Zygmunt Wojciechowski

Encyclopedia

Zygmunt Wojciechowski (27 April 1900 – 14 October 1955) was a Polish historian

and nationalist politician, active in the Second Polish Republic

. During the Occupation of Poland

by Nazi Germany

he was a member of the Polish underground. Wojciechowski was the co-initiator of the Polish "Western thought" (myśl zachodnia), and headed the Western Institute

in Poznań

.

(Stryi

, Ukraine

), then Austro-Hungarian

Galicia. In World War I

he volunteered Piłsudski’s Legion

but was not deployed anymore.

In 1921, Wojciechowski began studying at the Jan Kazimierz University

in Lwów, which had then just been re-incorporated in the re-created Polish state (now Lviv

in Ukraine

). In 1924, he obtained a doctorate in medieval history, social sciences, and economics, and became assistant professor at the Institute for Auxiliary Sciences of History

. In 1924 he published his first concept of the "motherland territories" of Poland. His definition of "Polish motherland" defined them as the areas forming 10th-century Piast Poland in the era of Mieszko I and Boleslaw Krzywousty:Masovia, Lesser Poland

, Greater Poland

, Silesia

, Gdańsk Pomerania

, Western Pomerania, Neumark

, West Prussia

). In 1925, he moved to Poznań, where he first was the deputy holder of the chair for the history of the political system and Ancient Polish law at Adam Mickiewicz University (UAM). The same year, he completed his habilitation

with a thesis on the territorial administration of medieval settlements. He became extraordinary (non-tenured) professor in 1929, and full professor in January 1937. From 1939, he was the dean

of the university's Department of Law and Economics.

(leader of endecja

), had been one of the main ideologists of the Camp of Great Poland (OWP). He was active in the right-wing All-Polish Youth and the Liga Narodowa. In 1934 he founded the "League of Young Nationalists" (Związek Młodych Narodowców), whose aim was the foundation of an authoritarian, homogenous Polish state, and became its chairman until 1937. From 1937 to 1939 he was the chairman of the "Nation State Movement" (Ruch Narodowo-Panstwowy) In 1937 he called for a strong national state that would be democratic During his political career he opposed Dmowski and the movement he belonged to sought integration with Józef Piłsudski's sanacja

faction, hoping that both main political factions in Poland would unite led by interest in well being of Polish nation However, he considered Dmowski one of the most influential persons of his life.

Wojciechowski initially saw "traces of a modern national thought" in the National Socialism. He initially admired Hitler's anti-Jewish policy as a good example for Poland. He accepted the Anschluss

of Austria and the Munich Agreement

but became more critical of Hitler's politics in the course of time. According to Tomasz Kenar he was alarmed by Hitler's expansionism but accepted the "Anschluss" of Austria, hoping that it would put Italy against Nazi Germany and into the sphere of Polish alliance. Regarding Munich Agreement he saw Czechoslovakia as too closely allied Soviet Union; while Czechs were in his view natural allies of Poles, their close contacts with the Soviets made such alliance impossible. He remained opposed to German annexation of Czechoslovakia, worried that such event would make Polish military situation difficult. Wojciechowski envisioned a Polish-led block in Central Europe composed of Hungary, Romania, Finland, Estonia,Latvia and Lithuania and in close relationship with Italy, that would oppose both German expansionism and Soviet pressure on these states; he wrote that such alliance would "rescue Christianity" from the threat of "Bolshevik communism" and "hitlerite paganism". Later on he focused his attention towards Fascist Italy

, due to his interest in a "strong state", "depending on legal norms, in tradition of Roman law". While nation was for Wojciechowski at time the "greatest good" he didn't exhibit racist ideas or anything that would be similar to German "volkisch" elements in his works. During Nazi German occupation of Poland he along with his family sheltered a Jewish woman and in a 1945 publication he condemned the mass murder of Jews by Nazi Germany

during the war as "monstrous"

Wojciechowski is described as a co-initiator of the Polish "Western thought" (myśl zachodnia), a "mirror image of the German Ostforschung

with a pinch of pan-Slavic sentiment thrown in". Unlike Ostforschung this movement was marginal in Poland, and limited only to Poznań University, while the Ostforschung was influential and remained (unlike the Poznań thinkers who were in conflict with state authorities both before and after World War II) in friendly relations with Berlin government.

The Polish researchers rejected the state model found in Germany, and preferred Francoist Spain or Salazar's Portugal, remaining distrustful of Hitler. They rejected such ideas as biological racism, eugenics and militarism and neo-pagan movement.

along with other Polish intellectuals, craftsmen, politicians and students. The group was held as part of German effort to crush Polish resistance, and they were threatened with murder in case of armed resistance. Every few days, Wojciechowski was allowed to visit home. If he wouldn't return, the others would be shot. Eventually he was released two months later, due to his pregnant wife's plea. Despite his release, the family faced further reprisals, as it had to flee Poznań

as initial ethnic cleansing

of Poles from the region was initiated by Nazi German authorities. Wojciechowski eventually found refugee at a friend's house in Kraków.

, he was involved with the Polish underground authorities, teaching at the Uniwersytet Ziem Zachodnich ("University of the Western Territories", a part of the necessary underground education system

) necessary, as all Poles were forbidden basic schooling as part of German genocide

regarding Polish nation. He continued his research, and supervised his students (Zdzisław Kaczmarczyk, Kazimierz Kolańczyk) who finished two dissertations. In 1944 He also headed the Government Delegation for Poland's Science Section in the Department of Information, and briefly, after the fall of the Warsaw Uprising

, he was the deputy director of the Department. As part of conspiracy during Nazi German occupation he was one of the founding members of Ojczyzna-Omega, a conspiracy movement that gathered surviving (as Germans carried out systematic extermination of Polish educated classes) Polish intellectuals, priests, journalists, lawyers and teachers, who organised charity work, secret education and worked on concepts of post-war Poland; most of the members were Christian democrats and national democrats

. Ojczyzna-Omega envisioned a post-war Poland that would be a democratic, efficiently administrated state populated mainly by Polish majority alongside Jewish population and Slavic groups. The organisation believed that Nazi Germany(which attempted a genocide of Poles) was far more dangerous than Soviet Union and pushed for a compromise with Soviets.

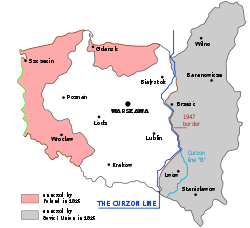

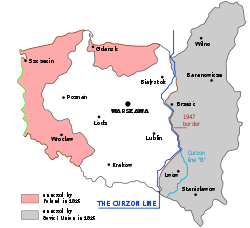

Commissioned by the Union of Armed Struggle, a forerunner of the Home Army, Wojciechowski created a concept of a post-war Polish–German border in 1941, which included an overview of the Polish and Polonizable part of the population in areas between the pre-war border and the Oder-Neisse line

. In tune with and probably in charge of Wojciechowski the director of the library of Kórnik

at that time prepared the takeover of archives, museums and libraries in the future Western territories. In his designs Wojciechowski wanted to avoid what he defined as the mistakes of the Versailles Treaty. The border at Oder and Lusatian Neisse was essential for him, as he considered it, the historical argument was not decisive here, the safest and most defensible one.

On 17 December 1944 Tomasz Arciszewski

, the Polish Prime Minister of the Polish government-in-exile in London, declared in a Sunday Times interview, that a post-war Poland had no territorial claims towards Stettin (Szczecin) and Breslau (Wrocław) but considers Lviv

and Wilna an integral part of the Polish state. This led to a vote of no confidence of the Ojczyzna-group against Arciszewski for this "renunciation of the Polish war aims" and finally to the breakup with the Polish government-in-exile in London. Also in December 1944 he resumed the consequences of the failed Warsaw Uprising

that, fom his view, had shown, that not the Home Army but only the Red Army

was capable to liberate Warsaw.

On 13 February 1945 Wojciechowski met the Prime Minister of the Provisional Government of the Republic of Poland, Edward Osóbka-Morawski

, and handed over a memorandum about the foundation and activities of the Western Institute in which he asked for the support of the institute. The memorandum was addressed to the “Polish government”, thus recognizing the Provisional Government, contrary to the London exile-government, as legitimate.

Conversely Wojciechowski's concept aided the governmental demand to legitimize the Polish acquirements in the West

In 1945 his book "Poland-Germany. Ten centuries of struggle" (first edidion 1933) was reissued. To Wojciechowski the history of Polish-German relations was coined by an eternal struggle against German aggression which was founded on a lack of the ability of Germans to cohabit peacefully with Slavs and their "biological" hatred of everything Slavic. Wojciechowski described his view of the post-war situation:

In 1945 his book "Poland-Germany. Ten centuries of struggle" (first edidion 1933) was reissued. To Wojciechowski the history of Polish-German relations was coined by an eternal struggle against German aggression which was founded on a lack of the ability of Germans to cohabit peacefully with Slavs and their "biological" hatred of everything Slavic. Wojciechowski described his view of the post-war situation:

to Poland.

He resumed teaching at UAM. He became a member of the Polish Academy of Learning

(PAU) in 1945 and of the Polish Academy of Sciences

(PAN) in 1952. In 1944, he established the Western Institute

(Instytut Zachodni), an institution dedicated to studying the Polish history of what would become the Recovered Territories

. Initially in Warsaw

, the institute's seat moved to Poznań in 1945. Wojciechowski remained its director until his death in 1955. In 1945, Wojciechowski founded the affiliated journal Przegląd Zachodni ("Western Review") and remained his editor-in-chief until his death in 1955. (An English-language version of the journal under the title Polish Western Affairs was published from 1960 to 1994). From 1948–52, he was also founder and editor-in-chief of the "Journal of Law and History" (Czasopismo Prawno-Historyczne), which continues to exist to this day. In his prologue to the bookseries "Old Polish lands" (1948–1957) he explained the purpose of the volumes to the reader and stressed the Polish aspects of the area's history.

Gregor Thum

emphasizes especially Wojchiechowski's statement:

In 1950, as Poland underwent Stalinization, Wojciechowski was condemned for his "anti-German chauvinism" at a Polish historians conference. Hence the open synthesis of nationalist and communist historiography became less influential, though Polish Marxist publications maintained an anti-German undertone.

Zygmunt Wojciechowski died in Poznań

, Poland

, he was the father of historian Marian Wojciechowski (1927–2006).

In 1984 the Western Institute was eventually named in his honor. In Poland Zygmunt Wojciechowski is recognised today as exceptional historian, and one of people who formed Polish intellectual elites.

Historian

A historian is a person who studies and writes about the past and is regarded as an authority on it. Historians are concerned with the continuous, methodical narrative and research of past events as relating to the human race; as well as the study of all history in time. If the individual is...

and nationalist politician, active in the Second Polish Republic

Second Polish Republic

The Second Polish Republic, Second Commonwealth of Poland or interwar Poland refers to Poland between the two world wars; a period in Polish history in which Poland was restored as an independent state. Officially known as the Republic of Poland or the Commonwealth of Poland , the Polish state was...

. During the Occupation of Poland

Occupation of Poland

Occupation of Poland may refer to:* Partitions of Poland * The German Government General of Warsaw and the Austrian Military Government of Lublin during World War I* Occupation of Poland during World War II...

by Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

he was a member of the Polish underground. Wojciechowski was the co-initiator of the Polish "Western thought" (myśl zachodnia), and headed the Western Institute

Western Institute

The Western Institute in Poznań is a scientific research society focusing on the Western provinces of Poland - Kresy Zachodnie , history, economy and politics of Germany, and the Polish-German relations in history and today.Established by...

in Poznań

Poznan

Poznań is a city on the Warta river in west-central Poland, with a population of 556,022 in June 2009. It is among the oldest cities in Poland, and was one of the most important centres in the early Polish state, whose first rulers were buried at Poznań's cathedral. It is sometimes claimed to be...

.

Biography

Wojciechowski was born in Stryj near LvivLviv

Lviv is a city in western Ukraine. The city is regarded as one of the main cultural centres of today's Ukraine and historically has also been a major Polish and Jewish cultural center, as Poles and Jews were the two main ethnicities of the city until the outbreak of World War II and the following...

(Stryi

Stryi

Stryi is a city located on the left bank of the river Stryi in the Lviv Oblast of western Ukraine . Serving as the administrative center of the Stryi Raion , the city itself is also designated as a separate raion within the oblast. Thus, the city has two administrations - the city and the raion...

, Ukraine

Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It has an area of 603,628 km², making it the second largest contiguous country on the European continent, after Russia...

), then Austro-Hungarian

Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary , more formally known as the Kingdoms and Lands Represented in the Imperial Council and the Lands of the Holy Hungarian Crown of Saint Stephen, was a constitutional monarchic union between the crowns of the Austrian Empire and the Kingdom of Hungary in...

Galicia. In World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

he volunteered Piłsudski’s Legion

Polish Legions in World War I

Polish Legions was the name of Polish armed forces created in August 1914 in Galicia. Thanks to the efforts of KSSN and the Polish members of the Austrian parliament, the unit became an independent formation of the Austro-Hungarian Army...

but was not deployed anymore.

In 1921, Wojciechowski began studying at the Jan Kazimierz University

Lviv University

The Lviv University or officially the Ivan Franko National University of Lviv is the oldest continuously operating university in Ukraine...

in Lwów, which had then just been re-incorporated in the re-created Polish state (now Lviv

Lviv

Lviv is a city in western Ukraine. The city is regarded as one of the main cultural centres of today's Ukraine and historically has also been a major Polish and Jewish cultural center, as Poles and Jews were the two main ethnicities of the city until the outbreak of World War II and the following...

in Ukraine

Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It has an area of 603,628 km², making it the second largest contiguous country on the European continent, after Russia...

). In 1924, he obtained a doctorate in medieval history, social sciences, and economics, and became assistant professor at the Institute for Auxiliary Sciences of History

Auxiliary sciences of history

Auxiliary sciences of history are scholarly disciplines which help evaluate and use historical sources and are seen as auxiliary for historical research...

. In 1924 he published his first concept of the "motherland territories" of Poland. His definition of "Polish motherland" defined them as the areas forming 10th-century Piast Poland in the era of Mieszko I and Boleslaw Krzywousty:Masovia, Lesser Poland

Lesser Poland

Lesser Poland is one of the historical regions of Poland, with its capital in the city of Kraków. It forms the southeastern corner of the country, and should not be confused with the modern Lesser Poland Voivodeship, which covers only a small, southern part of Lesser Poland...

, Greater Poland

Greater Poland

Greater Poland or Great Poland, often known by its Polish name Wielkopolska is a historical region of west-central Poland. Its chief city is Poznań.The boundaries of Greater Poland have varied somewhat throughout history...

, Silesia

Silesia

Silesia is a historical region of Central Europe located mostly in Poland, with smaller parts also in the Czech Republic, and Germany.Silesia is rich in mineral and natural resources, and includes several important industrial areas. Silesia's largest city and historical capital is Wrocław...

, Gdańsk Pomerania

Gdańsk Pomerania

For the medieval duchy, see Pomeranian duchies and dukesGdańsk Pomerania or Eastern Pomerania is a geographical region in northern Poland covering eastern part of Pomeranian Voivodeship...

, Western Pomerania, Neumark

Neumark

Neumark comprised a region of the Prussian province of Brandenburg, Germany.Neumark may also refer to:* Neumark, Thuringia* Neumark, Saxony* Neumark * Nowe Miasto Lubawskie or Neumark, a town in Poland, situated at river Drwęca...

, West Prussia

West Prussia

West Prussia was a province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1773–1824 and 1878–1919/20 which was created out of the earlier Polish province of Royal Prussia...

). In 1925, he moved to Poznań, where he first was the deputy holder of the chair for the history of the political system and Ancient Polish law at Adam Mickiewicz University (UAM). The same year, he completed his habilitation

Habilitation

Habilitation is the highest academic qualification a scholar can achieve by his or her own pursuit in several European and Asian countries. Earned after obtaining a research doctorate, such as a PhD, habilitation requires the candidate to write a professorial thesis based on independent...

with a thesis on the territorial administration of medieval settlements. He became extraordinary (non-tenured) professor in 1929, and full professor in January 1937. From 1939, he was the dean

Dean (education)

In academic administration, a dean is a person with significant authority over a specific academic unit, or over a specific area of concern, or both...

of the university's Department of Law and Economics.

Political activity

Since 1934, Wojciechowski, a friend of Roman DmowskiRoman Dmowski

Roman Stanisław Dmowski was a Polish politician, statesman, and chief ideologue and co-founder of the National Democracy political movement, which was one of the strongest political camps of interwar Poland.Though a controversial personality throughout his life, Dmowski was instrumental in...

(leader of endecja

Endecja

National Democracy was a Polish right-wing nationalist political movement active from the latter 19th century to the end of the Second Polish Republic in 1939. A founder and principal ideologue was Roman Dmowski...

), had been one of the main ideologists of the Camp of Great Poland (OWP). He was active in the right-wing All-Polish Youth and the Liga Narodowa. In 1934 he founded the "League of Young Nationalists" (Związek Młodych Narodowców), whose aim was the foundation of an authoritarian, homogenous Polish state, and became its chairman until 1937. From 1937 to 1939 he was the chairman of the "Nation State Movement" (Ruch Narodowo-Panstwowy) In 1937 he called for a strong national state that would be democratic During his political career he opposed Dmowski and the movement he belonged to sought integration with Józef Piłsudski's sanacja

Sanacja

Sanation was a Polish political movement that came to power after Józef Piłsudski's May 1926 Coup d'État. Sanation took its name from his watchword—the moral "sanation" of the Polish body politic...

faction, hoping that both main political factions in Poland would unite led by interest in well being of Polish nation However, he considered Dmowski one of the most influential persons of his life.

Wojciechowski initially saw "traces of a modern national thought" in the National Socialism. He initially admired Hitler's anti-Jewish policy as a good example for Poland. He accepted the Anschluss

Anschluss

The Anschluss , also known as the ', was the occupation and annexation of Austria into Nazi Germany in 1938....

of Austria and the Munich Agreement

Munich Agreement

The Munich Pact was an agreement permitting the Nazi German annexation of Czechoslovakia's Sudetenland. The Sudetenland were areas along Czech borders, mainly inhabited by ethnic Germans. The agreement was negotiated at a conference held in Munich, Germany, among the major powers of Europe without...

but became more critical of Hitler's politics in the course of time. According to Tomasz Kenar he was alarmed by Hitler's expansionism but accepted the "Anschluss" of Austria, hoping that it would put Italy against Nazi Germany and into the sphere of Polish alliance. Regarding Munich Agreement he saw Czechoslovakia as too closely allied Soviet Union; while Czechs were in his view natural allies of Poles, their close contacts with the Soviets made such alliance impossible. He remained opposed to German annexation of Czechoslovakia, worried that such event would make Polish military situation difficult. Wojciechowski envisioned a Polish-led block in Central Europe composed of Hungary, Romania, Finland, Estonia,Latvia and Lithuania and in close relationship with Italy, that would oppose both German expansionism and Soviet pressure on these states; he wrote that such alliance would "rescue Christianity" from the threat of "Bolshevik communism" and "hitlerite paganism". Later on he focused his attention towards Fascist Italy

Italian Fascism

Italian Fascism also known as Fascism with a capital "F" refers to the original fascist ideology in Italy. This ideology is associated with the National Fascist Party which under Benito Mussolini ruled the Kingdom of Italy from 1922 until 1943, the Republican Fascist Party which ruled the Italian...

, due to his interest in a "strong state", "depending on legal norms, in tradition of Roman law". While nation was for Wojciechowski at time the "greatest good" he didn't exhibit racist ideas or anything that would be similar to German "volkisch" elements in his works. During Nazi German occupation of Poland he along with his family sheltered a Jewish woman and in a 1945 publication he condemned the mass murder of Jews by Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

during the war as "monstrous"

Wojciechowski is described as a co-initiator of the Polish "Western thought" (myśl zachodnia), a "mirror image of the German Ostforschung

Ostforschung

Ostforschung in general describes since the 18th century any German research of areas to the East of Germany. Since the 1990s, the Ostforschung itself is a subject of historic research, while the names of institutes etc. were changed to more specific ones. For example, the journal „Zeitschrift für...

with a pinch of pan-Slavic sentiment thrown in". Unlike Ostforschung this movement was marginal in Poland, and limited only to Poznań University, while the Ostforschung was influential and remained (unlike the Poznań thinkers who were in conflict with state authorities both before and after World War II) in friendly relations with Berlin government.

The Polish researchers rejected the state model found in Germany, and preferred Francoist Spain or Salazar's Portugal, remaining distrustful of Hitler. They rejected such ideas as biological racism, eugenics and militarism and neo-pagan movement.

Fate during German occupation

While initially able to escape Germans, he was captured by them in October 1939 and held as hostageHostage

A hostage is a person or entity which is held by a captor. The original definition meant that this was handed over by one of two belligerent parties to the other or seized as security for the carrying out of an agreement, or as a preventive measure against certain acts of war...

along with other Polish intellectuals, craftsmen, politicians and students. The group was held as part of German effort to crush Polish resistance, and they were threatened with murder in case of armed resistance. Every few days, Wojciechowski was allowed to visit home. If he wouldn't return, the others would be shot. Eventually he was released two months later, due to his pregnant wife's plea. Despite his release, the family faced further reprisals, as it had to flee Poznań

Poznan

Poznań is a city on the Warta river in west-central Poland, with a population of 556,022 in June 2009. It is among the oldest cities in Poland, and was one of the most important centres in the early Polish state, whose first rulers were buried at Poznań's cathedral. It is sometimes claimed to be...

as initial ethnic cleansing

Ethnic cleansing

Ethnic cleansing is a purposeful policy designed by one ethnic or religious group to remove by violent and terror-inspiring means the civilian population of another ethnic orreligious group from certain geographic areas....

of Poles from the region was initiated by Nazi German authorities. Wojciechowski eventually found refugee at a friend's house in Kraków.

Underground activity

During the occupation of Poland in World War IIWorld War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

, he was involved with the Polish underground authorities, teaching at the Uniwersytet Ziem Zachodnich ("University of the Western Territories", a part of the necessary underground education system

Education in Poland during World War II

This article covers the topic of underground education in Poland during World War II. Secret learning prepared new cadres for the post-war reconstruction of Poland and countered the German and Soviet threat to exterminate the Polish culture....

) necessary, as all Poles were forbidden basic schooling as part of German genocide

Genocide

Genocide is defined as "the deliberate and systematic destruction, in whole or in part, of an ethnic, racial, religious, or national group", though what constitutes enough of a "part" to qualify as genocide has been subject to much debate by legal scholars...

regarding Polish nation. He continued his research, and supervised his students (Zdzisław Kaczmarczyk, Kazimierz Kolańczyk) who finished two dissertations. In 1944 He also headed the Government Delegation for Poland's Science Section in the Department of Information, and briefly, after the fall of the Warsaw Uprising

Warsaw Uprising

The Warsaw Uprising was a major World War II operation by the Polish resistance Home Army , to liberate Warsaw from Nazi Germany. The rebellion was timed to coincide with the Soviet Union's Red Army approaching the eastern suburbs of the city and the retreat of German forces...

, he was the deputy director of the Department. As part of conspiracy during Nazi German occupation he was one of the founding members of Ojczyzna-Omega, a conspiracy movement that gathered surviving (as Germans carried out systematic extermination of Polish educated classes) Polish intellectuals, priests, journalists, lawyers and teachers, who organised charity work, secret education and worked on concepts of post-war Poland; most of the members were Christian democrats and national democrats

National Democrats

There are a number of political parties operating in various countries with the name National Democrats.* National Democrats * National Democrats * National Democrats * National Democrats...

. Ojczyzna-Omega envisioned a post-war Poland that would be a democratic, efficiently administrated state populated mainly by Polish majority alongside Jewish population and Slavic groups. The organisation believed that Nazi Germany(which attempted a genocide of Poles) was far more dangerous than Soviet Union and pushed for a compromise with Soviets.

Commissioned by the Union of Armed Struggle, a forerunner of the Home Army, Wojciechowski created a concept of a post-war Polish–German border in 1941, which included an overview of the Polish and Polonizable part of the population in areas between the pre-war border and the Oder-Neisse line

Oder-Neisse line

The Oder–Neisse line is the border between Germany and Poland which was drawn in the aftermath of World War II. The line is formed primarily by the Oder and Lusatian Neisse rivers, and meets the Baltic Sea west of the seaport cities of Szczecin and Świnoujście...

. In tune with and probably in charge of Wojciechowski the director of the library of Kórnik

Kórnik

Kórnik is a town with about 6,800 inhabitants , located in western Poland, approximately south-east of the city of Poznań. It is one of the major tourist attractions of the Wielkopolska region....

at that time prepared the takeover of archives, museums and libraries in the future Western territories. In his designs Wojciechowski wanted to avoid what he defined as the mistakes of the Versailles Treaty. The border at Oder and Lusatian Neisse was essential for him, as he considered it, the historical argument was not decisive here, the safest and most defensible one.

On 17 December 1944 Tomasz Arciszewski

Tomasz Arciszewski

Tomasz Arciszewski was a Polish socialist politician, a member of the Polish Socialist Party and the Prime Minister of the Polish government-in-exile in London from 1944 to 1947, presiding over the period when the government lost the recognition of the Western powers.-Early life:Tomasz Arciszewski...

, the Polish Prime Minister of the Polish government-in-exile in London, declared in a Sunday Times interview, that a post-war Poland had no territorial claims towards Stettin (Szczecin) and Breslau (Wrocław) but considers Lviv

Lviv

Lviv is a city in western Ukraine. The city is regarded as one of the main cultural centres of today's Ukraine and historically has also been a major Polish and Jewish cultural center, as Poles and Jews were the two main ethnicities of the city until the outbreak of World War II and the following...

and Wilna an integral part of the Polish state. This led to a vote of no confidence of the Ojczyzna-group against Arciszewski for this "renunciation of the Polish war aims" and finally to the breakup with the Polish government-in-exile in London. Also in December 1944 he resumed the consequences of the failed Warsaw Uprising

Warsaw Uprising

The Warsaw Uprising was a major World War II operation by the Polish resistance Home Army , to liberate Warsaw from Nazi Germany. The rebellion was timed to coincide with the Soviet Union's Red Army approaching the eastern suburbs of the city and the retreat of German forces...

that, fom his view, had shown, that not the Home Army but only the Red Army

Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army started out as the Soviet Union's revolutionary communist combat groups during the Russian Civil War of 1918-1922. It grew into the national army of the Soviet Union. By the 1930s the Red Army was among the largest armies in history.The "Red Army" name refers to...

was capable to liberate Warsaw.

On 13 February 1945 Wojciechowski met the Prime Minister of the Provisional Government of the Republic of Poland, Edward Osóbka-Morawski

Edward Osóbka-Morawski

Edward Osóbka-Morawski was a Polish activist in PPS before World War II, and after the Soviet takover of Poland, Chairman of the Communist interim government called the Polish Committee of National Liberation formed in Lublin with Stalin's approval and backing.In October 1944, Osóbka-Morawski...

, and handed over a memorandum about the foundation and activities of the Western Institute in which he asked for the support of the institute. The memorandum was addressed to the “Polish government”, thus recognizing the Provisional Government, contrary to the London exile-government, as legitimate.

Conversely Wojciechowski's concept aided the governmental demand to legitimize the Polish acquirements in the West

Post-war

Wojciechowski supported a new German-Polish border that would allocate the whole Oder Lagoon up to the river Peene"There is a new epoch of Slavic march to the west that has replaced the German Drang nach Osten

Drang nach OstenDrang nach Osten was a term coined in the 19th century to designate German expansion into Slavic lands. The term became a motto of the German nationalist movement in the late nineteenth century...

. Who doesn’t understand it, won’t understand the new era and won’t see properly the place of Poland in the new international reality”

Peene

The Peene is a river in Germany. The Westpeene, Kleine Peene and Ostpeene flow into the Kummerower See, and from there as Peene proper to Anklam and into the Oder Lagoon....

to Poland.

He resumed teaching at UAM. He became a member of the Polish Academy of Learning

Polish Academy of Learning

The Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences or Polish Academy of Learning , headquartered in Kraków, is one of two institutions in contemporary Poland having the nature of an academy of sciences....

(PAU) in 1945 and of the Polish Academy of Sciences

Polish Academy of Sciences

The Polish Academy of Sciences, headquartered in Warsaw, is one of two Polish institutions having the nature of an academy of sciences.-History:...

(PAN) in 1952. In 1944, he established the Western Institute

Western Institute

The Western Institute in Poznań is a scientific research society focusing on the Western provinces of Poland - Kresy Zachodnie , history, economy and politics of Germany, and the Polish-German relations in history and today.Established by...

(Instytut Zachodni), an institution dedicated to studying the Polish history of what would become the Recovered Territories

Recovered Territories

Recovered or Regained Territories was an official term used by the People's Republic of Poland to describe those parts of pre-war Germany that became part of Poland after World War II...

. Initially in Warsaw

Warsaw

Warsaw is the capital and largest city of Poland. It is located on the Vistula River, roughly from the Baltic Sea and from the Carpathian Mountains. Its population in 2010 was estimated at 1,716,855 residents with a greater metropolitan area of 2,631,902 residents, making Warsaw the 10th most...

, the institute's seat moved to Poznań in 1945. Wojciechowski remained its director until his death in 1955. In 1945, Wojciechowski founded the affiliated journal Przegląd Zachodni ("Western Review") and remained his editor-in-chief until his death in 1955. (An English-language version of the journal under the title Polish Western Affairs was published from 1960 to 1994). From 1948–52, he was also founder and editor-in-chief of the "Journal of Law and History" (Czasopismo Prawno-Historyczne), which continues to exist to this day. In his prologue to the bookseries "Old Polish lands" (1948–1957) he explained the purpose of the volumes to the reader and stressed the Polish aspects of the area's history.

Gregor Thum

Gregor Thum

Gregor Thum is a German historian of Central and Eastern Europe.From 1988 through 1995, Thum studied history and Slavic studies at the Free University of Berlin. From 1995 to 2001, he was a lecturer at professor Karl Schlögel's chair for East European history at Viadrina European University in...

emphasizes especially Wojchiechowski's statement:

"Our publication ... is biased; in fact, it is consciously biased. ... We have not gone out of our way to write so-called objective history. Our task was to present the Polish history of those territories and to place the modern Polish reality of those territories within this historical context."

In 1950, as Poland underwent Stalinization, Wojciechowski was condemned for his "anti-German chauvinism" at a Polish historians conference. Hence the open synthesis of nationalist and communist historiography became less influential, though Polish Marxist publications maintained an anti-German undertone.

Zygmunt Wojciechowski died in Poznań

Poznan

Poznań is a city on the Warta river in west-central Poland, with a population of 556,022 in June 2009. It is among the oldest cities in Poland, and was one of the most important centres in the early Polish state, whose first rulers were buried at Poznań's cathedral. It is sometimes claimed to be...

, Poland

Poland

Poland , officially the Republic of Poland , is a country in Central Europe bordered by Germany to the west; the Czech Republic and Slovakia to the south; Ukraine, Belarus and Lithuania to the east; and the Baltic Sea and Kaliningrad Oblast, a Russian exclave, to the north...

, he was the father of historian Marian Wojciechowski (1927–2006).

Recognition

He was a recipient of Commander's Cross and Officer's Cross of Order of Polonia Restituta.In 1984 the Western Institute was eventually named in his honor. In Poland Zygmunt Wojciechowski is recognised today as exceptional historian, and one of people who formed Polish intellectual elites.

Publications

- Ustrój polityczny ziem polskich w czasach przedpiastowskich Lwów 1927

- Początki immunitetu w Polsce 1930

- Polska nad Wisłą i Odrą w X wieku. Studium nad genezą państwa Piastów i jego cywilizacji [Poland on the Vistula and Oder in the 10th century: A study on the genesis of the Piast state and its civilization], Warszawa: Nasza Księgarnia, 1939

- Państwo polskie w wiekach średnich. Dzieje ustroju 1945

- Polska-Niemcy. Dziesięć wieków zmagania [Poland-Germany. Ten centuries of struggle]. Poznań: Wydawnictwo Instytutu Zachodniego, 1945

- Polska-Czech. Dziesięć wieków sąsiedztwa Poland-Czechs. Ten centuries of neighbourhood. 1947(with Tadeusz Lehr-Spławiński, Kazimierz Piwiarski)

- Państwo polskie w wiekach średnich. Dzieje ustroju [The Polish state in the Middle Ages: The history of its political system], Poznań: Poznań Księgarnia Akademicka, 1948

- Zygmunt Stary (1506-1548) [ Sigismund the Old (1506–1548)], 1946, re-issue Warszawa: Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy, 1979

- (as editor) Poland's Place in Europe. Poznań: Wydawnictwo Instytutu Zachodniego, 1947

Further reading

- Markus Krzoszka, Für ein Polen an Oder und Ostsee. Zygmunt Wojciechowski (1900-1955) als Historiker und Publizist, Osnabrück: fibre, 2003. ISBN 3-929759-49-7