Dziga Vertov

Encyclopedia

Pseudonym

A pseudonym is a name that a person assumes for a particular purpose and that differs from his or her original orthonym...

Dziga Vertov , was a Soviet

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

pioneer documentary film

Documentary film

Documentary films constitute a broad category of nonfictional motion pictures intended to document some aspect of reality, primarily for the purposes of instruction or maintaining a historical record...

, newsreel

Newsreel

A newsreel was a form of short documentary film prevalent in the first half of the 20th century, regularly released in a public presentation place and containing filmed news stories and items of topical interest. It was a source of news, current affairs and entertainment for millions of moviegoers...

director and cinema theorist. His filming practices and theories influenced the Cinéma vérité

Cinéma vérité

Cinéma vérité is a style of documentary filmmaking, combining naturalistic techniques with stylized cinematic devices of editing and camerawork, staged set-ups, and the use of the camera to provoke subjects. It is also known for taking a provocative stance toward its topics.There are subtle yet...

style of documentary moviemaking and, in particular the Dziga Vertov Group

Dziga Vertov Group

The Dziga Vertov Group was formed in 1968 by politically active filmmakers including Jean-Luc Godard and Jean-Pierre Gorin. Their films are defined primarily for Brechtian forms, Marxist ideology, and a lack of personal authorship...

active in the 1960s.

Early years

Born David Abelevich Kaufman into a family of Jewish intellectuals in Białystok, Congress PolandCongress Poland

The Kingdom of Poland , informally known as Congress Poland , created in 1815 by the Congress of Vienna, was a personal union of the Russian parcel of Poland with the Russian Empire...

, then a part of the Russian Empire

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was a state that existed from 1721 until the Russian Revolution of 1917. It was the successor to the Tsardom of Russia and the predecessor of the Soviet Union...

. His father was a librarian. He Russified

Russification

Russification is an adoption of the Russian language or some other Russian attributes by non-Russian communities...

his Jewish name David and patronymic

Patronymic

A patronym, or patronymic, is a component of a personal name based on the name of one's father, grandfather or an even earlier male ancestor. A component of a name based on the name of one's mother or a female ancestor is a matronymic. Each is a means of conveying lineage.In many areas patronyms...

Abelevich to Denis Arkadievich at some point after 1918. Kaufman studied music at Białystok Conservatory until his family fled from the invading German army

German Army

The German Army is the land component of the armed forces of the Federal Republic of Germany. Following the disbanding of the Wehrmacht after World War II, it was re-established in 1955 as the Bundesheer, part of the newly formed West German Bundeswehr along with the Navy and the Air Force...

to Moscow

Moscow

Moscow is the capital, the most populous city, and the most populous federal subject of Russia. The city is a major political, economic, cultural, scientific, religious, financial, educational, and transportation centre of Russia and the continent...

in 1915. The Kaufmans soon settled in Petrograd, where Denis Kaufman began writing poetry

Poetry

Poetry is a form of literary art in which language is used for its aesthetic and evocative qualities in addition to, or in lieu of, its apparent meaning...

, science fiction

Science fiction

Science fiction is a genre of fiction dealing with imaginary but more or less plausible content such as future settings, futuristic science and technology, space travel, aliens, and paranormal abilities...

and satire

Satire

Satire is primarily a literary genre or form, although in practice it can also be found in the graphic and performing arts. In satire, vices, follies, abuses, and shortcomings are held up to ridicule, ideally with the intent of shaming individuals, and society itself, into improvement...

. In 1916-1917 Kaufman was studying medicine at the Psychoneurological Institute in Saint Petersburg and experimenting with "sound collages" in his free time. Kaufman adopted the name "Dziga Vertov" (which translates loosely as 'spinning top'); Vertov's political writings and his work on the Kino-Pravda

Kino-Pravda

Kino-Pravda was a newsreel series by Dziga Vertov, Elizaveta Svilova, and Mikhail Kaufman.Working mainly during the 1920s, Vertov promoted the concept of kino-pravda, or film-truth, through his newsreel series. His driving vision was to capture fragments of actuality which, when organized...

newsreel series show a revolutionary romanticism.

Early Writings

Vertov is known for many early writings, mainly while still in school, that focus on the individual versus the perceptive nature of the camera lens, which he was known to call his "second eye".Most of Vertov's early work was unpublished, and few manuscripts remain after the Second World War

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

, though some material survived in later films and documentaries created by Vertov and his brothers, Boris Kaufman

Boris Kaufman

Boris Abelevich Kaufman, A.S.C. was a cinematographer. He was the younger brother of famous filmmakers Dziga Vertov and Mikhail Kaufman....

and Mikhail Kaufman

Mikhail Kaufman

Mikhail Abramovich Kaufman ; ) was a Russian cinematographer and photographer. He was the younger brother of filmmaker Dziga Vertov and the older brother of cinematographer Boris Kaufman....

.

Vertov is also known for quotes on perception, and its ineffability, in relation to the nature of qualia (sensory experiences).

Career after the October Revolution

After the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, at the age of 22, Vertov began editing for Kino-Nedelya , which first came out in June 1918. While working for Kino-Nedelya he met his future wife, the film director and editor, Elizaveta Svilova, who at the time was working as an editor at GoskinoGoskino

Goskino USSR is the abbreviated name for the USSR State Committee for Cinematography in the Soviet Union...

. She began collaborating with Vertov, beginning as his editor but becoming assistant and co-director in subsequent films, such as Man with a Movie Camera (1929), and Three Songs About Lenin (1934).

Mikhail Kalinin

Mikhail Ivanovich Kalinin , known familiarly by Soviet citizens as "Kalinych," was a Bolshevik revolutionary and the nominal head of state of Russia and later of the Soviet Union, from 1919 to 1946...

's agit-train during the ongoing Russian Civil War

Russian Civil War

The Russian Civil War was a multi-party war that occurred within the former Russian Empire after the Russian provisional government collapsed to the Soviets, under the domination of the Bolshevik party. Soviet forces first assumed power in Petrograd The Russian Civil War (1917–1923) was a...

between Communists and counterrevolutionaries

Counterrevolutionary

A counter-revolutionary is anyone who opposes a revolution, particularly those who act after a revolution to try to overturn or reverse it, in full or in part...

. Some of the cars on the agit-trains were equipped with actors for live performances or printing press

Printing press

A printing press is a device for applying pressure to an inked surface resting upon a print medium , thereby transferring the ink...

es; Vertov's had equipment to shoot, develop, edit, and project film. The trains went to battlefronts on agitation-propaganda

Agitprop

Agitprop is derived from agitation and propaganda, and describes stage plays, pamphlets, motion pictures and other art forms with an explicitly political message....

missions intended primarily to bolster the morale of the troops; they were also intended to stir up revolutionary fervor of the masses.

In 1919, Vertov compiled newsreel footage for his documentary Anniversary of the Revolution; in 1921 he compiled History of the Civil War

Russian Civil War

The Russian Civil War was a multi-party war that occurred within the former Russian Empire after the Russian provisional government collapsed to the Soviets, under the domination of the Bolshevik party. Soviet forces first assumed power in Petrograd The Russian Civil War (1917–1923) was a...

. The so-called "Council of Three," a group issuing manifestoes in LEF, a radical Russian newsmagazine, was established in 1922; the group's "three" were Vertov, his (future) wife and editor Elizaveta Svilova, and his brother and cinematographer

Cinematographer

A cinematographer is one photographing with a motion picture camera . The title is generally equivalent to director of photography , used to designate a chief over the camera and lighting crews working on a film, responsible for achieving artistic and technical decisions related to the image...

Mikhail Kaufman

Mikhail Kaufman

Mikhail Abramovich Kaufman ; ) was a Russian cinematographer and photographer. He was the younger brother of filmmaker Dziga Vertov and the older brother of cinematographer Boris Kaufman....

. Vertov's interest in machinery led to a curiosity about the mechanical basis of cinema

Film

A film, also called a movie or motion picture, is a series of still or moving images. It is produced by recording photographic images with cameras, or by creating images using animation techniques or visual effects...

.

Kino-Pravda

In 1922, the year that Nanook of the NorthNanook of the North

Nanook of the North is a 1922 silent documentary film by Robert J. Flaherty. In the tradition of what would later be called salvage ethnography, Flaherty captured the struggles of the Inuk Nanook and his family in the Canadian arctic...

was released, Vertov started the Kino-Pravda

Kino-Pravda

Kino-Pravda was a newsreel series by Dziga Vertov, Elizaveta Svilova, and Mikhail Kaufman.Working mainly during the 1920s, Vertov promoted the concept of kino-pravda, or film-truth, through his newsreel series. His driving vision was to capture fragments of actuality which, when organized...

series. The series took its title from the official government newspaper Pravda

Pravda

Pravda was a leading newspaper of the Soviet Union and an official organ of the Central Committee of the Communist Party between 1912 and 1991....

. "Kino-Pravda" (literally translated, "film truth") continued Vertov's agit-prop bent. "The Kino-Pravda group began its work in a basement in the centre of Moscow" Vertov explained. He called it damp and dark. There was an earthen floor and holes one stumbled into at every turn. Dziga said, " This dampness prevented our reels of lovingly edited film from sticking together properly, rusted our scissors and our splicers." "Before dawn- damp, cold, teeth chattering- I wrap comrade Svilova in a third jacket." [quotation needed]

Vertov's driving vision, expounded in his frequent essays, was to capture "film truth"—that is, fragments of actuality which, when organized together, have a deeper truth that cannot be seen with the naked eye. In the "Kino-Pravda" series, Vertov focused on everyday experiences, eschewing bourgeois concerns and filming marketplaces, bars, and schools instead, sometimes with a hidden camera, without asking permission first. The episodes of "Kino-Pravda" usually did not include reenactments or stagings (one exception is the segment about the trial of the Social Revolutionaries: the scenes of the selling of the newspapers on the streets and the people reading the papers in the trolley were both staged for the camera). The cinematography is simple, functional, unelaborate—perhaps a result of Vertov's disinterest in both "beauty" and the "grandeur of fiction." Twenty-three issues of the series were produced over a period of three years; each issue lasted about twenty minutes and usually covered three topics. The stories were typically descriptive, not narrative, and included vignettes and exposés, showing for instance the renovation of a trolley system, the organization of farmers into communes, and the trial of Social Revolutionaries; one story shows starvation in the nascent Communist

Communism

Communism is a social, political and economic ideology that aims at the establishment of a classless, moneyless, revolutionary and stateless socialist society structured upon common ownership of the means of production...

state. Propagandistic tendencies are also present, but with more subtlety, in the episode featuring the construction of an airport: one shot shows the former Tsar

Tsar

Tsar is a title used to designate certain European Slavic monarchs or supreme rulers. As a system of government in the Tsardom of Russia and Russian Empire, it is known as Tsarist autocracy, or Tsarism...

's tanks helping prepare a foundation, with an intertitle reading "Tanks on the labor front."

Vertov clearly intended an active relationship with his audience in the series—in the final segment he includes contact information—but by the 14th episode the series had become so experimental that some critics dismissed Vertov's efforts as "insane". Vertov responds to their criticisms with the assertion that the critics were hacks nipping "revolutionary effort" in the bud, and concludes the essay with his promise to "explode art's tower of Babel

Tower of Babel

The Tower of Babel , according to the Book of Genesis, was an enormous tower built in the plain of Shinar .According to the biblical account, a united humanity of the generations following the Great Flood, speaking a single language and migrating from the east, came to the land of Shinar, where...

." In Vertov's view, "art's tower of Babel" was the subservience of cinematic technique to narrative, commonly known as the Institutional Mode of Representation

Institutional mode of representation

In film theory, the institutional mode of representation is the dominant mode of film construction, which developed in the years after the turn of the century, becoming the norm by about 1914. Although virtually all films produced today are made within the IMR, it is not the only possible mode of...

.

By this point in his career, Vertov was clearly and emphatically dissatisfied with narrative tradition, and expresses his hostility towards dramatic fiction of any kind both openly and repeatedly; he regarded drama as another "opiate of the masses". Vertov freely admitted one criticism leveled at his efforts on the "Kino-Pravda" series—that the series, while influential, had a limited release.

By the end of the "Kino-Pravda" series, Vertov made liberal use of stop motion

Stop motion

Stop motion is an animation technique to make a physically manipulated object appear to move on its own. The object is moved in small increments between individually photographed frames, creating the illusion of movement when the series of frames is played as a continuous sequence...

, freeze frame

Freeze frame

- Film and Television :*Freeze frame shot, a cinematographic technique*Freeze frame television, a technique making use of freeze frame shots*Freeze Frame, a game on The Price is Right...

s, and other cinematic "artificialities," giving rise to criticisms not just of his trenchant dogmatism, but also of his cinematic technique. Vertov explains himself in "On 'Kinopravda'": in editing "chance film clippings" together for the Kino-Nedelia series, he "began to doubt the necessity of a literary connection between individual visual elements spliced together.... This work served as the point of departure for 'Kinopravda.'" Towards the end of the same essay, Vertov mentions an upcoming project which seems likely to be Man with the Movie Camera, calling it an "experimental film" made without a scenario; just three paragraphs above, Vertov mentions a scene from "Kino Pravda" which should be quite familiar to viewers of Man with the Movie Camera: the peasant works, and so does the urban woman, and so too, the woman film editor selecting the negative...."

Man with a Movie Camera

With Lenin's admission of limited private enterprise through his New Economic PolicyNew Economic Policy

The New Economic Policy was an economic policy proposed by Vladimir Lenin, who called it state capitalism. Allowing some private ventures, the NEP allowed small animal businesses or smoke shops, for instance, to reopen for private profit while the state continued to control banks, foreign trade,...

(NEP), Russia began receiving fiction films from afar, an occurrence that Vertov regarded with undeniable suspicion, calling drama a "corrupting influence" on the proletarian sensibility ("On 'Kinopravda,'" 1924). By this time Vertov had been using his newsreel series as a pedestal to vilify dramatic fiction for several years; he continued his criticisms even after the warm reception of Sergei Eisenstein

Sergei Eisenstein

Sergei Mikhailovich Eisenstein , né Eizenshtein, was a pioneering Soviet Russian film director and film theorist, often considered to be the "Father of Montage"...

's Battleship Potemkin in 1925. Potemkin was a heavily fictionalized film telling the story of a mutiny on a battleship which came about as a result of the sailors' mistreatment; the film was an obvious but skillful propaganda piece glorifying the proletariat. Vertov lost his job at Sovkino

Sovkino

Sovkino was a studio in what now is Ukraine. It was built to compete with Disney over the market of animated movies in the 1930s.Sovkino was also a name of Lenfilm in 1926—1930....

in January 1927, possibly as a result of criticizing a film which effectively preaches the line of the Communist Party

Communist Party of the Soviet Union

The Communist Party of the Soviet Union was the only legal, ruling political party in the Soviet Union and one of the largest communist organizations in the world...

. He was fired for creating "A Sixth Part of the World: Advertising and the Soviet Universe" for the State Trade Organization into a propaganda film, selling the Soviet as an advanced society under the New Economic Policy of Lenin, instead of showing how they fit into the world economy. The Ukraine State Studio hired Vertov to create Man with a Movie Camera.

Vertov says in his essay "The Man with a Movie Camera" that he was fighting "for a decisive cleaning up of film-language, for its complete separation from the language of theater and literature." By the later segments of "Kino-Pravda," Vertov was experimenting heavily, looking to abandon what he considered film clichés (and receiving criticism for it); his experimentation was even more pronounced and dramatic by the time of Man with the Movie Camera (filmed in the Ukraine

Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It has an area of 603,628 km², making it the second largest contiguous country on the European continent, after Russia...

). Some have criticized the obvious stagings in Man With the Movie Camera as being at odds with Vertov's credos "life as it is" and "life caught unawares": the scene of the woman getting out of bed and getting dressed is obviously staged, as is the reversed shot of the chess pieces being pushed off a chess board and the tracking shot which films Mikhail Kaufman riding in a car filming a third car.

However, Vertov's two credos, often used interchangeably, are in fact distinct, as Yuri Tsivian points out in the commentary track on the DVD for Man with the Movie Camera: for Vertov, "life as it is" means to record life as it would be without the camera present. "Life caught unawares" means to record life when surprised, and perhaps provoked, by the presence of a camera (16:04 on the commentary track). This explanation contradicts the common assumption that for Vertov "life caught unawares" meant "life caught unaware of the camera." All of these shots might conform to Vertov's credo "caught unawares." Dziga's slow motion, fast motion, and other camera techniques were a way to dissect the image, Vertov's brother Mikhail described in a interview. It was to be the honest truth of perception. For example, in Man with a Movie Camera, two trains are shown almost melting into each other, although we are taught to see trains as not riding that close, Vertov tried to portray the actual sight of two passing trains. Mikhail talked about Eisenstein's films as different from his and his brother Vertov's in that Eisenstein, "came from the theatre, in the theatre one directs dramas, one strings beads." "We all felt...that through documentary film we could develop a new kind of art. Not only documentary art, or the art of chronicle, but rather an art based on images, the creation of an image-oriented journalism" Mikhail explained. More than even film truth, Man with a Movie Camera, was supposed to be a way to make those in the Soviet Union more efficient in their actions. He slowed down his actions, such as the decision whether to jump or not, you can see the decision in his face, a psychological dissection for the audience. He wanted a peace between the actions of man and the actions of a machine, for them to be, in a sense, one.

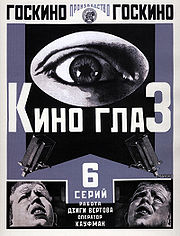

Cine-Eye

Dziga Vertov believed his concept of Kino-Glaz, or "Cine Eye" in English, would help contemporary man evolve from a flawed creature into a higher, more precise form. He compared man unfavorably to machines: “In the face of the machine we are ashamed of man’s inability to control himself, but what are we to do if we find the unerring ways of electricity more exciting than the disorderly haste of active people [...]” "I am an eye. I am a mechanical eye. I, a machine, I am showing you a world, the likes of which only I can see" Dziga was quoted as saying.Like other Russian filmmakers, he attempted to connect his ideas and techniques to the advancement of the aims of the Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

. Whereas Sergei Eisenstein

Sergei Eisenstein

Sergei Mikhailovich Eisenstein , né Eizenshtein, was a pioneering Soviet Russian film director and film theorist, often considered to be the "Father of Montage"...

viewed his montage of attractions as a propaganda tool through which the film-viewing masses could be subjected to “emotional and psychological influence” and therefore able to perceive “the ideological aspect” of the films they were being shown, Vertov believed the Cine-Eye would influence the actual evolution of man, “from a bumbling citizen through the poetry of the machine to the perfect electric man.”

Vertov believed film was too “romantic” and “theatricalised” due to the influence of literature, theater, and music, and that these psychological film-dramas “prevent man from being as precise as a stop watch and hamper his desire for kinship with the machine.”

He desired to move away from “the pre-Revolutionary ‘fictional’ models” of filmmaking to one based on the rhythm of machines, seeking to “bring creative joy to all mechanical labour” and to “bring men closer to machines.”

Late career

Vertov's cinema success continued into the 1930s. In 1931, he released Enthusiasm: Symphony of the Donbass, an examination into Soviet miners. Enthusiasm has been called a 'sound film', with sound recorded on location, and these mechanical sounds woven together, producing a symphony-like effect.Three years later, Three Songs about Lenin looked at the revolution through the eyes of the Russian peasantry. For his film, however, Vertov had been hired by Mezhrabpomfilm

Gorky Film Studio

Gorky Film Studio is a film studio in Moscow, Russian Federation. By the end of the Soviet Union, Gorky Film Studio had produced more than 1,000 films...

, a Soviet studio that produced mainly propaganda efforts. The film, finished in January 1934 for Lenin's obit, was only publicly released in November. A new version of the film was published in 1938, including a longer sequence to reflect Stalin's "achivements" at the end of the film and leaving out footage with "enemies" of that time, including figures like Nikolai Yezhov

Nikolai Yezhov

Nikolai Ivanovich Yezhov or Ezhov was a senior figure in the NKVD under Joseph Stalin during the period of the Great Purge. His reign is sometimes known as the "Yezhovshchina" , "the Yezhov era", a term that began to be used during the de-Stalinization campaign of the 1950s...

, Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev led the Soviet Union during part of the Cold War. He served as First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964, and as Chairman of the Council of Ministers, or Premier, from 1958 to 1964...

, Georgi Dimitrov

Georgi Dimitrov

Georgi Dimitrov Mikhaylov , also known as Georgi Mikhaylovich Dimitrov , was a Bulgarian Communist politician...

and others. Today there exists a 1970 reconstruction by Elizaveta Svilova. With the rise and official sanction of socialist realism

Socialist realism

Socialist realism is a style of realistic art which was developed in the Soviet Union and became a dominant style in other communist countries. Socialist realism is a teleologically-oriented style having its purpose the furtherance of the goals of socialism and communism...

in 1934, Vertov was forced to cut his personal artistic output significantly, eventually becoming little more than an editor for Soviet newsreels. Lullaby, perhaps the last film in which Vertov was able to maintain his artistic vision, was released in 1937. Dziga Vertov died of cancer in 1954, after surviving, unscathed, Stalin's purges.

Vertov's brother Boris Kaufman

Boris Kaufman

Boris Abelevich Kaufman, A.S.C. was a cinematographer. He was the younger brother of famous filmmakers Dziga Vertov and Mikhail Kaufman....

was a noted cinematographer who worked much later for directors such as Elia Kazan

Elia Kazan

Elia Kazan was an American director and actor, described by the New York Times as "one of the most honored and influential directors in Broadway and Hollywood history". Born in Istanbul, the capital of the Ottoman Empire, to Greek parents originally from Kayseri in Anatolia, the family emigrated...

and Sidney Lumet

Sidney Lumet

Sidney Lumet was an American director, producer and screenwriter with over 50 films to his credit. He was nominated for the Academy Award as Best Director for 12 Angry Men , Dog Day Afternoon , Network and The Verdict...

in America; his other brother, Mikhail Kaufman, worked as Vertov's cinematographer until he became a documentarian in his own right. In September 1929 he married his long time collaborator Elizaveta Svilova.

Influence

Vertov's legacy still lives on today. His ideas are echoed in cinéma véritéCinéma vérité

Cinéma vérité is a style of documentary filmmaking, combining naturalistic techniques with stylized cinematic devices of editing and camerawork, staged set-ups, and the use of the camera to provoke subjects. It is also known for taking a provocative stance toward its topics.There are subtle yet...

, the movement of the 1960s named after Vertov's Kino-Pravda. The 1960s and 1970s saw an international revival of interest in Vertov.

The independent, exploratory style of Vertov influenced and inspired many filmmakers and directors like the Situationist Guy Debord

Guy Debord

Guy Ernest Debord was a French Marxist theorist, writer, filmmaker, member of the Letterist International, founder of a Letterist faction, and founding member of the Situationist International . He was also briefly a member of Socialisme ou Barbarie.-Early Life:Guy Debord was born in Paris in 1931...

and independent companies such as "Vertov Industries," in Hawaii. The Dziga Vertov Group

Dziga Vertov Group

The Dziga Vertov Group was formed in 1968 by politically active filmmakers including Jean-Luc Godard and Jean-Pierre Gorin. Their films are defined primarily for Brechtian forms, Marxist ideology, and a lack of personal authorship...

borrowed his name. In 1960, Jean Rouch

Jean Rouch

Jean Rouch was a French filmmaker and anthropologist.He is considered to be one of the founders of the cinéma vérité in France, which shared the aesthetics of the direct cinema spearheaded by Richard Leacock, D.A. Pennebaker and Albert and David Maysles...

used Vertov's filming theory when making Chronicle of a Summer. His partner Edgar Morin

Edgar Morin

Edgar Morin is a French philosopher and sociologist born Edgar Nahoum in Paris on July 8, 1921. He is of Judeo-Spanish origin. He is known for the transdisciplinarity of his works.- Biography :...

coined Cinéma vérité term when describing the style, using direct translation of Vertov’s KinoPravda.

The Free Cinema

Free Cinema

Free Cinema was a documentary film movement that emerged in England in the mid-1950s. The term referred to an absence of propagandised intent or deliberate box office appeal. Co-founded by Lindsay Anderson, though he later disdained the 'movement' tag, with Karel Reisz, Tony Richardson and Lorenza...

movement in the United Kingdom during the 1950s, the Direct Cinema in North America in the late 1950s and early 1960s, and the Candid Eye series in Canada in the 1950s, all essentially owed a debt to Vertov.

This revival of Vertov's legacy included rehabilitation of his reputation in the Soviet Union, with retrospectives of his films, biographical works and writings. In 1962, the first Soviet monograph on Vertov was published, followed by another collection, 'Dziga Vertov: Articles, Diaries, Projects.' To recall the 30th anniversary of Vertov's death, three New York cultural organizations put on the first American retrospective of Vertov's work.

New Media

New media

New media is a broad term in media studies that emerged in the latter part of the 20th century. For example, new media holds out a possibility of on-demand access to content any time, anywhere, on any digital device, as well as interactive user feedback, creative participation and community...

theorist Lev Manovich

Lev Manovich

Lev Manovich is an author of new media books, professor of Visual Arts, University of California, San Diego, U.S. and European Graduate School in Saas-Fee, Switzerland, where he teaches new media art and theory, software studies, and digital humanities...

suggested Vertov as one of the early pioneers of database cinema

Database cinema

One of the principal features defining traditional cinema is a fixed and linear narrative structure. In Database Cinema however, the story develops by selecting scenes from a given collection...

genre in his essay Database as a symbolic form.

Family and personal life

Vertov's brothers Boris KaufmanBoris Kaufman

Boris Abelevich Kaufman, A.S.C. was a cinematographer. He was the younger brother of famous filmmakers Dziga Vertov and Mikhail Kaufman....

and Mikhail Kaufman

Mikhail Kaufman

Mikhail Abramovich Kaufman ; ) was a Russian cinematographer and photographer. He was the younger brother of filmmaker Dziga Vertov and the older brother of cinematographer Boris Kaufman....

were also notable filmmakers, as was his wife, Elizaveta Svilova.

Quotes

- "It is far from simple to show the truth, yet the truth is simple." http://www.nottingham.ac.uk/film/journal/filmrev/man-with-a-movie-camera.htm

- "I am the machine that reveals the world to you as only I alone am able to see it."

- "I was returning from the railroad station. In my ears, there remained chugs and bursts of steam from a departing train. Somebody cries in laughter, a whistle, the station bell, the clanking locomotive...whispers, shouts, farewells. And walking away I thought I need to find a machine not only to describe but to register, to photograph these sounds. Otherwise, one cannot organize or assemble them. They fly like time. Perhaps a camera? That records the visual. But to organize the visual world and not the audible world? Is this the answer?"- Dziga Vertov

- "Our eyes see very little and very badly – so people dreamed up the microscope to let them see invisible phenomena; they invented the telescope...now they have perfected the cinecamera to penetrate more deeply into the visible world, to explore and record visual phenomena so that what is happening now, which will have to be taken account of in the future, is not forgotten."

- "Everybody who cares for his art seeks the essence of his own technique.” (1922)

Filmography

- 1919 Кинонеделя (Kino Nedelya, Cinema Week)

- 1919 Годовщина революции (Anniversary of the Revolution)

- 1922 История гражданской войны (History of the Civil War)

- 1924 Советские игрушки (Soviet Toys)

- 1924 Кино-глаз (Cinema Eye)

- 1925 Киноправда (Kino-PravdaKino-PravdaKino-Pravda was a newsreel series by Dziga Vertov, Elizaveta Svilova, and Mikhail Kaufman.Working mainly during the 1920s, Vertov promoted the concept of kino-pravda, or film-truth, through his newsreel series. His driving vision was to capture fragments of actuality which, when organized...

) - 1926 Шестая часть мира (A Sixth of the World/The Sixth Part of the World)

- 1928 Одиннадцатый (The Eleventh Year)

- 1929 Человек с киноаппаратом (Man with a Movie CameraMan with a Movie CameraMan with a Movie Camera , sometimes called The Man with the Movie Camera, The Man with a Camera, The Man With the Kinocamera, or Living Russia is an experimental 1929 silent documentary film, with no story and no actors, by Russian director Dziga Vertov, edited by his wife Elizaveta...

) - 1930 Энтузиазм (Симфония Донбаса) (Enthusiasm)

- 1934 Три песни о Ленине (Three Songs About LeninThree Songs About LeninThree Songs About Lenin is a documentary silent film by Russian filmmaker Dziga Vertov. It is based on three admiring songs sung by anonymous people in Soviet Russia about Vladimir Ilyich Lenin. It is made up of 3 episodes and is 57 minutes long....

) - 1937 Памяти Серго Орджоникидзе (In Memory of Sergo Ordzhonikidze)

- 1937 Колыбельная (Lullaby)

- 1938 Три героини (Three Heroines)

- 1942 Казахстан — фронту! (Kazakhstan for the Front!)

- 1944 В горах Ала-Тау (In the Mountains of Ala-Tau)

- 1954 Новости дня (News of the Day)

See also

- Political CinemaPolitical cinemaPolitical cinema in the narrow sense of the term is a cinema which portrays current or historical events or social conditions in a partisan way in order to inform or to agitate the spectator...

- Databases

- New Media ArtNew media artNew media art is a genre that encompasses artworks created with new media technologies, including digital art, computer graphics, computer animation, virtual art, Internet art, interactive art, computer robotics, and art as biotechnology...

- Cinéma véritéCinéma véritéCinéma vérité is a style of documentary filmmaking, combining naturalistic techniques with stylized cinematic devices of editing and camerawork, staged set-ups, and the use of the camera to provoke subjects. It is also known for taking a provocative stance toward its topics.There are subtle yet...

- Pure cinemaPure cinemaPure Cinema is the film theory and practice whereby movie makers create a more emotionally intense experience using autonomous film techniques, as opposed to using stories, characters, or actors....

- MontageMontage-Filmmaking:*Montage , a technique which uses rapid editing, special effects and music to present compressed narrative information*Soviet montage theory in the 1920s-Other:* Montage , Documentary television series from 1960s and 1970s...

- Abstract filmAbstract filmAbstract film is a subgenre of experimental film. Its history often overlaps with the concerns and history of visual music. Some of the earliest abstract motion pictures known to survive are those produced by a group of German artists working in the early 1920s, a movement referred to as Absolute...