 16th President of the United States, serving from March 1861 until his assassination in April 1865. He successfully led his country through a great constitutional, military and moral crisis – the American Civil War – preserving the Union, while ending slavery, and...

three days later to announce that he already had 10,000 soldiers under arms ready to suppress the rebellion.

Lincoln and Morton maintained a close alliance during the war, although Lincoln was wary at times of Morton's ruthlessness. Lincoln once said of Morton that he was "at times the shrewdest person I know." Morton went to great lengths to ensure that Indiana was contributing as much as possible to the war effort. Governor Morton wrote to Lincoln claiming that "no other free state is so populated with southerners", and that they kept Morton from being as forceful against secession as he wanted to be. In 1862, he attended the Loyal War Governors' Conference

War Governors' Conference

The Loyal War Governors' Conference was an important political event of the American Civil War. It was held at the Logan House Hotel in Altoona, Pennsylvania on September 24 and 25, 1862. Thirteen governors of Union states came together to discuss the war effort, state troop quotas, and the...

in Altoona, Pennsylvania

Altoona, Pennsylvania

-History:A major railroad town, Altoona was founded by the Pennsylvania Railroad in 1849 as the site for a shop complex. Altoona was incorporated as a borough on February 6, 1854, and as a city under legislation approved on April 3, 1867, and February 8, 1868...

, organized by Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Gregg Curtin

Andrew Gregg Curtin

Andrew Gregg Curtin was a U.S. lawyer and politician. He served as the Governor of Pennsylvania during the Civil War.-Biography:...

, that gave Lincoln the support needed for his Emancipation Proclamation

Emancipation Proclamation

The Emancipation Proclamation is an executive order issued by United States President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, during the American Civil War using his war powers. It proclaimed the freedom of 3.1 million of the nation's 4 million slaves, and immediately freed 50,000 of them, with nearly...

.

Conflict with the General Assembly

Morton was able to keep the state united during the first phase of the war, but once emancipationEmancipation

Emancipation means the act of setting an individual or social group free or making equal to citizens in a political society.Emancipation may also refer to:* Emancipation , a champion Australian thoroughbred racehorse foaled in 1979...

became an issue in 1862 the Republicans suffered a major defeat in the mid-term elections, and he lost the support of the strong Democrat majority in the legislature. Before the new legislature had met, Morton began circulating reports that they intended to secede from the Union, instigate riots, and were harboring southern spies. The atmosphere created by the accusations only worsened tensions between the two parties and guaranteed a confrontation, which was probably already inevitable.

Morton had already made several unconstitutional moves, including the establishment of the state arsenal, and the Democrats decided to attempt to rein him in. When the legislature sought to remove the state militia from his command and transfer it to a state board of Democratic commissioners, Morton immediately broke up the General Assembly. He feared that once in control of militia, the Democrats might attempt to overthrow him and secede from the Union. He issued secret instructions to Republican legislators, asking them to stay away from the capitol to prevent the General Assembly from attaining the quorum

Quorum

A quorum is the minimum number of members of a deliberative assembly necessary to conduct the business of that group...

needed for the body to pass any legislation. With Morton's aid, the Republicans fled to Madison

Madison, Indiana

As of the census of 2000, there were 12,004 people, 5,092 households, and 3,085 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,402.9 people per square mile . There were 5,597 housing units at an average density of 654.1 per square mile...

where they could quickly flee into Kentucky

Kentucky

The Commonwealth of Kentucky is a state located in the East Central United States of America. As classified by the United States Census Bureau, Kentucky is a Southern state, more specifically in the East South Central region. Kentucky is one of four U.S. states constituted as a commonwealth...

should the Democrats attempt to forcibly return them to the capitol.

No appropriations bill had been passed yet, and the government quickly neared bankruptcy. The Democrats assumed that Morton would be forced to call a special session and recall the Republicans to fix the situation, at which time they could again press their measures to weaken the governor. Morton was aware of their plans, and acted accordingly. Going beyond his constitutional powers

Constitution of Indiana

There have been two Constitutions of the State of Indiana. The first constitution was created when the Territory of Indiana sent forty-three delegates to a constitutional convention on June 10, 1816 to establish a constitution for the proposed State of Indiana after the United States Congress had...

, Morton solicited millions of dollars in federal and private loans. His move to subvert the legislature was successful, and Morton was able to privately fund the state government and the war effort in Indiana. James Lanier

James Lanier

James Franklin Doughty Lanier was a entrepreneur who lived in Madison, Indiana prior to the outbreak of the American Civil War . Lanier became a wealthy banker with interests in pork packing, the railroads, and real-estate.-Biography:James Lanier was born in 1800 in Beaufort County, North Carolina...

gave Morton funds to pay for maintenance on the state's debt until the state could being collecting revenue again.

There was considerable rage among the Democrats, who launched a vicious attack on Morton, who responded by accusing them of treason. Following the suppression of the General Assembly in 1862, Morton asked General Henry B. Carrington

Henry B. Carrington

Henry Beebee Carrington was a lawyer, professor, prolific author, and an officer in the United States Army during the American Civil War and in the Old West during Red Cloud's War...

for assistance in organizing the state's levies for service. Morton established an intelligence network headed by Carrington to deal with rebel sympathizers, the Knights of the Golden Circle

Knights of the Golden Circle

The Knights of the Golden Circle was a secret society. Some researchers believe the objective of the KGC was to prepare the way for annexation of a golden circle of territories in Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean for inclusion in the United States as slave states...

, Democrats, and anyone who opposed the Union war effort. While Carrington succeeded in keeping the state secure, his operatives also carried out arbitrary arrests, suppressed freedom of speech and freedom of association, and generally maintained a repressive control of the southern-sympathetic minority. In one incident, Morton had soldiers disrupt a Democratic state convention in an incident that would later be referred to as the Battle of Pogue's Run

Battle of Pogue's Run

The so-called Battle of Pogue's Run took place in Indianapolis, Indiana on May 20, 1863. It was believed that many of the delegates to the Democrat state convention had firearms, in the hope of inciting a rebellion. Union soldiers entered the hall that the convention took place, and found...

. Many leaders of the Democratic Party were arrested, detained, or threatened. He urged pro-war Democrats to abandon their party in the name of unity for the duration of the war, and met with some success. Former governor Joseph A. Wright

Joseph A. Wright

Joseph Albert Wright was the tenth Governor of the U.S. state of Indiana from December 5, 1849 to January 12, 1857, most noted for his opposition to banking. His positions created a rift between him and the Indiana General Assembly who overrode all of his anti-banking vetoes...

was among the Democrats that had been expelled from the party, and in an attempt to show his bipartisanship, Morton appointed him to the Senate.

In reaction to his actions cracking down on dissent, the Indiana Democratic Party called Morton a "Dictator" and an "Underhanded Mobster" while Republicans countered that the Democrats were using "treasonable and obstructionist tactics in the conduct of the war". Morton illegally—without approval from the legislature—called out the state militia in July 1863 to counter Morgan's Raid

Morgan's Raid

Morgan's Raid was a highly publicized incursion by Confederate cavalry into the Northern states of Indiana and Ohio during the American Civil War. The raid took place from June 11–July 26, 1863, and is named for the commander of the Confederates, Brig. Gen...

. Large-scale support for the Confederacy among Golden Circle members and Southern Hoosiers in general fell away after Morgan's Raid, when Confederate raiders ransacked many homes bearing the banners of the Golden Circle, despite their proclaimed support for the Confederates. When Hoosiers failed to rise in large numbers in support of the raid, Morton slowed his crackdown on Confederate sympathizers, theorizing that because they had failed to come to Morgan's aid in large numbers, they would similarly fail to come to the aid of a larger invasion.

One notable thing historians record from this period was the honesty with which the government was run. All of the borrowed money was accounted for with no graft

Political corruption

Political corruption is the use of legislated powers by government officials for illegitimate private gain. Misuse of government power for other purposes, such as repression of political opponents and general police brutality, is not considered political corruption. Neither are illegal acts by...

or corruption and all was repaid in the years after the war. It was by these honest actions that Morton was able to avoid repercussions when the legislature finally was permitted to reconvene—this time with a new Republican majority.

Second term

In 1864 the war was nearing its end, though many saw no end in sight. The state constitution forbade a governor to serve more than four years in any eight year period, but Morton claimed that since he was elected as Lieutenant Governor and had only been completing Lane's term, he was eligible to run. The Democrats were furious again, and a bitter campaign was launched against Morton. Morton did not do a great deal of campaigning, but instead sought to have soldiers returned home to vote for him.Morton was reelected to office, defeating Democrat and longtime friend Joseph McDonald

Joseph E. McDonald

Joseph Ewing McDonald was a United States Representative and Senator from Indiana. Born in Butler County, Ohio, he moved with his mother to Montgomery County, Indiana in 1826 and apprenticed to the saddler’s trade when twelve years of age in Lafayette, Indiana...

by over 20,000 votes. Although the campaign was conducted in time of war, with both parties strongly opposing the other, both Morton and McDonald remained friends after the campaign and later served together in the U.S. Senate. Many Democrats claimed that Morton had rigged the election because Republicans retook the majority in both houses of the Assembly.

Morton was partially crippled by a paralytic stroke in October 1865 which incapacitated him for a time. For treatment, Morton traveled to Europe where he sought the assistance of several specialists, but none were able to help his paralysis. During his recovery time Lieutenant Governor

Lieutenant Governor of Indiana

The Lieutenant Governor of Indiana is a constitutional office in the US State of Indiana. Republican Becky Skillman, whose term expires in January 2013, is the incumbent...

Conrad Baker

Conrad Baker

Conrad Baker was a state representative, 15th Lieutenant Governor, and the 15th Governor of the U.S. state of Indiana from 1867 to 1873...

served as acting governor. With the war ending, Baker oversaw the demobilization of most of the state's forces. Morton returned to the governorship in March 1866, but he was never again able to walk without assistance.

Senator

First term

In 1867, Morton was elected by the General Assembly to serve as a United States Senator. He resigned from his Governor post that same year, again turning over the government to Lieutenant Governor Baker. In the Senate he first became a member of the foreign affairs committee and quickly grew to become a party leader. He was also made chairman of the Committee of Privileges and Elections. Because of his stroke, Morton always sat while delivering his speeches, but he was noted by other senators for his effectiveness in speaking and debating.Morton was in the Senate during Reconstruction and he supported most of the radical and repressive plans for punishing the southern states. Early in his first term in the Senate he supported legislation to eliminate all civil government in the southern states and impose a military government. He also supported legislation to void the southern states' constitutions and impose new ones. Among other things, he supported removing the right to vote from the majority of southerners and tripling the cotton tax. He supported the impeachment

Impeachment

Impeachment is a formal process in which an official is accused of unlawful activity, the outcome of which, depending on the country, may include the removal of that official from office as well as other punishment....

of President Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson was the 17th President of the United States . As Vice-President of the United States in 1865, he succeeded Abraham Lincoln following the latter's assassination. Johnson then presided over the initial and contentious Reconstruction era of the United States following the American...

for his "moderate" views on reconstruction and openly voiced his disappointed when the impeachment failed. Although he had delivered a speech against giving blacks the right to vote in 1865, by 1870 Morton had completely changed his position and supported full suffrage for the former slave population. He is quoted as saying "I confess, and I do it without shame, that I have been educated by the great events of War." He championed the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment

Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution prohibits each government in the United States from denying a citizen the right to vote based on that citizen's "race, color, or previous condition of servitude"...

, and when the Democrats began to resign from the Senate during its debate to prevent quorum from being attained, Morton was the engineer of the maneuvering that kept the bill in the docket and allowed it to be passed.

After the new administration of President Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant was the 18th President of the United States as well as military commander during the Civil War and post-war Reconstruction periods. Under Grant's command, the Union Army defeated the Confederate military and ended the Confederate States of America...

came to power in 1870, Morton was offered the position of Ambassador to Great Britain, but he refused. The Indiana General Assembly was controlled by the Democrats and he feared a Democrat would be elected to his seat.

Second term

Morton was reelected to the Senate in 1873 and began his second term in 1874. Morton's stand on paper moneyPaper Money

Paper Money is the second album by the band Montrose. It was released in 1974 and was the band's last album to feature Sammy Hagar as lead vocalist.-History:...

made him controversial, he supported inflating the currency by printing money to pay down the war debt. He started the term by leading the Senate's support of the inflation bill that was vetoed by President Grant

Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant was the 18th President of the United States as well as military commander during the Civil War and post-war Reconstruction periods. Under Grant's command, the Union Army defeated the Confederate military and ended the Confederate States of America...

.

Morton was a contender for the 1876 Republican nomination for President at the Cincinnati Convention where his name was offered by Richard W. Thompson

Richard W. Thompson

Richard Wigginton Thompson was an American politician.Thompson was born in Culpeper County, Virginia. He left Virginia in 1831 and lived briefly in Louisville, Kentucky before finally settling in Lawrence County, Indiana. There, he taught school, kept a store, and studied law at night...

. His position on issuing paper money to inflate the currency, combined with his failing health, hurt him in his bid for the Republican presidential nomination among the convention delegates. His vote total placed him second to James G. Blaine

James G. Blaine

James Gillespie Blaine was a U.S. Representative, Speaker of the United States House of Representatives, U.S. Senator from Maine, two-time Secretary of State...

on the early ballots. By the sixth ballot he had slipped to fourth place and on the next vote nearly all the anti-Blaine delegates, including Morton's, united to give Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes was the 19th President of the United States . As president, he oversaw the end of Reconstruction and the United States' entry into the Second Industrial Revolution...

the nomination.

Death

La Fayette Grover

La Fayette Grover was a Democratic politician and lawyer from the US state of Oregon. He was the fourth Governor of Oregon, serving from 1870 to 1877...

, a newly elected senator from Oregon

Oregon

Oregon is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. It is located on the Pacific coast, with Washington to the north, California to the south, Nevada on the southeast and Idaho to the east. The Columbia and Snake rivers delineate much of Oregon's northern and eastern...

. The committee spent eighteen days in Oregon holding hearings and investigations. On the return trip, Morton detoured to San Francisco for a rest and visit. On the night of August 6, after eating dinner, he suffered a severe stroke that paralyzed the left side of his body. The next day he was taken by train to Cheyenne

Cheyenne, Wyoming

Cheyenne is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Wyoming and the county seat of Laramie County. It is the principal city of the Cheyenne, Wyoming, Metropolitan Statistical Area which encompasses all of Laramie County. The population is 59,466 at the 2010 census. Cheyenne is the...

, Dakota Territory

Dakota Territory

The Territory of Dakota was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from March 2, 1861, until November 2, 1889, when the final extent of the reduced territory was split and admitted to the Union as the states of North and South Dakota.The Dakota Territory consisted of...

, where he was met by his brother-in-law John A. Burbank

John A. Burbank

John Albyne Burbank was an American businessman and the fourth Governor of Dakota Territory.Burbank was born at Centerville, Wayne County, Indiana. After finishing school, he entered into the merchandising business with his father. In 1853, Burbank laid out the site of Falls City, Nebraska, and...

, the governor of the territory. Morton was accompanied by him to the home of his mother-in-law in Richmond, Indiana

Richmond, Indiana

Richmond is a city largely within Wayne Township, Wayne County, in east central Indiana, United States, which borders Ohio. The city also includes the Richmond Municipal Airport, which is in Boston Township and separated from the rest of the city...

. He remained there to recover until October 15 when he was again moved to his own home in Indianapolis. He remained there, surrounded by his family, until his death on November 1, 1877.

Morton's remains were laid in state in the Indianapolis court house for three days after his death before being moved to Roberts Park Church where his funeral was held. His ceremony was attended by many dignitaries from across the United States. President Grant ordered all flags to half-staff. The church could not hold the crowd and the thousands of mourners waited outside and followed in a long procession to view the burial in Crown Hill Cemetery

Crown Hill Cemetery

Crown Hill Cemetery, located at 700 West 38th Street in Indianapolis, is the third largest non-governmental cemetery in the United States at . It contains of paved road, over 150 species of trees and plants, over 185,000 graves, and services roughly 1,500 burials per year. It sits on the highest...

.

Legacy

Policies and criticism

Morton gained many critics during his long tenure in government service. He was criticized and derided for the manner in which he ran Indiana during the Civil War. He openly suppressed freedom of speech, arrested and detained political enemies, and violated the state and federal constitutions on numerous occasions. In the Senate he was one of the most radical reconstruction idealists, and pushed for numerous bills that, by design, had long ranging negative impacts on the development of the southern United States.Despite holding many positions that angered his opponents, Morton was highly regarded for remaining clean of graft during the war period when corruption was commonplace. For his honest conduct he was offered the thanks of the Indiana General Assembly and others on numerous occasions. Morton succeeded in raising Indiana to national prominence during his lifetime. The state and its citizens were the common subject of jokes to the eastern states, but much of that ceased after the war.

Memorials

Morton is memorialized in the United States CapitolUnited States Capitol

The United States Capitol is the meeting place of the United States Congress, the legislature of the federal government of the United States. Located in Washington, D.C., it sits atop Capitol Hill at the eastern end of the National Mall...

as one of Indiana's two statues on the National Statuary Hall Collection

National Statuary Hall Collection

The National Statuary Hall Collection in the United States Capitol comprises statues donated by individual states to honor persons notable in their history...

. There are also two statues of him in downtown Indianapolis, in front of the Indiana Statehouse and as part of the Indiana Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument

Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument (Indianapolis)

The Indiana Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument is a tall neoclassical monument in the center of Indianapolis, Indiana that was designed by German architect Bruno Schmitz and completed in 1901....

on Monument Circle. Another statue stands on the second floor of the Wayne County Courthouse in Richmond, Indiana

Richmond, Indiana

Richmond is a city largely within Wayne Township, Wayne County, in east central Indiana, United States, which borders Ohio. The city also includes the Richmond Municipal Airport, which is in Boston Township and separated from the rest of the city...

where a previous high school was named for him and the central section of the current high school is named Morton Hall in his honor.

Morton Senior High School in Hammond, Indiana

Hammond, Indiana

Hammond is a city in Lake County, Indiana, United States. It is part of the Chicago metropolitan area. The population was 80,830 at the 2010 census.-Geography:Hammond is located at ....

, home of the Morton Governors, is named after him, as is Morton County, Kansas

Morton County, Kansas

Morton County is a county located in the U.S. state of Kansas. As of the 2010 census, the county population was 3,233...

.

A statue of Governor Morton also serves as the State of Indiana's memorial at Vicksburg National Military Park

Vicksburg National Military Park

Vicksburg National Military Park preserves the site of the American Civil War Battle of Vicksburg, waged from May 18 to July 4, 1863. The park, in Vicksburg, Mississippi, and Delta, Louisiana, also commemorates the greater Vicksburg Campaign, which preceded the battle. Reconstructed forts and...

in Vicksburg, Mississippi

Vicksburg, Mississippi

Vicksburg is a city in Warren County, Mississippi, United States. It is the only city in Warren County. It is located northwest of New Orleans on the Mississippi and Yazoo rivers, and due west of Jackson, the state capital. In 1900, 14,834 people lived in Vicksburg; in 1910, 20,814; in 1920,...

, in honor of his role as a powerful wartime governor.

The annual yearbook

Yearbook

A yearbook, also known as an annual, is a book to record, highlight, and commemorate the past year of a school or a book published annually. Virtually all American, Australian and Canadian high schools, most colleges and many elementary and middle schools publish yearbooks...

of Centerville Senior High School

Centerville Senior High School

http://profile.ak.fbcdn.net/hprofile-ak-snc4/hs476.snc4/50512_2224935887_2558470_n.jpgCenterville Senior High School is a high school located in Centerville, Indiana.- Facilities :...

in Centerville, Indiana

Centerville, Indiana

Centerville is a town in Center Township, Wayne County, Indiana, United States. The population was 2,552 at the 2010 census.-Geography:Centerville is located at , at an altitude of 1,014 feet . U.S...

is called The Mortonian in honor of Gov. Morton.

See also

- History of slavery in IndianaHistory of slavery in IndianaSlavery in Indiana occurred between the time of French rule during late seventeenth century and 1826, with a few traces of slavery afterward. When the United States first took control of the region, slavery was tolerated as a necessity to keep peace with the Indians and the French...

- List of Governors of Indiana

External links

- http://www.nps.gov/vick/historyculture/indiana-memorial.htm Information on Perry's statue at Vicksburg National Military Park.