Otomi language

Encyclopedia

Otomi (ˌoʊtəˈmiː, in Spanish spelling Otomí otoˈmi) is an Oto-Manguean language

and one of the indigenous languages of Mexico, spoken by approximately 240,000 indigenous Otomi people

in the central altiplano

region of Mexico

. The language is spoken in many different dialects, some of which are not mutually intelligible

, therefore it is in effect a dialect continuum

. The word Hñähñu hɲɑ̃hɲṹ has been proposed as an endonym, but since it represents the usage of a single dialect it has not gained wide currency. Linguists have classified the modern dialects into three dialect areas: the Northwestern dialects spoken in Querétaro

, Hidalgo and Guanajuato

; the Southwestern dialects spoken in the State of Mexico

; and the Eastern dialects spoken in the highlands of Veracruz

, Puebla

, and eastern Hidalgo and in villages in Tlaxcala

and Mexico states.

Like all other Oto-Manguean languages, Otomi is a tonal language and most varieties distinguish three tones. Nouns are marked only for possessor; plural number is marked by the definite article and by a verb suffix, and some dialects maintain the historically existing dual number marking. There is no case marking. Verb morphology can be described as either fusional or agglutinating

depending on analysis. In verb inflection, infixation, consonant mutation, and apocope are prominent processes, and the number of irregular verbs is large. The grammatical subject

in a sentence is cross referenced by a class of morpheme

s that can be analysed as either proclitics or prefix

es and which also mark for tense

, aspect

and mood

. Verbs are inflected for either direct object or dative object (but not for both simultaneously) by suffixes. Inclusive 'we' and exclusive 'we' are distinguished (the clusivity

distinction). Otomi syntax generally has nominative–accusative alignment

with some traits of active–stative alignment

.

After the Spanish conquest Otomi became a written language when friars taught the Otomi to write the language using the Latin alphabet

; the written language of the colonial period is often called Classical Otomi

. Several codices

and grammars were composed in Classical Otomi. A negative stereotype of the Otomi promoted by the Nahuas and perpetuated by the Spanish resulted in a loss of status for the Otomi, who began to abandon their language in favor of Spanish. The attitude of the larger world toward the Otomi language began to change in 2003 when Otomi was granted recognition as a national language under Mexican law together with 61 other indigenous languages.

otomitl, which is possibly derived from an older word totomitl "shooter of birds". It is not an Otomi endonym; the Otomi refer to themselves as Hñähñú, Hñähño, Hñotho, Hñähü, Hñätho, Yųhų, Yųhmų, Ñųhų, or Ñañhų depending on which dialect of Otomi they speak.See List of Otomi languages for information about which dialect areas use which terms. Most of the variant forms are composed of two morpheme

s meaning "speak" and "well" respectively.

The word Otomi entered the Spanish language through Nahuatl and is used to describe the larger Otomi macroethnic group and the dialect continuum. From Spanish the word Otomi has become entrenched in the linguistic and anthropological literature. Among linguists, the suggestion has been made to change the academic designation from Otomi to Hñähñú, the endonym used by the Otomi of the Mezquital valley; however, no common endonym exists for all dialects of the language.

branch of the Oto-Manguean languages

. Within Oto-Pamean it is part of the Otomian subgroup which also includes Mazahua, Matlatzinca

and Ocuilteco/Tlahuica

.

, the greatest Mesoamerican ceremonial center of the Classic period, whose demise occurred ca. 600 AD.

The Precolumbian

Otomi people did not have a proper writing system

, but the largely ideographic Aztec writing

could be read in Otomi as well as Nahuatl. The Otomi often translated names of places or rulers into Otomi rather than using the Nahuatl names. For example, the Nahuatl place name Tenochtitlān, "place of Opuntia cactus", was rendered as *ʔmpôndo in proto-Otomi, with the same meaning.In most modern varieties of Otomi the name for "Mexico" has changed to ʔmôndo (in Ixtenco Otomi) or ʔmóndá (in Mezquital Otomi). In some varieties of Highland Otomi it is mbôndo. Only Tilapa Otomi and Acazulco Otomi preserve the original pronunciation (Lastra, Los Otomíes, p. 47).

At the time of the Spanish conquest of central Mexico, Otomi had a much wider distribution than now, with large Otomi speaking areas existing in the modern states of Jalisco

At the time of the Spanish conquest of central Mexico, Otomi had a much wider distribution than now, with large Otomi speaking areas existing in the modern states of Jalisco

and Michoacan

. After the conquest, the Otomi people experienced a period of geographical expansion as the Spaniards employed Otomi warriors in their expeditions of conquest into northern Mexico. During and after the Mixtón rebellion

, in which Otomi warriors fought for the Spanish, Otomis settled areas in Querétaro (where they founded the city of Querétaro) and Guanajuato which previously had been inhabited by nomadic Chichimecs. Because Spanish colonial historians such as Bernardino de Sahagún

used primarily Nahua speakers as sources for their histories of the colony, the Nahuas' negative image of the Otomi people was perpetuated throughout the colonial period, which contributed to the Otomi gradually abandoning their language.

"Classical Otomi

" is the term used to define the Otomi spoken in the early centuries of colonial rule. This historical stage of the language was given Latin orthography and documented by Spanish friars who learned it in order to proselytize the Otomi peoples. Text in Classical Otomi is not readily comprehensible, since the Spanish speaking friars failed to differentiate the varied vowel and consonant sounds of the Otomi language. Friars and monks from the Spanish mendicant orders such as the Franciscans wrote Otomi grammars, the earliest of which is that of Friar Pedro de Cárceres' Arte de la lengua othomí [sic], written perhaps as early as 1580, but not published until 1907 In 1605, Alonso de Urbano wrote a trilingual Spanish-Nahuatl

-Otomi dictionary, which also included a small set of grammatical notes about Otomi. The grammarian of Nahuatl, Horacio Carochi

is known to have written a grammar of Otomi, but no copies have survived. In the latter half of the eighteenth century, an anonymous Jesuit friar wrote the grammar Luces del Otomi, and Neve y Molina wrote a dictionary and a grammar.

During the colonial period, many Otomis were taught to read and write their language. In consequence, a significant number of documents in Otomi exist from the period, both secular and religious, the most well-known of which are the Codices of Huichapan and Jilotepec.

After the colonial period ended in 1813, the Otomi were no longer recognized as an indigenous group, the Otomi language lost its status as a language of education, and the period of Classical Otomi as a literary language ended.

considers Otomi to be a cover term for nine separate Otomi languages and assigns a different ISO code to each of these nine varieties. Other linguists however, consider Otomi to be the best name for a dialect continuum

that is clearly demarcated from its closest relative, Mazahua

. For the purposes of this article, the latter approach will be followed.

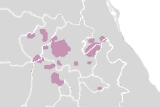

Currently Otomi dialects are spoken collectively by circa 239,000 speakers—some 5 to 6 percent of whom are monolingual—in widely scattered districts (see map). The highest concentration of speakers is found in the Valle de Mezquital region of Hidalgo and in the southern portion of Querétaro

, where some municipalities have concentrations of Otomi speakers as high as 60–70%. Because of recent migratory patterns, small populations of Otomi speakers can be found in new locations throughout Mexico and in the United States.

Dialectal diversity in Otomi is so great that some dialects are not mutually intelligible. Classification of dialects can be achieved according to two different principles. Linguists usually classify dialects and languages languages genetically (i.e., based on their mutual historical relationships

. The Ethnologue

classifies Otomi languages according to their degrees of mutual intelligibility.

As to the genetic classification of the modern dialects, at least two accounts have been published. Newman and Weitlaner (1950a: 2) arrived at four divisions, three of which they designated "Northeastern", "Northwestern", and "Southwestern". They deemed the dialect of Ixtenco in Tlaxcala to be a major division in itself. They did not provide a detailed list of dialect assignments. Lastra (2001: 24) arrives at largely the same results. The latter scheme includes a complete list of dialect assignments and introduces only slight modifications to the prior scheme, namely: Ixtenco is included with the Sierra dialects and "Northeastern" is renamed "Eastern"; two dialects of the state of Mexico are transferred from Southwestern to Eastern, these being the dialects of two communities close to the western side of Mexico City, San Jerónimo Acazulco and Santiago Tilapa (Tilapa was explicitly assigned to Southwestern by Newman and Weitlaner); and the southernmost dialect of Queretaro, that of the municipio of Amealco

, is transferred from Northwestern to Southwestern. The last revision conflicts with the position of two specialists in this dialect, Hekking and Palancar, who have classified Amealco Otomi in Northwestern, although they too without citing criteria.

The assignment of dialects to the three groups is as follows (following Lastra except in regard to the Amealco dialect):

The Ethnologue divides Otomi into nine groups.

. Three dialects in particular have reached moribund status: those of Ixtenco (Tlaxcala

state), Santiago Tilapa (Mexico state), and Cruz del Palmar (Guanajuato

state). In addition, from the 1920s to the 1980s, the use of indigenous Mexican languages in general was eroded by educational policies that encouraged the "Hispanification" of indigenous communities. All schooling was in Spanish only. As a result, today no group of Otomi speakers has attained general literacy in Otomi, while their literacy rate in Spanish remains far below the national average.33.5% of Otomi speakers are illiterate compared with national average of 8.5% (INEGI, Perfil sociodemográfico, p. 74). In some municipalities the level of monolingualism in Otomi is as high as 22.3% (Huehuetla

, Hidalgo) or 13.1% (Texcatepec

, Veracruz). Monolingualism is normally significantly higher among women than among men.

During the 1990s, however, the Mexican government made a reversal in policies towards indigenous and linguistic rights, prompted by the 1996 adoption of the Universal Declaration of Linguistic Rights

Adopted at a world linguistics conference in Barcelona, it "became a general reference point for the evolution and discussion of linguistic rights in Mexico" (Pellicer et al., "Legislating diversity", p. 132). and domestic social and political agitation by various groups.Such as social and political agitation by the EZLN and indigenous social movements. Decentralized government agencies were created charged with promoting and protecting indigenous communities and languages; these include the National Commission for the Development of Indigenous Peoples (CDI) and the National Institute of Indigenous Languages (INALI)

. In particular, the federal Ley General de Derechos Lingüísticos de los Pueblos Indígenas ("General Law on the Language Rights of the Indigenous Peoples"), promulgated on 13 March 2003, recognizes all of Mexico's indigenous languages, including Otomi, as "national languages", and gives indigenous people the right to speak them in every sphere of public and private life.

Newman and Weitlaner proposed the following reconstruction of the Proto-Otomi phoneme inventory: /p t k (kʷ) ʔ b d ɡ t͡s ʃ h z m n w j/, the oral vowels /i ɨ u e ø o ɛ a ɔ/, and the nasal vowels /ĩ ũ ẽ ɑ̃/. Disregarding the aspirate and ejective series, the reconstruction happens to be nearly identical to inventories of the modern dialects, but in fact many of the stop consonants in the modern varieties are not original (i.e., a /b/ today was often not a *b in the protolanguage).

Words which have an obstruent nasal in tonic syllable feature nasal spreading to all vowels that follow:

However, there is some lack of clarity about the underlying status of nasalization on some vowels:

Nasality can also spread from a nasal root vowel:

the reconstructed Proto-Otomian voiceless nonaspirate stops /p t k/ and now have only the voiced series /b d ɡ/. The only dialects to retain all the original voiceless nonaspirate stops are Otomi of Tilapa, the eastern dialect of San Pablito Pahuatlan in the Sierra Norte de Puebla, and Otomi of Santa Ana Hueytlalpan. A voiceless aspirate stop series /pʰ tʰ kʰ/, derived from earlier clusters of stop + [h], occurs in most dialects, but it has become fricative in Mezquital and Guanajuato dialects /ɸ θ x/. Some dialects have innovated a palatal nasal /ɳ/ from earlier sequences of *j and a nasal vowel. In several dialects, the Proto-Otomi clusters *ʔm and *ʔn before oral vowels have become /ʔb/ and /ʔd/, respectively. In most dialects *n has become /ɾ/, as in the singular determiner and the second person possessive marker. The only dialects to preserve /n/ in these words are the Eastern dialects, and in Tilapa these instances of *n have become /d/.

Many dialects have merged the vowels *ɔ and *a into /a/ as in Mezquital Otomi, whereas others such as Ixtenco Otomi have merged *ɔ with *o. The different dialects have between five and three nasal vowels. In addition to the four nasal vowels of proto-Otomi, some dialects have /õ/. Ixtenco Otomi has only /ẽ ũ ɑ̃/, whereas Toluca Otomi has /ĩ ũ ɑ̃/. In Otomi of Cruz del Palmar, Guanjuato the nasal vowels are /ĩ ũ õ/, the former *ɑ̃ having changed to /õ/. In the late 20th century, Mezquital Otomi was reported by Bernard to be on the verge of losing the distinction between nasal and oral vowels, as he noted that *ɑ̃ had become /ɔ/, that /ĩ ~ i/ and /ũ ~ u/ were in free variation

, and that the only nasal vowel that continued to be distinct from its oral counterpart was /ẽ/. Modern Otomi has borrowed many words from Spanish, in addition to new phonemes that occur only in loan words, such as /l/ apparent in some Otomi dialects instead of the Spanish trilled [r], and /s/, also not present in native Otomi vocabulary.

Otomi is a tonal language, although the exact number of tones claimed to exist varies by dialect and by the phonological analysis that is applied. During the mid-twentieth century, linguists differed regarding the analysis of tones in Otomi. Kenneth Pike, Doris Bartholomew

Otomi is a tonal language, although the exact number of tones claimed to exist varies by dialect and by the phonological analysis that is applied. During the mid-twentieth century, linguists differed regarding the analysis of tones in Otomi. Kenneth Pike, Doris Bartholomew

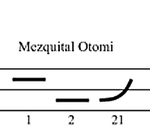

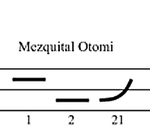

and Eunice Pike preferred an analysis including three tones, but Morris Swadesh

and H. Russell Bernard preferred an analysis with only two tones, in which the rising tone was analyzed as two consecutive tones on one long vowel. In fact, Bernard didn't believe that Otomi should be analyzed as being tonal, as he believed instead that tone in Otomi was not lexical, but rather predictable from other phonetic elements. This analysis was rejected as untenable by the thorouhg analysis of Wallis (1968) and the three tone analysis became the standard; most Otomi dialects have high, low and rising tones. One variety of the Sierra dialect, that of San Gregorio, has been analyzed as having a fourth, falling tone. In Mezquital Otomi, suffixes are never specified for tone, while in Tenango Otomi, the only syllables not specified for tone are prepause syllables and the last syllable of polysyllabic words.

Stress in Otomi is not phonemic but rather falls predictably on every other syllable, with the first syllable of a root always being stressed.

In summary, the basic syllable is CV, though there are also CCV-type syllables like gwa 'foot' and k 'a 'to be wet'. The maximal syllable is (C)CVC, or (C)CVCC word-internally. The way in which closed syllables appear word-internally en Otomí means that there are no native lexemes with closed syllables word-finally. With one exception there are no words of the type CVC#, the exception being CVɾ(the coda =ɾ is an enclitic).

Only a few types of onset clusters are permissible, and are generally /n+C/ and /h,?+C/, along with /mC/, /kw/, /khw/, /pj/, /pk/, and /ʃC/. This last one appears often in grammatical clitic

s. The alveolar nasal combines with every consonant. CCC-onsets with /n/ occur. /nhw/, /n?w/, /n?j/, /n?b/ (this last one being the most frequent and is realized as [m?]).

Coda clusters occur on morpheme boundaries, permissible clusters include: /nd/ (hand.gi 'worm'), /nt/, /?b/, /?p/, /?m/, /hn/, /?mb/

In this article, the orthography of Lastra (various, including 1996, 2006), which marks syllabic tone (see discussion on tone below), is employed. The low tone is unmarked (a), the high level tone is marked with the acute accent (á), and the rising tone with the caron

In this article, the orthography of Lastra (various, including 1996, 2006), which marks syllabic tone (see discussion on tone below), is employed. The low tone is unmarked (a), the high level tone is marked with the acute accent (á), and the rising tone with the caron

(ǎ). Nasal vowels are marked with a rightward curving hook (ogonek

) at the bottom of the vowel letter: į, ę, ą, ų. The letter c denotes [t͡s] and y denotes [j] and palatal sibilant [ʃ] is written with the letter š, and palatal nasal [ɲ] is written ñ. The remaining symbols are from the IPA

with their standard values.

ē and ō for those, and invented extra letters (an e with a tail and a hook and an u with a tail) to represent the central vowels.

used to write modern Otomi have been a focus of controversy among field linguists for many years. Particularly contentious is the issue of whether or not to mark tone, and how, in orthographies to be used by native speakers. Many practical orthographies used by Otomi speakers do not include tone marking. Bartholomew has been a leading advocate for the marking of tone, arguing that because tone is an integrated element of the language's grammatical and lexical systems, the failure to indicate it would lead to ambiguity. Bernard, on the other hand, has argued that native speakers prefer a toneless orthography because they can almost always disambiguate using context, and because they are often unaware of the significance of tone in their language, and consequently have difficulty learning to apply the tone diacritics correctly. For Mezquital Otomi, Bernard accordingly created an orthography in which tone was indicated only when necessary to disambiguate between two words and in which the only symbols used were those available on a standard Spanish language typewriter (employing for example the letter c for [ɔ], v for [ʌ], and the symbol + for [ɨ]).

Practical orthographies used to promote Otomi literacy have been designed and published by the Instituto Lingüístico de Verano

The ILV is the affiliate body of SIL International

in Mexico. and later by the national institute for indigenous languages (INALI). Generally they use diareses ë and ö to distinguish the low mid vowels [ɛ] and [ɔ] from the high mid vowels e and o. High central vowel [ɨ] is generally written or u, and front mid rounded vowel [ø] is written ø or o. Letter a with trema, ä, is sometimes used both for nasal vowel ą and for low back unrounded vowel [ʌ]. Glottalized consonants are written with apostrophe (e.g. tz for [t͡sʔ]) and palatal sibilant [ʃ] is written with x.

in the plural, making for a total of eleven categories of grammatical person in most dialects. The grammatical number of nouns is indicated by the use of articles; the nouns themselves are unmarked for number.

The following atypical pronominal system from Tilapa Otomi lacks the inclusive/exclusive distinction in the first person plural and dual/plural distinction in the second person.

ity is expressed via pronouns and articles. There is no case marking. The possessive formatives may be prefixes or proclitics, depending on the dialect. The particular pattern of possessive inflection is a widespread trait in the Mesoamerican linguistic area

: there is a prefix agreeing in person with the possessor, and if the possessor is plural or dual, then the noun is also marked with a suffix that agrees in number with the possessor. Demonstrated below is the inflectional paradigm for the word /ngų''́/ "house" in the dialect of Toluca.

Classical Otomi, as described by Cárceres, distinguished neutral, honorific, and pejorative definite articles: ąn, neutral singular; o, honorific singular; nø̌, pejorative singular; e, neutral and honorific plural; and yo, pejorative plural.

. In verb inflection, infixation, consonant mutation, and apocope are prominent processes, and the number of irregular verbs is large. Verbs are inflected for either direct object or dative object (but not for both simultaneously) by suffixes. The categories of person of subject, tense, aspect, and mood ("person of subject/T/A/M") are marked simultaneously with a formative which is either a verbal prefix, a proclitic, or a full word, depending perhaps on the dialect and on the analysis of the investigator (they are words in Mezquital, Amealco, and Sierra dialects). The proclitics and words can precede nonverbal predicates. The dialects of Toluca and Ixtenco distinguish the present

, preterit, perfect, imperfect, future

, pluperfect, continuative, imperative

, and two subjunctives. Mezquital Otomi has additional moods. On transitive verbs, the person of the object is marked by a suffix. If either subject or object is dual or plural, it is shown with a plural suffix following the object suffix.

The structure of the Otomi verb is as follows:

The preterit uses the prefixes and ; perfect uses ; imperfect uses ; future uses and ; and pluperfect uses . All tenses use the same suffixes as the present tense for dual and plural numbers and clusivity. To illustrate, the singular forms will be presented. The difference between preterit and imperfect is similar to the distinction between the preterit

in Spanish

: habló 'he spoke (punctual)', and the imperfect hablaba 'he spoke/He used to speak/he was speaking (non-punctual)'.

In Toluca Otomi, the semantic difference between the two subjunctive forms (A and B) has not yet been clearly understood in the linguistic literature. Sometimes subjunctive B has a meaning that is more recent in time than subjunctive A. Both have the meaning of something counterfactual. In other Otomi dialects, such as Otomi of Ixtenco Tlaxcala, the distinction between the two forms is one of subjunctive as opposed to irrealis. The past and present progressive are similar in meaning to English 'was' and 'is X-ing' respectively. The imperative is for issuing direct orders.

Verbs expressing movement towards the speaker such as 'come' use a different set of prefixes for marking person/T/A/M. These prefixes can also be used with other verbs to express 'to do something while coming this way'. In Toluca Otomi mba- is the third person singular imperfect prefix for movement verbs.

To form predicate

s from nouns the subject prefixes are simply added to the noun root:

in Otomi is split between active–stative and accusative systems.

In Toluca Otomi the object suffixes are -gí (first person), -kʔí (second person) and -bi (third person), but the vowel /i/ may harmonize

to /e/ when suffix to a root containing /e/. The first person suffix has is realized as -kí after sibilants and after certain verb roots, and -hkí when used with certain other verbs. The second person object suffix may sometimes metathesis

e to -ʔkí.The third person suffix also has the allomorph

s -hpí/-hpé, -pí, -bí, and sometimes third person objects is marked with a zero morpheme.

Object number (dual or plural) is marked by the same suffixes as are used for the subject, which can lead to ambiguity about the respective numbers of subject and object. With object suffixes of the first or second person, the verbal root sometimes changes, often by the deletion of the final vowel. Note the following examples:

A word class that describes properties or states has been described either as adjectives or as stative verb

s. The members of this class have a meaning of attributing a property to an entity, e.g. "the man is tall", "the house is old". Within this class some roots use the normal subject/T/A/M prefixes, while others always use the object suffixes to encode the person of the patient/subject. The fact that roots in the latter group encode the patient/subject of the predicate using the same suffixes as transitive verbs use to encode the patient/object has been interpreted as a trait of Split intransitivity, and is apparent in all Otomi dialects; but which specific stative verbs take the object prefixes, and the number of prefixes they take, varies between dialects. In Toluca Otomi, most stative verbs are conjugated using a set of suffixes similar to the object/patient suffixes and a third person subject prefix, while only a few use the present continuative subject prefixes. The following are examples of the two kinds of stative verb conjugation in Toluca Otomi:

, but by one analysis there are traces of an emergent active–stative alignment. As for object alignment, it is a direct object language.

Equational clauses can also be complex:

Clauses with a verb can be intransitive or transitive – in Ixtenco Otomi, if a transitive verb has two arguments represented as free noun phrases, usually the subject precedes the verb and the object follows it.

This order also is the norm in clauses where only one constituent is expressed as a free noun phrase. In Ixtenco Otomi verb final word order is used to express focus on the object, and verb initial word order is used to focus on the predicate.

Subordinate clauses usually begin with one of the subordinators such as khandi 'in order to', habɨ 'where', khati 'even though', mba 'when', ngege 'because'. Frequently the future tense is used in the subordinate clause. Relative clauses are normally unheaded, expressed by simple juxtaposition. Different negation particles are used for the verbs "to have", "to be (in a place)" and for imperative clauses.

Interrogative clauses are usually expressed by intonation, but there is also a question particle ši. Information questions use an interrogative pronoun before the predicate.

, Otomi has a vigesimal

number system. The following numerals are from Classical Otomi as described by Cárceres. The e prefixed to all numerals except one is the plural nominal determiner (the a associated with -nʔda being the singular determiner).

(medicinal herb)', while Spanish /l/ can be borrowed as the tap /ɾ/ as in baromaʃi 'dove' from Spanish 'paloma'. Spanish unvoiced stops /p, t, k/ are usually borrowed as their voiced counterparts as in bádú 'duck' from Spanish pato 'duck'. Loanwords from Spanish with stress on the first syllable are usually borrowed with high tone on all syllables as in: sábáná 'blanket' from Spanish sábana 'bedsheet'. Nahuatl loanwords include ndɛ̌nt͡su 'goat' from Nahuatl teːnt͡soneʔ 'goat' (literally "beard possessor").

s the Otomi were well-known for their songs, and a specific genre of Nahuatl

songs called otoncuicatl "Otomi Song" are believed to be translations or reinterpretations of songs originally composed in Otomi. None of the songs written in Otomi during the colonial period have survived; however, beginning in the early 20th century, anthropologists have collected songs performed by modern Otomi singers. The anthropologists Roberto Weitlaner and Jacques Soustelle

collected Otomi songs during the 1930s, and a study of Otomi musical styles was conducted by Vicente T Mendoza. Mendoza found two distinct musical traditions: a religious, and a profane. The religious tradition of songs, with Spanish lyrics, dates to the 16th century, when missionaries such as Pedro de Gante

taught Indians how to construct European style instruments to be used for singing religious hymns. The profane tradition, with Otomi lyrics, possibly dates to pre-Columbian times, and consists of lullabies, joking songs, songs of romance or ballads, and songs involving animals. The following example of an Otomi song about the brevity of life was recollected by Ángel María Garibay K.

in the mid-twentieth century:Originally published in Garibay ("Poemas otomíes", p. 238), republished in phonemic transcription in Lastra (Los Otomíes, pp. 69–70).

Oto-Manguean languages

Oto-Manguean languages are a large family comprising several families of Native American languages. All of the Oto-Manguean languages that are now spoken are indigenous to Mexico, but the Manguean branch of the family, which is now extinct, was spoken as far south as Nicaragua and Costa Rica.The...

and one of the indigenous languages of Mexico, spoken by approximately 240,000 indigenous Otomi people

Otomi people

The Otomi people . Smaller Otomi populations exist in the states of Puebla, Mexico, Tlaxcala, Michoacán and Guanajuato. The Otomi language belonging to the Oto-Pamean branch of the Oto-Manguean language family is spoken in many different varieties some of which are not mutually intelligible.One of...

in the central altiplano

Mexican Plateau

The Central Mexican Plateau, also known as the Mexican Altiplano or Altiplanicie Mexicana, is a large arid-to-semiarid plateau that occupies much of northern and central Mexico...

region of Mexico

Mexico

The United Mexican States , commonly known as Mexico , is a federal constitutional republic in North America. It is bordered on the north by the United States; on the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; on the southeast by Guatemala, Belize, and the Caribbean Sea; and on the east by the Gulf of...

. The language is spoken in many different dialects, some of which are not mutually intelligible

Mutual intelligibility

In linguistics, mutual intelligibility is recognized as a relationship between languages or dialects in which speakers of different but related languages can readily understand each other without intentional study or extraordinary effort...

, therefore it is in effect a dialect continuum

Dialect continuum

A dialect continuum, or dialect area, was defined by Leonard Bloomfield as a range of dialects spoken across some geographical area that differ only slightly between neighboring areas, but as one travels in any direction, these differences accumulate such that speakers from opposite ends of the...

. The word Hñähñu hɲɑ̃hɲṹ has been proposed as an endonym, but since it represents the usage of a single dialect it has not gained wide currency. Linguists have classified the modern dialects into three dialect areas: the Northwestern dialects spoken in Querétaro

Querétaro

Querétaro officially Estado Libre y Soberano de Querétaro de Arteaga is one of the 31 states which, with the Federal District, comprise the 32 Federal Entities of Mexico. It is divided into 18 municipalities and its capital city is Santiago de Querétaro....

, Hidalgo and Guanajuato

Guanajuato

Guanajuato officially Estado Libre y Soberano de Guanajuato is one of the 31 states which, with the Federal District, comprise the 32 Federal Entities of Mexico. It is divided in 46 municipalities and its capital city is Guanajuato....

; the Southwestern dialects spoken in the State of Mexico

Mexico (state)

México , officially: Estado Libre y Soberano de México is one of the 31 states which, with the Federal District, comprise the 32 Federal Entities of the United Mexican States. It is divided in 125 municipalities and its capital city is Toluca de Lerdo....

; and the Eastern dialects spoken in the highlands of Veracruz

Veracruz

Veracruz, formally Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave officially Estado Libre y Soberano de Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave , is one of the 31 states that, along with the Federal District, comprise the 32 federative entities of Mexico. It is divided in 212 municipalities and its capital city is...

, Puebla

Puebla

Puebla officially Estado Libre y Soberano de Puebla is one of the 31 states which, with the Federal District, comprise the 32 Federal Entities of Mexico. It is divided in 217 municipalities and its capital city is Puebla....

, and eastern Hidalgo and in villages in Tlaxcala

Tlaxcala

Tlaxcala officially Estado Libre y Soberano de Tlaxcala is one of the 31 states which along with the Federal District comprise the 32 federative entities of Mexico. It is divided into 60 municipalities and its capital city is Tlaxcala....

and Mexico states.

Like all other Oto-Manguean languages, Otomi is a tonal language and most varieties distinguish three tones. Nouns are marked only for possessor; plural number is marked by the definite article and by a verb suffix, and some dialects maintain the historically existing dual number marking. There is no case marking. Verb morphology can be described as either fusional or agglutinating

Morphological typology

Morphological typology is a way of classifying the languages of the world that groups languages according to their common morphological structures. First developed by brothers Friedrich von Schlegel and August von Schlegel, the field organizes languages on the basis of how those languages form...

depending on analysis. In verb inflection, infixation, consonant mutation, and apocope are prominent processes, and the number of irregular verbs is large. The grammatical subject

Subject (grammar)

The subject is one of the two main constituents of a clause, according to a tradition that can be tracked back to Aristotle and that is associated with phrase structure grammars; the other constituent is the predicate. According to another tradition, i.e...

in a sentence is cross referenced by a class of morpheme

Morpheme

In linguistics, a morpheme is the smallest semantically meaningful unit in a language. The field of study dedicated to morphemes is called morphology. A morpheme is not identical to a word, and the principal difference between the two is that a morpheme may or may not stand alone, whereas a word,...

s that can be analysed as either proclitics or prefix

Prefix

A prefix is an affix which is placed before the root of a word. Particularly in the study of languages,a prefix is also called a preformative, because it alters the form of the words to which it is affixed.Examples of prefixes:...

es and which also mark for tense

Grammatical tense

A tense is a grammatical category that locates a situation in time, to indicate when the situation takes place.Bernard Comrie, Aspect, 1976:6:...

, aspect

Grammatical aspect

In linguistics, the grammatical aspect of a verb is a grammatical category that defines the temporal flow in a given action, event, or state, from the point of view of the speaker...

and mood

Grammatical mood

In linguistics, grammatical mood is a grammatical feature of verbs, used to signal modality. That is, it is the use of verbal inflections that allow speakers to express their attitude toward what they are saying...

. Verbs are inflected for either direct object or dative object (but not for both simultaneously) by suffixes. Inclusive 'we' and exclusive 'we' are distinguished (the clusivity

Clusivity

In linguistics, clusivity is a distinction between inclusive and exclusive first-person pronouns and verbal morphology, also called inclusive "we" and exclusive "we"...

distinction). Otomi syntax generally has nominative–accusative alignment

Morphosyntactic alignment

In linguistics, morphosyntactic alignment is the system used to distinguish between the arguments of transitive verbs and those of intransitive verbs...

with some traits of active–stative alignment

Active-stative language

An active–stative language or split intransitive language, is one in which the sole argument of an intransitive verb is sometimes marked in the same way as the agent of a transitive verb , and sometimes in the same way as the direct object of a transitive verb.The case of the...

.

After the Spanish conquest Otomi became a written language when friars taught the Otomi to write the language using the Latin alphabet

Latin alphabet

The Latin alphabet, also called the Roman alphabet, is the most recognized alphabet used in the world today. It evolved from a western variety of the Greek alphabet called the Cumaean alphabet, which was adopted and modified by the Etruscans who ruled early Rome...

; the written language of the colonial period is often called Classical Otomi

Classical Otomi

Classical Otomi is the name used for the Otomi language as spoken in the early centuries of Spanish colonial rule in Mexico and documented by Spanish friars who learned the language in order to catechize the Otomi peoples. During the colonial period, many Otomis learned to write their language in...

. Several codices

Codex

A codex is a book in the format used for modern books, with multiple quires or gatherings typically bound together and given a cover.Developed by the Romans from wooden writing tablets, its gradual replacement...

and grammars were composed in Classical Otomi. A negative stereotype of the Otomi promoted by the Nahuas and perpetuated by the Spanish resulted in a loss of status for the Otomi, who began to abandon their language in favor of Spanish. The attitude of the larger world toward the Otomi language began to change in 2003 when Otomi was granted recognition as a national language under Mexican law together with 61 other indigenous languages.

Language name

The name Otomi comes from the NahuatlNahuatl

Nahuatl is thought to mean "a good, clear sound" This language name has several spellings, among them náhuatl , Naoatl, Nauatl, Nahuatl, Nawatl. In a back formation from the name of the language, the ethnic group of Nahuatl speakers are called Nahua...

otomitl, which is possibly derived from an older word totomitl "shooter of birds". It is not an Otomi endonym; the Otomi refer to themselves as Hñähñú, Hñähño, Hñotho, Hñähü, Hñätho, Yųhų, Yųhmų, Ñųhų, or Ñañhų depending on which dialect of Otomi they speak.See List of Otomi languages for information about which dialect areas use which terms. Most of the variant forms are composed of two morpheme

Morpheme

In linguistics, a morpheme is the smallest semantically meaningful unit in a language. The field of study dedicated to morphemes is called morphology. A morpheme is not identical to a word, and the principal difference between the two is that a morpheme may or may not stand alone, whereas a word,...

s meaning "speak" and "well" respectively.

The word Otomi entered the Spanish language through Nahuatl and is used to describe the larger Otomi macroethnic group and the dialect continuum. From Spanish the word Otomi has become entrenched in the linguistic and anthropological literature. Among linguists, the suggestion has been made to change the academic designation from Otomi to Hñähñú, the endonym used by the Otomi of the Mezquital valley; however, no common endonym exists for all dialects of the language.

External classification

The Otomi language belongs to the Oto-PameanOto-Pamean languages

The Oto-Pamean languages are a branch of the Oto-Manguean languages of central Mexico that includes are half a dozen languages, or more accurately dialect clusters:*Otomian: Otomi, Mazahua*Matlatzinca*Pamean*Chichimeca...

branch of the Oto-Manguean languages

Oto-Manguean languages

Oto-Manguean languages are a large family comprising several families of Native American languages. All of the Oto-Manguean languages that are now spoken are indigenous to Mexico, but the Manguean branch of the family, which is now extinct, was spoken as far south as Nicaragua and Costa Rica.The...

. Within Oto-Pamean it is part of the Otomian subgroup which also includes Mazahua, Matlatzinca

Matlatzinca language

The Matlatzinca language, also called Tlahuica or Ocuiltec, is an indigenous language of Mexico spoken by the Matlatzinca people in the southern part of the State of Mexico. It is an Oto-Manguean language of the Oto-Pamean subgroup...

and Ocuilteco/Tlahuica

Matlatzinca language

The Matlatzinca language, also called Tlahuica or Ocuiltec, is an indigenous language of Mexico spoken by the Matlatzinca people in the southern part of the State of Mexico. It is an Oto-Manguean language of the Oto-Pamean subgroup...

.

History

The Oto-Pamean languages may have split from the other Oto-Manguean languages around 3500 BC. Within the Otomian branch, Proto-Otomi seems to have split from Proto-Mazahua ca. 500 AD. Around 1000 AD, Proto-Otomi began diversifying into the modern Otomi varieties.Proto-Otomi period and later precolonial period

Much of central Mexico was inhabited by speakers of the Oto-Pamean languages before the arrival of Nahuatl speakers; beyond this, the geographical distribution of the ancestral stages of most modern indigenous languages of Mexico, and their associations with various civilizations, remain undetermined. It has been proposed that Proto-Otomi-Mazahua most likely was one of the languages spoken in TeotihuacanTeotihuacan

Teotihuacan – also written Teotihuacán, with a Spanish orthographic accent on the last syllable – is an enormous archaeological site in the Basin of Mexico, just 30 miles northeast of Mexico City, containing some of the largest pyramidal structures built in the pre-Columbian Americas...

, the greatest Mesoamerican ceremonial center of the Classic period, whose demise occurred ca. 600 AD.

The Precolumbian

Pre-Columbian

The pre-Columbian era incorporates all period subdivisions in the history and prehistory of the Americas before the appearance of significant European influences on the American continents, spanning the time of the original settlement in the Upper Paleolithic period to European colonization during...

Otomi people did not have a proper writing system

Writing system

A writing system is a symbolic system used to represent elements or statements expressible in language.-General properties:Writing systems are distinguished from other possible symbolic communication systems in that the reader must usually understand something of the associated spoken language to...

, but the largely ideographic Aztec writing

Aztec writing

Aztec or Nahuatl writing is a pictographic and ideographic pre-Columbian writing system used in central Mexico by the Nahua peoples. The majority of the Aztec codices were burned either by Aztec tlatoani , or by Spanish clergy following the conquest of Mesoamerica...

could be read in Otomi as well as Nahuatl. The Otomi often translated names of places or rulers into Otomi rather than using the Nahuatl names. For example, the Nahuatl place name Tenochtitlān, "place of Opuntia cactus", was rendered as *ʔmpôndo in proto-Otomi, with the same meaning.In most modern varieties of Otomi the name for "Mexico" has changed to ʔmôndo (in Ixtenco Otomi) or ʔmóndá (in Mezquital Otomi). In some varieties of Highland Otomi it is mbôndo. Only Tilapa Otomi and Acazulco Otomi preserve the original pronunciation (Lastra, Los Otomíes, p. 47).

Colonial period and Classical Otomi

Jalisco

Jalisco officially Estado Libre y Soberano de Jalisco is one of the 31 states which, with the Federal District, comprise the 32 Federal Entities of Mexico. It is located in Western Mexico and divided in 125 municipalities and its capital city is Guadalajara.It is one of the more important states...

and Michoacan

Michoacán

Michoacán officially Estado Libre y Soberano de Michoacán de Ocampo is one of the 31 states which, with the Federal District, comprise the 32 Federal Entities of Mexico. It is divided in 113 municipalities and its capital city is Morelia...

. After the conquest, the Otomi people experienced a period of geographical expansion as the Spaniards employed Otomi warriors in their expeditions of conquest into northern Mexico. During and after the Mixtón rebellion

Mixtón Rebellion

The Mixtón War was fought from 1540 until 1542 between Spanish invaders and their Aztec and Tlaxcalan allies against the Caxcanes and other semi-nomadic Indians of the area of north western Mexico...

, in which Otomi warriors fought for the Spanish, Otomis settled areas in Querétaro (where they founded the city of Querétaro) and Guanajuato which previously had been inhabited by nomadic Chichimecs. Because Spanish colonial historians such as Bernardino de Sahagún

Bernardino de Sahagún

Bernardino de Sahagún was a Franciscan friar, missionary priest and pioneering ethnographer who participated in the Catholic evangelization of colonial New Spain . Born in Sahagún, Spain, in 1499, he journeyed to New Spain in 1529, and spent more than 50 years conducting interviews regarding Aztec...

used primarily Nahua speakers as sources for their histories of the colony, the Nahuas' negative image of the Otomi people was perpetuated throughout the colonial period, which contributed to the Otomi gradually abandoning their language.

"Classical Otomi

Classical Otomi

Classical Otomi is the name used for the Otomi language as spoken in the early centuries of Spanish colonial rule in Mexico and documented by Spanish friars who learned the language in order to catechize the Otomi peoples. During the colonial period, many Otomis learned to write their language in...

" is the term used to define the Otomi spoken in the early centuries of colonial rule. This historical stage of the language was given Latin orthography and documented by Spanish friars who learned it in order to proselytize the Otomi peoples. Text in Classical Otomi is not readily comprehensible, since the Spanish speaking friars failed to differentiate the varied vowel and consonant sounds of the Otomi language. Friars and monks from the Spanish mendicant orders such as the Franciscans wrote Otomi grammars, the earliest of which is that of Friar Pedro de Cárceres' Arte de la lengua othomí [sic], written perhaps as early as 1580, but not published until 1907 In 1605, Alonso de Urbano wrote a trilingual Spanish-Nahuatl

Nahuatl

Nahuatl is thought to mean "a good, clear sound" This language name has several spellings, among them náhuatl , Naoatl, Nauatl, Nahuatl, Nawatl. In a back formation from the name of the language, the ethnic group of Nahuatl speakers are called Nahua...

-Otomi dictionary, which also included a small set of grammatical notes about Otomi. The grammarian of Nahuatl, Horacio Carochi

Horacio Carochi

Horacio Carochi was an Italian Jesuit priest and grammarian who was born in Florence, Italy, and died in Mexico. He is known for his grammar of the Classical Nahuatl language.- Life:...

is known to have written a grammar of Otomi, but no copies have survived. In the latter half of the eighteenth century, an anonymous Jesuit friar wrote the grammar Luces del Otomi, and Neve y Molina wrote a dictionary and a grammar.

During the colonial period, many Otomis were taught to read and write their language. In consequence, a significant number of documents in Otomi exist from the period, both secular and religious, the most well-known of which are the Codices of Huichapan and Jilotepec.

After the colonial period ended in 1813, the Otomi were no longer recognized as an indigenous group, the Otomi language lost its status as a language of education, and the period of Classical Otomi as a literary language ended.

Modern Otomi internal classification

Otomi is traditionally described as a single language, although its many dialects are not all mutually intelligible. The language classification of the SIL International's EthnologueEthnologue

Ethnologue: Languages of the World is a web and print publication of SIL International , a Christian linguistic service organization, which studies lesser-known languages, to provide the speakers with Bibles in their native language and support their efforts in language development.The Ethnologue...

considers Otomi to be a cover term for nine separate Otomi languages and assigns a different ISO code to each of these nine varieties. Other linguists however, consider Otomi to be the best name for a dialect continuum

Dialect continuum

A dialect continuum, or dialect area, was defined by Leonard Bloomfield as a range of dialects spoken across some geographical area that differ only slightly between neighboring areas, but as one travels in any direction, these differences accumulate such that speakers from opposite ends of the...

that is clearly demarcated from its closest relative, Mazahua

Mazahua language

The Mazahua language is an indigenous language of Mexico, spoken in the country's central states by the ethnic group widely known as the Mazahua but who refer to themselves as Hñatho. Mazahua is a Mesoamerican language and shows many of the traits which define the Mesoamerican Linguistic Area...

. For the purposes of this article, the latter approach will be followed.

Currently Otomi dialects are spoken collectively by circa 239,000 speakers—some 5 to 6 percent of whom are monolingual—in widely scattered districts (see map). The highest concentration of speakers is found in the Valle de Mezquital region of Hidalgo and in the southern portion of Querétaro

Querétaro

Querétaro officially Estado Libre y Soberano de Querétaro de Arteaga is one of the 31 states which, with the Federal District, comprise the 32 Federal Entities of Mexico. It is divided into 18 municipalities and its capital city is Santiago de Querétaro....

, where some municipalities have concentrations of Otomi speakers as high as 60–70%. Because of recent migratory patterns, small populations of Otomi speakers can be found in new locations throughout Mexico and in the United States.

Dialectal diversity in Otomi is so great that some dialects are not mutually intelligible. Classification of dialects can be achieved according to two different principles. Linguists usually classify dialects and languages languages genetically (i.e., based on their mutual historical relationships

Historical linguistics

Historical linguistics is the study of language change. It has five main concerns:* to describe and account for observed changes in particular languages...

. The Ethnologue

Ethnologue

Ethnologue: Languages of the World is a web and print publication of SIL International , a Christian linguistic service organization, which studies lesser-known languages, to provide the speakers with Bibles in their native language and support their efforts in language development.The Ethnologue...

classifies Otomi languages according to their degrees of mutual intelligibility.

As to the genetic classification of the modern dialects, at least two accounts have been published. Newman and Weitlaner (1950a: 2) arrived at four divisions, three of which they designated "Northeastern", "Northwestern", and "Southwestern". They deemed the dialect of Ixtenco in Tlaxcala to be a major division in itself. They did not provide a detailed list of dialect assignments. Lastra (2001: 24) arrives at largely the same results. The latter scheme includes a complete list of dialect assignments and introduces only slight modifications to the prior scheme, namely: Ixtenco is included with the Sierra dialects and "Northeastern" is renamed "Eastern"; two dialects of the state of Mexico are transferred from Southwestern to Eastern, these being the dialects of two communities close to the western side of Mexico City, San Jerónimo Acazulco and Santiago Tilapa (Tilapa was explicitly assigned to Southwestern by Newman and Weitlaner); and the southernmost dialect of Queretaro, that of the municipio of Amealco

Amealco de Bonfil

Amealco is a municipality in the Mexican state of Querétaro. Its name is thought to mean place of springs in Nahuatl. The municipality seat, also called Amealco, is located 63 km southeast of Santiago de Querétaro. Its elevation is 2,605 meters above sea level, and the annual temperature...

, is transferred from Northwestern to Southwestern. The last revision conflicts with the position of two specialists in this dialect, Hekking and Palancar, who have classified Amealco Otomi in Northwestern, although they too without citing criteria.

| Region | Count | PercentagePercentages given are in comparison to the total Otomi speaking population. |

|---|---|---|

| Federal District | 12,460 | 5.2% |

| Querétaro Querétaro Querétaro officially Estado Libre y Soberano de Querétaro de Arteaga is one of the 31 states which, with the Federal District, comprise the 32 Federal Entities of Mexico. It is divided into 18 municipalities and its capital city is Santiago de Querétaro.... |

18,933 | 8.0% |

| Hidalgo | 95,057 | 39.7% |

| Mexico (state) | 83,362 | 34.9% |

| Jalisco Jalisco Jalisco officially Estado Libre y Soberano de Jalisco is one of the 31 states which, with the Federal District, comprise the 32 Federal Entities of Mexico. It is located in Western Mexico and divided in 125 municipalities and its capital city is Guadalajara.It is one of the more important states... |

1,089 | 0.5% |

| Guanajuato Guanajuato Guanajuato officially Estado Libre y Soberano de Guanajuato is one of the 31 states which, with the Federal District, comprise the 32 Federal Entities of Mexico. It is divided in 46 municipalities and its capital city is Guanajuato.... |

721 | 0.32% |

| Puebla Puebla Puebla officially Estado Libre y Soberano de Puebla is one of the 31 states which, with the Federal District, comprise the 32 Federal Entities of Mexico. It is divided in 217 municipalities and its capital city is Puebla.... |

7,253 | 3.0% |

| Michoacán Michoacán Michoacán officially Estado Libre y Soberano de Michoacán de Ocampo is one of the 31 states which, with the Federal District, comprise the 32 Federal Entities of Mexico. It is divided in 113 municipalities and its capital city is Morelia... |

480 | 0.2% |

| Nuevo León Nuevo León Nuevo León It is located in Northeastern Mexico. It is bordered by the states of Tamaulipas to the north and east, San Luis Potosí to the south, and Coahuila to the west. To the north, Nuevo León has a 15 kilometer stretch of the U.S.-Mexico border adjacent to the U.S... |

1,126 | 0.5% |

| Veracruz Veracruz Veracruz, formally Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave officially Estado Libre y Soberano de Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave , is one of the 31 states that, along with the Federal District, comprise the 32 federative entities of Mexico. It is divided in 212 municipalities and its capital city is... |

16,822 | 7.0% |

| Rest of Mexico | 2,537 | 1.20% |

| Total: | 239,850 | 100% |

The assignment of dialects to the three groups is as follows (following Lastra except in regard to the Amealco dialect):

- The Eastern group, including all dialects spoken east of the Valle del Mezquital in the center of the State of Hidalgo plus two village dialects from the State of Mexico; specifically: the Highland dialects (the Ethnologue's Highland Otomi, Texcatepec Otomi and Tenango Otomi), Otomi of Santa Ana Hueytlalpan, as well as three dialects geographically distant from the preceding: the dialects of Tilapa and Acazulco in the state of Mexico, and finally the dialect of Ixtenco (Tlaxcala).

- The Northwestern area, comprising the dialects of Mezquital, Querétaro, and Guanajuato.

- The Southwestern group, including the so called State of Mexico dialect, Otomi of Chapa de Mota, Otomi of Jilotepec, Toluca Otomi, and Otomi of San Felipe los Alzatí, Michoacan. (In point of fact, all the foregoing, except of course for Alzatí, are spoken in the northern half of western lobe of the State of Mexico.)

The Ethnologue divides Otomi into nine groups.

Otomi as an endangered language

Although Otomi is vigorous in some areas, with children acquiring the language through natural transmission (e.g. in the Mezquital valley of Hidalgo and in the Highlands), overall it is an endangered languageEndangered language

An endangered language is a language that is at risk of falling out of use. If it loses all its native speakers, it becomes a dead language. If eventually no one speaks the language at all it becomes an "extinct language"....

. Three dialects in particular have reached moribund status: those of Ixtenco (Tlaxcala

Tlaxcala

Tlaxcala officially Estado Libre y Soberano de Tlaxcala is one of the 31 states which along with the Federal District comprise the 32 federative entities of Mexico. It is divided into 60 municipalities and its capital city is Tlaxcala....

state), Santiago Tilapa (Mexico state), and Cruz del Palmar (Guanajuato

Guanajuato

Guanajuato officially Estado Libre y Soberano de Guanajuato is one of the 31 states which, with the Federal District, comprise the 32 Federal Entities of Mexico. It is divided in 46 municipalities and its capital city is Guanajuato....

state). In addition, from the 1920s to the 1980s, the use of indigenous Mexican languages in general was eroded by educational policies that encouraged the "Hispanification" of indigenous communities. All schooling was in Spanish only. As a result, today no group of Otomi speakers has attained general literacy in Otomi, while their literacy rate in Spanish remains far below the national average.33.5% of Otomi speakers are illiterate compared with national average of 8.5% (INEGI, Perfil sociodemográfico, p. 74). In some municipalities the level of monolingualism in Otomi is as high as 22.3% (Huehuetla

Huehuetla

Huehuetla is a town and one of the 84 municipalities of Hidalgo, in central-eastern Mexico. The municipality covers an area of 262.1 km².As of 2005, the municipality had a total population of 22,927....

, Hidalgo) or 13.1% (Texcatepec

Texcatepec

Texcatepec is a municipality located in the north zone in the State of Veracruz, about 190 km from state capital Xalapa. It has a surface of 153.61 km2. It is located at...

, Veracruz). Monolingualism is normally significantly higher among women than among men.

During the 1990s, however, the Mexican government made a reversal in policies towards indigenous and linguistic rights, prompted by the 1996 adoption of the Universal Declaration of Linguistic Rights

Universal Declaration of Linguistic Rights

The Universal Declaration of Linguistic Rights is a document signed by UNESCO, the PEN Clubs, and several non-governmental organizations in 1996 to support linguistic rights, especially those of endangered languages...

Adopted at a world linguistics conference in Barcelona, it "became a general reference point for the evolution and discussion of linguistic rights in Mexico" (Pellicer et al., "Legislating diversity", p. 132). and domestic social and political agitation by various groups.Such as social and political agitation by the EZLN and indigenous social movements. Decentralized government agencies were created charged with promoting and protecting indigenous communities and languages; these include the National Commission for the Development of Indigenous Peoples (CDI) and the National Institute of Indigenous Languages (INALI)

Instituto Nacional de Lenguas Indígenas

The Instituto Nacional de Lenguas Indígenas is a Mexican federal public agency, created 13 March 2003 by the enactment of the Ley General de Derechos Lingüísticos de los Pueblos Indígenas by the administration of President Vicente Fox...

. In particular, the federal Ley General de Derechos Lingüísticos de los Pueblos Indígenas ("General Law on the Language Rights of the Indigenous Peoples"), promulgated on 13 March 2003, recognizes all of Mexico's indigenous languages, including Otomi, as "national languages", and gives indigenous people the right to speak them in every sphere of public and private life.

Phoneme inventory

The following phonological description is that of the dialect of San ildefonso Tultepec, Querétaro as described by Palancar 2009. This is because it is the dialect for which the most complete phonological description is available and it is also similar to the system found in the Valle del Mezquital variety, which is the most widely spoken Otomian variety.| Bilabial Bilabial consonant In phonetics, a bilabial consonant is a consonant articulated with both lips. The bilabial consonants identified by the International Phonetic Alphabet are:... |

Dental | Alveolar Alveolar consonant Alveolar consonants are articulated with the tongue against or close to the superior alveolar ridge, which is called that because it contains the alveoli of the superior teeth... |

Palatal Palatal consonant Palatal consonants are consonants articulated with the body of the tongue raised against the hard palate... |

Velar Velar consonant Velars are consonants articulated with the back part of the tongue against the soft palate, the back part of the roof of the mouth, known also as the velum).... |

Glottal Glottal consonant Glottal consonants, also called laryngeal consonants, are consonants articulated with the glottis. Many phoneticians consider them, or at least the so-called fricative, to be transitional states of the glottis without a point of articulation as other consonants have; in fact, some do not consider... |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stop Stop consonant In phonetics, a plosive, also known as an occlusive or an oral stop, is a stop consonant in which the vocal tract is blocked so that all airflow ceases. The occlusion may be done with the tongue , lips , and &... |

ejective Ejective consonant In phonetics, ejective consonants are voiceless consonants that are pronounced with simultaneous closure of the glottis. In the phonology of a particular language, ejectives may contrast with aspirated or tenuis consonants... |

[tʼ] | [tsʼ] | [tʃʼ] | [kʼ] | ||

| unaspirated | p | t | t͡s | t͡ʃ | k | ʔ | |

| Fricative Fricative consonant Fricatives are consonants produced by forcing air through a narrow channel made by placing two articulators close together. These may be the lower lip against the upper teeth, in the case of ; the back of the tongue against the soft palate, in the case of German , the final consonant of Bach; or... |

voiced Voice (phonetics) Voice or voicing is a term used in phonetics and phonology to characterize speech sounds, with sounds described as either voiceless or voiced. The term, however, is used to refer to two separate concepts. Voicing can refer to the articulatory process in which the vocal cords vibrate... |

b | d | z | ɡ | ||

| voiceless | ɸ | θ | s | ʃ | x | h | |

| Nasal Nasal consonant A nasal consonant is a type of consonant produced with a lowered velum in the mouth, allowing air to escape freely through the nose. Examples of nasal consonants in English are and , in words such as nose and mouth.- Definition :... |

m | n | ɲ | ||||

| Rhotic Rhotic consonant In phonetics, rhotic consonants, also called tremulants or "R-like" sounds, are liquid consonants that are traditionally represented orthographically by symbols derived from the Greek letter rho, including "R, r" from the Roman alphabet and "Р, p" from the Cyrillic alphabet... |

r~ɾ | ||||||

| Approximant Approximant consonant Approximants are speech sounds that involve the articulators approaching each other but not narrowly enough or with enough articulatory precision to create turbulent airflow. Therefore, approximants fall between fricatives, which do produce a turbulent airstream, and vowels, which produce no... |

lateral Lateral consonant A lateral is an el-like consonant, in which airstream proceeds along the sides of the tongue, but is blocked by the tongue from going through the middle of the mouth.... |

l | |||||

| central Central consonant A central or medial consonant is a consonant sound that is produced when air flows across the center of the mouth over the tongue. The class contrasts with lateral consonants, in which air flows over the sides of the tongue rather than down its center.... |

w | j | |||||

| Front Front vowel A front vowel is a type of vowel sound used in some spoken languages. The defining characteristic of a front vowel is that the tongue is positioned as far in front as possible in the mouth without creating a constriction that would be classified as a consonant. Front vowels are sometimes also... |

Central Central vowel A central vowel is a type of vowel sound used in some spoken languages. The defining characteristic of a central vowel is that the tongue is positioned halfway between a front vowel and a back vowel... |

Back Back vowel A back vowel is a type of vowel sound used in spoken languages. The defining characteristic of a back vowel is that the tongue is positioned as far back as possible in the mouth without creating a constriction that would be classified as a consonant. Back vowels are sometimes also called dark... |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| oral | nasal | oral | nasal | oral | nasal | |

| Close Close vowel A close vowel is a type of vowel sound used in many spoken languages. The defining characteristic of a close vowel is that the tongue is positioned as close as possible to the roof of the mouth without creating a constriction that would be classified as a consonant.This term is prescribed by the... |

i | [ĩ] | ɨ | u | [ũ] | |

| Close-mid Close-mid vowel A close-mid vowel is a type of vowel sound used in some spoken languages. The defining characteristic of a close-mid vowel is that the tongue is positioned two-thirds of the way from a close vowel to a mid vowel... |

e | ə | o | [õ] | ||

| Near-open Near-open vowel A near-open vowel is a type of vowel sound used in some spoken languages. The defining characteristic of a near-open vowel is that the tongue is positioned similarly to an open vowel, but slightly more constricted. Near-open vowels are sometimes described as lax variants of the fully open vowels... |

ɛ | [ɛ̃] | ɔ | |||

| Open Open vowel An open vowel is defined as a vowel sound in which the tongue is positioned as far as possible from the roof of the mouth. Open vowels are sometimes also called low vowels in reference to the low position of the tongue... |

a | [ã] | ||||

Newman and Weitlaner proposed the following reconstruction of the Proto-Otomi phoneme inventory: /p t k (kʷ) ʔ b d ɡ t͡s ʃ h z m n w j/, the oral vowels /i ɨ u e ø o ɛ a ɔ/, and the nasal vowels /ĩ ũ ẽ ɑ̃/. Disregarding the aspirate and ejective series, the reconstruction happens to be nearly identical to inventories of the modern dialects, but in fact many of the stop consonants in the modern varieties are not original (i.e., a /b/ today was often not a *b in the protolanguage).

Realization of nasality

The most common nasal is the alveolar. This phoneme has many allophones. It is default [n], but it may also surface as [m] before a labial stop or as the palatal ɲ when preceding a glottal (though there are exceptions).Words which have an obstruent nasal in tonic syllable feature nasal spreading to all vowels that follow:

- /'maʔ.tʼi/ ['mãʔ.tʼɛ̃] 'to call someone'

However, there is some lack of clarity about the underlying status of nasalization on some vowels:

- /'ɲũ.ni/ ['ɲũ.nɛ̃] 'to eat'

Nasality can also spread from a nasal root vowel:

- /'tʼõ.ʃi/ ['tʼõʃɛ̃] 'chivo'

Phonological diversity of the modern dialects

Modern dialects have undergone various changes from the common historic phonemic inventory. Most have voicedVoice (phonetics)

Voice or voicing is a term used in phonetics and phonology to characterize speech sounds, with sounds described as either voiceless or voiced. The term, however, is used to refer to two separate concepts. Voicing can refer to the articulatory process in which the vocal cords vibrate...

the reconstructed Proto-Otomian voiceless nonaspirate stops /p t k/ and now have only the voiced series /b d ɡ/. The only dialects to retain all the original voiceless nonaspirate stops are Otomi of Tilapa, the eastern dialect of San Pablito Pahuatlan in the Sierra Norte de Puebla, and Otomi of Santa Ana Hueytlalpan. A voiceless aspirate stop series /pʰ tʰ kʰ/, derived from earlier clusters of stop + [h], occurs in most dialects, but it has become fricative in Mezquital and Guanajuato dialects /ɸ θ x/. Some dialects have innovated a palatal nasal /ɳ/ from earlier sequences of *j and a nasal vowel. In several dialects, the Proto-Otomi clusters *ʔm and *ʔn before oral vowels have become /ʔb/ and /ʔd/, respectively. In most dialects *n has become /ɾ/, as in the singular determiner and the second person possessive marker. The only dialects to preserve /n/ in these words are the Eastern dialects, and in Tilapa these instances of *n have become /d/.

Many dialects have merged the vowels *ɔ and *a into /a/ as in Mezquital Otomi, whereas others such as Ixtenco Otomi have merged *ɔ with *o. The different dialects have between five and three nasal vowels. In addition to the four nasal vowels of proto-Otomi, some dialects have /õ/. Ixtenco Otomi has only /ẽ ũ ɑ̃/, whereas Toluca Otomi has /ĩ ũ ɑ̃/. In Otomi of Cruz del Palmar, Guanjuato the nasal vowels are /ĩ ũ õ/, the former *ɑ̃ having changed to /õ/. In the late 20th century, Mezquital Otomi was reported by Bernard to be on the verge of losing the distinction between nasal and oral vowels, as he noted that *ɑ̃ had become /ɔ/, that /ĩ ~ i/ and /ũ ~ u/ were in free variation

Free variation

Free variation in linguistics is the phenomenon of two sounds or forms appearing in the same environment without a change in meaning and without being considered incorrect by native speakers...

, and that the only nasal vowel that continued to be distinct from its oral counterpart was /ẽ/. Modern Otomi has borrowed many words from Spanish, in addition to new phonemes that occur only in loan words, such as /l/ apparent in some Otomi dialects instead of the Spanish trilled [r], and /s/, also not present in native Otomi vocabulary.

Tone and stress

Doris Bartholomew

Doris Aileen Bartholomew is an American linguist whose published research specialises in the lexicography, historical and descriptive linguistics for indigenous languages in Mexico, in particular for Oto-Manguean languages. Bartholomew's extensive publications on Mesoamerican languages span five...

and Eunice Pike preferred an analysis including three tones, but Morris Swadesh

Morris Swadesh

Morris Swadesh was an influential and controversial American linguist. In his work, he applied basic concepts in historical linguistics to the Indigenous languages of the Americas...

and H. Russell Bernard preferred an analysis with only two tones, in which the rising tone was analyzed as two consecutive tones on one long vowel. In fact, Bernard didn't believe that Otomi should be analyzed as being tonal, as he believed instead that tone in Otomi was not lexical, but rather predictable from other phonetic elements. This analysis was rejected as untenable by the thorouhg analysis of Wallis (1968) and the three tone analysis became the standard; most Otomi dialects have high, low and rising tones. One variety of the Sierra dialect, that of San Gregorio, has been analyzed as having a fourth, falling tone. In Mezquital Otomi, suffixes are never specified for tone, while in Tenango Otomi, the only syllables not specified for tone are prepause syllables and the last syllable of polysyllabic words.

Stress in Otomi is not phonemic but rather falls predictably on every other syllable, with the first syllable of a root always being stressed.

Syllable structure

Phonological words never end in a consonant. A number of initial consonant clusters have developed from the loss of a medial vowel: e.g., the first person continuative prefix, which is dra in most Otomi dialects, developed from an earlier sequence *tana- where the *n became /ɾ/ and the first *a was then lost.A first person present prefix tąną- is attested in Classical Otomi (Lastra, Los Otomies, 40).In summary, the basic syllable is CV, though there are also CCV-type syllables like gwa 'foot' and k 'a 'to be wet'. The maximal syllable is (C)CVC, or (C)CVCC word-internally. The way in which closed syllables appear word-internally en Otomí means that there are no native lexemes with closed syllables word-finally. With one exception there are no words of the type CVC#, the exception being CVɾ(the coda =ɾ is an enclitic).

Only a few types of onset clusters are permissible, and are generally /n+C/ and /h,?+C/, along with /mC/, /kw/, /khw/, /pj/, /pk/, and /ʃC/. This last one appears often in grammatical clitic

Clitic

In morphology and syntax, a clitic is a morpheme that is grammatically independent, but phonologically dependent on another word or phrase. It is pronounced like an affix, but works at the phrase level...

s. The alveolar nasal combines with every consonant. CCC-onsets with /n/ occur. /nhw/, /n?w/, /n?j/, /n?b/ (this last one being the most frequent and is realized as [m?]).

Coda clusters occur on morpheme boundaries, permissible clusters include: /nd/ (hand.gi 'worm'), /nt/, /?b/, /?p/, /?m/, /hn/, /?mb/

Orthography

Caron

A caron or háček , also known as a wedge, inverted circumflex, inverted hat, is a diacritic placed over certain letters to indicate present or historical palatalization, iotation, or postalveolar pronunciation in the orthography of some Baltic, Slavic, Finno-Lappic, and other languages.It looks...

(ǎ). Nasal vowels are marked with a rightward curving hook (ogonek

Ogonek

The ogonek is a diacritic hook placed under the lower right corner of a vowel in the Latin alphabet used in several European and Native American languages.-Use:...

) at the bottom of the vowel letter: į, ę, ą, ų. The letter c denotes [t͡s] and y denotes [j] and palatal sibilant [ʃ] is written with the letter š, and palatal nasal [ɲ] is written ñ. The remaining symbols are from the IPA

International Phonetic Alphabet

The International Phonetic Alphabet "The acronym 'IPA' strictly refers [...] to the 'International Phonetic Association'. But it is now such a common practice to use the acronym also to refer to the alphabet itself that resistance seems pedantic...

with their standard values.

Classical Otomi

Colonial documents in Classical Otomi do not generally capture all the phonological contrasts of the Otomi language. Since the friars who alphabetized the Otomi populations were Spanish speakers, it was difficult for them to perceive correctly any contrasts that were present in Otomi but absent in Spanish, such as nasalisation, tone, the large vowel inventory and aspirated and glottal consonants. Even when they recognized that there were additional phonemic contrasts in Otomi they often had difficulties choosing how to transcribe them and in doing so consistently. No colonial documents include information on tone. The existence of nasalization is noted by Cárceres, but he does not transcribe it. Cárceres used the letter æ for low central unrounded vowel [ʌ] and æ with cedille for the high central unrounded vowel ɨ. He also transcribed glottalized consonants as geminates e.g. ttz for [t͡sʔ]. Cárceres used grave-accented vowels è and ò for [ɛ] and [ɔ]. In the 18th century Neve y Molina used vowels with macronMacron

A macron, from the Greek , meaning "long", is a diacritic placed above a vowel . It was originally used to mark a long or heavy syllable in Greco-Roman metrics, but now marks a long vowel...

ē and ō for those, and invented extra letters (an e with a tail and a hook and an u with a tail) to represent the central vowels.

Practical orthography for modern dialects

OrthographiesOrthography

The orthography of a language specifies a standardized way of using a specific writing system to write the language. Where more than one writing system is used for a language, for example Kurdish, Uyghur, Serbian or Inuktitut, there can be more than one orthography...

used to write modern Otomi have been a focus of controversy among field linguists for many years. Particularly contentious is the issue of whether or not to mark tone, and how, in orthographies to be used by native speakers. Many practical orthographies used by Otomi speakers do not include tone marking. Bartholomew has been a leading advocate for the marking of tone, arguing that because tone is an integrated element of the language's grammatical and lexical systems, the failure to indicate it would lead to ambiguity. Bernard, on the other hand, has argued that native speakers prefer a toneless orthography because they can almost always disambiguate using context, and because they are often unaware of the significance of tone in their language, and consequently have difficulty learning to apply the tone diacritics correctly. For Mezquital Otomi, Bernard accordingly created an orthography in which tone was indicated only when necessary to disambiguate between two words and in which the only symbols used were those available on a standard Spanish language typewriter (employing for example the letter c for [ɔ], v for [ʌ], and the symbol + for [ɨ]).

Practical orthographies used to promote Otomi literacy have been designed and published by the Instituto Lingüístico de Verano

Instituto Lingüístico de Verano (Mexico)