.gif)

Czechoslovak Republic (1918–1938)

Encyclopedia

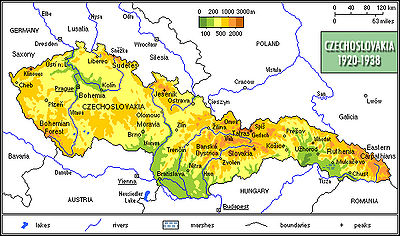

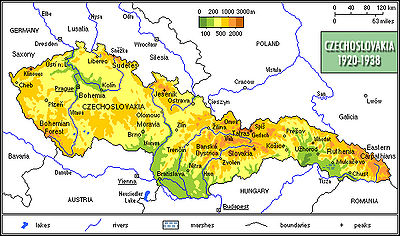

The First Czechoslovak Republic (Czech první Československá republika, Slovak prvá Československá republika or colloquially Prvá republika ), refers to the first Czechoslovak state that existed from 1918 to 1938. The state was commonly called Czechoslovakia (Československo). It was composed of Bohemia

, Moravia

, Czech Silesia

, Slovakia

and Subcarpathian Ruthenia. After 1933 Czechoslovakia remained the only functioning democracy in central and eastern Europe as the other states had authoritarian or autocratic regimes leading them. Under enormous pressure from Nazi Germany

and the Sudeten German minority living in the country, Czechoslovakia was forced to cede the German-populated Sudetenland

region to Germany on October 1, 1938, as agreed in the Munich Agreement

as well as southern parts of Slovakia

and Subcarpathian Ruthenia to Hungary

and the Zaolzie

region in Silesia

to Poland

. This effectively ended the First Czechoslovak Republic, which was succeeded by the Second Czechoslovak Republic

.

was proclaimed on October 28, 1918, by the Czechoslovak National Council in Prague

. Several ethnic groups and territories with different historical, political, and economic traditions had to be blended into a new state structure. The origin of the First Republic lies in Point 10 of Woodrow Wilson's Fourteen Points: "The peoples of Austria-Hungary, whose place among the nations we wish to see safeguarded and assured, should be accorded the freest opportunity to autonomous development."

The full boundaries of the country and the organization of its government was finally established in the Czechoslovak Constitution of 1920

. Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk

had been recognized by WWI Allies

as the leader of the Provisional Czechoslovak Government, and in 1920 he was elected the country's first president. He was re-elected in 1925 and 1929, serving as President until December 14, 1935 when he resigned due to poor health. He was succeeded by Edvard Beneš

.

Following the Anschluss

of Nazi Germany

and Austria

in March 1938, Nazi leader Adolf Hitler

's next target for annexation was Czechoslovakia

. His pretext was the privations suffered by ethnic German

populations living in Czechoslovakia's northern and western border regions, known collectively as the Sudetenland

. Their incorporation into Nazi Germany would leave the rest of Czechoslovakia powerless to resist subsequent occupation.

. As the principal founding father of the republic, Masaryk was regarded similar to the way George Washington

is regarded in the United States

. Such universal respect enabled Masaryk to overcome seemingly irresolvable political problems. Even to this day, Masaryk is regarded as the symbol of Czechoslovak democracy.

The Constitution of 1920 approved the provisional constitution of 1918 in its basic features. The Czechoslovak state was conceived as a parliamentary democracy, guided primarily by the National Assembly

, consisting of the Senate

and the Chamber of Deputies

, whose members were to be elected on the basis of universal suffrage

. The National Assembly was responsible for legislative initiative and was given supervisory control over the executive

and judiciary

as well. Every seven years it elected the president and confirmed the cabinet appointed by him. Executive power was to be shared by the president and the cabinet; the latter, responsible to the National Assembly, was to prevail. The reality differed somewhat from this ideal, however, during the strong presidencies of Masaryk and his successor, Beneš. The constitution of 1920 provided for the central government to have a high degree of control over local government. From 1928 and 1940, Czechoslovakia was divided into the four "lands" (Czech

: "země", Slovak

: "krajiny"); Bohemia, Moravia-Silesia, Slovakia and Carpathian Ruthenia. Although in 1927 assemblies were provided for Bohemia, Slovakia, and Ruthenia, their jurisdiction was limited to adjusting laws and regulations of the central government to local needs. The central government appointed one third of the members of these assemblies. The constitution identified the "Czechoslovak nation" as the creator and principal constituent of the Czechoslovak state and established Czech and Slovak as official languages. The concept of the Czechoslovak nation was necessary in order to justify the establishment of Czechoslovakia towards the world, because otherwise the statistical majority of the Czechs as compared to Germans would have been rather weak, and there would have been more Germans in the state than Slovaks

. National minorities were assured special protection; in districts where they constituted 20% of the population, members of minority groups were granted full freedom to use their language in everyday life, in schools, and in matters dealing with authorities.

The operation of the new Czechoslovak government was distinguished by stability. Largely responsible for this were the well-organized political parties

The operation of the new Czechoslovak government was distinguished by stability. Largely responsible for this were the well-organized political parties

that emerged as the real centers of power. Excluding the period from March 1926 to November 1929, when the coalition did not hold, a coalition of five Czechoslovak parties constituted the backbone of the government: Republican Party of Agricultural and Smallholder People, Czechoslovak Social Democratic Party, Czechoslovak National Socialist Party, Czechoslovak People's Party, and Czechoslovak National Democratic Party. The leaders of these parties became known as the "Pětka

" (pron. pyetka) (The Five). The Pětka was headed by Antonin Svehla

, who held the office of prime minister for most of the 1920s and designed a pattern of coalition politics that survived until 1938. The coalition's policy was expressed in the slogan "We have agreed that we will agree." German

parties also participated in the government in the beginning of 1926. Hungarian

s parties, influenced by irredentist propaganda from Hungary, never joined the Czechoslovak government but were not openly hostile:

Edvard Beneš

Edvard Beneš

, Czechoslovak foreign minister

from 1918 to 1935, created the system of alliances that determined the republic's international stance until 1938. A democratic statesman of Western orientation, Beneš relied heavily on the League of Nations

as guarantor of the post war status quo

and the security of newly formed states. He negotiated the Little Entente

(an alliance with Yugoslavia

and Romania

) in 1921 to counter Hungarian

revanchism

and Habsburg

restoration. He attempted further to negotiate treaties with Britain

and France

, seeking their promises of assistance in the event of aggression against the small, democratic Czechoslovak Republic

. Britain remained intransigent in its isolationist policy, and in 1924 Beneš concluded a separate alliance with France. Beneš's Western policy received a serious blow as early as 1925. The Locarno Pact, which paved the way for Germany

's admission to the League of Nations

, guaranteed Germany

's western border. French troops were thus left immobilized on the Rhine, making French assistance to Czechoslovakia difficult. In addition, the treaty stipulated that Germany's eastern frontier would remain subject to negotiation. When Adolf Hitler

came to power in 1933, fear of German aggression became widespread in eastern Central Europe. Beneš ignored the possibility of a stronger Central European alliance system, remaining faithful to his Western policy. He did, however, seek the participation of the Soviet Union

in an alliance to include France

. (Beneš's earlier attitude towards the Soviet regime had been one of caution.) In 1935 the Soviet Union signed treaties with France and Czechoslovakia. In essence, the treaties provided that the Soviet Union would come to Czechoslovakia's aid only if French assistance came first.

In 1935, when Beneš succeeded Masaryk as president, and Prime Minister Milan Hodža took over the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Hodža's efforts to strengthen alliances in Central Europe came too late. In February 1936 the foreign ministry came under the direction of Kamil Krofta

, an adherent of Beneš's line.

and glass industries and the sugar refineries; more than 40% of all its distilleries and breweries; the Škoda Works

of Pilsen (Plzeň), which produced armaments, locomotives, automobiles, and machinery; and the chemical industry of northern Bohemia

. Seventeen percent of all Hungarian

industry that had developed in Slovakia during the late 19th century also fell to the republic. Czechoslovakia was one of the world's 10 most industrialized states.

The Czech lands were far more industrialized than Slovakia. In Bohemia

, Moravia

, and Silesia

, 39% of the population was employed in industry and 31% in agriculture and forestry

. Most light and heavy industry was located in the Sudetenland

and was owned by Germans and controlled by German-owned banks. Czechs

controlled only 20 to 30% of all industry. In Slovakia 17.1% of the population was employed in industry, and 60.4% worked in agriculture and forestry. Only 5% of all industry in Slovakia was in Slovak

hands. Carpathian Ruthenia

was essentially without industry.

In the agricultural sector, a program of reform introduced soon after the establishment of the republic was intended to rectify the unequal distribution of land. One-third of all agricultural land and forests belonged to a few aristocratic

In the agricultural sector, a program of reform introduced soon after the establishment of the republic was intended to rectify the unequal distribution of land. One-third of all agricultural land and forests belonged to a few aristocratic

landowners—mostly Germans (or Germanized Czechs – e.g. Kinsky, Czernin or Kaunitz) and Hungarians—and the Roman Catholic Church. Half of all holdings were under 20,000 m². The Land Control Act of April 1919 called for the expropriation of all estates exceeding 1.5 square kilometres of arable land or 2.5 square kilometres of land in general (5 square kilometres to be the absolute maximum). Redistribution

was to proceed on a gradual basis; owners would continue in possession in the interim, and compensation was offered.

Table. 1921 ethnonational census

! Regions

! "Czechoslovaks"

(Czechs and Slovaks)

! Germans

! Hungarians

! Rusyns

! Jews

! others

! Total population

|-

| Bohemia

|4 382 788

|2 173 239

|5 476

|2 007

|11 251

|93 757

|6 668 518

|-

| Moravia

|2 048 426

|547 604

|534

|976

|15 335

|46 448

|2 649 323

|-

| Silesia

|296 194

|252 365

|94

|338

|3 681

|49 530

|602 202

|-

| Slovakia

|2 013 792

|139 900

|637 183

|85 644

|70 529

|42 313

|2 989 361

|-

| Carpathian Ruthenia

|19 737

|10 460

|102 144

|372 884

|80 059

|6 760

|592 044

|-

| Czechoslovak Republic

|8 760 937

|3 123 568

|745 431

|461 849

|180 855

|238 080

|13 410 750

|->

National disputes arose due to the fact that the more numerous Czechs

dominated the central government and other national institutions, all of which had their seats in the Bohemian capital Prague. The Slovak middle class had been extremely small in 1919 because Hungarians, Germans and Jews had previously filled most administrative, professional and commercial positions in, and as a result, the Czechs had to be posted to the more backward Slovakia

to take up the administrative and professional posts. The position of the Jewish community, especially in Slovakia was ambiguous and, increasingly, a significant part looked towards Zionism.

Furthermore, most of Czechoslovakia's industry was as well located in Bohemia and Moravia, while most of Slovakia's economy came from agriculture. In Carpatho-Ukraine, the situation was even worse, with basically no industry at all.

Due to Czechoslovakia's centralized political structure, nationalism arose in the non-Czech nationalities, and several parties and movements were formed with the aim of broader political autonomy, like the Sudeten German Party led by Konrad Henlein

and the Hlinka's Slovak People's Party led by Andrej Hlinka

.

The German minority living in Sudetenland

demanded autonomy from the Czech government, claiming they were suppressed and repressed by the Czech government. In the 1935 Parliamentary elections, the newly founded Sudeten German Party under leadership of Konrad Henlein

, financed with Nazi money, won an upset victory, securing over 2/3 of the Sudeten German vote, which worsened the diplomatic relations between the Germans and the Czechs.

Bohemia

Bohemia is a historical region in central Europe, occupying the western two-thirds of the traditional Czech Lands. It is located in the contemporary Czech Republic with its capital in Prague...

, Moravia

Moravia

Moravia is a historical region in Central Europe in the east of the Czech Republic, and one of the former Czech lands, together with Bohemia and Silesia. It takes its name from the Morava River which rises in the northwest of the region...

, Czech Silesia

Czech Silesia

Czech Silesia is an unofficial name of one of the three Czech lands and a section of the Silesian historical region. It is located in the north-east of the Czech Republic, predominantly in the Moravian-Silesian Region, with a section in the northern Olomouc Region...

, Slovakia

Slovakia

The Slovak Republic is a landlocked state in Central Europe. It has a population of over five million and an area of about . Slovakia is bordered by the Czech Republic and Austria to the west, Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east and Hungary to the south...

and Subcarpathian Ruthenia. After 1933 Czechoslovakia remained the only functioning democracy in central and eastern Europe as the other states had authoritarian or autocratic regimes leading them. Under enormous pressure from Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

and the Sudeten German minority living in the country, Czechoslovakia was forced to cede the German-populated Sudetenland

Sudetenland

Sudetenland is the German name used in English in the first half of the 20th century for the northern, southwest and western regions of Czechoslovakia inhabited mostly by ethnic Germans, specifically the border areas of Bohemia, Moravia, and those parts of Silesia being within Czechoslovakia.The...

region to Germany on October 1, 1938, as agreed in the Munich Agreement

Munich Agreement

The Munich Pact was an agreement permitting the Nazi German annexation of Czechoslovakia's Sudetenland. The Sudetenland were areas along Czech borders, mainly inhabited by ethnic Germans. The agreement was negotiated at a conference held in Munich, Germany, among the major powers of Europe without...

as well as southern parts of Slovakia

Slovakia

The Slovak Republic is a landlocked state in Central Europe. It has a population of over five million and an area of about . Slovakia is bordered by the Czech Republic and Austria to the west, Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east and Hungary to the south...

and Subcarpathian Ruthenia to Hungary

Hungary

Hungary , officially the Republic of Hungary , is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is situated in the Carpathian Basin and is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine and Romania to the east, Serbia and Croatia to the south, Slovenia to the southwest and Austria to the west. The...

and the Zaolzie

Zaolzie

Zaolzie is the Polish name for an area now in the Czech Republic which was disputed between interwar Poland and Czechoslovakia. The name means "lands beyond the Olza River"; it is also called Śląsk zaolziański, meaning "trans-Olza Silesia". Equivalent terms in other languages include Zaolší in...

region in Silesia

Silesia

Silesia is a historical region of Central Europe located mostly in Poland, with smaller parts also in the Czech Republic, and Germany.Silesia is rich in mineral and natural resources, and includes several important industrial areas. Silesia's largest city and historical capital is Wrocław...

to Poland

Poland

Poland , officially the Republic of Poland , is a country in Central Europe bordered by Germany to the west; the Czech Republic and Slovakia to the south; Ukraine, Belarus and Lithuania to the east; and the Baltic Sea and Kaliningrad Oblast, a Russian exclave, to the north...

. This effectively ended the First Czechoslovak Republic, which was succeeded by the Second Czechoslovak Republic

Second Czechoslovak Republic

The Second Czechoslovak Republic refers to the second Czechoslovak state that existed from October 1, 1938 to March 14, 1939, thus existing for only 167 days...

.

History

The independence of CzechoslovakiaCzechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia or Czecho-Slovakia was a sovereign state in Central Europe which existed from October 1918, when it declared its independence from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, until 1992...

was proclaimed on October 28, 1918, by the Czechoslovak National Council in Prague

Prague

Prague is the capital and largest city of the Czech Republic. Situated in the north-west of the country on the Vltava river, the city is home to about 1.3 million people, while its metropolitan area is estimated to have a population of over 2.3 million...

. Several ethnic groups and territories with different historical, political, and economic traditions had to be blended into a new state structure. The origin of the First Republic lies in Point 10 of Woodrow Wilson's Fourteen Points: "The peoples of Austria-Hungary, whose place among the nations we wish to see safeguarded and assured, should be accorded the freest opportunity to autonomous development."

The full boundaries of the country and the organization of its government was finally established in the Czechoslovak Constitution of 1920

Czechoslovak Constitution of 1920

After World War I, Czechoslovakia established itself and as a republic and democracy with the establishment of the Constitution of 1920. The constitution was adopted by the National Assembly on 29 February 1920 and replaced the provisional constitution adopted on 13 November 1918.The introduction...

. Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk

Tomáš Masaryk

Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk , sometimes called Thomas Masaryk in English, was an Austro-Hungarian and Czechoslovak politician, sociologist and philosopher, who as an eager advocate of Czechoslovak independence during World War I became the founder and first President of Czechoslovakia, also was...

had been recognized by WWI Allies

Allies of World War I

The Entente Powers were the countries at war with the Central Powers during World War I. The members of the Triple Entente were the United Kingdom, France, and the Russian Empire; Italy entered the war on their side in 1915...

as the leader of the Provisional Czechoslovak Government, and in 1920 he was elected the country's first president. He was re-elected in 1925 and 1929, serving as President until December 14, 1935 when he resigned due to poor health. He was succeeded by Edvard Beneš

Edvard Beneš

Edvard Beneš was a leader of the Czechoslovak independence movement, Minister of Foreign Affairs and the second President of Czechoslovakia. He was known to be a skilled diplomat.- Youth :...

.

Following the Anschluss

Anschluss

The Anschluss , also known as the ', was the occupation and annexation of Austria into Nazi Germany in 1938....

of Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

and Austria

Austria

Austria , officially the Republic of Austria , is a landlocked country of roughly 8.4 million people in Central Europe. It is bordered by the Czech Republic and Germany to the north, Slovakia and Hungary to the east, Slovenia and Italy to the south, and Switzerland and Liechtenstein to the...

in March 1938, Nazi leader Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler was an Austrian-born German politician and the leader of the National Socialist German Workers Party , commonly referred to as the Nazi Party). He was Chancellor of Germany from 1933 to 1945, and head of state from 1934 to 1945...

's next target for annexation was Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia or Czecho-Slovakia was a sovereign state in Central Europe which existed from October 1918, when it declared its independence from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, until 1992...

. His pretext was the privations suffered by ethnic German

Ethnic German

Ethnic Germans historically also ), also collectively referred to as the German diaspora, refers to people who are of German ethnicity. Many are not born in Europe or in the modern-day state of Germany or hold German citizenship...

populations living in Czechoslovakia's northern and western border regions, known collectively as the Sudetenland

Sudetenland

Sudetenland is the German name used in English in the first half of the 20th century for the northern, southwest and western regions of Czechoslovakia inhabited mostly by ethnic Germans, specifically the border areas of Bohemia, Moravia, and those parts of Silesia being within Czechoslovakia.The...

. Their incorporation into Nazi Germany would leave the rest of Czechoslovakia powerless to resist subsequent occupation.

Politics

To a large extent, Czechoslovak democracy was held together by the country's first president, Tomáš MasarykTomáš Masaryk

Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk , sometimes called Thomas Masaryk in English, was an Austro-Hungarian and Czechoslovak politician, sociologist and philosopher, who as an eager advocate of Czechoslovak independence during World War I became the founder and first President of Czechoslovakia, also was...

. As the principal founding father of the republic, Masaryk was regarded similar to the way George Washington

George Washington

George Washington was the dominant military and political leader of the new United States of America from 1775 to 1799. He led the American victory over Great Britain in the American Revolutionary War as commander-in-chief of the Continental Army from 1775 to 1783, and presided over the writing of...

is regarded in the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

. Such universal respect enabled Masaryk to overcome seemingly irresolvable political problems. Even to this day, Masaryk is regarded as the symbol of Czechoslovak democracy.

The Constitution of 1920 approved the provisional constitution of 1918 in its basic features. The Czechoslovak state was conceived as a parliamentary democracy, guided primarily by the National Assembly

National Assembly

National Assembly is either a legislature, or the lower house of a bicameral legislature in some countries. The best known National Assembly, and the first legislature to be known by this title, was that established during the French Revolution in 1789, known as the Assemblée nationale...

, consisting of the Senate

Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a legislature or parliament. There have been many such bodies in history, since senate means the assembly of the eldest and wiser members of the society and ruling class...

and the Chamber of Deputies

Chamber of Deputies

Chamber of deputies is the name given to a legislative body such as the lower house of a bicameral legislature, or can refer to a unicameral legislature.-Description:...

, whose members were to be elected on the basis of universal suffrage

Universal suffrage

Universal suffrage consists of the extension of the right to vote to adult citizens as a whole, though it may also mean extending said right to minors and non-citizens...

. The National Assembly was responsible for legislative initiative and was given supervisory control over the executive

Executive (government)

Executive branch of Government is the part of government that has sole authority and responsibility for the daily administration of the state bureaucracy. The division of power into separate branches of government is central to the idea of the separation of powers.In many countries, the term...

and judiciary

Judiciary

The judiciary is the system of courts that interprets and applies the law in the name of the state. The judiciary also provides a mechanism for the resolution of disputes...

as well. Every seven years it elected the president and confirmed the cabinet appointed by him. Executive power was to be shared by the president and the cabinet; the latter, responsible to the National Assembly, was to prevail. The reality differed somewhat from this ideal, however, during the strong presidencies of Masaryk and his successor, Beneš. The constitution of 1920 provided for the central government to have a high degree of control over local government. From 1928 and 1940, Czechoslovakia was divided into the four "lands" (Czech

Czech language

Czech is a West Slavic language with about 12 million native speakers; it is the majority language in the Czech Republic and spoken by Czechs worldwide. The language was known as Bohemian in English until the late 19th century...

: "země", Slovak

Slovak language

Slovak , is an Indo-European language that belongs to the West Slavic languages .Slovak is the official language of Slovakia, where it is spoken by 5 million people...

: "krajiny"); Bohemia, Moravia-Silesia, Slovakia and Carpathian Ruthenia. Although in 1927 assemblies were provided for Bohemia, Slovakia, and Ruthenia, their jurisdiction was limited to adjusting laws and regulations of the central government to local needs. The central government appointed one third of the members of these assemblies. The constitution identified the "Czechoslovak nation" as the creator and principal constituent of the Czechoslovak state and established Czech and Slovak as official languages. The concept of the Czechoslovak nation was necessary in order to justify the establishment of Czechoslovakia towards the world, because otherwise the statistical majority of the Czechs as compared to Germans would have been rather weak, and there would have been more Germans in the state than Slovaks

Slovaks

The Slovaks, Slovak people, or Slovakians are a West Slavic people that primarily inhabit Slovakia and speak the Slovak language, which is closely related to the Czech language.Most Slovaks today live within the borders of the independent Slovakia...

. National minorities were assured special protection; in districts where they constituted 20% of the population, members of minority groups were granted full freedom to use their language in everyday life, in schools, and in matters dealing with authorities.

Political Parties

Political Parties: A Sociological Study of the Oligarchical Tendencies of Modern Democracy is a book by sociologist Robert Michels, published in 1911 , and first introducing the concept of iron law of oligarchy...

that emerged as the real centers of power. Excluding the period from March 1926 to November 1929, when the coalition did not hold, a coalition of five Czechoslovak parties constituted the backbone of the government: Republican Party of Agricultural and Smallholder People, Czechoslovak Social Democratic Party, Czechoslovak National Socialist Party, Czechoslovak People's Party, and Czechoslovak National Democratic Party. The leaders of these parties became known as the "Pětka

Petka

Petka may refer to:* Pětka or Committee of Five, a Czechoslovak organization* Saint Petka, an ascetic female saint from the Eastern Roman Empire* Petka , a village in Serbia* Petka, Belgrade, a suburb of Lazarevac, Belgrade, Serbia...

" (pron. pyetka) (The Five). The Pětka was headed by Antonin Svehla

Antonín Švehla

Antonín Švehla was a Czechoslovakian politician. He served three terms as the prime minister of Czechoslovakia. He is regarded as one of the most important political figures of the First Czechoslovak Republic; he was the leader of the Agrarian Party, which was dominant within the Pětka, which was...

, who held the office of prime minister for most of the 1920s and designed a pattern of coalition politics that survived until 1938. The coalition's policy was expressed in the slogan "We have agreed that we will agree." German

Germany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

parties also participated in the government in the beginning of 1926. Hungarian

Hungary

Hungary , officially the Republic of Hungary , is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is situated in the Carpathian Basin and is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine and Romania to the east, Serbia and Croatia to the south, Slovenia to the southwest and Austria to the west. The...

s parties, influenced by irredentist propaganda from Hungary, never joined the Czechoslovak government but were not openly hostile:

- The Republican Party of Agricultural and Smallholder People was formed in 1922 from a merger of the Czech Agrarian Party and the Slovak Agrarian Party. Led by Svehla, the new party became the principal voice for the agrarian population, representing mainly peasants with small and medium-sized farms. Svehla combined support for progressive social legislation with a democratic outlook. His party was the core of all government coalitions between 1922 and 1938.

- The Czechoslovak Social Democratic PartyCzech Social Democratic PartyThe Czech Social Democratic Party is a social-democratic political party in the Czech Republic.-History:The Social Democratic Czechoslavonic party in Austria was founded on 7 April 1878 in Austria-Hungary representing the Kingdom of Bohemia in the Austrian parliament...

was considerably weakened when the communists seceded in 1921 to form the Communist Party of CzechoslovakiaCommunist Party of CzechoslovakiaThe Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, in Czech and in Slovak: Komunistická strana Československa was a Communist and Marxist-Leninist political party in Czechoslovakia that existed between 1921 and 1992....

, but by 1929 it had begun to regain its strength. A party of moderation, the Czechoslovak Social Democratic Party declared in favor of parliamentary democracy in 1930. Antonín Hampl was chairman of the party, and Ivan Dérer was the leader of its Slovak branch. - The Czechoslovak National Socialist Party (called the Czech Socialist Party until 1926) was created before World War I when the socialists split from the Social Democratic PartySocial Democratic PartyThe name Social Democratic Party or Social Democrats has been used by a large number of political parties in various countries around the world...

. It rejected class struggle and promoted nationalism. Led by Václav KlofáčVáclav KlofácVáclav Jaroslav Klofáč was a Czech politician and one of the founders of the Czech National Social Party. He was born in 1868 in Německý Brod...

, its membership derived primarily from the lower middle classLower middle classIn developed nations across the world, the lower middle class is a sub-division of the greater middle class. Universally the term refers to the group of middle class households or individuals who have not attained the status of the upper middle class associated with the higher realms of the middle...

, civil servants, and the intelligentsiaIntelligentsiaThe intelligentsia is a social class of people engaged in complex, mental and creative labor directed to the development and dissemination of culture, encompassing intellectuals and social groups close to them...

(including Beneš). - The Czechoslovak People's Party — a fusion of several Catholic parties, groups, and labor unions — developed separately in BohemiaBohemiaBohemia is a historical region in central Europe, occupying the western two-thirds of the traditional Czech Lands. It is located in the contemporary Czech Republic with its capital in Prague...

in 1918 and in the more strongly Catholic MoraviaMoraviaMoravia is a historical region in Central Europe in the east of the Czech Republic, and one of the former Czech lands, together with Bohemia and Silesia. It takes its name from the Morava River which rises in the northwest of the region...

in 1919. In 1922 a common executive committee was formed, headed by Jan ŠrámekJan ŠrámekJan Šrámek was Prime Minister of the Czechoslovak government-in-exile from July 21, 1940 to April 5, 1945. He was the first chairman of the Czechoslovak People's Party and was a Monsignor....

. The Czechoslovak People's Party espoused Christian moral principles and the social encyclicals of Pope Leo XIIIPope Leo XIIIPope Leo XIII , born Vincenzo Gioacchino Raffaele Luigi Pecci to an Italian comital family, was the 256th Pope of the Roman Catholic Church, reigning from 1878 to 1903...

. - The Czechoslovak National Democratic PartyNational Democratic Party (Czechoslovakia)The National Democratic Party was a First Republic right-wing political party in Czechoslovakia. It was founded by Karel Kramář in 1919, after the creation of independent Czechoslovakia from the Austria-Hungary Empire...

developed from a post-World War I merger of the Young Czech PartyYoung Czech PartyThe Young Czech Party was formed in 1874. It initiated the democratization of Czech political parties and led to the establishment of the political base of Czechoslovakia.- Background :...

with other right wingRight-wing politicsIn politics, Right, right-wing and rightist generally refer to support for a hierarchical society justified on the basis of an appeal to natural law or tradition. To varying degrees, the Right rejects the egalitarian objectives of left-wing politics, claiming that the imposition of equality is...

and center parties. Ideologically, it was characterized by national radicalismExtremismExtremism is any ideology or political act far outside the perceived political center of a society; or otherwise claimed to violate common moral standards...

and economic liberalismEconomic liberalismEconomic liberalism is the ideological belief in giving all people economic freedom, and as such granting people with more basis to control their own lives and make their own mistakes. It is an economic philosophy that supports and promotes individual liberty and choice in economic matters and...

. Led by Kramář and Alois RašínAlois RašínAlois Rašín was a Czech economist and politician.Rašín was born into a family of farmers. After gymnasium he continued his schooling with the study of law at the Charles University in Prague. Here he became active in politics, and a leader in the radical students movement...

, the Czechoslovak National Democratic Party became the party of big business, banking, and industry. The party declined in influence after 1920, however.

Foreign policy

Edvard Beneš

Edvard Beneš was a leader of the Czechoslovak independence movement, Minister of Foreign Affairs and the second President of Czechoslovakia. He was known to be a skilled diplomat.- Youth :...

, Czechoslovak foreign minister

Foreign minister

A Minister of Foreign Affairs, or foreign minister, is a cabinet minister who helps form the foreign policy of a sovereign state. The foreign minister is often regarded as the most senior ministerial position below that of the head of government . It is often granted to the deputy prime minister in...

from 1918 to 1935, created the system of alliances that determined the republic's international stance until 1938. A democratic statesman of Western orientation, Beneš relied heavily on the League of Nations

League of Nations

The League of Nations was an intergovernmental organization founded as a result of the Paris Peace Conference that ended the First World War. It was the first permanent international organization whose principal mission was to maintain world peace...

as guarantor of the post war status quo

Status quo

Statu quo, a commonly used form of the original Latin "statu quo" – literally "the state in which" – is a Latin term meaning the current or existing state of affairs. To maintain the status quo is to keep the things the way they presently are...

and the security of newly formed states. He negotiated the Little Entente

Little Entente

The Little Entente was an alliance formed in 1920 and 1921 by Czechoslovakia, Romania and Yugoslavia with the purpose of common defense against Hungarian revision and the prevention of a Habsburg restoration...

(an alliance with Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia refers to three political entities that existed successively on the western part of the Balkans during most of the 20th century....

and Romania

Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central and Southeastern Europe, on the Lower Danube, within and outside the Carpathian arch, bordering on the Black Sea...

) in 1921 to counter Hungarian

Hungary

Hungary , officially the Republic of Hungary , is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is situated in the Carpathian Basin and is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine and Romania to the east, Serbia and Croatia to the south, Slovenia to the southwest and Austria to the west. The...

revanchism

Revanchism

Revanchism is a term used since the 1870s to describe a political manifestation of the will to reverse territorial losses incurred by a country, often following a war or social movement. Revanchism draws its strength from patriotic and retributionist thought and is often motivated by economic or...

and Habsburg

Habsburg

The House of Habsburg , also found as Hapsburg, and also known as House of Austria is one of the most important royal houses of Europe and is best known for being an origin of all of the formally elected Holy Roman Emperors between 1438 and 1740, as well as rulers of the Austrian Empire and...

restoration. He attempted further to negotiate treaties with Britain

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

and France

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

, seeking their promises of assistance in the event of aggression against the small, democratic Czechoslovak Republic

Czechoslovak Republic

Czechoslovak Republic was the official name of Czechoslovakia between 1918 and 1938 and between 1945 and 1960. See*First Czechoslovak Republic*Second Czechoslovak Republic...

. Britain remained intransigent in its isolationist policy, and in 1924 Beneš concluded a separate alliance with France. Beneš's Western policy received a serious blow as early as 1925. The Locarno Pact, which paved the way for Germany

Germany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

's admission to the League of Nations

League of Nations

The League of Nations was an intergovernmental organization founded as a result of the Paris Peace Conference that ended the First World War. It was the first permanent international organization whose principal mission was to maintain world peace...

, guaranteed Germany

Germany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

's western border. French troops were thus left immobilized on the Rhine, making French assistance to Czechoslovakia difficult. In addition, the treaty stipulated that Germany's eastern frontier would remain subject to negotiation. When Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler was an Austrian-born German politician and the leader of the National Socialist German Workers Party , commonly referred to as the Nazi Party). He was Chancellor of Germany from 1933 to 1945, and head of state from 1934 to 1945...

came to power in 1933, fear of German aggression became widespread in eastern Central Europe. Beneš ignored the possibility of a stronger Central European alliance system, remaining faithful to his Western policy. He did, however, seek the participation of the Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

in an alliance to include France

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

. (Beneš's earlier attitude towards the Soviet regime had been one of caution.) In 1935 the Soviet Union signed treaties with France and Czechoslovakia. In essence, the treaties provided that the Soviet Union would come to Czechoslovakia's aid only if French assistance came first.

In 1935, when Beneš succeeded Masaryk as president, and Prime Minister Milan Hodža took over the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Hodža's efforts to strengthen alliances in Central Europe came too late. In February 1936 the foreign ministry came under the direction of Kamil Krofta

Kamil Krofta

Kamil Krofta was Czech historian and diplomat.-Life and career:Born and schooled in Plzeň, he studied philosophy in Prague starting in 1894, then from 1896 to 1899 in Vienna. From 1899 to 1901 he studied in the Vatican Archives. From 1901 he worked at the National Archives...

, an adherent of Beneš's line.

Economy

The new nation had a population of over 13.5 million. It had inherited 70 to 80% of all the industry of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, including the porcelainPorcelain

Porcelain is a ceramic material made by heating raw materials, generally including clay in the form of kaolin, in a kiln to temperatures between and...

and glass industries and the sugar refineries; more than 40% of all its distilleries and breweries; the Škoda Works

Škoda Works

Škoda Works was the largest industrial enterprise in Austro-Hungary and later in Czechoslovakia, one of its successor states. It was also one of the largest industrial conglomerates in Europe in the 20th century...

of Pilsen (Plzeň), which produced armaments, locomotives, automobiles, and machinery; and the chemical industry of northern Bohemia

Bohemia

Bohemia is a historical region in central Europe, occupying the western two-thirds of the traditional Czech Lands. It is located in the contemporary Czech Republic with its capital in Prague...

. Seventeen percent of all Hungarian

Kingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary comprised present-day Hungary, Slovakia and Croatia , Transylvania , Carpatho Ruthenia , Vojvodina , Burgenland , and other smaller territories surrounding present-day Hungary's borders...

industry that had developed in Slovakia during the late 19th century also fell to the republic. Czechoslovakia was one of the world's 10 most industrialized states.

The Czech lands were far more industrialized than Slovakia. In Bohemia

Bohemia

Bohemia is a historical region in central Europe, occupying the western two-thirds of the traditional Czech Lands. It is located in the contemporary Czech Republic with its capital in Prague...

, Moravia

Moravia

Moravia is a historical region in Central Europe in the east of the Czech Republic, and one of the former Czech lands, together with Bohemia and Silesia. It takes its name from the Morava River which rises in the northwest of the region...

, and Silesia

Silesia

Silesia is a historical region of Central Europe located mostly in Poland, with smaller parts also in the Czech Republic, and Germany.Silesia is rich in mineral and natural resources, and includes several important industrial areas. Silesia's largest city and historical capital is Wrocław...

, 39% of the population was employed in industry and 31% in agriculture and forestry

Forestry

Forestry is the interdisciplinary profession embracing the science, art, and craft of creating, managing, using, and conserving forests and associated resources in a sustainable manner to meet desired goals, needs, and values for human benefit. Forestry is practiced in plantations and natural stands...

. Most light and heavy industry was located in the Sudetenland

Sudetenland

Sudetenland is the German name used in English in the first half of the 20th century for the northern, southwest and western regions of Czechoslovakia inhabited mostly by ethnic Germans, specifically the border areas of Bohemia, Moravia, and those parts of Silesia being within Czechoslovakia.The...

and was owned by Germans and controlled by German-owned banks. Czechs

Czech people

Czechs, or Czech people are a western Slavic people of Central Europe, living predominantly in the Czech Republic. Small populations of Czechs also live in Slovakia, Austria, the United States, the United Kingdom, Chile, Argentina, Canada, Germany, Russia and other countries...

controlled only 20 to 30% of all industry. In Slovakia 17.1% of the population was employed in industry, and 60.4% worked in agriculture and forestry. Only 5% of all industry in Slovakia was in Slovak

Slovaks

The Slovaks, Slovak people, or Slovakians are a West Slavic people that primarily inhabit Slovakia and speak the Slovak language, which is closely related to the Czech language.Most Slovaks today live within the borders of the independent Slovakia...

hands. Carpathian Ruthenia

Carpathian Ruthenia

Carpathian Ruthenia is a region in Eastern Europe, mostly located in western Ukraine's Zakarpattia Oblast , with smaller parts in easternmost Slovakia , Poland's Lemkovyna and Romanian Maramureş.It is...

was essentially without industry.

Aristocracy (class)

The aristocracy are people considered to be in the highest social class in a society which has or once had a political system of Aristocracy. Aristocrats possess hereditary titles granted by a monarch, which once granted them feudal or legal privileges, or deriving, as in Ancient Greece and India,...

landowners—mostly Germans (or Germanized Czechs – e.g. Kinsky, Czernin or Kaunitz) and Hungarians—and the Roman Catholic Church. Half of all holdings were under 20,000 m². The Land Control Act of April 1919 called for the expropriation of all estates exceeding 1.5 square kilometres of arable land or 2.5 square kilometres of land in general (5 square kilometres to be the absolute maximum). Redistribution

Redistribution (economics)

Redistribution of wealth is the transfer of income, wealth or property from some individuals to others caused by a social mechanism such as taxation, monetary policies, welfare, nationalization, charity, divorce or tort law. Most often it refers to progressive redistribution, from the rich to the...

was to proceed on a gradual basis; owners would continue in possession in the interim, and compensation was offered.

Ethnic groups

! "Czechoslovaks"

(Czechs and Slovaks)

! Germans

! Hungarians

! Rusyns

! Jews

History of the Jews in Czechoslovakia

-Demography:table 1. Jewish population by religion in CzechoslovakiaTable 2. Declared Nationality of Jews in Czechoslovakia-Holocaust:For the Czechs of the Protectorate Bohemia and Moravia, German occupation was a period of brutal oppression. The Jewish population of Bohemia and Moravia was...

! others

! Total population

|-

| Bohemia

Bohemia

Bohemia is a historical region in central Europe, occupying the western two-thirds of the traditional Czech Lands. It is located in the contemporary Czech Republic with its capital in Prague...

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|-

| Moravia

Moravia

Moravia is a historical region in Central Europe in the east of the Czech Republic, and one of the former Czech lands, together with Bohemia and Silesia. It takes its name from the Morava River which rises in the northwest of the region...

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|-

| Silesia

Zaolzie

Zaolzie is the Polish name for an area now in the Czech Republic which was disputed between interwar Poland and Czechoslovakia. The name means "lands beyond the Olza River"; it is also called Śląsk zaolziański, meaning "trans-Olza Silesia". Equivalent terms in other languages include Zaolší in...

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|-

| Slovakia

Slovakia

The Slovak Republic is a landlocked state in Central Europe. It has a population of over five million and an area of about . Slovakia is bordered by the Czech Republic and Austria to the west, Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east and Hungary to the south...

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|-

| Carpathian Ruthenia

Carpathian Ruthenia

Carpathian Ruthenia is a region in Eastern Europe, mostly located in western Ukraine's Zakarpattia Oblast , with smaller parts in easternmost Slovakia , Poland's Lemkovyna and Romanian Maramureş.It is...

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|-

| Czechoslovak Republic

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|->

National disputes arose due to the fact that the more numerous Czechs

Czech people

Czechs, or Czech people are a western Slavic people of Central Europe, living predominantly in the Czech Republic. Small populations of Czechs also live in Slovakia, Austria, the United States, the United Kingdom, Chile, Argentina, Canada, Germany, Russia and other countries...

dominated the central government and other national institutions, all of which had their seats in the Bohemian capital Prague. The Slovak middle class had been extremely small in 1919 because Hungarians, Germans and Jews had previously filled most administrative, professional and commercial positions in, and as a result, the Czechs had to be posted to the more backward Slovakia

Slovakia

The Slovak Republic is a landlocked state in Central Europe. It has a population of over five million and an area of about . Slovakia is bordered by the Czech Republic and Austria to the west, Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east and Hungary to the south...

to take up the administrative and professional posts. The position of the Jewish community, especially in Slovakia was ambiguous and, increasingly, a significant part looked towards Zionism.

Furthermore, most of Czechoslovakia's industry was as well located in Bohemia and Moravia, while most of Slovakia's economy came from agriculture. In Carpatho-Ukraine, the situation was even worse, with basically no industry at all.

Due to Czechoslovakia's centralized political structure, nationalism arose in the non-Czech nationalities, and several parties and movements were formed with the aim of broader political autonomy, like the Sudeten German Party led by Konrad Henlein

Konrad Henlein

Konrad Ernst Eduard Henlein was a leading pro-Nazi ethnic German politician in Czechoslovakia and leader of Sudeten German separatists...

and the Hlinka's Slovak People's Party led by Andrej Hlinka

Andrej Hlinka

Andrej Hlinka was a Slovak politician and Catholic priest, one of the most important Slovak public activists in Czechoslovakia before Second World War...

.

The German minority living in Sudetenland

Sudetenland

Sudetenland is the German name used in English in the first half of the 20th century for the northern, southwest and western regions of Czechoslovakia inhabited mostly by ethnic Germans, specifically the border areas of Bohemia, Moravia, and those parts of Silesia being within Czechoslovakia.The...

demanded autonomy from the Czech government, claiming they were suppressed and repressed by the Czech government. In the 1935 Parliamentary elections, the newly founded Sudeten German Party under leadership of Konrad Henlein

Konrad Henlein

Konrad Ernst Eduard Henlein was a leading pro-Nazi ethnic German politician in Czechoslovakia and leader of Sudeten German separatists...

, financed with Nazi money, won an upset victory, securing over 2/3 of the Sudeten German vote, which worsened the diplomatic relations between the Germans and the Czechs.

See also

- Germans in Czechoslovakia (1918-1938)Germans in Czechoslovakia (1918-1938)From 1918 to 1938, after the breakup of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, more than 3 million ethnic Germans were living in what became the Czech lands of the newly created state of Czechoslovakia. Ethnic Germans had lived in Bohemia, a part of the Holy Roman Empire, since the 14th century , mostly in...

- Hungarians in SlovakiaHungarians in SlovakiaHungarians in Slovakia are the largest ethnic minority of the country, numbering 520,528 people or 9.7% of population . They are concentrated mostly in the southern part of the country, near the border with Hungary...

- Polish minority in the Czech RepublicPolish minority in the Czech RepublicThe Polish minority in the Czech Republic is a Polish national minority living mainly in the Zaolzie region of western Cieszyn Silesia. The Polish community is the only national minority in the Czech Republic that is linked to a specific geographical area. Zaolzie is located in the north-eastern...

- Slovaks in Czechoslovakia (1918-1938)Slovaks in Czechoslovakia (1918-1938)Whereas Czechs wished to create a Czechoslovak nation, Slovaks sought a federal republic in 1918. The new Czechoslovak republic , with its predominantly Czech administrative apparatus, hardly responded to Slovak aspirations for at least some form of autonomy...

- Ukrainians in Czechoslovakia (1918–1938)

- Jews in Slovakia