Robert Watson-Watt

Encyclopedia

Sir Robert Alexander Watson-Watt, KCB

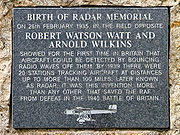

, FRS, FRAeS (13 April 1892 – 5 December 1973) is considered by many to be the "inventor of radar

". (The hyphenated name is used herein for consistency, although this was not adopted until he was knighted in 1942.) Development of radar

, initially nameless, was first started elsewhere but greatly expanded on 1 September 1936 when Watson-Watt became Superintendent of a new establishment under the British

Air Ministry

, Bawdsey Research Station

located in Bawdsey Manor

, near Felixstowe

, Suffolk

. Work there resulted in the design and installation of aircraft detection and tracking stations called Chain Home

along the East and South coasts of England in time for the outbreak of World War II in 1939. This system provided the vital advance information that helped the Royal Air Force win the Battle of Britain

.

, Angus

, Scotland

, Watson-Watt was a descendant of James Watt

, the famous engineer and inventor of the practical steam engine

. After attending Damacre Primary School and Brechin High School

, he was accepted to University College, Dundee (which was then part of the University of St Andrews

but became the University of Dundee

in 1967). Watt had a successful time as a student, winning the Carnelley Prize for Chemistry and a class medal for Ordinary Natural Philosophy in 1910.

He graduated with a BSc

in engineering in 1912, and was offered an assistantship by Professor William Peddie, the holder of the Chair of Physics at University College, Dundee

from 1907 to 1942. It was Peddie who encouraged Watson-Watt to study radio, or "wireless telegraphy" as it was then known and who took him through what was effectively a postgraduate class of one on the physics of radio frequency oscillators and wave propagation. At the start of the Great War Watson-Watt was working as an assistant in the College's Engineering Department.

In 1949 a Watson-Watt Chair of Electrical Engineering was established at University College, Dundee

.

, but nothing obvious was available in communications. Instead he joined the Meteorological Office

, who were interested in his ideas on the use of radio for the detection of thunderstorm

s. Lightning

gives off a radio signal as it ionizes the air, and he planned on detecting this signal in order to warn pilots of approaching thunderstorms.

His early experiments were successful in detecting the signal, and he quickly proved to be able to do so at long ranges. Two problems remained however. The first was locating the signal, and thus the direction to the storm. This was solved with the use of a directional antenna, which could be manually turned to maximize (or minimize) the signal, thus "pointing" to the storm. Once this was solved the equally difficult problem of actually seeing the fleeting signal became obvious, which he solved with the use of a cathode-ray oscilloscope

with a long-lasting phosphor

. Such a system represented a significant part of a complete radar system, and was in use as early as 1923. It would, however, need the addition of a pulsed transmitter and a method of measuring the time delay of the received radio echos, and that would in time come from work on ionosonde

s.

At first he worked at the Wireless Station of Air Ministry Meteorological Office in Aldershot

, England

. In 1924 when the War Department gave notice that they wished to re-occupy their Aldershot site, he moved to Ditton Park

near Slough

in Berkshire

. The National Physical Laboratory

(NPL) already had a research station there. In 1927 they were amalgamated as the Radio Research Station

, with Watson-Watt in charge. After a further re-organisation in 1933, Watson-Watt became Superintendent of the Radio Department of NPL in Teddington

.

to advance the state of the art of air defence in the UK. During World War I

, the Germans had used Zeppelin

s as long-range bombers over London and other cities and defences had struggled to counter the threat. Since that time aircraft capabilities had improved considerably, and existing weapons were unlikely to have any effect on a raid.

The prospect of aerial bombardment of civilian areas was causing the government anxiety with heavy bombers able to approach from altitudes that anti-aircraft guns of the day were unable to reach. With the enemy airfields only 20 minutes away, the bombers would have dropped their bombs and be returning to base before the intercepting fighters could get to altitude. The only solution would be to have standing patrols of fighters in the air at all times, but with the limited cruising time of a fighter this would require a gigantic standing force. A plausible solution was urgently needed.

Nazi Germany

was rumored to have a "death-ray

" using radio waves that was capable of destroying towns, cities and people. In January 1935, H.E. Wimperis, Director of Scientific Research at the Air Ministry, asked Watson-Watt about the possibly of building their version of a death-ray, specifically to be used against aircraft. Watson-Watt quickly returned a calculation carried out by his assistant, Arnold Wilkins

, showing that the device was impossible to construct, and fears of a Nazi version soon vanished. However he also mentioned in the same report: "Meanwhile attention is being turned to the still difficult, but less unpromising, problem of radio detection and numerical considerations on the method of detection by reflected radio waves will be submitted when required."

On 12 February 1935, Watson-Watt sent a secret memo of the proposed system to the Air Ministry

On 12 February 1935, Watson-Watt sent a secret memo of the proposed system to the Air Ministry

, entitled Detection and location of aircraft by radio methods. Although not as exciting as a death-ray, the concept clearly had potential but the Air Ministry, before giving funding, asked for a demonstration proving that radio waves could be reflected by an aircraft. This was ready by 26 February and consisted of two receiving antennas located about ten km away from one of the BBC

's shortwave broadcast stations at Daventry

. The two antennas were phased such that signals travelling directly from the station cancelled themselves out, but signals arriving from other angles were admitted, thereby deflecting the trace on a CRT

indicator (passive radar

). Such was the secrecy of this test that only three people witnessed it: Watson-Watt, his assistant Arnold Wilkins, and a single member of the committee, A.P. Rowe. The demonstration was a success; on several occasions a clear signal was seen from a Handley Page Heyford

bomber being flown around the site. Most importantly, the prime minister, Stanley Baldwin

, was kept quietly informed of radar's progress. On 2 April 1935, Watson-Watt received a patent on a radio device for detecting and locating an aircraft.

In mid-May 1935, Wilkins left the Radio Research Station with a small party, including Edward George Bowen

, to start further research at Orford Ness

, an isolated peninsula on the coast of the North Sea. By June they were detecting aircraft at 27 km, which was enough for scientists and engineers to stop all work on competing sound-based detection systems

. By the end of the year the range was up to 100 km, at which point plans were made in December to set up five stations covering the approaches to London.

One of these stations was to be located on the coast near Orford Ness, and Bawdsey Manor

was selected to become the main centre for all radar research. In an effort to put a radar defense in place as quickly as possible, Watson-Watt and his team created devices using existing available components, rather than creating new components for the project, and the team did not take additional time to refine and improve the devices. So long as the prototype radars were in workable condition they were put into production. They soon conducted "full scale" tests of a fixed radar radio tower

system that would soon be known as Chain Home

, an early detection system that attempted to detect an incoming bomber by radio signals. The tests were a complete failure, with the fighter only seeing the bomber after it had passed its target. The problem was not the radar, but the flow of information from trackers from the Observer Corps to the fighters, which took many steps and was very slow. Henry Tizard

with Patrick Blackett and Hugh Dowding immediately set to work on this problem, designing a 'command and control air defence reporting system' with several layers of reporting that were eventually sent to a single large room for mapping. Observers watching the maps would then tell the fighter groups what to do via direct communications.

By 1937 the first three stations were ready and the associated system was put to the test. The results were encouraging and an immediate order by the government to commission an additional 17 stations was given, resulting in a chain of fixed radar towers along the east and south coast of England. By the start of World War II, 19 were ready to play a key part in the Battle of Britain

, and by the end of the war over 50 had been built. The Germans were aware of the construction of Chain Home but were not sure of its purpose. They tested their theories with a flight of the Zeppelin

LZ 130

, but concluded the stations were a new long-range naval communications system.

As early as 1936, it was realized that the Luftwaffe

would turn to night bombing if the day campaign did not go well, and Watson-Watt had put another of the staff from the Radio Research Station, Edward Bowen, in charge of developing a radar that could be carried by a fighter. Night time visual detection of a bomber was good to about 300 m, and the existing Chain Home systems simply didn't have the accuracy needed to get the fighters that close. Bowen decided that an airborne radar should not exceed 90 kg

(200 lb

in weight, 8 ft³ (230 L

) in volume, and require no more than 500 watts of power. To reduce the drag of the antennas the operating wavelength could not be much greater than one m, difficult for the day's electronics. "AI" - Airborne Interception, was perfected by 1940, and was instrumental in eventually ending the Blitz

of 1941. Bowen also fitted airborne radar to maritime patrol aircraft (known in this application as "ASV" - Air to Surface Vessel) and this eventually reduced the threat from submarines.

In his English History 1914-1945, historian A. J. P. Taylor

In his English History 1914-1945, historian A. J. P. Taylor

paid the highest of praise to Watson-Watt, Sir Henry Tizard

and their associates who developed and put in place radar, crediting them with being fundamental to victory in World War II

.

In July 1938 Watson-Watt left Bawdsey Manor and took up the post of Director of Communications Development (DCD-RAE). In 1939 Sir George Lee took over the job of DCD, and Watson-Watt became Scientific Advisor on Telecommunications (SAT) to the Air Ministry

, travelling to the USA

in 1941 in order to advise them on the severe inadequacies of their air defence efforts illustrated by the Pearl Harbor attack. His contributions to the war effort were so significant that he was knighted in 1942.

Ten years after his knighthood, Watson-Watt was awarded £50,000 by the British government for his contributions in the development of radar. He established a practice as a consulting engineer. In the 1950s moved to Canada

. Later he lived in the USA, where he published Three Steps to Victory in 1958. Around 1958 he appeared as a mystery challenger on the American

television programme To Tell The Truth

.

On one occasion, late in life, Watson-Watt reportedly was pulled over in Canada for speeding by a radar-gun toting policeman. His remark was, "Had I known what you were going to do with it I would never have invented it!" He wrote an ironic poem ("Rough Justice") afterwards:

He returned to Scotland in the 1960s. In 1966, at the age of 72, he proposed to Dame Katherine Trefusis Forbes, who was 67 years old at the time and had also played a significant role in the Battle of Britain

as the founding Air Commander of the Womens Auxiliary Air Force, which supplied the radar-room operatives. They lived together in London in the winter, and at "The Observatory" – Trefusis Forbes' summer home in Pitlochry

, Perthshire

, during the warmer months. They remained together until her death in 1971. Watson-Watt died in 1973, aged 81, in Inverness

. Both are buried in the church yard of the Episcopal Church of the Holy Trinity at Pitlochry.

Order of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry founded by George I on 18 May 1725. The name derives from the elaborate mediæval ceremony for creating a knight, which involved bathing as one of its elements. The knights so created were known as Knights of the Bath...

, FRS, FRAeS (13 April 1892 – 5 December 1973) is considered by many to be the "inventor of radar

Radar

Radar is an object-detection system which uses radio waves to determine the range, altitude, direction, or speed of objects. It can be used to detect aircraft, ships, spacecraft, guided missiles, motor vehicles, weather formations, and terrain. The radar dish or antenna transmits pulses of radio...

". (The hyphenated name is used herein for consistency, although this was not adopted until he was knighted in 1942.) Development of radar

History of radar

The history of radar starts with experiments by Heinrich Hertz in the late 19th century that showed that radio waves were reflected by metallic objects. This possibility was suggested in James Clerk Maxwell's seminal work on electromagnetism...

, initially nameless, was first started elsewhere but greatly expanded on 1 September 1936 when Watson-Watt became Superintendent of a new establishment under the British

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

Air Ministry

Air Ministry

The Air Ministry was a department of the British Government with the responsibility of managing the affairs of the Royal Air Force, that existed from 1918 to 1964...

, Bawdsey Research Station

RAF Bawdsey

RAF Bawdsey was an RAF station situated on the eastern coast in Suffolk, England.Bawdsey Manor, dating from 1886, was taken over in March 1936 by the Air Ministry for developing the Chain Home RDF system...

located in Bawdsey Manor

Bawdsey Manor

Bawdsey Manor stands at a prominent position at the mouth of the River Deben close to the village of Bawdsey in Suffolk, England, about 118 km northeast of London....

, near Felixstowe

Felixstowe

Felixstowe is a seaside town on the North Sea coast of Suffolk, England. The town gives its name to the nearby Port of Felixstowe, which is the largest container port in the United Kingdom and is owned by Hutchinson Ports UK...

, Suffolk

Suffolk

Suffolk is a non-metropolitan county of historic origin in East Anglia, England. It has borders with Norfolk to the north, Cambridgeshire to the west and Essex to the south. The North Sea lies to the east...

. Work there resulted in the design and installation of aircraft detection and tracking stations called Chain Home

Chain Home

Chain Home was the codename for the ring of coastal Early Warning radar stations built by the British before and during the Second World War. The system otherwise known as AMES Type 1 consisted of radar fixed on top of a radio tower mast, called a 'station' to provide long-range detection of...

along the East and South coasts of England in time for the outbreak of World War II in 1939. This system provided the vital advance information that helped the Royal Air Force win the Battle of Britain

Battle of Britain

The Battle of Britain is the name given to the World War II air campaign waged by the German Air Force against the United Kingdom during the summer and autumn of 1940...

.

Early years

Born in BrechinBrechin

Brechin is a former royal burgh in Angus, Scotland. Traditionally Brechin is often described as a city because of its cathedral and its status as the seat of a pre-Reformation Roman Catholic diocese , but that status has not been officially recognised in the modern era...

, Angus

Angus

Angus is one of the 32 local government council areas of Scotland, a registration county and a lieutenancy area. The council area borders Aberdeenshire, Perth and Kinross and Dundee City...

, Scotland

Scotland

Scotland is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Occupying the northern third of the island of Great Britain, it shares a border with England to the south and is bounded by the North Sea to the east, the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, and the North Channel and Irish Sea to the...

, Watson-Watt was a descendant of James Watt

James Watt

James Watt, FRS, FRSE was a Scottish inventor and mechanical engineer whose improvements to the Newcomen steam engine were fundamental to the changes brought by the Industrial Revolution in both his native Great Britain and the rest of the world.While working as an instrument maker at the...

, the famous engineer and inventor of the practical steam engine

Steam engine

A steam engine is a heat engine that performs mechanical work using steam as its working fluid.Steam engines are external combustion engines, where the working fluid is separate from the combustion products. Non-combustion heat sources such as solar power, nuclear power or geothermal energy may be...

. After attending Damacre Primary School and Brechin High School

Brechin High School

Brechin High School is a non-denominational secondary school in Brechin, Angus, Scotland.-Admissions:It has approximately 660 students, and a staff of 50...

, he was accepted to University College, Dundee (which was then part of the University of St Andrews

University of St Andrews

The University of St Andrews, informally referred to as "St Andrews", is the oldest university in Scotland and the third oldest in the English-speaking world after Oxford and Cambridge. The university is situated in the town of St Andrews, Fife, on the east coast of Scotland. It was founded between...

but became the University of Dundee

University of Dundee

The University of Dundee is a university based in the city and Royal burgh of Dundee on eastern coast of the central Lowlands of Scotland and with a small number of institutions elsewhere....

in 1967). Watt had a successful time as a student, winning the Carnelley Prize for Chemistry and a class medal for Ordinary Natural Philosophy in 1910.

He graduated with a BSc

Bachelor of Science

A Bachelor of Science is an undergraduate academic degree awarded for completed courses that generally last three to five years .-Australia:In Australia, the BSc is a 3 year degree, offered from 1st year on...

in engineering in 1912, and was offered an assistantship by Professor William Peddie, the holder of the Chair of Physics at University College, Dundee

University of Dundee

The University of Dundee is a university based in the city and Royal burgh of Dundee on eastern coast of the central Lowlands of Scotland and with a small number of institutions elsewhere....

from 1907 to 1942. It was Peddie who encouraged Watson-Watt to study radio, or "wireless telegraphy" as it was then known and who took him through what was effectively a postgraduate class of one on the physics of radio frequency oscillators and wave propagation. At the start of the Great War Watson-Watt was working as an assistant in the College's Engineering Department.

In 1949 a Watson-Watt Chair of Electrical Engineering was established at University College, Dundee

University of Dundee

The University of Dundee is a university based in the city and Royal burgh of Dundee on eastern coast of the central Lowlands of Scotland and with a small number of institutions elsewhere....

.

Early experiments

In 1916 Watson-Watt wanted a job with the War OfficeWar Office

The War Office was a department of the British Government, responsible for the administration of the British Army between the 17th century and 1964, when its functions were transferred to the Ministry of Defence...

, but nothing obvious was available in communications. Instead he joined the Meteorological Office

Met Office

The Met Office , is the United Kingdom's national weather service, and a trading fund of the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills...

, who were interested in his ideas on the use of radio for the detection of thunderstorm

Thunderstorm

A thunderstorm, also known as an electrical storm, a lightning storm, thundershower or simply a storm is a form of weather characterized by the presence of lightning and its acoustic effect on the Earth's atmosphere known as thunder. The meteorologically assigned cloud type associated with the...

s. Lightning

Lightning

Lightning is an atmospheric electrostatic discharge accompanied by thunder, which typically occurs during thunderstorms, and sometimes during volcanic eruptions or dust storms...

gives off a radio signal as it ionizes the air, and he planned on detecting this signal in order to warn pilots of approaching thunderstorms.

His early experiments were successful in detecting the signal, and he quickly proved to be able to do so at long ranges. Two problems remained however. The first was locating the signal, and thus the direction to the storm. This was solved with the use of a directional antenna, which could be manually turned to maximize (or minimize) the signal, thus "pointing" to the storm. Once this was solved the equally difficult problem of actually seeing the fleeting signal became obvious, which he solved with the use of a cathode-ray oscilloscope

Oscilloscope

An oscilloscope is a type of electronic test instrument that allows observation of constantly varying signal voltages, usually as a two-dimensional graph of one or more electrical potential differences using the vertical or 'Y' axis, plotted as a function of time,...

with a long-lasting phosphor

Phosphor

A phosphor, most generally, is a substance that exhibits the phenomenon of luminescence. Somewhat confusingly, this includes both phosphorescent materials, which show a slow decay in brightness , and fluorescent materials, where the emission decay takes place over tens of nanoseconds...

. Such a system represented a significant part of a complete radar system, and was in use as early as 1923. It would, however, need the addition of a pulsed transmitter and a method of measuring the time delay of the received radio echos, and that would in time come from work on ionosonde

Ionosonde

An ionosonde, or chirpsounder, is a special radar for the examination of the ionosphere. An ionosonde consists of:* A high frequency transmitter, automatically tunable over a wide range...

s.

At first he worked at the Wireless Station of Air Ministry Meteorological Office in Aldershot

Aldershot

Aldershot is a town in the English county of Hampshire, located on heathland about southwest of London. The town is administered by Rushmoor Borough Council...

, England

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

. In 1924 when the War Department gave notice that they wished to re-occupy their Aldershot site, he moved to Ditton Park

Ditton Park

Ditton Park was part of the Manor of Ditton which was in what was formerly the south east corner of the English county of Buckinghamshire, before the county boundary reorganisations of 1974 & 1998 which moved it to the Slough Unitary Authority, which is in the ceremonial county of Berkshire.Ditton...

near Slough

Slough

Slough is a borough and unitary authority within the ceremonial county of Royal Berkshire, England. The town straddles the A4 Bath Road and the Great Western Main Line, west of central London...

in Berkshire

Berkshire

Berkshire is a historic county in the South of England. It is also often referred to as the Royal County of Berkshire because of the presence of the royal residence of Windsor Castle in the county; this usage, which dates to the 19th century at least, was recognised by the Queen in 1957, and...

. The National Physical Laboratory

National Physical Laboratory, UK

The National Physical Laboratory is the national measurement standards laboratory for the United Kingdom, based at Bushy Park in Teddington, London, England. It is the largest applied physics organisation in the UK.-Description:...

(NPL) already had a research station there. In 1927 they were amalgamated as the Radio Research Station

Radio Research Station

The Radio Research Station 1924 - August 31, 1979 at Ditton Park, Buckinghamshire, England was the UK government research laboratory which pioneered the regular observation of the ionosphere by ionosondes in continuous operation since September 20, 1932, and applied the ionosonde technology for the...

, with Watson-Watt in charge. After a further re-organisation in 1933, Watson-Watt became Superintendent of the Radio Department of NPL in Teddington

Teddington

Teddington is a suburban area in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames in south west London, on the north bank of the River Thames, between Hampton Wick and Twickenham. It stretches inland from the River Thames to Bushy Park...

.

The air defence problem

In 1934, the Air Ministry set up a committee chaired by Sir Henry TizardHenry Tizard

Sir Henry Thomas Tizard FRS was an English chemist and inventor and past Rector of Imperial College....

to advance the state of the art of air defence in the UK. During World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

, the Germans had used Zeppelin

Zeppelin

A Zeppelin is a type of rigid airship pioneered by the German Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin in the early 20th century. It was based on designs he had outlined in 1874 and detailed in 1893. His plans were reviewed by committee in 1894 and patented in the United States on 14 March 1899...

s as long-range bombers over London and other cities and defences had struggled to counter the threat. Since that time aircraft capabilities had improved considerably, and existing weapons were unlikely to have any effect on a raid.

The prospect of aerial bombardment of civilian areas was causing the government anxiety with heavy bombers able to approach from altitudes that anti-aircraft guns of the day were unable to reach. With the enemy airfields only 20 minutes away, the bombers would have dropped their bombs and be returning to base before the intercepting fighters could get to altitude. The only solution would be to have standing patrols of fighters in the air at all times, but with the limited cruising time of a fighter this would require a gigantic standing force. A plausible solution was urgently needed.

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

was rumored to have a "death-ray

Death ray

The death ray or death beam was a theoretical particle beam or electromagnetic weapon of the 1920s through the 1930s that was claimed to have been invented independently by Nikola Tesla, Edwin R. Scott, Harry Grindell Matthews, and Graichen, as well as others...

" using radio waves that was capable of destroying towns, cities and people. In January 1935, H.E. Wimperis, Director of Scientific Research at the Air Ministry, asked Watson-Watt about the possibly of building their version of a death-ray, specifically to be used against aircraft. Watson-Watt quickly returned a calculation carried out by his assistant, Arnold Wilkins

Arnold Frederic Wilkins

Arnold Frederic Wilkins O.B.E., was a pioneer in developing the use of radar.-Early life:...

, showing that the device was impossible to construct, and fears of a Nazi version soon vanished. However he also mentioned in the same report: "Meanwhile attention is being turned to the still difficult, but less unpromising, problem of radio detection and numerical considerations on the method of detection by reflected radio waves will be submitted when required."

Aircraft detection and location

Air Ministry

The Air Ministry was a department of the British Government with the responsibility of managing the affairs of the Royal Air Force, that existed from 1918 to 1964...

, entitled Detection and location of aircraft by radio methods. Although not as exciting as a death-ray, the concept clearly had potential but the Air Ministry, before giving funding, asked for a demonstration proving that radio waves could be reflected by an aircraft. This was ready by 26 February and consisted of two receiving antennas located about ten km away from one of the BBC

BBC

The British Broadcasting Corporation is a British public service broadcaster. Its headquarters is at Broadcasting House in the City of Westminster, London. It is the largest broadcaster in the world, with about 23,000 staff...

's shortwave broadcast stations at Daventry

Daventry

Daventry is a market town in Northamptonshire, England, with a population of 22,367 .-Geography:The town is also the administrative centre of the larger Daventry district, which has a population of 71,838. The town is 77 miles north-northwest of London, 13.9 miles west of Northampton and 10.2...

. The two antennas were phased such that signals travelling directly from the station cancelled themselves out, but signals arriving from other angles were admitted, thereby deflecting the trace on a CRT

Cathode ray tube

The cathode ray tube is a vacuum tube containing an electron gun and a fluorescent screen used to view images. It has a means to accelerate and deflect the electron beam onto the fluorescent screen to create the images. The image may represent electrical waveforms , pictures , radar targets and...

indicator (passive radar

Passive radar

Passive radar systems encompass a class of radar systems that detect and track objects by processing reflections from non-cooperative sources of illumination in the environment, such as commercial broadcast and communications signals...

). Such was the secrecy of this test that only three people witnessed it: Watson-Watt, his assistant Arnold Wilkins, and a single member of the committee, A.P. Rowe. The demonstration was a success; on several occasions a clear signal was seen from a Handley Page Heyford

Handley Page Heyford

The Handley Page Heyford was a twin-engine British biplane bomber of the 1930s. Although it had a short service life, it equipped several squadrons of the RAF as one of the most important British bombers of the mid-1930s, and was the last biplane heavy bomber to serve with the RAF.-Design and...

bomber being flown around the site. Most importantly, the prime minister, Stanley Baldwin

Stanley Baldwin

Stanley Baldwin, 1st Earl Baldwin of Bewdley, KG, PC was a British Conservative politician, who dominated the government in his country between the two world wars...

, was kept quietly informed of radar's progress. On 2 April 1935, Watson-Watt received a patent on a radio device for detecting and locating an aircraft.

In mid-May 1935, Wilkins left the Radio Research Station with a small party, including Edward George Bowen

Edward George Bowen

Edward George 'Taffy' Bowen, CBE, FRS was a British physicist who made a major contribution to the development of radar, and so helped win both the Battle of Britain and the Battle of the Atlantic...

, to start further research at Orford Ness

Orford Ness

Orford Ness is a cuspate foreland shingle spit on the Suffolk coast in Great Britain, linked to the mainland at Aldeburgh and stretching along the coast to Orford and down to North Wier Point, opposite Shingle Street. It is divided from the mainland by the River Alde, and was formed by longshore...

, an isolated peninsula on the coast of the North Sea. By June they were detecting aircraft at 27 km, which was enough for scientists and engineers to stop all work on competing sound-based detection systems

Acoustic location

Acoustic location is the science of using sound to determine the distance and direction of something. Location can be done actively or passively, and can take place in gases , liquids , and in solids .* Active acoustic location involves the creation of sound in order to produce an echo, which is...

. By the end of the year the range was up to 100 km, at which point plans were made in December to set up five stations covering the approaches to London.

One of these stations was to be located on the coast near Orford Ness, and Bawdsey Manor

Bawdsey Manor

Bawdsey Manor stands at a prominent position at the mouth of the River Deben close to the village of Bawdsey in Suffolk, England, about 118 km northeast of London....

was selected to become the main centre for all radar research. In an effort to put a radar defense in place as quickly as possible, Watson-Watt and his team created devices using existing available components, rather than creating new components for the project, and the team did not take additional time to refine and improve the devices. So long as the prototype radars were in workable condition they were put into production. They soon conducted "full scale" tests of a fixed radar radio tower

Radio masts and towers

Radio masts and towers are, typically, tall structures designed to support antennas for telecommunications and broadcasting, including television. They are among the tallest man-made structures...

system that would soon be known as Chain Home

Chain Home

Chain Home was the codename for the ring of coastal Early Warning radar stations built by the British before and during the Second World War. The system otherwise known as AMES Type 1 consisted of radar fixed on top of a radio tower mast, called a 'station' to provide long-range detection of...

, an early detection system that attempted to detect an incoming bomber by radio signals. The tests were a complete failure, with the fighter only seeing the bomber after it had passed its target. The problem was not the radar, but the flow of information from trackers from the Observer Corps to the fighters, which took many steps and was very slow. Henry Tizard

Henry Tizard

Sir Henry Thomas Tizard FRS was an English chemist and inventor and past Rector of Imperial College....

with Patrick Blackett and Hugh Dowding immediately set to work on this problem, designing a 'command and control air defence reporting system' with several layers of reporting that were eventually sent to a single large room for mapping. Observers watching the maps would then tell the fighter groups what to do via direct communications.

By 1937 the first three stations were ready and the associated system was put to the test. The results were encouraging and an immediate order by the government to commission an additional 17 stations was given, resulting in a chain of fixed radar towers along the east and south coast of England. By the start of World War II, 19 were ready to play a key part in the Battle of Britain

Battle of Britain

The Battle of Britain is the name given to the World War II air campaign waged by the German Air Force against the United Kingdom during the summer and autumn of 1940...

, and by the end of the war over 50 had been built. The Germans were aware of the construction of Chain Home but were not sure of its purpose. They tested their theories with a flight of the Zeppelin

Zeppelin

A Zeppelin is a type of rigid airship pioneered by the German Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin in the early 20th century. It was based on designs he had outlined in 1874 and detailed in 1893. His plans were reviewed by committee in 1894 and patented in the United States on 14 March 1899...

LZ 130

LZ 130 Graf Zeppelin

The Graf Zeppelin II was the last of the great German rigid airships built by the Zeppelin Luftschiffbau during the period between the World Wars, the second and final ship of the Hindenburg class named in honor of Paul von Hindenburg...

, but concluded the stations were a new long-range naval communications system.

As early as 1936, it was realized that the Luftwaffe

Luftwaffe

Luftwaffe is a generic German term for an air force. It is also the official name for two of the four historic German air forces, the Wehrmacht air arm founded in 1935 and disbanded in 1946; and the current Bundeswehr air arm founded in 1956....

would turn to night bombing if the day campaign did not go well, and Watson-Watt had put another of the staff from the Radio Research Station, Edward Bowen, in charge of developing a radar that could be carried by a fighter. Night time visual detection of a bomber was good to about 300 m, and the existing Chain Home systems simply didn't have the accuracy needed to get the fighters that close. Bowen decided that an airborne radar should not exceed 90 kg

Kilogram

The kilogram or kilogramme , also known as the kilo, is the base unit of mass in the International System of Units and is defined as being equal to the mass of the International Prototype Kilogram , which is almost exactly equal to the mass of one liter of water...

(200 lb

Pound (mass)

The pound or pound-mass is a unit of mass used in the Imperial, United States customary and other systems of measurement...

in weight, 8 ft³ (230 L

Litre

pic|200px|right|thumb|One litre is equivalent to this cubeEach side is 10 cm1 litre water = 1 kilogram water The litre is a metric system unit of volume equal to 1 cubic decimetre , to 1,000 cubic centimetres , and to 1/1,000 cubic metre...

) in volume, and require no more than 500 watts of power. To reduce the drag of the antennas the operating wavelength could not be much greater than one m, difficult for the day's electronics. "AI" - Airborne Interception, was perfected by 1940, and was instrumental in eventually ending the Blitz

The Blitz

The Blitz was the sustained strategic bombing of Britain by Nazi Germany between 7 September 1940 and 10 May 1941, during the Second World War. The city of London was bombed by the Luftwaffe for 76 consecutive nights and many towns and cities across the country followed...

of 1941. Bowen also fitted airborne radar to maritime patrol aircraft (known in this application as "ASV" - Air to Surface Vessel) and this eventually reduced the threat from submarines.

Contribution to World War II

A. J. P. Taylor

Alan John Percivale Taylor, FBA was a British historian of the 20th century and renowned academic who became well known to millions through his popular television lectures.-Early life:...

paid the highest of praise to Watson-Watt, Sir Henry Tizard

Henry Tizard

Sir Henry Thomas Tizard FRS was an English chemist and inventor and past Rector of Imperial College....

and their associates who developed and put in place radar, crediting them with being fundamental to victory in World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

.

In July 1938 Watson-Watt left Bawdsey Manor and took up the post of Director of Communications Development (DCD-RAE). In 1939 Sir George Lee took over the job of DCD, and Watson-Watt became Scientific Advisor on Telecommunications (SAT) to the Air Ministry

Air Ministry

The Air Ministry was a department of the British Government with the responsibility of managing the affairs of the Royal Air Force, that existed from 1918 to 1964...

, travelling to the USA

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

in 1941 in order to advise them on the severe inadequacies of their air defence efforts illustrated by the Pearl Harbor attack. His contributions to the war effort were so significant that he was knighted in 1942.

Ten years after his knighthood, Watson-Watt was awarded £50,000 by the British government for his contributions in the development of radar. He established a practice as a consulting engineer. In the 1950s moved to Canada

Canada

Canada is a North American country consisting of ten provinces and three territories. Located in the northern part of the continent, it extends from the Atlantic Ocean in the east to the Pacific Ocean in the west, and northward into the Arctic Ocean...

. Later he lived in the USA, where he published Three Steps to Victory in 1958. Around 1958 he appeared as a mystery challenger on the American

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

television programme To Tell The Truth

To Tell the Truth

To Tell the Truth is an American television panel game show created by Bob Stewart and produced by Goodson-Todman Productions that has aired in various forms since 1956 both on networks and in syndication...

.

On one occasion, late in life, Watson-Watt reportedly was pulled over in Canada for speeding by a radar-gun toting policeman. His remark was, "Had I known what you were going to do with it I would never have invented it!" He wrote an ironic poem ("Rough Justice") afterwards:

Pity Sir Robert Watson-Watt,

- strange target of this radar plot

And thus, with others I can mention,

- the victim of his own invention.

His magical all-seeing eye

- enabled cloud-bound planes to fly

but now by some ironic twist

- it spots the speeding motorist

and bites, no doubt with legal wit,

- the hand that once created it.

Marriages

Watson-Watt was married on 20 July 1916 in Hammersmith, London to Margaret Robertson, the daughter of a draughtsman; they later divorced and he re-married in 1952 in Canada. His second wife was Jean Wilkinson, who died in 1964. Two years later, Watson-Watt married Jane Trefusis, former head of the WAAF.He returned to Scotland in the 1960s. In 1966, at the age of 72, he proposed to Dame Katherine Trefusis Forbes, who was 67 years old at the time and had also played a significant role in the Battle of Britain

Battle of Britain

The Battle of Britain is the name given to the World War II air campaign waged by the German Air Force against the United Kingdom during the summer and autumn of 1940...

as the founding Air Commander of the Womens Auxiliary Air Force, which supplied the radar-room operatives. They lived together in London in the winter, and at "The Observatory" – Trefusis Forbes' summer home in Pitlochry

Pitlochry

Pitlochry , is a burgh in the council area of Perth and Kinross, Scotland, lying on the River Tummel. Its population according to the 2001 census was 2,564....

, Perthshire

Perthshire

Perthshire, officially the County of Perth , is a registration county in central Scotland. It extends from Strathmore in the east, to the Pass of Drumochter in the north, Rannoch Moor and Ben Lui in the west, and Aberfoyle in the south...

, during the warmer months. They remained together until her death in 1971. Watson-Watt died in 1973, aged 81, in Inverness

Inverness

Inverness is a city in the Scottish Highlands. It is the administrative centre for the Highland council area, and is regarded as the capital of the Highlands of Scotland...

. Both are buried in the church yard of the Episcopal Church of the Holy Trinity at Pitlochry.

Sources

- Lem, Elizabeth, The Ditton Park Archive

- Sir Robert Watson-Watt bio

- The Royal Air Force Air Defence Radar Museum at RRH Neatishead, Norfolk

- The Watson-Watt Society of Brechin, Angus, Scotland

External links

- Deflating British Radar Myths of World War II A comparison of contemporary British and German radar inventions and their use

- Radar Development In England

- Sir Robert Alexander Watson-Watt's biography

- German Particle Beam Weapon Facility (Tesla Death Ray)