.gif)

John Floyd (Virginia politician)

Encyclopedia

John Floyd was a Virginia

politician and soldier. He represented Virginia in the United States House of Representatives

and later served as the 25th Governor of Virginia

.

During his career in the House of Representatives, Floyd was an advocate of settling the Oregon Territory

, unsuccessfully arguing on its behalf from 1820 until he left Congress in 1829; the area did not become a territory of the United States until 1848.

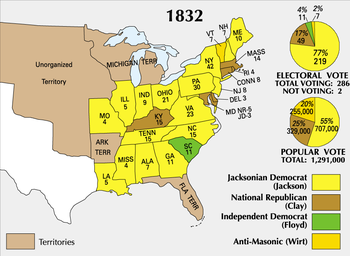

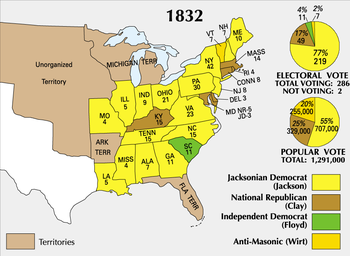

In 1832, Floyd received votes for the Presidency of the United States

, running in the Nullifier Party

, which was succeeded by the Democratic Party

. He carried South Carolina and its 11 electoral votes

. While governor of Virginia, the Nat Turner slave rebellion

occurred and Floyd initially supported emancipation of slavery, but eventually went with the majority. His term as governor saw economic prosperity for the state.

. His parents were pioneer John Floyd

, who was killed by Native Americans twelve days before his son's birth, and Jane Buchanan. His first cousin was Charles Floyd

, the only member of the Lewis and Clark Expedition

to die.

Floyd was educated at home and at a nearby log schoolhouse before enrolling in Dickinson College

in Carlisle, Pennsylvania

at the age of thirteen. He became a member of the Union Philosophical Society in 1797. Although he matriculated with the class of 1798, he had to withdraw due to financial troubles. His guardian had failed in his payments and family accounts relate Floyd was so poor that "he was obliged to borrow a pair of panteloons from a boatman" to return to his home in Kentucky.

When his step-father, Alexander Breckinridge, died in 1801, he was able to return, but had to withdraw again due to a lung illness. He moved to Philadelphia and was placed under the care of Dr. Benjamin Rush

, an experience that influenced his decision to pursue a medical career. After an apprenticeship in Louisville, Kentucky

, Floyd enrolled in the medical department of the University of Pennsylvania

in Philadelphia

in 1804 and became an honorary member of the Philadelphia Medical Society and a member of the Philadelphia Medical Lyceum. Floyd was graduated in 1806 and his graduating dissertation was entitled An Enquiry into the Medical Properties of the Magnolia Tripetala and Magnolia Acuminata. He moved to Lexington, Virginia

and then to the town of Christiansburg, Virginia

. Floyd also served as a Justice of the Peace

in 1807.

In 1804 Floyd married Letitia Preston, who came from a prominent southwest Virginian family. She was the daughter of William Preston

and Susannah Smith, and sister of Francis Preston

, of Abingdon, Washington County Virginia. They had 12 children, including:

Floyd was a surgeon with the rank of major

in the Virginia State Militia

from 1807 to 1812. At the outbreak of the War of 1812

, Floyd moved his family to a new home near present-day Virginia Tech to be near friends and entered the regular army. On July 13, 1813, he was appointed surgeon of Lt. Col. James McDowell's Flying Camp in the Virginia militia. When he returned from a leave of absence, he discovered someone else had been appointed to replace him, and so his service in this role ended on November 16, 1813. Floyd was then commissioned as major of the militia on April 20, 1814 and was promoted to the rank of brigadier general

of the 17th Brigade of Virginia militia. He served until he was elected to the Virginia House of Delegates

in 1814. During this time, he moved his family again, this time to Thorn Spring, a large plantation in Montgomery County, Virginia

. Thornspring (Pulaski

) (Thornspring Golf Course) was inherited by Letitia Preston Floyd from her father William Preston and was located near her older brother, Virginia Treasurer, Gen John Preston, and his Horseshoe Bottoms Plantation (Radford Army Ammunition Plant

). They both were near the Prestons Smithfield

home (Virginia Tech) that their father had completed in Montgomery county for their mother, Susannah Smith Preston, before he died. John Floyd use to keep Bears chained to the tree on the lawns of the Thornspring Plantation (Pulaski, VA).

and established a record as a strong nationalist. He supported a joint resolution to coordinate Virginia's defense with the Federal government as opposed to the contending resolution to "authorize the governor to 'communicate' with the 'Government of the United States. In addition, Floyd supported a bill that authorized Virginia to raise troops and place them at the order of the federal government, as well as supporting a resolution to condemn the terms of peace proposed by the British commissioners at Ghent. He was also an opponent of the tactics of the Federalist

leader, Charles F. Mercer

, who questioned whether the United States was a sovereign country.

In 1816, Floyd was elected as a Democratic-Republican

to the United States House of Representatives, and served from March 4, 1817 to March 3, 1829. When Henry Clay

's proposition to send a minister to Buenos Aires

and therefore recognize Argentina in its bid for independence from Spain, Floyd was in support and urged recognition as a matter of national self-interest and justice. As Floyd's biographer noted:

When General Andrew Jackson

tried and executed two British agents during the First Seminole War in Spanish-held Florida

, it precipitated the Great Seminole Debate of 1818–1819 in Congress, with some claiming he exceeded his orders from President James Monroe

and demanding his censure. Floyd, however, supported Jackson's actions, maintaining he had acted according to precedent and his orders. He also denied the sovereignty of the Seminole

tribes.

When Missouri

sought statehood in 1820, it sparked a heated debate that eventually ended with the Missouri Compromise

, which allowed it to be a slave state with the admission of Maine

as a free state. Prior to this compromise, various proposals were floated all swirling around allowing or prohibiting slavery in the new state. A majority of Virginia's representatives in Congress desired the retention of slavery in Missouri at any price, however Floyd was silent, and his biographer, Ambler, has inferred from various statements made by Floyd, that he preferred immediate statehood to an extension of slavery, though admits there is "little evidence to show that he opposed the latter on general principles." However, when anti-slavery forces in Congress tried to expunge a clause in Missouri's state constitution that would have prevented free blacks from settling in the state, Floyd opposed on the principal of state's rights to decide its own matters and also because he was opposed to the growing Federal power. He stated:

Floyd's position was that Congress had allowed Missouri to become a sovereign state and that now its only choice was whether or not to admit it into the Union. Missouri came up again during the Presidential election of 1820. At issue was whether its electoral votes were valid, since it was still awaiting final approval of its constitution by the Congress. Floyd argued for counting its votes and the "debate which followed precipitated one of the liveliest 'scenes' ever witnessed...". Disorder followed, and both Floyd and John Randolph

were "so persistent in their interruptions as to necessitate an adjournment of the joint session". A compromise was brought forward to count it as "so many with the vote of Missouri and so many without it", but both Randolph and Floyd opposed this, which later prompted John Quincy Adams

to describe their action as "an effort to bring Missouri into the Union 'by storm.'"

Since the end of the War of 1812, the Oregon Territory

Since the end of the War of 1812, the Oregon Territory

was claimed by both Britain and the United States, but neither side pressed their claim. Floyd wanted to pursue America's interests there more aggressively and so on December 20, 1820, he brought this question, the first person to do so, to the attention of Congress with a resolution to appoint a committee and "inquire into the situation of the settlements upon the Pacific Ocean and the expediency of occupying the Columbia River." The resolution passed and the committee was formed with Floyd as the chairman, and Thomas Metcalfe

of Kentucky

and Thomas Van Swearingen

of Virginia as members. Floyd presented the committee's report on January 21, 1821, along with a bill to authorize the occupation of the Columbia River area. Nothing happened with the bill, and John Quincy Adams

criticized Floyd and characterized him as "a 'flaunting' canvasser and a politician seeking to win prestige and patronage, particularly the latter, by a vigorous opposition to the party in power" and attributed his motives for occupation by "a desire to provide a retreat for a defaulting relative and possibly for himself." Floyd then brought forth a resolution on December 10, 1821, to inquire into the expediency of occupying the area, and a week later presented another resolution to have the Secretary of the Navy give an estimate for a survey of harbors on the Pacific Coast.

On January 18, 1822, he introduced a bill to authorize and require the president to occupy "the territory of the United States" on the waters of the Columbia River and to organize the territory north of the 42d parallel of latitude and west of the Rocky Mountains as the "Territory of Oregon" as soon as the population reached 2000. Floyd then asked that all the correspondence relating to the Treaty of Ghent

be presented to the House, which was possibly done in an attempt to damage John Quincy Adams' political ambitions by intimating that his negotiation neglected the United States' interests in the West. However, Floyd's bill was unsuccessful, as was possible attempt to discredit Adams. Floyd next capitalized on the fear of Russia's claims of sovereignty in the area and succeeded in having a resolution adopted asking the president to inform the House whether any foreign government had communicated any claims to the territory, but the information was then deemed too sensitive to disclose to the House.

Not deterred in his attempt to discredit Adams, Floyd learned of a letter written by Jonathan Russell

to James Monroe

on December 15, 1814 that contained "proof positive" of Adams' neglect of the West in the treaty negotiations and he was successful in passing a resolution of inquiry that gave him the letter, but his actions backfired when the press attacked Floyd and forced him to defend his conduct. Adams certainly saw it as an attempt to damage his chances for the presidency. When President Monroe acknowledged that it was time to consider the rights of the United States in this area in December 1822, Floyd reintroduced his bill, and argued for its passage. When a vote was taken on January 27, 1823, it failed to pass by a tally of 61 to 100. Throughout the rest of 1823 and 1824, Floyd continued in his pursuit, and when President Monroe suggested that the second session of the 18th United States Congress

look into establishing a military base at the mouth of the Columbia River, Floyd reintroduced his bill. He argued:

His bill passed this time, with a vote of 115 to 57, but if failed in the Senate. He continued to argue for settling Oregon throughout the rest of his term in Congress.

. However, malfeasance charges were brought up against Crawford and a select committee was formed to investigate the charges, the chairman of which was Floyd. Crawford rivals were determined to remove Floyd, as it was known he favored Crawford's candidacy, but their efforts failed. The committee acquitted Crawford of the charges.

The 1828 presidential election did not have a clear front runner at first for the southern politicians. They were united in their determination to unseat Adams, but thought at first that Andrew Jackson's time had passed after his unsuccessful bid in 1824. However, his popularity had grown, and convinced that Jackson could serve as a figure head only, while the cabinet ran things, an alliance was formed between northern "plain republicans", with Martin Van Buren

as their spokesperson, and southern "planters", with Senator Littleton Waller Tazewell

of Virginia, an intimate friend of Floyd, as their spokesperson, to put Jackson in the White House

. Floyd later wrote:

Floyd worked hard on Jackson's behalf and considered his efforts sufficient for a post in the new cabinet, and so declined to run again for Congress. However, he did not receive this post.

from 1830 to 1834. A rift was already forming between Floyd and other Southern politicians, as Jackson failed to act of the tariff issue and other matters. On December 27, 1830, Floyd wrote to a friend:

In January 1831, Floyd was successful in his bid for re-election as governor, this time for three years, and as the first governor under the new state constitution enacted in 1830. Virginia's economy had seen an upswing under his stewardship and in his December address he wanted to see this continue. He unveiled a "bold economic program" that included a network of state-subsidized internal improvements designed to make Virginia a "commercial empire". The success of his plan and Virginia's future, however, depended on national politics and who captured the White House in 1832. His preoccupation with economic growth for Virginia, and how the Jackson plans were threatening this, made him different from other southern "nullifiers", whose main fear was the abolition of slavery. Floyd opposed slavery, but purely for economic reasons as he viewed it as inefficient. "Though an implacable Southern-rights man, the governor was a foe of the peculiar institution."

The presidential election of 1832 was approaching, and Floyd was torn: He wanted to see Vice President Calhoun as the presidential candidate, but wondered if he should first be proposed as the vice presidential candidate for the second term. He felt Calhoun had a better chance to beat Jackson than Clay, and he wrote to Calhoun in April 1831 to know his opinion: "Under all these views I really do not know which course to take; whether to announce you a candidate for the presidency and take the hazard of war, or wait the fate of Clay. We would be glad to know your opinion about these things." Floyd, along with Tazewell and Tyler, were considered the leaders of the Virginians that had become disaffected with Jackson and had turned to Calhoun. They felt that Jackson had repudiated "virtue and ability as well as Old Republican tenets." According to historian Stephen Oates, "In Floyd's opinion, the federal government under "King Andrew" had usurped power left and right, thus allowing the majority to run roughshod over the minority."

Clay, however, did not agree to postpone his bid for presidency in favor of Calhoun, and Calhoun did not put himself forward. At some point, Floyd went home to rest for a time, and then returned to in time to witness his political friends courting the Anti-Masonic party

and their candidate for president, William Wirt

. Floyd "refused absolutely to have anything to do with one of Wirt's 'laxity in morals' and 'opportune' political thinking; with one who would turn the federal government over to 'fanatics, knaves, and religious bigots.'" Floyd however, ceased his objections against Jackson for a time.

It was at this time, that the Nat Turner

slave rebellion occurred on August 21, 1831. In November, he decided to recommend to the General Assembly gradual abolition of slavery, either for the whole state, or for the counties west of the Blue Ridge Mountains if the former could not be attained, but with a goal for abolition for the whole state in time. However, something caused him to change his mind, for his annual message did not contain this recommendation. Instead he encouraged delegates from the western counties to introduce its discussion. However, the debate became heated and Floyd and others "became alarmed" and eastern delegates talked of splitting the state. As Floyd observed: "a sensation had been engendered which required great delicacy and caution in touching." As a result, a vote was instead put forth on whether the state should legislate this issue. The pro-slavery party narrowly won sixty-seven to sixty. During Floyd's address to the General Assembly, he did, however, touch upon the national issues swirling around the country. As Floyd's biographer noted:

When the Democratic Party announced that Van Buren would be their vice presidential candidate, Floyd was not happy. He renewed his antagonism with Jackson accordingly. Floyd felt that Van Buren's would inject "Northern principles" into the government and would "lead with a rapidity of lightening [sic] to the sudden and immediate emancipation of slavery". Virginians led the movement to prevent Van Buren's election. Philip P. Barbour was brought forward as a running mate on a Jackson-Barbour ticket. "In this way Floyd expected to throw the choice of the vice-president into the Senate, where, it was thought, Van Buren's election could be prevented." As historian William J. Cooper noted, "For the Calhounites in Virginia, replacing Van Buren with Barbour would achieve two desired goals: eliminate the man they designated as the great enemy both of Calhoun and of the Virginia doctrine as well as symbolize the political resurgence of Virginia." Barbour, however, later withdrew his candidacy to accept Jackson's appointment as judge of the United States Circuit Court

for the Eastern District of Virginia

, and Van Buren became Vice President.

The Nullification Crisis

The Nullification Crisis

had been ongoing since 1828, and in December 1832, Jackson came down squarely against "the nullifiers" in his proclamation. However, in the presidential election of 1832, Jackson confirmed his power in the South by winning his re-election. Jackson had skillfully neutralized Barbour's movement, and Clay did not even appear on several southern tickets. It was only in Calhoun's stronghold of South Carolina that Jackson did not fare well: they put all their electoral votes (11) for Floyd, their ally, for President of the United States.

Floyd's biographer commented that despite advocating moderation in his annual message in December 1832, he was "secretly counting the costs and horrors of war" and that Floyd characterized Jackson's Proclamation in response to South Carolina's Nullification Ordinance as an "outrage upon our institutions" and a "satire upon the revolution" making war inevitable. A letter to Tazewell at this time called Jackson the "tyrant usurper" and feared a civil war would be the result. When Floyd learned that Clay was willing to compromise on the tariff and that South Carolina would submit her issues to a "convention of the states", he supported both. The crisis averted, he toned down his opposition to Jackson, but was unwilling to return to the Democratic Party while Van Buren was the leader. As a result, he turned to Clay, and attempted to bring him and John C. Calhoun

together in a new political party to support these views. "... the elimination of both Clay and Calhoun from the list of eligibles for the presidency had become temporarily imperative. Accordingly Floyd set himself to the task of working out a fighting alliance between all the factions opposed to the administration. To this end he encouraged discord within the Democratic party, while scrupulously keeping the conflicting ambitions of his own friends in the background." This was the beginnings of the Whig Party

.

Floyd suffered a stroke in 1834 while still in office, but was able to serve out his term. He approached Littleton Waller Tazewell to be his successor, who was ultimately successful. "Believing that 'great events are in the gale' he urged Tazewell to hasten to Richmond and to be prepared to lay down his share in the power of the state as he had it down for the 'Confederacy,' 'uninjured and undiminished. On April 16, 1834, he left Richmond for his home, escorted by Bigger's Blues, Richardson's Artillery, Myer's Cavalry, and Richardson's Riflemen, Richmond's volunteer companies.

Floyd suffered a stroke and died on August 17, 1837, in Sweet Springs

in Monroe County, Virginia

(now West Virginia

), and his tombstone can be found in the Lewis Family Cemetery, on the hill behind the remains of the historic Lynnside Manor

. His grave is near to that of John Lewis.

On January 15, 1831, the General Assembly of Virginia passed an act creating the present county of Floyd

out of Montgomery County

, named after Floyd, who was governor at the time.

Virginia

The Commonwealth of Virginia , is a U.S. state on the Atlantic Coast of the Southern United States. Virginia is nicknamed the "Old Dominion" and sometimes the "Mother of Presidents" after the eight U.S. presidents born there...

politician and soldier. He represented Virginia in the United States House of Representatives

United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives is one of the two Houses of the United States Congress, the bicameral legislature which also includes the Senate.The composition and powers of the House are established in Article One of the Constitution...

and later served as the 25th Governor of Virginia

Governor of Virginia

The governor of Virginia serves as the chief executive of the Commonwealth of Virginia for a four-year term. The position is currently held by Republican Bob McDonnell, who was inaugurated on January 16, 2010, as the 71st governor of Virginia....

.

During his career in the House of Representatives, Floyd was an advocate of settling the Oregon Territory

Oregon Territory

The Territory of Oregon was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from August 14, 1848, until February 14, 1859, when the southwestern portion of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Oregon. Originally claimed by several countries , the region was...

, unsuccessfully arguing on its behalf from 1820 until he left Congress in 1829; the area did not become a territory of the United States until 1848.

In 1832, Floyd received votes for the Presidency of the United States

President of the United States

The President of the United States of America is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president leads the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces....

, running in the Nullifier Party

Nullifier Party

The Nullifier Party was a short-lived political party based in South Carolina in the 1830s. Started by John C. Calhoun, it was a states' rights party that supported the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions, holding that States could nullify federal laws within their borders...

, which was succeeded by the Democratic Party

Democratic Party (United States)

The Democratic Party is one of two major contemporary political parties in the United States, along with the Republican Party. The party's socially liberal and progressive platform is largely considered center-left in the U.S. political spectrum. The party has the lengthiest record of continuous...

. He carried South Carolina and its 11 electoral votes

United States Electoral College

The Electoral College consists of the electors appointed by each state who formally elect the President and Vice President of the United States. Since 1964, there have been 538 electors in each presidential election...

. While governor of Virginia, the Nat Turner slave rebellion

Nat Turner

Nathaniel "Nat" Turner was an American slave who led a slave rebellion in Virginia on August 21, 1831 that resulted in 60 white deaths and at least 100 black deaths, the largest number of fatalities to occur in one uprising prior to the American Civil War in the southern United States. He gathered...

occurred and Floyd initially supported emancipation of slavery, but eventually went with the majority. His term as governor saw economic prosperity for the state.

Family and early life

Floyd was born at Floyds Station, Virginia, near what is now Louisville, KentuckyLouisville, Kentucky

Louisville is the largest city in the U.S. state of Kentucky, and the county seat of Jefferson County. Since 2003, the city's borders have been coterminous with those of the county because of a city-county merger. The city's population at the 2010 census was 741,096...

. His parents were pioneer John Floyd

James John Floyd

James John Floyd , better known as John Floyd, was a pioneer of the Midwestern United States around the Louisville, Kentucky area where he worked as a surveyor for land development and as a military figure. Floyd was an early settler of St. Matthews, Kentucky and helped lay out Louisville...

, who was killed by Native Americans twelve days before his son's birth, and Jane Buchanan. His first cousin was Charles Floyd

Charles Floyd (explorer)

Charles Floyd was a United States explorer, a non-commissioned officer in the U.S. Army, and quartermaster in the Lewis and Clark Expedition. A native of Kentucky, he was a relative of William Clark, an uncle to the politician John Floyd, and a brother to James John Floyd...

, the only member of the Lewis and Clark Expedition

Lewis and Clark Expedition

The Lewis and Clark Expedition, or ″Corps of Discovery Expedition" was the first transcontinental expedition to the Pacific Coast by the United States. Commissioned by President Thomas Jefferson and led by two Virginia-born veterans of Indian wars in the Ohio Valley, Meriwether Lewis and William...

to die.

Floyd was educated at home and at a nearby log schoolhouse before enrolling in Dickinson College

Dickinson College

Dickinson College is a private, residential liberal arts college in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. Originally established as a Grammar School in 1773, Dickinson was chartered September 9, 1783, five days after the signing of the Treaty of Paris, making it the first college to be founded in the newly...

in Carlisle, Pennsylvania

Carlisle, Pennsylvania

Carlisle is a borough in and the county seat of Cumberland County, Pennsylvania, United States. The name is traditionally pronounced with emphasis on the second syllable. Carlisle is located within the Cumberland Valley, a highly productive agricultural region. As of the 2010 census, the borough...

at the age of thirteen. He became a member of the Union Philosophical Society in 1797. Although he matriculated with the class of 1798, he had to withdraw due to financial troubles. His guardian had failed in his payments and family accounts relate Floyd was so poor that "he was obliged to borrow a pair of panteloons from a boatman" to return to his home in Kentucky.

When his step-father, Alexander Breckinridge, died in 1801, he was able to return, but had to withdraw again due to a lung illness. He moved to Philadelphia and was placed under the care of Dr. Benjamin Rush

Benjamin Rush

Benjamin Rush was a Founding Father of the United States. Rush lived in the state of Pennsylvania and was a physician, writer, educator, humanitarian and a Christian Universalist, as well as the founder of Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania....

, an experience that influenced his decision to pursue a medical career. After an apprenticeship in Louisville, Kentucky

Louisville, Kentucky

Louisville is the largest city in the U.S. state of Kentucky, and the county seat of Jefferson County. Since 2003, the city's borders have been coterminous with those of the county because of a city-county merger. The city's population at the 2010 census was 741,096...

, Floyd enrolled in the medical department of the University of Pennsylvania

University of Pennsylvania

The University of Pennsylvania is a private, Ivy League university located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States. Penn is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States,Penn is the fourth-oldest using the founding dates claimed by each institution...

in Philadelphia

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Philadelphia is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and the county seat of Philadelphia County, with which it is coterminous. The city is located in the Northeastern United States along the Delaware and Schuylkill rivers. It is the fifth-most-populous city in the United States,...

in 1804 and became an honorary member of the Philadelphia Medical Society and a member of the Philadelphia Medical Lyceum. Floyd was graduated in 1806 and his graduating dissertation was entitled An Enquiry into the Medical Properties of the Magnolia Tripetala and Magnolia Acuminata. He moved to Lexington, Virginia

Lexington, Virginia

Lexington is an independent city within the confines of Rockbridge County in the Commonwealth of Virginia. The population was 7,042 in 2010. Lexington is about 55 minutes east of the West Virginia border and is about 50 miles north of Roanoke, Virginia. It was first settled in 1777.It is home to...

and then to the town of Christiansburg, Virginia

Christiansburg, Virginia

Christiansburg is a town in Montgomery County, Virginia, United States. The population was 21,041 at the 2010 census. It is the county seat of Montgomery County...

. Floyd also served as a Justice of the Peace

Justice of the Peace

A justice of the peace is a puisne judicial officer elected or appointed by means of a commission to keep the peace. Depending on the jurisdiction, they might dispense summary justice or merely deal with local administrative applications in common law jurisdictions...

in 1807.

In 1804 Floyd married Letitia Preston, who came from a prominent southwest Virginian family. She was the daughter of William Preston

William Preston (Virginia)

Col. William Preston played a crucial role in surveying and developing the colonies going westward, exerted great influence in the colonial affairs of his time, ran a large plantation, and founded a dynasty whose progeny would supply leaders for the South for nearly a century...

and Susannah Smith, and sister of Francis Preston

Francis Preston

Francis Preston was an American lawyer and politician from Abingdon, Virginia. He served in both houses of the state legislature and represented Virginia in the U.S...

, of Abingdon, Washington County Virginia. They had 12 children, including:

- John Buchanan Floyd, (1806–1863), Governor of Virginia, and Secretary of War under President Buchanan.

- Nicketti Buchanan Floyd, married United States Senator John Warfield Johnston.

- George Rogers Clark FloydGeorge Rogers Clark FloydGeorge Rogers Clark Floyd was a West Virginia politician and businessman. He served as the Secretary of Wisconsin Territory from 1843 to 1846, and served in the West Virginia House of Delegates from 1872 to 1873....

, Secretary of Wisconsin Territory and later a member of the West Virginia LegislatureWest Virginia LegislatureThe West Virginia Legislature is the state legislature of the U.S. state of West Virginia. A bicameral legislative body, the Legislature is split between the upper Senate and the lower House of Delegates. It was established under Article VI of the West Virginia Constitution following the state's... - Eliza Lavalette Floyd, married professor George Frederick HolmesGeorge Frederick HolmesGeorge Frederick Holmes was the first Chancellor of the University of Mississippi, from 1848 to 1849.-Biography:George Frederick Holmes was born in 1820 in Georgetown, British Guyana...

Floyd was a surgeon with the rank of major

Major

Major is a rank of commissioned officer, with corresponding ranks existing in almost every military in the world.When used unhyphenated, in conjunction with no other indicator of rank, the term refers to the rank just senior to that of an Army captain and just below the rank of lieutenant colonel. ...

in the Virginia State Militia

Militia

The term militia is commonly used today to refer to a military force composed of ordinary citizens to provide defense, emergency law enforcement, or paramilitary service, in times of emergency without being paid a regular salary or committed to a fixed term of service. It is a polyseme with...

from 1807 to 1812. At the outbreak of the War of 1812

War of 1812

The War of 1812 was a military conflict fought between the forces of the United States of America and those of the British Empire. The Americans declared war in 1812 for several reasons, including trade restrictions because of Britain's ongoing war with France, impressment of American merchant...

, Floyd moved his family to a new home near present-day Virginia Tech to be near friends and entered the regular army. On July 13, 1813, he was appointed surgeon of Lt. Col. James McDowell's Flying Camp in the Virginia militia. When he returned from a leave of absence, he discovered someone else had been appointed to replace him, and so his service in this role ended on November 16, 1813. Floyd was then commissioned as major of the militia on April 20, 1814 and was promoted to the rank of brigadier general

Brigadier General

Brigadier general is a senior rank in the armed forces. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries, usually sitting between the ranks of colonel and major general. When appointed to a field command, a brigadier general is typically in command of a brigade consisting of around 4,000...

of the 17th Brigade of Virginia militia. He served until he was elected to the Virginia House of Delegates

Virginia House of Delegates

The Virginia House of Delegates is the lower house of the Virginia General Assembly. It has 100 members elected for terms of two years; unlike most states, these elections take place during odd-numbered years. The House is presided over by the Speaker of the House, who is elected from among the...

in 1814. During this time, he moved his family again, this time to Thorn Spring, a large plantation in Montgomery County, Virginia

Montgomery County, Virginia

As of the census of 2000, there were 83,629 people, 30,997 households, and 17,203 families residing in the county. The population density was 215 people per square mile . There were 32,527 housing units at an average density of 84 per square mile...

. Thornspring (Pulaski

Pulaski

Pulaski most commonly refers to Casimir Pulaski , a Polish military commander and American Revolutionary War hero.-Municipalities in the United States:* Pulaski, Georgia...

) (Thornspring Golf Course) was inherited by Letitia Preston Floyd from her father William Preston and was located near her older brother, Virginia Treasurer, Gen John Preston, and his Horseshoe Bottoms Plantation (Radford Army Ammunition Plant

Radford Army Ammunition Plant

The primary mission of Radford Army Ammunition Plant is to manufacture propellants and explosives in support of field artillery, air defense, tank, missile, aircraft and Navy weapons systems...

). They both were near the Prestons Smithfield

Smithfield, Virginia

Smithfield is a town in Isle of Wight County, in the South Hampton Roads subregion of the Hampton Roads region of Virginia in the United States. The population was 8,089 at the 2010 census....

home (Virginia Tech) that their father had completed in Montgomery county for their mother, Susannah Smith Preston, before he died. John Floyd use to keep Bears chained to the tree on the lawns of the Thornspring Plantation (Pulaski, VA).

Political career

From 1814 to 1815, Floyd was a member of the Virginia House of DelegatesVirginia House of Delegates

The Virginia House of Delegates is the lower house of the Virginia General Assembly. It has 100 members elected for terms of two years; unlike most states, these elections take place during odd-numbered years. The House is presided over by the Speaker of the House, who is elected from among the...

and established a record as a strong nationalist. He supported a joint resolution to coordinate Virginia's defense with the Federal government as opposed to the contending resolution to "authorize the governor to 'communicate' with the 'Government of the United States. In addition, Floyd supported a bill that authorized Virginia to raise troops and place them at the order of the federal government, as well as supporting a resolution to condemn the terms of peace proposed by the British commissioners at Ghent. He was also an opponent of the tactics of the Federalist

Federalist

The term federalist describes several political beliefs around the world. Also, it may refer to the concept of federalism or the type of government called a federation...

leader, Charles F. Mercer

Charles F. Mercer

Charles Fenton Mercer was a nineteenth century politician, U.S. Congressman, and lawyer from Loudoun County, Virginia....

, who questioned whether the United States was a sovereign country.

In 1816, Floyd was elected as a Democratic-Republican

Democratic-Republican Party (United States)

The Democratic-Republican Party or Republican Party was an American political party founded in the early 1790s by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. Political scientists use the former name, while historians prefer the latter one; contemporaries generally called the party the "Republicans", along...

to the United States House of Representatives, and served from March 4, 1817 to March 3, 1829. When Henry Clay

Henry Clay

Henry Clay, Sr. , was a lawyer, politician and skilled orator who represented Kentucky separately in both the Senate and in the House of Representatives...

's proposition to send a minister to Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires is the capital and largest city of Argentina, and the second-largest metropolitan area in South America, after São Paulo. It is located on the western shore of the estuary of the Río de la Plata, on the southeastern coast of the South American continent...

and therefore recognize Argentina in its bid for independence from Spain, Floyd was in support and urged recognition as a matter of national self-interest and justice. As Floyd's biographer noted:

This proposed recognition meant more to Floyd even than trade advantages and justice; it was another step in the disenthrallment of America. It would afford relief from that political plexus which had made it impossible for one European nation to move, even in matters relating to America, without creating a corresponding movement in each of the others. He was tired of negotiating the things which related exclusively to America in London, Paris, and Madrid.

When General Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson was the seventh President of the United States . Based in frontier Tennessee, Jackson was a politician and army general who defeated the Creek Indians at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend , and the British at the Battle of New Orleans...

tried and executed two British agents during the First Seminole War in Spanish-held Florida

Florida

Florida is a state in the southeastern United States, located on the nation's Atlantic and Gulf coasts. It is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the north by Alabama and Georgia and to the east by the Atlantic Ocean. With a population of 18,801,310 as measured by the 2010 census, it...

, it precipitated the Great Seminole Debate of 1818–1819 in Congress, with some claiming he exceeded his orders from President James Monroe

James Monroe

James Monroe was the fifth President of the United States . Monroe was the last president who was a Founding Father of the United States, and the last president from the Virginia dynasty and the Republican Generation...

and demanding his censure. Floyd, however, supported Jackson's actions, maintaining he had acted according to precedent and his orders. He also denied the sovereignty of the Seminole

Seminole

The Seminole are a Native American people originally of Florida, who now reside primarily in that state and Oklahoma. The Seminole nation emerged in a process of ethnogenesis out of groups of Native Americans, most significantly Creeks from what is now Georgia and Alabama, who settled in Florida in...

tribes.

When Missouri

Missouri

Missouri is a US state located in the Midwestern United States, bordered by Iowa, Illinois, Kentucky, Tennessee, Arkansas, Oklahoma, Kansas and Nebraska. With a 2010 population of 5,988,927, Missouri is the 18th most populous state in the nation and the fifth most populous in the Midwest. It...

sought statehood in 1820, it sparked a heated debate that eventually ended with the Missouri Compromise

Missouri Compromise

The Missouri Compromise was an agreement passed in 1820 between the pro-slavery and anti-slavery factions in the United States Congress, involving primarily the regulation of slavery in the western territories. It prohibited slavery in the former Louisiana Territory north of the parallel 36°30'...

, which allowed it to be a slave state with the admission of Maine

Maine

Maine is a state in the New England region of the northeastern United States, bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the east and south, New Hampshire to the west, and the Canadian provinces of Quebec to the northwest and New Brunswick to the northeast. Maine is both the northernmost and easternmost...

as a free state. Prior to this compromise, various proposals were floated all swirling around allowing or prohibiting slavery in the new state. A majority of Virginia's representatives in Congress desired the retention of slavery in Missouri at any price, however Floyd was silent, and his biographer, Ambler, has inferred from various statements made by Floyd, that he preferred immediate statehood to an extension of slavery, though admits there is "little evidence to show that he opposed the latter on general principles." However, when anti-slavery forces in Congress tried to expunge a clause in Missouri's state constitution that would have prevented free blacks from settling in the state, Floyd opposed on the principal of state's rights to decide its own matters and also because he was opposed to the growing Federal power. He stated:

If gentlemen would only expunge from their memories the progress of European liberty and institutions, they would find in America a number of states, or separate, independent, and distinct nations, confederated for common safety, and mutual protection, taught wisdom by the eternal feuds of Spain, England, France, and Germany, now consolidated into large empires. These states before the confederation could make war and peace, raise armies, or build a navy, coin money, pass bankrupt laws, naturalize foreigners, or regulate commerce... Informed by Europe they knew Jealousies would arise, and constant strife render armies in every nation necessary to their defence, which would endanger their liberties and homes. These states then, in their sovereign and independent characters, were willing to enter into a compact, by which the power of making war and peace, and regulating commerce, possessed alike by all, should be transferred to a congress of the states, to be exercised with uniformity, for their mutual benefit; thus avoiding the evils of "superanuated and enslaved" Europe. These two were the only powers ever intended to be granted by the states. All other powers conferred by the compact are necessary to carry these two into execution.

Floyd's position was that Congress had allowed Missouri to become a sovereign state and that now its only choice was whether or not to admit it into the Union. Missouri came up again during the Presidential election of 1820. At issue was whether its electoral votes were valid, since it was still awaiting final approval of its constitution by the Congress. Floyd argued for counting its votes and the "debate which followed precipitated one of the liveliest 'scenes' ever witnessed...". Disorder followed, and both Floyd and John Randolph

John Randolph of Roanoke

John Randolph , known as John Randolph of Roanoke, was a planter and a Congressman from Virginia, serving in the House of Representatives , the Senate , and also as Minister to Russia...

were "so persistent in their interruptions as to necessitate an adjournment of the joint session". A compromise was brought forward to count it as "so many with the vote of Missouri and so many without it", but both Randolph and Floyd opposed this, which later prompted John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams was the sixth President of the United States . He served as an American diplomat, Senator, and Congressional representative. He was a member of the Federalist, Democratic-Republican, National Republican, and later Anti-Masonic and Whig parties. Adams was the son of former...

to describe their action as "an effort to bring Missouri into the Union 'by storm.'"

Oregon Territory

Oregon Territory

The Territory of Oregon was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from August 14, 1848, until February 14, 1859, when the southwestern portion of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Oregon. Originally claimed by several countries , the region was...

was claimed by both Britain and the United States, but neither side pressed their claim. Floyd wanted to pursue America's interests there more aggressively and so on December 20, 1820, he brought this question, the first person to do so, to the attention of Congress with a resolution to appoint a committee and "inquire into the situation of the settlements upon the Pacific Ocean and the expediency of occupying the Columbia River." The resolution passed and the committee was formed with Floyd as the chairman, and Thomas Metcalfe

Thomas Metcalfe (US politician)

Thomas Metcalfe , also known as Thomas Metcalf or as "Stonehammer", was a U.S. Representative, Senator, and the tenth Governor of Kentucky. He was the first gubernatorial candidate in the state's history to be chosen by a nominating convention rather than a caucus...

of Kentucky

Kentucky

The Commonwealth of Kentucky is a state located in the East Central United States of America. As classified by the United States Census Bureau, Kentucky is a Southern state, more specifically in the East South Central region. Kentucky is one of four U.S. states constituted as a commonwealth...

and Thomas Van Swearingen

Thomas Van Swearingen

Thomas Van Swearingen was a U.S. Representative from Virginia.Born near Shepherdstown, Virginia , Van Swearingen attended the common schools.He served as member of the State house of delegates 1814-1816....

of Virginia as members. Floyd presented the committee's report on January 21, 1821, along with a bill to authorize the occupation of the Columbia River area. Nothing happened with the bill, and John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams was the sixth President of the United States . He served as an American diplomat, Senator, and Congressional representative. He was a member of the Federalist, Democratic-Republican, National Republican, and later Anti-Masonic and Whig parties. Adams was the son of former...

criticized Floyd and characterized him as "a 'flaunting' canvasser and a politician seeking to win prestige and patronage, particularly the latter, by a vigorous opposition to the party in power" and attributed his motives for occupation by "a desire to provide a retreat for a defaulting relative and possibly for himself." Floyd then brought forth a resolution on December 10, 1821, to inquire into the expediency of occupying the area, and a week later presented another resolution to have the Secretary of the Navy give an estimate for a survey of harbors on the Pacific Coast.

On January 18, 1822, he introduced a bill to authorize and require the president to occupy "the territory of the United States" on the waters of the Columbia River and to organize the territory north of the 42d parallel of latitude and west of the Rocky Mountains as the "Territory of Oregon" as soon as the population reached 2000. Floyd then asked that all the correspondence relating to the Treaty of Ghent

Treaty of Ghent

The Treaty of Ghent , signed on 24 December 1814, in Ghent , was the peace treaty that ended the War of 1812 between the United States of America and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland...

be presented to the House, which was possibly done in an attempt to damage John Quincy Adams' political ambitions by intimating that his negotiation neglected the United States' interests in the West. However, Floyd's bill was unsuccessful, as was possible attempt to discredit Adams. Floyd next capitalized on the fear of Russia's claims of sovereignty in the area and succeeded in having a resolution adopted asking the president to inform the House whether any foreign government had communicated any claims to the territory, but the information was then deemed too sensitive to disclose to the House.

Not deterred in his attempt to discredit Adams, Floyd learned of a letter written by Jonathan Russell

Jonathan Russell

Jonathan Russell was a United States Representative from Massachusetts and diplomat.Born in Providence, Rhode Island, Russell graduated from Brown University in 1791. He studied law and was admitted to the bar, but did not practice...

to James Monroe

James Monroe

James Monroe was the fifth President of the United States . Monroe was the last president who was a Founding Father of the United States, and the last president from the Virginia dynasty and the Republican Generation...

on December 15, 1814 that contained "proof positive" of Adams' neglect of the West in the treaty negotiations and he was successful in passing a resolution of inquiry that gave him the letter, but his actions backfired when the press attacked Floyd and forced him to defend his conduct. Adams certainly saw it as an attempt to damage his chances for the presidency. When President Monroe acknowledged that it was time to consider the rights of the United States in this area in December 1822, Floyd reintroduced his bill, and argued for its passage. When a vote was taken on January 27, 1823, it failed to pass by a tally of 61 to 100. Throughout the rest of 1823 and 1824, Floyd continued in his pursuit, and when President Monroe suggested that the second session of the 18th United States Congress

18th United States Congress

The Eighteenth United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C. from March 4, 1823 to March 3, 1825, during the seventh and eighth...

look into establishing a military base at the mouth of the Columbia River, Floyd reintroduced his bill. He argued:

I ... appeal to the House to consider well our interests in the Western Ocean, on our western coast, and the trade to China and India; and the ease with which it can be brought down the Missouri. What is this commerce? Thousands of years have passed by, and, year after year, all the nations of the earth have, each year, sought the rich commerce of that country; all have enjoyed the riches of the East. That trade was sought by King Solomon, by Tyre, Sidon; this wealth found its way to Egypt, and at last to Rome, to France, Portugal, Spain, Holland, England, and finally to this Republic. How vast and incomparably rich must be that country and commerce, which has never ceased, one day, from the highest point of Jewish splendor to the instant that I am speaking, to supply the whole globe with all the busy imagination of man can desire for his ease, comfort, and enjoyment! Whilst we Rave so fair an opportunity offered to participate so largely in all this wealth and enjoyment, if not to govern and direct the whole, can it be possible that doubt, or mere points of speculation, will weigh with the House and cause us to lose forever the brightest prospect ever presented to the eyes of a nation?"

His bill passed this time, with a vote of 115 to 57, but if failed in the Senate. He continued to argue for settling Oregon throughout the rest of his term in Congress.

Role in Presidential elections

In the period leading up to the 1824 presidential election, a leading candidate was William H. CrawfordWilliam H. Crawford

William Harris Crawford was an American politician and judge during the early 19th century. He served as United States Secretary of War from 1815 to 1816 and United States Secretary of the Treasury from 1816 to 1825, and was a candidate for President of the United States in 1824.-Political...

. However, malfeasance charges were brought up against Crawford and a select committee was formed to investigate the charges, the chairman of which was Floyd. Crawford rivals were determined to remove Floyd, as it was known he favored Crawford's candidacy, but their efforts failed. The committee acquitted Crawford of the charges.

The 1828 presidential election did not have a clear front runner at first for the southern politicians. They were united in their determination to unseat Adams, but thought at first that Andrew Jackson's time had passed after his unsuccessful bid in 1824. However, his popularity had grown, and convinced that Jackson could serve as a figure head only, while the cabinet ran things, an alliance was formed between northern "plain republicans", with Martin Van Buren

Martin Van Buren

Martin Van Buren was the eighth President of the United States . Before his presidency, he was the eighth Vice President and the tenth Secretary of State, under Andrew Jackson ....

as their spokesperson, and southern "planters", with Senator Littleton Waller Tazewell

Littleton Waller Tazewell

Littleton Waller Tazewell was a U.S. Representative, U.S. Senator from and the 26th Governor of Virginia.Tazewell, son of Henry Tazewell, was born in Williamsburg, Virginia, where his grandfather Benjamin Waller was a lawyer who taught him Latin...

of Virginia, an intimate friend of Floyd, as their spokesperson, to put Jackson in the White House

White House

The White House is the official residence and principal workplace of the president of the United States. Located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., the house was designed by Irish-born James Hoban, and built between 1792 and 1800 of white-painted Aquia sandstone in the Neoclassical...

. Floyd later wrote:

"At this moment [1828] came the direful struggle between the great parties in Congress founded upon the claim which the majority ... from the north of the Potomac made to the right to lay any tax upon the importations into the United States which was intended to act as a protection to northern manufacturers by excluding foreign fabrics of the same kind. Hence all the states to the south of the Potomac became dependent upon the Northern States for a supply of whatever thing they might want, and in this way the South was compelled to sell its products low and buy from the North all articles it needed from twenty-five to one hundred and twenty-five per cent higher than from France to England ... At this juncture the southern party brought out Jackson."

Floyd worked hard on Jackson's behalf and considered his efforts sufficient for a post in the new cabinet, and so declined to run again for Congress. However, he did not receive this post.

Governor of Virginia

Floyd was Governor of VirginiaGovernor of Virginia

The governor of Virginia serves as the chief executive of the Commonwealth of Virginia for a four-year term. The position is currently held by Republican Bob McDonnell, who was inaugurated on January 16, 2010, as the 71st governor of Virginia....

from 1830 to 1834. A rift was already forming between Floyd and other Southern politicians, as Jackson failed to act of the tariff issue and other matters. On December 27, 1830, Floyd wrote to a friend:

As you long ago wrote me, and told me personally, nay predicted, Jackson has thrown me overboard; he is not only unwilling to give me employment, as he promised after I declined a reelection to Congress, but has in every single instance refused office to my friends, and even respectful consideration to my letters of recommendation to others. Nor does he stop here. I am at this moment enduring the whole weight of the opposition to him, his friends, and the power and patronage of his government to break down myself and my friends in Virginia, and to prevent my reelection to the office I now fill. Without having much reputation for political matters, I have read those folks at Washington thoroughly ... I am not of a temper to pocket insult, neglect, or injury. I have, my dear friend, determined on my course. I can be as silent and patient as any of my aboriginal ancestors, and like them I feel that vengeance would be sweet, but when the day of retribution shall come, it will be marked by the effects of the tomahawk. You must know that notwithstanding all efforts to prevent it I calculate on a reelection. Then I will begin to formulate a message in which, as you know, my own principles will be maintained.

In January 1831, Floyd was successful in his bid for re-election as governor, this time for three years, and as the first governor under the new state constitution enacted in 1830. Virginia's economy had seen an upswing under his stewardship and in his December address he wanted to see this continue. He unveiled a "bold economic program" that included a network of state-subsidized internal improvements designed to make Virginia a "commercial empire". The success of his plan and Virginia's future, however, depended on national politics and who captured the White House in 1832. His preoccupation with economic growth for Virginia, and how the Jackson plans were threatening this, made him different from other southern "nullifiers", whose main fear was the abolition of slavery. Floyd opposed slavery, but purely for economic reasons as he viewed it as inefficient. "Though an implacable Southern-rights man, the governor was a foe of the peculiar institution."

The presidential election of 1832 was approaching, and Floyd was torn: He wanted to see Vice President Calhoun as the presidential candidate, but wondered if he should first be proposed as the vice presidential candidate for the second term. He felt Calhoun had a better chance to beat Jackson than Clay, and he wrote to Calhoun in April 1831 to know his opinion: "Under all these views I really do not know which course to take; whether to announce you a candidate for the presidency and take the hazard of war, or wait the fate of Clay. We would be glad to know your opinion about these things." Floyd, along with Tazewell and Tyler, were considered the leaders of the Virginians that had become disaffected with Jackson and had turned to Calhoun. They felt that Jackson had repudiated "virtue and ability as well as Old Republican tenets." According to historian Stephen Oates, "In Floyd's opinion, the federal government under "King Andrew" had usurped power left and right, thus allowing the majority to run roughshod over the minority."

Clay, however, did not agree to postpone his bid for presidency in favor of Calhoun, and Calhoun did not put himself forward. At some point, Floyd went home to rest for a time, and then returned to in time to witness his political friends courting the Anti-Masonic party

Anti-Masonic Party

The Anti-Masonic Party was the first "third party" in the United States. It strongly opposed Freemasonry and was founded as a single-issue party aspiring to become a major party....

and their candidate for president, William Wirt

William Wirt (Attorney General)

William Wirt was an American author and statesman who is credited with turning the position of United States Attorney General into one of influence.-History:...

. Floyd "refused absolutely to have anything to do with one of Wirt's 'laxity in morals' and 'opportune' political thinking; with one who would turn the federal government over to 'fanatics, knaves, and religious bigots.'" Floyd however, ceased his objections against Jackson for a time.

It was at this time, that the Nat Turner

Nat Turner

Nathaniel "Nat" Turner was an American slave who led a slave rebellion in Virginia on August 21, 1831 that resulted in 60 white deaths and at least 100 black deaths, the largest number of fatalities to occur in one uprising prior to the American Civil War in the southern United States. He gathered...

slave rebellion occurred on August 21, 1831. In November, he decided to recommend to the General Assembly gradual abolition of slavery, either for the whole state, or for the counties west of the Blue Ridge Mountains if the former could not be attained, but with a goal for abolition for the whole state in time. However, something caused him to change his mind, for his annual message did not contain this recommendation. Instead he encouraged delegates from the western counties to introduce its discussion. However, the debate became heated and Floyd and others "became alarmed" and eastern delegates talked of splitting the state. As Floyd observed: "a sensation had been engendered which required great delicacy and caution in touching." As a result, a vote was instead put forth on whether the state should legislate this issue. The pro-slavery party narrowly won sixty-seven to sixty. During Floyd's address to the General Assembly, he did, however, touch upon the national issues swirling around the country. As Floyd's biographer noted:

In clear and forceful language Floyd reasserted the state sovereignty theory of government, as guaranteed by the 'Compact or Constitution,' holding the Federal Government to be merely the 'Agent of the States' entrusted only with such powers as were originally intended to operate 'externally' and 'upon nations foreign to those composing the Confederacy.' He called attention to the disregard with which 'an unrestrained majority' had received the memorials and protests of some of the 'sovereign states,' justifying their acts by precedent and expediency and thus melting away 'the solder of the Federal chain;' also to the fact that it was then 'strongly insinuated' that the states could not 'interpose to arrest an unconstitutional measure.' Such a course, he was certain, could result only in nullifying the federal constitution and in a complete failure in our experiment in government.

When the Democratic Party announced that Van Buren would be their vice presidential candidate, Floyd was not happy. He renewed his antagonism with Jackson accordingly. Floyd felt that Van Buren's would inject "Northern principles" into the government and would "lead with a rapidity of lightening [sic] to the sudden and immediate emancipation of slavery". Virginians led the movement to prevent Van Buren's election. Philip P. Barbour was brought forward as a running mate on a Jackson-Barbour ticket. "In this way Floyd expected to throw the choice of the vice-president into the Senate, where, it was thought, Van Buren's election could be prevented." As historian William J. Cooper noted, "For the Calhounites in Virginia, replacing Van Buren with Barbour would achieve two desired goals: eliminate the man they designated as the great enemy both of Calhoun and of the Virginia doctrine as well as symbolize the political resurgence of Virginia." Barbour, however, later withdrew his candidacy to accept Jackson's appointment as judge of the United States Circuit Court

United States circuit court

The United States circuit courts were the original intermediate level courts of the United States federal court system. They were established by the Judiciary Act of 1789. They had trial court jurisdiction over civil suits of diversity jurisdiction and major federal crimes. They also had appellate...

for the Eastern District of Virginia

United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia

The United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia is one of two United States district courts serving the Commonwealth of Virginia...

, and Van Buren became Vice President.

Nullification Crisis

The Nullification Crisis was a sectional crisis during the presidency of Andrew Jackson created by South Carolina's 1832 Ordinance of Nullification. This ordinance declared by the power of the State that the federal Tariff of 1828 and 1832 were unconstitutional and therefore null and void within...

had been ongoing since 1828, and in December 1832, Jackson came down squarely against "the nullifiers" in his proclamation. However, in the presidential election of 1832, Jackson confirmed his power in the South by winning his re-election. Jackson had skillfully neutralized Barbour's movement, and Clay did not even appear on several southern tickets. It was only in Calhoun's stronghold of South Carolina that Jackson did not fare well: they put all their electoral votes (11) for Floyd, their ally, for President of the United States.

Floyd's biographer commented that despite advocating moderation in his annual message in December 1832, he was "secretly counting the costs and horrors of war" and that Floyd characterized Jackson's Proclamation in response to South Carolina's Nullification Ordinance as an "outrage upon our institutions" and a "satire upon the revolution" making war inevitable. A letter to Tazewell at this time called Jackson the "tyrant usurper" and feared a civil war would be the result. When Floyd learned that Clay was willing to compromise on the tariff and that South Carolina would submit her issues to a "convention of the states", he supported both. The crisis averted, he toned down his opposition to Jackson, but was unwilling to return to the Democratic Party while Van Buren was the leader. As a result, he turned to Clay, and attempted to bring him and John C. Calhoun

John C. Calhoun

John Caldwell Calhoun was a leading politician and political theorist from South Carolina during the first half of the 19th century. Calhoun eloquently spoke out on every issue of his day, but often changed positions. Calhoun began his political career as a nationalist, modernizer, and proponent...

together in a new political party to support these views. "... the elimination of both Clay and Calhoun from the list of eligibles for the presidency had become temporarily imperative. Accordingly Floyd set himself to the task of working out a fighting alliance between all the factions opposed to the administration. To this end he encouraged discord within the Democratic party, while scrupulously keeping the conflicting ambitions of his own friends in the background." This was the beginnings of the Whig Party

Whig Party (United States)

The Whig Party was a political party of the United States during the era of Jacksonian democracy. Considered integral to the Second Party System and operating from the early 1830s to the mid-1850s, the party was formed in opposition to the policies of President Andrew Jackson and his Democratic...

.

Floyd suffered a stroke in 1834 while still in office, but was able to serve out his term. He approached Littleton Waller Tazewell to be his successor, who was ultimately successful. "Believing that 'great events are in the gale' he urged Tazewell to hasten to Richmond and to be prepared to lay down his share in the power of the state as he had it down for the 'Confederacy,' 'uninjured and undiminished. On April 16, 1834, he left Richmond for his home, escorted by Bigger's Blues, Richardson's Artillery, Myer's Cavalry, and Richardson's Riflemen, Richmond's volunteer companies.

Catholicism and death

In 1832, Floyd's daughter, Mrs Letitia Floyd Lewis, converted to Catholicism, and "owing to her prominence, caused a sensation throughout the state" of Virginia. Then followed other family members, including Floyd himself after he left office as governor. "The conversion of the Floyd and Johnston families led into the Catholic Church other members of the most distinguished families of the South".Floyd suffered a stroke and died on August 17, 1837, in Sweet Springs

Sweet Springs, West Virginia

Sweet Springs is an unincorporated town in Monroe County in the U.S. state of West Virginia. Sweet Springs lies at the intersection of West Virginia Route 3 and West Virginia Route 311. The community is known for its Old Sweet Springs resort and spa, listed on the National Register of Historic Places...

in Monroe County, Virginia

Monroe County, West Virginia

As of the census of 2000, there were 14,583 people, 5,447 households, and 3,883 families residing in the county. The population density was 31 people per square mile . There were 7,267 housing units at an average density of 15 per square mile...

(now West Virginia

West Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian and Southeastern regions of the United States, bordered by Virginia to the southeast, Kentucky to the southwest, Ohio to the northwest, Pennsylvania to the northeast and Maryland to the east...

), and his tombstone can be found in the Lewis Family Cemetery, on the hill behind the remains of the historic Lynnside Manor

Lynnside Historic District

Lynnside Historic District is a national historic district located near Sweet Springs, Monroe County, West Virginia. The district includes six contributing buildings, three contributing sites, and two contributing structures...

. His grave is near to that of John Lewis.

On January 15, 1831, the General Assembly of Virginia passed an act creating the present county of Floyd

Floyd County, Virginia

As of the census of 2000, there were 13,874 people, 5,791 households, and 4,157 families residing in the county. The population density was 36 people per square mile . There were 6,763 housing units at an average density of 18 per square mile...

out of Montgomery County

Montgomery County, Virginia

As of the census of 2000, there were 83,629 people, 30,997 households, and 17,203 families residing in the county. The population density was 215 people per square mile . There were 32,527 housing units at an average density of 84 per square mile...

, named after Floyd, who was governor at the time.

External links

- Governor John Floyd's Grave Virginia Historical Marker

- A Guide to the Executive Papers of Governor John Floyd, 1830-1834 at The Library of Virginia