German Eastern Marches Society

Encyclopedia

German Eastern Marches Society was a German radical

, extremely nationalist

xenophobic

organization founded in 1894. Mainly among Poles, it was sometimes known acronymically

as Hakata or H-K-T after its founders von Hansemann

, Kennemann

and von Tiedemann

. Its main aims were the promotion of Germanization of Poles living in Prussia

and destruction of Polish national identity

in German eastern provinces. Contrary to many similar nationalist organizations created in that period, the Ostmarkenverein had relatively close ties with the government and local administration, which made it largely successful, even though it opposed both the policy of seeking some modo vivendi

with the Poles pursued by Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg and Leo von Caprivi

's policies of relaxation of anti-Polish measures. While of limited significance and often overrated, the organization formed a notable part of German anti-democratic pluralist part of the political landscape of the Wilhelmine

era.

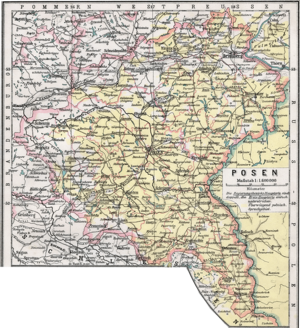

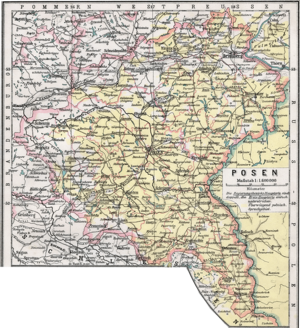

Initially formed in Posen

, in 1896 its main headquarters was moved to Berlin

. In 1901 it had roughly 21,000 members, the number rose to 48,000 in 1913, though some authors claim the membership was as high as 220,000. After Poland was re-established following World War I

in 1918, the society continued its rump activities in the Weimar Republic

until it was closed down by the Nazis in 1934 who created the new organisation with similar activity Bund Deutscher Osten

.

Following the Partitions of Poland

Following the Partitions of Poland

in late 18th century, a large part of the former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

(namely the regions of Greater Poland

, Upper Silesia

and Royal

, the later West Prussia

) was annexed by the Kingdom of Prussia

, the predecessor of the German Empire

, which was formed in 1871. Primarily inhabited by Poles, Greater Poland initially was formed into a semi-autonomous Grand Duchy of Posen, granted with a certain level of self-governance. However, under Otto von Bismarck

's government, the ethnic and cultural tensions in the region began to rise. This was paired by growing tendencies of nationalism

, imperialism

, and chauvinism

within the German society. The tendencies went in two different directions, but were linked to each other. On one hand, a new world order was demanded with desires of creating a German colonial empire

. And on the other, feelings of hostility towards other national groups within the German state were growing.

The situation was further aggravated by Bismarck's policies of Kulturkampf

that in Posen Province took on a much more nationalistic character than in other parts of Germany and included a number of specifically anti-Polish laws that resulted in the Polish and German communities living in a virtual apartheid. Many observers believed these policies only further stoked the Polish independence movement. There is also a question regarding possible personal antipathy towards Poles behind Bismarck's motivation in pursuing the Kulturkampf. Unlike in other parts of the German Empire

, in Greater Poland—then known under the German name of Provinz Posen—the Kulturkampf did not cease after the end of the decade. Although Bismarck finally signed an informal alliance with the Catholic Church against the socialists, the policies of Germanization did continue in Polish-inhabited parts of the country. However, with the end of von Bismarck's rule and the advent of Leo von Caprivi

, the pressure for Germanisation was lessened and many German landowners feared that this would lead to lessening the German control over the Polish areas and in the end deprive Germany of what they saw as a natural reservoir of workforce and land. Although the actual extent of von Caprivi's concessions towards the Poles was very limited, the German minority of Greater Poland feared that this was a step too far, and that von Caprivi's government would cede the power in Greater Poland to the Polish clergy and nobility. The Hakata slogan was: "You are standing opposite to the most dangerous, fanatic enemy of German existence, German honour and German reputation in the world: The Poles."

, German Navy League

, Colonial Society, German Anti-Semitic Organization, and the Defence League. Many landowners feared that their interests would not be properly represented by those organizations and decided to form their own society. It was officially launched November 3, 1894 in Poznań

, then referred to under its German name of Posen. The opening meeting elected an assembly and a general committee composed of 227 members, among them 104 from the Province of Posen

and Province of West Prussia, and additional 113 from other parts of German Empire

. The social base of the newly-founded society was wide and included a large spectrum of people. Some 60% of the representatives of areas of Germany primarily inhabited by Poles were the Junker

s, the landed aristocracy, mostly with ancient feudal roots

. The rest were all groups of middle class Germans, that is civil servants (30%), teachers (25%), merchants, craftsmen, Protestant priests, and clerks.

The official aims of the society was "strengthening and rallying of Germandom in the Eastern Marches through the revival and consolidation of German national feeling and the economic strengthening of the German people" in the area. This was seen as justified due to alleged passivity of Germans in the eastern territories. Officially it was to work for the Germans rather than against the Poles. However, in reality the aims of the society were anti-Polish and aimed at ousting the Polish landowners and peasants from their land at all cost. It was argued that the Poles were an insidious threat to German national and cultural integrity and domination in the east. The propagandistic

rationale behind formation of the H-K-T was presented as a national Polish-German struggle to assimilate one group into the other. It was argued that either the Poles would be successfully Germanized, or the Germans living in the east would face the Polonization themselves. This conflict was often portrayed as a constant biological struggle between the "eastern barbarity" and "European culture". To counter the alleged threat, the Society promoted the destruction of Polish national identity in the Polish lands held by Germany, and prevention of polonization

of the Eastern Marches, that is the growing national sentiment amongst local Poles paired with migration of Poles from rural areas to the cities of the region.

In accordance with the views of Chancellor von Bismarck himself, the Society saw the language question as a key factor in determining one's loyalty towards the state. Because of this view, it insisted on extending the ban on usage of the Polish language

in schools, to other instances of everyday life, including public meetings, books, and newspapers. During a 1902 meeting in Danzig (modern Gdańsk), the Society demanded from the government that the Polish language be banned even from voluntary classes in schools and universities, that the language be banned from public usage and that the Polish language newspapers be either liquidated or forced to be printed in bilingual versions.

With limited local success and support, the Ostmarkenverein functioned primarily as a nationwide propaganda

and pressure group. Its press organ, the Die Ostmark (Eastern March) was one of the primary sources of information on the Polish Question for the German public and shaped the national-conservative views towards the ethnic conflict in the eastern territories of Germany. The Society also opened a number of libraries in the Polish-dominated areas, where it supported the literary production of books and novels promoting an aggressive stance against the Poles. The popular Ostmarkenromane(Ostmark novels) depicted Poles as non-white and struggled to portray a two race dichtomy between "black" Poles and "white" Germans

However, it did not limit itself to mere cultural struggle for domination but also promoted a physical removal of the Poles from their lands in order to make space for the German colonization. The pressure of the H-K-T indeed made the government of von Caprivi

adopt a firmer stance against the Poles. The ban on Polish schools was reintroduced and all teaching was to be done in German language

. The ban was also used by the German police to harass the Polish trade union

movement as they interpreted all public meetings as educational undertakings.

An important issue was the colonisation of Polish territory: the organisation actively supported the nationalist policy of Germanisation

through removal of Polish population and promoting settlement of ethnic Germans in the eastern regions of the German Empire

. It was among the main supporters of creation of the Settlement Commission

, an official authority with a fund to buy up the land from the Poles and redistribute it among German settlers. Since 1905 the organisation also proposed and lobbied for a law that would allow forced eviction of Polish owners of land, and succeed in 1908 when the law was eventually passed. However, it remained on paper in the following years, to which the H-K-T responded with large scale propaganda campaign in the press. The campaign proved to be successful and on October 12, 1912 the Prussian government issued a decision allowing eviction of Polish property owners in Greater Poland.

s, it was one of the groups to oppose the Society's goals the most. Initially treated with reserve by most of the conservative Prussian aristocracy, with time it became actively opposed by many of them. The Society opposed any immigration of Poles from the Russian Poland

to the area, while the Junkers gained large profits from seasoned workers migrating there every year, mostly from other parts of Poland. Also the German colonists brought to formerly Polish lands by the Settlement Commission

or the German government largely benefited from the cooperation with their Polish neighbours and mostly either ignored the Hakatisten or even actively opposed their ideas. This made the Ostmarkenverein an organization formed mostly by the German bourgeoisie

and settlers, that is middle class

members of the local administration, and not the Prussian Junkers. Other notable group of supporters included the local artisans and businessmen, whose interests were endangered by the organic work

, that is the Polish response to the economical competition promoted by the Settlement Commission

and other similar organizations. In a sample probe of H-K-T's members, the social classes represented were as follows:

. In addition, the main opposition centre on the Polish side became the middle class rather than aristocracy, which strengthened the Polish resistance and intensified the national sentiment within the Polish society. Also, the pressure from the German nationalists

resulted in strengthening the Polish national-democrats, particularly the Polish National-Democratic Party of Roman Dmowski

and Wojciech Korfanty

.

For instance, the Settlement Commission throughout the 27 years of its existence managed to plant about 25,000 German families on 1,240 km² (479 mi²) of land in Greater Poland and Pomerania. However, at the same time the reaction of Polish societies resulted in about 35,000 new Polish farmers being settled in the area of roughly 1,500 km² (579 mi²) of land. Similarly, the attempts at banning the teaching of religion in Polish language met with a nationwide resistance and several school strikes that sparked a campaign in foreign media.

the nationalisms on both sides ran high and the liberal politicians who were seeking some compromise with the German Empire were seen as traitors, while German politicians trying to tone down the aggressive rhetoric on both sides were under attack from the Hakatisten. This situation proved vital to the failure of German plans of creation of Mitteleuropa

during the Great War, as the Polish political scene was taken over mostly by politicians hostile to Germany.

to use the threat of reprisals against the remaining Polish minority in Germany in order to win further concessions for the German minority in Poland. However, the post-war government of Gustav Stresemann

mostly rejected the pleas as there were many more Germans in Poland than Poles in Germany, and such a tit-for-tat tactics would harm the German side more. The Society continued to exist in Berlin, limiting its activities mostly to a press campaign and rhetoric, but its meaning was seriously limited. Finally, after the advent of Adolf Hitler

's rule in Germany, it was disbanded by the Nazis. Some of its former members, now living in Poland, remained members of other German societies and organizations, and formed the core of the German Fifth column

during the German invasion of Poland of 1939.

Extremism

Extremism is any ideology or political act far outside the perceived political center of a society; or otherwise claimed to violate common moral standards...

, extremely nationalist

Nationalism

Nationalism is a political ideology that involves a strong identification of a group of individuals with a political entity defined in national terms, i.e. a nation. In the 'modernist' image of the nation, it is nationalism that creates national identity. There are various definitions for what...

xenophobic

Xenophobia

Xenophobia is defined as "an unreasonable fear of foreigners or strangers or of that which is foreign or strange". It comes from the Greek words ξένος , meaning "stranger," "foreigner" and φόβος , meaning "fear."...

organization founded in 1894. Mainly among Poles, it was sometimes known acronymically

Acronym and initialism

Acronyms and initialisms are abbreviations formed from the initial components in a phrase or a word. These components may be individual letters or parts of words . There is no universal agreement on the precise definition of the various terms , nor on written usage...

as Hakata or H-K-T after its founders von Hansemann

Ferdinand von Hansemann

Ferdinand von Hansemann was a Prussian landlord and politician, co-founder of the German Eastern Marches Society.Hansemann was born to Adolf von Hansemann, a notable Prussian industrialist and manager of the Disconto Society , a large financial holding. Since early youth Hansemann was a member of...

, Kennemann

Hermann Kennemann

Hermann Kennemann-Klenka was a Prussian politician and landowner, co-founder of the German Eastern Marches Society. He was notable as one of the main supporters of Germanization of Polish lands then ruled by German Empire....

and von Tiedemann

Heinrich von Tiedemann

Heinrich von Tiedemann was a Prussian politician, co-founder of the German Eastern Marches Society .Tiedemann was born in Dembogorsch , he died in Berlin.- References :...

. Its main aims were the promotion of Germanization of Poles living in Prussia

Prussia

Prussia was a German kingdom and historic state originating out of the Duchy of Prussia and the Margraviate of Brandenburg. For centuries, the House of Hohenzollern ruled Prussia, successfully expanding its size by way of an unusually well-organized and effective army. Prussia shaped the history...

and destruction of Polish national identity

National identity

National identity is the person's identity and sense of belonging to one state or to one nation, a feeling one shares with a group of people, regardless of one's citizenship status....

in German eastern provinces. Contrary to many similar nationalist organizations created in that period, the Ostmarkenverein had relatively close ties with the government and local administration, which made it largely successful, even though it opposed both the policy of seeking some modo vivendi

Modus vivendi

Modus vivendi is a Latin phrase signifying an agreement between those whose opinions differ, such that they agree to disagree.Modus means mode, way. Vivendi means of living. Together, way of living, implies an accommodation between disputing parties to allow life to go on. It usually describes...

with the Poles pursued by Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg and Leo von Caprivi

Leo von Caprivi

Georg Leo Graf von Caprivi de Caprera de Montecuccoli was a German major general and statesman, who succeeded Otto von Bismarck as Chancellor of Germany...

's policies of relaxation of anti-Polish measures. While of limited significance and often overrated, the organization formed a notable part of German anti-democratic pluralist part of the political landscape of the Wilhelmine

Wilhelmine

Wilhelmine is a term for the period of German history, also known as the German Empire. The term Wilhelmine Germany refers to the period running from the proclamation of Wilhelm I as German Kaiser at Versailles in 1871 to the abdication of his grandson Wilhelm II in 1918.Although the father of...

era.

Initially formed in Posen

Poznan

Poznań is a city on the Warta river in west-central Poland, with a population of 556,022 in June 2009. It is among the oldest cities in Poland, and was one of the most important centres in the early Polish state, whose first rulers were buried at Poznań's cathedral. It is sometimes claimed to be...

, in 1896 its main headquarters was moved to Berlin

Berlin

Berlin is the capital city of Germany and is one of the 16 states of Germany. With a population of 3.45 million people, Berlin is Germany's largest city. It is the second most populous city proper and the seventh most populous urban area in the European Union...

. In 1901 it had roughly 21,000 members, the number rose to 48,000 in 1913, though some authors claim the membership was as high as 220,000. After Poland was re-established following World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

in 1918, the society continued its rump activities in the Weimar Republic

Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic is the name given by historians to the parliamentary republic established in 1919 in Germany to replace the imperial form of government...

until it was closed down by the Nazis in 1934 who created the new organisation with similar activity Bund Deutscher Osten

Bund Deutscher Osten

Bund Deutscher Osten was a German Nazi organisation founded on 26 May 1933. The organisation was supported by the Nazi Party. The BDO was a national socialist version of German Eastern Marches Society, which was closed down by the Nazis in 1934...

.

Background

Partitions of Poland

The Partitions of Poland or Partitions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth took place in the second half of the 18th century and ended the existence of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, resulting in the elimination of sovereign Poland for 123 years...

in late 18th century, a large part of the former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth was a dualistic state of Poland and Lithuania ruled by a common monarch. It was the largest and one of the most populous countries of 16th- and 17th‑century Europe with some and a multi-ethnic population of 11 million at its peak in the early 17th century...

(namely the regions of Greater Poland

Greater Poland

Greater Poland or Great Poland, often known by its Polish name Wielkopolska is a historical region of west-central Poland. Its chief city is Poznań.The boundaries of Greater Poland have varied somewhat throughout history...

, Upper Silesia

Upper Silesia

Upper Silesia is the southeastern part of the historical and geographical region of Silesia. Since the 9th century, Upper Silesia has been part of Greater Moravia, the Duchy of Bohemia, the Piast Kingdom of Poland, again of the Lands of the Bohemian Crown and the Holy Roman Empire, as well as of...

and Royal

Royal Prussia

Royal Prussia was a Region of the Kingdom of Poland and of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth . Polish Prussia included Pomerelia, Chełmno Land , Malbork Voivodeship , Gdańsk , Toruń , and Elbląg . It is distinguished from Ducal Prussia...

, the later West Prussia

West Prussia

West Prussia was a province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1773–1824 and 1878–1919/20 which was created out of the earlier Polish province of Royal Prussia...

) was annexed by the Kingdom of Prussia

Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia was a German kingdom from 1701 to 1918. Until the defeat of Germany in World War I, it comprised almost two-thirds of the area of the German Empire...

, the predecessor of the German Empire

German Empire

The German Empire refers to Germany during the "Second Reich" period from the unification of Germany and proclamation of Wilhelm I as German Emperor on 18 January 1871, to 1918, when it became a federal republic after defeat in World War I and the abdication of the Emperor, Wilhelm II.The German...

, which was formed in 1871. Primarily inhabited by Poles, Greater Poland initially was formed into a semi-autonomous Grand Duchy of Posen, granted with a certain level of self-governance. However, under Otto von Bismarck

Otto von Bismarck

Otto Eduard Leopold, Prince of Bismarck, Duke of Lauenburg , simply known as Otto von Bismarck, was a Prussian-German statesman whose actions unified Germany, made it a major player in world affairs, and created a balance of power that kept Europe at peace after 1871.As Minister President of...

's government, the ethnic and cultural tensions in the region began to rise. This was paired by growing tendencies of nationalism

Nationalism

Nationalism is a political ideology that involves a strong identification of a group of individuals with a political entity defined in national terms, i.e. a nation. In the 'modernist' image of the nation, it is nationalism that creates national identity. There are various definitions for what...

, imperialism

Imperialism

Imperialism, as defined by Dictionary of Human Geography, is "the creation and/or maintenance of an unequal economic, cultural, and territorial relationships, usually between states and often in the form of an empire, based on domination and subordination." The imperialism of the last 500 years,...

, and chauvinism

Chauvinism

Chauvinism, in its original and primary meaning, is an exaggerated, bellicose patriotism and a belief in national superiority and glory. It is an eponym of a possibly fictional French soldier Nicolas Chauvin who was credited with many superhuman feats in the Napoleonic wars.By extension it has come...

within the German society. The tendencies went in two different directions, but were linked to each other. On one hand, a new world order was demanded with desires of creating a German colonial empire

Colonialism

Colonialism is the establishment, maintenance, acquisition and expansion of colonies in one territory by people from another territory. It is a process whereby the metropole claims sovereignty over the colony and the social structure, government, and economics of the colony are changed by...

. And on the other, feelings of hostility towards other national groups within the German state were growing.

The situation was further aggravated by Bismarck's policies of Kulturkampf

Kulturkampf

The German term refers to German policies in relation to secularity and the influence of the Roman Catholic Church, enacted from 1871 to 1878 by the Prime Minister of Prussia, Otto von Bismarck. The Kulturkampf did not extend to the other German states such as Bavaria...

that in Posen Province took on a much more nationalistic character than in other parts of Germany and included a number of specifically anti-Polish laws that resulted in the Polish and German communities living in a virtual apartheid. Many observers believed these policies only further stoked the Polish independence movement. There is also a question regarding possible personal antipathy towards Poles behind Bismarck's motivation in pursuing the Kulturkampf. Unlike in other parts of the German Empire

German Empire

The German Empire refers to Germany during the "Second Reich" period from the unification of Germany and proclamation of Wilhelm I as German Emperor on 18 January 1871, to 1918, when it became a federal republic after defeat in World War I and the abdication of the Emperor, Wilhelm II.The German...

, in Greater Poland—then known under the German name of Provinz Posen—the Kulturkampf did not cease after the end of the decade. Although Bismarck finally signed an informal alliance with the Catholic Church against the socialists, the policies of Germanization did continue in Polish-inhabited parts of the country. However, with the end of von Bismarck's rule and the advent of Leo von Caprivi

Leo von Caprivi

Georg Leo Graf von Caprivi de Caprera de Montecuccoli was a German major general and statesman, who succeeded Otto von Bismarck as Chancellor of Germany...

, the pressure for Germanisation was lessened and many German landowners feared that this would lead to lessening the German control over the Polish areas and in the end deprive Germany of what they saw as a natural reservoir of workforce and land. Although the actual extent of von Caprivi's concessions towards the Poles was very limited, the German minority of Greater Poland feared that this was a step too far, and that von Caprivi's government would cede the power in Greater Poland to the Polish clergy and nobility. The Hakata slogan was: "You are standing opposite to the most dangerous, fanatic enemy of German existence, German honour and German reputation in the world: The Poles."

The Society

Under such circumstances a number of nationalist organizations and pressure groups was formed, all collectively known as the nationale Verbände. Among them were the Pan-German LeaguePan-German League

The Pan-German League was an extremist, ultra-nationalist political interest organization which was officially founded in 1891, a year after the Zanzibar Treaty was signed. It was concerned with a host of issues, concentrating on imperialism, anti-semitism, the so called Polish Question, and...

, German Navy League

Navy League (Germany)

The Navy League or Fleet Association in Imperial Germany was an interest group formed on April 30 1898 on initiative of Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz through the German Imperial Naval Office which he headed to support the expansion of the Imperial Navy ...

, Colonial Society, German Anti-Semitic Organization, and the Defence League. Many landowners feared that their interests would not be properly represented by those organizations and decided to form their own society. It was officially launched November 3, 1894 in Poznań

Poznan

Poznań is a city on the Warta river in west-central Poland, with a population of 556,022 in June 2009. It is among the oldest cities in Poland, and was one of the most important centres in the early Polish state, whose first rulers were buried at Poznań's cathedral. It is sometimes claimed to be...

, then referred to under its German name of Posen. The opening meeting elected an assembly and a general committee composed of 227 members, among them 104 from the Province of Posen

Province of Posen

The Province of Posen was a province of Prussia from 1848–1918 and as such part of the German Empire from 1871 to 1918. The area was about 29,000 km2....

and Province of West Prussia, and additional 113 from other parts of German Empire

German Empire

The German Empire refers to Germany during the "Second Reich" period from the unification of Germany and proclamation of Wilhelm I as German Emperor on 18 January 1871, to 1918, when it became a federal republic after defeat in World War I and the abdication of the Emperor, Wilhelm II.The German...

. The social base of the newly-founded society was wide and included a large spectrum of people. Some 60% of the representatives of areas of Germany primarily inhabited by Poles were the Junker

Junker

A Junker was a member of the landed nobility of Prussia and eastern Germany. These families were mostly part of the German Uradel and carried on the colonization and Christianization of the northeastern European territories during the medieval Ostsiedlung. The abbreviation of Junker is Jkr...

s, the landed aristocracy, mostly with ancient feudal roots

Uradel

The German and Scandinavian term Uradel refers to nobility who can trace back their noble ancestry at least to the year 1400 and probably originates from leadership positions during the Migration Period.-Divisions of German nobility:Uradel : Nobility that originates from leadership positions held...

. The rest were all groups of middle class Germans, that is civil servants (30%), teachers (25%), merchants, craftsmen, Protestant priests, and clerks.

The official aims of the society was "strengthening and rallying of Germandom in the Eastern Marches through the revival and consolidation of German national feeling and the economic strengthening of the German people" in the area. This was seen as justified due to alleged passivity of Germans in the eastern territories. Officially it was to work for the Germans rather than against the Poles. However, in reality the aims of the society were anti-Polish and aimed at ousting the Polish landowners and peasants from their land at all cost. It was argued that the Poles were an insidious threat to German national and cultural integrity and domination in the east. The propagandistic

Propaganda

Propaganda is a form of communication that is aimed at influencing the attitude of a community toward some cause or position so as to benefit oneself or one's group....

rationale behind formation of the H-K-T was presented as a national Polish-German struggle to assimilate one group into the other. It was argued that either the Poles would be successfully Germanized, or the Germans living in the east would face the Polonization themselves. This conflict was often portrayed as a constant biological struggle between the "eastern barbarity" and "European culture". To counter the alleged threat, the Society promoted the destruction of Polish national identity in the Polish lands held by Germany, and prevention of polonization

Polonization

Polonization was the acquisition or imposition of elements of Polish culture, in particular, Polish language, as experienced in some historic periods by non-Polish populations of territories controlled or substantially influenced by Poland...

of the Eastern Marches, that is the growing national sentiment amongst local Poles paired with migration of Poles from rural areas to the cities of the region.

In accordance with the views of Chancellor von Bismarck himself, the Society saw the language question as a key factor in determining one's loyalty towards the state. Because of this view, it insisted on extending the ban on usage of the Polish language

Polish language

Polish is a language of the Lechitic subgroup of West Slavic languages, used throughout Poland and by Polish minorities in other countries...

in schools, to other instances of everyday life, including public meetings, books, and newspapers. During a 1902 meeting in Danzig (modern Gdańsk), the Society demanded from the government that the Polish language be banned even from voluntary classes in schools and universities, that the language be banned from public usage and that the Polish language newspapers be either liquidated or forced to be printed in bilingual versions.

With limited local success and support, the Ostmarkenverein functioned primarily as a nationwide propaganda

Propaganda

Propaganda is a form of communication that is aimed at influencing the attitude of a community toward some cause or position so as to benefit oneself or one's group....

and pressure group. Its press organ, the Die Ostmark (Eastern March) was one of the primary sources of information on the Polish Question for the German public and shaped the national-conservative views towards the ethnic conflict in the eastern territories of Germany. The Society also opened a number of libraries in the Polish-dominated areas, where it supported the literary production of books and novels promoting an aggressive stance against the Poles. The popular Ostmarkenromane(Ostmark novels) depicted Poles as non-white and struggled to portray a two race dichtomy between "black" Poles and "white" Germans

However, it did not limit itself to mere cultural struggle for domination but also promoted a physical removal of the Poles from their lands in order to make space for the German colonization. The pressure of the H-K-T indeed made the government of von Caprivi

Leo von Caprivi

Georg Leo Graf von Caprivi de Caprera de Montecuccoli was a German major general and statesman, who succeeded Otto von Bismarck as Chancellor of Germany...

adopt a firmer stance against the Poles. The ban on Polish schools was reintroduced and all teaching was to be done in German language

German language

German is a West Germanic language, related to and classified alongside English and Dutch. With an estimated 90 – 98 million native speakers, German is one of the world's major languages and is the most widely-spoken first language in the European Union....

. The ban was also used by the German police to harass the Polish trade union

Trade union

A trade union, trades union or labor union is an organization of workers that have banded together to achieve common goals such as better working conditions. The trade union, through its leadership, bargains with the employer on behalf of union members and negotiates labour contracts with...

movement as they interpreted all public meetings as educational undertakings.

An important issue was the colonisation of Polish territory: the organisation actively supported the nationalist policy of Germanisation

Germanisation

Germanisation is both the spread of the German language, people and culture either by force or assimilation, and the adaptation of a foreign word to the German language in linguistics, much like the Romanisation of many languages which do not use the Latin alphabet...

through removal of Polish population and promoting settlement of ethnic Germans in the eastern regions of the German Empire

German Empire

The German Empire refers to Germany during the "Second Reich" period from the unification of Germany and proclamation of Wilhelm I as German Emperor on 18 January 1871, to 1918, when it became a federal republic after defeat in World War I and the abdication of the Emperor, Wilhelm II.The German...

. It was among the main supporters of creation of the Settlement Commission

Settlement Commission

The Prussian Settlement Commission was a Prussian government commission that operated between 1886 and 1924, but actively only until 1918. It was set up by Otto von Bismarck to increase land ownership by Germans at the expense of Poles, by economic and political means, in the German Empire's...

, an official authority with a fund to buy up the land from the Poles and redistribute it among German settlers. Since 1905 the organisation also proposed and lobbied for a law that would allow forced eviction of Polish owners of land, and succeed in 1908 when the law was eventually passed. However, it remained on paper in the following years, to which the H-K-T responded with large scale propaganda campaign in the press. The campaign proved to be successful and on October 12, 1912 the Prussian government issued a decision allowing eviction of Polish property owners in Greater Poland.

Social base

Interestingly, although the H-K-T is to this day primarily associated with the JunkerJunker

A Junker was a member of the landed nobility of Prussia and eastern Germany. These families were mostly part of the German Uradel and carried on the colonization and Christianization of the northeastern European territories during the medieval Ostsiedlung. The abbreviation of Junker is Jkr...

s, it was one of the groups to oppose the Society's goals the most. Initially treated with reserve by most of the conservative Prussian aristocracy, with time it became actively opposed by many of them. The Society opposed any immigration of Poles from the Russian Poland

Congress Poland

The Kingdom of Poland , informally known as Congress Poland , created in 1815 by the Congress of Vienna, was a personal union of the Russian parcel of Poland with the Russian Empire...

to the area, while the Junkers gained large profits from seasoned workers migrating there every year, mostly from other parts of Poland. Also the German colonists brought to formerly Polish lands by the Settlement Commission

Settlement Commission

The Prussian Settlement Commission was a Prussian government commission that operated between 1886 and 1924, but actively only until 1918. It was set up by Otto von Bismarck to increase land ownership by Germans at the expense of Poles, by economic and political means, in the German Empire's...

or the German government largely benefited from the cooperation with their Polish neighbours and mostly either ignored the Hakatisten or even actively opposed their ideas. This made the Ostmarkenverein an organization formed mostly by the German bourgeoisie

Bourgeoisie

In sociology and political science, bourgeoisie describes a range of groups across history. In the Western world, between the late 18th century and the present day, the bourgeoisie is a social class "characterized by their ownership of capital and their related culture." A member of the...

and settlers, that is middle class

Middle class

The middle class is any class of people in the middle of a societal hierarchy. In Weberian socio-economic terms, the middle class is the broad group of people in contemporary society who fall socio-economically between the working class and upper class....

members of the local administration, and not the Prussian Junkers. Other notable group of supporters included the local artisans and businessmen, whose interests were endangered by the organic work

Organic work

Organic work is a term coined by 19th century Polish positivists, denoting an ideology demanding that the vital powers of the nation be spent on labour rather than fruitless national uprisings. The basic principles of the organic work included education of the masses and increase of the economical...

, that is the Polish response to the economical competition promoted by the Settlement Commission

Settlement Commission

The Prussian Settlement Commission was a Prussian government commission that operated between 1886 and 1924, but actively only until 1918. It was set up by Otto von Bismarck to increase land ownership by Germans at the expense of Poles, by economic and political means, in the German Empire's...

and other similar organizations. In a sample probe of H-K-T's members, the social classes represented were as follows:

- 26.6% of civil servants and members of German administration

- 17.6% of artisans

- 15.7% of businessmen

- 14.0% of teachers

- 10.7% of landowners

- 4.2% of clergymen

- 2.7% of army officers

- 0.7% of rentiers

- 6.5% of other professions

- 1.3% of people with no designation

In Poland

By 1913 the Society had roughly 48,000 members. Despite its fierce rhetoric, support from the local administration and certain popularity of its goals, the Society proved to be largely unsuccessful as were the projects it promoted. Much like other similar organizations, the H-K-T not only managed to incite some public awareness to the Polish Question within German public and radicalise the German policies in the area, but also sparked a Polish reaction. As an effect of the external pressure, the Poles living in the German Empire started to organize themselves in order to prevent the plans of GermanisationGermanisation

Germanisation is both the spread of the German language, people and culture either by force or assimilation, and the adaptation of a foreign word to the German language in linguistics, much like the Romanisation of many languages which do not use the Latin alphabet...

. In addition, the main opposition centre on the Polish side became the middle class rather than aristocracy, which strengthened the Polish resistance and intensified the national sentiment within the Polish society. Also, the pressure from the German nationalists

Nationalism

Nationalism is a political ideology that involves a strong identification of a group of individuals with a political entity defined in national terms, i.e. a nation. In the 'modernist' image of the nation, it is nationalism that creates national identity. There are various definitions for what...

resulted in strengthening the Polish national-democrats, particularly the Polish National-Democratic Party of Roman Dmowski

Roman Dmowski

Roman Stanisław Dmowski was a Polish politician, statesman, and chief ideologue and co-founder of the National Democracy political movement, which was one of the strongest political camps of interwar Poland.Though a controversial personality throughout his life, Dmowski was instrumental in...

and Wojciech Korfanty

Wojciech Korfanty

Wojciech Korfanty , born Adalbert Korfanty, was a Polish nationalist activist, journalist and politician, serving as member of the German parliaments Reichstag and Prussian Landtag, and later on, in the Polish Sejm...

.

For instance, the Settlement Commission throughout the 27 years of its existence managed to plant about 25,000 German families on 1,240 km² (479 mi²) of land in Greater Poland and Pomerania. However, at the same time the reaction of Polish societies resulted in about 35,000 new Polish farmers being settled in the area of roughly 1,500 km² (579 mi²) of land. Similarly, the attempts at banning the teaching of religion in Polish language met with a nationwide resistance and several school strikes that sparked a campaign in foreign media.

In Germany

All in all, even though the H-K-T Society was not the most influential and its exact influence on the German governments is disputable, it was among the best-heard and for the Polish people became one of the symbols of oppression, chauvinism, and national discrimination, thus poisoning the Polish-German relations both in the borderland and in entire Germany. On the eve of World War IWorld War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

the nationalisms on both sides ran high and the liberal politicians who were seeking some compromise with the German Empire were seen as traitors, while German politicians trying to tone down the aggressive rhetoric on both sides were under attack from the Hakatisten. This situation proved vital to the failure of German plans of creation of Mitteleuropa

Mitteleuropa

Mitteleuropa is the German term equal to Central Europe. The word has political, geographic and cultural meaning. While it describes a geographical location, it also is the word denoting a political concept of a German-dominated and exploited Central European union that was put into motion during...

during the Great War, as the Polish political scene was taken over mostly by politicians hostile to Germany.

Post-war organisation

The works of the Ostmarkenverein practically ceased during the war. At its end, some of its members joined the Deutsche Vereinigung (German Association), a society that aimed at preventing newly-restored Poland from acquiring the lands that were formerly in Prussia. Many more of its members feared possible Polish reprisals after the take-over of Greater Poland, Pomerania and Silesia, and were among the first to pack their belongings and head westwards after the armistice, while others stayed in the lands that were taken over by Poland, protected by the Minority Treaty. Even though the Ostmarkenverein had lost its main rationale as Germany had no influence over the lands of the Republic of Poland, it continued to exist in a rump form. Headed from Berlin, it tried to force the government of the Weimar RepublicWeimar Republic

The Weimar Republic is the name given by historians to the parliamentary republic established in 1919 in Germany to replace the imperial form of government...

to use the threat of reprisals against the remaining Polish minority in Germany in order to win further concessions for the German minority in Poland. However, the post-war government of Gustav Stresemann

Gustav Stresemann

was a German politician and statesman who served as Chancellor and Foreign Minister during the Weimar Republic. He was co-laureate of the Nobel Peace Prize in 1926.Stresemann's politics defy easy categorization...

mostly rejected the pleas as there were many more Germans in Poland than Poles in Germany, and such a tit-for-tat tactics would harm the German side more. The Society continued to exist in Berlin, limiting its activities mostly to a press campaign and rhetoric, but its meaning was seriously limited. Finally, after the advent of Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler was an Austrian-born German politician and the leader of the National Socialist German Workers Party , commonly referred to as the Nazi Party). He was Chancellor of Germany from 1933 to 1945, and head of state from 1934 to 1945...

's rule in Germany, it was disbanded by the Nazis. Some of its former members, now living in Poland, remained members of other German societies and organizations, and formed the core of the German Fifth column

Fifth column

A fifth column is a group of people who clandestinely undermine a larger group such as a nation from within.-Origin:The term originated with a 1936 radio address by Emilio Mola, a Nationalist General during the 1936–39 Spanish Civil War...

during the German invasion of Poland of 1939.