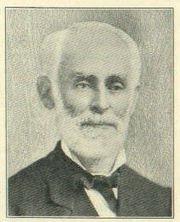

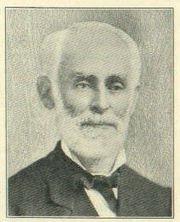

John W. Johnston

Encyclopedia

John Warfield Johnston was an American lawyer and politician from Abingdon, Virginia

. He served in the Virginia State Senate

, and represented Virginia

in the United States Senate

when the state was readmitted after the American Civil War

. He was United States Senator for thirteen years; in national politics, he was a Democrat

.

Johnston had been ineligible to serve in Congress because of the Fourteenth Amendment, which forbade anyone from holding public office who had sworn allegiance to the United States and subsequently sided with the Confederacy during the Civil War. However, his restrictions were removed at the suggestion of the Freedman's Bureau when he aided a sick and dying former slave after the War. He was the first person who had sided with the Confederacy to serve in the United States Senate.

Several issues marked Johnston's senatorial career. He was caught in the middle during the debate over the Arlington Memorial

. The initial proposal to relocate the dead was distasteful to Johnston, yet the ensuing debate caused him to want to defend the memory of Robert E. Lee

; the need to stay quiet for the sake of the Democratic Party, however, proved decisive. Johnston was an outspoken opponent of the Texas-Pacific Bill, a sectional struggle for control of railroads in the South, which figured in the Compromise of 1877

. He was also an outspoken Funder during Virginia's heated debate as to how much of its pre-War debt the state ought to have been obliged to pay back. The controversy culminated in the formation of Readjuster Party

and the appointment of William Mahone

as its leader; this marked the end of Johnston's career in the Senate.

, on September 9, 1818. He was the only child of Dr. John Warfield Johnston and Louisa Smith Bowen. His grandfather was Judge Peter Johnston, who had fought under Henry "Light Horse" Harry Lee during the Revolutionary War

, and his great-grandmother was the sister of Patrick Henry

. His mother was the sister of Rees T. Bowen, a Virginia politician, and his paternal uncles included Charles Clement Johnston

and General Joseph Eggleston Johnston. His first cousin was U. S. Congressman Henry Bowen

. Johnston's ancestry was Scottish

, English

, Welsh

, and Scots-Irish

.

Johnston attended Abingdon Academy, South Carolina College at Columbia, and the law department of the University of Virginia at Charlottesville. He was admitted to the bar in 1839 and commenced practice in Tazewell

, Tazewell County, Virginia

.

On October 12, 1841, he married Nicketti Buchanan Floyd, the daughter of Governor John Floyd

and Letitia Preston, and the sister of Governor John Buchanan Floyd. His wife was Catholic, having converted when young; Johnston converted after the marriage.

In 1859, he moved his family to Abingdon, Virginia

, and lived at first on East Main Street. An Abingdon resident noted that "it was a delightful home to visit and the young men enjoyed the cordial welcome that they received from the old and the young." While there, the family started construction of a new home called "Eggleston", three miles (5 km) east of town; the family's affectionate name for it was "Castle Dusty". They moved in sometime after August 1860.

Johnston and Nicketti Buchanan Floyd had twelve children, one of whom was Dr. George Ben Johnston, prominent physician in Richmond who is credited with the first antiseptic operation performed in Virginia. Both the Johnston Memorial Hospital in Abingdon and the Johnston-Willis Hospital in Richmond

are named after him.

Johnston served as commonwealth attorney

Johnston served as commonwealth attorney

for Tazewell County between 1844 and 1846. In 1846, he was elected to serve the remainder of the 1846–1847 term in the Virginia Senate, representing Tazewell, Wythe, Grayson, Smyth, Carroll, and Pulaski counties. He was re-elected for the 1847–1848 session.

During the Civil War, he held the position of Confederate States receiver, and was also elected as a councilman for the town of Abingdon in 1861. Not much is known of his activities during the war, but he did send a letter to Brigadier-General John Echols that the Order of Heroes of America, was "growing fearfully" in southwest Virginia. This secret order was composed of Union sympathizers. This information was used in conjunction with other reports to request a suspension of habeas corpus so that the military could make arrests.

After the war, in 1867, he founded the Villa Maria Academy of the Visitation in Abingdon for the education of girls. He was judge of the Circuit Superior Court

of Law and Chancery of Virginia in 1869–1870. Also around 1869, he formed a law partnership with a young local attorney, and his future son-in-law, Daniel Trigg. In 1872, they set up their offices in a small building near the courthouse which became known as the Johnston-Trigg Law Office.

In November 1868, he wrote a letter to his daughter, which revealed that butter was scarce and that he doubted he would get a supply for the winter, but that "when we have spare ribs, sausages & crackilin bread, we can do without butter. The fact is I begin to consider butter a luxury anyhow, that poor people have no business with."

roots. The new General Assembly ratified the Fourteenth

and Fifteenth Amendments

to end Reconstruction and also elected two people as representatives for the U. S. Senate, including Johnston. He was to serve the unexpired portion of a six-year term that started in March 1865. Johnston received a letter from William Mahone

, sent on October 18, 1869, that he must go to Richmond "without fail, by the first train. You are Senator."

Johnston was one of the few Virginia men eligible to hold office: at the time, anyone who had fought for, or served, the former Confederacy was ineligible to hold office under the Fourteenth Amendment until their "political disabilities" were removed by Congress by a two-thirds vote. Johnston's were removed because word had reached the local Abingdon Freedman's Bureau officer that he had helped care for an elderly former slave, Peter, who had passed through Abingdon on his way to Charlotte County, Virginia

from Mississippi

.

The Norfolk and Western Railroad passed 200 yards (182.9 m) from Johnston's house, and former slaves used the tracks as a guide to return home from where they had been sold. In the summer of 1865 Johnston aided many with food and shelter, and in August of that year he found Peter near death in a stable near the railroad; Johnston carried him to the house, where he stayed at least a month.

When Peter regained enough strength he told his story, which Johnston later wrote down and is now kept with his papers at Duke University

. Peter had been a slave of a Mr. Read in Charlotte County, a neighbor of John Randolph

. He had been sold (apparently because of Read's debts) to a trader, leaving behind a wife and young daughter to work a cotton field for thirty-five years in Mississippi. When he was freed, Peter walked from Mississippi until he reached Abingdon in his quest to return home. Johnston wrote: "It was evident to me and my wife that all our care could not rebuild that worn-out body, and that death was near at hand. He weakened rapidly ... His life was weary, toilsome, and full of trouble. But surely the Lord has rewards for such as he, and will give him rest in all eternity, and permit him to see Susy and his Mammy and Daddy." Peter died of tuberculosis.

The Freedman's Bureau agent wrote to Congressman William Kelly

of Pennsylvania requesting the removal of Johnston's disabilities because of his charity. Kelly did so and the bill passed both houses of Congress. Johnston only discovered all of this when he read about the passage of the bill in the newspaper.

When Johnston arrived on January 28 to take his seat, he had some difficulty. George F. Edmunds

of Vermont

questioned whether he was the right Mr. Johnston and thought a fraud was being perpetrated until Waitman T. Willey

of West Virginia vouched for Johnston's identity, allowing his qualification. Later, he was in the process of signing a document put before him, but without having read it. This was the ironclad oath

, that required all white males to swear they had never borne arms against the Union or supported the Confederacy. If the senator sitting next to Johnston, Thomas F. Bayard

of Delaware

, had not noticed, Johnston would likely have been "disgraced ... forever in the eyes of the people of Virginia ..." The oath had been deemed unconstitutional in 1867, but its use was not effectively ended until 1871. At this time, Johnston was the only senator who had sided with the Confederacy—all the rest were either Northerners by birth or had been "Union men".

At the time he joined the Senate, the two parties in Virginia were the Conservatives and the Radicals. Johnston was a Conservative, which was an alliance of pre-War Democrats and Whigs

. The Democrats had once been bitter rivals of the Whigs and would not join a party of that name, giving rise to the Conservative party. Which direction Johnston would vote in the national arena was unknown, but mattered little because the Senate was overwhelmingly Republican. There were only 10 Democrats at the time out of 68 senators. There was speculation that Johnston might side with the Republicans and "turn traitor to his party and state ... for patronage" based on a letter he had written to the new Virginia governor. These doubts were settled when Johnston declined a formal invitation to join the Republican caucus and went to a joint meeting of House and Senate Democrats; it was declared that "a Conservative in Virginia was a democrat in Washington."

Johnston served from January 26, 1870, to March 4, 1871, and was re-elected on March 15, 1871, for the term beginning March 4, 1871. He was re-elected again in 1877 and served until March 4, 1883. He was a member Committee on Revolutionary Claims, and later served as its chairman during the Forty-fifth

and Forty-seventh Congresses

. He was also chairman of the Committee on Agriculture during the Forty-sixth Congress

.

In November 1881, Johnston served on the Committee on Foreign Relations. It is recorded that when Clara Barton

's plea to President Chester Arthur to sign the First Geneva Convention

(establishing the International Red Cross), Arthur's favorable reply was referred to this committee and Johnston was named as one of the members.

On December 13, 1870, Thomas C. McCreery

On December 13, 1870, Thomas C. McCreery

(D) of Kentucky

introduced a resolution regarding the Arlington House

, the former home of Robert E. Lee

, that brought down a firestorm of objections. The resolution called for an investigation to establish its ownership and the possibility of returning it to Mrs. Robert E. Lee

. In addition, McCreery proposed the government fix up the premises, return any Washington

relics discovered, and determine whether a suitable location nearby existed to relocate the dead. Johnston described the excitement caused as the most pronounced he would see in his thirteen years in the Senate. It put him in "the most painful and embarrassing position of my life". and he was vehemently opposed:

However, in the course of the speeches opposing the resolution, Johnston felt General Lee

's memory had been attacked and he felt duty bound to defend him. The Democratic Party, knowing his views and that of his state, approached him and asked him to keep silent for the sake of the party and the relief of Virginia. Johnston correctly predicted that he would be attacked at home. He was up for re-election, and the opposing candidates used his position against him. A delegation from the Virginia General Assembly

travelled to Washington to talk with the Democrats and assess the situation and were satisfied by the reports they received.

Later, Johnston made a speech on behalf of Mrs. Lee and her Memorial proposal. His first attempt to speak was objected to and he was denied permission. Near the end of the session, when an unrelated bill was under discussion, Johnston made a motion related to it and then used the opportunity, which was allowed to Senators, to make his speech; this caused "great indignation and impatience on the floor". The Lee family and their advisors desired that the "true facts about the sale of Arlington and the nature of her claim to the property, should be placed before the country" so that, if found in her favor, she could receive compensation and then donate the property to the government. Eventually the Supreme Court of the United States

did find in the family's favor in 1882.

When Johnston was up for re-election in 1877, he was involved in the controversial Texas-Pacific Bill, a battle between Northern and Southern railroad interests. Johnston was opposed to Tom Scott's Texas and Pacific Railway

When Johnston was up for re-election in 1877, he was involved in the controversial Texas-Pacific Bill, a battle between Northern and Southern railroad interests. Johnston was opposed to Tom Scott's Texas and Pacific Railway

, and the bill, which favored Scott's interests. Scott was trying to persuade Southern states to accept his railroad so that they would subsequently appoint senators who would vote for the bill. Johnston's seat was vulnerable if Scott succeeded in influencing the Virginia legislature, as it was known that he opposed the bill. As Johnston wrote in a letter, "...what I have done about the Pacific road is before the people and I cannot recall it if I would. It would not be policy to retreat from my position nor am I inclined to do so, if was policy. I thought & I think that I was right & am therefore ready to take the consequences. I intend to fight it out on that line." William Mahone worked to prevent his re-election. Most Southern states went along with Scott, but Virginia and Louisiana did not, and Johnston was re-elected.

The Texas-Pacific Bill remained a bargaining chip in the Compromise of 1877

, following the 1876 Presidential election crisis. Later, Johnston gave a speech in 1878 in Congress against the railroad, specifically Bill No. 942, which he viewed as "a positive menace to the commercial interests of the South."

and the Democratic Party

. William Mahone was chosen as head of the Readjusters and they gained control of the state legislature in 1879, but not the governorship. The legislature then elected Mahone as the successor to Democrat Robert E. Withers

in the U. S. Senate. However, without a sympathetic governor, they could not enact their reforms. Their next chance came in the election of 1881; their aim was to elect a governor, but most importantly to maintain control of the state legislature, since it would elect "a successor to the Hon. John W. Johnston..." Their party succeeded and the legislature elected prominent Readjuster, and Mahone's "intimate friend", Harrison H. Riddleberger

to replace Johnston, eighty-one to forty-nine.

, on February 27, 1889, aged seventy. He was conscious until his death and was aware that he was dying. On March 1, his family brought his body from Richmond to Wytheville, where he was buried in St. Mary's Cemetery.

On May 11, 1903, a ceremony was held to install the portraits of deceased judges in the Washington County Courthouse. David F. Bailey was the speaker that presented the portrait of Johnston. In his speech, he described Johnston:

Johnston was outlived by his wife, Nicketti, who died on June 9, 1908, aged eighty-nine.

Abingdon, Virginia

Abingdon is a town in Washington County, Virginia, USA, 133 miles southwest of Roanoke. The population was 8,191 at the 2010 census. It is the county seat of Washington County and is a designated Virginia Historic Landmark...

. He served in the Virginia State Senate

Senate of Virginia

The Senate of Virginia is the upper house of the Virginia General Assembly. The Senate is composed of 40 Senators representing an equal number of single-member constituent districts. The Senate is presided over by the Lieutenant Governor of Virginia...

, and represented Virginia

Virginia

The Commonwealth of Virginia , is a U.S. state on the Atlantic Coast of the Southern United States. Virginia is nicknamed the "Old Dominion" and sometimes the "Mother of Presidents" after the eight U.S. presidents born there...

in the United States Senate

United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper house of the bicameral legislature of the United States, and together with the United States House of Representatives comprises the United States Congress. The composition and powers of the Senate are established in Article One of the U.S. Constitution. Each...

when the state was readmitted after the American Civil War

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

. He was United States Senator for thirteen years; in national politics, he was a Democrat

Democratic Party (United States)

The Democratic Party is one of two major contemporary political parties in the United States, along with the Republican Party. The party's socially liberal and progressive platform is largely considered center-left in the U.S. political spectrum. The party has the lengthiest record of continuous...

.

Johnston had been ineligible to serve in Congress because of the Fourteenth Amendment, which forbade anyone from holding public office who had sworn allegiance to the United States and subsequently sided with the Confederacy during the Civil War. However, his restrictions were removed at the suggestion of the Freedman's Bureau when he aided a sick and dying former slave after the War. He was the first person who had sided with the Confederacy to serve in the United States Senate.

Several issues marked Johnston's senatorial career. He was caught in the middle during the debate over the Arlington Memorial

Arlington House, The Robert E. Lee Memorial

Arlington House, The Robert E. Lee Memorial, formerly named the Custis-Lee Mansion, is a Greek revival style mansion located in Arlington, Virginia, USA that was once the home of Confederate General Robert E. Lee. It overlooks the Potomac River, directly across from the National Mall in Washington,...

. The initial proposal to relocate the dead was distasteful to Johnston, yet the ensuing debate caused him to want to defend the memory of Robert E. Lee

Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee was a career military officer who is best known for having commanded the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia in the American Civil War....

; the need to stay quiet for the sake of the Democratic Party, however, proved decisive. Johnston was an outspoken opponent of the Texas-Pacific Bill, a sectional struggle for control of railroads in the South, which figured in the Compromise of 1877

Compromise of 1877

The Compromise of 1877, also known as the Corrupt Bargain, refers to a purported informal, unwritten deal that settled the disputed 1876 U.S. Presidential election and ended Congressional Reconstruction. Through it, Republican Rutherford B. Hayes was awarded the White House over Democrat Samuel J...

. He was also an outspoken Funder during Virginia's heated debate as to how much of its pre-War debt the state ought to have been obliged to pay back. The controversy culminated in the formation of Readjuster Party

Readjuster Party

The Readjuster Party was a political coalition formed in Virginia in the late 1870s during the turbulent period following the American Civil War. Readjusters aspired "to break the power of wealth and established privilege" and to promote public education, a program which attracted biracial support....

and the appointment of William Mahone

William Mahone

William Mahone was a civil engineer, teacher, soldier, railroad executive, and a member of the Virginia General Assembly and U.S. Congress. Small of stature, he was nicknamed "Little Billy"....

as its leader; this marked the end of Johnston's career in the Senate.

Family and early life

Johnston was born in his paternal grandfather's house, "Panicello", near Abingdon, VirginiaAbingdon, Virginia

Abingdon is a town in Washington County, Virginia, USA, 133 miles southwest of Roanoke. The population was 8,191 at the 2010 census. It is the county seat of Washington County and is a designated Virginia Historic Landmark...

, on September 9, 1818. He was the only child of Dr. John Warfield Johnston and Louisa Smith Bowen. His grandfather was Judge Peter Johnston, who had fought under Henry "Light Horse" Harry Lee during the Revolutionary War

American Revolution

The American Revolution was the political upheaval during the last half of the 18th century in which thirteen colonies in North America joined together to break free from the British Empire, combining to become the United States of America...

, and his great-grandmother was the sister of Patrick Henry

Patrick Henry

Patrick Henry was an orator and politician who led the movement for independence in Virginia in the 1770s. A Founding Father, he served as the first and sixth post-colonial Governor of Virginia from 1776 to 1779 and subsequently, from 1784 to 1786...

. His mother was the sister of Rees T. Bowen, a Virginia politician, and his paternal uncles included Charles Clement Johnston

Charles Clement Johnston

Charles Clement Johnston was a U.S. Representative from Virginia.Born in Prince Edward County, Virginia, and educated at home, he moved with his parents to Panicello, near Abingdon, Virginia, in 1811. He studied law and was admitted to the bar in 1818 and commenced practice in Abingdon, Virginia...

and General Joseph Eggleston Johnston. His first cousin was U. S. Congressman Henry Bowen

Henry Bowen

Henry Bowen was a Virginia lawyer and politician from Tazewell County, Virginia. He served in the Virginia House of Delegates, as well as the U.S. House of Representatives.- Family and early life :...

. Johnston's ancestry was Scottish

Scottish people

The Scottish people , or Scots, are a nation and ethnic group native to Scotland. Historically they emerged from an amalgamation of the Picts and Gaels, incorporating neighbouring Britons to the south as well as invading Germanic peoples such as the Anglo-Saxons and the Norse.In modern use,...

, English

English people

The English are a nation and ethnic group native to England, who speak English. The English identity is of early mediaeval origin, when they were known in Old English as the Anglecynn. England is now a country of the United Kingdom, and the majority of English people in England are British Citizens...

, Welsh

Welsh people

The Welsh people are an ethnic group and nation associated with Wales and the Welsh language.John Davies argues that the origin of the "Welsh nation" can be traced to the late 4th and early 5th centuries, following the Roman departure from Britain, although Brythonic Celtic languages seem to have...

, and Scots-Irish

Scots-Irish American

Scotch-Irish Americans are an estimated 250,000 Presbyterian and other Protestant dissenters from the Irish province of Ulster who immigrated to North America primarily during the colonial era and their descendants. Some scholars also include the 150,000 Ulster Protestants who immigrated to...

.

Johnston attended Abingdon Academy, South Carolina College at Columbia, and the law department of the University of Virginia at Charlottesville. He was admitted to the bar in 1839 and commenced practice in Tazewell

Tazewell, Virginia

Tazewell is a town in Tazewell County, Virginia, USA. The population was 4,206 at the 2000 census. It is part of the Bluefield, WV-VA micropolitan area, which has a population of 107,578. It is the county seat of Tazewell County....

, Tazewell County, Virginia

Tazewell County, Virginia

As of the census of 2000, there were 44,598 people, 18,277 households and 13,232 families residing in the county. The population density was 86 people per square mile . There were 20,390 housing units at an average density of 39 per square mile...

.

On October 12, 1841, he married Nicketti Buchanan Floyd, the daughter of Governor John Floyd

John Floyd (Virginia politician)

John Floyd was a Virginia politician and soldier. He represented Virginia in the United States House of Representatives and later served as the 25th Governor of Virginia....

and Letitia Preston, and the sister of Governor John Buchanan Floyd. His wife was Catholic, having converted when young; Johnston converted after the marriage.

In 1859, he moved his family to Abingdon, Virginia

Abingdon, Virginia

Abingdon is a town in Washington County, Virginia, USA, 133 miles southwest of Roanoke. The population was 8,191 at the 2010 census. It is the county seat of Washington County and is a designated Virginia Historic Landmark...

, and lived at first on East Main Street. An Abingdon resident noted that "it was a delightful home to visit and the young men enjoyed the cordial welcome that they received from the old and the young." While there, the family started construction of a new home called "Eggleston", three miles (5 km) east of town; the family's affectionate name for it was "Castle Dusty". They moved in sometime after August 1860.

Johnston and Nicketti Buchanan Floyd had twelve children, one of whom was Dr. George Ben Johnston, prominent physician in Richmond who is credited with the first antiseptic operation performed in Virginia. Both the Johnston Memorial Hospital in Abingdon and the Johnston-Willis Hospital in Richmond

Richmond, Virginia

Richmond is the capital of the Commonwealth of Virginia, in the United States. It is an independent city and not part of any county. Richmond is the center of the Richmond Metropolitan Statistical Area and the Greater Richmond area...

are named after him.

Early career

State's Attorney

In the United States, the State's Attorney is, most commonly, an elected official who represents the State in criminal prosecutions and is often the chief law enforcement officer of their respective county, circuit...

for Tazewell County between 1844 and 1846. In 1846, he was elected to serve the remainder of the 1846–1847 term in the Virginia Senate, representing Tazewell, Wythe, Grayson, Smyth, Carroll, and Pulaski counties. He was re-elected for the 1847–1848 session.

During the Civil War, he held the position of Confederate States receiver, and was also elected as a councilman for the town of Abingdon in 1861. Not much is known of his activities during the war, but he did send a letter to Brigadier-General John Echols that the Order of Heroes of America, was "growing fearfully" in southwest Virginia. This secret order was composed of Union sympathizers. This information was used in conjunction with other reports to request a suspension of habeas corpus so that the military could make arrests.

After the war, in 1867, he founded the Villa Maria Academy of the Visitation in Abingdon for the education of girls. He was judge of the Circuit Superior Court

Circuit court

Circuit court is the name of court systems in several common law jurisdictions.-History:King Henry II instituted the custom of having judges ride around the countryside each year to hear appeals, rather than forcing everyone to bring their appeals to London...

of Law and Chancery of Virginia in 1869–1870. Also around 1869, he formed a law partnership with a young local attorney, and his future son-in-law, Daniel Trigg. In 1872, they set up their offices in a small building near the courthouse which became known as the Johnston-Trigg Law Office.

In November 1868, he wrote a letter to his daughter, which revealed that butter was scarce and that he doubted he would get a supply for the winter, but that "when we have spare ribs, sausages & crackilin bread, we can do without butter. The fact is I begin to consider butter a luxury anyhow, that poor people have no business with."

Initial restrictions

In 1869, modern-day Virginia was essentially a military zone. Gilbert C. Walker was elected as governor in this year and ushered in a moderate conservatism, with WhiggishWhig Party (United States)

The Whig Party was a political party of the United States during the era of Jacksonian democracy. Considered integral to the Second Party System and operating from the early 1830s to the mid-1850s, the party was formed in opposition to the policies of President Andrew Jackson and his Democratic...

roots. The new General Assembly ratified the Fourteenth

Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution was adopted on July 9, 1868, as one of the Reconstruction Amendments.Its Citizenship Clause provides a broad definition of citizenship that overruled the Dred Scott v...

and Fifteenth Amendments

Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution prohibits each government in the United States from denying a citizen the right to vote based on that citizen's "race, color, or previous condition of servitude"...

to end Reconstruction and also elected two people as representatives for the U. S. Senate, including Johnston. He was to serve the unexpired portion of a six-year term that started in March 1865. Johnston received a letter from William Mahone

William Mahone

William Mahone was a civil engineer, teacher, soldier, railroad executive, and a member of the Virginia General Assembly and U.S. Congress. Small of stature, he was nicknamed "Little Billy"....

, sent on October 18, 1869, that he must go to Richmond "without fail, by the first train. You are Senator."

Johnston was one of the few Virginia men eligible to hold office: at the time, anyone who had fought for, or served, the former Confederacy was ineligible to hold office under the Fourteenth Amendment until their "political disabilities" were removed by Congress by a two-thirds vote. Johnston's were removed because word had reached the local Abingdon Freedman's Bureau officer that he had helped care for an elderly former slave, Peter, who had passed through Abingdon on his way to Charlotte County, Virginia

Charlotte County, Virginia

As of the census of 2000, there were 12,472 people, 4,951 households, and 3,435 families residing in the county. The population density was 26 people per square mile . There were 5,734 housing units at an average density of 12 per square mile...

from Mississippi

Mississippi

Mississippi is a U.S. state located in the Southern United States. Jackson is the state capital and largest city. The name of the state derives from the Mississippi River, which flows along its western boundary, whose name comes from the Ojibwe word misi-ziibi...

.

The Norfolk and Western Railroad passed 200 yards (182.9 m) from Johnston's house, and former slaves used the tracks as a guide to return home from where they had been sold. In the summer of 1865 Johnston aided many with food and shelter, and in August of that year he found Peter near death in a stable near the railroad; Johnston carried him to the house, where he stayed at least a month.

When Peter regained enough strength he told his story, which Johnston later wrote down and is now kept with his papers at Duke University

Duke University

Duke University is a private research university located in Durham, North Carolina, United States. Founded by Methodists and Quakers in the present day town of Trinity in 1838, the school moved to Durham in 1892. In 1924, tobacco industrialist James B...

. Peter had been a slave of a Mr. Read in Charlotte County, a neighbor of John Randolph

John Randolph of Roanoke

John Randolph , known as John Randolph of Roanoke, was a planter and a Congressman from Virginia, serving in the House of Representatives , the Senate , and also as Minister to Russia...

. He had been sold (apparently because of Read's debts) to a trader, leaving behind a wife and young daughter to work a cotton field for thirty-five years in Mississippi. When he was freed, Peter walked from Mississippi until he reached Abingdon in his quest to return home. Johnston wrote: "It was evident to me and my wife that all our care could not rebuild that worn-out body, and that death was near at hand. He weakened rapidly ... His life was weary, toilsome, and full of trouble. But surely the Lord has rewards for such as he, and will give him rest in all eternity, and permit him to see Susy and his Mammy and Daddy." Peter died of tuberculosis.

The Freedman's Bureau agent wrote to Congressman William Kelly

William Kelly

William Kelly or Bill Kelly may refer to:*Bill Kelly , American football player at the University of Montana and in the NFL*Bill Kelly , American football player and coach...

of Pennsylvania requesting the removal of Johnston's disabilities because of his charity. Kelly did so and the bill passed both houses of Congress. Johnston only discovered all of this when he read about the passage of the bill in the newspaper.

Overview

Johnston went to Washington in December in hopes that Virginia would be readmitted to the Union. It was, however, not until January 26, 1870, that Virginia was readmitted; Johnston was able to take his seat shortly afterward. The delay was due to a Congressional need to pass an act that would allow Virginia representation in the body.When Johnston arrived on January 28 to take his seat, he had some difficulty. George F. Edmunds

George F. Edmunds

George Franklin Edmunds was a Republican U.S. Senator from Vermont from 1866 to 1891.Born in Richmond, Vermont, Edmunds attended common schools and was privately tutored as a child. After being admitted to the bar in 1849, he started a law practice in Burlington, Vermont...

of Vermont

Vermont

Vermont is a state in the New England region of the northeastern United States of America. The state ranks 43rd in land area, , and 45th in total area. Its population according to the 2010 census, 630,337, is the second smallest in the country, larger only than Wyoming. It is the only New England...

questioned whether he was the right Mr. Johnston and thought a fraud was being perpetrated until Waitman T. Willey

Waitman T. Willey

Waitman Thomas Willey was an American lawyer and politician from Morgantown, West Virginia. He represented both the states of Virginia and West Virginia in the United States Senate and was one of West Virginia's first two Senators.Willey was born in 1811, in a log cabin near the present day...

of West Virginia vouched for Johnston's identity, allowing his qualification. Later, he was in the process of signing a document put before him, but without having read it. This was the ironclad oath

Ironclad oath

The Ironclad Oath was a key factor in the removing of ex-Confederates from the political arena during the Reconstruction of the United States in the 1860s...

, that required all white males to swear they had never borne arms against the Union or supported the Confederacy. If the senator sitting next to Johnston, Thomas F. Bayard

Thomas F. Bayard

Thomas Francis Bayard was an American lawyer and politician from Wilmington, Delaware. He was a member of the Democratic Party, who served three terms as U.S. Senator from Delaware, and as U.S. Secretary of State, and U.S. Ambassador to the United Kingdom.-Early life and family:Bayard was born in...

of Delaware

Delaware

Delaware is a U.S. state located on the Atlantic Coast in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It is bordered to the south and west by Maryland, and to the north by Pennsylvania...

, had not noticed, Johnston would likely have been "disgraced ... forever in the eyes of the people of Virginia ..." The oath had been deemed unconstitutional in 1867, but its use was not effectively ended until 1871. At this time, Johnston was the only senator who had sided with the Confederacy—all the rest were either Northerners by birth or had been "Union men".

At the time he joined the Senate, the two parties in Virginia were the Conservatives and the Radicals. Johnston was a Conservative, which was an alliance of pre-War Democrats and Whigs

Whig Party (United States)

The Whig Party was a political party of the United States during the era of Jacksonian democracy. Considered integral to the Second Party System and operating from the early 1830s to the mid-1850s, the party was formed in opposition to the policies of President Andrew Jackson and his Democratic...

. The Democrats had once been bitter rivals of the Whigs and would not join a party of that name, giving rise to the Conservative party. Which direction Johnston would vote in the national arena was unknown, but mattered little because the Senate was overwhelmingly Republican. There were only 10 Democrats at the time out of 68 senators. There was speculation that Johnston might side with the Republicans and "turn traitor to his party and state ... for patronage" based on a letter he had written to the new Virginia governor. These doubts were settled when Johnston declined a formal invitation to join the Republican caucus and went to a joint meeting of House and Senate Democrats; it was declared that "a Conservative in Virginia was a democrat in Washington."

Johnston served from January 26, 1870, to March 4, 1871, and was re-elected on March 15, 1871, for the term beginning March 4, 1871. He was re-elected again in 1877 and served until March 4, 1883. He was a member Committee on Revolutionary Claims, and later served as its chairman during the Forty-fifth

45th United States Congress

-House of Representatives:-Leadership:-Senate:*President: William A. Wheeler *President pro tempore: Thomas W. Ferry -House of Representatives:*Speaker: Samuel J. Randall -Members:This list is arranged by chamber, then by state...

and Forty-seventh Congresses

47th United States Congress

The Forty-seventh United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C. from March 4, 1881 to March 4, 1883, during the administration...

. He was also chairman of the Committee on Agriculture during the Forty-sixth Congress

46th United States Congress

The Forty-sixth United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C. from March 4, 1879 to March 4, 1881, during the last two years of...

.

In November 1881, Johnston served on the Committee on Foreign Relations. It is recorded that when Clara Barton

Clara Barton

Clarissa Harlowe "Clara" Barton was a pioneer American teacher, patent clerk, nurse, and humanitarian. She is best remembered for organizing the American Red Cross.-Youth, education, and family nursing:...

's plea to President Chester Arthur to sign the First Geneva Convention

First Geneva Convention

The First Geneva Convention, for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded in Armies in the Field, is one of four treaties of the Geneva Conventions. It defines "the basis on which rest the rules of international law for the protection of the victims of armed conflicts." It was first adopted...

(establishing the International Red Cross), Arthur's favorable reply was referred to this committee and Johnston was named as one of the members.

Arlington Memorial controversy

Thomas C. McCreery

Thomas Clay McCreery was a Democratic U.S. Senator from Kentucky.Born at Yelvington, Kentucky., McCreery graduated from Centre College, in Danville, Kentucky, in 1837. He studied law, passed the bar, and commenced practice in Frankfort, Kentucky...

(D) of Kentucky

Kentucky

The Commonwealth of Kentucky is a state located in the East Central United States of America. As classified by the United States Census Bureau, Kentucky is a Southern state, more specifically in the East South Central region. Kentucky is one of four U.S. states constituted as a commonwealth...

introduced a resolution regarding the Arlington House

Arlington House, The Robert E. Lee Memorial

Arlington House, The Robert E. Lee Memorial, formerly named the Custis-Lee Mansion, is a Greek revival style mansion located in Arlington, Virginia, USA that was once the home of Confederate General Robert E. Lee. It overlooks the Potomac River, directly across from the National Mall in Washington,...

, the former home of Robert E. Lee

Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee was a career military officer who is best known for having commanded the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia in the American Civil War....

, that brought down a firestorm of objections. The resolution called for an investigation to establish its ownership and the possibility of returning it to Mrs. Robert E. Lee

Mary Anna Custis Lee

Mary Anna Randolph Custis Lee was the wife of Confederate General Robert E. Lee.-Biography:Mary Anna Custis Lee was the only surviving child of George Washington Parke Custis, George Washington's step-grandson and adopted son and founder of Arlington House, and Mary Lee Fitzhugh Custis, daughter...

. In addition, McCreery proposed the government fix up the premises, return any Washington

George Washington

George Washington was the dominant military and political leader of the new United States of America from 1775 to 1799. He led the American victory over Great Britain in the American Revolutionary War as commander-in-chief of the Continental Army from 1775 to 1783, and presided over the writing of...

relics discovered, and determine whether a suitable location nearby existed to relocate the dead. Johnston described the excitement caused as the most pronounced he would see in his thirteen years in the Senate. It put him in "the most painful and embarrassing position of my life". and he was vehemently opposed:

However, in the course of the speeches opposing the resolution, Johnston felt General Lee

Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee was a career military officer who is best known for having commanded the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia in the American Civil War....

's memory had been attacked and he felt duty bound to defend him. The Democratic Party, knowing his views and that of his state, approached him and asked him to keep silent for the sake of the party and the relief of Virginia. Johnston correctly predicted that he would be attacked at home. He was up for re-election, and the opposing candidates used his position against him. A delegation from the Virginia General Assembly

Virginia General Assembly

The Virginia General Assembly is the legislative body of the Commonwealth of Virginia, and the oldest legislative body in the Western Hemisphere, established on July 30, 1619. The General Assembly is a bicameral body consisting of a lower house, the Virginia House of Delegates, with 100 members,...

travelled to Washington to talk with the Democrats and assess the situation and were satisfied by the reports they received.

Later, Johnston made a speech on behalf of Mrs. Lee and her Memorial proposal. His first attempt to speak was objected to and he was denied permission. Near the end of the session, when an unrelated bill was under discussion, Johnston made a motion related to it and then used the opportunity, which was allowed to Senators, to make his speech; this caused "great indignation and impatience on the floor". The Lee family and their advisors desired that the "true facts about the sale of Arlington and the nature of her claim to the property, should be placed before the country" so that, if found in her favor, she could receive compensation and then donate the property to the government. Eventually the Supreme Court of the United States

Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States is the highest court in the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all state and federal courts, and original jurisdiction over a small range of cases...

did find in the family's favor in 1882.

Texas-Pacific Bill

Texas and Pacific Railway

The Texas and Pacific Railway Company was created by federal charter in 1871 with the purpose of building a southern transcontinental railroad between Marshall, Texas, and San Diego, California....

, and the bill, which favored Scott's interests. Scott was trying to persuade Southern states to accept his railroad so that they would subsequently appoint senators who would vote for the bill. Johnston's seat was vulnerable if Scott succeeded in influencing the Virginia legislature, as it was known that he opposed the bill. As Johnston wrote in a letter, "...what I have done about the Pacific road is before the people and I cannot recall it if I would. It would not be policy to retreat from my position nor am I inclined to do so, if was policy. I thought & I think that I was right & am therefore ready to take the consequences. I intend to fight it out on that line." William Mahone worked to prevent his re-election. Most Southern states went along with Scott, but Virginia and Louisiana did not, and Johnston was re-elected.

The Texas-Pacific Bill remained a bargaining chip in the Compromise of 1877

Compromise of 1877

The Compromise of 1877, also known as the Corrupt Bargain, refers to a purported informal, unwritten deal that settled the disputed 1876 U.S. Presidential election and ended Congressional Reconstruction. Through it, Republican Rutherford B. Hayes was awarded the White House over Democrat Samuel J...

, following the 1876 Presidential election crisis. Later, Johnston gave a speech in 1878 in Congress against the railroad, specifically Bill No. 942, which he viewed as "a positive menace to the commercial interests of the South."

Funder and Readjuster debate

Another issue that marked Johnston's career was the Funder vs. Readjuster debate. Funders maintained that the state was obligated to pay back its entire pre-War debt, whereas the Readjusters suggested differing, lesser figures, regarding how much was owed. The controversy culminated in the end of the Conservative Party in Virginia and the formation of the Readjuster PartyReadjuster Party

The Readjuster Party was a political coalition formed in Virginia in the late 1870s during the turbulent period following the American Civil War. Readjusters aspired "to break the power of wealth and established privilege" and to promote public education, a program which attracted biracial support....

and the Democratic Party

Democratic Party (United States)

The Democratic Party is one of two major contemporary political parties in the United States, along with the Republican Party. The party's socially liberal and progressive platform is largely considered center-left in the U.S. political spectrum. The party has the lengthiest record of continuous...

. William Mahone was chosen as head of the Readjusters and they gained control of the state legislature in 1879, but not the governorship. The legislature then elected Mahone as the successor to Democrat Robert E. Withers

Robert E. Withers

Robert Enoch Withers was an American physician, military officer, newspaperman, politician and diplomat. He represented Virginia in the United States Senate and served as U.S. Consul in Hong Kong.-Biography:...

in the U. S. Senate. However, without a sympathetic governor, they could not enact their reforms. Their next chance came in the election of 1881; their aim was to elect a governor, but most importantly to maintain control of the state legislature, since it would elect "a successor to the Hon. John W. Johnston..." Their party succeeded and the legislature elected prominent Readjuster, and Mahone's "intimate friend", Harrison H. Riddleberger

Harrison H. Riddleberger

Harrison Holt Riddleberger was an American lawyer, newspaper editor, and politician from Woodstock, Virginia. He served in the Virginia House of Delegates and State Senate, and was U.S. Senator from Virginia from 1883 to 1889....

to replace Johnston, eighty-one to forty-nine.

Death and legacy

After serving in the Senate, Johnston resumed his legal practice. He died in Richmond, VirginiaRichmond, Virginia

Richmond is the capital of the Commonwealth of Virginia, in the United States. It is an independent city and not part of any county. Richmond is the center of the Richmond Metropolitan Statistical Area and the Greater Richmond area...

, on February 27, 1889, aged seventy. He was conscious until his death and was aware that he was dying. On March 1, his family brought his body from Richmond to Wytheville, where he was buried in St. Mary's Cemetery.

On May 11, 1903, a ceremony was held to install the portraits of deceased judges in the Washington County Courthouse. David F. Bailey was the speaker that presented the portrait of Johnston. In his speech, he described Johnston:

Johnston was outlived by his wife, Nicketti, who died on June 9, 1908, aged eighty-nine.

Works

- The True Southern Pacific Railroad Versus the Texas Pacific Railroad: Speech of Hon. John W. Johnston 1878

- Repudiation in Virginia, The North American Review. Volume 134, Issue 303. University of Northern Iowa, Cedar Falls, Iowa. February 1882.

- Railway Land-grants, The North American Review. Volume 140, Issue 340. University of Northern Iowa, Cedar Falls, Iowa. March 1885

- The True South vs the Silent South, The CenturyThe Century MagazineThe Century Magazine was first published in the United States in 1881 by The Century Company of New York City as a successor to Scribner's Monthly Magazine...

. Volume 32, Issue 1. The Century CompanyThe Century CompanyThe Century Company was an American publishing company, founded in 1881.It was originally a subsidiary of Charles Scribner's Sons, but was bought and renamed. The magazine it had published up to that time, Scribners Monthly, was renamed The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine.The Century Company...

, New York. May 1886