David L. Payne

Encyclopedia

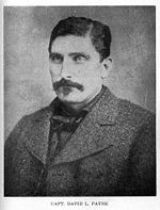

David Lewis Payne was an American soldier

and pioneer. Payne is considered by some to be the "Father of Oklahoma" for his work in opening the state to settlement.

He organized, trained, and led the "Boomer Army" on its forays into the Unassigned Lands

. Payne's excursions into the Unassigned Lands, trips led by others, and lobbying of Congress

by railroad interests eventually convinced the government to open the Unassigned Lands for settlement in 1889, about four years after Payne's death. The formation of Indian Territory

and Oklahoma Territory

followed, and Oklahoma became a state in 1907.

, Indiana

, on a farm near Fairmount

. He grew up working on his father's farm. During winters he attended the local rural school.

In the spring of 1858, Payne and his brother left home intending to join in the Utah War

. Their interest evidently waned by the time they crossed the Missouri River

, as they stopped in Doniphan County

, Kansas

. There, in Burr Oak Township, Payne acquired some land and built a sawmill

. It soon failed and Payne fell to hunting

to support himself. Eventually private parties and then the Federal government

hired him to scout for their various expeditions. These activities led to his exploration of what would later become Oklahoma.

At the opening of the Civil War

At the opening of the Civil War

, Payne enlisted in the 4th Kansas Volunteer Infantry. In April 1862, his regiment

and the 3rd Kansas Infantry and 5th Kansas Infantry were consolidated to form the 10th Kansas Infantry

. He served from August 1861 to August 1864 as a private in Company F. During his service the unit saw action in Kansas, Missouri

, Arkansas

, and the Cherokee Nation

, including the Battle of Prairie Grove

in 1862.

At the end of his three-year service Payne returned to Doniphan County and was elected to the Kansas Legislature

, serving in the 1864 and 1865 sessions.

In March 1865 Payne enlisted for one year in the 15th Kansas Cavalry

as a private assigned to Company H. The unit had been activated in response to a January state legislative resolution which called for the organization of a regiment of veteran volunteer cavalry to protect western Kansas from Indian activity.

In July 1867, Kansas Governor Samuel Johnson Crawford issued a proclamation calling for volunteers to protect Kansans from Indian attacks in the west. The 18th Kansas Cavalry was brought up for four months as a result. Payne enlisted and was mustered in as the captain of Company D. This battalion

replaced the Seventh Cavalry which had been transferred to the Platte River

for the summer. In October 1868, Payne mustered in as a lieutenant in Company H of the 19th Kansas Cavalry, which served in a winter campaign against Indians on the western Great Plains

. During this campaign, Payne served as a scout for General Philip Sheridan

.

In 1870 Payne moved to Sedgwick County

, near Wichita

, and the following year he was again elected to the Kansas Legislature. This led to appointments as Postmaster

at Fort Leavenworth

in 1867 and as Sergeant-at-arms for two terms of the Kansas Senate

. In 1875 and 1879, Payne served as assistant to the Doorkeeper of the United States House of Representatives

.

During the intervals between political engagements and military service, Payne supported himself by hunting, scouting, and guiding wagon train

s.

In 1866, shortly after the Civil War, the Federal government forced many tribes

In 1866, shortly after the Civil War, the Federal government forced many tribes

in the Indian Territory

into making concessions. The government accused the various tribes of abrogating the standing treaties

by joining the Confederacy

. As a result some two million acre

s (8,000 km²) of land in the center of Indian Territory were ceded to the United States and thought by many to be public domain land

.

Elias Boudinot, a Cherokee citizen working as a lobbyist in Washington, D.C.

, published an article about the public land issue in the February 17, 1879 edition of the Chicago Times

. Dr. Morrison Munford of the Kansas City Times

began referring to this tract as the "Unassigned Lands

" or "Oklahoma" and to the people agitating for its settlement as Boomers. Munford is the first person to use the terms "boom" and "boomer" to describe the movement of white settlers into these lands. To prevent settlement of the land, President Rutherford B. Hayes

issued a proclamation in April 1879 forbidding unlawful entry into Indian Territory.

Inspired by Boudinot, Payne began his efforts to enter and settle the public domain lands as allowed by existing law. He returned from his job in Washington and returned to Wichita in 1879. On his first attempt to enter Indian Territory, in April 1880, Payne and his party laid out a town they named "Ewing" on the present-day site of Oklahoma City

. The Fourth Cavalry arrested them, took them to Fort Reno

, then escorted them back to Kansas. Payne was furious, as public law

(specifically the Posse Comitatus Act

) prohibited the military from interfering in civil matters. Payne and his party were freed, which effectively denied them access to federal and state courts.

Anxious to prove his case in court, Payne and a larger group returned to Ewing in July 1879. The Army again arrested the party, escorted them back to Kansas, and freed them. This time, however, Payne was charged under the Indian Intercourse Act

and brought to trial in Fort Smith, Arkansas

in March 1881. Judge Isaac Parker

ruled against Payne and fined him the maximum amount of US$1,000, but since Payne had no money and no property, the fine could not be collected. The ruling settled nothing about the public lands, however, and Payne continued his activities unabated. He organized and led several more expeditions into the territory, even forming a newspaper called the Oklahoma War Chief, the first in the Cherokee Outlet

, which he published in several sites along the Kansas-Indian Territory border.

During one of his last ventures, Payne insisted on a public trial

, so he and his group were hauled the group several hundred miles to Fort Smith. The trip began at Fort Reno and proceed to Fort Sill

, Henrietta, Texas

, Texarkana, Arkansas

, Little Rock, Arkansas

and then finally to Fort Smith. During another trip in July 1884, the army seized his Oklahoma War Chief press, burned his buildings, and took Payne and his group through the Cherokee Nation

after their arrest. The party was paraded through the streets of Tahlequah

, past the Indian people who hated him for his attempts to seize part of their lands.

Public sentiment grew so great over his mistreatment at the hands of the military that the government finally granted his trial. Payne was turned over to the United States District Court for the District of Kansas

at Topeka

. In the fall term, Judge Cassius G. Foster quashed the indictments and ruled that settling on the Unassigned Lands was not a criminal offense. Boomers celebrated, but the government refused to accept the decision.

Between expeditions, Payne often spoke to crowds of admirers and recruited more Boomers. The day after such an address in Wellington, Kansas

on November 27, 1884, Payne collapsed and died of heart failure. His funeral filled the Methodist Episcopal Church

in Wellington and thousands filed past his grave.

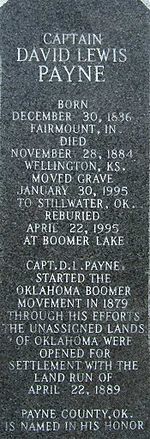

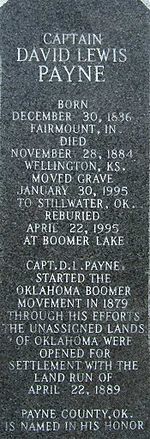

Payne's family moved his remains to Oklahoma in 1995. On April 22, 1996, a monument was dedicated at his final resting place in Stillwater, Oklahoma

. Payne County

, of which Stillwater is the county seat

, which is named in his honor.

William L. Couch

succeeded Payne as leader of the Boomer

movement.

Soldier

A soldier is a member of the land component of national armed forces; whereas a soldier hired for service in a foreign army would be termed a mercenary...

and pioneer. Payne is considered by some to be the "Father of Oklahoma" for his work in opening the state to settlement.

He organized, trained, and led the "Boomer Army" on its forays into the Unassigned Lands

Unassigned Lands

Unassigned Lands, or Oklahoma, were in the center of the lands ceded to the United States by the Creek and Seminole Indians following the Civil War and on which no other tribes had been settled...

. Payne's excursions into the Unassigned Lands, trips led by others, and lobbying of Congress

United States Congress

The United States Congress is the bicameral legislature of the federal government of the United States, consisting of the Senate and the House of Representatives. The Congress meets in the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C....

by railroad interests eventually convinced the government to open the Unassigned Lands for settlement in 1889, about four years after Payne's death. The formation of Indian Territory

Indian Territory

The Indian Territory, also known as the Indian Territories and the Indian Country, was land set aside within the United States for the settlement of American Indians...

and Oklahoma Territory

Oklahoma Territory

The Territory of Oklahoma was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from May 2, 1890, until November 16, 1907, when it was joined with the Indian Territory under a new constitution and admitted to the Union as the State of Oklahoma.-Organization:Oklahoma Territory's...

followed, and Oklahoma became a state in 1907.

Early life

Payne was born in 1836 in Grant CountyGrant County, Indiana

Grant County is a county located in the U.S. state of Indiana. As of the 2010 census, the population was 70,061. The county seat is Marion. Important paleontological discoveries dating from the Pliocene epoch have been made at Pipe Creek Sinkhole in Grant County.-Geography:According to the 2010...

, Indiana

Indiana

Indiana is a US state, admitted to the United States as the 19th on December 11, 1816. It is located in the Midwestern United States and Great Lakes Region. With 6,483,802 residents, the state is ranked 15th in population and 16th in population density. Indiana is ranked 38th in land area and is...

, on a farm near Fairmount

Fairmount, Indiana

Fairmount is a town in Fairmount Township, Grant County in the east central part of the U.S. state of Indiana. The population was 2,992 at the 2000 census. It is ninety kilometers northeast of Indianapolis...

. He grew up working on his father's farm. During winters he attended the local rural school.

In the spring of 1858, Payne and his brother left home intending to join in the Utah War

Utah War

The Utah War, also known as the Utah Expedition, Buchanan's Blunder, the Mormon War, or the Mormon Rebellion was an armed confrontation between LDS settlers in the Utah Territory and the armed forces of the United States government. The confrontation lasted from May 1857 until July 1858...

. Their interest evidently waned by the time they crossed the Missouri River

Missouri River

The Missouri River flows through the central United States, and is a tributary of the Mississippi River. It is the longest river in North America and drains the third largest area, though only the thirteenth largest by discharge. The Missouri's watershed encompasses most of the American Great...

, as they stopped in Doniphan County

Doniphan County, Kansas

Doniphan County is a county located in Northeast Kansas, in the Central United States. As of the 2010 census, the county population was 7,945. Its county seat is Troy and its most populous city is Wathena. The county along with Buchanan, Andrew, and DeKalb counties in Missouri is included in...

, Kansas

Kansas

Kansas is a US state located in the Midwestern United States. It is named after the Kansas River which flows through it, which in turn was named after the Kansa Native American tribe, which inhabited the area. The tribe's name is often said to mean "people of the wind" or "people of the south...

. There, in Burr Oak Township, Payne acquired some land and built a sawmill

Sawmill

A sawmill is a facility where logs are cut into boards.-Sawmill process:A sawmill's basic operation is much like those of hundreds of years ago; a log enters on one end and dimensional lumber exits on the other end....

. It soon failed and Payne fell to hunting

Hunting

Hunting is the practice of pursuing any living thing, usually wildlife, for food, recreation, or trade. In present-day use, the term refers to lawful hunting, as distinguished from poaching, which is the killing, trapping or capture of the hunted species contrary to applicable law...

to support himself. Eventually private parties and then the Federal government

Federal government of the United States

The federal government of the United States is the national government of the constitutional republic of fifty states that is the United States of America. The federal government comprises three distinct branches of government: a legislative, an executive and a judiciary. These branches and...

hired him to scout for their various expeditions. These activities led to his exploration of what would later become Oklahoma.

Soldier and politician

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

, Payne enlisted in the 4th Kansas Volunteer Infantry. In April 1862, his regiment

Regiment

A regiment is a major tactical military unit, composed of variable numbers of batteries, squadrons or battalions, commanded by a colonel or lieutenant colonel...

and the 3rd Kansas Infantry and 5th Kansas Infantry were consolidated to form the 10th Kansas Infantry

10th Regiment Kansas Volunteer Infantry

The 10th Kansas Volunteer Infantry Regiment was an infantry regiment that served in the Union Army during the American Civil War.-Service:The 10th Kansas Infantry was organized at Paola, Kansas by consolidating the 3rd Kansas Infantry and 4th Kansas Infantry, which had recruits, but were never...

. He served from August 1861 to August 1864 as a private in Company F. During his service the unit saw action in Kansas, Missouri

Missouri

Missouri is a US state located in the Midwestern United States, bordered by Iowa, Illinois, Kentucky, Tennessee, Arkansas, Oklahoma, Kansas and Nebraska. With a 2010 population of 5,988,927, Missouri is the 18th most populous state in the nation and the fifth most populous in the Midwest. It...

, Arkansas

Arkansas

Arkansas is a state located in the southern region of the United States. Its name is an Algonquian name of the Quapaw Indians. Arkansas shares borders with six states , and its eastern border is largely defined by the Mississippi River...

, and the Cherokee Nation

Cherokee Nation

The Cherokee Nation is the largest of three Cherokee federally recognized tribes in the United States. It was established in the 20th century, and includes people descended from members of the old Cherokee Nation who relocated voluntarily from the Southeast to Indian Territory and Cherokees who...

, including the Battle of Prairie Grove

Battle of Prairie Grove

The Battle of Prairie Grove was a battle of the American Civil War fought on 7 December 1862, that resulted in a tactical stalemate but essentially secured northwest Arkansas for the Union.-Strategic situation: Union:...

in 1862.

At the end of his three-year service Payne returned to Doniphan County and was elected to the Kansas Legislature

Kansas Legislature

The Kansas Legislature is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Kansas. It is a bicameral assembly, composed of the lower Kansas House of Representatives, composed of 125 Representatives, and the upper Kansas Senate, with 40 Senators...

, serving in the 1864 and 1865 sessions.

In March 1865 Payne enlisted for one year in the 15th Kansas Cavalry

15th Regiment Kansas Volunteer Cavalry

The 15th Kansas Volunteer Cavalry Regiment was a cavalry regiment that served in the Union Army during the American Civil War.-Service:The 15th Kansas Cavalry was organized at Leavenworth, Kansas on October 17, 1863. It mustered in for three years under the command of Colonel Charles R...

as a private assigned to Company H. The unit had been activated in response to a January state legislative resolution which called for the organization of a regiment of veteran volunteer cavalry to protect western Kansas from Indian activity.

In July 1867, Kansas Governor Samuel Johnson Crawford issued a proclamation calling for volunteers to protect Kansans from Indian attacks in the west. The 18th Kansas Cavalry was brought up for four months as a result. Payne enlisted and was mustered in as the captain of Company D. This battalion

Battalion

A battalion is a military unit of around 300–1,200 soldiers usually consisting of between two and seven companies and typically commanded by either a Lieutenant Colonel or a Colonel...

replaced the Seventh Cavalry which had been transferred to the Platte River

Platte River

The Platte River is a major river in the state of Nebraska and is about long. Measured to its farthest source via its tributary the North Platte River, it flows for over . The Platte River is a tributary of the Missouri River, which in turn is a tributary of the Mississippi River which flows to...

for the summer. In October 1868, Payne mustered in as a lieutenant in Company H of the 19th Kansas Cavalry, which served in a winter campaign against Indians on the western Great Plains

Great Plains

The Great Plains are a broad expanse of flat land, much of it covered in prairie, steppe and grassland, which lies west of the Mississippi River and east of the Rocky Mountains in the United States and Canada. This area covers parts of the U.S...

. During this campaign, Payne served as a scout for General Philip Sheridan

Philip Sheridan

Philip Henry Sheridan was a career United States Army officer and a Union general in the American Civil War. His career was noted for his rapid rise to major general and his close association with Lt. Gen. Ulysses S...

.

In 1870 Payne moved to Sedgwick County

Sedgwick County, Kansas

Sedgwick County is a county located in the U.S. state of Kansas. The county's population was 498,365 for the 2010 census. The largest city and county seat is Wichita. The county was named after General John Sedgwick...

, near Wichita

Wichita, Kansas

Wichita is the largest city in the U.S. state of Kansas.As of the 2010 census, the city population was 382,368. Located in south-central Kansas on the Arkansas River, Wichita is the county seat of Sedgwick County and the principal city of the Wichita metropolitan area...

, and the following year he was again elected to the Kansas Legislature. This led to appointments as Postmaster

Postmaster

A postmaster is the head of an individual post office. Postmistress is not used anymore in the United States, as the "master" component of the word refers to a person of authority and has no gender quality...

at Fort Leavenworth

Fort Leavenworth

Fort Leavenworth is a United States Army facility located in Leavenworth County, Kansas, immediately north of the city of Leavenworth in the upper northeast portion of the state. It is the oldest active United States Army post west of Washington, D.C. and has been in operation for over 180 years...

in 1867 and as Sergeant-at-arms for two terms of the Kansas Senate

Kansas Senate

The Kansas Senate is the upper house of the Kansas Legislature, the state legislature of the U.S. State of Kansas. It is composed of 40 Senators representing an equal amount of districts, each with a population of at least 60,000 inhabitants. Members of the Senate are elected to a four year term....

. In 1875 and 1879, Payne served as assistant to the Doorkeeper of the United States House of Representatives

Doorkeeper of the United States House of Representatives

An appointed officer of the United States House of Representatives from 1789 to 1995, the Doorkeeper of the United States House of Representatives was chosen by a resolution at the opening of each United States Congress. The Office of the Doorkeeper was based on precedent from the Continental...

.

During the intervals between political engagements and military service, Payne supported himself by hunting, scouting, and guiding wagon train

Wagon train

A wagon train is a group of wagons traveling together. In the American West, individuals traveling across the plains in covered wagons banded together for mutual assistance, as is reflected in numerous films and television programs about the region, such as Audie Murphy's Tumbleweed and Ward Bond...

s.

Boomer

Native Americans in the United States

Native Americans in the United States are the indigenous peoples in North America within the boundaries of the present-day continental United States, parts of Alaska, and the island state of Hawaii. They are composed of numerous, distinct tribes, states, and ethnic groups, many of which survive as...

in the Indian Territory

Indian Territory

The Indian Territory, also known as the Indian Territories and the Indian Country, was land set aside within the United States for the settlement of American Indians...

into making concessions. The government accused the various tribes of abrogating the standing treaties

Treaty

A treaty is an express agreement under international law entered into by actors in international law, namely sovereign states and international organizations. A treaty may also be known as an agreement, protocol, covenant, convention or exchange of letters, among other terms...

by joining the Confederacy

Stand Watie

Stand Watie , also known as Standhope Uwatie, Degataga , meaning “stand firm”), and Isaac S. Watie, was a leader of the Cherokee Nation and a brigadier general of the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War...

. As a result some two million acre

Acre

The acre is a unit of area in a number of different systems, including the imperial and U.S. customary systems. The most commonly used acres today are the international acre and, in the United States, the survey acre. The most common use of the acre is to measure tracts of land.The acre is related...

s (8,000 km²) of land in the center of Indian Territory were ceded to the United States and thought by many to be public domain land

Public domain (land)

Public domain is a term used to describe lands that were not under private or state ownership during the 18th and 19th centuries in the United States, as the country was expanding. These lands were obtained from the 13 original colonies, from Native American tribes, or from purchase from other...

.

Elias Boudinot, a Cherokee citizen working as a lobbyist in Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly referred to as Washington, "the District", or simply D.C., is the capital of the United States. On July 16, 1790, the United States Congress approved the creation of a permanent national capital as permitted by the U.S. Constitution....

, published an article about the public land issue in the February 17, 1879 edition of the Chicago Times

Chicago Times

The Chicago Times was a newspaper in Chicago from 1854 to 1895 when it merged with the Chicago Herald.The Times was founded in 1854, by James W. Sheahan, with the backing of Stephen Douglas, and was identified as a pro-slavery newspaper. In 1861, after the paper was purchased by Wilbur F...

. Dr. Morrison Munford of the Kansas City Times

Kansas City Times

The Kansas City Times was a morning newspaper in Kansas City, Missouri, that was published from 1867 to 1990.The morning Kansas City Times, under ownership of afternoon The Kansas City Star, won two Pulitzer Prizes and was actually bigger than its parent when its name was changed to the...

began referring to this tract as the "Unassigned Lands

Unassigned Lands

Unassigned Lands, or Oklahoma, were in the center of the lands ceded to the United States by the Creek and Seminole Indians following the Civil War and on which no other tribes had been settled...

" or "Oklahoma" and to the people agitating for its settlement as Boomers. Munford is the first person to use the terms "boom" and "boomer" to describe the movement of white settlers into these lands. To prevent settlement of the land, President Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes was the 19th President of the United States . As president, he oversaw the end of Reconstruction and the United States' entry into the Second Industrial Revolution...

issued a proclamation in April 1879 forbidding unlawful entry into Indian Territory.

Inspired by Boudinot, Payne began his efforts to enter and settle the public domain lands as allowed by existing law. He returned from his job in Washington and returned to Wichita in 1879. On his first attempt to enter Indian Territory, in April 1880, Payne and his party laid out a town they named "Ewing" on the present-day site of Oklahoma City

Oklahoma city

Oklahoma City is the capital and largest city of the U.S. state of Oklahoma.Oklahoma City may also refer to:*Oklahoma City metropolitan area*Downtown Oklahoma City*Uptown Oklahoma City*Oklahoma City bombing*Oklahoma City National Memorial...

. The Fourth Cavalry arrested them, took them to Fort Reno

Fort Reno (Oklahoma)

Fort Reno was established as a permanent post in July 1875, near the Darlington Indian Agency on the old Cheyenne-Arapaho reservation in Indian Territory, in present-day central Oklahoma. Named for General Jesse L. Reno, who died at the Battle of South Mountain, it supported the U.S...

, then escorted them back to Kansas. Payne was furious, as public law

Public law

Public law is a theory of law governing the relationship between individuals and the state. Under this theory, constitutional law, administrative law and criminal law are sub-divisions of public law...

(specifically the Posse Comitatus Act

Posse Comitatus Act

The Posse Comitatus Act is an often misunderstood and misquoted United States federal law passed on June 18, 1878, after the end of Reconstruction. Its intent was to limit the powers of local governments and law enforcement agencies from using federal military personnel to enforce the laws of...

) prohibited the military from interfering in civil matters. Payne and his party were freed, which effectively denied them access to federal and state courts.

Anxious to prove his case in court, Payne and a larger group returned to Ewing in July 1879. The Army again arrested the party, escorted them back to Kansas, and freed them. This time, however, Payne was charged under the Indian Intercourse Act

Indian Intercourse Act

The Nonintercourse Act is the collective name given to six statutes passed by the United States Congress in 1790, 1793, 1796, 1799, 1802, and 1834. The Act regulates commerce between Native Americans and non-Indians...

and brought to trial in Fort Smith, Arkansas

Fort Smith, Arkansas

Fort Smith is the second-largest city in Arkansas and one of the two county seats of Sebastian County. With a population of 86,209 in 2010, it is the principal city of the Fort Smith, Arkansas-Oklahoma Metropolitan Statistical Area, a region of 298,592 residents which encompasses the Arkansas...

in March 1881. Judge Isaac Parker

Isaac Parker

Isaac Charles Parker served as a U.S. District Judge presiding over the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Arkansas for 21 years and also one-time politician. He served in that capacity during the most dangerous time for law enforcement during the western expansion...

ruled against Payne and fined him the maximum amount of US$1,000, but since Payne had no money and no property, the fine could not be collected. The ruling settled nothing about the public lands, however, and Payne continued his activities unabated. He organized and led several more expeditions into the territory, even forming a newspaper called the Oklahoma War Chief, the first in the Cherokee Outlet

Cherokee Outlet

The Cherokee Outlet, often mistakenly referred to as the Cherokee Strip, was located in what is now the state of Oklahoma, in the United States. It was a sixty-mile wide strip of land south of the Oklahoma-Kansas border between the 96th and 100th meridians. It was about 225 miles long and in 1891...

, which he published in several sites along the Kansas-Indian Territory border.

During one of his last ventures, Payne insisted on a public trial

Public trial

Public trial or open trial is a trial open to public, as opposed to the secret trial. The term should not be confused with show trial.-United States:...

, so he and his group were hauled the group several hundred miles to Fort Smith. The trip began at Fort Reno and proceed to Fort Sill

Fort Sill

Fort Sill is a United States Army post near Lawton, Oklahoma, about 85 miles southwest of Oklahoma City.Today, Fort Sill remains the only active Army installation of all the forts on the South Plains built during the Indian Wars...

, Henrietta, Texas

Henrietta, Texas

Henrietta is a city in and the county seat of Clay County, Texas, United States. It is part of the Wichita Falls, Texas Metropolitan Statistical Area. The population was 3,264 at the 2000 census.-History:...

, Texarkana, Arkansas

Texarkana, Arkansas

As of the census of 2000, there were 26,448 people, 10,384 households, and 7,040 families residing in the city. The population density was 830.5 people per square mile . There were 11,721 housing units at an average density of 368.1 per square mile...

, Little Rock, Arkansas

Little Rock, Arkansas

Little Rock is the capital and the largest city of the U.S. state of Arkansas. The Metropolitan Statistical Area had a population of 699,757 people in the 2010 census...

and then finally to Fort Smith. During another trip in July 1884, the army seized his Oklahoma War Chief press, burned his buildings, and took Payne and his group through the Cherokee Nation

Cherokee Nation

The Cherokee Nation is the largest of three Cherokee federally recognized tribes in the United States. It was established in the 20th century, and includes people descended from members of the old Cherokee Nation who relocated voluntarily from the Southeast to Indian Territory and Cherokees who...

after their arrest. The party was paraded through the streets of Tahlequah

Tahlequah, Oklahoma

Tahlequah is a city in Cherokee County, Oklahoma, United States located at the foothills of the Ozark Mountains. It was founded as a capital of the original Cherokee Nation in 1838 to welcome those Cherokee forced west on the Trail of Tears. The city's population was 15,753 at the 2010 census. It...

, past the Indian people who hated him for his attempts to seize part of their lands.

Public sentiment grew so great over his mistreatment at the hands of the military that the government finally granted his trial. Payne was turned over to the United States District Court for the District of Kansas

United States District Court for the District of Kansas

The United States District Court for the District of Kansas is the federal district court whose jurisdiction is the state of Kansas. The Court operates out of the Robert J. Dole United States Courthouse in Kansas City, the Frank Carlson Federal Building in Topeka, and the United States Courthouse...

at Topeka

Topeka, Kansas

Topeka |Kansa]]: Tó Pee Kuh) is the capital city of the U.S. state of Kansas and the county seat of Shawnee County. It is situated along the Kansas River in the central part of Shawnee County, located in northeast Kansas, in the Central United States. As of the 2010 census, the city population was...

. In the fall term, Judge Cassius G. Foster quashed the indictments and ruled that settling on the Unassigned Lands was not a criminal offense. Boomers celebrated, but the government refused to accept the decision.

Between expeditions, Payne often spoke to crowds of admirers and recruited more Boomers. The day after such an address in Wellington, Kansas

Wellington, Kansas

Wellington is a city in and the county seat of Sumner County, Kansas, United States. As of the 2010 census, the city population was 8,172.-19th century:...

on November 27, 1884, Payne collapsed and died of heart failure. His funeral filled the Methodist Episcopal Church

Methodist Episcopal Church

The Methodist Episcopal Church, sometimes referred to as the M.E. Church, was a development of the first expression of Methodism in the United States. It officially began at the Baltimore Christmas Conference in 1784, with Francis Asbury and Thomas Coke as the first bishops. Through a series of...

in Wellington and thousands filed past his grave.

Payne's family moved his remains to Oklahoma in 1995. On April 22, 1996, a monument was dedicated at his final resting place in Stillwater, Oklahoma

Stillwater, Oklahoma

Stillwater is a city in north-central Oklahoma at the intersection of U.S. 177 and State Highway 51. It is the county seat of Payne County, Oklahoma, United States. As of the 2010 census, the city population was 45,688. Stillwater is the principal city of the Stillwater Micropolitan Statistical...

. Payne County

Payne County, Oklahoma

Payne County is a county in the U.S. state of Oklahoma. The population as of 2010 was 77,350. Its county seat is Stillwater, and the county is named for Capt. David L. Payne...

, of which Stillwater is the county seat

County seat

A county seat is an administrative center, or seat of government, for a county or civil parish. The term is primarily used in the United States....

, which is named in his honor.

William L. Couch

William Couch

William Lewis Couch was a leader of the Boomer Movement and the first mayor of Oklahoma City, Oklahoma.He was born in North Carolina, later moving to Kansas as a farmer. He joined the Boomer Movement in 1880 and became the sole leader of the movement after David L. Payne's death on November 28,...

succeeded Payne as leader of the Boomer

Boomers (Oklahoma settlers)

Boomers is the name given to settlers in the midwest of the United States who attempted to enter the Unassigned Lands in what is now the state of Oklahoma in 1879, prior to President Grover Cleveland officially proclaiming them open to settlement on March 2, 1889 with the Indian Appropriations Act...

movement.

External links

- Art of the Oklahoma State Capitol - David L. Payne bust

- http://www.visitstillwater.org/CustomContentRetrieve.aspx?ID=262582 David L Payne Memorial Monument