Charles Piazzi Smyth

Encyclopedia

Charles Piazzi Smyth was Astronomer Royal for Scotland

from 1846 to 1888, well-known for many innovations in astronomy

and his pyramidological

and metrological

studies of the Great Pyramid of Giza

.

, Italy to Captain (later Admiral) William Henry Smyth

and his wife Annarella. He was called Piazzi after his godfather

, the Italian astronomer Giuseppe Piazzi

, whose acquaintance his father had made at Palermo

when serving in the Mediterranean. His father subsequently settled at Bedford

and equipped there an observatory

, at which Piazzi Smyth received his first lessons in astronomy. At the age of sixteen he became an assistant to Sir Thomas Maclear

at the Cape of Good Hope

, where he observed

Halley's comet and the Great Comet of 1843

, and took an active part in the verification and extension of Nicolas Louis de Lacaille

's arc of the meridian.

In 1846 he was appointed Astronomer Royal for Scotland

, based at the Calton Hill Observatory

in

Edinburgh

, and professor of astronomy in the University of Edinburgh

. Shortly after his appointment, the observatory was placed

under the control of Her Majesty's Treasury and suffered from a long series of under-funding. Because of this, most of his notable

work in astronomy was done elsewhere. Here he completed the reduction, and continued the series, of the observations made by his predecessor,

Thomas James Henderson

. In 1853, Smyth was responsible for installing the time ball

on top of Nelson's Monument in Edinburgh to give a time signal to the ships at Edinburgh's port of Leith

. By 1861, this visual signal was augmented by the

One O'Clock Gun at Edinburgh Castle

.

In 1704 Isaac Newton

wrote in his book Opticks

Book 1, Part 1

' ... [telescopes] ... cannot be so formed as to take away that confusion of the Rays which arises from the Tremors of the Atmosphere. The only Remedy is a most serene and quiet Air, such as may perhaps be found on the tops of the highest Mountains above the grosser Clouds.' This suggestion fell on deaf ears until in 1856, Smyth petitioned the Admiralty

for a grant of £500 to take a telescope to the slopes of Teide

in Tenerife

(which he spelt Teneriffe) and test whether Newton had been right or not. In South Africa he had spent many nights observing from mountain tops but when he moved to Edinburgh had been appalled by the poor observing conditions there.

The Admiralty approved his grant and he was offered the loan of further equipment from many sources. Robert Stephenson

loaned his 140 ton yacht 'Titania' for the expedition. Mr. Hugh Pattinson loaned his refracting telescope

of 7 inches (17.8 cm). This was a Thomas Cooke

equatorial with setting circles and a driving clock. The Crimean War

had recently concluded and the army offered to lend tents. This offer was declined as Piazzi Smyth had already designed a tent with a sewn-in groundsheet based on his experience in South Africa.

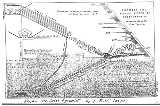

On this and all his subsequent trips he was accompanied by his wife whom he had married the previous year. In 1856, on reaching Tenerife they

first set up camp on Mount Guajara

, a 8900 ft (2,712.7 m) peak about 4 miles (6.4 km) south of Teide (all heights on Tenerife are those he derived barometrically). It was higher than all its neighbours and free from any volcanic activity. They took all their equipment up loaded on mules, except for the Pattinson telescope which was much too bulky. They stayed there a month making astronomical, meteorological and

geological observations. He made observations of the steadiness and clarity of star images with the 3.6-inch (9 cm) Sheepshanks telescope and

found both much better than at Edinburgh. He also made the first positive detection of heat coming from the Moon

. Unfortunately they

were annoyed by frequent dust incursions which frequently blotted out the horizon. Even when the dust was at its worst, the transparency at

the zenith was better than at Edinburgh.

The dust was evidently confined to individual layers, so he decided to move to Alta Vista at 10700 ft (3,261.4 m), on the eastern slope of Teide, the highest point that mules could reach. He was determined to use the larger Pattinson telescope and returned to Orotava to fetch it. As the three

boxes were too heavy, they were opened and the contents distributed

among several smaller boxes which were loaded on to seven strong

horses. The telescope was soon mounted and in action. The Airy Disc

was

clearly seen and he made many critical observations and

fine drawings. They spent a month there during which they spent a day

climbing to the summit of Teide at 12200 ft (3,718.6 m).

The scientific results were described in reports addressed to the

Lord Commissioners of the Admiralty, the Royal Society

, and

the 'Astronomical Observations made at the Royal Observatory,

Edinburgh Vol XII 1863' which were widely acclaimed.

Piazzi Smyth was the pioneer of the modern practice of placing

telescopes at high altitudes to enjoy the best observing conditions.

He wrote a popular account of the voyage in

'Teneriffe, an astronomers Experiment'. This was the first book ever

illustrated by stereoscopic photographs ('photo-stereographs'). It

included 20 stereoviews of Teneriffe

taken by the author using the wet

collodion process

. A stereoscope could be purchased which allowed

the pictures to be viewed in 3-D without removing them from the book.

In 1871 and 1872 Smyth investigated the spectra of the

aurora

, and zodiacal light

. He recommended the use

of the rain-band for weather forecasting

and discovered, in

conjunction with Alexander Stewart Herschel, the harmonic relation

between the rays emitted by carbon monoxide

. In 1877-1878 he

constructed at Lisbon

a map of the solar

spectrum

for

which he received the Makdougall Brisbane

Prize in 1880. Smyth carried out further spectroscopic

researches at Madeira

in 1880 and at Winchester

in 1884.

In 1888 Smyth resigned as Astronomer Royal in protest at the chronic

under-funding and age of his equipment. This brought

events to a head and the Royal Observatory was almost closed when

James Linday, Earl of

Crawford

made a donation of new astronomical instruments and the

complete Bibliotheca Lindesiana in order that a new observatory

could be founded. Thanks to this donation, the new Royal Observatory

on Blackford Hill

was opened in 1896. After his resignation,

Smyth retired to the neighbourhood of Ripon

, where he remained

until his death.

and was heavily influenced by him. Taylor theorized in his 1859 book The Great Pyramid: Why Was It Built? & Who Built It? that the Great Pyramid was planned and the building supervised by the biblical Noah

. Refused a grant by the Royal Society, Smyth went on an expedition to Egypt in order to accurately measure every surface, dimension, and aspect of the Great Pyramid. He brought along equipment to measure the dimensions of the stones, the precise angle of sections such as the descending passage, and a specially designed camera

to photograph both the interior and exterior of the pyramid. He also used other instruments to make astronomical calculations and determine the pyramid's accurate latitude and longitude.

Smyth subsequently published his book Our Inheritance in the Great Pyramid in 1864 (which he expanded over the years and is also titled The Great Pyramid: Its Secrets and Mysteries Revealed). Smyth claimed that the measurements he obtained from the Great Pyramid of Giza indicated a unit of length, the pyramid inch

, equivalent to 1.001 British

inches, that could have been the standard of measurement by the pyramid's architects. From this he extrapolated a number of other measurements, including the pyramid pint

, the sacred cubit

, and the pyramid scale of temperature

.

Smyth claimed, and presumably believed, that the pyramid inch was a God-given measure handed down through the centuries from the time of Shem (Noah's Son), and that the architects of the pyramid could only have been directed by the hand of God. To support this Smyth said that, in measuring the pyramid, he found the number of inches in the perimeter of the base equalled one thousand times the number of days in a year, and found a numeric relationship between the height of the pyramid in inches to the distance from Earth to the Sun, measured in statute miles. He also advanced the theory that the Great Pyramid was a repository of prophecies

which could be revealed by detailed measurements of the structure. Working upon theories by Taylor, he conjectured that the Hyksos

were the Hebrew people

, and that they built the Great Pyramid under the leadership of Melchizedek

. Because the pyramid inch was a divine unit of measurement, Smyth, a committed proponent of British Israelism

, used his conclusions as an argument against the introduction of the metric system

in Britain. For much of his life he was a vocal opponent of the metric system, which he considered a product of the minds of atheistic French

radicals, a position advocated in many of his works.

Smyth, despite his bad reputation in Egyptological circles today, performed much valuable work at Giza. He made the most accurate measurements of the Great Pyramid that any explorer had made up to that time, and he photographed the interior passages, using a magnesium

light, for the first time. Smyth's work resulted in many drawings and calculations, which were soon incorporated into his books Our Inheritance in the Great Pyramid, the three-volume Life and Work at the Great Pyramid (1867), and On the Antiquity of Intellectual Man (1868). For his works he was awarded a gold metal by the Royal Society of Edinburgh, but in 1874, the Royal Society rejected his paper on the design of Khufu's pyramid, as they had Taylor's. The rejection of his ideas helped contribute to his resignation from his post as Royal Astronomer in 1888.

(such as his Studies in the Scriptures

), who founded the Bible Student movement

(most visible today in the Jehovah's Witnesses

, though Russell's successor, Joseph F. Rutherford, denounced pyramidology as unscriptural). Smyth's proposed dates for the Second Coming

, first 1882 then many dates between 1892 and 1911, were failed predictions.

The theories of Taylor and Smyth gained many eminent supporters and detractors in the field of Egyptology during the late 1800s, but by the end of the 19th century it had lost most of its mainstream scientific support. The greatest blow to the theory was dealt by the great Egyptogist William Matthew Flinders Petrie

, who had initially been a supporter. When Petrie went to Egypt in 1880 to perform new measurements, he found that the pyramid was several feet smaller than previously believed. This so undermined the theory that Petrie rejected it, writing "there is no authentic example, that will bear examination, of the use or existence of any such measure as a 'Pyramid inch,' or of a cubit of 25.025 British inches."

. His brothers were Warington Wilkinson Smyth

and Henry Augustus Smyth

. His sisters were Henrietta Grace Smyth, who married Reverend Baden Powell

and was mother of Robert Baden-Powell, 1st Baron Baden-Powell

(founder of the world Scouting Movement), and Georgiana Rosetta Smyth, who married William Henry Flower

.

Smyth died in 1900 and was buried at St. John's Church in the village of Sharow

near Ripon

. A small stone pyramid-shaped monument, topped by a Christian cross

, marks his gravesite http://www.sharow.org.uk/st-johns-church/church-charles-p-smyth.html.

The crater Piazzi Smyth

on the Moon is named after him.

Full text available from Google Books Full text available from Google Books

Astronomer Royal for Scotland

Astronomer Royal for Scotland was the title of the director of the Royal Observatory, Edinburgh until 1995. It has since been an honorary title.The following have served as Astronomers Royal for Scotland:* 1834–1844 Thomas Henderson...

from 1846 to 1888, well-known for many innovations in astronomy

Astronomy

Astronomy is a natural science that deals with the study of celestial objects and phenomena that originate outside the atmosphere of Earth...

and his pyramidological

Pyramidology

Pyramidology is a term used, sometimes disparagingly, to refer to various pseudoscientific speculations regarding pyramids, most often the Giza Necropolis and the Great Pyramid of Giza in Egypt...

and metrological

Pseudoscientific metrology

Some approaches in the branch of historic metrology are highly speculative and can be qualified as pseudoscience. Interest in ancient metrology was triggered by research into the various Megalith building cultures and the Great Pyramid of Giza.-Origins:...

studies of the Great Pyramid of Giza

Great Pyramid of Giza

The Great Pyramid of Giza is the oldest and largest of the three pyramids in the Giza Necropolis bordering what is now El Giza, Egypt. It is the oldest of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, and the only one to remain largely intact...

.

Astronomical career

Charles Piazzi Smyth was born in NaplesNaples

Naples is a city in Southern Italy, situated on the country's west coast by the Gulf of Naples. Lying between two notable volcanic regions, Mount Vesuvius and the Phlegraean Fields, it is the capital of the region of Campania and of the province of Naples...

, Italy to Captain (later Admiral) William Henry Smyth

William Henry Smyth

William Henry Smyth was an English sailor, hydrographer, astronomer and numismatist.-Private Life:...

and his wife Annarella. He was called Piazzi after his godfather

Godparent

A godparent, in many denominations of Christianity, is someone who sponsors a child's baptism. A male godparent is a godfather, and a female godparent is a godmother...

, the Italian astronomer Giuseppe Piazzi

Giuseppe Piazzi

Giuseppe Piazzi was an Italian Catholic priest of the Theatine order, mathematician, and astronomer. He was born in Ponte in Valtellina, and died in Naples. He established an observatory at Palermo, now the Osservatorio Astronomico di Palermo – Giuseppe S...

, whose acquaintance his father had made at Palermo

Palermo

Palermo is a city in Southern Italy, the capital of both the autonomous region of Sicily and the Province of Palermo. The city is noted for its history, culture, architecture and gastronomy, playing an important role throughout much of its existence; it is over 2,700 years old...

when serving in the Mediterranean. His father subsequently settled at Bedford

Bedford

Bedford is the county town of Bedfordshire, in the East of England. It is a large town and the administrative centre for the wider Borough of Bedford. According to the former Bedfordshire County Council's estimates, the town had a population of 79,190 in mid 2005, with 19,720 in the adjacent town...

and equipped there an observatory

Observatory

An observatory is a location used for observing terrestrial or celestial events. Astronomy, climatology/meteorology, geology, oceanography and volcanology are examples of disciplines for which observatories have been constructed...

, at which Piazzi Smyth received his first lessons in astronomy. At the age of sixteen he became an assistant to Sir Thomas Maclear

Thomas Maclear

Sir Thomas Maclear was an Irish-born South African astronomer who became Her Majesty's astronomer at the Cape of Good Hope....

at the Cape of Good Hope

Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope is a rocky headland on the Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula, South Africa.There is a misconception that the Cape of Good Hope is the southern tip of Africa, because it was once believed to be the dividing point between the Atlantic and Indian Oceans. In fact, the...

, where he observed

Halley's comet and the Great Comet of 1843

Great Comet of 1843

The Great Comet of 1843 formally designated C/1843 D1 and 1843 I, was a long-period comet which became very bright in March 1843 . It was discovered on February 5, 1843 and rapidly brightened to become a great comet...

, and took an active part in the verification and extension of Nicolas Louis de Lacaille

Nicolas Louis de Lacaille

Abbé Nicolas Louis de Lacaille was a French astronomer.He is noted for his catalogue of nearly 10,000 southern stars, including 42 nebulous objects. This catalogue, called Coelum Australe Stelliferum, was published posthumously in 1763. It introduced 14 new constellations which have since become...

's arc of the meridian.

In 1846 he was appointed Astronomer Royal for Scotland

Astronomer Royal for Scotland

Astronomer Royal for Scotland was the title of the director of the Royal Observatory, Edinburgh until 1995. It has since been an honorary title.The following have served as Astronomers Royal for Scotland:* 1834–1844 Thomas Henderson...

, based at the Calton Hill Observatory

City Observatory, Edinburgh

The City Observatory is an astronomical observatory on Calton Hill in Edinburgh, Scotland. It is also known as the Calton Hill Observatory....

in

Edinburgh

Edinburgh

Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland, the second largest city in Scotland, and the eighth most populous in the United Kingdom. The City of Edinburgh Council governs one of Scotland's 32 local government council areas. The council area includes urban Edinburgh and a rural area...

, and professor of astronomy in the University of Edinburgh

University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh, founded in 1583, is a public research university located in Edinburgh, the capital of Scotland, and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The university is deeply embedded in the fabric of the city, with many of the buildings in the historic Old Town belonging to the university...

. Shortly after his appointment, the observatory was placed

under the control of Her Majesty's Treasury and suffered from a long series of under-funding. Because of this, most of his notable

work in astronomy was done elsewhere. Here he completed the reduction, and continued the series, of the observations made by his predecessor,

Thomas James Henderson

Thomas James Henderson

Thomas James Alan Henderson was a Scottish astronomer noted for being the first person to measure the distance to Alpha Centauri, the major component of the nearest stellar system to Earth, and for being the first Astronomer Royal for Scotland.-Early life:Born in Dundee, Scotland, he was educated...

. In 1853, Smyth was responsible for installing the time ball

Time ball

A time ball is a large painted wooden or metal ball that drops at a predetermined time, principally to enable sailors to check their marine chronometers from their boats offshore...

on top of Nelson's Monument in Edinburgh to give a time signal to the ships at Edinburgh's port of Leith

Leith

-South Leith v. North Leith:Up until the late 16th century Leith , comprised two separate towns on either side of the river....

. By 1861, this visual signal was augmented by the

One O'Clock Gun at Edinburgh Castle

Edinburgh Castle

Edinburgh Castle is a fortress which dominates the skyline of the city of Edinburgh, Scotland, from its position atop the volcanic Castle Rock. Human habitation of the site is dated back as far as the 9th century BC, although the nature of early settlement is unclear...

.

In 1704 Isaac Newton

Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton PRS was an English physicist, mathematician, astronomer, natural philosopher, alchemist, and theologian, who has been "considered by many to be the greatest and most influential scientist who ever lived."...

wrote in his book Opticks

Opticks

Opticks is a book written by English physicist Isaac Newton that was released to the public in 1704. It is about optics and the refraction of light, and is considered one of the great works of science in history...

Book 1, Part 1

' ... [telescopes] ... cannot be so formed as to take away that confusion of the Rays which arises from the Tremors of the Atmosphere. The only Remedy is a most serene and quiet Air, such as may perhaps be found on the tops of the highest Mountains above the grosser Clouds.' This suggestion fell on deaf ears until in 1856, Smyth petitioned the Admiralty

Admiralty

The Admiralty was formerly the authority in the Kingdom of England, and later in the United Kingdom, responsible for the command of the Royal Navy...

for a grant of £500 to take a telescope to the slopes of Teide

Teide

Mount Teide , is a volcano on Tenerife, Canary Islands. Its summit is the highest point in Spain, the highest point above sea level in the islands of the Atlantic, and it is the third highest volcano in the world measured from its base on the ocean floor, after Mauna Loa and Mauna Kea located in...

in Tenerife

Tenerife

Tenerife is the largest and most populous island of the seven Canary Islands, it is also the most populated island of Spain, with a land area of 2,034.38 km² and 906,854 inhabitants, 43% of the total population of the Canary Islands. About five million tourists visit Tenerife each year, the...

(which he spelt Teneriffe) and test whether Newton had been right or not. In South Africa he had spent many nights observing from mountain tops but when he moved to Edinburgh had been appalled by the poor observing conditions there.

The Admiralty approved his grant and he was offered the loan of further equipment from many sources. Robert Stephenson

Robert Stephenson

Robert Stephenson FRS was an English civil engineer. He was the only son of George Stephenson, the famed locomotive builder and railway engineer; many of the achievements popularly credited to his father were actually the joint efforts of father and son.-Early life :He was born on the 16th of...

loaned his 140 ton yacht 'Titania' for the expedition. Mr. Hugh Pattinson loaned his refracting telescope

Refracting telescope

A refracting or refractor telescope is a type of optical telescope that uses a lens as its objective to form an image . The refracting telescope design was originally used in spy glasses and astronomical telescopes but is also used for long focus camera lenses...

of 7 inches (17.8 cm). This was a Thomas Cooke

Thomas Cooke

This page is about the instrument maker. For other persons named Thomas Cooke, see Thomas CookeThomas Cooke was a British instrument maker based on York. He founded T. Cooke & Sons, the instrument company-Life:...

equatorial with setting circles and a driving clock. The Crimean War

Crimean War

The Crimean War was a conflict fought between the Russian Empire and an alliance of the French Empire, the British Empire, the Ottoman Empire, and the Kingdom of Sardinia. The war was part of a long-running contest between the major European powers for influence over territories of the declining...

had recently concluded and the army offered to lend tents. This offer was declined as Piazzi Smyth had already designed a tent with a sewn-in groundsheet based on his experience in South Africa.

On this and all his subsequent trips he was accompanied by his wife whom he had married the previous year. In 1856, on reaching Tenerife they

first set up camp on Mount Guajara

Mount Guajara

Mount Guajara is a 2718 m high mountain on Tenerife, in the Canary Islands....

, a 8900 ft (2,712.7 m) peak about 4 miles (6.4 km) south of Teide (all heights on Tenerife are those he derived barometrically). It was higher than all its neighbours and free from any volcanic activity. They took all their equipment up loaded on mules, except for the Pattinson telescope which was much too bulky. They stayed there a month making astronomical, meteorological and

geological observations. He made observations of the steadiness and clarity of star images with the 3.6-inch (9 cm) Sheepshanks telescope and

found both much better than at Edinburgh. He also made the first positive detection of heat coming from the Moon

Moon

The Moon is Earth's only known natural satellite,There are a number of near-Earth asteroids including 3753 Cruithne that are co-orbital with Earth: their orbits bring them close to Earth for periods of time but then alter in the long term . These are quasi-satellites and not true moons. For more...

. Unfortunately they

were annoyed by frequent dust incursions which frequently blotted out the horizon. Even when the dust was at its worst, the transparency at

the zenith was better than at Edinburgh.

The dust was evidently confined to individual layers, so he decided to move to Alta Vista at 10700 ft (3,261.4 m), on the eastern slope of Teide, the highest point that mules could reach. He was determined to use the larger Pattinson telescope and returned to Orotava to fetch it. As the three

boxes were too heavy, they were opened and the contents distributed

among several smaller boxes which were loaded on to seven strong

horses. The telescope was soon mounted and in action. The Airy Disc

Airy disc

In optics, the Airy disk and Airy pattern are descriptions of the best focused spot of light that a perfect lens with a circular aperture can make, limited by the diffraction of light....

was

clearly seen and he made many critical observations and

fine drawings. They spent a month there during which they spent a day

climbing to the summit of Teide at 12200 ft (3,718.6 m).

The scientific results were described in reports addressed to the

Lord Commissioners of the Admiralty, the Royal Society

Royal Society

The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, known simply as the Royal Society, is a learned society for science, and is possibly the oldest such society in existence. Founded in November 1660, it was granted a Royal Charter by King Charles II as the "Royal Society of London"...

, and

the 'Astronomical Observations made at the Royal Observatory,

Edinburgh Vol XII 1863' which were widely acclaimed.

Piazzi Smyth was the pioneer of the modern practice of placing

telescopes at high altitudes to enjoy the best observing conditions.

He wrote a popular account of the voyage in

'Teneriffe, an astronomers Experiment'. This was the first book ever

illustrated by stereoscopic photographs ('photo-stereographs'). It

included 20 stereoviews of Teneriffe

taken by the author using the wet

collodion process

Collodion process

The collodion process is an early photographic process. It was introduced in the 1850s and by the end of that decade it had almost entirely replaced the first practical photographic process, the daguerreotype. During the 1880s the collodion process, in turn, was largely replaced by gelatin dry...

. A stereoscope could be purchased which allowed

the pictures to be viewed in 3-D without removing them from the book.

In 1871 and 1872 Smyth investigated the spectra of the

aurora

Aurora (astronomy)

An aurora is a natural light display in the sky particularly in the high latitude regions, caused by the collision of energetic charged particles with atoms in the high altitude atmosphere...

, and zodiacal light

Zodiacal light

Zodiacal light is a faint, roughly triangular, whitish glow seen in the night sky which appears to extend up from the vicinity of the sun along the ecliptic or zodiac. Caused by sunlight scattered by space dust in the zodiacal cloud, it is so faint that either moonlight or light pollution renders...

. He recommended the use

of the rain-band for weather forecasting

Weather forecasting

Weather forecasting is the application of science and technology to predict the state of the atmosphere for a given location. Human beings have attempted to predict the weather informally for millennia, and formally since the nineteenth century...

and discovered, in

conjunction with Alexander Stewart Herschel, the harmonic relation

between the rays emitted by carbon monoxide

Carbon monoxide

Carbon monoxide , also called carbonous oxide, is a colorless, odorless, and tasteless gas that is slightly lighter than air. It is highly toxic to humans and animals in higher quantities, although it is also produced in normal animal metabolism in low quantities, and is thought to have some normal...

. In 1877-1878 he

constructed at Lisbon

Lisbon

Lisbon is the capital city and largest city of Portugal with a population of 545,245 within its administrative limits on a land area of . The urban area of Lisbon extends beyond the administrative city limits with a population of 3 million on an area of , making it the 9th most populous urban...

a map of the solar

Sun

The Sun is the star at the center of the Solar System. It is almost perfectly spherical and consists of hot plasma interwoven with magnetic fields...

spectrum

Spectrum

A spectrum is a condition that is not limited to a specific set of values but can vary infinitely within a continuum. The word saw its first scientific use within the field of optics to describe the rainbow of colors in visible light when separated using a prism; it has since been applied by...

for

which he received the Makdougall Brisbane

Prize in 1880. Smyth carried out further spectroscopic

researches at Madeira

Madeira

Madeira is a Portuguese archipelago that lies between and , just under 400 km north of Tenerife, Canary Islands, in the north Atlantic Ocean and an outermost region of the European Union...

in 1880 and at Winchester

Winchester

Winchester is a historic cathedral city and former capital city of England. It is the county town of Hampshire, in South East England. The city lies at the heart of the wider City of Winchester, a local government district, and is located at the western end of the South Downs, along the course of...

in 1884.

In 1888 Smyth resigned as Astronomer Royal in protest at the chronic

under-funding and age of his equipment. This brought

events to a head and the Royal Observatory was almost closed when

James Linday, Earl of

Crawford

James Lindsay, 26th Earl of Crawford

James Ludovic Lindsay, 26th Earl of Crawford and 9th Earl of Balcarres was a British astronomer, politician, bibliophile and philatelist. A member of the Royal Society, Crawford was elected president of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1878. He was a prominent Freemason.-Family:The Earl was the...

made a donation of new astronomical instruments and the

complete Bibliotheca Lindesiana in order that a new observatory

could be founded. Thanks to this donation, the new Royal Observatory

Royal Observatory, Edinburgh

The Royal Observatory, Edinburgh is an astronomical institution located on Blackford Hill in Edinburgh, Scotland. The site is owned by the Science and Technology Facilities Council...

on Blackford Hill

Blackford, Edinburgh

Blackford is an area in the south of Edinburgh, Scotland. It is a reasonably affluent area, and contains Blackford Hill, one of the supposed "Seven Hills of Edinburgh", which has the city's Astronomical observatory on it...

was opened in 1896. After his resignation,

Smyth retired to the neighbourhood of Ripon

Ripon

Ripon is a cathedral city, market town and successor parish in the Borough of Harrogate, North Yorkshire, England, located at the confluence of two streams of the River Ure in the form of the Laver and Skell. The city is noted for its main feature the Ripon Cathedral which is architecturally...

, where he remained

until his death.

Pyramidological researches

Smyth corresponded with pyramid theorist John TaylorJohn Taylor (1781-1864)

John Taylor was a publisher, essayist, and writer born in East Retford, Nottinghamshire, the son of James Taylor and Sarah Drury. Although in pyramidical circles, he may be remembered for his contributions to Pyramidology and his use of that subject in the fight against adopting the metric system...

and was heavily influenced by him. Taylor theorized in his 1859 book The Great Pyramid: Why Was It Built? & Who Built It? that the Great Pyramid was planned and the building supervised by the biblical Noah

Noah

Noah was, according to the Hebrew Bible, the tenth and last of the antediluvian Patriarchs. The biblical story of Noah is contained in chapters 6–9 of the book of Genesis, where he saves his family and representatives of all animals from the flood by constructing an ark...

. Refused a grant by the Royal Society, Smyth went on an expedition to Egypt in order to accurately measure every surface, dimension, and aspect of the Great Pyramid. He brought along equipment to measure the dimensions of the stones, the precise angle of sections such as the descending passage, and a specially designed camera

Camera

A camera is a device that records and stores images. These images may be still photographs or moving images such as videos or movies. The term camera comes from the camera obscura , an early mechanism for projecting images...

to photograph both the interior and exterior of the pyramid. He also used other instruments to make astronomical calculations and determine the pyramid's accurate latitude and longitude.

Smyth subsequently published his book Our Inheritance in the Great Pyramid in 1864 (which he expanded over the years and is also titled The Great Pyramid: Its Secrets and Mysteries Revealed). Smyth claimed that the measurements he obtained from the Great Pyramid of Giza indicated a unit of length, the pyramid inch

Pyramid inch

The pyramid inch is a unit of measure claimed by pyramidologists to have been used in ancient times. Supposedly it was one twenty-fifth of a "sacred cubit", 1.00106 imperial inches, or 2.5426924 centimetres.-History:...

, equivalent to 1.001 British

English unit

English units are the historical units of measurement used in England up to 1824, which evolved as a combination of the Anglo-Saxon and Roman systems of units...

inches, that could have been the standard of measurement by the pyramid's architects. From this he extrapolated a number of other measurements, including the pyramid pint

Pint

The pint is a unit of volume or capacity that was once used across much of Europe with values varying from state to state from less than half a litre to over one litre. Within continental Europe, the pint was replaced with the metric system during the nineteenth century...

, the sacred cubit

Cubit

The cubit is a traditional unit of length, based on the length of the forearm. Cubits of various lengths were employed in many parts of the world in Antiquity, in the Middle Ages and into Early Modern Times....

, and the pyramid scale of temperature

Temperature measurement

Attempts of standardized temperature measurement have been reported as early as 170 AD by Claudius Galenus. The modern scientific field has its origins in the works by Florentine scientists in the 17th century. Early devices to measure temperature were called thermoscopes. The first sealed...

.

Smyth claimed, and presumably believed, that the pyramid inch was a God-given measure handed down through the centuries from the time of Shem (Noah's Son), and that the architects of the pyramid could only have been directed by the hand of God. To support this Smyth said that, in measuring the pyramid, he found the number of inches in the perimeter of the base equalled one thousand times the number of days in a year, and found a numeric relationship between the height of the pyramid in inches to the distance from Earth to the Sun, measured in statute miles. He also advanced the theory that the Great Pyramid was a repository of prophecies

Prophecy

Prophecy is a process in which one or more messages that have been communicated to a prophet are then communicated to others. Such messages typically involve divine inspiration, interpretation, or revelation of conditioned events to come as well as testimonies or repeated revelations that the...

which could be revealed by detailed measurements of the structure. Working upon theories by Taylor, he conjectured that the Hyksos

Hyksos

The Hyksos were an Asiatic people who took over the eastern Nile Delta during the twelfth dynasty, initiating the Second Intermediate Period of ancient Egypt....

were the Hebrew people

Hebrews

Hebrews is an ethnonym used in the Hebrew Bible...

, and that they built the Great Pyramid under the leadership of Melchizedek

Melchizedek

Melchizedek or Malki Tzedek translated as "my king righteous") is a king and priest mentioned during the Abram narrative in the 14th chapter of the Book of Genesis....

. Because the pyramid inch was a divine unit of measurement, Smyth, a committed proponent of British Israelism

British Israelism

British Israelism is the belief that people of Western European descent, particularly those in Great Britain, are the direct lineal descendants of the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel. The concept often includes the belief that the British Royal Family is directly descended from the line of King David...

, used his conclusions as an argument against the introduction of the metric system

Metric system

The metric system is an international decimalised system of measurement. France was first to adopt a metric system, in 1799, and a metric system is now the official system of measurement, used in almost every country in the world...

in Britain. For much of his life he was a vocal opponent of the metric system, which he considered a product of the minds of atheistic French

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

radicals, a position advocated in many of his works.

Smyth, despite his bad reputation in Egyptological circles today, performed much valuable work at Giza. He made the most accurate measurements of the Great Pyramid that any explorer had made up to that time, and he photographed the interior passages, using a magnesium

Magnesium

Magnesium is a chemical element with the symbol Mg, atomic number 12, and common oxidation number +2. It is an alkaline earth metal and the eighth most abundant element in the Earth's crust and ninth in the known universe as a whole...

light, for the first time. Smyth's work resulted in many drawings and calculations, which were soon incorporated into his books Our Inheritance in the Great Pyramid, the three-volume Life and Work at the Great Pyramid (1867), and On the Antiquity of Intellectual Man (1868). For his works he was awarded a gold metal by the Royal Society of Edinburgh, but in 1874, the Royal Society rejected his paper on the design of Khufu's pyramid, as they had Taylor's. The rejection of his ideas helped contribute to his resignation from his post as Royal Astronomer in 1888.

Influence of Smyth's pyramid theories

Smyth's theories on pyramid prophecy were then integrated into the works and prophecies of Charles Taze RussellCharles Taze Russell

Charles Taze Russell , or Pastor Russell, was a prominent early 20th century Christian restorationist minister from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA, and founder of what is now known as the Bible Student movement, from which Jehovah's Witnesses and numerous independent Bible Student groups emerged...

(such as his Studies in the Scriptures

Studies in the Scriptures

Studies in the Scriptures is a series of publications, intended as a Bible study aid, containing seven volumes of great importance to the history of the Bible Students, and the early history of the Jehovah's Witnesses.-Origin and author:...

), who founded the Bible Student movement

Bible Student movement

The Bible Student movement is the name adopted by a Millennialist Restorationist Christian movement that emerged from the teachings and ministry of Charles Taze Russell, also known as Pastor Russell...

(most visible today in the Jehovah's Witnesses

Jehovah's Witnesses

Jehovah's Witnesses is a millenarian restorationist Christian denomination with nontrinitarian beliefs distinct from mainstream Christianity. The religion reports worldwide membership of over 7 million adherents involved in evangelism, convention attendance of over 12 million, and annual...

, though Russell's successor, Joseph F. Rutherford, denounced pyramidology as unscriptural). Smyth's proposed dates for the Second Coming

Second Coming

In Christian doctrine, the Second Coming of Christ, the Second Advent, or the Parousia, is the anticipated return of Jesus Christ from Heaven, where he sits at the Right Hand of God, to Earth. This prophecy is found in the canonical gospels and in most Christian and Islamic eschatologies...

, first 1882 then many dates between 1892 and 1911, were failed predictions.

The theories of Taylor and Smyth gained many eminent supporters and detractors in the field of Egyptology during the late 1800s, but by the end of the 19th century it had lost most of its mainstream scientific support. The greatest blow to the theory was dealt by the great Egyptogist William Matthew Flinders Petrie

William Matthew Flinders Petrie

William Matthew Flinders Petrie FRS , commonly known as Flinders Petrie, was an English Egyptologist and a pioneer of systematic methodology in archaeology and preservation of artifacts...

, who had initially been a supporter. When Petrie went to Egypt in 1880 to perform new measurements, he found that the pyramid was several feet smaller than previously believed. This so undermined the theory that Petrie rejected it, writing "there is no authentic example, that will bear examination, of the use or existence of any such measure as a 'Pyramid inch,' or of a cubit of 25.025 British inches."

Marriage, family, and death

In 1856 Smyth married Jessie Duncan (died 1896), daughter of Thomas DuncanThomas Duncan

Thomas Duncan, RA was a Scottish portrait and historical painter born in Kinclaven, Perthshire.Educated at the Perth Academy, he began studying law, but abandoned it for art...

. His brothers were Warington Wilkinson Smyth

Warington Wilkinson Smyth

Sir Warington Wilkinson Smyth was a British geologist.-Biography:Smyth was born at Naples, the son of Admiral W. H. Smyth and his wife Annarella Warington. His father was engaged in the Admiralty Survey of the Mediterranean at the time of his birth. Smyth was educated at Westminster and...

and Henry Augustus Smyth

Henry Augustus Smyth

Sir Henry Augustus Smyth , FSA, FRGS, Governor of Malta, general and colonel commandant Royal Artillery, born at St James's Street, London, on 25 November 1825, was third son in the family of three sons and six daughters of Admiral William Henry Smyth by his wife Annarella, only daughter of Thomas...

. His sisters were Henrietta Grace Smyth, who married Reverend Baden Powell

Baden Powell (mathematician)

Baden Powell, MA, FRS, FRGS was an English mathematician and Church of England priest. He was also prominent as a liberal theologian who put forward advanced ideas about evolution. He held the Savilian Chair of Geometry at the University of Oxford from 1827 to 1860...

and was mother of Robert Baden-Powell, 1st Baron Baden-Powell

Robert Baden-Powell, 1st Baron Baden-Powell

Robert Stephenson Smyth Baden-Powell, 1st Baron Baden-Powell, Bt, OM, GCMG, GCVO, KCB , also known as B-P or Lord Baden-Powell, was a lieutenant-general in the British Army, writer, and founder of the Scout Movement....

(founder of the world Scouting Movement), and Georgiana Rosetta Smyth, who married William Henry Flower

William Henry Flower

Sir William Henry Flower KCB FRCS FRS was an English comparative anatomist and surgeon. Flower became a leading authority on mammals, and especially on the primate brain...

.

Smyth died in 1900 and was buried at St. John's Church in the village of Sharow

Sharow

Sharow is a village and civil parish in the Harrogate district of North Yorkshire, England. It is about north-east of Ripon.Sharow currently has three Saturday cricket teams that play in the Nidderdale Amateur Cricket League...

near Ripon

Ripon

Ripon is a cathedral city, market town and successor parish in the Borough of Harrogate, North Yorkshire, England, located at the confluence of two streams of the River Ure in the form of the Laver and Skell. The city is noted for its main feature the Ripon Cathedral which is architecturally...

. A small stone pyramid-shaped monument, topped by a Christian cross

Christian cross

The Christian cross, seen as a representation of the instrument of the crucifixion of Jesus Christ, is the best-known religious symbol of Christianity...

, marks his gravesite http://www.sharow.org.uk/st-johns-church/church-charles-p-smyth.html.

Honours

In June 1857 he was elected a fellow of the Royal SocietyThe crater Piazzi Smyth

Piazzi Smyth (crater)

Piazzi Smyth is a small lunar impact crater in the eastern part of the Mare Imbrium. This is an isolated feature located about 100 kilometers to the southwest of the Montes Alpes mountain range...

on the Moon is named after him.

Selected works and sources by Smyth

Full text available from Google Books Reprinted in many editions by many publishers, often entitled The Great Pyramid: Its Secrets and Mysteries Revealed. Full text available on the Internet ArchiveInternet Archive

The Internet Archive is a non-profit digital library with the stated mission of "universal access to all knowledge". It offers permanent storage and access to collections of digitized materials, including websites, music, moving images, and nearly 3 million public domain books. The Internet Archive...

Full text available from Google Books Full text available from Google Books

Useful Biographical Information

- Critical comments on some of Smyth's books, by Olin J. Eggen (1955).

External links

- see, for instance here- "Charles Piazzi Smythe" at History of Astronomy in South Africa

- Pyramidology - A Case of Science, Pseudo-science and Religion

- Charles Piazzi Smyth, Our Inheritance in the Great Pyramid (1877) Plate Index

- C. Piazzi Smyth, Charles Taze Russell and the Great Pyramid of Gizeh

- Amazing Pyramid "Facts"

- B-P's Uncle: Charles Piazzi Smyth

- "Charles Piazzi Smith" at the Gazetteer for Scotland

- St. John's Church, Sharow: Charles Piazzi Smyth

- The Astronomical Society of Edinburgh: A Guide to Edinburgh's Popular Observatory

- Doomsday 1701-1970

- "Charles Piazzi Smyth - Teneriffe" at the George Eastman House Still Photograph Archive

- "The Sphinx and the Great Pyramid at Giza, 1865" photograph by Smyth

- The Royal Observatory, Edinburgh

- Astronomers Royal For Scotland: Summary of Archives

See also

- Astronomer Royal for ScotlandAstronomer Royal for ScotlandAstronomer Royal for Scotland was the title of the director of the Royal Observatory, Edinburgh until 1995. It has since been an honorary title.The following have served as Astronomers Royal for Scotland:* 1834–1844 Thomas Henderson...

- Royal Observatory, EdinburghRoyal Observatory, EdinburghThe Royal Observatory, Edinburgh is an astronomical institution located on Blackford Hill in Edinburgh, Scotland. The site is owned by the Science and Technology Facilities Council...

- PyramidologyPyramidologyPyramidology is a term used, sometimes disparagingly, to refer to various pseudoscientific speculations regarding pyramids, most often the Giza Necropolis and the Great Pyramid of Giza in Egypt...

- Pyramid inchPyramid inchThe pyramid inch is a unit of measure claimed by pyramidologists to have been used in ancient times. Supposedly it was one twenty-fifth of a "sacred cubit", 1.00106 imperial inches, or 2.5426924 centimetres.-History:...

- Pseudoscientific metrologyPseudoscientific metrologySome approaches in the branch of historic metrology are highly speculative and can be qualified as pseudoscience. Interest in ancient metrology was triggered by research into the various Megalith building cultures and the Great Pyramid of Giza.-Origins:...

- Great Pyramid of GizaGreat Pyramid of GizaThe Great Pyramid of Giza is the oldest and largest of the three pyramids in the Giza Necropolis bordering what is now El Giza, Egypt. It is the oldest of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, and the only one to remain largely intact...

- John TaylorJohn Taylor (1781-1864)John Taylor was a publisher, essayist, and writer born in East Retford, Nottinghamshire, the son of James Taylor and Sarah Drury. Although in pyramidical circles, he may be remembered for his contributions to Pyramidology and his use of that subject in the fight against adopting the metric system...