Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin

Encyclopedia

Dorothy Mary Hodgkin OM

, FRS (12 May 1910 – 29 July 1994), née Crowfoot, was a British chemist

, credited with the development of protein crystallography.

She advanced the technique of X-ray crystallography

, a method used to determine the three dimensional structures of biomolecules. Among her most influential discoveries are the confirmation of the structure of penicillin

that Ernst Boris Chain

had previously surmised, and then the structure of vitamin B12

, for which she was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry

.

In 1969, after 35 years of work and five years after winning the Nobel Prize, Hodgkin was able to decipher the structure of insulin

. X-ray crystallography became a widely used tool and was critical in later determining the structures of many biological molecules such as DNA

where knowledge of structure is critical to an understanding of function. She is regarded as one of the pioneer scientists in the field of X-ray crystallography studies of biomolecule

s.

, Egypt, to John Winter Crowfoot (1873 – 1959), excavator and scholar of classics, and Grace Mary Hood (1877 – 1957). For the first four years of her life she lived as an English expatriate in Asia Minor

, returning to England only a few months each year. She spent the period of World War I

in the UK under the care of relatives and friends, but separated from her parents. After the war, her mother decided to stay home in England and educate her children, a period that Hodgkin later described as the happiest in her life.

In 1921, she entered the Sir John Leman Grammar School

in Beccles, England. She travelled abroad frequently to visit her parents in Cairo and Khartoum

. Both her father and her mother had a strong influence with their Puritan

ethic of selflessness and service to humanity which reverberated in her later achievements.

at Somerville College, Oxford

, then one of the University of Oxford

colleges for women only.

She also studied at the University of Cambridge

under the tutelage of John Desmond Bernal, where she became aware of the potential of X-ray crystallography to determine the structure of protein

s.

In 1934, she moved back to Oxford and two years later, in 1936, she became a research fellow at Somerville College, a post which she held until 1977. In the 1940s, one of her students was future Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher

, who installed a portrait of Hodgkin in Downing Street in the 1980s.

Together with Sydney Brenner

, Jack Dunitz, Leslie Orgel

, and Beryl M. Oughton, she was one of the first people in April 1953 to see the model of the structure of DNA, constructed by Francis Crick

and James Watson

; at the time she and the other scientists were working at Cambridge University's Cavendish Laboratory.

In 1960 she was appointed Wolfson Research Professor at the Royal Society

.

was one of her most extraordinary research projects. It began in 1934 when she was offered a small sample of crystalline insulin by Robert Robinson. The hormone

captured her imagination because of the intricate and wide-ranging effect it has in the body. However, at this stage X-ray crystallography had not been developed far enough to cope with the complexity of the insulin molecule. She and others spent many years improving the technique. Larger and more complex molecules were being tackled (see timeline below) until in 1969 – 35 years later – the structure of insulin was finally resolved. But her quest was not finished then. She cooperated with other laboratories active in insulin research, gave advice, and travelled the world giving talks about insulin and its importance for diabetes.

John Desmond Bernal greatly influenced her life both scientifically and politically. He was a distinguished scientist of great repute in the scientific world, a member of the Communist party

, and a faithful supporter of successive Soviet regimes until their invasion of Hungary

. She always referred to him as "Sage"; intermittently, they were lovers. The conventional marriages of both Bernal and Hodgkin were far from smooth.

In 1937, Dorothy married Thomas Lionel Hodgkin

, then recently returned from working for the Colonial Office

and moving into adult education. He later became a well-known Oxford Lecturer, author of several fundamental Africanist books and a one-time member of the Communist party

. She always consulted him concerning important problems and decisions. In 1961 Thomas became an advisor to Kwame Nkrumah

, President of Ghana

, where he remained for extended periods, and where she often visited him. The couple had three children. Because of her political activity and her husband's association with the Communist Party, she was not allowed to enter the US except by CIA waiver.

The couple had three children Luke (born 1938), Elizabeth (born 1941) and Toby (born 1946).

and stopping conflict. As a consequence she was President of Pugwash

from 1976 to 1988.

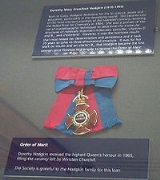

Apart from the Nobel Prize in chemistry in 1964, she was a recipient of the Order of Merit

Apart from the Nobel Prize in chemistry in 1964, she was a recipient of the Order of Merit

, a recipient of the Copley Medal

, a Fellow of the Royal Society

, The Lenin Peace Prize

, and was Chancellor

of Bristol University

from 1970 to 1988.

Council offices in the London Borough of Hackney

and buildings at Bristol University

and Keele University

are named after her.

The Royal Society has established the prestigious Dorothy Hodgkin fellowship for early career stage researchers.

(ballerina/choreographer), Elisabeth Frink

(sculptor) & Daphne du Maurier

(writer). All except Hodgkin were Dames Commander of the Order of the British Empire (DBEs).

In 2010, during its 350th anniversary, the Royal Society celebrated with the publication of 10 stamps of some of its most illustrious members, bestowing Professor Hodgkin with her second stamp. She was in the company of nine men: Benjamin Franklin

, Edward Jenner

, Joseph Lister

, Isaac Newton

, Robert Boyle

, Ernest Rutherford

, Nicholas Shackleton

, Charles Babbage

, Alfred Russel Wallace

.

Order of Merit

The Order of Merit is a British dynastic order recognising distinguished service in the armed forces, science, art, literature, or for the promotion of culture...

, FRS (12 May 1910 – 29 July 1994), née Crowfoot, was a British chemist

Chemist

A chemist is a scientist trained in the study of chemistry. Chemists study the composition of matter and its properties such as density and acidity. Chemists carefully describe the properties they study in terms of quantities, with detail on the level of molecules and their component atoms...

, credited with the development of protein crystallography.

She advanced the technique of X-ray crystallography

X-ray crystallography

X-ray crystallography is a method of determining the arrangement of atoms within a crystal, in which a beam of X-rays strikes a crystal and causes the beam of light to spread into many specific directions. From the angles and intensities of these diffracted beams, a crystallographer can produce a...

, a method used to determine the three dimensional structures of biomolecules. Among her most influential discoveries are the confirmation of the structure of penicillin

Penicillin

Penicillin is a group of antibiotics derived from Penicillium fungi. They include penicillin G, procaine penicillin, benzathine penicillin, and penicillin V....

that Ernst Boris Chain

Ernst Boris Chain

Sir Ernst Boris Chain was a German-born British biochemist, and a 1945 co-recipient of the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine for his work on penicillin.-Biography:...

had previously surmised, and then the structure of vitamin B12

Vitamin B12

Vitamin B12, vitamin B12 or vitamin B-12, also called cobalamin, is a water-soluble vitamin with a key role in the normal functioning of the brain and nervous system, and for the formation of blood. It is one of the eight B vitamins...

, for which she was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry

Nobel Prize in Chemistry

The Nobel Prize in Chemistry is awarded annually by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences to scientists in the various fields of chemistry. It is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Alfred Nobel in 1895, awarded for outstanding contributions in chemistry, physics, literature,...

.

In 1969, after 35 years of work and five years after winning the Nobel Prize, Hodgkin was able to decipher the structure of insulin

Insulin

Insulin is a hormone central to regulating carbohydrate and fat metabolism in the body. Insulin causes cells in the liver, muscle, and fat tissue to take up glucose from the blood, storing it as glycogen in the liver and muscle....

. X-ray crystallography became a widely used tool and was critical in later determining the structures of many biological molecules such as DNA

DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid is a nucleic acid that contains the genetic instructions used in the development and functioning of all known living organisms . The DNA segments that carry this genetic information are called genes, but other DNA sequences have structural purposes, or are involved in...

where knowledge of structure is critical to an understanding of function. She is regarded as one of the pioneer scientists in the field of X-ray crystallography studies of biomolecule

Biomolecule

A biomolecule is any molecule that is produced by a living organism, including large polymeric molecules such as proteins, polysaccharides, lipids, and nucleic acids as well as small molecules such as primary metabolites, secondary metabolites, and natural products...

s.

Early years

Dorothy Mary Crowfoot was born on 12 May 1910 in CairoCairo

Cairo , is the capital of Egypt and the largest city in the Arab world and Africa, and the 16th largest metropolitan area in the world. Nicknamed "The City of a Thousand Minarets" for its preponderance of Islamic architecture, Cairo has long been a centre of the region's political and cultural life...

, Egypt, to John Winter Crowfoot (1873 – 1959), excavator and scholar of classics, and Grace Mary Hood (1877 – 1957). For the first four years of her life she lived as an English expatriate in Asia Minor

Asia Minor

Asia Minor is a geographical location at the westernmost protrusion of Asia, also called Anatolia, and corresponds to the western two thirds of the Asian part of Turkey...

, returning to England only a few months each year. She spent the period of World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

in the UK under the care of relatives and friends, but separated from her parents. After the war, her mother decided to stay home in England and educate her children, a period that Hodgkin later described as the happiest in her life.

In 1921, she entered the Sir John Leman Grammar School

Sir John Leman High School

Sir John Leman High School is currently a mixed-sex, 13-18 comprehensive school serving part of the Waveney region in north Suffolk, England. The school is located on the western edge of the town of Beccles and serves the surrounding area, including Worlingham and parts of Lowestoft...

in Beccles, England. She travelled abroad frequently to visit her parents in Cairo and Khartoum

Khartoum

Khartoum is the capital and largest city of Sudan and of Khartoum State. It is located at the confluence of the White Nile flowing north from Lake Victoria, and the Blue Nile flowing west from Ethiopia. The location where the two Niles meet is known as "al-Mogran"...

. Both her father and her mother had a strong influence with their Puritan

Puritan

The Puritans were a significant grouping of English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries. Puritanism in this sense was founded by some Marian exiles from the clergy shortly after the accession of Elizabeth I of England in 1558, as an activist movement within the Church of England...

ethic of selflessness and service to humanity which reverberated in her later achievements.

Education and research

She developed a passion for chemistry from a young age, and her mother fostered her interest in science in general. Her excellent early education prepared her well for university. At age 18 she started studying chemistryChemistry

Chemistry is the science of matter, especially its chemical reactions, but also its composition, structure and properties. Chemistry is concerned with atoms and their interactions with other atoms, and particularly with the properties of chemical bonds....

at Somerville College, Oxford

Somerville College, Oxford

Somerville College is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in England, and was one of the first women's colleges to be founded there...

, then one of the University of Oxford

University of Oxford

The University of Oxford is a university located in Oxford, United Kingdom. It is the second-oldest surviving university in the world and the oldest in the English-speaking world. Although its exact date of foundation is unclear, there is evidence of teaching as far back as 1096...

colleges for women only.

She also studied at the University of Cambridge

University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a public research university located in Cambridge, United Kingdom. It is the second-oldest university in both the United Kingdom and the English-speaking world , and the seventh-oldest globally...

under the tutelage of John Desmond Bernal, where she became aware of the potential of X-ray crystallography to determine the structure of protein

Protein

Proteins are biochemical compounds consisting of one or more polypeptides typically folded into a globular or fibrous form, facilitating a biological function. A polypeptide is a single linear polymer chain of amino acids bonded together by peptide bonds between the carboxyl and amino groups of...

s.

In 1934, she moved back to Oxford and two years later, in 1936, she became a research fellow at Somerville College, a post which she held until 1977. In the 1940s, one of her students was future Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher, was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990...

, who installed a portrait of Hodgkin in Downing Street in the 1980s.

Together with Sydney Brenner

Sydney Brenner

Sydney Brenner, CH FRS is a South African biologist and a 2002 Nobel prize in Physiology or Medicine laureate, shared with H...

, Jack Dunitz, Leslie Orgel

Leslie Orgel

Leslie Eleazer Orgel FRS was a British chemist.Born in London, England, Orgel received his B.A. in chemistry with first class honours from Oxford University in 1949...

, and Beryl M. Oughton, she was one of the first people in April 1953 to see the model of the structure of DNA, constructed by Francis Crick

Francis Crick

Francis Harry Compton Crick OM FRS was an English molecular biologist, biophysicist, and neuroscientist, and most noted for being one of two co-discoverers of the structure of the DNA molecule in 1953, together with James D. Watson...

and James Watson

James D. Watson

James Dewey Watson is an American molecular biologist, geneticist, and zoologist, best known as one of the co-discoverers of the structure of DNA in 1953 with Francis Crick...

; at the time she and the other scientists were working at Cambridge University's Cavendish Laboratory.

In 1960 she was appointed Wolfson Research Professor at the Royal Society

Royal Society

The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, known simply as the Royal Society, is a learned society for science, and is possibly the oldest such society in existence. Founded in November 1660, it was granted a Royal Charter by King Charles II as the "Royal Society of London"...

.

Insulin structure

InsulinInsulin

Insulin is a hormone central to regulating carbohydrate and fat metabolism in the body. Insulin causes cells in the liver, muscle, and fat tissue to take up glucose from the blood, storing it as glycogen in the liver and muscle....

was one of her most extraordinary research projects. It began in 1934 when she was offered a small sample of crystalline insulin by Robert Robinson. The hormone

Hormone

A hormone is a chemical released by a cell or a gland in one part of the body that sends out messages that affect cells in other parts of the organism. Only a small amount of hormone is required to alter cell metabolism. In essence, it is a chemical messenger that transports a signal from one...

captured her imagination because of the intricate and wide-ranging effect it has in the body. However, at this stage X-ray crystallography had not been developed far enough to cope with the complexity of the insulin molecule. She and others spent many years improving the technique. Larger and more complex molecules were being tackled (see timeline below) until in 1969 – 35 years later – the structure of insulin was finally resolved. But her quest was not finished then. She cooperated with other laboratories active in insulin research, gave advice, and travelled the world giving talks about insulin and its importance for diabetes.

Private life

Hodgkin's scientific mentor ProfessorProfessor

A professor is a scholarly teacher; the precise meaning of the term varies by country. Literally, professor derives from Latin as a "person who professes" being usually an expert in arts or sciences; a teacher of high rank...

John Desmond Bernal greatly influenced her life both scientifically and politically. He was a distinguished scientist of great repute in the scientific world, a member of the Communist party

Communist Party of Great Britain

The Communist Party of Great Britain was the largest communist party in Great Britain, although it never became a mass party like those in France and Italy. It existed from 1920 to 1991.-Formation:...

, and a faithful supporter of successive Soviet regimes until their invasion of Hungary

1956 Hungarian Revolution

The Hungarian Revolution or Uprising of 1956 was a spontaneous nationwide revolt against the government of the People's Republic of Hungary and its Soviet-imposed policies, lasting from 23 October until 10 November 1956....

. She always referred to him as "Sage"; intermittently, they were lovers. The conventional marriages of both Bernal and Hodgkin were far from smooth.

In 1937, Dorothy married Thomas Lionel Hodgkin

Thomas Lionel Hodgkin

Thomas Lionel Hodgkin was an English Marxist historian of Africa "who did more than anyone to establish the serious study of African history" in the UK. His wife was the scientist Dorothy Hodgkin.-Life:Thomas Lionel Hodgkin was born into an academic family...

, then recently returned from working for the Colonial Office

Colonial Office

Colonial Office is the government agency which serves to oversee and supervise their colony* Colonial Office - The British Government department* Office of Insular Affairs - the American government agency* Reichskolonialamt - the German Colonial Office...

and moving into adult education. He later became a well-known Oxford Lecturer, author of several fundamental Africanist books and a one-time member of the Communist party

Communist Party of Great Britain

The Communist Party of Great Britain was the largest communist party in Great Britain, although it never became a mass party like those in France and Italy. It existed from 1920 to 1991.-Formation:...

. She always consulted him concerning important problems and decisions. In 1961 Thomas became an advisor to Kwame Nkrumah

Kwame Nkrumah

Kwame Nkrumah was the leader of Ghana and its predecessor state, the Gold Coast, from 1952 to 1966. Overseeing the nation's independence from British colonial rule in 1957, Nkrumah was the first President of Ghana and the first Prime Minister of Ghana...

, President of Ghana

President of Ghana

The President of Ghana is the elected head of state and head of government of Ghana. Officially styled President of the Republic of Ghana and Commander-in-Chief of the Ghanaian Armed Forces. The current President of Ghana is Prof. John Atta Mills, who took office in January...

, where he remained for extended periods, and where she often visited him. The couple had three children. Because of her political activity and her husband's association with the Communist Party, she was not allowed to enter the US except by CIA waiver.

The couple had three children Luke (born 1938), Elizabeth (born 1941) and Toby (born 1946).

Social activities

Despite her scientific specialisation and excellence she was by no means a single-minded and one-sided scientist. She received many honours but was more interested in exchange with other scientists. She often employed her intelligence to think about other people's problems and was concerned about social inequalitiesSocial inequality

Social inequality refers to a situation in which individual groups in a society do not have equal social status. Areas of potential social inequality include voting rights, freedom of speech and assembly, the extent of property rights and access to education, health care, quality housing and other...

and stopping conflict. As a consequence she was President of Pugwash

Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs

The Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs is an international organization that brings together scholars and public figures to work toward reducing the danger of armed conflict and to seek solutions to global security threats...

from 1976 to 1988.

Honours

Order of Merit

The Order of Merit is a British dynastic order recognising distinguished service in the armed forces, science, art, literature, or for the promotion of culture...

, a recipient of the Copley Medal

Copley Medal

The Copley Medal is an award given by the Royal Society of London for "outstanding achievements in research in any branch of science, and alternates between the physical sciences and the biological sciences"...

, a Fellow of the Royal Society

Royal Society

The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, known simply as the Royal Society, is a learned society for science, and is possibly the oldest such society in existence. Founded in November 1660, it was granted a Royal Charter by King Charles II as the "Royal Society of London"...

, The Lenin Peace Prize

Lenin Peace Prize

The International Lenin Peace Prize was the Soviet Union's equivalent to the Nobel Peace Prize, named in honor of Vladimir Lenin. It was awarded by a panel appointed by the Soviet government, to notable individuals whom the panel indicated had "strengthened peace among peoples"...

, and was Chancellor

Chancellor (education)

A chancellor or vice-chancellor is the chief executive of a university. Other titles are sometimes used, such as president or rector....

of Bristol University

University of Bristol

The University of Bristol is a public research university located in Bristol, United Kingdom. One of the so-called "red brick" universities, it received its Royal Charter in 1909, although its predecessor institution, University College, Bristol, had been in existence since 1876.The University is...

from 1970 to 1988.

Council offices in the London Borough of Hackney

London Borough of Hackney

The London Borough of Hackney is a London borough of North/North East London, and forms part of inner London. The local authority is Hackney London Borough Council....

and buildings at Bristol University

University of Bristol

The University of Bristol is a public research university located in Bristol, United Kingdom. One of the so-called "red brick" universities, it received its Royal Charter in 1909, although its predecessor institution, University College, Bristol, had been in existence since 1876.The University is...

and Keele University

Keele University

Keele University is a campus university near Newcastle-under-Lyme in Staffordshire, England. Founded in 1949 as an experimental college dedicated to a broad curriculum and interdisciplinary study, Keele is most notable for pioneering the dual honours degree in Britain...

are named after her.

The Royal Society has established the prestigious Dorothy Hodgkin fellowship for early career stage researchers.

Cultural references

Dorothy Hodgkin was one of five 'Women of Achievement' selected for a set of British stamps issued in August 1996. The others were Marea Hartman (sports administrator), Margot FonteynMargot Fonteyn

Dame Margot Fonteyn de Arias, DBE , was an English ballerina of the 20th century. She is widely regarded as one of the greatest classical ballet dancers of all time...

(ballerina/choreographer), Elisabeth Frink

Elisabeth Frink

Dame Elisabeth Jean Frink, DBE, CH, RA was an English sculptor and printmaker...

(sculptor) & Daphne du Maurier

Daphne du Maurier

Dame Daphne du Maurier, Lady Browning DBE was a British author and playwright.Many of her works have been adapted into films, including the novels Rebecca and Jamaica Inn and the short stories "The Birds" and "Don't Look Now". The first three were directed by Alfred Hitchcock.Her elder sister was...

(writer). All except Hodgkin were Dames Commander of the Order of the British Empire (DBEs).

In 2010, during its 350th anniversary, the Royal Society celebrated with the publication of 10 stamps of some of its most illustrious members, bestowing Professor Hodgkin with her second stamp. She was in the company of nine men: Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin

Dr. Benjamin Franklin was one of the Founding Fathers of the United States. A noted polymath, Franklin was a leading author, printer, political theorist, politician, postmaster, scientist, musician, inventor, satirist, civic activist, statesman, and diplomat...

, Edward Jenner

Edward Jenner

Edward Anthony Jenner was an English scientist who studied his natural surroundings in Berkeley, Gloucestershire...

, Joseph Lister

Joseph Lister, 1st Baron Lister

Joseph Lister, 1st Baron Lister OM, FRS, PC , known as Sir Joseph Lister, Bt., between 1883 and 1897, was a British surgeon and a pioneer of antiseptic surgery, who promoted the idea of sterile surgery while working at the Glasgow Royal Infirmary...

, Isaac Newton

Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton PRS was an English physicist, mathematician, astronomer, natural philosopher, alchemist, and theologian, who has been "considered by many to be the greatest and most influential scientist who ever lived."...

, Robert Boyle

Robert Boyle

Robert Boyle FRS was a 17th century natural philosopher, chemist, physicist, and inventor, also noted for his writings in theology. He has been variously described as English, Irish, or Anglo-Irish, his father having come to Ireland from England during the time of the English plantations of...

, Ernest Rutherford

Ernest Rutherford

Ernest Rutherford, 1st Baron Rutherford of Nelson OM, FRS was a New Zealand-born British chemist and physicist who became known as the father of nuclear physics...

, Nicholas Shackleton

Nicholas Shackleton

Sir Nicholas John Shackleton FRS was a British geologist and climatologist who specialised in the Quaternary Period...

, Charles Babbage

Charles Babbage

Charles Babbage, FRS was an English mathematician, philosopher, inventor and mechanical engineer who originated the concept of a programmable computer...

, Alfred Russel Wallace

Alfred Russel Wallace

Alfred Russel Wallace, OM, FRS was a British naturalist, explorer, geographer, anthropologist and biologist...

.

Dorothy Hodgkin Memorial Lecture

An annual memorial lecture is held every March in honour of Hodgkins work, past speakers have included- Professor Louise JohnsonLouise JohnsonDame Professor Louise Napier Johnson, DBE, FRS, is a retired British biochemist. She was David Phillips Professor of Molecular Biophysics at the University of Oxford from 1990 to 2007, and is now an emeritus professor....

, "Dorothy Hodgkin and penicillin", 4/3/99. - Professor Judith HowardJudith HowardJudith Ann Kathleen Howard, CBE, FRS, is a distinguished British chemist, crystallographer and Professor at Durham University....

, "The Interface of Chemistry and Biology Increasingly in Focus", *13/03/00. - Professor Jenny Glusker, "Vitamin B12 and Dorothy: Their impact on structural science", 15/05/01.

- Professor Pauline Harrison CBE, From Crystallography to Metals, Metabolism and Medicine, 05/03/02.

- Dr Claire Naylor, Pathogenic Proteins : how bacterial agents cause disease, 04/03/03.

- Dr Margaret Adams, "A Piece in the Jigsaw: G6PD – The protein behind an hereditary disease", 09/03/04.

- Dr. Margaret Rayman, "Selenium in cancer prevention", 10/03/05.

- Dr Elena Conti, "Making sense of nonsense: structural studies of RNA degradation and disease", 09/03/06.

- Professor Jenny Martin, "The name's Bond – Disulphide Bond", 06/03/07.

- Professor E. Yvonne Jones, "Postcards from the surface: The Structural Biology of Cell-Cell Communication, 04/03/08.

- Professor Pamela J. BjorkmanPamela J. BjorkmanPamela J. Bjorkman is an American biochemist. She is the Max Delbrück Professor of Biology at the California Institute of Technology , Adjunct Professor of biochemistry at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, and an investigator for the Howard Hughes Medical Institute...

, "Your mother's antibodies: How you get them and how we might improve them to combat HIV", 11/03/09. - Professor Elspeth Garman, "Crystallography 100 years A.D (After Dorothy)" 09/03/2010.

- Professor Eleanor DodsonEleanor DodsonEleanor Joy Dodson FRS is a distinguished biologist who specialises in computational modelling of protein crystallography. She holds a chair in the Department of Chemistry at the University of York...

"Mathematics in the service of Crystallography" 10/03/2011.

Timeline of her discoveries

Hodgkin determined the three-dimensional structures of the following biomolecules:- CholesterolCholesterolCholesterol is a complex isoprenoid. Specifically, it is a waxy steroid of fat that is produced in the liver or intestines. It is used to produce hormones and cell membranes and is transported in the blood plasma of all mammals. It is an essential structural component of mammalian cell membranes...

in 1937 - PenicillinPenicillinPenicillin is a group of antibiotics derived from Penicillium fungi. They include penicillin G, procaine penicillin, benzathine penicillin, and penicillin V....

in 1945 - Vitamin B12Vitamin B12Vitamin B12, vitamin B12 or vitamin B-12, also called cobalamin, is a water-soluble vitamin with a key role in the normal functioning of the brain and nervous system, and for the formation of blood. It is one of the eight B vitamins...

in 1954 - InsulinInsulinInsulin is a hormone central to regulating carbohydrate and fat metabolism in the body. Insulin causes cells in the liver, muscle, and fat tissue to take up glucose from the blood, storing it as glycogen in the liver and muscle....

in 1969

See also

- Ferry, Georgina. 1998. Dorothy Hodgkin A Life. Granta Books, London.

- Dodson, Guy, Jenny P. Glusker, and David Sayre (eds.). 1981. Structural Studies on Molecules of Biological Interest: A Volume in Honour of Professor Dorothy Hodgkin. Oxford: The Clarendon Press.

- Glusker, Jenny P. in Out of the Shadows – Contributions of 20th Century Women to Physics.

- Wolfers, Michael, Thomas Hodgkin. Wandering scholar. A biography., Merlin Press, 2007

- Royal Society of Edinburgh obituary

External links

- Dorothy Hodgkin tells her life story at Web of Stories (video)

- CWP – Dorothy Hodgkin in a study of contributions of women to physics

- Review of Ferry's biography on the Pugwash website

- Encyclopaedia Britannica, Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin

- Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin: A Founder of Protein Crystallography

- Nobel Prize 1964 page