Collective leadership

Encyclopedia

Collective leadership or Collectivity of leadership , was considered an ideal form of governance in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

(USSR). Its main task was to distribute powers and functions among the Politburo, the Central Committee

, and the Council of Ministers to hinder any attempts to create a one-man dominance

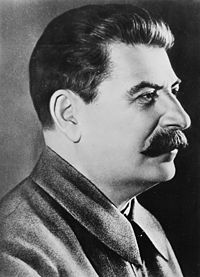

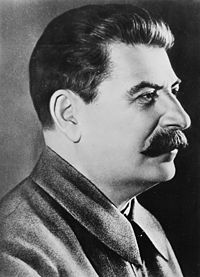

over the Soviet political system by a Soviet leader, such as that seen under Joseph Stalin

's rule. On the national level, the heart of the collective leadership was officially the Central Committee of the Communist Party

. Collective leadership is characterised by limiting the powers of the General Secretary

and the Chairman

of the Council of Ministers as related to other offices by enhancing the powers of collective bodies, such as the Politburo.

Vladimir Lenin

was, according to Soviet literature, the perfect example of a leader ruling in favour of the collective. Stalin's rule was characterised by one-man dominance, which was a deep breach of inner-party democracy

and collective leadership; this made his leadership highly controversial in the Soviet Union following his death in 1953. At the 20th Party Congress, Stalin's reign was criticised as the "cult of the individual". Nikita Khrushchev

, Stalin's successor, supported the ideal of collective leadership but only ruled in a collective fashion when it suited him. In 1964, Khrushchev was ousted due to his disregard of collective leadership and was replaced in his posts by Leonid Brezhnev

as First Secretary and by Alexei Kosygin as Premier. Collective leadership was strengthened during the Brezhnev years and the later reigns of Yuri Andropov

and Konstantin Chernenko

. Mikhail Gorbachev

's reforms helped spawn factionalism within the Soviet leadership, and members of Gorbachev's faction openly disagreed with him on key issues. The factions usually disagreed on how little or how much reform was needed to rejuvenate the Soviet system.

, the first Soviet leader, thought that only collective leadership could protect the Party from serious mistakes. Joseph Stalin

promoted these values; however, instead of creating a new collective leadership, he created an autocratic leadership

centered around himself. After Stalin's death, his successors, who were vying for control over the Soviet leadership, promoted the values of collective leadership. Georgy Malenkov

, Lavrentiy Beria

and Vyacheslav Molotov

formed a collective leadership immediately after Stalin's death, but it collapsed when Malenkov and Molotov deceived Beria. After the arrest of Beria, Nikita Khrushchev

proclaimed that collective leadership was the "supreme principle of our Party". He further stated that only decisions approved by the Central Committee

(CC) could ensure good leadership for the party and the country. In reality, however, Khrushchev promoted these ideas so that he could win enough support to remove his opponents from power, the most notable of whom was Premier Malenkov in 1955.

Stalin's rule was criticised during the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

as a "cult of the individual". He was accused of reducing the Party's activities and putting an end to Party democracy

among others. In the three years following Stalin's death, the Central Committee and the Presidium (Politburo) worked consistently to uphold the collective leadership lost under Stalin. Khrushchev's rule as First Secretary remained highly controversial throughout his rule in the Party leadership. The first attempt to depose Khrushchev came in 1957, when the Anti-Party Group

accused him of individualistic leadership. The coup failed, but Khrushchev's position was drastically weakened. However, Khrushchev continued to call his rule as a rule of the collective even after becoming Chairman

of the Council of Ministers (Premier of the Soviet Union) by replacing Nikolai Bulganin

. At the 22nd Party Congress, Khrushchev declared an end to the dictatorship of the proletariat

and the establishment of the All-People's State. The All-People's State would strengthen collective decision-making within such government institutions as, for instance, the Supreme Soviet. This concept meant that everyone had the opportunity to become active in government leadership politics on a rotational basis, and that one-third of the Soviets'

representatives would be replaced with new members at every election

. Some state administrative functions and powers were to be moved to other public institutions and democratic rule would also be expanded under the All-People's State. However, in 1967 the new Soviet leadership revised the definition, and created a new definition in which All-People's State simply meant an extension of the dictatorship of the proletariat.

's one-man dominance

and the growing cult of personality in the People's Republic of China

, began an aggressive campaign against Khrushchev in 1963. This campaign culminated in 1964 with the replacement of Khrushchev in his offices of First Secretary by Leonid Brezhnev

and of Chairman of the Council of Ministers by Alexei Kosygin. Brezhnev and Kosygin, along with Mikhail Suslov

, Andrei Kirilenko

and Anastas Mikoyan

(replaced in 1965 by Nikolai Podgorny

), were elected to their respective offices to form and lead a functioning collective leadership. One of the reasons for Khrushchev's ousting, as Suslov told him, was his violation of collective leadership. With Khrushchev's removal, collective leadership was again praised by the Soviet media, and it was claimed to be a return to "Leninist norms of Party life

". At the plenum which ousted Khrushchev, the Central Committee forbade any single individual to hold the office of General Secretary

and Premier simultaneously.

The leadership was usually referred to as the "Brezhnev–Kosygin" leadership, instead of the collective leadership, by First World

medias. At first, there was no clear leader of the collective leadership, and Kosygin was the chief economic administrator, whereas Brezhnev was primarily responsible for the day-to-day management of the party and internal affairs. Kosygin's position was later weakened when he introduced a reform in 1965

that attempted to decentralise the Soviet economy. The reform led to a backlash, with Kosygin losing supporters because many top officials took an increasingly anti-reformist stance due to the Prague Spring

of 1968. As the years passed, Brezhnev was given more and more prominence, and by the 1970s he had even created a "Secretariat of the General Secretary" to strengthen his position within the Party. At the 25th Party Congress, Brezhnev was, according to an anonymous historian, praised in a way that exceeded the praise accorded to Khrushchev before his removal. Brezhnev was able to retain the Politburo's support by not introducing the same sweeping reform measures as seen during Khrushchev's rule. As noted by foreign officials, Brezhnev felt "obliged" to discuss unanticipated proposals with the Politburo before responding to them.

did not alter the balance the power

in any radical fashion, and Yuri Andropov

and Konstantin Chernenko

were obliged by protocol to rule the country in the very same fashion as Brezhnev. When Mikhail Gorbachev was elected to the position of General Secretary in March 1985, some observers wondered if he could be the leader who could overcome the restraints of the collective leadership. Gorbachev's reform agenda had succeeded in altering the Soviet political system

for good; however, this change created him more enemies. Many of Gorbachev's closest allies disagreed with him on what reforms were needed, or how radical they were to be. The claim that the Secretariat was the Party's "centre of power" was proven false in 1988 when it was shown that Yegor Ligachev

chaired its meetings, rather than Gorbachev.

and not the Politburo was the heart of collective leadership at the national level. At a sub-national level, all Party and Government organs were to work together to ensure collective leadership instead of only the Central Committee. However, as with many other ideological theses, the definition of collective leadership was applied "flexibly to a variety of situations". Making Vladimir Lenin

the example of a ruler ruling in favour of a collective can be seen as proof of this "flexibility". In some Soviet ideological drafts, collective leadership can be compared to collegial leadership

instead of a leadership of the collective. In accordance with a Soviet textbook, collective leadership was:

In contrast to fascism

, which advocates one-man dominance

, Leninism

advocates inner-Party democratic collective leadership. Hence, the ideological justification of collective leadership in the Soviet Union was easy to justify. The physical insecurity of the political leadership under Stalin, and the political insecurity that existed during Khrushchev's reign, strengthened the political leadership's will to ensure a rule of the collective, and not that of the individual. Collective leadership was a value that was highly esteemed during Stalin and Khrushchev's reigns, but it was violated in practice.

Richard Löwenthal

Richard Löwenthal

, a German professor, believed that the Soviet Union had evolved from being a totalitarian state under the rule of Joseph Stalin

into a system that he called "post-totalitarian authoritarianism", or "authoritarian bureaucratic oligarchy", in which the Soviet state remained omnipotent in theory and highly authoritarian in practice. However, it did considerably reduce the scale of repression and allowed a much greater level of pluralism into public life. In a 1960 paper, Löwenthal wrote that one-man leadership was "the normal rule of line in a one-party state". The majority of First World

observers tended to agree with Löwenthal on the grounds that a collective leadership in an authoritarian state was "inherently unworkable" in practice, claiming that a collective leadership would sooner or later always give in for one-man rule. In a different interpretation, the Soviet Union was seen to go into periods of "oligarchy" and "limited-personal rule". Oligarchy, in the sense that no individual could "prevent the adoption of policies in which he may be opposed", was seen as an unstable form of government. "Limited-personal rule", in contrast with Joseph Stalin

's "personal rule", was a type of governance in which major policy-making decision could not be made without the consent of the leader, while the leader had to tolerate some opposition to his policies and to his leadership in general.

The historian T. H. Rigby claimed that the Soviet leadership was setting up checks and balances within the Party to ensure the stability of collective leadership. One anonymous historian went so far as to claim that collective leadership was bound to triumph in any future Soviet political system. Professor Jerome Gilison argued that collective leadership had become the "normal" ruling pattern of the Soviet Union. He argued that the Party had successfully set up checks and balances to ensure the continuity of the Soviet leadership. Khrushchev's rule was, according to Gilison, proof that the one-man dominance in Soviet politics had ended. As he noted, Khrushchev "was forced to retreat from unceremoniously from previously stated positions". The "grey men" of the party bureaucracy, Gilison believed, were to become the future Soviet leaders. Dennis Ross

, an American diplomat, believed the late Brezhnev-era leadership had evolved into a "rule by committee", pointing to several collective Politburo decisions as evidence. Grey Hodnett, another analyst, believed that "freer communication" and "access to relevant official information" during the Brezhnev Era had contributed to strengthening the Politburo's collective leadership.

According to Thomas A. Baylis, the author of Governing by Committee: Collegial Leadership in Advanced Societies, the existence of collective leadership was due to the individual Politburo members enhancing their own positions by strengthening the collective. Ellen Jones

, an educator, noted how each Politburo member specialised in his own field and acted as that field's spokesman in the Politburo. Therefore, collective leadership was divided into Party and Government institutional and organisational lines. The dominant faction, Jones believed, acted as a "coalition" government of several social forces. This development led some to believe that the Soviet Union had evolved into neo-corporatism. Some believed Soviet factionalism to be "feudal in character". Personal relationship were created to ensure service and support. "Personal factionalism", as Baylis calls it, could either strengthen or weaken the collective leadership's majority.

Robert Osborn wrote in 1974 that collective leadership did not necessarily mean that the Central Committee, Politburo and the Council of Ministers were political equals without a clear leading figure. Baylis believed that the post of General Secretary could be compared to the office of Prime Minister

in the Westminster system

. The General Secretary in the Soviet political system acted as the leading broker in Politburo sessions and could be considered "the Party leader" due to his negotiation skills and successful tactics which retained the Politburo's support. In other words, the General Secretary needed to retain Politburo consensus if he wanted to remain in office.

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

(USSR). Its main task was to distribute powers and functions among the Politburo, the Central Committee

Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

The Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union , abbreviated in Russian as ЦК, "Tse-ka", earlier was also called as the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party ...

, and the Council of Ministers to hinder any attempts to create a one-man dominance

Autocracy

An autocracy is a form of government in which one person is the supreme power within the state. It is derived from the Greek : and , and may be translated as "one who rules by himself". It is distinct from oligarchy and democracy...

over the Soviet political system by a Soviet leader, such as that seen under Joseph Stalin

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin was the Premier of the Soviet Union from 6 May 1941 to 5 March 1953. He was among the Bolshevik revolutionaries who brought about the October Revolution and had held the position of first General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union's Central Committee...

's rule. On the national level, the heart of the collective leadership was officially the Central Committee of the Communist Party

Communist Party of the Soviet Union

The Communist Party of the Soviet Union was the only legal, ruling political party in the Soviet Union and one of the largest communist organizations in the world...

. Collective leadership is characterised by limiting the powers of the General Secretary

General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union was the title given to the leader of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. With some exceptions, the office was synonymous with leader of the Soviet Union...

and the Chairman

Premier of the Soviet Union

The office of Premier of the Soviet Union was synonymous with head of government of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics . Twelve individuals have been premier...

of the Council of Ministers as related to other offices by enhancing the powers of collective bodies, such as the Politburo.

Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Lenin was a Russian Marxist revolutionary and communist politician who led the October Revolution of 1917. As leader of the Bolsheviks, he headed the Soviet state during its initial years , as it fought to establish control of Russia in the Russian Civil War and worked to create a...

was, according to Soviet literature, the perfect example of a leader ruling in favour of the collective. Stalin's rule was characterised by one-man dominance, which was a deep breach of inner-party democracy

Democratic centralism

Democratic centralism is the name given to the principles of internal organization used by Leninist political parties, and the term is sometimes used as a synonym for any Leninist policy inside a political party...

and collective leadership; this made his leadership highly controversial in the Soviet Union following his death in 1953. At the 20th Party Congress, Stalin's reign was criticised as the "cult of the individual". Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev led the Soviet Union during part of the Cold War. He served as First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964, and as Chairman of the Council of Ministers, or Premier, from 1958 to 1964...

, Stalin's successor, supported the ideal of collective leadership but only ruled in a collective fashion when it suited him. In 1964, Khrushchev was ousted due to his disregard of collective leadership and was replaced in his posts by Leonid Brezhnev

Leonid Brezhnev

Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev – 10 November 1982) was the General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union , presiding over the country from 1964 until his death in 1982. His eighteen-year term as General Secretary was second only to that of Joseph Stalin in...

as First Secretary and by Alexei Kosygin as Premier. Collective leadership was strengthened during the Brezhnev years and the later reigns of Yuri Andropov

Yuri Andropov

Yuri Vladimirovich Andropov was a Soviet politician and the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 12 November 1982 until his death fifteen months later.-Early life:...

and Konstantin Chernenko

Konstantin Chernenko

Konstantin Ustinovich Chernenko was a Soviet politician and the fifth General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. He led the Soviet Union from 13 February 1984 until his death thirteen months later, on 10 March 1985...

. Mikhail Gorbachev

Mikhail Gorbachev

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev is a former Soviet statesman, having served as General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1985 until 1991, and as the last head of state of the USSR, having served from 1988 until its dissolution in 1991...

's reforms helped spawn factionalism within the Soviet leadership, and members of Gorbachev's faction openly disagreed with him on key issues. The factions usually disagreed on how little or how much reform was needed to rejuvenate the Soviet system.

Early years

Soviet ideologists believed that Vladimir LeninVladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Lenin was a Russian Marxist revolutionary and communist politician who led the October Revolution of 1917. As leader of the Bolsheviks, he headed the Soviet state during its initial years , as it fought to establish control of Russia in the Russian Civil War and worked to create a...

, the first Soviet leader, thought that only collective leadership could protect the Party from serious mistakes. Joseph Stalin

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin was the Premier of the Soviet Union from 6 May 1941 to 5 March 1953. He was among the Bolshevik revolutionaries who brought about the October Revolution and had held the position of first General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union's Central Committee...

promoted these values; however, instead of creating a new collective leadership, he created an autocratic leadership

Autocracy

An autocracy is a form of government in which one person is the supreme power within the state. It is derived from the Greek : and , and may be translated as "one who rules by himself". It is distinct from oligarchy and democracy...

centered around himself. After Stalin's death, his successors, who were vying for control over the Soviet leadership, promoted the values of collective leadership. Georgy Malenkov

Georgy Malenkov

Georgy Maximilianovich Malenkov was a Soviet politician, Communist Party leader and close collaborator of Joseph Stalin. After Stalin's death, he became Premier of the Soviet Union and was in 1953 briefly considered the most powerful Soviet politician before being overshadowed by Nikita...

, Lavrentiy Beria

Lavrentiy Beria

Lavrentiy Pavlovich Beria was a Georgian Soviet politician and state security administrator, chief of the Soviet security and secret police apparatus under Joseph Stalin during World War II, and Deputy Premier in the postwar years ....

and Vyacheslav Molotov

Vyacheslav Molotov

Vyacheslav Mikhailovich Molotov was a Soviet politician and diplomat, an Old Bolshevik and a leading figure in the Soviet government from the 1920s, when he rose to power as a protégé of Joseph Stalin, to 1957, when he was dismissed from the Presidium of the Central Committee by Nikita Khrushchev...

formed a collective leadership immediately after Stalin's death, but it collapsed when Malenkov and Molotov deceived Beria. After the arrest of Beria, Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev led the Soviet Union during part of the Cold War. He served as First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964, and as Chairman of the Council of Ministers, or Premier, from 1958 to 1964...

proclaimed that collective leadership was the "supreme principle of our Party". He further stated that only decisions approved by the Central Committee

Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

The Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union , abbreviated in Russian as ЦК, "Tse-ka", earlier was also called as the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party ...

(CC) could ensure good leadership for the party and the country. In reality, however, Khrushchev promoted these ideas so that he could win enough support to remove his opponents from power, the most notable of whom was Premier Malenkov in 1955.

Stalin's rule was criticised during the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

Communist Party of the Soviet Union

The Communist Party of the Soviet Union was the only legal, ruling political party in the Soviet Union and one of the largest communist organizations in the world...

as a "cult of the individual". He was accused of reducing the Party's activities and putting an end to Party democracy

Democratic centralism

Democratic centralism is the name given to the principles of internal organization used by Leninist political parties, and the term is sometimes used as a synonym for any Leninist policy inside a political party...

among others. In the three years following Stalin's death, the Central Committee and the Presidium (Politburo) worked consistently to uphold the collective leadership lost under Stalin. Khrushchev's rule as First Secretary remained highly controversial throughout his rule in the Party leadership. The first attempt to depose Khrushchev came in 1957, when the Anti-Party Group

Anti-Party Group

The Anti-Party Group was a group within the leadership of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union that unsuccessfully attempted to depose Nikita Khrushchev as First Secretary of the Party in May 1957. The group, named by that epithet by Khrushchev, was led by former Premiers Georgy Malenkov and...

accused him of individualistic leadership. The coup failed, but Khrushchev's position was drastically weakened. However, Khrushchev continued to call his rule as a rule of the collective even after becoming Chairman

Premier of the Soviet Union

The office of Premier of the Soviet Union was synonymous with head of government of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics . Twelve individuals have been premier...

of the Council of Ministers (Premier of the Soviet Union) by replacing Nikolai Bulganin

Nikolai Bulganin

Nikolai Alexandrovich Bulganin was a prominent Soviet politician, who served as Minister of Defense and Premier of the Soviet Union . The Bulganin beard is named after him.-Early career:...

. At the 22nd Party Congress, Khrushchev declared an end to the dictatorship of the proletariat

Dictatorship of the proletariat

In Marxist socio-political thought, the dictatorship of the proletariat refers to a socialist state in which the proletariat, or the working class, have control of political power. The term, coined by Joseph Weydemeyer, was adopted by the founders of Marxism, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, in the...

and the establishment of the All-People's State. The All-People's State would strengthen collective decision-making within such government institutions as, for instance, the Supreme Soviet. This concept meant that everyone had the opportunity to become active in government leadership politics on a rotational basis, and that one-third of the Soviets'

Soviet (council)

Soviet was a name used for several Russian political organizations. Examples include the Czar's Council of Ministers, which was called the “Soviet of Ministers”; a workers' local council in late Imperial Russia; and the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union....

representatives would be replaced with new members at every election

Elections in the Soviet Union

The electoral system of the Soviet Union was based upon Chapter XI of the Constitution of the Soviet Union and by the Electoral Laws enacted in conformity with it. The Constitution and laws applied to elections in all Soviets, from the Supreme Soviets of the USSR, the Union republics and ...

. Some state administrative functions and powers were to be moved to other public institutions and democratic rule would also be expanded under the All-People's State. However, in 1967 the new Soviet leadership revised the definition, and created a new definition in which All-People's State simply meant an extension of the dictatorship of the proletariat.

Collectivity of leadership

Most Western observers believed that Khrushchev had become the supreme leader of the Soviet Union by the early 1960s, even if this was far from the truth. The Presidium, which had grown to resent Khrushchev's leadership style and feared Mao ZedongMao Zedong

Mao Zedong, also transliterated as Mao Tse-tung , and commonly referred to as Chairman Mao , was a Chinese Communist revolutionary, guerrilla warfare strategist, Marxist political philosopher, and leader of the Chinese Revolution...

's one-man dominance

Autocracy

An autocracy is a form of government in which one person is the supreme power within the state. It is derived from the Greek : and , and may be translated as "one who rules by himself". It is distinct from oligarchy and democracy...

and the growing cult of personality in the People's Republic of China

People's Republic of China

China , officially the People's Republic of China , is the most populous country in the world, with over 1.3 billion citizens. Located in East Asia, the country covers approximately 9.6 million square kilometres...

, began an aggressive campaign against Khrushchev in 1963. This campaign culminated in 1964 with the replacement of Khrushchev in his offices of First Secretary by Leonid Brezhnev

Leonid Brezhnev

Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev – 10 November 1982) was the General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union , presiding over the country from 1964 until his death in 1982. His eighteen-year term as General Secretary was second only to that of Joseph Stalin in...

and of Chairman of the Council of Ministers by Alexei Kosygin. Brezhnev and Kosygin, along with Mikhail Suslov

Mikhail Suslov

Mikhail Andreyevich Suslov was a Soviet statesman during the Cold War. He served as Second Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1965, and as unofficial Chief Ideologue of the Party until his death in 1982. Suslov was responsible for party democracy and the separation of power...

, Andrei Kirilenko

Andrei Kirilenko (politician)

Andrei Pavlovich Kirilenko was a Soviet statesman from the start to the end of the Cold War. In 1906, Kirilenko was born in Alexeyevka, Belgorod Oblast, Russian Empire, to a Russian working class family. He graduated in the 1920s from a local vocational school, and again in the mid-to-late 1930s...

and Anastas Mikoyan

Anastas Mikoyan

Anastas Ivanovich Mikoyan was an Armenian Old Bolshevik and Soviet statesman during the rules of Vladimir Lenin, Joseph Stalin, Nikita Khrushchev, and Leonid Brezhnev....

(replaced in 1965 by Nikolai Podgorny

Nikolai Podgorny

Nikolai Viktorovich Podgorny was a Soviet Ukrainian statesman during the Cold War. He served as First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine, or leader of the Ukrainian SSR, from 1957 to 1963 and as Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet from 1965 to 1977...

), were elected to their respective offices to form and lead a functioning collective leadership. One of the reasons for Khrushchev's ousting, as Suslov told him, was his violation of collective leadership. With Khrushchev's removal, collective leadership was again praised by the Soviet media, and it was claimed to be a return to "Leninist norms of Party life

Leninism

In Marxist philosophy, Leninism is the body of political theory for the democratic organisation of a revolutionary vanguard party, and the achievement of a direct-democracy dictatorship of the proletariat, as political prelude to the establishment of socialism...

". At the plenum which ousted Khrushchev, the Central Committee forbade any single individual to hold the office of General Secretary

General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union was the title given to the leader of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. With some exceptions, the office was synonymous with leader of the Soviet Union...

and Premier simultaneously.

The leadership was usually referred to as the "Brezhnev–Kosygin" leadership, instead of the collective leadership, by First World

First World

The concept of the First World first originated during the Cold War, where it was used to describe countries that were aligned with the United States. These countries were democratic and capitalistic. After the fall of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War, the term "First World" took on a...

medias. At first, there was no clear leader of the collective leadership, and Kosygin was the chief economic administrator, whereas Brezhnev was primarily responsible for the day-to-day management of the party and internal affairs. Kosygin's position was later weakened when he introduced a reform in 1965

1965 Soviet economic reform

The 1965 Soviet economic reform, widely referred to simply as the Kosygin reform or Liberman reform, was a reform of economic management and planning, carried out between 1965 and 1971...

that attempted to decentralise the Soviet economy. The reform led to a backlash, with Kosygin losing supporters because many top officials took an increasingly anti-reformist stance due to the Prague Spring

Prague Spring

The Prague Spring was a period of political liberalization in Czechoslovakia during the era of its domination by the Soviet Union after World War II...

of 1968. As the years passed, Brezhnev was given more and more prominence, and by the 1970s he had even created a "Secretariat of the General Secretary" to strengthen his position within the Party. At the 25th Party Congress, Brezhnev was, according to an anonymous historian, praised in a way that exceeded the praise accorded to Khrushchev before his removal. Brezhnev was able to retain the Politburo's support by not introducing the same sweeping reform measures as seen during Khrushchev's rule. As noted by foreign officials, Brezhnev felt "obliged" to discuss unanticipated proposals with the Politburo before responding to them.

Later years

As Brezhnev's health worsened during the late-1970s, the collective leadership became even more "collective". Brezhnev's deathDeath and funeral of Leonid Brezhnev

On 10 November 1982, Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev, the third General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and the fifth leader of the Soviet Union, died a 75 year-old man after suffering a heart attack following years of serious ailments. His death was officially acknowledged on 11...

did not alter the balance the power

Separation of Power

Separation of Power is Vince Flynn's fourth novel, and the third to feature Mitch Rapp, an American agent that works for the CIA as an operative for a covert counterterrorism unit called the "Orion Team."-Plot summary:...

in any radical fashion, and Yuri Andropov

Yuri Andropov

Yuri Vladimirovich Andropov was a Soviet politician and the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 12 November 1982 until his death fifteen months later.-Early life:...

and Konstantin Chernenko

Konstantin Chernenko

Konstantin Ustinovich Chernenko was a Soviet politician and the fifth General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. He led the Soviet Union from 13 February 1984 until his death thirteen months later, on 10 March 1985...

were obliged by protocol to rule the country in the very same fashion as Brezhnev. When Mikhail Gorbachev was elected to the position of General Secretary in March 1985, some observers wondered if he could be the leader who could overcome the restraints of the collective leadership. Gorbachev's reform agenda had succeeded in altering the Soviet political system

Politics of the Soviet Union

The political system of the Soviet Union was characterized by the superior role of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union , the only party permitted by Constitution.For information about the government, see Government of the Soviet Union-Background:...

for good; however, this change created him more enemies. Many of Gorbachev's closest allies disagreed with him on what reforms were needed, or how radical they were to be. The claim that the Secretariat was the Party's "centre of power" was proven false in 1988 when it was shown that Yegor Ligachev

Yegor Ligachev

Yegor Kuzmich Ligachev is a Russian politician who was a high-ranking official in the Communist Party of the Soviet Union . Originally a protege of Mikhail Gorbachev, Ligachev became a challenger to his leadership.-Early life:...

chaired its meetings, rather than Gorbachev.

Soviet assessments

According to Soviet literature, the Central CommitteeCentral Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

The Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union , abbreviated in Russian as ЦК, "Tse-ka", earlier was also called as the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party ...

and not the Politburo was the heart of collective leadership at the national level. At a sub-national level, all Party and Government organs were to work together to ensure collective leadership instead of only the Central Committee. However, as with many other ideological theses, the definition of collective leadership was applied "flexibly to a variety of situations". Making Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Lenin was a Russian Marxist revolutionary and communist politician who led the October Revolution of 1917. As leader of the Bolsheviks, he headed the Soviet state during its initial years , as it fought to establish control of Russia in the Russian Civil War and worked to create a...

the example of a ruler ruling in favour of a collective can be seen as proof of this "flexibility". In some Soviet ideological drafts, collective leadership can be compared to collegial leadership

Collegiality

Collegiality is the relationship between colleagues.Colleagues are those explicitly united in a common purpose and respecting each other's abilities to work toward that purpose...

instead of a leadership of the collective. In accordance with a Soviet textbook, collective leadership was:

The regular convocations of Party congresses and plenary sessions of the Central Committee, regular meetings of all electoral organs of the party, general public discussion of the major issues of state, economic and party development, extensive consultation with persons employed in various branches of the economy and cultural life...."

In contrast to fascism

Fascism

Fascism is a radical authoritarian nationalist political ideology. Fascists seek to rejuvenate their nation based on commitment to the national community as an organic entity, in which individuals are bound together in national identity by suprapersonal connections of ancestry, culture, and blood...

, which advocates one-man dominance

Autocracy

An autocracy is a form of government in which one person is the supreme power within the state. It is derived from the Greek : and , and may be translated as "one who rules by himself". It is distinct from oligarchy and democracy...

, Leninism

Leninism

In Marxist philosophy, Leninism is the body of political theory for the democratic organisation of a revolutionary vanguard party, and the achievement of a direct-democracy dictatorship of the proletariat, as political prelude to the establishment of socialism...

advocates inner-Party democratic collective leadership. Hence, the ideological justification of collective leadership in the Soviet Union was easy to justify. The physical insecurity of the political leadership under Stalin, and the political insecurity that existed during Khrushchev's reign, strengthened the political leadership's will to ensure a rule of the collective, and not that of the individual. Collective leadership was a value that was highly esteemed during Stalin and Khrushchev's reigns, but it was violated in practice.

Outside observers

Richard Löwenthal

Richard Löwenthal was a Jewish German journalist and professor who wrote mostly on the problems of democracy, communism, and world politics.- Life :...

, a German professor, believed that the Soviet Union had evolved from being a totalitarian state under the rule of Joseph Stalin

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin was the Premier of the Soviet Union from 6 May 1941 to 5 March 1953. He was among the Bolshevik revolutionaries who brought about the October Revolution and had held the position of first General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union's Central Committee...

into a system that he called "post-totalitarian authoritarianism", or "authoritarian bureaucratic oligarchy", in which the Soviet state remained omnipotent in theory and highly authoritarian in practice. However, it did considerably reduce the scale of repression and allowed a much greater level of pluralism into public life. In a 1960 paper, Löwenthal wrote that one-man leadership was "the normal rule of line in a one-party state". The majority of First World

First World

The concept of the First World first originated during the Cold War, where it was used to describe countries that were aligned with the United States. These countries were democratic and capitalistic. After the fall of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War, the term "First World" took on a...

observers tended to agree with Löwenthal on the grounds that a collective leadership in an authoritarian state was "inherently unworkable" in practice, claiming that a collective leadership would sooner or later always give in for one-man rule. In a different interpretation, the Soviet Union was seen to go into periods of "oligarchy" and "limited-personal rule". Oligarchy, in the sense that no individual could "prevent the adoption of policies in which he may be opposed", was seen as an unstable form of government. "Limited-personal rule", in contrast with Joseph Stalin

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin was the Premier of the Soviet Union from 6 May 1941 to 5 March 1953. He was among the Bolshevik revolutionaries who brought about the October Revolution and had held the position of first General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union's Central Committee...

's "personal rule", was a type of governance in which major policy-making decision could not be made without the consent of the leader, while the leader had to tolerate some opposition to his policies and to his leadership in general.

The historian T. H. Rigby claimed that the Soviet leadership was setting up checks and balances within the Party to ensure the stability of collective leadership. One anonymous historian went so far as to claim that collective leadership was bound to triumph in any future Soviet political system. Professor Jerome Gilison argued that collective leadership had become the "normal" ruling pattern of the Soviet Union. He argued that the Party had successfully set up checks and balances to ensure the continuity of the Soviet leadership. Khrushchev's rule was, according to Gilison, proof that the one-man dominance in Soviet politics had ended. As he noted, Khrushchev "was forced to retreat from unceremoniously from previously stated positions". The "grey men" of the party bureaucracy, Gilison believed, were to become the future Soviet leaders. Dennis Ross

Dennis Ross

Dennis B. Ross is an American diplomat and author. He has served as the Director of Policy Planning in the State Department under President George H. W...

, an American diplomat, believed the late Brezhnev-era leadership had evolved into a "rule by committee", pointing to several collective Politburo decisions as evidence. Grey Hodnett, another analyst, believed that "freer communication" and "access to relevant official information" during the Brezhnev Era had contributed to strengthening the Politburo's collective leadership.

According to Thomas A. Baylis, the author of Governing by Committee: Collegial Leadership in Advanced Societies, the existence of collective leadership was due to the individual Politburo members enhancing their own positions by strengthening the collective. Ellen Jones

Mary Ellen Jones

Mary Ellen Jones is an educator and politician most notable for having served as New York State Senator. She is a Democrat.Jones graduated with a bachelor's and master's degree from the University of Rochester. She served as a first-grade teacher in the Greece, New York school district for 26...

, an educator, noted how each Politburo member specialised in his own field and acted as that field's spokesman in the Politburo. Therefore, collective leadership was divided into Party and Government institutional and organisational lines. The dominant faction, Jones believed, acted as a "coalition" government of several social forces. This development led some to believe that the Soviet Union had evolved into neo-corporatism. Some believed Soviet factionalism to be "feudal in character". Personal relationship were created to ensure service and support. "Personal factionalism", as Baylis calls it, could either strengthen or weaken the collective leadership's majority.

Robert Osborn wrote in 1974 that collective leadership did not necessarily mean that the Central Committee, Politburo and the Council of Ministers were political equals without a clear leading figure. Baylis believed that the post of General Secretary could be compared to the office of Prime Minister

Prime minister

A prime minister is the most senior minister of cabinet in the executive branch of government in a parliamentary system. In many systems, the prime minister selects and may dismiss other members of the cabinet, and allocates posts to members within the government. In most systems, the prime...

in the Westminster system

Westminster System

The Westminster system is a democratic parliamentary system of government modelled after the politics of the United Kingdom. This term comes from the Palace of Westminster, the seat of the Parliament of the United Kingdom....

. The General Secretary in the Soviet political system acted as the leading broker in Politburo sessions and could be considered "the Party leader" due to his negotiation skills and successful tactics which retained the Politburo's support. In other words, the General Secretary needed to retain Politburo consensus if he wanted to remain in office.