Maze Prison escape

Encyclopedia

The Maze Prison escape took place on 25 September 1983 in County Antrim

, Northern Ireland

. HM Prison Maze

(previously known as Long Kesh) was a maximum security prison considered to be one of the most escape-proof prisons in Europe, and held prisoners convicted of taking part in armed paramilitary campaigns during the Troubles

. In the biggest prison escape

in British

history, 38 Provisional Irish Republican Army

(IRA) prisoners, who had been convicted of offences including murder and causing explosions, escaped from H-Block 7 (H7) of the prison. One prison officer died of a heart attack as a result of the escape and twenty others were injured, including two who were shot with guns that had been smuggled into the prison. The escape was a propaganda coup for the IRA, and a British government minister faced calls to resign. The official inquiry into the escape placed most of the blame onto prison staff, who in turn blamed the escape on political interference in the running of the prison.

and appeared at a press conference in Dublin. On 17 January 1972, seven internees

escaped from the prison ship HMS Maidstone

by swimming to freedom, resulting in them being dubbed the "Magnificent Seven". On 31 October 1973, three leading IRA members, including former Chief of Staff Seamus Twomey

, escaped from Mountjoy Prison

in Dublin when a helicopter landed in the exercise yard of the prison. Irish band The Wolfe Tones wrote a song celebrating the escape called "The Helicopter Song

", which topped the Irish popular music charts. 19 IRA members escaped from Portlaoise Jail on 18 August 1974 after overpowering guards and using gelignite

to blast through gates, and 33 prisoners attempted to escape from Long Kesh on 6 November 1974 after digging a tunnel. IRA member Hugh Coney was shot dead by a sentry, 29 other prisoners were captured within a few yards of the prison, and the remaining three were back in custody within 24 hours. In March 1975, ten prisoners escaped from the courthouse in Newry

while on trial for attempting to escape from Long Kesh. The escapees included Larry Marley, who would later be one of the masterminds behind the 1983 escape. On 10 June 1981, eight IRA members on remand, including Angelo Fusco

, Paul Magee

and Joe Doherty

, escaped from Crumlin Road Jail. The prisoners took prison officers hostage using three handguns that had been smuggled into the prison, took their uniforms and shot their way out of the prison.

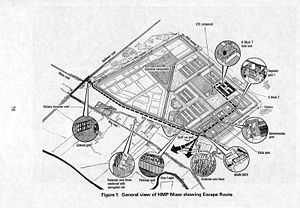

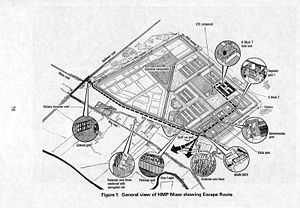

, and all gates on the complex were made of solid steel and electronically operated. Prisoners had been planning the escape for several months. Bobby Storey

and Gerry Kelly

had started working as orderlies in H7, which allowed them to identify weaknesses in the security systems, and six handguns had been smuggled into the prison. Shortly after 2:30 pm on 25 September, prisoners seized control of H7 by simultaneously taking the prison officers hostage at gunpoint in order to prevent them from triggering an alarm. One officer was stabbed with a craft knife, and another was knocked down by a blow to the back of the head. One officer who attempted to prevent the escape was shot in the head by Gerry Kelly, but survived. By 2:50 pm the prisoners were in total control of H7 without an alarm being raised. A dozen prisoners also took uniforms from the officers, and the officers were also forced to hand over their car keys and details of where their cars were, for possible later use during the escape. A rear guard was left behind to watch over hostages and keep the alarm from being raised until they believed the escapees were clear of the prison, when they returned to their cells. At 3:25 pm, a lorry delivering food supplies arrived at the entrance to H7, where Brendan McFarlane

and other prisoners took the occupants hostage at gunpoint and took them inside H7. The lorry driver was told the lorry was being used in the escape, and he was instructed what route to take and how to react if challenged. Bobby Storey told the driver that "This man [Gerry Kelly] is doing 30 years and he will shoot you without hesitation if he has to. He has nothing to lose".

At 3:50 pm the prisoners left H7, and the driver and a prison orderly were taken back to the lorry, and the driver's foot tied to the clutch

. 37 prisoners climbed into the back of the lorry, while Gerry Kelly lay on the floor of the cab with a gun pointed at the driver, who was also told the cab had been booby trap

ped with a hand grenade

. At nearly 4:00 pm the lorry drove towards the main gate of the prison, where the prisoners intended to take over the gatehouse. Ten prisoners dressed in guards' uniforms and armed with guns and chisels dismounted from the lorry and entered the gatehouse, where they took the officers hostage. At 4:05 pm the officers began to resist, and an officer pressed an alarm button. When other staff responded via an intercom, a senior officer said while being held at gunpoint that the alarm had been triggered accidentally. By this time the prisoners were struggling to maintain control in the gatehouse due to the number of hostages. Officers arriving for work were entering the gatehouse from outside the prison, and each was ordered at gunpoint to join the other hostages. Officer James Ferris ran from the gatehouse towards the pedestrian gate attempting to raise the alarm, pursued by Dermot Finucane. Ferris had already been stabbed three times in the chest, and before he could raise the alarm he collapsed.

Finucane continued to the pedestrian gate where he stabbed the officer controlling the gate, and two officers who had just entered the prison. This incident was seen by a soldier on duty in a watch tower, who reported to the Army operations room that he had seen prison officers fighting. The operations room telephoned the prison's Emergency Control Room (ECR), which replied that everything was all right and that an alarm had been accidentally triggered earlier. At 4:12 pm the alarm was raised when an officer in the gatehouse pushed the prisoner holding him hostage out of the room and telephoned the ECR. However, this was not done soon enough to prevent the escape. After several attempts the prisoners had opened the main gate, and were waiting for the prisoners still in the gatehouse to rejoin them in the lorry. At this time two prison officers blocked the exit with their cars, forcing the prisoners to abandon the lorry and make their way to the outer fence which was 25 yards away. Four prisoners attacked one of the officers and hijacked his car, which they drove towards the external gate. They crashed into a car near the gate and abandoned the car. Two escaped through the gate, one was captured exiting the car, and another was captured after being chased by a soldier. At the main gate, a prison officer was shot in the leg while chasing the only two prisoners who had not yet reached the outer fence. The prisoner who fired the shot was captured after being shot and wounded by a soldier in a watch tower, and the other prisoner was captured after falling. The other prisoners escaped over the fence, and by 4:18 pm the main gate was closed and the prison secured, after 35 prisoners had successfully breached the perimeter of the prison. The escape was the biggest in British history, and the biggest in Europe since World War II

Finucane continued to the pedestrian gate where he stabbed the officer controlling the gate, and two officers who had just entered the prison. This incident was seen by a soldier on duty in a watch tower, who reported to the Army operations room that he had seen prison officers fighting. The operations room telephoned the prison's Emergency Control Room (ECR), which replied that everything was all right and that an alarm had been accidentally triggered earlier. At 4:12 pm the alarm was raised when an officer in the gatehouse pushed the prisoner holding him hostage out of the room and telephoned the ECR. However, this was not done soon enough to prevent the escape. After several attempts the prisoners had opened the main gate, and were waiting for the prisoners still in the gatehouse to rejoin them in the lorry. At this time two prison officers blocked the exit with their cars, forcing the prisoners to abandon the lorry and make their way to the outer fence which was 25 yards away. Four prisoners attacked one of the officers and hijacked his car, which they drove towards the external gate. They crashed into a car near the gate and abandoned the car. Two escaped through the gate, one was captured exiting the car, and another was captured after being chased by a soldier. At the main gate, a prison officer was shot in the leg while chasing the only two prisoners who had not yet reached the outer fence. The prisoner who fired the shot was captured after being shot and wounded by a soldier in a watch tower, and the other prisoner was captured after falling. The other prisoners escaped over the fence, and by 4:18 pm the main gate was closed and the prison secured, after 35 prisoners had successfully breached the perimeter of the prison. The escape was the biggest in British history, and the biggest in Europe since World War II

.

Outside the prison the IRA had planned a logistical support operation involving 100 armed members, but due to a miscalculation of five minutes the prisoners found no transport waiting for them and were forced to flee across fields or hijack vehicles. The British Army

and Royal Ulster Constabulary

immediately activated a contingency plan, and by 4:25 pm a cordon of vehicle check points were in place around the prison, and others were later in place in strategic positions across Northern Ireland, resulting in the recapture of one prisoner at 11:00 pm. Twenty prison officers were injured during the escape, thirteen were kicked and beaten, four stabbed, two shot, and another, James Ferris, died after suffering a heart attack during the escape.

Ian Paisley

called on Nicholas Scott

, the Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State

for Northern Ireland, to resign. The British Prime Minister

Margaret Thatcher

made a statement in Ottawa

during a visit to Canada, saying "It is the gravest [breakout] in our present history, and there must be a very deep inquiry". The day after the escape, Secretary of State for Northern Ireland

James Prior announced an inquiry would be headed by Her Majesty's Chief Inspector of Prisons

, James Hennessy. The Hennessy Report was published on 26 January 1984 placing most of the blame for the escape on prison staff, and made a series of recommendations to improve security at the prison. The report also placed blame with the designers of the prison, the Northern Ireland Office

and successive prison governors who had failed to improve security. James Prior announced the prison's governor had resigned, and that there would be no ministerial resignations as a result of the report's findings. Four days after the Hennessy Report was published, then Minister for Prisons Nicholas Scott dismissed allegations from the Prison Governors Association and the Prison Officers Association

that the escape was due to political interference in the running of the prison. On 25 October 1984, nineteen prisoners appeared in court on charges relating to the death of prison officer James Ferris, sixteen of them charged with his murder. A pathologist stated that the stab wounds Ferris suffered would not have killed a healthy man, and the judge acquitted all sixteen as he could not be satisfied that the heart attack was caused by the stabbing.

where two members of the IRA's South Armagh Brigade were in charge of transporting them to safehouses, and they were given the option of either returning to active service in the IRA's armed campaign or a job and new identity in the United States.

Escapee Kieran Fleming

drowned in the Bannagh River near Kesh

in December 1984, while attempting to escape from an ambush by the Special Air Service

(SAS) in which fellow IRA member Antoine Mac Giolla Bhrighde was killed. Gerard McDonnell was captured in Glasgow

in June 1985 along with four other IRA members including Brighton bomber

Patrick Magee, and convicted of conspiring to cause sixteen explosions across England. Séamus McElwaine

was killed by the SAS in Roslea in April 1986, and Gerry Kelly and Brendan McFarlane were returned to prison in December 1986 after being extradited

from Amsterdam

where they had been arrested in January 1986, leaving twelve escapees still on the run. Pádraig McKearney

was killed by the SAS along with seven other members of the IRA's East Tyrone Brigade

in Loughgall

in May 1987, the IRA's biggest single loss of life since the 1920s. In November 1987 Paul Kane and the mastermind of the escape Dermot Finucane, brother of Belfast

solicitor Pat Finucane who was later killed by loyalist

paramilitaries in 1989, were arrested in Granard

, County Longford

on extradition warrants issued by the British authorities. Robert Russell was extradited back to Northern Ireland in August 1988 after being captured in Dublin in 1984, and Paul Kane followed in April 1989. In March 1990 the Supreme Court of Ireland in Dublin blocked the extradition of James Pius Clarke and Dermot Finucane on the grounds they "would be probable targets for ill-treatment by prison staff" if they were returned to prison in Northern Ireland.

Kevin Barry Artt, Pól Brennan, James Smyth and Terrence Kirby, collectively known as the "H-Block 4", were arrested in the United States between 1992 and 1994 and fought lengthy legal battles against extradition. Smyth was extradited back to Northern Ireland in 1996 and returned to prison, before being released in 1998 as part of the Good Friday Agreement. Tony Kelly was arrested in Letterkenny

, County Donegal

in October 1997, and fought successfully against extradition. In 2000 the British government announced that the extradition requests for Brennan, Artt and Kirby were being withdrawn as part of the Good Friday Agreement. The men officially remain fugitives, but in 2003 the Prison Service

said they were not being "actively pursued". Dermot McNally, who had been living in the Republic of Ireland and was tracked down in 1996, and Dermot Finucane received an amnesty in January 2002, allowing them to return to Northern Ireland if they wished to. However Tony McAllister was not granted an amnesty which would have allowed him to return to his home in Ballymurphy

. As of September 2003 two escapees, Gerard Fryers and Séamus Campbell, had not been traced since the escape. Up to 800 republicans held a party at a hotel in Donegal

in September 2003 to celebrate the 20th anniversary of the escape, which was described by Ulster Unionist Party

MP Jeffrey Donaldson

as "insensitive, inappropriate and totally unnecessary".

prisoner Benjamin Redfern, a member of the Ulster Defence Association

, attempted to escape from HM Prison Maze by hiding in the back of a refuse lorry

, but died after being caught in the crushing mechanism. On 7 July 1991 IRA prisoners Nessan Quinlivan

and Pearse McAuley escaped from HM Prison Brixton

, where they were being held on remand. They escaped using a gun that had been smuggled into the prison, wounding a motorist as they fled after escaping the prison. On 9 September 1994 six prisoners including an armed robber, Danny McNamee

and four IRA members including Paul Magee

, escaped from HM Prison Whitemoor

. The prisoners, in possession of two guns that had been smuggled into the prison, scaled the prison walls using knotted sheets. A guard was shot and wounded during the escape, and the prisoners were captured after being chased across fields by guards and the police. In March 1997 a 40 feet (12 m) tunnel was discovered in H7 at HM Prison Maze. The tunnel was fitted with electric lights, and was 80 feet (24 m) from the outside wall having already breached the block's perimeter wall. On 10 December 1997 IRA prisoner Liam Averill, serving a life sentence after being convicted of the murder of two Protestants, escaped from HM Prison Maze dressed as a woman. Averill mingled with a group of prisoners' families attending a Christmas party, and escaped on the coach taking the families out of the prison.

County Antrim

County Antrim is one of six counties that form Northern Ireland, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland. Adjoined to the north-east shore of Lough Neagh, the county covers an area of 2,844 km², with a population of approximately 616,000...

, Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland is one of the four countries of the United Kingdom. Situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, it shares a border with the Republic of Ireland to the south and west...

. HM Prison Maze

Maze (HM Prison)

Her Majesty's Prison Maze was a prison in Northern Ireland that was used to house paramilitary prisoners during the Troubles from mid-1971 to mid-2000....

(previously known as Long Kesh) was a maximum security prison considered to be one of the most escape-proof prisons in Europe, and held prisoners convicted of taking part in armed paramilitary campaigns during the Troubles

The Troubles

The Troubles was a period of ethno-political conflict in Northern Ireland which spilled over at various times into England, the Republic of Ireland, and mainland Europe. The duration of the Troubles is conventionally dated from the late 1960s and considered by many to have ended with the Belfast...

. In the biggest prison escape

Prison escape

A prison escape or prison break is the act of an inmate leaving prison through unofficial or illegal ways. Normally, when this occurs, an effort is made on the part of authorities to recapture them and return them to their original detainers...

in British

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

history, 38 Provisional Irish Republican Army

Provisional Irish Republican Army

The Provisional Irish Republican Army is an Irish republican paramilitary organisation whose aim was to remove Northern Ireland from the United Kingdom and bring about a socialist republic within a united Ireland by force of arms and political persuasion...

(IRA) prisoners, who had been convicted of offences including murder and causing explosions, escaped from H-Block 7 (H7) of the prison. One prison officer died of a heart attack as a result of the escape and twenty others were injured, including two who were shot with guns that had been smuggled into the prison. The escape was a propaganda coup for the IRA, and a British government minister faced calls to resign. The official inquiry into the escape placed most of the blame onto prison staff, who in turn blamed the escape on political interference in the running of the prison.

Previous escapes

During the Troubles, Irish republican prisoners had escaped from custody en masse on several occasions. On 17 November 1971, nine prisoners dubbed the "Crumlin Kangaroos" escaped from Crumlin Road Jail when rope ladders were thrown over the wall. Two prisoners were recaptured, but the remaining seven managed to cross the border into the Republic of IrelandRepublic of Ireland

Ireland , described as the Republic of Ireland , is a sovereign state in Europe occupying approximately five-sixths of the island of the same name. Its capital is Dublin. Ireland, which had a population of 4.58 million in 2011, is a constitutional republic governed as a parliamentary democracy,...

and appeared at a press conference in Dublin. On 17 January 1972, seven internees

Internment

Internment is the imprisonment or confinement of people, commonly in large groups, without trial. The Oxford English Dictionary gives the meaning as: "The action of 'interning'; confinement within the limits of a country or place." Most modern usage is about individuals, and there is a distinction...

escaped from the prison ship HMS Maidstone

HMS Maidstone (1937)

HMS Maidstone was a submarine depot ship of the Royal Navy.-Facilities:She was built to support the increasing numbers of submarines, especially on distant stations, such as the Mediterranean and the Pacific Far East...

by swimming to freedom, resulting in them being dubbed the "Magnificent Seven". On 31 October 1973, three leading IRA members, including former Chief of Staff Seamus Twomey

Seamus Twomey

Seamus Twomey was an Irish republican and twice chief of staff of the Provisional IRA.-Biography:Born in Belfast, Twomey lived at 6 Sevastopol Street in the Falls district...

, escaped from Mountjoy Prison

1973 Mountjoy Prison helicopter escape

The Mountjoy Prison helicopter escape occurred on 31 October 1973 when three Provisional Irish Republican Army volunteers escaped from Mountjoy Prison in Dublin, Ireland, aboard a hijacked Alouette II helicopter, which briefly landed in the prison's exercise yard...

in Dublin when a helicopter landed in the exercise yard of the prison. Irish band The Wolfe Tones wrote a song celebrating the escape called "The Helicopter Song

The Helicopter Song

"The Helicopter Song" is a Number 1 single by the Irish traditional band the Wolfe Tones.-Background:The song tells the story of the 1973 escape of three Provisional Irish Republican Army prisoners from Dublin's Mountjoy Prison...

", which topped the Irish popular music charts. 19 IRA members escaped from Portlaoise Jail on 18 August 1974 after overpowering guards and using gelignite

Gelignite

Gelignite, also known as blasting gelatin or simply jelly, is an explosive material consisting of collodion-cotton dissolved in either nitroglycerine or nitroglycol and mixed with wood pulp and saltpetre .It was invented in 1875 by Alfred Nobel, who had earlier invented dynamite...

to blast through gates, and 33 prisoners attempted to escape from Long Kesh on 6 November 1974 after digging a tunnel. IRA member Hugh Coney was shot dead by a sentry, 29 other prisoners were captured within a few yards of the prison, and the remaining three were back in custody within 24 hours. In March 1975, ten prisoners escaped from the courthouse in Newry

Newry

Newry is a city in Northern Ireland. The River Clanrye, which runs through the city, formed the historic border between County Armagh and County Down. It is from Belfast and from Dublin. Newry had a population of 27,433 at the 2001 Census, while Newry and Mourne Council Area had a population...

while on trial for attempting to escape from Long Kesh. The escapees included Larry Marley, who would later be one of the masterminds behind the 1983 escape. On 10 June 1981, eight IRA members on remand, including Angelo Fusco

Angelo Fusco

Angelo Fusco is a former volunteer in the Belfast Brigade of the Provisional Irish Republican Army who escaped during his 1981 trial for killing a Special Air Service officer in 1980....

, Paul Magee

Paul Magee

Paul "Dingus" Magee is a former volunteer in the Belfast Brigade of the Provisional Irish Republican Army who escaped during his 1981 trial for killing a member of the Special Air Service in 1980...

and Joe Doherty

Joe Doherty

Joe Doherty is a former volunteer in the Belfast Brigade of the Provisional Irish Republican Army who escaped during his 1981 trial for killing a member of the Special Air Service in 1980...

, escaped from Crumlin Road Jail. The prisoners took prison officers hostage using three handguns that had been smuggled into the prison, took their uniforms and shot their way out of the prison.

1983 escape

HM Prison Maze was considered one of the most escape-proof prisons in Europe. In addition to 15 feet (4.6 m) fences, each H-Block was encompassed by an 18 feet (5.5 m) concrete wall topped with barbed wireBarbed wire

Barbed wire, also known as barb wire , is a type of fencing wire constructed with sharp edges or points arranged at intervals along the strand. It is used to construct inexpensive fences and is used atop walls surrounding secured property...

, and all gates on the complex were made of solid steel and electronically operated. Prisoners had been planning the escape for several months. Bobby Storey

Bobby Storey

Robert "Big Bobby" Storey is an Irish republican from Belfast, Northern Ireland.He spent in total 20 years in jail, almost all on remand charges. He also played a key role in the Maze prison escape, which was the biggest prison break in British penal history.-Early life:The family was originally...

and Gerry Kelly

Gerry Kelly

Gerard "Gerry" Kelly is an Irish republican politician and former Provisional Irish Republican Army volunteer who played a leading role in the negotiations that led to the Good Friday Agreement on 10 April 1998...

had started working as orderlies in H7, which allowed them to identify weaknesses in the security systems, and six handguns had been smuggled into the prison. Shortly after 2:30 pm on 25 September, prisoners seized control of H7 by simultaneously taking the prison officers hostage at gunpoint in order to prevent them from triggering an alarm. One officer was stabbed with a craft knife, and another was knocked down by a blow to the back of the head. One officer who attempted to prevent the escape was shot in the head by Gerry Kelly, but survived. By 2:50 pm the prisoners were in total control of H7 without an alarm being raised. A dozen prisoners also took uniforms from the officers, and the officers were also forced to hand over their car keys and details of where their cars were, for possible later use during the escape. A rear guard was left behind to watch over hostages and keep the alarm from being raised until they believed the escapees were clear of the prison, when they returned to their cells. At 3:25 pm, a lorry delivering food supplies arrived at the entrance to H7, where Brendan McFarlane

Brendan McFarlane

Brendan "Bik" McFarlane is an Irish republican activist. Born into a Roman Catholic family, he was brought up in the Ardoyne area of north Belfast, Northern Ireland. At 16, he left Belfast to train as a priest in a north Wales seminary...

and other prisoners took the occupants hostage at gunpoint and took them inside H7. The lorry driver was told the lorry was being used in the escape, and he was instructed what route to take and how to react if challenged. Bobby Storey told the driver that "This man [Gerry Kelly] is doing 30 years and he will shoot you without hesitation if he has to. He has nothing to lose".

At 3:50 pm the prisoners left H7, and the driver and a prison orderly were taken back to the lorry, and the driver's foot tied to the clutch

Clutch

A clutch is a mechanical device which provides for the transmission of power from one component to another...

. 37 prisoners climbed into the back of the lorry, while Gerry Kelly lay on the floor of the cab with a gun pointed at the driver, who was also told the cab had been booby trap

Booby trap

A booby trap is a device designed to harm or surprise a person, unknowingly triggered by the presence or actions of the victim. As the word trap implies, they often have some form of bait designed to lure the victim towards it. However, in other cases the device is placed on busy roads or is...

ped with a hand grenade

Hand grenade

A hand grenade is any small bomb that can be thrown by hand. Hand grenades are classified into three categories, explosive grenades, chemical and gas grenades. Explosive grenades are the most commonly used in modern warfare, and are designed to detonate after impact or after a set amount of time...

. At nearly 4:00 pm the lorry drove towards the main gate of the prison, where the prisoners intended to take over the gatehouse. Ten prisoners dressed in guards' uniforms and armed with guns and chisels dismounted from the lorry and entered the gatehouse, where they took the officers hostage. At 4:05 pm the officers began to resist, and an officer pressed an alarm button. When other staff responded via an intercom, a senior officer said while being held at gunpoint that the alarm had been triggered accidentally. By this time the prisoners were struggling to maintain control in the gatehouse due to the number of hostages. Officers arriving for work were entering the gatehouse from outside the prison, and each was ordered at gunpoint to join the other hostages. Officer James Ferris ran from the gatehouse towards the pedestrian gate attempting to raise the alarm, pursued by Dermot Finucane. Ferris had already been stabbed three times in the chest, and before he could raise the alarm he collapsed.

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

.

Outside the prison the IRA had planned a logistical support operation involving 100 armed members, but due to a miscalculation of five minutes the prisoners found no transport waiting for them and were forced to flee across fields or hijack vehicles. The British Army

British Army

The British Army is the land warfare branch of Her Majesty's Armed Forces in the United Kingdom. It came into being with the unification of the Kingdom of England and Scotland into the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1707. The new British Army incorporated Regiments that had already existed in England...

and Royal Ulster Constabulary

Royal Ulster Constabulary

The Royal Ulster Constabulary was the name of the police force in Northern Ireland from 1922 to 2000. Following the awarding of the George Cross in 2000, it was subsequently known as the Royal Ulster Constabulary GC. It was founded on 1 June 1922 out of the Royal Irish Constabulary...

immediately activated a contingency plan, and by 4:25 pm a cordon of vehicle check points were in place around the prison, and others were later in place in strategic positions across Northern Ireland, resulting in the recapture of one prisoner at 11:00 pm. Twenty prison officers were injured during the escape, thirteen were kicked and beaten, four stabbed, two shot, and another, James Ferris, died after suffering a heart attack during the escape.

Reaction

The escape was a propaganda coup and morale boost for the IRA, with Irish republicans dubbing it the "Great Escape". Leading UnionistUnionism in Ireland

Unionism in Ireland is an ideology that favours the continuation of some form of political union between the islands of Ireland and Great Britain...

Ian Paisley

Ian Paisley

Ian Richard Kyle Paisley, Baron Bannside, PC is a politician and church minister in Northern Ireland. As the leader of the Democratic Unionist Party , he and Sinn Féin's Martin McGuinness were elected First Minister and deputy First Minister respectively on 8 May 2007.In addition to co-founding...

called on Nicholas Scott

Nicholas Scott

The Rt. Hon. Sir Nicholas Paul Scott, PC, JP , was a British Conservative Party politician.Scott was educated at Clapham College and was national chairman of the Young Conservatives in 1963...

, the Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State

Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State

A Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State is the lowest of three tiers of government minister in the government of the United Kingdom, junior to both a Minister of State and a Secretary of State....

for Northern Ireland, to resign. The British Prime Minister

Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

The Prime Minister of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the Head of Her Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom. The Prime Minister and Cabinet are collectively accountable for their policies and actions to the Sovereign, to Parliament, to their political party and...

Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher, was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990...

made a statement in Ottawa

Ottawa

Ottawa is the capital of Canada, the second largest city in the Province of Ontario, and the fourth largest city in the country. The city is located on the south bank of the Ottawa River in the eastern portion of Southern Ontario...

during a visit to Canada, saying "It is the gravest [breakout] in our present history, and there must be a very deep inquiry". The day after the escape, Secretary of State for Northern Ireland

Secretary of State for Northern Ireland

The Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, informally the Northern Ireland Secretary, is the principal secretary of state in the government of the United Kingdom with responsibilities for Northern Ireland. The Secretary of State is a Minister of the Crown who is accountable to the Parliament of...

James Prior announced an inquiry would be headed by Her Majesty's Chief Inspector of Prisons

Her Majesty's Chief Inspector of Prisons

Her Majesty's Chief Inspector of Prisons is the head of HM Inspectorate of Prisons and the senior inspector of prisons, young offender institutions and immigration service detention and removal centres in England and Wales...

, James Hennessy. The Hennessy Report was published on 26 January 1984 placing most of the blame for the escape on prison staff, and made a series of recommendations to improve security at the prison. The report also placed blame with the designers of the prison, the Northern Ireland Office

Northern Ireland Office

The Northern Ireland Office is a United Kingdom government department responsible for Northern Ireland affairs. The NIO is led by the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, and is based in Northern Ireland at Stormont House.-Role:...

and successive prison governors who had failed to improve security. James Prior announced the prison's governor had resigned, and that there would be no ministerial resignations as a result of the report's findings. Four days after the Hennessy Report was published, then Minister for Prisons Nicholas Scott dismissed allegations from the Prison Governors Association and the Prison Officers Association

Prison Officers Association

The POA: The Professional Trades Union for Prison, Correctional and Secure Psychiatric Workers is a trade union in the United Kingdom "for prison, correctional and secure psychiatric workers." It currently has a membership of 33,500...

that the escape was due to political interference in the running of the prison. On 25 October 1984, nineteen prisoners appeared in court on charges relating to the death of prison officer James Ferris, sixteen of them charged with his murder. A pathologist stated that the stab wounds Ferris suffered would not have killed a healthy man, and the judge acquitted all sixteen as he could not be satisfied that the heart attack was caused by the stabbing.

Escapees

Fifteen escapees were captured on the first day, including four who were discovered hiding underwater in a river near the prison using reeds to breathe. Four more escapees were captured over the next two days, including Hugh Corey and Patrick Mclntyre who were captured following a two-hour siege at an isolated farmhouse. Out of the remaining 19 escapees, 18 ended up in the republican stronghold of South ArmaghSouth Armagh

South Armagh can refer to:*The southern part of County Armagh*South Armagh *South Armagh...

where two members of the IRA's South Armagh Brigade were in charge of transporting them to safehouses, and they were given the option of either returning to active service in the IRA's armed campaign or a job and new identity in the United States.

Escapee Kieran Fleming

Kieran Fleming

Kieran or Ciarán Fleming , was a member of the 4th Battalion, Derry Brigade of the Provisional Irish Republican Army from the Waterside area of Derry, Northern Ireland. He died while attempting to escape after a confrontation with British troops in 1984.-Background:Fleming was the youngest son of...

drowned in the Bannagh River near Kesh

Kesh, County Fermanagh

Kesh is a village in County Fermanagh, Northern Ireland. It is on the Kesh River about from Lower Lough Erne. The 2001 Census recorded a population of 972 people....

in December 1984, while attempting to escape from an ambush by the Special Air Service

Special Air Service

Special Air Service or SAS is a corps of the British Army constituted on 31 May 1950. They are part of the United Kingdom Special Forces and have served as a model for the special forces of many other countries all over the world...

(SAS) in which fellow IRA member Antoine Mac Giolla Bhrighde was killed. Gerard McDonnell was captured in Glasgow

Glasgow

Glasgow is the largest city in Scotland and third most populous in the United Kingdom. The city is situated on the River Clyde in the country's west central lowlands...

in June 1985 along with four other IRA members including Brighton bomber

Brighton hotel bombing

The Brighton hotel bombing happened on 12 October 1984 at the Grand Hotel in Brighton, England. The bomb was planted by Provisional Irish Republican Army member Patrick Magee, with the intention of assassinating Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and her cabinet who were staying at the hotel for the...

Patrick Magee, and convicted of conspiring to cause sixteen explosions across England. Séamus McElwaine

Séamus McElwaine

Séamus Turlough McElwaine was a volunteer in the South Fermanagh Brigade of the Provisional Irish Republican Army killed by the Special Air Service in 1986...

was killed by the SAS in Roslea in April 1986, and Gerry Kelly and Brendan McFarlane were returned to prison in December 1986 after being extradited

Extradition

Extradition is the official process whereby one nation or state surrenders a suspected or convicted criminal to another nation or state. Between nation states, extradition is regulated by treaties...

from Amsterdam

Amsterdam

Amsterdam is the largest city and the capital of the Netherlands. The current position of Amsterdam as capital city of the Kingdom of the Netherlands is governed by the constitution of August 24, 1815 and its successors. Amsterdam has a population of 783,364 within city limits, an urban population...

where they had been arrested in January 1986, leaving twelve escapees still on the run. Pádraig McKearney

Pádraig McKearney

Pádraig Oliver McKearney was a Marxist-oriented Provisional Irish Republican Army volunteer. He was killed in a Special Air Service ambush with seven other IRA men at Loughgall, County Armagh in May 1987.-Background:...

was killed by the SAS along with seven other members of the IRA's East Tyrone Brigade

Provisional IRA East Tyrone Brigade

The East Tyrone Brigade of the Provisional Irish Republican Army , also known as the Tyrone/Monaghan Brigade was one of the most active republican paramilitary groups in Northern Ireland during "the Troubles"...

in Loughgall

Loughgall

Loughgall is a small village and townland in County Armagh, Northern Ireland. In the 2001 Census it had a population of 285 people.Loughgall was named after a small nearby loch. The village is at the heart of the apple-growing industry and is surrounded by orchards. Along the village's main street...

in May 1987, the IRA's biggest single loss of life since the 1920s. In November 1987 Paul Kane and the mastermind of the escape Dermot Finucane, brother of Belfast

Belfast

Belfast is the capital of and largest city in Northern Ireland. By population, it is the 14th biggest city in the United Kingdom and second biggest on the island of Ireland . It is the seat of the devolved government and legislative Northern Ireland Assembly...

solicitor Pat Finucane who was later killed by loyalist

Ulster loyalism

Ulster loyalism is an ideology that is opposed to a united Ireland. It can mean either support for upholding Northern Ireland's status as a constituent part of the United Kingdom , support for Northern Ireland independence, or support for loyalist paramilitaries...

paramilitaries in 1989, were arrested in Granard

Granard

Granard is a town in the north of County Longford, Ireland and has a traceable history going back to 236 A.D.. It is situated just south of the boundary between the watersheds of the Shannon and the Erne, at the point where the N55 national secondary road and the R194 regional road...

, County Longford

County Longford

County Longford is a county in Ireland. It is part of the Midlands Region and is also located in the province of Leinster. It is named after the town of Longford.Longford County Council is the local authority for the county...

on extradition warrants issued by the British authorities. Robert Russell was extradited back to Northern Ireland in August 1988 after being captured in Dublin in 1984, and Paul Kane followed in April 1989. In March 1990 the Supreme Court of Ireland in Dublin blocked the extradition of James Pius Clarke and Dermot Finucane on the grounds they "would be probable targets for ill-treatment by prison staff" if they were returned to prison in Northern Ireland.

Kevin Barry Artt, Pól Brennan, James Smyth and Terrence Kirby, collectively known as the "H-Block 4", were arrested in the United States between 1992 and 1994 and fought lengthy legal battles against extradition. Smyth was extradited back to Northern Ireland in 1996 and returned to prison, before being released in 1998 as part of the Good Friday Agreement. Tony Kelly was arrested in Letterkenny

Letterkenny

Letterkenny , with a population of 17,568, is the largest town in County Donegal, part of the Province of Ulster in Ireland. The town is located on the River Swilly...

, County Donegal

County Donegal

County Donegal is a county in Ireland. It is part of the Border Region and is also located in the province of Ulster. It is named after the town of Donegal. Donegal County Council is the local authority for the county...

in October 1997, and fought successfully against extradition. In 2000 the British government announced that the extradition requests for Brennan, Artt and Kirby were being withdrawn as part of the Good Friday Agreement. The men officially remain fugitives, but in 2003 the Prison Service

Her Majesty's Prison Service

Her Majesty's Prison Service is a part of the National Offender Management Service of the Government of the United Kingdom tasked with managing most of the prisons within England and Wales...

said they were not being "actively pursued". Dermot McNally, who had been living in the Republic of Ireland and was tracked down in 1996, and Dermot Finucane received an amnesty in January 2002, allowing them to return to Northern Ireland if they wished to. However Tony McAllister was not granted an amnesty which would have allowed him to return to his home in Ballymurphy

Belfast

Belfast is the capital of and largest city in Northern Ireland. By population, it is the 14th biggest city in the United Kingdom and second biggest on the island of Ireland . It is the seat of the devolved government and legislative Northern Ireland Assembly...

. As of September 2003 two escapees, Gerard Fryers and Séamus Campbell, had not been traced since the escape. Up to 800 republicans held a party at a hotel in Donegal

Donegal

Donegal or Donegal Town is a town in County Donegal, Ireland. Its name, which was historically written in English as Dunnagall or Dunagall, translates from Irish as "stronghold of the foreigners" ....

in September 2003 to celebrate the 20th anniversary of the escape, which was described by Ulster Unionist Party

Ulster Unionist Party

The Ulster Unionist Party – sometimes referred to as the Official Unionist Party or, in a historic sense, simply the Unionist Party – is the more moderate of the two main unionist political parties in Northern Ireland...

MP Jeffrey Donaldson

Jeffrey Donaldson

Jeffrey Mark Donaldson, MP is a Northern Irish politician and Member of Parliament for Lagan Valley belonging to the Democratic Unionist Party...

as "insensitive, inappropriate and totally unnecessary".

Subsequent escape attempts

On 10 August 1984 loyalistUlster loyalism

Ulster loyalism is an ideology that is opposed to a united Ireland. It can mean either support for upholding Northern Ireland's status as a constituent part of the United Kingdom , support for Northern Ireland independence, or support for loyalist paramilitaries...

prisoner Benjamin Redfern, a member of the Ulster Defence Association

Ulster Defence Association

The Ulster Defence Association is the largest although not the deadliest loyalist paramilitary and vigilante group in Northern Ireland. It was formed in September 1971 and undertook a campaign of almost twenty-four years during "The Troubles"...

, attempted to escape from HM Prison Maze by hiding in the back of a refuse lorry

Waste collection vehicle

Garbage truck refers to a truck specially designed to collect small quantities of waste and haul the collected waste to a solid waste treatment facility. Other common names for this type of truck include trash truck and dump truck in the United States, and bin wagon, dustcart, dustbin lorry, bin...

, but died after being caught in the crushing mechanism. On 7 July 1991 IRA prisoners Nessan Quinlivan

Nessan Quinlivan

Nessan Quinlivan , is a former Provisional IRA member who escaped from Brixton Prison in London on 7 July 1991 along with his cellmate Pearse McAuley, while awaiting trial on charges relating to a suspected IRA plot to assassinate a former brewery company chairman, Sir Charles Tidbury.In April...

and Pearse McAuley escaped from HM Prison Brixton

Brixton (HM Prison)

HM Prison Brixton is a local men's prison, located in Brixton area of the London Borough of Lambeth, in inner-South London, England. The prison is operated by Her Majesty's Prison Service.-History:...

, where they were being held on remand. They escaped using a gun that had been smuggled into the prison, wounding a motorist as they fled after escaping the prison. On 9 September 1994 six prisoners including an armed robber, Danny McNamee

Danny McNamee

Gilbert "Danny" McNamee is a former electronic engineer from Crossmaglen, Northern Ireland, who was wrongly convicted in 1987 of conspiracy to cause explosions, including the Provisional Irish Republican Army's Hyde Park bombing in 1982.McNamee was arrested on 16 August 1986 at his home in...

and four IRA members including Paul Magee

Paul Magee

Paul "Dingus" Magee is a former volunteer in the Belfast Brigade of the Provisional Irish Republican Army who escaped during his 1981 trial for killing a member of the Special Air Service in 1980...

, escaped from HM Prison Whitemoor

Whitemoor (HM Prison)

HM Prison Whitemoor is a Category A men's prison, located near the town of March in Cambridgeshire, England. The prison is operated by Her Majesty's Prison Service.-History:...

. The prisoners, in possession of two guns that had been smuggled into the prison, scaled the prison walls using knotted sheets. A guard was shot and wounded during the escape, and the prisoners were captured after being chased across fields by guards and the police. In March 1997 a 40 feet (12 m) tunnel was discovered in H7 at HM Prison Maze. The tunnel was fitted with electric lights, and was 80 feet (24 m) from the outside wall having already breached the block's perimeter wall. On 10 December 1997 IRA prisoner Liam Averill, serving a life sentence after being convicted of the murder of two Protestants, escaped from HM Prison Maze dressed as a woman. Averill mingled with a group of prisoners' families attending a Christmas party, and escaped on the coach taking the families out of the prison.