List of inventors killed by their own inventions

Encyclopedia

This is a list of inventors whose deaths were in some manner caused by or related to a product, process, procedure, or other innovation that they invented or designed.

Automotive

- William Nelson (ca. 1879−1903), a General ElectricGeneral ElectricGeneral Electric Company , or GE, is an American multinational conglomerate corporation incorporated in Schenectady, New York and headquartered in Fairfield, Connecticut, United States...

employee, invented a new way to motorize bicyclesMotorized bicycleA motorized bicycle, motorbike, cyclemotor, or vélomoteur is a bicycle with an attached motor and transmission used either to power the vehicle unassisted, or to assist with pedaling. Since it always retains both pedals and a discrete connected drive for rider-powered propulsion, the motorized...

. He then fell off his prototype bike during a test run.

Aviation

- Ismail ibn Hammad al-JawhariIsmail ibn Hammad al-JawhariAbu Nasr Isma'il ibn Hammad al-Jawhari or al-Jauhari was the author of a notable Arabic dictionary. He was born in the city of Farab a.k.a. Otrar in Turkestan . He studied Arabic language first in Baghdad and then among the Arabs of the Hejaz. Then he settled in northern Khorasan...

(died ca. 1003–1010), a Muslim Kazakh TurkicTurkic peoplesThe Turkic peoples are peoples residing in northern, central and western Asia, southern Siberia and northwestern China and parts of eastern Europe. They speak languages belonging to the Turkic language family. They share, to varying degrees, certain cultural traits and historical backgrounds...

scholar from FarabOtrarOtrar or Utrar is a Central Asian ghost town that was a city located along the Silk Road near the current town of Karatau in Kazakhstan. Otrar was an important town in the history of Central Asia, situated on the borders of settled and agricultural civilizations...

, attempted to fly using two wooden wings and a rope. He leapt from the roof of a mosque in Nijabur and fell to his death. - Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier was the first known fatality in an air crash when his Rozière balloonRozière balloonThe Rozière balloon is a type of hybrid balloon that has separate chambers for a non-heated lifting gas as well as a heated lifting gas...

crashed on 15 June 1785 while he and Pierre Romain were attempting to cross the English ChannelEnglish ChannelThe English Channel , often referred to simply as the Channel, is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that separates southern England from northern France, and joins the North Sea to the Atlantic. It is about long and varies in width from at its widest to in the Strait of Dover...

. - Otto LilienthalOtto LilienthalOtto Lilienthal was a German pioneer of human aviation who became known as the Glider King. He was the first person to make well-documented, repeated, successful gliding flights. He followed an experimental approach established earlier by Sir George Cayley...

(1848–1896) died the day after crashing one of his hang gliders. - Franz ReicheltFranz ReicheltFranz Reichelt, also known as Frantz Reichelt or François Reichelt , was an Austrian-born French tailor, inventor and parachuting pioneer, now sometimes referred to as the Flying Tailor, who is remembered for his accidental death by jumping from the Eiffel Tower while testing a wearable parachute...

(1879–1912), a tailorTailorA tailor is a person who makes, repairs, or alters clothing professionally, especially suits and men's clothing.Although the term dates to the thirteenth century, tailor took on its modern sense in the late eighteenth century, and now refers to makers of men's and women's suits, coats, trousers,...

, fell to his death off the first deck of the Eiffel TowerEiffel TowerThe Eiffel Tower is a puddle iron lattice tower located on the Champ de Mars in Paris. Built in 1889, it has become both a global icon of France and one of the most recognizable structures in the world...

while testing his invention, the coat parachuteParachuteA parachute is a device used to slow the motion of an object through an atmosphere by creating drag, or in the case of ram-air parachutes, aerodynamic lift. Parachutes are usually made out of light, strong cloth, originally silk, now most commonly nylon...

. It was his first ever attempt with the parachute and he had told the authorities in advance that he would test it first with a dummyMannequinA mannequin is an often articulated doll used by artists, tailors, dressmakers, and others especially to display or fit clothing...

. - Aurel VlaicuAurel VlaicuAurel Vlaicu was a Romanian engineer, inventor, airplane constructor and early pilot.-Biography:Aurel Vlaicu was born in Binţinţi , Geoagiu, Transylvania. He attended Calvinist High School in Orăştie and took his Baccalaureate in Sibiu in 1902...

(1882–1913) died when his self-constructed airplane, Vlaicu II, failed him during an attempt to cross the Carpathian MountainsCarpathian MountainsThe Carpathian Mountains or Carpathians are a range of mountains forming an arc roughly long across Central and Eastern Europe, making them the second-longest mountain range in Europe...

by air. - Henry Smolinski (died 1973) was killed during a test flight of the AVE MizarAVE Mizar-External links:* * * * * -See also:...

, a flying car based on the Ford PintoFord PintoThe Ford Pinto is a subcompact car produced by the Ford Motor Company for the model years 1971–1980. The car's name derives from the Pinto horse. Initially offered as a two-door sedan, Ford offered "Runabout" hatchback and wagon models the following year, competing in the U.S. market with the AMC...

and the sole product of the company he founded. - Michael Dacre (died 2009, age 53) died after testing his flying taxi device designed to accommodate fast and affordable travel among nearby cities.

Industrial

- William BullockWilliam Bullock (inventor)William Bullock was an American inventor whose 1863 invention of the web rotary printing press helped revolutionize the printing industry due to its great speed and efficiency. A few years after his invention, Bullock was accidentally killed by his own web rotary press.-Biography:William Bullock...

(1813–1867) invented the web rotary printing pressRotary printing pressA rotary printing press is a printing press in which the images to be printed are curved around a cylinder. Printing can be done on large number of substrates, including paper, cardboard, and plastic. Substrates can be sheet feed or unwound on a continuous roll through the press to be printed and...

. Several years after its invention, his foot was crushed while installing a new machine in Philadelphia. The crushed foot developed gangreneGangreneGangrene is a serious and potentially life-threatening condition that arises when a considerable mass of body tissue dies . This may occur after an injury or infection, or in people suffering from any chronic health problem affecting blood circulation. The primary cause of gangrene is reduced blood...

and Bullock died during the amputationAmputationAmputation is the removal of a body extremity by trauma, prolonged constriction, or surgery. As a surgical measure, it is used to control pain or a disease process in the affected limb, such as malignancy or gangrene. In some cases, it is carried out on individuals as a preventative surgery for...

.

Maritime

- Horace Lawson HunleyHorace Lawson HunleyHorace Lawson Hunley , was a Confederate marine engineer during the American Civil War. He developed early hand-powered submarines, the most famous of which was posthumously named for him, H. L...

(died 1863, age 40), ConfederateConfederate States of AmericaThe Confederate States of America was a government set up from 1861 to 1865 by 11 Southern slave states of the United States of America that had declared their secession from the U.S...

marine engineer and inventor of the first combat submarineSubmarineA submarine is a watercraft capable of independent operation below the surface of the water. It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability...

, CSS Hunley, died during a trial of his vessel. During a routine exercise of the submarine, which had already sunk twice previously, Hunley took command. After failing to resurface, Hunley and the seven other crew members drowned.

Medical

- Thomas Midgley, Jr.Thomas Midgley, Jr.Thomas Midgley, Jr. was an American mechanical engineer and chemist. Midgley was a key figure in a team of chemists, led by Charles F. Kettering, that developed the tetraethyllead additive to gasoline as well as some of the first chlorofluorocarbons . Over the course of his career, Midgley was...

(1889–1944) was an American engineer and chemist who contracted polio at age 51, leaving him severely disabled. He devised an elaborate system of strings and pulleys to help others lift him from bed. This system was the eventual cause of his death when he was accidentally entangled in the ropes of this device and died of strangulation at the age of 55. However, he is more famous — and infamous — for developing not only the tetraethyl lead (TEL) additive to gasolineGasolineGasoline , or petrol , is a toxic, translucent, petroleum-derived liquid that is primarily used as a fuel in internal combustion engines. It consists mostly of organic compounds obtained by the fractional distillation of petroleum, enhanced with a variety of additives. Some gasolines also contain...

, but also chlorofluorocarbonChlorofluorocarbonA chlorofluorocarbon is an organic compound that contains carbon, chlorine, and fluorine, produced as a volatile derivative of methane and ethane. A common subclass are the hydrochlorofluorocarbons , which contain hydrogen, as well. They are also commonly known by the DuPont trade name Freon...

s (CFCs).

Physics

- Marie CurieMarie CurieMarie Skłodowska-Curie was a physicist and chemist famous for her pioneering research on radioactivity. She was the first person honored with two Nobel Prizes—in physics and chemistry...

(1867–1934) invented the process to isolate radium after co-discovering the radioactive elements radiumRadiumRadium is a chemical element with atomic number 88, represented by the symbol Ra. Radium is an almost pure-white alkaline earth metal, but it readily oxidizes on exposure to air, becoming black in color. All isotopes of radium are highly radioactive, with the most stable isotope being radium-226,...

and poloniumPoloniumPolonium is a chemical element with the symbol Po and atomic number 84, discovered in 1898 by Marie Skłodowska-Curie and Pierre Curie. A rare and highly radioactive element, polonium is chemically similar to bismuth and tellurium, and it occurs in uranium ores. Polonium has been studied for...

. She died of aplastic anemiaAplastic anemiaAplastic anemia is a condition where bone marrow does not produce sufficient new cells to replenish blood cells. The condition, per its name, involves both aplasia and anemia...

as a result of prolonged exposure to ionizing radiationIonizing radiationIonizing radiation is radiation composed of particles that individually have sufficient energy to remove an electron from an atom or molecule. This ionization produces free radicals, which are atoms or molecules containing unpaired electrons...

emanating from her research materials. The dangers of radiation were not well understood at the time. - Some physicists who worked on the invention of the atom bomb at Los AlamosLos Alamos National LaboratoryLos Alamos National Laboratory is a United States Department of Energy national laboratory, managed and operated by Los Alamos National Security , located in Los Alamos, New Mexico...

died from radiation exposure, including Harry K. Daghlian, Jr.Harry K. Daghlian, Jr.Haroutune Krikor Daghlian, Jr. was an Armenian-American physicist with the Manhattan Project who accidentally irradiated himself on August 21, 1945, during a critical mass experiment at the remote Omega Site facility at Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico, resulting in his death 25 days...

(1921–1945) and Louis SlotinLouis SlotinLouis Alexander Slotin was a Canadian physicist and chemist who took part in the Manhattan Project, the secret US program during World War II that developed the atomic bomb....

(1910–1946), who both were exposed to lethal doses of radiation in separate criticality accidents involving the same sphere of plutoniumDemon coreThe Demon core was the nickname given to a subcritical mass of plutonium that accidentally went briefly critical in two separate accidents at the Los Alamos laboratory in 1945 and 1946. Each incident resulted in the acute radiation poisoning and subsequent death of a scientist...

.

Rocketry

- Max ValierMax ValierMax Valier was an Austrian rocketry pioneer. He helped found the German Verein für Raumschiffahrt that would bring together many of the minds that would later make spaceflight a reality in the 20th century.-Biography:Valier was born in Bozen , South Tyrol and in 1913 enrolled to study Physics at...

(1895–1930) invented liquid-fuelled rocket engines as a member of the 1920s German rocketeering society Verein für RaumschiffahrtVerein für RaumschiffahrtThe Verein für Raumschiffahrt was a German amateur rocket association prior to World War II that included members outside of Germany...

. On May 17, 1930, an alcohol-fuelled engine exploded on his test bench in Berlin, killing him instantly.

Punishment

- Li SiLi SiLi Si was the influential Prime Minister of the feudal state and later of the dynasty of Qin, between 246 BC and 208 BC. A famous Legalist, he was also a notable calligrapher. Li Si served under two rulers: Qin Shi Huang, king of Qin and later First Emperor of China—and his son, Qin Er Shi...

(208 BC), Prime Minister during the Qin dynastyQin DynastyThe Qin Dynasty was the first imperial dynasty of China, lasting from 221 to 207 BC. The Qin state derived its name from its heartland of Qin, in modern-day Shaanxi. The strength of the Qin state was greatly increased by the legalist reforms of Shang Yang in the 4th century BC, during the Warring...

, was executed by the Five PainsThe Five PainsThe Five Pains is a Chinese form of capital punishment invented during the Qin Dynasty . The Five Pains were as follows: first the victim's nose was cut off, followed by a hand and then a foot. The victim was then castrated and finally cut in half at the waist...

method which he had devised. - James Douglas, 4th Earl of MortonJames Douglas, 4th Earl of MortonJames Douglas, jure uxoris 4th Earl of Morton was the last of the four regents of Scotland during the minority of King James VI. He was in some ways the most successful of the four, since he did manage to win the civil war which had been dragging on with the supporters of the exiled Mary, Queen of...

(1581) was executed in Edinburgh on the Scottish MaidenMaiden (beheading)The Maiden is an early form of guillotine, or gibbet, once used as a means of execution in Edinburgh, Scotland. The Maiden is displayed at the National Museum of Scotland...

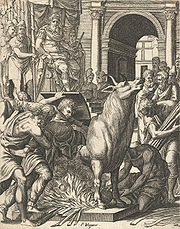

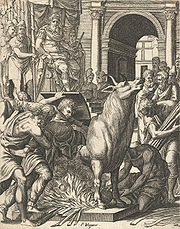

which he had introduced to Scotland as Regent. - Perillos of Athens, inventor and builder of the brazen bullBrazen bullThe brazen bull, bronze bull, or Sicilian bull, was a torture and execution device designed in ancient Greece. Its inventor, metal worker Perillos of Athens, proposed it to Phalaris, the tyrant of Akragas, Sicily, as a new means of executing criminals. The bull was made entirely of bronze, hollow,...

, was killed by his invention at the order of the tyrant PhalarisPhalarisPhalaris was the tyrant of Acragas in Sicily, from approximately 570 to 554 BC.-History:He was entrusted with the building of the temple of Zeus Atabyrius in the citadel, and took advantage of his position to make himself despot. Under his rule Agrigentum seems to have attained considerable...

, for whom the bull was built.

Railways

- Valerian AbakovskyValerian Abakovsky-Early life:Ethnically Latvian, he was born in Riga on October 5, 1895. Although a talented inventor, he worked as a chauffeur for the Tambov Cheka.-The Aerowagon:...

(1895–1921) constructed the AerowagonAerowagonThe Aerowagon or aeromotowagon was an experimental high-speed railcar fitted with an aircraft engine and propeller traction invented by Valerian Abakovsky, a Russian engineer and communist from Latvia...

, an experimental high-speed railcarRailcarA railcar, in British English and Australian English, is a self-propelled railway vehicle designed to transport passengers. The term "railcar" is usually used in reference to a train consisting of a single coach , with a driver's cab at one or both ends. Some railways, e.g., the Great Western...

fitted with an aircraft engineAircraft engineAn aircraft engine is the component of the propulsion system for an aircraft that generates mechanical power. Aircraft engines are almost always either lightweight piston engines or gas turbines...

and propeller traction; it was intended to carry Soviet officials. On July 24, 1921, a group led by Fyodor SergeyevFyodor SergeyevFyodor Andreyevich Sergeyev , better known as Comrade Artyom , was a Russian revolutionary, Soviet politician, agitator, and journalist. He was a close friend of Sergei Kirov and Stalin...

took the Aerowagon from MoscowMoscowMoscow is the capital, the most populous city, and the most populous federal subject of Russia. The city is a major political, economic, cultural, scientific, religious, financial, educational, and transportation centre of Russia and the continent...

to the TulaTula, RussiaTula is an industrial city and the administrative center of Tula Oblast, Russia. It is located south of Moscow, on the Upa River. Population: -History:...

collieries to test it, with Abakovsky also on board. They successfully arrived in Tula, but on the return route to Moscow the Aerowagon derailed at high speed, killing everyone on board, including Abakovsky (at the age of 25).

Popular myths and related stories

- Jim FixxJim FixxJames Fuller Fixx was the author of the 1977 best-selling book, The Complete Book of Running. Best known as Jim Fixx, he is credited with helping start America's fitness revolution, popularizing the sport of running and demonstrating the health benefits of regular jogging.- Life and work :Born in...

(April 23, 1932–July 20, 1984) was the author of the 19771977 in literatureThe year 1977 in literature involved some significant events and new books.-Events:*Douglas Adams begins writing for BBC radio.*V. S. Naipaul declines the offer of a CBE....

best-selling book, The Complete Book of Running. He is credited with helping start America's fitness revolution, popularizing the sport of runningRunningRunning is a means of terrestrial locomotion allowing humans and other animals to move rapidly on foot. It is simply defined in athletics terms as a gait in which at regular points during the running cycle both feet are off the ground...

and demonstrating the health benefits of regular joggingJoggingJogging is a form of trotting or running at a slow or leisurely pace. The main intention is to increase fitness with less stress on the body than from faster running.-Definition:...

. On 20 July 1984, Fixx died at the age of 52 of a fulminant heart attackMyocardial infarctionMyocardial infarction or acute myocardial infarction , commonly known as a heart attack, results from the interruption of blood supply to a part of the heart, causing heart cells to die...

, after his daily run, on Vermont Route 15 in HardwickHardwick, VermontHardwick is a town in Caledonia County, Vermont, United States. The population was 3,174 at the 2000 census.It contains the incorporated village of Hardwick and the unincorporated villages of East Hardwick and Mackville...

. - Joseph-Ignace GuillotinJoseph-Ignace GuillotinDr. Joseph-Ignace Guillotin was a French physician who proposed on 10 October 1789 the use of a device to carry out death penalties in France. While he did not invent the guillotine, and in fact opposed the death penalty, his name became an eponym for it...

(1738–1814) While he did not invent the guillotineGuillotineThe guillotine is a device used for carrying out :executions by decapitation. It consists of a tall upright frame from which an angled blade is suspended. This blade is raised with a rope and then allowed to drop, severing the head from the body...

, his name became an eponymEponymAn eponym is the name of a person or thing, whether real or fictitious, after which a particular place, tribe, era, discovery, or other item is named or thought to be named...

for it. Rumors circulated that he died by the machine, but historical references show that he died of natural causes. - Perillos of Athens (circa 550 BC), according to legend, was the first to be roasted in the brazen bullBrazen bullThe brazen bull, bronze bull, or Sicilian bull, was a torture and execution device designed in ancient Greece. Its inventor, metal worker Perillos of Athens, proposed it to Phalaris, the tyrant of Akragas, Sicily, as a new means of executing criminals. The bull was made entirely of bronze, hollow,...

he made for PhalarisPhalarisPhalaris was the tyrant of Acragas in Sicily, from approximately 570 to 554 BC.-History:He was entrusted with the building of the temple of Zeus Atabyrius in the citadel, and took advantage of his position to make himself despot. Under his rule Agrigentum seems to have attained considerable...

of Sicily for executing criminals, although he was taken out before he died. - James HeseldenJimi HeseldenJames William "Jimi" Heselden OBE was a British entrepreneur. A former coal miner, Heselden made his fortune manufacturing the Hesco bastion barrier system. In 2010, he bought Segway Inc., maker of the Segway personal transport system. Heselden died in 2010 from injuries apparently sustained...

(1948–2010), owner of the SegwaySegway Inc.Segway Inc. of New Hampshire, USA is the manufacturer of a two-wheeled, self-balancing electric vehicle, the Segway PT, invented by Dean Kamen...

production company, died in a Segway accident. Dean KamenDean KamenDean L. Kamen is an American entrepreneur and inventor from New Hampshire.Born in Rockville Centre, New York, he attended Worcester Polytechnic Institute, but dropped out before graduating after five years of private advanced research for drug infusion pump AutoSyringe...

invented the SegwaySegway PTThe Segway PT is a two-wheeled, self-balancing transportation machine invented by Dean Kamen. It is produced by Segway Inc. of New Hampshire, USA. The name "Segway" is a homophone of "segue" while "PT" denotes personal transporter....

. - Wan HuWan HuAccording to legend, Wàn Hǔ was a minor Chinese official of the Ming dynasty who attempted to become the world's first recorded "astronaut". The crater Wan-Hoo on the far side of the Moon is named after him.-The Legend of Wan Hu:...

, a sixteenth-century Chinese official, is said to have attempted to launch himself into outer space in a chair to which 47 rockets were attached. The rockets exploded and, it is said, neither he nor the chair were ever seen again.