Reconquista (Spanish America)

Encyclopedia

In colonial Spanish America

, the Reconquista refers to the period following the defeat of Napoleon

in 1814 during which royalist armies were able to gain the upper hand in the Spanish American wars of independence. The term makes an analogy to the medieval Reconquista

, in which Christian forces retook the Iberian Peninsula.

During Napoleon's invasion of the Iberian peninsula

, a number of Spanish colonies

in the Americas

moved for greater autonomy or outright independence due to the political instability in Spain. By 1815 the general outlines of which areas were controlled by royalists and pro-independence forces had been established and a general stalemate set in the war. With the exception of rural areas controlled by guerrillas, North America was under the control of royalists, and in South America only the Southern Cone

and New Granada

remained outside of royalist control. After French forces left Spain in 1814, the restored Spanish king, Ferdinand VII, declared the developments in the Americas illegal and sent armies to quell the areas still in rebellion. The impact of these expeditions were most notably felt in Chile

, New Granada, and Venezuela

. The restoration was short lived, reversed by 1820 in these three countries.

, the Cortes in Spain

and several of the congresses in the Americas, and many of the constitutions and new legal codes—had been done in his name. Once in Spain he realized that he had significant support from conservatives

in the general population and the hierarchy of the Spanish Catholic Church, and so on May 4, he repudiated the Spanish Constitution of 1812

and ordered the arrest of liberal leaders who had created it on May 10. Ferdinand justified his actions by stating that the Constitution and other changes had been made by a Cortes

assembled in his absence and without his consent. He also declared all of the juntas and constitutions written in Spanish America invalid and restored the former law codes and political institutions. News of the events arrived through Spanish America during the next three weeks to nine months, depending on time it took goods and people to travel from Spain.

This, in effect, constituted a definitive break with two groups that could have been allies of Ferdinand VII: the autonomous governments, which had not yet declared formal independence, and Spanish liberals who had created a representative government that would fully include the overseas possessions and was seen as an alternative to independence by many in New Spain, Central America

, the Caribbean, Quito (today Ecuador

), Peru

, Upper Peru

(today, Bolivia

) and Chile. Most Spanish Americans were moderates who decided to wait and see what would come out of the restoration of normalcy. Spanish Americans in royalist areas who were committed to independence had already joined guerrilla movements. Ferdinand's actions did set areas outside of the control of the royalist armies on the path to full independence. The governments of these regions, which had their origins in the juntas of 1810—and even moderates there who had entertained a reconciliation with the crown—now saw the need to separate from Spain, if they were to protect the reforms they had enacted.

. Although this force was crucial in retaking a solidly pro-independence region like New Granada, its soldiers were eventually spread out throughout Venezuela, New Granada, Quito and Peru and lost to tropical diseases, diluting their impact on the war. Ultimately, the majority of the royalist forces were composed, not of soldiers sent from Spain, but of Spanish Americans.

on February 17, 1815, the force initially landed at the island of Margarita

in April, where no resistance was encountered. After leaving the island, Morillo's troops reinforced existing royalist forces in the Venezuelan mainland, entering Cumaná

and Caracas

in May. A small part of the main corps set off towards Panamá

, while the main contingent was directed towards the Neogranadine coastal city of Santa Marta

which was still in royalist hands.

After picking up supplies and militia volunteers in Santa Marta

on July 23, the Spanish expeditionary forces besieged Cartagena

. After a five-month siege

the fortified city fell on December 1815. By May 6, 1816, the combined efforts of Spanish and colonial forces, marching south from Cartagena and north from royalist strongholds in Quito

, Pasto

, and Popayán

, completed the reconquest of New Granada, taking Bogotá

. A permanent council of war was set up to judge those accused of treason and rebellion, resulting in the execution of more than a hundred notable republican officials, including Jorge Tadeo Lozano

, Francisco José de Caldas

and José María Cabal. Units of the republican armies of New Granada were incorporated into the royalist army and sent to Peru.

, a royalist bastion in Chile under the command of Brigadier Mariano Osorio

, who was also the newly appointed governor. Osorio succeeded in organizing local recruits into a mobile army of some 5,000 men, of which the troops of the Talaveras Regiment were practically the only Spaniards. The new royalist force fought the patriot forces on October 1 in Rancagua, in which the patriots unsuccessfully tried to stop the expeditionaries from taking Santiago

.

After royalist forces took Santiago

, patriots found in the city—among whom were members of the First Junta

—were exiled to the Juan Fernández Islands

. By November Spanish control had been reestablished in most of Chile. A member of the Talavera Regiment, Vicente San Bruno

was put in charge of carrying out the orders to arrest civilians suspected of having helped or sympathised with the patriots. In 1816 Francisco Marcó del Pont became the new governor and he initiated a new campaign of fierce political and military persecution. Marcó del Pont appointed San Bruno president of a Tribunal of Vigilance and Public Security.

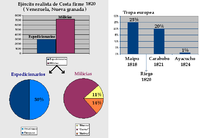

was substituted by a Spanish American soldier, over time, there were more and more Spanish American soldiers in the expeditionary units. For example Pablo Morillo

, commander in chief of the expeditionary force sent South America, reported that he only had 2,000 European soldiers under his command in 1820, in other words, only half of the soldiers of his expeditionary force were European. It is estimated that in the Battle of Maipú

only a quarter of the royalist forces were European soldiers, in the Battle of Carabobo

about a fifth, and in the Battle of Ayacucho

less than 1% was European.

The American militias reflected the racial make-up of the local population. For example, in 1820 the royalist army in Venezuela had 843 white (español), 5,378 Casta

and 980 Indigenous

soldiers.

, where they were well received. Others fled to the Llanos

, where they were out of reach of Morillo's forces. Haitian president Alexandre Pétion

gave the exiles military and monetary aid, which allowed them to resume the struggle for independence in conjunction with the patriots who had organized the Llanero

s into guerrilla bands

. Chilean patriots who escaped the royalist reprisals fled to Mendoza

, an Argentine Andean province under patriot control, where they reorganized themselves under José de San Martín

and Bernardo O'Higgins

. While they prepared to invade Chile, San Martín and O'Higgins initiated a guerrilla campaign under Manuel Rodríguez to keep the royalist forces off balance. Both of these sets of exiles from northern and southern South America formed the basis of what would become the armies that successfully established republics in all of the regions of the continent controlled by the Spanish.

Towards the end of this period the pro-independence forces made two important advances that ultimately led to the continental-wide pincer movement

from southern and northern South America that liberated most of the Spanish American nations on that continent by 1825. In the Southern Cone, San Martín as the governor of Cuyo

, had been organizing an army as early as 1814 in preparation for an invasion of Chile. This became the nucleus of the Army of the Andes

, which received crucial political and material support in 1816 when Juan Martín de Pueyrredón

became Supreme Director

of the United Provinces

. From January to February 1817, San Martín led the Army over the Andes in an audacious move that turned the tables on the royalists in Chile. By February 10, San Martín had control of northern and central Chile, and a year later had control of the south. Chile was secured from royalist control and independence was declared in 1818. San Martín and his allies spent the next two years planning an invasion of Peru, which began in 1820.

In northern South America, Simón Bolívar

devised a similar plan to liberate New Granada from the royalists. Like San Martín, Bolívar personally undertook the efforts to create an army to invade a neighboring country and collaborated with pro-independence exiles from that region. Unlike San Martín, Bolívar did not have the approval of the Venezuelan congress

. From June to July 1819, using the rainy season

as cover, Bolívar led an army composed mostly of Llaneros over the cold, forbidding passes of the Andes, but the gamble paid off. By August Bolívar was in control of Bogotá

and gained the support of New Granada, which still resented the harsh reconquest carried out under Morillo. With the resources of New Granada, Bolívar became the undisputed leader of the patriots in Venezuela and orchestrated the union of the two regions in a new state, Gran Colombia

.

Hispanic America

Hispanic America or Spanish America is the region comprising the American countries inhabited by Spanish-speaking populations.These countries have significant commonalities with each other and with Spain, whose colonies they formerly were...

, the Reconquista refers to the period following the defeat of Napoleon

Napoleon I of France

Napoleon Bonaparte was a French military and political leader during the latter stages of the French Revolution.As Napoleon I, he was Emperor of the French from 1804 to 1815...

in 1814 during which royalist armies were able to gain the upper hand in the Spanish American wars of independence. The term makes an analogy to the medieval Reconquista

Reconquista

The Reconquista was a period of almost 800 years in the Middle Ages during which several Christian kingdoms succeeded in retaking the Muslim-controlled areas of the Iberian Peninsula broadly known as Al-Andalus...

, in which Christian forces retook the Iberian Peninsula.

During Napoleon's invasion of the Iberian peninsula

Peninsular War

The Peninsular War was a war between France and the allied powers of Spain, the United Kingdom, and Portugal for control of the Iberian Peninsula during the Napoleonic Wars. The war began when French and Spanish armies crossed Spain and invaded Portugal in 1807. Then, in 1808, France turned on its...

, a number of Spanish colonies

Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire comprised territories and colonies administered directly by Spain in Europe, in America, Africa, Asia and Oceania. It originated during the Age of Exploration and was therefore one of the first global empires. At the time of Habsburgs, Spain reached the peak of its world power....

in the Americas

Americas

The Americas, or America , are lands in the Western hemisphere, also known as the New World. In English, the plural form the Americas is often used to refer to the landmasses of North America and South America with their associated islands and regions, while the singular form America is primarily...

moved for greater autonomy or outright independence due to the political instability in Spain. By 1815 the general outlines of which areas were controlled by royalists and pro-independence forces had been established and a general stalemate set in the war. With the exception of rural areas controlled by guerrillas, North America was under the control of royalists, and in South America only the Southern Cone

Southern Cone

Southern Cone is a geographic region composed of the southernmost areas of South America, south of the Tropic of Capricorn. Although geographically this includes part of Southern and Southeast of Brazil, in terms of political geography the Southern cone has traditionally comprised Argentina,...

and New Granada

New Kingdom of Granada

The New Kingdom of Granada was the name given to a group of 16th century Spanish colonial provinces in northern South America governed by the president of the Audiencia of Bogotá, an area corresponding mainly to modern day Colombia and parts of Venezuela. Originally part of the Viceroyalty of...

remained outside of royalist control. After French forces left Spain in 1814, the restored Spanish king, Ferdinand VII, declared the developments in the Americas illegal and sent armies to quell the areas still in rebellion. The impact of these expeditions were most notably felt in Chile

Chile

Chile ,officially the Republic of Chile , is a country in South America occupying a long, narrow coastal strip between the Andes mountains to the east and the Pacific Ocean to the west. It borders Peru to the north, Bolivia to the northeast, Argentina to the east, and the Drake Passage in the far...

, New Granada, and Venezuela

Venezuela

Venezuela , officially called the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela , is a tropical country on the northern coast of South America. It borders Colombia to the west, Guyana to the east, and Brazil to the south...

. The restoration was short lived, reversed by 1820 in these three countries.

Restoration of Ferdinand VII

The restoration of Ferdinand VII signified an important change, since most of the political and legal changes done on both sides of the Atlantic—the myriad of juntasJunta (Peninsular War)

In the Napoleonic era, junta was the name chosen by several local administrations formed in Spain during the Peninsular War as a patriotic alternative to the official administration toppled by the French invaders...

, the Cortes in Spain

Cádiz Cortes

The Cádiz Cortes were sessions of the national legislative body which met in the safe haven of Cádiz during the French occupation of Spain during the Napoleonic Wars...

and several of the congresses in the Americas, and many of the constitutions and new legal codes—had been done in his name. Once in Spain he realized that he had significant support from conservatives

Conservatism

Conservatism is a political and social philosophy that promotes the maintenance of traditional institutions and supports, at the most, minimal and gradual change in society. Some conservatives seek to preserve things as they are, emphasizing stability and continuity, while others oppose modernism...

in the general population and the hierarchy of the Spanish Catholic Church, and so on May 4, he repudiated the Spanish Constitution of 1812

Spanish Constitution of 1812

The Spanish Constitution of 1812 was promulgated 19 March 1812 by the Cádiz Cortes, the national legislative assembly of Spain, while in refuge from the Peninsular War...

and ordered the arrest of liberal leaders who had created it on May 10. Ferdinand justified his actions by stating that the Constitution and other changes had been made by a Cortes

Cádiz Cortes

The Cádiz Cortes were sessions of the national legislative body which met in the safe haven of Cádiz during the French occupation of Spain during the Napoleonic Wars...

assembled in his absence and without his consent. He also declared all of the juntas and constitutions written in Spanish America invalid and restored the former law codes and political institutions. News of the events arrived through Spanish America during the next three weeks to nine months, depending on time it took goods and people to travel from Spain.

This, in effect, constituted a definitive break with two groups that could have been allies of Ferdinand VII: the autonomous governments, which had not yet declared formal independence, and Spanish liberals who had created a representative government that would fully include the overseas possessions and was seen as an alternative to independence by many in New Spain, Central America

Central America

Central America is the central geographic region of the Americas. It is the southernmost, isthmian portion of the North American continent, which connects with South America on the southeast. When considered part of the unified continental model, it is considered a subcontinent...

, the Caribbean, Quito (today Ecuador

Ecuador

Ecuador , officially the Republic of Ecuador is a representative democratic republic in South America, bordered by Colombia on the north, Peru on the east and south, and by the Pacific Ocean to the west. It is one of only two countries in South America, along with Chile, that do not have a border...

), Peru

Peru

Peru , officially the Republic of Peru , is a country in western South America. It is bordered on the north by Ecuador and Colombia, on the east by Brazil, on the southeast by Bolivia, on the south by Chile, and on the west by the Pacific Ocean....

, Upper Peru

Upper Peru

Upper Peru was the region in the Viceroyalty of Peru, and after 1776, the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata, comprising the governorships of Potosí, La Paz, Cochabamba, Los Chiquitos, Moxos and Charcas...

(today, Bolivia

Bolivia

Bolivia officially known as Plurinational State of Bolivia , is a landlocked country in central South America. It is the poorest country in South America...

) and Chile. Most Spanish Americans were moderates who decided to wait and see what would come out of the restoration of normalcy. Spanish Americans in royalist areas who were committed to independence had already joined guerrilla movements. Ferdinand's actions did set areas outside of the control of the royalist armies on the path to full independence. The governments of these regions, which had their origins in the juntas of 1810—and even moderates there who had entertained a reconciliation with the crown—now saw the need to separate from Spain, if they were to protect the reforms they had enacted.

Expeditionary campaigns

During this period royalist forces made advances into New Granada, which they controlled from 1815 to 1819, and into Chile, from 1814 to 1817. Except for royalist areas in the northeast and south, the provinces of New Granada had maintained independence from Spain since 1810, unlike neighboring Venezuela, where royalists and pro-independence forces had exchanged control of the country several times. To pacify Venezuela and to retake New Granada, Spain organized and sent in 1815 the largest armed force it ever sent to the New World, consisting of approximately 10,000 troops and nearly sixty ships under the command of Pablo MorilloPablo Morillo

Pablo Morillo y Morillo, Count of Cartagena and Marquess of La Puerta, aka El Pacificador was a Spanish general....

. Although this force was crucial in retaking a solidly pro-independence region like New Granada, its soldiers were eventually spread out throughout Venezuela, New Granada, Quito and Peru and lost to tropical diseases, diluting their impact on the war. Ultimately, the majority of the royalist forces were composed, not of soldiers sent from Spain, but of Spanish Americans.

The expeditionary army of Tierra Firme

Leaving the port of CádizCádiz

Cadiz is a city and port in southwestern Spain. It is the capital of the homonymous province, one of eight which make up the autonomous community of Andalusia....

on February 17, 1815, the force initially landed at the island of Margarita

Isla Margarita

Margarita Island is the largest island of the state of Nueva Esparta in Venezuela, situated in the Caribbean Sea, off the northeastern coast of the country. The state also contains two other smaller islands: Coche and Cubagua. The capital city of Nueva Esparta is La Asunción, located in a river...

in April, where no resistance was encountered. After leaving the island, Morillo's troops reinforced existing royalist forces in the Venezuelan mainland, entering Cumaná

Cumaná

Cumaná is the capital of Venezuela's Sucre State. It is located 402 km east of Caracas. It was the first settlement founded by Europeans in the mainland America, in 1501 by Franciscan friars, but due to successful attacks by the indigenous people, it had to be refounded several times...

and Caracas

Caracas

Caracas , officially Santiago de León de Caracas, is the capital and largest city of Venezuela; natives or residents are known as Caraquenians in English . It is located in the northern part of the country, following the contours of the narrow Caracas Valley on the Venezuelan coastal mountain range...

in May. A small part of the main corps set off towards Panamá

Panama

Panama , officially the Republic of Panama , is the southernmost country of Central America. Situated on the isthmus connecting North and South America, it is bordered by Costa Rica to the northwest, Colombia to the southeast, the Caribbean Sea to the north and the Pacific Ocean to the south. The...

, while the main contingent was directed towards the Neogranadine coastal city of Santa Marta

Santa Marta

Santa Marta is the capital city of the Colombian department of Magdalena in the Caribbean Region. It was founded in July 29, 1525 by the Spanish conqueror Rodrigo de Bastidas, which makes it the oldest remaining city in Colombia...

which was still in royalist hands.

After picking up supplies and militia volunteers in Santa Marta

Santa Marta

Santa Marta is the capital city of the Colombian department of Magdalena in the Caribbean Region. It was founded in July 29, 1525 by the Spanish conqueror Rodrigo de Bastidas, which makes it the oldest remaining city in Colombia...

on July 23, the Spanish expeditionary forces besieged Cartagena

Cartagena, Colombia

Cartagena de Indias , is a large Caribbean beach resort city on the northern coast of Colombia in the Caribbean Coast Region and capital of Bolívar Department...

. After a five-month siege

Siege

A siege is a military blockade of a city or fortress with the intent of conquering by attrition or assault. The term derives from sedere, Latin for "to sit". Generally speaking, siege warfare is a form of constant, low intensity conflict characterized by one party holding a strong, static...

the fortified city fell on December 1815. By May 6, 1816, the combined efforts of Spanish and colonial forces, marching south from Cartagena and north from royalist strongholds in Quito

Quito

San Francisco de Quito, most often called Quito , is the capital city of Ecuador in northwestern South America. It is located in north-central Ecuador in the Guayllabamba river basin, on the eastern slopes of Pichincha, an active stratovolcano in the Andes mountains...

, Pasto

Pasto

Pasto, officially San Juan de Pasto, is the capital of the department of Nariño, located in southwest Colombia. The city is located in the "Atriz Valley", on the Andes cordillera, at the foot of the Galeras volcano, at an altitude of 8,290 feet above sea level...

, and Popayán

Popayán

Popayán is the capital of the Colombian department of Cauca. It is located in southwestern Colombia between Colombia's Western Mountain Range and Central Mountain Range...

, completed the reconquest of New Granada, taking Bogotá

Bogotá

Bogotá, Distrito Capital , from 1991 to 2000 called Santa Fé de Bogotá, is the capital, and largest city, of Colombia. It is also designated by the national constitution as the capital of the department of Cundinamarca, even though the city of Bogotá now comprises an independent Capital district...

. A permanent council of war was set up to judge those accused of treason and rebellion, resulting in the execution of more than a hundred notable republican officials, including Jorge Tadeo Lozano

Jorge Tadeo Lozano

Jorge Tadeo Lozano, Viscount of Pastrana was a Neogranadine scientist, journalist, and politician who presided over the Constituent College of Cundinamarca and was elected President of Cundinamarca in 1811....

, Francisco José de Caldas

Francisco José de Caldas

Francisco José de Caldas was a Colombian lawyer, naturalist, and geographer who died a martyr by orders of Pablo Morillo during the Reconquista for being a precursor of the Independence of New Granada ....

and José María Cabal. Units of the republican armies of New Granada were incorporated into the royalist army and sent to Peru.

The Chilean campaign

In August 1814 the Queen's Talavera Regiment, a unit which had fought in the Peninsular War, arrived in TalcahuanoTalcahuano

Talcahuano is a port city and commune in the Biobío Region of Chile. It is part of the Greater Concepción conurbation. Talcahuano is located in the south of the Central Zone of Chile.-Geography:...

, a royalist bastion in Chile under the command of Brigadier Mariano Osorio

Mariano Osorio

Mariano de Osorio was a Spanish general and Governor of Chile, from 1814 to 1815.-Early career:Osorio was born in Seville, Spain. He joined the Spanish army and as many of his contemporaries, his military career began during the Spanish Peninsular War in 1808 as an artillery general, as well as...

, who was also the newly appointed governor. Osorio succeeded in organizing local recruits into a mobile army of some 5,000 men, of which the troops of the Talaveras Regiment were practically the only Spaniards. The new royalist force fought the patriot forces on October 1 in Rancagua, in which the patriots unsuccessfully tried to stop the expeditionaries from taking Santiago

Santiago, Chile

Santiago , also known as Santiago de Chile, is the capital and largest city of Chile, and the center of its largest conurbation . It is located in the country's central valley, at an elevation of above mean sea level...

.

After royalist forces took Santiago

Santiago, Chile

Santiago , also known as Santiago de Chile, is the capital and largest city of Chile, and the center of its largest conurbation . It is located in the country's central valley, at an elevation of above mean sea level...

, patriots found in the city—among whom were members of the First Junta

Government Junta of Chile (1810)

Government Junta of the Kingdom of Chile , also known as the First Government Junta, was the organ established to rule Chile following the deposition and imprisonment of King Ferdinand VII by Napoleon Bonaparte...

—were exiled to the Juan Fernández Islands

Juan Fernández Islands

The Juan Fernández Islands are a sparsely inhabited island group reliant on tourism and fishing in the South Pacific Ocean, situated about off the coast of Chile, and is composed of three main volcanic islands; Robinson Crusoe Island, Alejandro Selkirk Island and Santa Clara Island, the first...

. By November Spanish control had been reestablished in most of Chile. A member of the Talavera Regiment, Vicente San Bruno

Vicente San Bruno

Vicente San Bruno Rovira was a Spanish military officer, infamous for his cruelty during the Chilean War of Independence.-In Chile:...

was put in charge of carrying out the orders to arrest civilians suspected of having helped or sympathised with the patriots. In 1816 Francisco Marcó del Pont became the new governor and he initiated a new campaign of fierce political and military persecution. Marcó del Pont appointed San Bruno president of a Tribunal of Vigilance and Public Security.

The royalist military

Overall, Europeans formed only about a tenth of the royalist armies in Spanish America, and only about half of the expeditionary units once they were deployed in the Americas. Since each European soldier casualtyCasualty (person)

A casualty is a person who is the victim of an accident, injury, or trauma. The word casualties is most often used by the news media to describe deaths and injuries resulting from wars or disasters...

was substituted by a Spanish American soldier, over time, there were more and more Spanish American soldiers in the expeditionary units. For example Pablo Morillo

Pablo Morillo

Pablo Morillo y Morillo, Count of Cartagena and Marquess of La Puerta, aka El Pacificador was a Spanish general....

, commander in chief of the expeditionary force sent South America, reported that he only had 2,000 European soldiers under his command in 1820, in other words, only half of the soldiers of his expeditionary force were European. It is estimated that in the Battle of Maipú

Battle of Maipú

The Battle of Maipú was a battle fought near Santiago, Chile on April 5, 1818 between South American rebels and Spanish royalists, during the Chilean War of Independence...

only a quarter of the royalist forces were European soldiers, in the Battle of Carabobo

Battle of Carabobo

The Battle of Carabobo, 24 June 1821, was fought between independence fighters, led by Simón Bolívar, and the Royalist forces, led by Spanish Field Marshal Miguel de la Torre. Bolívar's decisive victory at Carabobo led to the independence of Venezuela....

about a fifth, and in the Battle of Ayacucho

Battle of Ayacucho

The Battle of Ayacucho was a decisive military encounter during the Peruvian War of Independence. It was the battle that sealed the independence of Peru, as well as the victory that ensured independence for the rest of South America...

less than 1% was European.

The American militias reflected the racial make-up of the local population. For example, in 1820 the royalist army in Venezuela had 843 white (español), 5,378 Casta

Casta

Casta is a Portuguese and Spanish term used in seventeenth and eighteenth centuries mainly in Spanish America to describe as a whole the mixed-race people which appeared in the post-Conquest period...

and 980 Indigenous

Indigenous peoples of the Americas

The indigenous peoples of the Americas are the pre-Columbian inhabitants of North and South America, their descendants and other ethnic groups who are identified with those peoples. Indigenous peoples are known in Canada as Aboriginal peoples, and in the United States as Native Americans...

soldiers.

Reverses

Far from pacifying the patriots, these actions served to incite them, and soon even moderates, who had previously envisioned a reconciliation with the Spanish crown, concluded that independence was the only way to guarantee their new found freedoms. In New Granada, patriots reacted to the expeditionary force with disunity, aiding Morillo's advance. Several Neogranadine and Venezuelan exiles fled to HaitiHaiti

Haiti , officially the Republic of Haiti , is a Caribbean country. It occupies the western, smaller portion of the island of Hispaniola, in the Greater Antillean archipelago, which it shares with the Dominican Republic. Ayiti was the indigenous Taíno or Amerindian name for the island...

, where they were well received. Others fled to the Llanos

Llanos

The Llanos is a vast tropical grassland plain situated to the east of the Andes in Colombia and Venezuela, in northwestern South America. It is an ecoregion of the Flooded grasslands and savannas Biome....

, where they were out of reach of Morillo's forces. Haitian president Alexandre Pétion

Alexandre Pétion

Alexandre Sabès Pétion was President of the Republic of Haiti from 1806 until his death. He is considered as one of Haiti's founding fathers, together with Toussaint Louverture, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, and his rival Henri Christophe.-Early life:Pétion was born in Port-au-Prince to a Haitian...

gave the exiles military and monetary aid, which allowed them to resume the struggle for independence in conjunction with the patriots who had organized the Llanero

Llanero

A llanero is a Venezuelan or Colombian herder. The name is taken from the Llanos grasslands occupying western Venezuela and eastern Colombia. The Llanero were originally part Spanish and Indian and have a strong culture including a distinctive form of music.During the wars of independence,...

s into guerrilla bands

Guerrilla warfare

Guerrilla warfare is a form of irregular warfare and refers to conflicts in which a small group of combatants including, but not limited to, armed civilians use military tactics, such as ambushes, sabotage, raids, the element of surprise, and extraordinary mobility to harass a larger and...

. Chilean patriots who escaped the royalist reprisals fled to Mendoza

Mendoza Province

The Province of Mendoza is a province of Argentina, located in the western central part of the country in the Cuyo region. It borders to the north with San Juan, the south with La Pampa and Neuquén, the east with San Luis, and to the west with the republic of Chile; the international limit is...

, an Argentine Andean province under patriot control, where they reorganized themselves under José de San Martín

José de San Martín

José Francisco de San Martín, known simply as Don José de San Martín , was an Argentine general and the prime leader of the southern part of South America's successful struggle for independence from Spain.Born in Yapeyú, Corrientes , he left his mother country at the...

and Bernardo O'Higgins

Bernardo O'Higgins

Bernardo O'Higgins Riquelme was a Chilean independence leader who, together with José de San Martín, freed Chile from Spanish rule in the Chilean War of Independence. Although he was the second Supreme Director of Chile , he is considered one of Chile's founding fathers, as he was the first holder...

. While they prepared to invade Chile, San Martín and O'Higgins initiated a guerrilla campaign under Manuel Rodríguez to keep the royalist forces off balance. Both of these sets of exiles from northern and southern South America formed the basis of what would become the armies that successfully established republics in all of the regions of the continent controlled by the Spanish.

Towards the end of this period the pro-independence forces made two important advances that ultimately led to the continental-wide pincer movement

Pincer movement

The pincer movement or double envelopment is a military maneuver. The flanks of the opponent are attacked simultaneously in a pinching motion after the opponent has advanced towards the center of an army which is responding by moving its outside forces to the enemy's flanks, in order to surround it...

from southern and northern South America that liberated most of the Spanish American nations on that continent by 1825. In the Southern Cone, San Martín as the governor of Cuyo

Cuyo (Argentina)

Cuyo is the name given to the wine-producing, mountainous area of central-west Argentina. Historically it comprised the provinces of San Juan, San Luis and Mendoza. The term New Cuyo is a modern one, which indicates both Cuyo proper and the province of La Rioja...

, had been organizing an army as early as 1814 in preparation for an invasion of Chile. This became the nucleus of the Army of the Andes

Army of the Andes

The Army of the Andes was a military force created by the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata and mustered by general José de San Martín in his campaign to free Chile from the Spanish Empire...

, which received crucial political and material support in 1816 when Juan Martín de Pueyrredón

Juan Martín de Pueyrredón

Juan Martín de Pueyrredón y O'Dogan was an Argentine general and politician of the early 19th century. He was appointed Supreme Director of the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata after the Argentine Declaration of Independence.-Early life:Pueyrredón was born in Buenos Aires, the fifth of...

became Supreme Director

Supreme Director of the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata

The Supreme Director of the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata , was a title given to the executive officers of the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata, according to the form of government established in 1814 by the Asamblea del Año XIII...

of the United Provinces

United Provinces of South America

The United Provinces of South America was the original name of the state that emerged from the May Revolution and the early developments of the Argentine War of Independence...

. From January to February 1817, San Martín led the Army over the Andes in an audacious move that turned the tables on the royalists in Chile. By February 10, San Martín had control of northern and central Chile, and a year later had control of the south. Chile was secured from royalist control and independence was declared in 1818. San Martín and his allies spent the next two years planning an invasion of Peru, which began in 1820.

In northern South America, Simón Bolívar

Simón Bolívar

Simón José Antonio de la Santísima Trinidad Bolívar y Palacios Ponte y Yeiter, commonly known as Simón Bolívar was a Venezuelan military and political leader...

devised a similar plan to liberate New Granada from the royalists. Like San Martín, Bolívar personally undertook the efforts to create an army to invade a neighboring country and collaborated with pro-independence exiles from that region. Unlike San Martín, Bolívar did not have the approval of the Venezuelan congress

Congress of Angostura

The Congress of Angostura was summoned by Simón Bolívar and took place in Angostura during the wars of Independence of Colombia and Venezuela. It met from February 15, 1819, to July 31, 1821, when the Congress of Cúcuta began its sessions.It consisted of twenty-six delegates, representing...

. From June to July 1819, using the rainy season

Wet season

The the wet season, or rainy season, is the time of year, covering one or more months, when most of the average annual rainfall in a region occurs. The term green season is also sometimes used as a euphemism by tourist authorities. Areas with wet seasons are dispersed across portions of the...

as cover, Bolívar led an army composed mostly of Llaneros over the cold, forbidding passes of the Andes, but the gamble paid off. By August Bolívar was in control of Bogotá

Bogotá

Bogotá, Distrito Capital , from 1991 to 2000 called Santa Fé de Bogotá, is the capital, and largest city, of Colombia. It is also designated by the national constitution as the capital of the department of Cundinamarca, even though the city of Bogotá now comprises an independent Capital district...

and gained the support of New Granada, which still resented the harsh reconquest carried out under Morillo. With the resources of New Granada, Bolívar became the undisputed leader of the patriots in Venezuela and orchestrated the union of the two regions in a new state, Gran Colombia

Gran Colombia

Gran Colombia is a name used today for the state that encompassed much of northern South America and part of southern Central America from 1819 to 1831. This short-lived republic included the territories of present-day Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Panama, northern Peru and northwest Brazil. The...

.