Anton Ivanovich Denikin

Encyclopedia

Anton Ivanovich Denikin (Анто́н Ива́нович Дени́кин; August 8, 1947) was Lieutenant General

of the Imperial Russian Army

(1916) and one of the foremost generals of the White movement

in the Russian Civil War

.

). His father, Ivan Efimovich Denikin, had been born a serf

in the province of Saratov

. Sent as a recruit to do 25 years of military service, Ivan Denikin became an officer on the 22nd year of his army service, in 1856. He retired from the army in 1869 with the rank of a major. In 1869 Ivan Denikin married a poor Polish seamstress, Elżbieta Wrzesińska - his second wife. Anton Denikin, the couple's only child, learned to speak two languages (Russian and Polish) at the same time. His father's commitment to Russian patriotism and the Orthodox religion

was crucial for Anton Denikin's decision to become a soldier.

The Denikins lived very close to poverty, the retired major's small pension being their only source of income. After his father's death in 1885, Denikin's family financial situation got even worse. Anton Denikin began tutoring younger schoolmates so that the family could earn an additional income. In 1890 Denikin began a course at the Kiev Junker School, a military college from which he graduated in 1892. Twenty-year-old Denikin joined an artillery brigade, in which he served for three years.

In 1895 he was first accepted into General Staff Academy

, where he did not meet the academic requirements in the first of two years. After the disappointment, Denikin attempted to attain acceptance again. On his next attempt he did better and ended up fourteenth in his class. However, to his misfortune, the Academy decided to introduce a new system of calculating grades and as a result Denikin was not offered a staff appointment after the final exams. Denikin protested the decision to the highest authority (The Grand Duke), and after being offered a settlement which he would rescind his complaint in order to attain acceptance into General Staff school again, Denikin declined, feeling insulted at the lack of integrity presented by the offer.

Denikin first saw active service during the 1905 Russo-Japanese War

. In 1905 he was promoted to the rank of colonel. In 1910 he was appointed commander of the 17th infantry regiment. A few weeks before the outbreak of the First World War

, Denikin reached the rank of major-general.

of General Brusilov

's 8th Army. Not one for staff service, Denikin petitioned for an appointment to a fighting front. He was transferred to the 4th Rifle Brigade. His brigade was transformed into a division in 1915. It was with this brigade Denikin would accomplish his greatest feats as a General.

In 1916 he was appointed to command the Russian VIII Corps and lead troops in Romania

during the last successful Russian campaign of the war, the Brusilov Offensive

. Following the February Revolution

and the overthrow of Tsar

Nicholas II, he became Chief of Staff to Mikhail Alekseev

, then Aleksei Brusilov

, and finally Lavr Kornilov

. Denikin supported the attempted coup of his commander, the Kornilov Affair

, in September 1917 and was arrested and imprisoned with him. After this Alekseev would be reappointed commander-in-Chief.

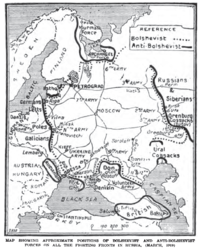

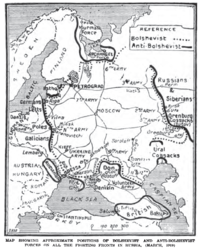

both Denikin and Kornilov escaped to Novocherkassk

in southern Russia and, with other Tsarist officers, formed the anti-Bolshevik

Volunteer Army

, initially commanded by Alekseev. Kornilov was killed in April 1918 near Ekaterinodar and the Volunteer Army came under Denikin's command. There was some sentiment to place Grand Duke Nicholas in overall command, but Denikin was not interested in sharing power. In the face of a Communist counter-offensive he withdrew his forces back towards the Don area in what was known as the Ice March

. Denikin led one final assault of the southern White forces in their final push to capture Moscow

in the summer of 1919. For a time, it appeared that the White Army would succeed in its drive; Leon Trotsky

, as commander of Red Army

forces hastily concluded an agreement with Nestor Makhno

's anarchist Revolutionary Insurrectionary Army of Ukraine

or 'Black Army' for mutual support. Makhno duly turned his Black Army east and led his troops against Denikin's extended lines of supply, forcing him to retreat. Denikin's army was decisively defeated at Orel

in October 1919, some 400 km south of Moscow. The White forces in southern Russia would be in constant retreat thereafter, eventually reaching the Crimea

in March 1920. The Soviet government immediately tore up its agreement with Makhno and attacked his anarchist forces. After a seesaw series of battles in which one side or the other gained a victory, Trotsky's Red Army troops, more numerous and better equipped, defeated and dispersed Makhno's Black Army.

In the occupied territories, Denikin's regime carried out mass executions and plunder, in what was later known as the White Terror

. In the town of Maikop in southern Russia during September 1918, more than 4000 people were massacred by General Pokvrovsky's forces. Denikin's Counterintelligence was characterized by rampant arbitrariness. Prisons were crowded with detains and Volunteer Army soldiers plundered the occupied towns.

Denikin's regime on 24 November 1919 passed a law that determined the internal policy after the expected White victory in the Civil War. Under this law, all those who were involved in activities of the Soviets, who carried out or facilitated its tasks, as well as those who participated "in the Communist Party, which established the power of the Soviets of Workers deputies, is subject to deprivation of all property rights and the death penalty. The death penalty was threatened on all members of the Communist Party numbering more than 300 thousand as well as workers who participated in the nationalization of factories, or contributed to it, or were members of trade unions, peasants who participated in the land reforms, and soldiers of the Red Army.

Denikin's regime on 24 November 1919 passed a law that determined the internal policy after the expected White victory in the Civil War. Under this law, all those who were involved in activities of the Soviets, who carried out or facilitated its tasks, as well as those who participated "in the Communist Party, which established the power of the Soviets of Workers deputies, is subject to deprivation of all property rights and the death penalty. The death penalty was threatened on all members of the Communist Party numbering more than 300 thousand as well as workers who participated in the nationalization of factories, or contributed to it, or were members of trade unions, peasants who participated in the land reforms, and soldiers of the Red Army.

During the Russian Civil War

, an estimated 100,000 Jews perished in pogroms perpetrated by Symon Petlyura's Ukrainian nationalist separatists and the White forces led by Anton Denikin. The press of the Denikin regime regularly incited violence against Jews. For example, a proclamation by one of Denikin's generals incited people to "arm themselves" in order to extirpate "the evil force which lives in the hearts of Jew-communists." In the small town of Fastov alone, Denikin's Volunteer Army murdered over 1500 Jews, mostly elderly, women, and children. An estimated 100,000 Jews were killed in pogroms perpetrated by Denikin's forces and other anti-soviet armies.

Facing increasingly sharp criticism and emotionally exhausted, Denikin resigned in April, 1920 in favor of General Baron Pyotr Wrangel

. Denikin left the Crimea

by ship to Constantinople

and then to London

. He spent a few months in England, then moved to Belgium

, and later to Hungary

.

in 1930 and later General Evgenii K. Miller

in 1937. White Against Red – The Life of General Anton Denikin gives possibly the definitive account of the intrigues during these early Soviet "wet-ops".

Denikin was a talented writer, and before World War I had written several pieces in which he analytically criticized the shortcomings of his beloved Russian Army. His voluminous writings after the Russian Civil War (written while living in exile) are remarkable for their analytical tone and candor. Since he enjoyed writing and most of his income was derived from it, Denikin started to consider himself a writer and developed close friendships with several Russian émigré authors—among them Ivan Bunin (a Nobel Laureate), Ivan Shmelev, and Aleksandr Kuprin

.

Although respected by most of the community of Russian exiles, Denikin was disliked by émigrés of both political extremes, the right and the left.

With the fall of France in 1940, Denikin left Paris in order to avoid imprisonment by the Germans. Although he was eventually captured, he declined all attempts to co-opt him for use in Nazi anti-Soviet propaganda. The Germans did not press the matter and Denikin was allowed to remain in rural exile. Although not formally part of the resistance, his activities would certainly have been sufficient to cause his arrest had they been fully known to the Nazi authorities. Diary entries kept by his wife during this period also make it clear that he was appalled by Nazi anti-Semitism, a fact that may shed light on his actual attitude toward the pogroms of the Russian Civil War. Exactly how "appalled" was Denikin with the endemic anti-Semitism? Historians are well aware that diaries are often written with a view to later publication. In fact, important personages often write several diaries with this in mind. Thus while a diary may not be very reliable, personal observations say much. With this in mind, consider the following:

At the conclusion of the war, correctly anticipating their likely fate at the hands of Joseph Stalin

's Soviet Union

, Denikin attempted to persuade the Western Allies

not to forcibly repatriate Soviet POWs (see also Operation Keelhaul

). He was largely unsuccessful in his effort.

From 1945 until his death in 1947, Denikin lived in the United States, in New York City

. On August 8, 1947, at the age of 74, Denikin died of a heart attack while vacationing near Ann Arbor, Michigan

.

General Denikin was buried with military honors in Detroit. His remains were later transferred to St. Vladimir's Cemetery in Jackson, New Jersey. His wife, Xenia Vasilievna Chizh, was buried at Saint Genevieve de Bois cemetery

near Paris.

On October 3, 2005, in accordance with the wishes of his daughter Marina Denikina

and by authority of President Vladimir Putin

of Russia, General Denikin's remains were transferred from the United States and buried at the Donskoy Monastery

in Moscow.

Lieutenant General

Lieutenant General is a military rank used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages where the title of Lieutenant General was held by the second in command on the battlefield, who was normally subordinate to a Captain General....

of the Imperial Russian Army

Imperial Russian Army

The Imperial Russian Army was the land armed force of the Russian Empire, active from around 1721 to the Russian Revolution of 1917. In the early 1850s, the Russian army consisted of around 938,731 regular soldiers and 245,850 irregulars . Until the time of military reform of Dmitry Milyutin in...

(1916) and one of the foremost generals of the White movement

White movement

The White movement and its military arm the White Army - known as the White Guard or the Whites - was a loose confederation of Anti-Communist forces.The movement comprised one of the politico-military Russian forces who fought...

in the Russian Civil War

Russian Civil War

The Russian Civil War was a multi-party war that occurred within the former Russian Empire after the Russian provisional government collapsed to the Soviets, under the domination of the Bolshevik party. Soviet forces first assumed power in Petrograd The Russian Civil War (1917–1923) was a...

.

Childhood

Denikin was born in Szpetal Dolny village, now a part of the Polish city Włocławek (then part of the Russian EmpireRussian Empire

The Russian Empire was a state that existed from 1721 until the Russian Revolution of 1917. It was the successor to the Tsardom of Russia and the predecessor of the Soviet Union...

). His father, Ivan Efimovich Denikin, had been born a serf

SERF

A spin exchange relaxation-free magnetometer is a type of magnetometer developed at Princeton University in the early 2000s. SERF magnetometers measure magnetic fields by using lasers to detect the interaction between alkali metal atoms in a vapor and the magnetic field.The name for the technique...

in the province of Saratov

Saratov

-Modern Saratov:The Saratov region is highly industrialized, due in part to the rich in natural and industrial resources of the area. The region is also one of the more important and largest cultural and scientific centres in Russia...

. Sent as a recruit to do 25 years of military service, Ivan Denikin became an officer on the 22nd year of his army service, in 1856. He retired from the army in 1869 with the rank of a major. In 1869 Ivan Denikin married a poor Polish seamstress, Elżbieta Wrzesińska - his second wife. Anton Denikin, the couple's only child, learned to speak two languages (Russian and Polish) at the same time. His father's commitment to Russian patriotism and the Orthodox religion

Russian Orthodox Church

The Russian Orthodox Church or, alternatively, the Moscow Patriarchate The ROC is often said to be the largest of the Eastern Orthodox churches in the world; including all the autocephalous churches under its umbrella, its adherents number over 150 million worldwide—about half of the 300 million...

was crucial for Anton Denikin's decision to become a soldier.

The Denikins lived very close to poverty, the retired major's small pension being their only source of income. After his father's death in 1885, Denikin's family financial situation got even worse. Anton Denikin began tutoring younger schoolmates so that the family could earn an additional income. In 1890 Denikin began a course at the Kiev Junker School, a military college from which he graduated in 1892. Twenty-year-old Denikin joined an artillery brigade, in which he served for three years.

In 1895 he was first accepted into General Staff Academy

General Staff Academy (Imperial Russia)

The General Staff Academy was a Russian military academy, established in 1832 in St.Petersburg. It was first known as the Imperial Military Academy , then in 1855 it was renamed Nicholas General Staff Academy and in 1909 - Imperial Nicholas Military Academy The General Staff Academy was a...

, where he did not meet the academic requirements in the first of two years. After the disappointment, Denikin attempted to attain acceptance again. On his next attempt he did better and ended up fourteenth in his class. However, to his misfortune, the Academy decided to introduce a new system of calculating grades and as a result Denikin was not offered a staff appointment after the final exams. Denikin protested the decision to the highest authority (The Grand Duke), and after being offered a settlement which he would rescind his complaint in order to attain acceptance into General Staff school again, Denikin declined, feeling insulted at the lack of integrity presented by the offer.

Denikin first saw active service during the 1905 Russo-Japanese War

Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War was "the first great war of the 20th century." It grew out of rival imperial ambitions of the Russian Empire and Japanese Empire over Manchuria and Korea...

. In 1905 he was promoted to the rank of colonel. In 1910 he was appointed commander of the 17th infantry regiment. A few weeks before the outbreak of the First World War

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

, Denikin reached the rank of major-general.

World War I

By the outbreak of World War I in August 1914 Denikin was a Chief of staff of the Kiev Military District. He was initially appointed QuartermasterQuartermaster

Quartermaster refers to two different military occupations depending on if the assigned unit is land based or naval.In land armies, especially US units, it is a term referring to either an individual soldier or a unit who specializes in distributing supplies and provisions to troops. The senior...

of General Brusilov

Aleksei Brusilov

Aleksei Alekseevich Brusilov was a Russian general most noted for the development of new offensive tactics used in the 1916 offensive which would come to bear his name. The innovative and relatively successful tactics used were later copied by the Germans...

's 8th Army. Not one for staff service, Denikin petitioned for an appointment to a fighting front. He was transferred to the 4th Rifle Brigade. His brigade was transformed into a division in 1915. It was with this brigade Denikin would accomplish his greatest feats as a General.

In 1916 he was appointed to command the Russian VIII Corps and lead troops in Romania

Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central and Southeastern Europe, on the Lower Danube, within and outside the Carpathian arch, bordering on the Black Sea...

during the last successful Russian campaign of the war, the Brusilov Offensive

Brusilov Offensive

The Brusilov Offensive , also known as the June Advance, was the Russian Empire's greatest feat of arms during World War I, and among the most lethal battles in world history. Prof. Graydon A. Tunstall of the University of South Florida called the Brusilov Offensive of 1916 the worst crisis of...

. Following the February Revolution

February Revolution

The February Revolution of 1917 was the first of two revolutions in Russia in 1917. Centered around the then capital Petrograd in March . Its immediate result was the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II, the end of the Romanov dynasty, and the end of the Russian Empire...

and the overthrow of Tsar

Tsar

Tsar is a title used to designate certain European Slavic monarchs or supreme rulers. As a system of government in the Tsardom of Russia and Russian Empire, it is known as Tsarist autocracy, or Tsarism...

Nicholas II, he became Chief of Staff to Mikhail Alekseev

Mikhail Alekseev

Mikhail Vasiliyevich Alekseyev was an Imperial Russian Army general during World War I and the Russian Civil War. Between 1915 and 1917 he was Chief of Staff to Tsar Nicholas II, and after the February Revolution, March–July 1917 the commander in chief of the Russian army...

, then Aleksei Brusilov

Aleksei Brusilov

Aleksei Alekseevich Brusilov was a Russian general most noted for the development of new offensive tactics used in the 1916 offensive which would come to bear his name. The innovative and relatively successful tactics used were later copied by the Germans...

, and finally Lavr Kornilov

Lavr Kornilov

Lavr Georgiyevich Kornilov was a military intelligence officer, explorer, and general in the Imperial Russian Army during World War I and the ensuing Russian Civil War...

. Denikin supported the attempted coup of his commander, the Kornilov Affair

Kornilov Affair

The Kornilov Affair, or the Kornilov Putsch as it is sometimes referred to, was an attempted coup d'état by the then Commander-in-Chief of the Russian Army, General Lavr Kornilov, in August 1917 against the Russian Provisional Government headed by Alexander Kerensky.-Background:Following the...

, in September 1917 and was arrested and imprisoned with him. After this Alekseev would be reappointed commander-in-Chief.

Civil War

Following the October RevolutionOctober Revolution

The October Revolution , also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution , Red October, the October Uprising or the Bolshevik Revolution, was a political revolution and a part of the Russian Revolution of 1917...

both Denikin and Kornilov escaped to Novocherkassk

Novocherkassk

Novocherkassk is a city in Rostov Oblast, Russia, located on the right bank of the Tuzlov River and on the Aksay River. Population: 169,039 ; 170,822 ; 178,000 ; 123,000 ; 81,000 ; 52,000 ....

in southern Russia and, with other Tsarist officers, formed the anti-Bolshevik

Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks, originally also Bolshevists , derived from bol'shinstvo, "majority") were a faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party which split apart from the Menshevik faction at the Second Party Congress in 1903....

Volunteer Army

Volunteer Army

The Volunteer Army was an anti-Bolshevik army in South Russia during the Russian Civil War of 1918-1920....

, initially commanded by Alekseev. Kornilov was killed in April 1918 near Ekaterinodar and the Volunteer Army came under Denikin's command. There was some sentiment to place Grand Duke Nicholas in overall command, but Denikin was not interested in sharing power. In the face of a Communist counter-offensive he withdrew his forces back towards the Don area in what was known as the Ice March

Ice March

The Ice March , also called the First Kuban Campaign , a military withdrawal lasting from February to May 1918, was one of the defining moments in the Russian Civil War of 1917 to 1921...

. Denikin led one final assault of the southern White forces in their final push to capture Moscow

Moscow

Moscow is the capital, the most populous city, and the most populous federal subject of Russia. The city is a major political, economic, cultural, scientific, religious, financial, educational, and transportation centre of Russia and the continent...

in the summer of 1919. For a time, it appeared that the White Army would succeed in its drive; Leon Trotsky

Leon Trotsky

Leon Trotsky , born Lev Davidovich Bronshtein, was a Russian Marxist revolutionary and theorist, Soviet politician, and the founder and first leader of the Red Army....

, as commander of Red Army

Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army started out as the Soviet Union's revolutionary communist combat groups during the Russian Civil War of 1918-1922. It grew into the national army of the Soviet Union. By the 1930s the Red Army was among the largest armies in history.The "Red Army" name refers to...

forces hastily concluded an agreement with Nestor Makhno

Nestor Makhno

Nestor Ivanovych Makhno or simply Daddy Makhno was a Ukrainian anarcho-communist guerrilla leader turned army commander who led an independent anarchist army in Ukraine during the Russian Civil War....

's anarchist Revolutionary Insurrectionary Army of Ukraine

Revolutionary Insurrectionary Army of Ukraine

The Revolutionary Insurrectionary Army of Ukraine , popularly called Makhnovshchina, less correctly Makhnovchina, and also known as the Black Army, was an anarchist army formed largely of Ukrainian and Crimean peasants and workers under the command of the famous anarchist Nestor Makhno during the...

or 'Black Army' for mutual support. Makhno duly turned his Black Army east and led his troops against Denikin's extended lines of supply, forcing him to retreat. Denikin's army was decisively defeated at Orel

Oryol

Oryol or Orel is a city and the administrative center of Oryol Oblast, Russia, located on the Oka River, approximately south-southwest of Moscow...

in October 1919, some 400 km south of Moscow. The White forces in southern Russia would be in constant retreat thereafter, eventually reaching the Crimea

Crimea

Crimea , or the Autonomous Republic of Crimea , is a sub-national unit, an autonomous republic, of Ukraine. It is located on the northern coast of the Black Sea, occupying a peninsula of the same name...

in March 1920. The Soviet government immediately tore up its agreement with Makhno and attacked his anarchist forces. After a seesaw series of battles in which one side or the other gained a victory, Trotsky's Red Army troops, more numerous and better equipped, defeated and dispersed Makhno's Black Army.

In the occupied territories, Denikin's regime carried out mass executions and plunder, in what was later known as the White Terror

White Terror

White Terror is the violence carried out by reactionary groups as part of a counter-revolution. In particular, during the 20th century, in several countries the term White Terror was applied to acts of violence against real or suspected socialists and communists.-Historical origin: the French...

. In the town of Maikop in southern Russia during September 1918, more than 4000 people were massacred by General Pokvrovsky's forces. Denikin's Counterintelligence was characterized by rampant arbitrariness. Prisons were crowded with detains and Volunteer Army soldiers plundered the occupied towns.

During the Russian Civil War

Russian Civil War

The Russian Civil War was a multi-party war that occurred within the former Russian Empire after the Russian provisional government collapsed to the Soviets, under the domination of the Bolshevik party. Soviet forces first assumed power in Petrograd The Russian Civil War (1917–1923) was a...

, an estimated 100,000 Jews perished in pogroms perpetrated by Symon Petlyura's Ukrainian nationalist separatists and the White forces led by Anton Denikin. The press of the Denikin regime regularly incited violence against Jews. For example, a proclamation by one of Denikin's generals incited people to "arm themselves" in order to extirpate "the evil force which lives in the hearts of Jew-communists." In the small town of Fastov alone, Denikin's Volunteer Army murdered over 1500 Jews, mostly elderly, women, and children. An estimated 100,000 Jews were killed in pogroms perpetrated by Denikin's forces and other anti-soviet armies.

Facing increasingly sharp criticism and emotionally exhausted, Denikin resigned in April, 1920 in favor of General Baron Pyotr Wrangel

Pyotr Nikolayevich Wrangel

Baron Pyotr Nikolayevich Wrangel or Vrangel was an officer in the Imperial Russian army and later commanding general of the anti-Bolshevik White Army in Southern Russia in the later stages of the Russian Civil War.-Life:Wrangel was born in Mukuliai, Kovno Governorate in the Russian Empire...

. Denikin left the Crimea

Crimea

Crimea , or the Autonomous Republic of Crimea , is a sub-national unit, an autonomous republic, of Ukraine. It is located on the northern coast of the Black Sea, occupying a peninsula of the same name...

by ship to Constantinople

Istanbul

Istanbul , historically known as Byzantium and Constantinople , is the largest city of Turkey. Istanbul metropolitan province had 13.26 million people living in it as of December, 2010, which is 18% of Turkey's population and the 3rd largest metropolitan area in Europe after London and...

and then to London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

. He spent a few months in England, then moved to Belgium

Belgium

Belgium , officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a federal state in Western Europe. It is a founding member of the European Union and hosts the EU's headquarters, and those of several other major international organisations such as NATO.Belgium is also a member of, or affiliated to, many...

, and later to Hungary

Hungary

Hungary , officially the Republic of Hungary , is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is situated in the Carpathian Basin and is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine and Romania to the east, Serbia and Croatia to the south, Slovenia to the southwest and Austria to the west. The...

.

Exile

From 1926 Denikin lived in France. Although he continued to remain bitterly opposed to Russia's Communist government, he chose to remain discreetly on the periphery of exile politics, spending most of his time writing and lecturing. This did not prevent the Soviets from unsuccessfully targeting him for abduction in the same effort that snared exile General Alexander P. KutepovAlexander Kutepov

Alexander Pavlovich Kutepov was a leader of the anti-communist Volunteer Army during the Russian Civil War....

in 1930 and later General Evgenii K. Miller

Evgenii Miller

Evgeny Karlovich Miller was a Russian general and one of the leaders of the anti-communist White Army during and after Russian Civil War.-Biography:...

in 1937. White Against Red – The Life of General Anton Denikin gives possibly the definitive account of the intrigues during these early Soviet "wet-ops".

Denikin was a talented writer, and before World War I had written several pieces in which he analytically criticized the shortcomings of his beloved Russian Army. His voluminous writings after the Russian Civil War (written while living in exile) are remarkable for their analytical tone and candor. Since he enjoyed writing and most of his income was derived from it, Denikin started to consider himself a writer and developed close friendships with several Russian émigré authors—among them Ivan Bunin (a Nobel Laureate), Ivan Shmelev, and Aleksandr Kuprin

Aleksandr Kuprin

Aleksandr Ivanovich Kuprin , was a Russian writer, pilot, explorer and adventurer who is perhaps best known for his story The Duel . Other well-known works include Moloch , Olesya , Junior Captain Rybnikov , Emerald , and The Garnet Bracelet...

.

Although respected by most of the community of Russian exiles, Denikin was disliked by émigrés of both political extremes, the right and the left.

With the fall of France in 1940, Denikin left Paris in order to avoid imprisonment by the Germans. Although he was eventually captured, he declined all attempts to co-opt him for use in Nazi anti-Soviet propaganda. The Germans did not press the matter and Denikin was allowed to remain in rural exile. Although not formally part of the resistance, his activities would certainly have been sufficient to cause his arrest had they been fully known to the Nazi authorities. Diary entries kept by his wife during this period also make it clear that he was appalled by Nazi anti-Semitism, a fact that may shed light on his actual attitude toward the pogroms of the Russian Civil War. Exactly how "appalled" was Denikin with the endemic anti-Semitism? Historians are well aware that diaries are often written with a view to later publication. In fact, important personages often write several diaries with this in mind. Thus while a diary may not be very reliable, personal observations say much. With this in mind, consider the following:

"I had not been with Denikin more than a month before I was forced to the conclusion that the Jew represented a very big element in the Russian upheaval. The officers and men of the Army laid practically all the blame for their country's troubles on the Hebrew. They held that the whole cataclysm had been engineered by some great and mysterious secret society of international Jews, who, in the pay and at the orders of Germany, had seized the psychological moment and snatched the reins of government. All the figures and facts that were then available appeared to lend colour to this contention. No less than 82 per cent of the Bolshevik Commissars were known to be Jews, the fierce and implacable 'Trotsky,' who shared office with Lenin, being a Yiddisher whose real name was Bronstein. Among Denikin's officers this idea was an obsession of such terrible bitterness and insistency as to lead them into making statements of the wildest and most fantastic character. Many of them had persuaded themselves that Freemasonry was, in alliance with the Jews, part and parcel of the Bolshevik machine, and that what they had called the diabolical schemes for Russia's downfall had been hatched in the Petrograd and Moscow Masonic lodges. When I told them that I and most of my best friends were Freemasons, and that England owed a great deal to its loyal Jews, they stared at me askance and sadly shook their heads in fear for England's credulity in trusting the chosen race. One even asked me quietly whether I personally was a Jew. When America showed herself decidedly against any kind of interference in Russia, the idea soon gained wide credence that President Woodrow Wilson was a Jew, while Mr Lloyd George was referred to as a Jew whenever a cable from England appeared to show him as being lukewarm in support of the anti-Bolsheviks."

At the conclusion of the war, correctly anticipating their likely fate at the hands of Joseph Stalin

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin was the Premier of the Soviet Union from 6 May 1941 to 5 March 1953. He was among the Bolshevik revolutionaries who brought about the October Revolution and had held the position of first General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union's Central Committee...

's Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

, Denikin attempted to persuade the Western Allies

Allies of World War II

The Allies of World War II were the countries that opposed the Axis powers during the Second World War . Former Axis states contributing to the Allied victory are not considered Allied states...

not to forcibly repatriate Soviet POWs (see also Operation Keelhaul

Operation Keelhaul

Operation Keelhaul was carried out in Northern Italy by British and American forces to repatriate Soviet Armed Forces POWs of the Nazis to the Soviet Union between August 14, 1946 and May 9, 1947...

). He was largely unsuccessful in his effort.

From 1945 until his death in 1947, Denikin lived in the United States, in New York City

New York City

New York is the most populous city in the United States and the center of the New York Metropolitan Area, one of the most populous metropolitan areas in the world. New York exerts a significant impact upon global commerce, finance, media, art, fashion, research, technology, education, and...

. On August 8, 1947, at the age of 74, Denikin died of a heart attack while vacationing near Ann Arbor, Michigan

Michigan

Michigan is a U.S. state located in the Great Lakes Region of the United States of America. The name Michigan is the French form of the Ojibwa word mishigamaa, meaning "large water" or "large lake"....

.

General Denikin was buried with military honors in Detroit. His remains were later transferred to St. Vladimir's Cemetery in Jackson, New Jersey. His wife, Xenia Vasilievna Chizh, was buried at Saint Genevieve de Bois cemetery

Sainte-Geneviève-des-Bois Russian Cemetery

Sainte-Geneviève-des-Bois Cemetery, specifically the one known as Cimetière de Liers, as there are two cemeteries in the city, is a Russian Orthodox cemetery, located on Rue Léo Lagrange in Sainte-Geneviève-des-Bois, département Essonne, France....

near Paris.

On October 3, 2005, in accordance with the wishes of his daughter Marina Denikina

Marina Denikina

Marina Antonovna Denikina was a Russian-born French writer and journalist. She was the daughter of Russian general Anton Denikin, leader of the counter-revolutionary White movement in the civil war....

and by authority of President Vladimir Putin

Vladimir Putin

Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin served as the second President of the Russian Federation and is the current Prime Minister of Russia, as well as chairman of United Russia and Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the Union of Russia and Belarus. He became acting President on 31 December 1999, when...

of Russia, General Denikin's remains were transferred from the United States and buried at the Donskoy Monastery

Donskoy Monastery

Donskoy Monastery is a major monastery in Moscow, founded in 1591 in commemoration of Moscow's deliverance from an imminent threat of Khan Kazy-Girey’s invasion...

in Moscow.

Honors

- Golden Sword of St. GeorgeGold Sword for BraveryThe Gold Sword for Bravery was a Russian Empire award for bravery. It was set up with two grades on 27 July 1720 by Peter the Great, reclassified as a public order in 1807 and abolished in 1917. From 1913 to 1917 it was renamed the St George Sword and considered as one of the grades of the Order...

, decorated with diamonds, with the inscription "For the double release of Lutsk (22 September 1916) - Golden Sword of St. GeorgeGold Sword for BraveryThe Gold Sword for Bravery was a Russian Empire award for bravery. It was set up with two grades on 27 July 1720 by Peter the Great, reclassified as a public order in 1807 and abolished in 1917. From 1913 to 1917 it was renamed the St George Sword and considered as one of the grades of the Order...

(10 November 1915) - Order of St. GeorgeOrder of St. GeorgeThe Military Order of the Holy Great-Martyr and the Triumphant George The Military Order of the Holy Great-Martyr and the Triumphant George The Military Order of the Holy Great-Martyr and the Triumphant George (also known as Order of St. George the Triumphant, Russian: Военный орден Св...

, 3rd degree (3 November 1915); 4th degree (24 April 1915) - Order of St Vladimir, 3rd degree (18 April 1914); 4th degree (6 December 1909)

- Order of St. Anne

Order of St. AnnaThe Order of St. Anna ) is a Holstein and then Russian Imperial order of chivalry established by Karl Friedrich, Duke of Holstein-Gottorp on 14 February 1735, in honour of his wife Anna Petrovna, daughter of Peter the Great of Russia...

Order of St. AnnaThe Order of St. Anna ) is a Holstein and then Russian Imperial order of chivalry established by Karl Friedrich, Duke of Holstein-Gottorp on 14 February 1735, in honour of his wife Anna Petrovna, daughter of Peter the Great of Russia...

, 2nd degree with Swords (1905); 3rd degree with swords and bows (1904) - Order of St. Stanislaus, 2nd degree with Swords (1904); 3rd degree (1902)

- Honorary Knight Commander of the Order of Bath, 1919 (UK)

- Order of Michael the BraveOrder of Michael the BraveThe Order of Michael the Brave is Romania's highest military decoration, instituted by King Ferdinand I during the early stages of the Romanian Campaign of World War I, and was again awarded in World War II...

, 3rd degree, 1917 (Romania) - Croix de Guerre, 1914-1918, 1917 (France)

See also

- German Ost (East)

- Symon Petliura

Denikin's works

Denikin wrote several books, including:- Russian Turmoil. Memoirs: Military, Social & Political. Hutchinson. London. 1922.

- Republished: Hyperion Press. 1973. ISBN 9780883551004

- The White Army. Translated by Catherine Zvegintsov. Jonathan Cape, 1930.

- Republished: Hyperion Press. 1973. ISBN 9780883551011.

- Republished: Ian Faulkner Publishing. Cambridge. 1992. ISBN 9781857630107.

- The Career of a Tsarist Officer: Memoirs, 1872-1916. Translated by Margaret Patoski. University of Minnesota Press. 1975.

External links

- Anton Ivanovich Denikin. Biographies at Answers.com. Answers Corporation, 2006.

- Pogroms in Southern Russia; Massacres of Jews in Several Towns Follow Retreat of Denikin's Army; New York Times (February 26, 1920)

- Berkman, Alexander; "FASTOV THE POGROMED" from The Bolshevik Myth, New York: Boni and Liveright, 1925