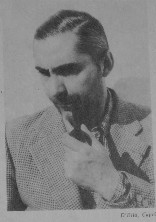

Curzio Malaparte

Encyclopedia

Italy

Italy , officially the Italian Republic languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Italy's official name is as follows:;;;;;;;;), is a unitary parliamentary republic in South-Central Europe. To the north it borders France, Switzerland, Austria and...

journalist, dramatist, short-story writer, novelist and diplomat

Diplomat

A diplomat is a person appointed by a state to conduct diplomacy with another state or international organization. The main functions of diplomats revolve around the representation and protection of the interests and nationals of the sending state, as well as the promotion of information and...

. His chosen surname

Surname

A surname is a name added to a given name and is part of a personal name. In many cases, a surname is a family name. Many dictionaries define "surname" as a synonym of "family name"...

, which he used from 1925, means "evil/wrong side" and is a play on Napoleon's family name "Bonaparte

Bonaparte

The House of Bonaparte is an imperial and royal European dynasty founded by Napoleon I of France in 1804, a French military leader who rose to notability out of the French Revolution and transformed the French Republic into the First French Empire within five years of his coup d'état...

" which means, in Italian, "good side".

Biography

Born in PratoPrato

Prato is a city and comune in Tuscany, Italy, the capital of the Province of Prato. The city is situated at the foot of Monte Retaia , the last peak in the Calvana chain. The lowest altitude in the comune is 32 m, near the Cascine di Tavola, and the highest is the peak of Monte Cantagrillo...

, Tuscany, to a Lombard

Lombardy

Lombardy is one of the 20 regions of Italy. The capital is Milan. One-sixth of Italy's population lives in Lombardy and about one fifth of Italy's GDP is produced in this region, making it the most populous and richest region in the country and one of the richest in the whole of Europe...

mother and a German

Ethnic German

Ethnic Germans historically also ), also collectively referred to as the German diaspora, refers to people who are of German ethnicity. Many are not born in Europe or in the modern-day state of Germany or hold German citizenship...

father, he was educated at Collegio Cicognini and at the La Sapienza University

University of Rome La Sapienza

The Sapienza University of Rome, officially Sapienza – Università di Roma, formerly known as Università degli studi di Roma "La Sapienza", is a coeducational, autonomous state university in Rome, Italy...

of Rome. In 1918 he started his career as a journalist.

Malaparte fought in World War I, earning a captaincy in the Fifth Alpine Regiment

Alpini

The Alpini, , are the elite mountain warfare soldiers of the Italian Army. They are currently organized in two operational brigades, which are subordinated to the Alpini Corps Command. The singular is Alpino ....

and several decorations for valor, and in 1922 took part in Benito Mussolini

Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini was an Italian politician who led the National Fascist Party and is credited with being one of the key figures in the creation of Fascism....

's March on Rome

March on Rome

The March on Rome was a march by which Italian dictator Benito Mussolini's National Fascist Party came to power in the Kingdom of Italy...

. In 1924, he founded the Roman periodical La Conquista dello Stato ("The Conquest of the State", a title that would inspire Ramiro Ledesma Ramos

Ramiro Ledesma Ramos

Ramiro Ledesma Ramos was a Spanish national syndicalist politician, essayist, and journalist.-Early life:...

' La Conquista del Estado

La Conquista del Estado

La Conquista del Estado was a publication in Spain. It was launched in 1931 by Ramiro Ledesma Ramos.The first issue, issued on March 14, 1931, contained a manifesto in which National Syndicalism was elaborated...

). As a member of the Partito Nazionale Fascista, he founded several periodicals and contributed essays and articles to others, as well as writing numerous books, starting from the early 1920s, and directing two metropolitan newspapers.

In 1926 he founded with Massimo Bontempelli

Massimo Bontempelli

Massimo Bontempelli was an Italian poet, playwright, and novelist. He was influential in developing and promoting the literary style known as magical realism.-Life:...

(1878–1960) the literary quarterly "900"

"900", Cahiers d'Italie et d'Europe

"900", Cahiers d'Italie et d'Europe was an Italian magazine published for the first time in November 1926, directed by Massimo Bontempelli with Curzio Malaparte as co-director...

. Later he became a co-editor of Fiera Letteraria (1928–31), and an editor of La Stampa

La Stampa

La Stampa is one of the best-known, most influential and most widely sold Italian daily newspapers. Published in Turin, it is distributed in Italy and other European nations. The current owner is the Fiat Group.-History:...

in Turin

Turin

Turin is a city and major business and cultural centre in northern Italy, capital of the Piedmont region, located mainly on the left bank of the Po River and surrounded by the Alpine arch. The population of the city proper is 909,193 while the population of the urban area is estimated by Eurostat...

. His polemical war novel-essay, Viva Caporetto! (1921), criticized corrupt Rome and the Italian upper classes as the real enemy (the book was forbidden because it offended the Regio Esercito). In Tecnica del Colpo di Stato (1931) Malaparte attacked both Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler was an Austrian-born German politician and the leader of the National Socialist German Workers Party , commonly referred to as the Nazi Party). He was Chancellor of Germany from 1933 to 1945, and head of state from 1934 to 1945...

and Mussolini. This led to Malaparte being stripped of his National Fascist Party

National Fascist Party

The National Fascist Party was an Italian political party, created by Benito Mussolini as the political expression of fascism...

membership and sent to internal exile

Exile

Exile means to be away from one's home , while either being explicitly refused permission to return and/or being threatened with imprisonment or death upon return...

from 1933 to 1938 on the island of Lipari

Lipari

Lipari is the largest of the Aeolian Islands in the Tyrrhenian Sea off the north coast of Sicily, and the name of the island's main town. It has a permanent population of 11,231; during the May–September tourist season, its population may reach up to 20,000....

.

He was freed on the personal intervention of Mussolini's son-in-law and heir apparent Galeazzo Ciano

Galeazzo Ciano

Gian Galeazzo Ciano, 2nd Count of Cortellazzo and Buccari was an Italian Minister of Foreign Affairs and Benito Mussolini's son-in-law. In early 1944 Count Ciano was shot by firing squad at the behest of his father-in-law, Mussolini under pressure from Nazi Germany.-Early life:Ciano was born in...

. Mussolini's regime arrested Malaparte again in 1938, 1939, 1941, and 1943 and imprisoned him in Rome's infamous jail Regina Coeli. During that time (1938–41) he built a house, known as the Casa Malaparte

Casa Malaparte

Casa Malaparte is a house on Punta Massullo, on the eastern side of the Isle of Capri, Italy. It is one of the best examples of Italian modern and contemporary architecture....

, on Capo Massullo, on the Isle of Capri

Capri

Capri is an Italian island in the Tyrrhenian Sea off the Sorrentine Peninsula, on the south side of the Gulf of Naples, in the Campania region of Southern Italy...

. It was a key location in Jean-Luc Godard

Jean-Luc Godard

Jean-Luc Godard is a French-Swiss film director, screenwriter and film critic. He is often identified with the 1960s French film movement, French Nouvelle Vague, or "New Wave"....

's film, Le Mepris, (Eng: Contempt), starring Brigitte Bardot

Brigitte Bardot

Brigitte Anne-Marie Bardot is a French former fashion model, actress, singer and animal rights activist. She was one of the best-known sex-symbols of the 1960s.In her early life, Bardot was an aspiring ballet dancer...

and Fritz Lang

Fritz Lang

Friedrich Christian Anton "Fritz" Lang was an Austrian-American filmmaker, screenwriter, and occasional film producer and actor. One of the best known émigrés from Germany's school of Expressionism, he was dubbed the "Master of Darkness" by the British Film Institute...

, based on an Alberto Moravia

Alberto Moravia

Alberto Moravia, born Alberto Pincherle was an Italian novelist and journalist. His novels explored matters of modern sexuality, social alienation, and existentialism....

novel.

Shortly after his time in jail he published books of magical realist autobiographical short stories, which culminated in the stylistic prose of Donna Come Me (Woman Like Me) (1940).

His remarkable knowledge of Europe and its leaders is based upon his experience as a correspondent and in the Italian diplomatic service. In 1941 he was sent to cover the Eastern Front

Eastern Front (World War II)

The Eastern Front of World War II was a theatre of World War II between the European Axis powers and co-belligerent Finland against the Soviet Union, Poland, and some other Allies which encompassed Northern, Southern and Eastern Europe from 22 June 1941 to 9 May 1945...

as a correspondent for Corriere della Sera

Corriere della Sera

The Corriere della Sera is an Italian daily newspaper, published in Milan.It is among the oldest and most reputable Italian newspapers. Its main rivals are Rome's La Repubblica and Turin's La Stampa.- History :...

. The articles he sent back from the Ukrainian Fronts, many of which were suppressed, were collected in 1943 and brought out under the title Il Volga nasce in Europa ("The Volga Rises in Europe"). Also, this experience provided the basis for his two most famous books, Kaputt (1944) and The Skin (1949).

Kaputt, his novelistic account of the war, surreptitiously written, presents the conflict from the point of view of those doomed to lose it. Malaparte's account is marked by lyrical observations, as when he encounters a detachment of Wehrmacht

Wehrmacht

The Wehrmacht – from , to defend and , the might/power) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the Heer , the Kriegsmarine and the Luftwaffe .-Origin and use of the term:...

soldiers fleeing a Ukrainian

Ukrainian SSR

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic or in short, the Ukrainian SSR was a sovereign Soviet Socialist state and one of the fifteen constituent republics of the Soviet Union lasting from its inception in 1922 to the breakup in 1991...

battlefield:

When Germans become afraid, when that mysterious German fear begins to creep into their bones, they always arouse a special horror and pity. Their appearance is miserable, their cruelty sad, their courage silent and hopeless.

According to D. Moore's editorial note, in The Skin:

Malaparte extends the great fresco of European society he began in Kaputt. There the scene was Eastern Europe, here it is Italy during the years from 1943 to 1945; instead of Germans, the invaders are the American armed forcesUnited States ArmyThe United States Army is the main branch of the United States Armed Forces responsible for land-based military operations. It is the largest and oldest established branch of the U.S. military, and is one of seven U.S. uniformed services...

. In all the literature that derives from the Second World War, there is no other book that so brilliantly or so woundingly present triumphant American innocence against the background of the European experience of destruction and moral collapse.

The book was condemned by the Roman Catholic Church, and placed on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum

Index Librorum Prohibitorum

The Index Librorum Prohibitorum was a list of publications prohibited by the Catholic Church. A first version was promulgated by Pope Paul IV in 1559, and a revised and somewhat relaxed form was authorized at the Council of Trent...

. A movie was made out of it.

From November 1943 to March 1946 he was attached to the American High Command in Italy as an Italian Liaison Officer. Articles by Curzio Malaparte have appeared in many literary periodicals of note in France, the United Kingdom, Italy and the United States.

After the war, Malaparte's political sympathies veered to the left, and he became member of the Italian Communist Party

Italian Communist Party

The Italian Communist Party was a communist political party in Italy.The PCI was founded as Communist Party of Italy on 21 January 1921 in Livorno, by seceding from the Italian Socialist Party . Amadeo Bordiga and Antonio Gramsci led the split. Outlawed during the Fascist regime, the party played...

. In 1947 Malaparte settled in Paris and wrote dramas without much success. His play Du Côté de chez Proust was based on the life of Marcel Proust

Marcel Proust

Valentin Louis Georges Eugène Marcel Proust was a French novelist, critic, and essayist best known for his monumental À la recherche du temps perdu...

, and Das Kapital was a portrait of Karl Marx

Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx was a German philosopher, economist, sociologist, historian, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. His ideas played a significant role in the development of social science and the socialist political movement...

. Cristo Proibito

The Forbidden Christ

The Forbidden Christ is a 1951 Italian drama film directed by Curzio Malaparte.-Cast:* Raf Vallone - Bruno Baldi* Rina Morelli - Mother Baldi* Alain Cuny - Antonio* Anna-Maria Ferrero - Maria* Elena Varzi - Nella* Gino Cervi - The Sexton...

("Forbidden Christ") was Malaparte's moderately successful film—which he wrote, directed, and scored in 1950. It won the "City of Berlin" special prize at the 1st Berlin International Film Festival

1st Berlin International Film Festival

The 1st annual Berlin International Film Festival was held from June 6 to June 17, 1951. The opening film was Alfred Hitchcock's Rebecca.At this very first Berlin Festival, the Golden Bear award was introduced, and it was awarded to the best film in each of five categories: drama, comedy, crime or...

in 1951. In the story, a war veteran returns to his village to avenge the death of his brother, shot by the Germans. It was released in the United States in 1953 as Strange Deception and voted among the five best foreign films by National Board Of Review

National Board of Review of Motion Pictures

The National Board of Review of Motion Pictures was founded in 1909 in New York City, just 13 years after the birth of cinema, to protest New York City Mayor George B. McClellan, Jr.'s revocation of moving-picture exhibition licenses on Christmas Eve 1908. The mayor believed that the new medium...

.

He also produced the variety show Sexophone and planned to cross the United States on bicycle. Just before his death, Malaparte completed the treatment of another film, Il Compagno P. After the establishment of the People's Republic of China in 1949, Malaparte became interested in the Maoist

Maoism

Maoism, also known as the Mao Zedong Thought , is claimed by Maoists as an anti-Revisionist form of Marxist communist theory, derived from the teachings of the Chinese political leader Mao Zedong . Developed during the 1950s and 1960s, it was widely applied as the political and military guiding...

version of Communism, but his journey to China was cut short by illness, and he was flown back to Rome. Io in Russia e in Cina, his journal of the events, was published posthumously in 1958. Malaparte's final book, Maledetti Toscani, his attack on bourgeois

Bourgeoisie

In sociology and political science, bourgeoisie describes a range of groups across history. In the Western world, between the late 18th century and the present day, the bourgeoisie is a social class "characterized by their ownership of capital and their related culture." A member of the...

culture, appeared in 1956.

Shortly after the publication of this book, he became a Catholic. He died from lung cancer on 19 July 1957.

Main writings

- Viva Caporetto! (1921, aka La rivolta dei santi maledetti)

- Tecnica del colpo di Stato (1931) translated as Coup D'etat: The Technique of revolution, E. P. Dutton & Co., Inc., 1932

- Donna Come Me (1940) translated as Woman Like Me, Troubador Italian Studies, 2006 ISBN 1-905237-84-7

- The Volga Rises in Europe (1943) ISBN 1-84158-096-1

- Kaputt (1944) ISBN 0-8101-1341-4

- La Pelle (1949) translated as The Skin ISBN 0-8101-1572-7

- Du Côté de chez Proust (1951)

- Maledetti toscani (1956) translated as Those Cursed Tuscans, Ohio University PressOhio University PressOhio University Press is part of Ohio University. It publishes under its own name and the imprint Swallow Press....

, 1964

Secondary Bibliography

- Malaparte: A House Like Me by Michael McDonough, 1999, ISBN 0-609-60378-7)

- The Appeal of FascismThe Appeal of FascismThe Appeal of Fascism: A Study of Intellectuals and Fascism 1919-1945 is a 1971 book by Alastair Hamilton. It examines poets, philosophers, artists, and writers with fascist sympathies and convictions in Italy, Germany, France, and England....

: A Study of Intellectuals and Fascism 1919–1945 by Alastair Hamilton (London, 1971, ISBN 0-218-51426-3) - Kaputt by Curzio Malaparte, E. P. Dutton and Comp., Inc., New York, 1946 (biographical note on the book cover)

- Curzio Malaparte The Skin, Northwestern University Press, Evanston, 1997 (D. Moore editorial note on the back cover)

- Curzio Malaparte: The Narrative Contract Strained by William Hope, Troubador Publishing Ltd, 2000 ISBN 1-899293-22-1, 9781899293223

- European memories of the Second World War by Helmut Peitsch (editor) Berghahn Books, 1999 ISBN 1-57181-936-3, 9781571819369 Chapter Changing Identities Through Memory: Malaparte's Self-figuratios in Kaputt by Charles Burdett, p. 110–119

- Malaparte Zwischen Erdbeben by Jobst Welge, Eichborn Verlag, Frankfurt-am-Main 2007 ISBN 3-8218-4586-9