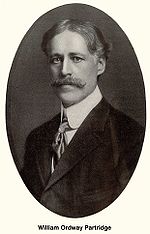

William Ordway Partridge

Encyclopedia

Sculpture

Sculpture is three-dimensional artwork created by shaping or combining hard materials—typically stone such as marble—or metal, glass, or wood. Softer materials can also be used, such as clay, textiles, plastics, polymers and softer metals...

whose public commissions can be found in New York City and other locations.

William Partridge was born in Paris to American parents descended from the Pilgrims in Massachusetts; his father was a representative of A.T. Stewart

Alexander Turney Stewart

Alexander Turney Stewart was a successful Irish American entrepreneur who made his multi-million fortune in what was at the time the most extensive and lucrative dry goods business in the world....

. At the end of the reign of Napoleon III, Partridge travelled to America to attend Adelphi Academy in Brooklyn and Columbia University

Columbia University

Columbia University in the City of New York is a private, Ivy League university in Manhattan, New York City. Columbia is the oldest institution of higher learning in the state of New York, the fifth oldest in the United States, and one of the country's nine Colonial Colleges founded before the...

(graduated 1883) in New York. After a year of experimention in theatre, he went abroad to study sculpture. During a brief stint in the Paris studio of William-Adolphe Bouguereau

William-Adolphe Bouguereau

William-Adolphe Bouguereau was a French academic painter. William Bouguereau was a traditionalist; in his realistic genre paintings he used mythological themes, making modern interpretations of Classical subjects, with an emphasis on the female human body.-Life and career :William-Adolphe...

, he formed a close friendship with the neo-Gothic architect Ralph Adams Cram

Ralph Adams Cram

Ralph Adams Cram FAIA, , was a prolific and influential American architect of collegiate and ecclesiastical buildings, often in the Gothic style. Cram & Ferguson and Cram, Goodhue & Ferguson are partnerships in which he worked.-Early life:Cram was born on December 16, 1863 at Hampton Falls, New...

on his 1887 trip. He knew the young Bernard Berenson

Bernard Berenson

Bernard Berenson was an American art historian specializing in the Renaissance. He was a major figure in pioneering art attribution and therefore establishing the market for paintings by the "Old Masters".-Personal life:...

in Florence, where he studied in the studio of Galli, and Rome, in the studio of Pio Welonski (1883–85).

His published work includes articles on aesthetics

Aesthetics

Aesthetics is a branch of philosophy dealing with the nature of beauty, art, and taste, and with the creation and appreciation of beauty. It is more scientifically defined as the study of sensory or sensori-emotional values, sometimes called judgments of sentiment and taste...

and several art history books including Art For America (1894), The Song Life of a Sculptor (1894), and The Technique of Sculpture (1895). He also wrote poems and published the verse novels Angel of Clay (1900) and The Czar's Gift (1906).

Aside from his public commissions, his work consisted mostly of portrait busts. In 1893 eleven of his works were displayed at the World's Columbian Exposition

World's Columbian Exposition

The World's Columbian Exposition was a World's Fair held in Chicago in 1893 to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus's arrival in the New World in 1492. Chicago bested New York City; Washington, D.C.; and St...

, Chicago, according to the official catalog of the Fine Arts Building at the fair, where he exhibited sculptures of Alexander Hamilton and William Shakespeare as well as portraits. In this same catalog Partridge was listed as living in Milton, Massachusetts

Milton, Massachusetts

Milton is a town in Norfolk County, Massachusetts, United States and part of the Greater Boston area. The population was 27,003 at the 2010 census. Milton is the birthplace of former U.S. President George H. W. Bush and architect Buckminster Fuller. Milton also has the highest percentage of...

. He maintained homes and studios in both Milton and New York. Among his studio assistants on West 38th Street in New York was Lee Lawrie

Lee Lawrie

Lee Oscar Lawrie was one of the United States' foremost architectural sculptors and a key figure in the American art scene preceding World War II...

.

Partridge went on to lecture at Stanford University

Stanford University

The Leland Stanford Junior University, commonly referred to as Stanford University or Stanford, is a private research university on an campus located near Palo Alto, California. It is situated in the northwestern Santa Clara Valley on the San Francisco Peninsula, approximately northwest of San...

in California, and assumed a professor

Professor

A professor is a scholarly teacher; the precise meaning of the term varies by country. Literally, professor derives from Latin as a "person who professes" being usually an expert in arts or sciences; a teacher of high rank...

ship at Columbian University, now George Washington University

George Washington University

The George Washington University is a private, coeducational comprehensive university located in Washington, D.C. in the United States...

, in Washington, D.C.

His life-size statue of the Native American

Native Americans in the United States

Native Americans in the United States are the indigenous peoples in North America within the boundaries of the present-day continental United States, parts of Alaska, and the island state of Hawaii. They are composed of numerous, distinct tribes, states, and ethnic groups, many of which survive as...

Indian princess, Pocahontas

Pocahontas

Pocahontas was a Virginia Indian notable for her association with the colonial settlement at Jamestown, Virginia. She was the daughter of Chief Powhatan, the head of a network of tributary tribal nations in Tidewater Virginia...

, was unveiled in Jamestown, Virginia

Jamestown, Virginia

Jamestown was a settlement in the Colony of Virginia. Established by the Virginia Company of London as "James Fort" on May 14, 1607 , it was the first permanent English settlement in what is now the United States, following several earlier failed attempts, including the Lost Colony of Roanoke...

in 1922. Queen Elizabeth II viewed this statue in 1957 and again on May 4, 2007, while visiting Jamestown on the 400th anniversary of the founding of the first successful English colonial settlement in America. On October 5, 1958, a replica of the Pocahontas statue by Partridge was dedicated as a memorial to the princess at the location of her burial in 1617 at St. George's Church in Gravesend, England. The Governor of Virginia presented the replica statue as a gift to the British people.

Partridge died in New York in 1930.

Selected works

A considerable amount of Partridge's statuary remains on public display in New York City and other locations:- Samuel J. TildenSamuel J. TildenSamuel Jones Tilden was the Democratic candidate for the U.S. presidency in the disputed election of 1876, one of the most controversial American elections of the 19th century. He was the 25th Governor of New York...

, on Riverside Drive at 113th Street. - Thomas JeffersonThomas JeffersonThomas Jefferson was the principal author of the United States Declaration of Independence and the Statute of Virginia for Religious Freedom , the third President of the United States and founder of the University of Virginia...

, in front of Journalism Hall at Columbia UniversityColumbia UniversityColumbia University in the City of New York is a private, Ivy League university in Manhattan, New York City. Columbia is the oldest institution of higher learning in the state of New York, the fifth oldest in the United States, and one of the country's nine Colonial Colleges founded before the...

. - Thomas JeffersonThomas JeffersonThomas Jefferson was the principal author of the United States Declaration of Independence and the Statute of Virginia for Religious Freedom , the third President of the United States and founder of the University of Virginia...

, New York Historic Society, 1901. - Alexander HamiltonAlexander HamiltonAlexander Hamilton was a Founding Father, soldier, economist, political philosopher, one of America's first constitutional lawyers and the first United States Secretary of the Treasury...

, Hamilton Grange, New York, (1892.) This standing figure was commissioned by the Hamilton Club of Brooklyn and having been exhibited at the World's Columbian Exposition, stood in front of the Club's premises in Brooklyn Heights, 1893–1936, when it was removed to its present location. A replica erected 1908 stands in front of Hamilton Hall, Columbia University. - Edward Everett HaleEdward Everett HaleEdward Everett Hale was an American author, historian and Unitarian clergyman. He was a child prodigy who exhibited extraordinary literary skills and at age thirteen was enrolled at Harvard University where he graduated second in his class...

, bust, Union League Club of Chicago. (Appleton's Cyclopaedia) - A bust of DeanDean (education)In academic administration, a dean is a person with significant authority over a specific academic unit, or over a specific area of concern, or both...

John Howard Van AmringeJohn Howard Van AmringeJohn Howard Van Amringe was a U.S. educator and mathematician. He was born in Philadelphia, and graduated from Columbia in 1860. Thereafter, he taught mathematics at Columbia, holding a professorship from 1865 to 1910 when he retired...

at Columbia University. - Nathan Hale

- The marble memorial plaque showing the likeness of James SmithsonJames SmithsonJames Smithson, FRS, M.A. was a British mineralogist and chemist noted for having left a bequest in his will to the United States of America, to create "an establishment for the increase and diffusion of knowledge among men" to be called the Smithsonian Institution.-Biography:Not much is known...

in the crypt room where Smithson's tomb is located, inside The Castle Building of the Smithsonian InstitutionSmithsonian InstitutionThe Smithsonian Institution is an educational and research institute and associated museum complex, administered and funded by the government of the United States and by funds from its endowment, contributions, and profits from its retail operations, concessions, licensing activities, and magazines...

, Washington, D.C., 1900. The original of this work is in Genoa, Italy, where Smithson died. - The Resurrection, marble bas-relief for the National Cathedral, Washington, D.C., 1902.

- The marbleMarbleMarble is a metamorphic rock composed of recrystallized carbonate minerals, most commonly calcite or dolomite.Geologists use the term "marble" to refer to metamorphosed limestone; however stonemasons use the term more broadly to encompass unmetamorphosed limestone.Marble is commonly used for...

PietàPietàThe Pietà is a subject in Christian art depicting the Virgin Mary cradling the dead body of Jesus, most often found in sculpture. As such, it is a particular form of the Lamentation of Christ, a scene from the Passion of Christ found in cycles of the Life of Christ...

at St. Patrick's CathedralSt. Patrick's Cathedral, New YorkThe Cathedral of St. Patrick is a decorated Neo-Gothic-style Roman Catholic cathedral church in the United States...

. - The equestrianEquestrian sculptureAn equestrian statue is a statue of a rider mounted on a horse, from the Latin "eques", meaning "knight", deriving from "equus", meaning "horse". A statue of a riderless horse is strictly an "equine statue"...

statue of General Ulysses S. GrantUlysses S. GrantUlysses S. Grant was the 18th President of the United States as well as military commander during the Civil War and post-war Reconstruction periods. Under Grant's command, the Union Army defeated the Confederate military and ended the Confederate States of America...

, commissioned by the Union Club of Brooklyn and unveiled April 27, 1896, in Grant Square, at Bedford Avenue and Dean Street, Crown Heights, BrooklynBrooklynBrooklyn is the most populous of New York City's five boroughs, with nearly 2.6 million residents, and the second-largest in area. Since 1896, Brooklyn has had the same boundaries as Kings County, which is now the most populous county in New York State and the second-most densely populated...

. - The bust of Theodore RooseveltTheodore RooseveltTheodore "Teddy" Roosevelt was the 26th President of the United States . He is noted for his exuberant personality, range of interests and achievements, and his leadership of the Progressive Movement, as well as his "cowboy" persona and robust masculinity...

at the Republican Club. - The marble "Peace Head" at the Metropolitan Museum of ArtMetropolitan Museum of ArtThe Metropolitan Museum of Art is a renowned art museum in New York City. Its permanent collection contains more than two million works, divided into nineteen curatorial departments. The main building, located on the eastern edge of Central Park along Manhattan's Museum Mile, is one of the...

, New York. - Anne's Tablet, memorial to Constance Fenimore WoolsonConstance Fenimore WoolsonConstance Fenimore Woolson was an American novelist and short story writer. She was a grandniece of James Fenimore Cooper, and is best known for fictions about the Great Lakes region, the American South, and American expatriates in Europe.-In America: the story-writer:Woolson was born in...

, Mackinac IslandMackinac IslandMackinac Island is an island and resort area covering in land area, part of the U.S. state of Michigan. It is located in Lake Huron, at the eastern end of the Straits of Mackinac, between the state's Upper and Lower Peninsulas. The island was home to a Native American settlement before European...

, Michigan - Pietà, St. Patrick's CathedralSt. Patrick's Cathedral, New YorkThe Cathedral of St. Patrick is a decorated Neo-Gothic-style Roman Catholic cathedral church in the United States...

, New York, transept. - The Samuel H. Kauffman MemorialKauffmann MemorialKauffmann Memorial is a public artwork by American artist William Ordway Partridge, located at Rock Creek Cemetery in Washington, D.C., United States. Kauffmann Memorial was originally surveyed as part of the Smithsonian's Save Outdoor Sculpture! survey in 1993...

ca. 1921, Rock Creek Cemetery, Washington, D.C. A seated bronze figure on a marble exedra with bronze bas-reliefs of the Serven Ages of Man after Shakespeare. - The Joseph PulitzerJoseph PulitzerJoseph Pulitzer April 10, 1847 – October 29, 1911), born Politzer József, was a Hungarian-American newspaper publisher of the St. Louis Post Dispatch and the New York World. Pulitzer introduced the techniques of "new journalism" to the newspapers he acquired in the 1880s and became a leading...

MemorialMemorialA memorial is an object which serves as a focus for memory of something, usually a person or an event. Popular forms of memorials include landmark objects or art objects such as sculptures, statues or fountains, and even entire parks....

(1913) in Woodlawn CemeteryWoodlawn Cemetery, BronxWoodlawn Cemetery is one of the largest cemeteries in New York City and is a designated National Historic Landmark.A rural cemetery located in the Bronx, it opened in 1863, in what was then southern Westchester County, in an area that was annexed to New York City in 1874.The cemetery covers more...

, The Bronx. Seated mourning figure. - Memory 1914. Memorial Art Gallery, Rochester, New York.

Affiliations

- Architectural League of New YorkArchitectural League of New YorkThe Architectural League of New York is a non-profit organization "for creative and intellectual work in architecture, urbanism, and related disciplines"....

- Sons of the American RevolutionSons of the American RevolutionThe National Society of the Sons of the American Revolution is a Louisville, Kentucky-based fraternal organization in the United States...

- Veteran Corps of Artillery, State of New York

- American Institute of ArchitectsAmerican Institute of ArchitectsThe American Institute of Architects is a professional organization for architects in the United States. Headquartered in Washington, D.C., the AIA offers education, government advocacy, community redevelopment, and public outreach to support the architecture profession and improve its public image...

(honorary) - Royal Society of ArtsRoyal Society of ArtsThe Royal Society for the encouragement of Arts, Manufacturers and Commerce is a British multi-disciplinary institution, based in London. The name Royal Society of Arts is frequently used for brevity...

, London - He was also a member of the literary and artistic Lotos ClubLotos ClubThe Lotos Club is a gentleman's club in New York City. Founded in 1870 by a young group of writers and critics, Mark Twain, an early member, called it the "Ace of Clubs"...

, New York